Abstract

We estimated the reproducibility of tandem mass fragmentation spectra for the widely-used collision-induced dissociation (CID) instruments. Using the Pearson correlation coefficient as a measure of spectral similarity, we found that the within-experiment reproducibility of fragment ion intensities is very high (about 0.85). However, across different experiments and instrument types/setups, the correlation decreases by more than 15% (to about 0.70). We further investigated the accuracy of current predictors of peptide fragmentation spectra and found that they are more accurate than the ad-hoc models generally used by search engines (e.g. SEQUEST) and, surprisingly, approaching the empirical upper limit set by the average across-experiment spectral reproducibility (especially for charge +1 and charge +2 precursor ions). These results provide evidence that, in terms of accuracy of modeling, predicted peptide fragmentation spectra provide a viable alternative to spectral libraries for peptide identification, with a higher coverage of peptides and lower storage requirements. Furthermore, using five data sets of proteome digests by two different proteases, we find that PeptideART (a data-driven machine learning approach) is generally more accurate than MassAnalyzer (an approach based on a kinetic model for peptide fragmentation) in predicting fragmentation spectra, but that both models are significantly more accurate than the ad-hoc models. Availability: PeptideART is freely available at www.informatics.indiana.edu/predrag.

Introduction

Tandem mass spectrum interpretation has been challenging from the early days of shotgun proteomics.1 Original tools such as SEQUEST2,3 and MASCOT,4 which adopted a database search strategy that matches experimental tandem mass (MS/MS) spectra to the theoretical spectra of peptides in a protein database, are still widely used. However, even with the best tools available, a large fraction of MS/MS spectra are not identified.5

To increase the fraction of identified spectra, the recent development of database search tools has largely focused on two strategies. The first strategy attempts to incorporate additional experimental information into the peptide identification, e.g. to compare the reversed-phase retention time associated with the MS/MS spectra with the predicted retention time of the peptides,6 to use accurate mass and time analysis in spectral matching,7 to generate the consensus spectrum for multiple pre-clustered MS/MS spectra of the same peptide for database searching,8 and to combine results from multiple MS/MS search engines.9 The second strategy attempts to improve the scoring scheme for the spectral matching, e.g. to assess not only the number of matched peaks but also their intensities10,11 or to design matching scores based on the amino acid-specific biases in peptide fragmentation.12–15 A recent review by Barton and Whittaker provides an excellent discussion of the second group of algorithms as well as the physicochemical factors that are known to affect peptide fragmentation.16

For the peptides that fragment well, the database search or, in particular, the peptide-spectrum matching (PSM) problem becomes straightforward if the MS/MS spectra are available for all peptide sequences in the database, since it has been observed that the spectra were reproducible and distinct from one peptide to another. As a result, a new approach to peptide identification, based on the experience with small molecule identification,17,18 was proposed. It matches experimental MS/MS spectra to the previously identified peptide spectra stored in peptide libraries.19–23 It was shown that the peptide library approach can identify more spectra than the conventional database searching methods.21,22 However, the estimates of the amount of increase in sensitivity and the number of identified peptides are still preliminary. In addition, the relative importance of searching smaller databases vs. the use of peak intensities has not been quantified. In any case, the spectral library approach is practical only when the spectra have been characterized for all peptides in the sample (or at least all detectable24 or proteotypic25 peptides) and can be applied for the well-studied samples (e.g. blood samples) or relatively simple model organisms (e.g. yeast). As a result, hybrid approaches and workflows that combine conventional database searches with spectral library searches, have emerged.26,27

The spectral library approach can be eliminated if the relative intensities, not only the occurrences of the fragment ions in the experimental spectrum can be accurately predicted from a peptide sequence alone. Indeed, several computational methods have been developed using either physicochemical models of peptide fragmentation28,29 or machine learning.30–33 From limited benchmarking tests, these predictors, as well as those predicting the order of peak intensities,34 have shown good accuracy and can potentially be used to assist peptide identification.

Peptide fragmentation is inherently stochastic. Combined with other random events such as fluctuations of the ionization source and ion detection, it can result in differences between fragment spectra of the same peptide even in the same experiment. When different instruments, experimental setups or PSM algorithms are applied, the spectra matched to the same peptide can be significantly different. For example, Venable and Yates studied the variance of PSM scores and found that the distribution of scores depends not only on peptide sequence but also on its quantity.35 Thus, methods relying on grouping of experimental spectra have been shown to improve peptide identifications.8,36,37 Similarly, spectrum averaging over different experimental setups plays an important role in building spectral libraries.22 As a result, it is necessary to further understand and quantify the variability of experimental fragmentation spectra corresponding to the same peptide. In light of the advent of more sophisticated algorithms for predicting fragmentation spectra, this can also help in determining the usefulness of such computational tools because their accuracy cannot be larger than the experimental reproducibility of the fragmentation spectra.

