Abstract

Mutations in the gene encoding of the catalytic subunit of mtDNA polymerase gamma (POLG1) can cause typical Alpers' syndrome. Recently, a new POLG1 mutation phenotype was described, the so-called juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome. This POLG1 mutation phenotype is characterized by refractory epilepsy with recurrent status epilepticus and episodes of epilepsia partialis continua, which often necessitate admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and pose an important mortality risk. We describe two previously healthy unrelated teenage girls, who both were admitted with generalized tonic-clonic seizures and visual symptoms leading to a DNA-supported diagnosis of juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome. Despite combined treatment with anti-epileptic drugs, both patients developed status epilepticus requiring admission to the ICU. Intravenous magnesium as anti-convulsant therapy was initiated, resulting in clinical and neurophysiological improvement and rapid extubation of both patients. Treating status epilepticus in juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome with magnesium has not been described previously. Given the difficulties encountered while treating epilepsy in patients with this syndrome, magnesium therapy might be considered.

Keywords: Alpers' syndrome, POLG1, Magnesium, Status epilepticus, Adolescence

Introduction

Polymerase gamma is essential for mitochondrial DNA replication. Mutations in the nuclear gene encoding the catalytic subunit of mtDNA polymerase gamma (POLG1) are associated with mitochondrial diseases [1]. POLG1 mutations have been implicated in progressive external ophthalmoplegia [2], sensory ataxic neuropathy [3], parkinsonism [4], premature menopause [4], Alpers' syndrome [5, 6], and mixed phenotypes [7, 8]. There appears no strict relationship between phenotype and genotype in patients with pathogenic mutations in the gene that encodes for POLG1 [8].

Alpers' syndrome usually presents in early childhood with the classical triad of developmental delay, intractable seizures and hepatic failure, which may be precipitated by valproic acid [3, 5–8]. In 2008, a new POLG1 mutation phenotype was described, features of which are refractory epilepsy and visual symptoms in previously healthy adolescents or young adults, the so-called juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome [9, 10]. Both Alpers' phenotypes are characterized by refractory epilepsy with recurrent status epilepticus and episodes of epilepsia partialis continua, which often necessitate admission to the intensive-care unit (ICU) and pose an important mortality risk [10].

Intravenous magnesium is the first choice agent in treating convulsions in eclampsia [11], and may be effective in status epilepticus of other origin, although reports on this topic are sparse [12–14]. We present two cases of non-related teenage girls with juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome due to POLG1 mutations who presented with refractory seizures that originated in the occipital lobe and were eventually successfully treated with magnesium.

Case 1

A previously healthy 19-year-old woman was admitted to our tertiary care center after two generalized tonic clonic seizures in a fortnight. Since the first seizure, she complained of seeing bright spots. Routine neurological examination and brain-CT at admission showed no abnormalities. Visual field examination revealed a right-sided homonymous paracentral scotoma. FLAIR and T2-weighted MRI showed bilateral lesions with increased signal intensity in the occipital cortex, most prominent in the left hemisphere, with areas of both increased and decreased diffusion on ADC maps. EEG showed slowing of the background activity and continuous epileptic activity over the occipital areas, also most prominent in the left hemisphere. Her visual symptoms were therefore interpreted as focal occipital status epilepticus. Treatment with phenytoin and continuous intravenous infusion of clonazepam were initiated. This improved the visual complaints but they did not resolve completely.

Five weeks after the first seizure, while still on phenytoin and clonazepam she experienced right-sided focal motor seizures that only partially responded to additional therapy with clobazam and levetiracetam. Since a POLG1 mutation syndrome was suspected, valproic acid was avoided. Treatment with midazolam resulted in temporary resolution of focal convulsions, but her visual complaints did not improve and ictal activity persisted on EEG with right-sided hemiparesis. Her mental status deteriorated as she became disoriented, with dysphasia and acalculia. Repeated MRI showed an increase in the extent and number of the cortical occipital lesions, now including left-sided pulvinar thalamic abnormalities. Urgent DNA analysis indeed revealed a homozygous (A467T) mutation of the POLG1-gene confirming the diagnosis of juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome.

