Abstract

Women have long strived to possess long, thick, and dark eyelashes. Prominent eyes and eyelashes are often considered a sign of beauty and can be associated with increased levels of attractiveness, confidence, and well-being. Numerous options may improve the appearance of eyelashes. Mascara aims to temporarily darken, lengthen, and thicken eyelashes using a combination of waxes, pigments, and resins. Artificial eyelashes can be adhered either to the dermal margin or to individual eyelashes. Individuals may even use eyelash transplantations to improve the appearance of their eyelashes. The unique properties of eyelashes (e.g., relatively long telogen and short anagen phases compared with scalp hairs, slow rate of growth, and a lack of influence by androgens) may allow for specific aesthetic interventions to improve the appearance of natural eyelashes. Some over-the-counter (OTC) products may contain prostaglandin analogs that can affect eyelash growth, but neither the safety nor efficacy of these OTC cosmetics has been fully studied. Originally indicated for the reduction of intraocular pressure, the synthetic prostaglandin analog bimatoprost was recently approved for the treatment of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes. In a double-blinded, randomized, vehicle-controlled trial, bimatoprost safely and effectively grew natural eyelashes, making them longer, thicker, and darker. Bimatoprost was generally safe and well tolerated and appears to provide an additional option for individuals looking to improve the appearance of their eyelashes.

Keywords: Eyelashes, Bimatoprost, Prostaglandin analog, Mascara, Aesthetics

Introduction

Since ancient times, physical beauty has been considered an advantageous and sought-after trait [1]. Although the definition of beauty varies over time and from culture to culture, the face and the eyes in particular are recognized as important contributors to physical beauty [1, 2]. Beautiful eyes are associated with social advantages [1]. Eyelashes that are long and thick are considered a sign of beauty in many cultures and often have a positive psychological effect on women [3–6]. To enhance the overall prominence of their eyelashes, women have employed a number of techniques, some dating back millennia [7].

Presently, many women rely on makeup or over-the-counter (OTC) cosmetics to enhance the appearance of their eyelashes. As of 2005, the global cosmetics and toiletries market totaled $155 billion and color cosmetics (e.g., eye makeup, facial makeup, lip products, and nail products) comprised 15% of that market or approximately $24 billion (Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA, unpublished data). Eye makeup, which includes eye shadow, eye liner, and mascara, represents the fastest-growing category of color cosmetics in the U.S., with a growth rate of more than 6% in 2005. In the U.S. alone, the annual mascara market is estimated at $1.1 billion (Allergan, Inc., unpublished data). Mascara can provide women with increased eyelash volume, longer, darker lashes, and improved curl [7; Allergan, Inc., unpublished data].

In addition to makeup, the effects of which are temporary and subject to smudging, women have several longer-lasting and sometimes permanent options for improving the appearance of their eyelashes, including eyelash extensions and eyelash transplants [8, 9]. Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% (Latisse®, Allergan Inc., Irvine, CA), a synthetic prostaglandin analog, to increase the length, thickness, and darkness of eyelashes in people with hypotrichosis of the eyelashes (i.e., inadequate or not enough eyelashes) (Latisse package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2008).

Anatomy and Physiology of Eyelashes

Beyond their aesthetic and social functions, eyelashes serve a protective function by defending the eye against debris and triggering the blink reflex [10–12]. People generally have between 100 and 150 lashes emanating from each of their upper eyelids [11, 12]. Lower eyelashes are half as numerous as upper eyelashes [11]. Upper eyelashes are arranged in two to three rows. Similar to scalp hair, eyelashes are considered terminal hairs, and as such are coarser, longer, and more pigmented than other hair types (i.e., vellus and intermediate) [13]. Eyelashes are wider than scalp hairs and, unlike other hair types, do not typically lose pigmentation and become gray with age. Eyelashes are distinct from all other hairs on the body in that they lack an accompanying arrector pili muscle, and, unlike many other hairs, are not influenced by androgens [13, 14].

As is true for all hair follicles on the body, all eyelash follicles are present at birth and their numbers do not increase during life [13, 15]. The hair follicles of many mammals exhibit synchronous hair cycles, but in humans the hair cycle is asynchronous such that some hair follicles are growing while others are dormant [13]. The hair cycle for all hair types is divided into the phases of anagen, catagen, and telogen, but the average length of the cycle and the individual phases varies by body location.

Though variable, the normal eyelash cycle is estimated to last from 5 to 11 months (Fig. 1a) (Latisse package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2008, and unpublished data) [13, 16, 17]. The growth phase of eyelash follicles, anagen, lasts approximately 1–2 months. During anagen, in addition to growth, melanogenesis and the subsequent transfer of pigment to the hair shaft also occurs [13]. The duration of anagen crucially impacts hair length [10]. Anagen is a period of rapid cell proliferation and differentiation [18]. Following anagen, eyelash follicles enter catagen, a transition phase, which lasts approximately 15 days and is the time during which epithelial elements of the follicle undergo apoptosis or programmed cell death [13]. The longest phase of the normal eyelash cycle, telogen or the resting phase, lasts approximately 4–9 months [13, 16, 17]. Throughout telogen, no significant cell differentiation, proliferation, or apoptosis occurs [18]. Expulsion of the previous hair (i.e., exogen) takes place during the transition between telogen and anagen [10, 14].