In this paper, we report a systematic assessment of the reproducibility of peptide fragmentation spectra as well as the accuracy of the current peptide MS/MS spectrum predictors for the most commonly used collision-induced dissociation (CID) instruments. We find that an average correlation between two MS/MS spectra repeatedly identified as the same peptide in the same experiment is very high over all precursor ion charge states. However, across different experiments, instrument types or experimental setups, we find that this correlation decreases by 15% or even more (see Results), but is still substantially higher than the correlation of the ad-hoc models used in peptide search engines. We also computed the correlation coefficients between the experimental and predicted spectra for two predictors: MassAnalyzer, which uses a kinetic model of peptide fragmentation,28,29 and PeptideART, which adopts a data-driven approach.31 Both computational tools achieve considerable performance improvement over the ad-hoc models, although correlation coefficients are still somewhat lower, depending on the precursor ion charge state, than the across-experiment spectral reproducibility. Overall, this work supports the use of spectral libraries to most accurately model peptide fragmentation spectra. It also provides evidence that computational models such as MassAnalyzer and PeptideART are viable alternatives to spectral libraries in terms of accuracy, but offering several advantages with respect to proteome coverage or storage requirements.

Results

Reproducibility of CID-MS/MS spectra of identical peptides

In the first experiment we estimated the empirical upper limit for the reproducibility of experimental MS/MS spectra within and across proteomics experiments. For the within-experiment analysis we used a subset of identified peptides with spectral counts greater than 1 from Human, Mouse and Yeast data sets (see Materials and Methods). For each identified unique peptide, we calculated the average Pearson correlation coefficient over all pairs of spectra. Finally, the average correlation coefficient over all unique peptides is reported.

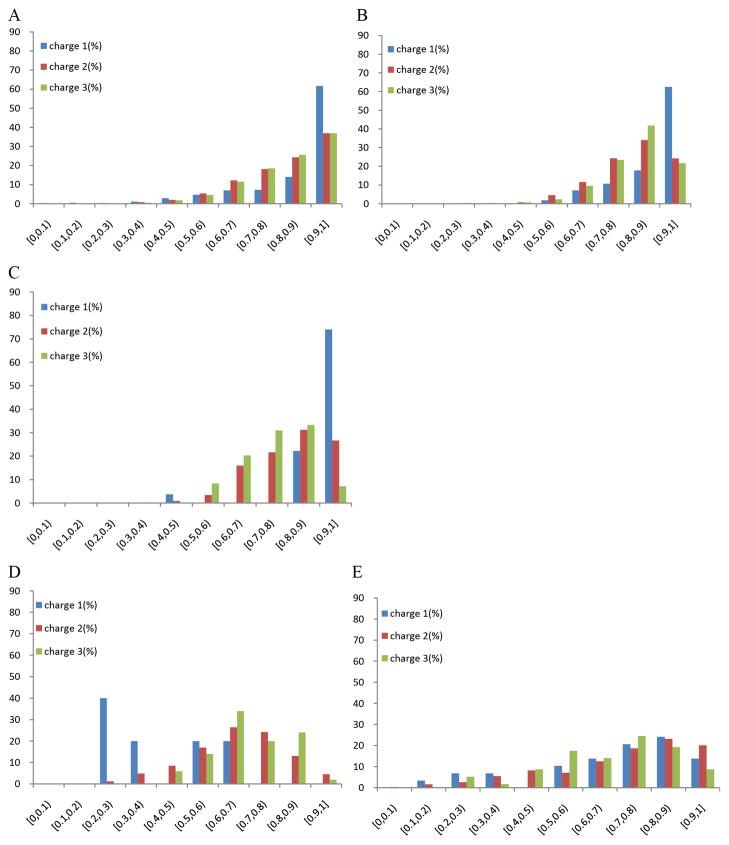

In Figure 1A–C shown are the distributions of correlation coefficients corresponding to the within-experiment replicated MS/MS spectra. Only unique peptides were considered; thus, all pairs of experimental spectra that were identified as the same peptide were averaged and counted as one. The bars in Figure 1A–C represent the distribution of correlation coefficients for replicates of tandem mass spectra for +1, +2, and +3 precursor ions in three data sets. Overall, the average correlation coefficients for +1, +2 and +3 peptides were estimated to be 0.868 (precursor charge state +1; 825 unique peptides), 0.821 (+2; 8513), 0.826 (+3; 2264) in data set Human, 0.882 (+1; 56), 0.808 (+2; 2500), 0.816 (+3; 595) in data set Mouse, and 0.925 (+1; 27), 0.809 (+2; 439), 0.762 (+3; 84) in data set Yeast. These results are also shown in Table 1 (column ReproducibilityW).

Figure 1.

Histograms of spectral reproducibility over peptides identified multiple times in the same experiment (A: Human, B: Mouse, C: Yeast), as well as the histograms of reproducibility for the unique peptides identified in two different experiments (D: Human vs. Mouse, E: Shewanella vs. Deinococcus).

Table 1.