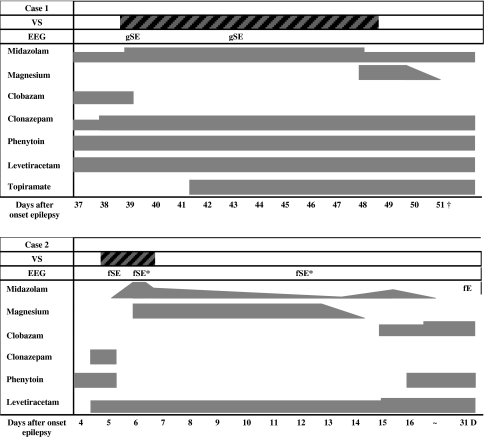

Her condition worsened as she developed frequent simple left-sided partial motor seizures, which gradually transformed into generalized status epilepticus. She was admitted to the ICU and treated with high-dose intravenous midazolam (0.4 mg/kg/h), and a combination of phenytoin (300 mg/day i.v.), clonazepam (3 mg/day i.v.) and levetiracetam (1,500 mg/day i.v.), and ventilatory support (Fig. 1). When sedation was tempered, the seizures immediately returned. High-dose oral topiramate (1,000 mg/day) somewhat decreased the frequency of the seizures but the EEGs remained highly abnormal, showing encephalopathic changes with continuous epileptic activity. Magnesium infusion was then introduced, aiming to increase serum levels from 0.81 mmol/l to approximately 3.5 mmol/l, leading almost instantly to complete abolishment of her clinical seizures. Midazolam was tapered, and she was extubated the following day. At time of extubation, serum magnesium level was 3.8 mmol/l. After extubation, she was able to communicate, although she remained somnolent.

Fig. 1.

Timetable with overview of anti-epileptic drugs. D discharge from hospital; fE focal epileptiform discharges; fSE focal status epilepticus; gSE generalized status epilepticus; VS ventilatory support; *Improved compared to previous EEG; †Died

Although clinical signs of seizures remained absent, the patient developed sepsis, probably due to ventilator associated pneumonia, leading to multi-organ failure and death 2 weeks after admission to the ICU.

Case 2

In December 2008, a previously healthy 17-year-old girl complained of impaired vision and light flashes for several weeks. She was evaluated in another hospital after a 15-min episode of confusion and suspected convulsions. She fully recovered and was diagnosed with migraine. Two days later, she had two generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and was admitted to our hospital. Neurological examination revealed dysphasia, right-sided hemiparesis and intermittent partial motor seizures of her right leg. T2 and FLAIR MRI showed hyperintense lesions of the left occipital cortex, thalamus, and mesial temporal lobe. One week after admission, DNA analysis revealed a homozygous A467T mutation of the POLG1-gene, confirming the suspected diagnosis of juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome. Fourteen years earlier, her teenage sister had generalized status epilepticus. She died without an established diagnosis after a complicated brain biopsy.