Fig. 1.

a Hair cycle of normal eyelashes. b Potential mechanisms of action of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% on the eyelash cycle [13, 16, 17] (Latisse package insert and unpublished data, Allergan, Inc.)

In contrast to eyelashes, scalp follicles have a much longer cycle, lasting several years [14, 15]. Anagen alone can last up to 6–7 years for scalp hairs [13–15]. Relative differences in the lengths of the hair cycle phases of eyelashes and scalp hair result in approximately 50% of upper eyelash follicles being in telogen at any given time compared with only 5% to 15% of scalp follicles [13–16]. Furthermore, eyelashes are typically slow-growing hairs, growing at a rate of approximately 0.15 mm/day [17] compared with 0.3–0.4 mm/day for scalp hair [16–18]. The unique properties of the eyelash cycle differentiate eyelashes from other body hairs and may cause drugs that affect hair growth in one location to enhance eyelash prominence.

Surgical/Procedural Options

Artificial eyelashes are synthetic or donated human eyelashes that give the visual appearance of longer eyelashes. Strips of artificial lashes can easily be adhered to the upper eyelid [8]. As intimated by the nickname “falsies,” such lashes may not result in a natural appearance. Alternatively, single eyelash extensions can be attached to individual eyelashes [8, 19]. The procedure requires an hour and a half to complete and can cost as much as $500 [19]. Artificial eyelashes are typically held in place by methacrylate-based adhesives that can result in allergic contact dermatitis [8]. Similarly, the solvent used to remove artificial eyelashes can also cause an allergic reaction in some individuals. Depending on the type of artificial lash and the procedure used to adhere them, artificial eyelashes can remain in place from several days to several weeks [8, 19]. Lash Extender (myofibril-styled eyelash extensions applied by the patient) is another option.

Successful eyelash transplantations have been reported in the medical literature, although their use in the absence of congenital eyelash defects or a need for reconstruction is controversial [9]. Eyelash transplantations transfer hair follicles from the scalp onto the margins of the eyelid. Because these transplanted lashes retain the qualities of scalp hair, patients must regularly trim and curl the implanted lashes [9, 20]. Complications of eyelash transplantation include pain, bleeding, thick scar formation, numbness, eyelid ptosis, and blindness [9].

Prescription Options

Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% is the only FDA-approved product to safely and effectively enhance the growth of a patient’s own eyelashes. Bimatoprost is a synthetic prostamide, or prostaglandin ethanolamide, analog approved in 2001 for the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension (Lumigan package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2006). In one clinical trial, when administered as an eye drop for the treatment of glaucoma, eyelash growth was noted in 42.6% of patients treated with bimatoprost once daily for a year [21]. Although such growth was recorded as an adverse event, the potential aesthetic benefits of eyelash growth were recognized and led to the development and testing of bimatoprost as a product designed to increase eyelash prominence. When prescribed to enhance eyelash prominence, bimatoprost is accompanied by sterile, single-use-per-eye applicators and should be applied once daily to the skin of the upper eyelid margin at the base of the eyelashes (Latisse package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2008).

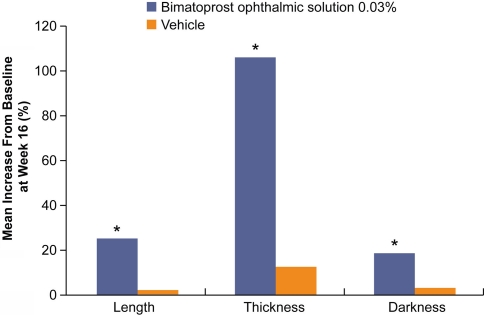

The safety and efficacy of once-daily bimatoprost 0.03% solution in increasing overall eyelash prominence following dermal administration to the upper-eyelid margins was evaluated in a recent multicenter, double-blinded, randomized, vehicle-controlled, parallel study of 278 adult patients [22]. Starting at 8 weeks of treatment, bimatoprost was associated with significantly greater increases in overall eyelash prominence than vehicle as measured by at least a one-grade increase on the four-grade Global Eyelash Assessment (GEA) scale. These changes were sustained throughout the remainder of the treatment period (16 weeks) and, at week 16, 78.1% of subjects treated with bimatoprost exhibited at least a one-grade increase from baseline in GEA score compared with 18.4% of patients treated with vehicle (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Improvements in GEA scores continued to favor bimatoprost 4 weeks after discontinuation of treatment (i.e., the post-treatment visit at week 20). In the same study, efficacy was assessed by digital image analysis of superior-view eyelash photographs taken with standardized equipment and after uniform subject preparation at all visits. As assessed by such analysis, at week 16 bimatoprost treatment was associated with a mean 25% increase in eyelash length vs. 2% for vehicle, a mean 106% increase in eyelash thickness vs. 12% for vehicle, and a mean 18% increase in eyelash darkening vs. 3% for vehicle (Fig. 3). Subjects treated with bimatoprost for eyelash growth also reported feeling significantly more satisfied with their eyelashes, more confident in their looks, more attractive, more professional, and more satisfied with their daily routine than those subjects receiving vehicle as assessed by patient-reported outcome questionnaires.