The spectral similarity (± standard deviation) between experimental and predicted peptide fragmentation spectra on four different data sets. Spectral similarity was measured using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

| Human | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | MA | ARTHuman | ART | MA+ART | Baseline 1 | Baseline 2 | Baseline 3 | ReproducibilityW | ReproducibilityA |

| +1 | 0.380±0.244 | 0.554±0.213 | 0.481±0.213 | 0.552±0.210 | 0.179±0.081 | 0.217±0.104 | 0.444±0.210 | 0.868±0.178 | 0.404±0.161 |

| +2 | 0.602±0.217 | 0.654±0.182 | 0.644±0.187 | 0.658±0.169 | 0.226±0.077 | 0.323±0.112 | 0.444±0.149 | 0.821±0.147 | 0.658±0.148 |

| +3 | 0.509±0.222 | 0.561±0.164 | 0.553±0.163 | 0.574±0.152 | 0.197±0.072 | 0.209±0.099 | 0.329±0.101 | 0.826±0.152 | 0.693±0.120 |

| Mouse | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | MA | ARTMouse | ART | MA+ART | Baseline 1 | Baseline 2 | Baseline 3 | ReproducibilityW | ReproducibilityA |

| +1 | 0.663±0.212 | 0.662±0.156 | 0.676±0.157 | 0.698±0.161 | 0.271±0.099 | 0.374±0.121 | 0.504±0.180 | 0.882±0.106 | 0.404±0.161 |

| +2 | 0.582±0.222 | 0.596±0.199 | 0580±0.195 | 0.625±0.199 | 0.198±0.077 | 0.358±0.131 | 0.411±0.159 | 0.808±0.116 | 0.658±0.148 |

| +3 | 0.515±0.153 | 0.516±0.184 | 0.487±0.163 | 0.565±0.187 | 0.169±0.065 | 0.192±0.093 | 0.293±0.104 | 0.816±0.105 | 0.693±0.120 |

| Shewanella | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | MA | ARTShewanella | ART | MA+ART | Baseline 1 | Baseline 2 | Baseline 3 | ReproducibilityW | ReproducibilityA |

| +1 | 0.565±0.222 | 0.627±0.149 | 0.627±0.148 | 0.634±0.147 | 0.258±0.102 | 0.314±0.122 | 0.440±0.153 | N/A | 0.692±0.227 |

| +2 | 0.663±0.187 | 0.662±0.154 | 0.666±0.153 | 0.671±0.140 | 0.216±0.066 | 0.327±0.092 | 0.450±0.132 | N/A | 0.713±0.210 |

| +3 | 0.517±0.179 | 0.571±0.128 | 0.571±0.131 | 0.591±0.114 | 0.177±0.047 | 0.194±0.073 | 0.330±0.073 | N/A | 0.674±0.183 |

| Yeast | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | MA | ARTYeast | ART | MA+ART | Baseline 1 | Baseline 2 | Baseline 3 | ReproducibilityW | ReproducibilityA |

| +1 | 0.637±0.167 | 0.638±0.171 | 0.638±0.171 | 0.647±0.109 | 0.254±0.069 | 0.376±0.098 | 0.431±0.138 | 0.925±0.101 | N/A |

| +2 | 0.500±0.203 | 0.601±0.175 | 0.601±0.175 | 0.597±0.161 | 0.202±0.071 | 0.274±0.123 | 0.318±0.128 | 0.809±0.120 | N/A |

| +3 | 0.407±0.239 | 0.423±0.161 | 0.423±0.161 | 0.461±0.161 | 0.150±0.056 | 0.117±0.060 | 0.242±0.096 | 0.762±0.108 | N/A |

MA = MassAnalyzer, ART = PeptideART, ART(D) = PeptideART trained only on data set D, MA + ART = predictor constructed as an average of MassAnalyzer and PeptideART, Baseline 1–3 = three baseline methods referred to in the Materials and Methods section, ReproducibilityW = reproducibility within the same sample, ReproducibilityA = reproducibility across different experiments (Human vs. Mouse; Shewanella vs. Deinococcus). The values in bold indicate that the differences between PeptideART and MassAnalyzer are statistically significant with P < 0.004 (Wilcoxon test; Bonferroni-corrected value of 0.05).

For the cross-experiment analysis, we used identical peptides identified across Human and Mouse data sets, as well as Shewanella and Deinococcus data sets (Figure 1D–E; Table 1). Here, the average correlation coefficients were estimated to be 0.404 (precursor charge state +1; 5 unique peptide pairs), 0.658 (+2; 306), 0.693 (+3; 50) across Human and Mouse data sets, whereas the average correlation across Shewanella and Deinococcus data sets was estimated to be 0.692 (+1; 29), 0.713 (+2; 488), 0.674 (+3; 57). Although the number of identical peptides across the pairs of data sets was smaller, these results show a significant decrease in spectrum reproducibility of 15% or more compared to a within-experiment spectral reproducibility (P < 10−3; Wilcoxon test).

With respect to the specific fragment ion types, we observed that the neutral loss ions (e.g. b−H2O, y++−NH3) are generally less reproducible than the regular fragment ions (e.g. b, y++). Detailed per-ion results are shown in Tables S1–S2 (Supplementary Materials).