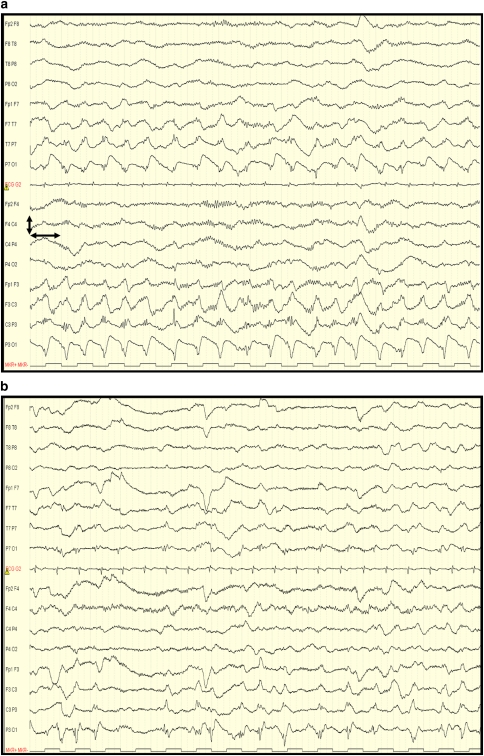

While being treated with phenytoin (Fig. 1), her EEG showed a continuing focal status epilepticus of the left occipital region, spreading anteriorly. Continuous intravenous infusion of midazolam and levetiracetam were added and she was admitted to the ICU for ventilatory support. When high-dose midazolam (0.3 mg/kg/h), levetiracetam (2,000 mg/day i.v.), and phenytoin (300 mg/day i.v.) could not abolish focal status epilepticus, magnesium infusion was started, aiming to increase serum levels from 0.85 mmol/l to approximately 3.5 mmol/l. Paresis and dysphasia both gradually improved within hours after the start of magnesium infusion and within 12 h midazolam was tapered and she was extubated with at that time a serum magnesium level of 2.0 mmol/l. EEG after extubation showed improvement, although there was still a focal occipital status epilepticus (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

a (case 2): EEG before magnesium infusion. Despite midazolam, levetiracetam, and phenytoin, there is an ongoing status epilepticus of the left hemisphere. b (case 2): EEG about 10 h after the start of magnesium infusion. There is a marked loss of rhythmicity and improved background over the left and right hemisphere. Left and right arrow 1 s; up and down arrow 200 μV

When magnesium was tapered and midazolam was discontinued, focal convulsions of her right arm recurred, for which midazolam (0.1 mg/kg/h) was restarted in addition to magnesium, phenytoin, and clobazam. Convulsions ceased and the right-sided (post-)ictal paresis and dysphasia disappeared. Gradually, midazolam and magnesium were stopped and oral phenytoin, clobazam, and levetiracetam were continued. The patient could be discharged 1 month after admission, and she remains without seizures up to now, 8 months after discharge. Her EEG at discharge showed subtle focal occipital epileptic discharges, although there was an obvious improvement compared to previous EEGs.

Discussion

Juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome is characterized by refractory epilepsy, predominating in the occipital lobe, with frequent episodes of spreading and status epilepticus, for which a combination of several anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) is often required [10]. Benzodiazepines are the main-stay in the treatment of status epilepticus, but often necessitate ventilatory support. Importantly, valproic acid should be avoided, since it carries a high risk of inducing hepatic failure. In our own experience, propofol and thiopental may also lead to hepatic failure and rapid neurological deterioration in children with Alpers' syndrome. In juvenile-onset patients with POLG1 mutations, these drugs should perhaps also be avoided. When the combination of several high-dose AEDs could not stop focal or generalized status epilepticus in our two patients, we chose to add magnesium according to the use in (pre-)eclampsia [11]. The anticonvulsive effect of magnesium has been well established in (pre-)eclampsia, but it is rarely used in the treatment of epilepsy of other origin. In (pre-)eclampsia, an immediate effect is pursued by a loading dose of magnesium sulphate followed by continuous infusion for 24 h, resulting in serum magnesium levels of 1.7–3.5 mmol/l [15], but even at these high doses, side-effects are mild and sparse [11, 16]. In particular, renal or hepatic failure due to high-dose magnesium therapy have not been described. Although magnesium is effective in preventing and treating eclampsia, its mechanism of action remains unclear. One of the suggested anticonvulsant mechanisms is its action as a N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA-) receptor antagonist. The NMDA-receptor is a glutamate receptor which, when activated, leads to a massive depolarization of neuronal networks and bursts of action potentials. Magnesium may act to increase the seizure threshold by blocking the NMDA-receptors [15]. Animal models suggest that AEDs enhancing GABA-receptor activation (e.g., barbiturates and benzodiazepines) are effective in the treatment of status epilepticus but resistance often develops over prolonged status epilepticus. Ketamine, which is also an NMDA-receptor antagonist, however, showed no effect when administered within the hour after onset of status epilepticus, but was effective in treating prolonged status epilepticus, suggesting a shift from inadequate GABA-ergic inhibition to excessive glutamergic excitation in refractory status epilepticus [17, 18]. Magnesium also acts as a voltage-dependent calcium channel antagonist and prevents membrane depolarizations, which could be an additional mechanism of anti-epileptic action [19].