Prediction accuracy of computational models

Prediction accuracy was estimated for two predictors of peptide fragmentation spectra, MassAnalyzer28,29 and PeptideART.31 In addition, we estimated the performance of three ad-hoc predictors, referred to as Baseline-1, Baseline-2, Baseline-3, see Materials and Methods. Compared to its original version, PaptideART was retrained using similar features as in its original version, but using multi-output neural networks in order to account for the dependencies between fragment ions. Each output corresponds to a specific type of fragment ions (27 types, compared to 11 in the earlier work31). PeptideART was trained in two modes: (i) on a specific data set, and (ii) on a set of unique peptides over Human, Mouse, Shewanella and Yeast data sets. In each situation, the model was evaluated using 5-fold cross validation; thus no peptide was used both for training and testing in the same iteration. Peptides present in more than one data set were removed prior to training.

The correlation coefficients over the entire set of spectrum pairs are shown in Table 1. Somewhat surprisingly, the results indicate that the current predictors of peptide fragmentation spectra are within reach of the across-experiment spectral reproducibility (Table 1). In addition, both MassAnalyzer and PeptideART present significant improvements to any of the ad-hoc methods. Interestingly, data set-specific PeptideART was either less accurate or only marginally more accurate than the model trained over all data sets and this accuracy was significantly lower than the within-experiment spectral reproducibility. This indicates that data-driven models were not able to capture idiosyncrasies of each particular experiment, even if trained for this purpose. Rather, they seem to have learned data set independent rules of peptide fragmentation. Several examples of predicted spectra for MassAnalyzer and PeptideART are shown in Figure S1 (Supplementary Materials). In addition, the ROC curve-based comparisons between models are provided in Tables S3–S4 (Supplementary Materials).

Influence of training data on PeptideART

The accuracy of PeptideART was also estimated as a function of size of the training data. For a given data set size n, n tryptic peptides were selected uniformly randomly as training and evaluated on the remaining peptides from the combined Human, Mouse, and Shewanella data sets. To obtain more stable estimates, this strategy was repeated 10 times for each data set size and the accuracy was averaged.

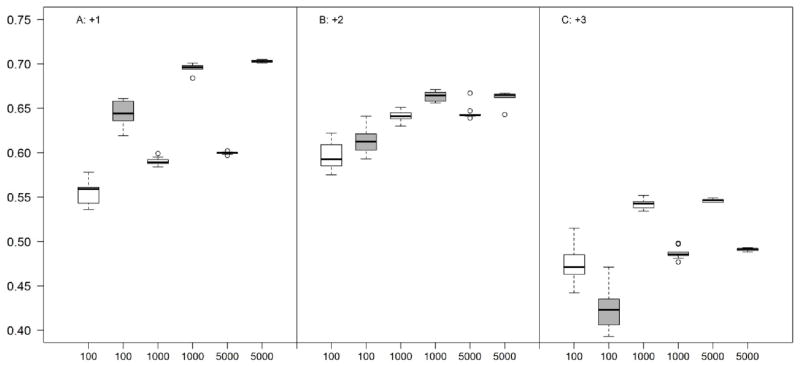

In Figure 2, shown is the Pearson correlation coefficient between predicted and experimental spectra with different number of peptides (n) chosen as training data. In addition to the standard correlation coefficient described in Materials and Methods (white boxes), here, we also estimated the correlation coefficient on the 27 ion types only between annotated ions of experimental and predicted spectra (shaded boxes). The results show that PeptideART is reasonably accurate when trained on as few as 100–200 peptides. This accuracy steadily increases with progressively larger data sets and plateaus at about 1000 peptides.

Figure 2.

Box plots showing the influence of data set size on PeptideART model for three charges of precursor ions (A: +1, B: +2, C: +3). White boxes represent correlation coefficient as described in Materials and Methods. Shaded boxes represent correlation coefficients over 27 fragment ion types only.

Running time of PeptideART

The running time of PeptideART was estimated on a set of 10000 randomly selected tryptic peptides from human. With about 0.04s per peptide, creating a library for the entire human genome (~0.5 million tryptic peptides) would roughly take 5 hours using a 2.66–3GHz CPU and a single-threaded process.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to estimate the reproducibility of low-energy CID-MS/MS fragmentation spectra, within and across different samples and platforms, as well as to evaluate the predictors currently available in the public domain. We found that the reproducibility of peptide fragmentation spectra from the same experiment is consistently very high (Pearson correlation coefficient around 0.85) and was consistent for each protease type. On the other hand, reproducibility across different experiments that use similar ion trap instruments was significantly lower, although still high (around 0.70). This high reproducibility of mass spectra supports peptide identification approaches that utilize spectral libraries19,21,22,38,39 over the generic strategies of modeling peptide fragmentation spectra.

We also evaluated two predictors of peptide fragment spectra, MassAnalyzer and PeptideART (with PeptideART retrained for this purpose). We found that their prediction accuracy is generally good but dependent on the charge state of the precursor peptide. The best prediction performance was achieved for singly and doubly charged precursor ions, followed by the triply charged precursors. This may be expected, since higher charge state spectra have more possible product ions, including multiply charged ones that may be formed from fragmentation events. Importantly, we estimated that the accuracy of the predicted spectra is relatively similar, with few exceptions, to the spectrum reproducibility across experiments. This strongly suggests that, in terms of accuracy of peptide identification, fragment spectrum predictors are good alternatives to spectral libraries, even with relatively small training data. We note that we used Pearson correlation coefficient as a primary measure of spectral similarity, but similar results were obtained when we applied a square root operation on raw peak intensities (Table S5, Supplementary Materials). Application of the square root function was previously shown to be a good pre-processing step for PSM algorithms.21,26

Computational models also offer several advantages over spectral libraries. Once trained, they require significantly less storage space than libraries of annotated spectra (e.g. there are >0.5 million human peptides only in the Swiss-Prot database40; if stored, their spectra would require more space than almost any trained machine learning model). In the context of database search, computational models provide theoretical spectra of complete proteomes (with decoy) and may impact the number and confidence of identified proteins and potentially even the estimation of false discovery rates. Finally, computational models can be trained for platforms where spectral libraries have low coverage. For example, even for the commonly used platforms such as CID, only 15% of human tryptic peptides (based on Swiss-Prot) have currently been stored in the NIST library of peptide fragmentation spectra (detailed data not shown).

Compared to MassAnalyzer that was developed based on the current understanding of peptide fragmentation pathways, PeptideART exploited large data sets of annotated spectra to achieve generally higher accuracy. This is not only useful for accurate peptide identification, but it also suggests that the chemistry of peptide fragmentation is difficult to model and not fully understood.

Materials and Methods

Data sets

Five data sets were used in this study. Mouse liver samples in data set Mouse were digested with trypsin and analyzed by 2D-LC-MS/MS using a ThermoFinnigan LTQ linear ion trap instrument. MASCOT was adopted to search against the IPI mouse v3.71 forward database combined with the reverse database. Peptides with MASCOT scores higher than 40 were selected: 18107 peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) were retained, of which 20 PSMs were identified from the reverse database (false discovery rate FDR = 0.22%, peptide level FDR = 0.64%). The final data set contained 67 unique peptides with charge +1, 3218 peptides with charge +2, and 883 peptides with charge +3.

The second data set, referred to as Shewanella, originally included a total of 28311 identified spectra (7175 +1, 17647 +2, and 3489 +3) from the Shewanella oneidensis and Deinococcus radiodurans proteomes13 collected using HPLC with LCQ ion trap instruments. The peptides were identified using SEQUEST. In order to ensure high quality of identified spectra (FDR not provided in the original paper), we applied new cutoffs to the set of peptide-spectrum matches (Xcorr = 2.0 for +1, Xcorr = 3.0 for +2, Xcorr = 4.0 for +3 peptides). The new data set contained 6010 +1, 11155 +2, and 1941 +3 peptides.

Data set Human comes from a human cell line.41 The MS/MS proteomics analyses were carried out on an extract of the erythroleukemia cell line K562 grown in suspension. After trypsin digestion, a multistage gradient delivered by an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to elute peptides into the electrospray ionization source of an LCQ ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoElectron, San Jose, CA). In this work, we used InsPecT42 to search against a database (IPI human v3.57 forward and reversed databases combined) which resulted in 84471 PSMs with P-values below 0.01. Among them, 63 PSMs were from the reversed database (FDR = 0.15%, peptide level FDR = 0.73%). The final data set included a total of 1259 +1 peptides, 11234 +2 peptides, and 3323 +3 peptides.

Data set Deinococcus, was created from 20 replicate analyses of the D. radiodurans proteome in our previous work.43 The D. radiodurans samples were digested using trypsin and the peptides were separated using nano-LC. The eluting peptides were electrosprayed into a ThermoFinigan LCQ Deca XP ion-trap mass spectrometer. The peptides were identified using MASCOT that searched forward and reverse D. radiodurans databases (FDR = 0.05%, peptide level FDR = 0.65%). This data set was used only to compare spectra of peptides identified both in Deinococcus and in Shewanella in order to estimate reproducibility of fragment spectra across different experiments.

The last data set, Yeast, was constructed from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant strain samples. The samples were digested using Glu-C to produce peptides terminated by aspartic or glutamic acid residues. The peptides in the digested sample were separated using a MudPIT experiment.44 The released peptides were electrosprayed into a ThermoFinnigan LTQ mass spectrometer. The PSMs were generated using SEQUEST followed by PeptideProphet45 with a probability cutoff of 0.95. The resulting number of unique peptides consisted of 39 +1 peptides, 707 +2 peptides, and 208 +3 peptides.