The potential use of magnesium in epilepsy is adapted from practice in eclampsia [11]. While magnesium as an anticonvulsant agent has been tested to be safe in (pregnant) women, the safety of using magnesium for treating epilepsy in adolescents with juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome has not been studied. We cannot of course be certain that the magnesium infusion was the key factor in terminating otherwise refractory status in our two patients, particularly in the second case who resolved some hours later. However, the timing in the first, together with biological plausibility, is persuasive. Given the difficulties encountered while treating refractory status epilepticus in patients with juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome, and the potential danger of some commonly used antiepileptic drugs in this syndrome, additional magnesium therapy should be considered.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Hudson G, Chinnery PF (2006) Mitochondrial DNA polymerase-gamma and human disease. Hum Mol Genet 15 Spec No. 2:R244–R252 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.van Goethem G, Dermaut B, Lofgren A, Martin JJ, van Broekhoven C. Mutation of POLG is associated with progressive external ophthalmoplegia characterized by mtDNA deletions. Nat Genet. 2001;28:211–212. doi: 10.1038/90034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Goethem G, Luoma P, Rantamaki M, et al. POLG mutations in neurodegenerative disorders with ataxia but no muscle involvement. Neurology. 2004;63:1251–1257. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140494.58732.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luoma P, Melberg A, Rinne JO, et al. Parkinsonism, premature menopause, and mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma mutations: clinical and molecular genetic study. Lancet. 2004;364:875–882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naviaux RK, Nguyen KV. POLG mutations associated with Alpers’ syndrome and mitochondrial DNA depletion. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:706–712. doi: 10.1002/ana.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrari G, Lamantea E, Donati A, et al. Infantile hepatocerebral syndromes associated with mutations in the mitochondrial DNA polymerase-gammaA. Brain. 2005;128:723–731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzoulis C, Engelsen BA, Telstad W, et al. The spectrum of clinical disease caused by the A467T and W748S POLG mutations: a study of 26 cases. Brain. 2006;129:1685–1692. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvath R, Hudson G, Ferrari G, et al. Phenotypic spectrum associated with mutations of the mitochondrial polymerase gamma gene. Brain. 2006;129:1674–1684. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uusimaa J, Hinttala R, Rantala H, et al. Homozygous W748S mutation in the POLG1 gene in patients with juvenile-onset Alpers' syndrome and status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1038–1045. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelsen BA, Tzoulis C, Karlsen B, et al. POLG1 mutations cause a syndromic epilepsy with occipital lobe predilection. Brain. 2008;131:818–828. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Which anticonvulsant for women with eclampsia? Evidence from the Collaborative Eclampsia Trial (1995) Lancet 345:1455–1463 [PubMed]

- 12.Robakis TK, Hirsch LJ. Literature review, case report, and expert discussion of prolonged refractory status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2006;4:35–46. doi: 10.1385/NCC:4:1:035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadeh M, Blatt I, Martonovits G, Karni A, Goldhammer Y. Treatment of porphyric convulsions with magnesium sulfate. Epilepsia. 1991;32:712–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1991.tb04714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durham D. Management of status epilepticus. Crit Care Resusc. 1999;1:344–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Euser AG, Cipolla MJ. Magnesium sulfate for the treatment of eclampsia: a brief review. Stroke. 2009;40:1169–1175. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.527788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Do women with pre-eclampsia, and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulphate? The magpie trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877–1890. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08778-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borris DJ, Bertram EH, Kapur J. Ketamine controls prolonged status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2000;42:117–122. doi: 10.1016/S0920-1211(00)00175-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen JW, Wasterlain CG. Status epilepticus: pathophysiology and management in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:246–256. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Bergh WM, Dijkhuizen RM, Rinkel GJ. Potentials of magnesium treatment in subarachnoid haemorrhage. Magnes Res. 2004;17:301–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]