Computational approaches to predicting CID-MS/MS spectra of peptides

Two previously published methods were used to compare experimental and predicted spectra: (i) MassAnalyzer - an algorithm, introduced by Zhang,28,29 which explicitly models the understood model of peptide fragmentation with parameter optimization based on the training CID spectra; (ii) PeptideART - a neural network-based model designed to predict the probability that a particular fragment ion will be observed.31 PeptideART uses the outputted probabilities as estimates of the fragment ion intensities. For the purposes of this study, we retrained PeptideART using ensembles of 30 multi-output feed-forward neural networks, whereas the original version combined ensembles of single output networks. Thus, the retrained model better accounts for the dependencies between fragment ions. Additionally, we reduced the overall number of features (for speed), increased the number of predicted fragment ion types, and accommodated for the isotopic peaks using the method by Zhang.28

Features used to train PeptideART can be categorized in the following five groups: (i) peptide length and mass for the whole peptide as well as left and right fragment ions for a specific cleavage site; (ii) amino acid compositions for both fragments given the position of the cleavage site; (iii) physicochemical properties (basicity, helicity, hydrophobicity, pI) for both fragments;31 (iv) distances from the termini to the nearest residues P, H, K, and R in both fragments; and (v) N-terminal and C-terminal amino acid for both fragments. The total number of features is 158. We considered the following 27 fragment ions: precursor, precursor−H2O, precursor−NH3, b, b−H2O, b−NH3, b−H2O−NH3, b+H2O, a, a−H2O, a−NH3, y, y−H2O, y−NH3, y−H2O−NH3, b++, b++−H2O, b+++H2O, b++−NH3, a++, a++−H2O, a++−NH3, y++, y++−H2O, y++ −NH3, y+++, b+++. The doubly charged fragment ions were used for +2 and +3 precursor ions, while the triply charged fragment ions were used only for the +3 precursor ions.

In addition to MassAnalyzer and PeptideART, we also used three ad-hoc models. Baseline-1 model is the simplest scheme in which every possible fragment ion is assigned intensity of 1. Baseline-2 model outputs intensity of 1 for b- and y-ions, intensity of 0.5 for a-ions, intensity of 0.5 for ions with single neutral loss (e.g. b−H2O or y−NH3), intensity of 0.25 for double neutral loss ions (e.g. b−H2O−NH3), and intensity of 0.25 for doubly charged fragment ions b++ and y++. Finally, Baseline-3 model outputs the prior probabilities of occurrence for each ion type (see Table S6, Supplementary Materials, for details), thus outputting different values depending on the fragment ions under consideration. For example, in the Mouse data set, the b ions with intensity ≥1% of the total intensity were observed in 18.1% of cases, thus, in the theoretical spectrum, every b ion was assigned intensity of 0.181. For evaluation purposes, we used a publicly available version of MassAnalyzer, while PeptideART predictor was retrained using the data sets above and evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation on a set of unique peptides across different data sets.

Measuring similarity of fragment spectra

Two performance measures were used to assess the reproducibility of experimental spectra and the quality of predicting experimental spectra: (i) the Pearson correlation coefficient and (ii) the area under the ROC curve (AUC). In the case of reproducibility estimation, for each confidently identified peptide, the spectra matched to this peptide were selected, with all identifications being above the score threshold (based on false discovery rate, Xcorr, or PeptideProphet probability value). The reproducibility was estimated by averaging the correlation coefficients over all spectrum pairs for a particular peptide, and then further averaged over all unique peptides. Peptides identified based on a single matched spectrum, regardless of the score, were omitted. Therefore, data set Shewanella was not used for within-experiment reproducibility analysis because the authors included only the highest scoring spectrum for each peptide (i.e. spectral count for each peptide in Shewanella was 1). In the case of assessing the quality of prediction of fragment ions, we selected the highest scoring experimental spectrum for each peptide and then compared it with the predicted spectrum.

Correlation coefficient

Given two spectra, Sa and Sb, each spectrum was binned using 1200 bins in the m/z range from 200 to 2000 (the size of the bin was selected to correspond to the tolerance used to match fragment ions, ±0.8). The highest peak in each bin was selected to represent the bin; thus, each spectrum was encoded into a 1200-dimensional vector. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated between such pairs of 1200-dimensional vectors.

Area under the ROC curve

AUC was computed by assuming that spectrum Sa was the ‘correct’ spectrum and spectrum Sb was its ‘prediction’. Each fragment ion in Sa whose intensity was ≥1% of the total intensity of the spectrum was considered to be positive, while all other fragment ions were considered to be negative. A sliding threshold t, ranging from 0 to the maximum intensity (all spectra were normalized to 0–1 interval), was then applied to spectrum Sb to calculate sensitivity (sn, true positive rate) and specificity (sp, true negative rate). AUC was obtained as an area under the observed curve with (1 – sp) as the x-axis and sn as the y-axis, over the entire set of n pairs. While this approach gives more weight to longer peptides, it is a more stable estimate than an average of pairwise AUCs, given that a relatively small number of fragment ions comprise most of the total intensity of the spectrum.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

The number of unique identified peptides in each of the data sets.

| Charge | Human | Mouse | Shewanella | Dinococcus | Yeast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +1 | 1259 | 67 | 6010 | 31 | 39 |

| +2 | 11234 | 3218 | 11155 | 796 | 707 |

| +3 | 3323 | 883 | 1941 | 183 | 208 |

Acknowledgments

We thank Yong Fuga Li for assembling peptide identifications for the Deinococcus data set. We also thank Mark Goebl and Ross Cocklin; Quanhu Sheng; Vicki Wysocki; and Katheryn Resing for providing us with the Yeast, Mouse, Shewanella, and Human data sets, respectively. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 RR024236-01A1 and National Cancer Institute grant U24 CA126480-01. Finally, we thank the reviewers on their comments that improved the quality of this paper.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Additional information as noted in the text includes: 1) Examples of predicted spectra for MassAnalyzer and PeptideART; 2) Ion reproducibility analysis of experimental spectra; 3) ROC tables for PeptideART and MassAnalyzer; 4) Correlation coefficients for PeptideART and MassAnalyzer when square root was applied to peak intensities; 5) Prior probability tables in different data sets.

References

- 1.Dongre AR, Eng JK, Yates JR., 3rd Emerging tandem-mass-spectrometry techniques for the rapid identification of proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15(10):418–425. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR., 3rd An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yates JR, 3rd, Eng JK, McCormack AL, Schieltz D. Method to correlate tandem mass spectra of modified peptides to amino acid sequences in the protein database. Anal Chem. 1995;67(8):1426–1436. doi: 10.1021/ac00104a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(18):3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson RS, Davis MT, Taylor JA, Patterson SD. Informatics for protein identification by mass spectrometry. Methods. 2005;35(3):223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spicer V, Yamchuk A, Cortens J, Sousa S, Ens W, Standing KG, Wilkins JA, Krokhin OV. Sequence-specific retention calculator. A family of peptide retention time prediction algorithms in reversed-phase HPLC: applicability to various chromatographic conditions and columns. Anal Chem. 2007;79(22):8762–8768. doi: 10.1021/ac071474k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.May D, Fitzgibbon M, Liu Y, Holzman T, Eng J, Kemp CJ, Whiteaker J, Paulovich A, McIntosh M. A platform for accurate mass and time analyses of mass spectrometry data. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(7):2685–2694. doi: 10.1021/pr070146y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank AM, Bandeira N, Shen Z, Tanner S, Briggs SP, Smith RD, Pevzner PA. Clustering millions of tandem mass spectra. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(1):113–122. doi: 10.1021/pr070361e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Searle BC, Turner M, Nesvizhskii AI. Improving sensitivity by probabilistically combining results from multiple MS/MS search methodologies. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(1):245–253. doi: 10.1021/pr070540w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadygov R, Wohlschlegel J, Park SK, Xu T, Yates JR., 3rd Central limit theorem as an approximation for intensity-based scoring function. Anal Chem. 2006;78(1):89–95. doi: 10.1021/ac051206r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tabb DL, Fernando CG, Chambers MC. MyriMatch: highly accurate tandem mass spectral peptide identification by multivariate hypergeometric analysis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(2):654–661. doi: 10.1021/pr0604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Triscari JM, Pasa-Tolic L, Anderson GA, Lipton MS, Smith RD, Wysocki VH. Dissociation behavior of doubly-charged tryptic peptides: correlation of gas-phase cleavage abundance with ramachandran plots. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(10):3034–3035. doi: 10.1021/ja038041t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Triscari JM, Tseng GC, Pasa-Tolic L, Lipton MS, Smith RD, Wysocki VH. Statistical characterization of the charge state and residue dependence of low-energy CID peptide dissociation patterns. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5800–5813. doi: 10.1021/ac0480949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabb DL, Smith LL, Breci LA, Wysocki VH, Lin D, Yates JR., 3rd Statistical characterization of ion trap tandem mass spectra from doubly charged tryptic peptides. Anal Chem. 2003;75(5):1155–1163. doi: 10.1021/ac026122m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savitski MM, Kjeldsen F, Nielsen ML, Zubarev RA. Relative specificities of water and ammonia losses from backbone fragments in collision-activated dissociation. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(7):2669–2673. doi: 10.1021/pr070121z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barton SJ, Whittaker JC. Review of factors that influence the abundance of ions produced in a tandem mass spectrometer and statistical methods for discovering these factors. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2009;28(1):177–187. doi: 10.1002/mas.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hertz H, Hites RA, Biemann K. Identification of mass spectra by computer-searching a file of known spectra. Anal Chem. 1971;43(6):681–691. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ausloos P, Clifton CL, Lias SG, Mikaya AI, Stein SE, Tchekhovskoi DV, Sparkman OD, Zaikin V, Zhu D. The critical evaluation of a comprehensive mass spectral library. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1999;10(4):287–299. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(98)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yates JR, 3rd, Morgan SF, Gatlin CL, Griffin PR, Eng JK. Method to compare collision-induced dissociation spectra of peptides: potential for library searching and subtractive analysis. Anal Chem. 1998;70(17):3557–3565. doi: 10.1021/ac980122y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig R, Cortens JP, Beavis RC. The use of proteotypic peptide libraries for protein identification. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19(13):1844–1850. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frewen BE, Merrihew GE, Wu CC, Noble WS, MacCoss MJ. Analysis of peptide MS/MS spectra from large-scale proteomics experiments using spectrum libraries. Anal Chem. 2006;78(16):5678–5684. doi: 10.1021/ac060279n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam H, Deutsch EW, Eddes JS, Eng JK, King N, Stein SE, Aebersold R. Development and validation of a spectral library searching method for peptide identification from MS/MS. Proteomics. 2007;7(5):655–667. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam H, Deutsch EW, Eddes JS, Eng JK, Stein SE, Aebersold R. Building consensus spectral libraries for peptide identification in proteomics. Nat Methods. 2008;5(10):873–875. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang H, Arnold RJ, Alves P, Xun Z, Clemmer DE, Novotny MV, Reilly JP, Radivojac P. A computational approach toward label-free protein quantification using predicted peptide detectability. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(14):e481–e488. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuster B, Schirle M, Mallick P, Aebersold R. Scoring proteomes with proteotypic peptide probes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(7):577–583. doi: 10.1038/nrm1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bern M. Peptide identification using both spectrum libraries and protein databases. Proceedings of the 8th Annual International Conference on Computational Systems Bioinformatics; 2009. pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahrne E, Masselot A, Binz PA, Muller M, Lisacek F. A simple workflow to increase MS2 identification rate by subsequent spectral library search. Proteomics. 2009;9(6):1731–1736. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z. Prediction of low-energy collision-induced dissociation spectra of peptides. Anal Chem. 2004;76(14):3908–3922. doi: 10.1021/ac049951b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z. Prediction of low-energy collision-induced dissociation spectra of peptides with three or more charges. Anal Chem. 2005;77(19):6364–6373. doi: 10.1021/ac050857k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elias JE, Gibbons FD, King OD, Roth FP, Gygi SP. Intensity-based protein identification by machine learning from a library of tandem mass spectra. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(2):214–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnold RJ, Jayasankar N, Aggarwal D, Tang H, Radivojac P. A machine learning approach to predicting peptide fragmentation spectra. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2006:219–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barton SJ, Richardson S, Perkins DN, Bellahn I, Bryant TN, Whittaker JC. Using statistical models to identify factors that have a role in defining the abundance of ions produced by tandem MS. Anal Chem. 2007;79(15):5601–5607. doi: 10.1021/ac0700272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klammer AA, Reynolds SM, Bilmes JA, MacCoss MJ, Noble WS. Modeling peptide fragmentation with dynamic Bayesian networks for peptide identification. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(13):i348–356. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank AM. Predicting intensity ranks of peptide fragment ions. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(5):2226–2240. doi: 10.1021/pr800677f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venable JD, Yates JR., 3rd Impact of ion trap tandem mass spectra variability on the identification of peptides. Anal Chem. 2004;76(10):2928–2937. doi: 10.1021/ac0348219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabb DL, MacCoss MJ, Wu CC, Anderson SD, Yates JR., 3rd Similarity among tandem mass spectra from proteomic experiments: detection, significance, and utility. Anal Chem. 2003;75(10):2470–2477. doi: 10.1021/ac026424o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tabb DL, Thompson MR, Khalsa-Moyers G, VerBerkmoes NC, McDonald WH. MS2Grouper: group assessment and synthetic replacement of duplicate proteomic tandem mass spectra. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16(8):1250–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craig R, Cortens JC, Fenyo D, Beavis RC. Using annotated peptide mass spectrum libraries for protein identification. J Proteome Res. 2006;5(8):1843–1849. doi: 10.1021/pr0602085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, Bell AW, Bergeron JJ, Yanofsky CM, Carrillo B, Beaudrie CE, Kearney RE. Methods for peptide identification by spectral comparison. Proteome Science. 2007;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bairoch A, Apweiler R, Wu CH, Barker WC, Boeckmann B, Ferro S, Gasteiger E, Huang H, Lopez R, Magrane M, Martin MJ, Natale DA, O’Donovan C, Redaschi N, Yeh LS. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33 doi: 10.1093/nar/gki070. Database Issue:D154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Resing KA, Meyer-Arendt K, Mendoza AM, Aveline-Wolf LD, Jonscher KR, Pierce KG, Old WM, Cheung HT, Russell S, Wattawa JL, Goehle GR, Knight RD, Ahn NG. Improving reproducibility and sensitivity in identifying human proteins by shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76(13):3556–3568. doi: 10.1021/ac035229m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanner S, Shu H, Frank A, Wang LC, Zandi E, Mumby M, Pevzner PA, Bafna V. InsPecT: identification of posttranslationally modified peptides from tandem mass spectra. Anal Chem. 2005;77(14):4626–4639. doi: 10.1021/ac050102d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li YF, Arnold RJ, Tang H, Radivojac P. The importance of peptide detectability for protein identification, quantification, and experiment design in MS/MS proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(12):6288–6297. doi: 10.1021/pr1005586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radivojac P, Vacic V, Haynes C, Cocklin RR, Mohan A, Heyen JW, Goebl MG, Iakoucheva LM. Identification, analysis, and prediction of protein ubiquitination sites. Proteins. 2010;78(2):365–380. doi: 10.1002/prot.22555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74(20):5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.