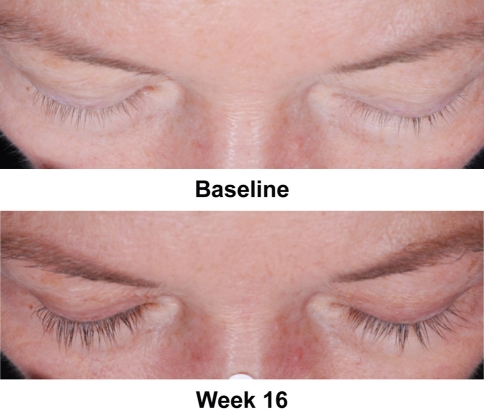

Fig. 2.

Sample images of patient eyelashes before and after 16 weeks of once-daily bimatoprost treatment. The patient entered the study with a baseline overall eyelash prominence assessed as moderate (grade 2) on the Global Eyelash Assessment (GEA) scale. After 16 weeks of double-blind treatment with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03%, the patient’s eyelashes were markedly prominent (i.e., GEA score of 3). In determining GEA scores, raters utilized a photonumeric guide and evaluated overall eyelash prominence, including length, fullness, and color of both upper eyelashes, with length considered the most important feature

Fig. 3.

Changes in eyelash length, thickness, and darkness associated with bimatoprost in a double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial [22]. Eyelash qualities were assessed by digital image analysis based on superior-view digital eyelash photographs taken with standardized equipment and subject preparation. Last observation carried forward was performed on weeks 1–16. * P < 0.0001 vs. placebo based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test

Although the mechanism by which bimatoprost enhances eyelash growth has not been fully elucidated, it is believed to increase the percentage of lash follicles in and the duration of anagen (Fig. 1b) (Latisse package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2008). Bimatoprost also appears capable of stimulating melanogenesis [23], which likely explains the changes in the pigmentation of eyelashes observed with use. The duration of the effect of bimatoprost on eyelashes is not fully known and has not been evaluated beyond 4 weeks post-treatment. Furthermore, the ability of bimatoprost to affect the growth of eyelashes in patients with systemic diseases or eyelash loss has not been evaluated.

The safety of bimatoprost, applied either dermally or as an eye drop, has been demonstrated in numerous trials [21, 24]. When applied as an eye drop (i.e., for the treatment of ocular hypertension), bimatoprost was generally well tolerated with long-term use for up to 4 years [24]. Other than eyelash growth, the most common adverse events reported when bimatoprost is instilled into the eye include conjunctival hyperemia, eye pruritus, eye dryness, a burning sensation in the eye, eyelid pigmentation, foreign body sensation, eye pain, and visual disturbance [21, 24; Lumigan package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2006]. Although rare, bimatoprost when applied as an eye drop has also been associated with increases in iris pigmentation, which are generally thought to be permanent [25]; Lumigan package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2006]. While iris pigmentation was not seen in the controlled clinical studies with dermal application for eyelash growth, there have been a small number of post-marketing reports of iris pigmentation following use of bimatoprost for eyelash growth (data on file, Allergan Medical Affairs, June 2010). Post-marketing reports are often incomplete and difficult to evaluate on an individual basis. However, to date there have been no identified trends of risk factors reported in these small numbers of cases. Patients should be advised of the small potential for increased brown iris pigmentation which is likely to be permanent. Infection following application is also a possibility and should be limited by following the package insert instructions for application with daily single-dose applicators for each eye, which are provided with each package.

Although clinical experience regarding the safety of bimatoprost 0.03% applied dermally is limited, available data suggest that the safety profile may be even more favorable than that described above for intraocular administration. In the pivotal trial, the most common adverse events associated with bimatoprost use were eye pruritus, conjunctival hyperemia, skin hyperpigmentation, ocular irritation, dry eye symptoms, and erythema of the eyelid, all occurring in fewer than 4% of patients (Latisse package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2008). Conjunctival hyperemia was the only specific event reported at a significantly higher rate by subjects receiving bimatoprost (3.6%) than those receiving vehicle (0%) (P = 0.03) [22]. For comparison, in a 3-month trial of once-daily bimatoprost treatment for glaucoma or ocular hypertension (i.e., the drug was instilled as an eye drop), the incidence of treatment-related conjunctival hyperemia and eye pruritus was approximately 46 and 9%, respectively [26]. Furthermore, dermal application of bimatoprost was not associated with iridal pigmentation or clinically meaningful changes in intraocular pressure [22; Latisse package insert, Allergan, Inc., 2008]. Differences in safety profiles of bimatoprost by route of administration may be partially explained in that a single application of bimatoprost 0.03% to the upper-eyelid margin using the provided applicator delivers approximately 5% of the dose delivered for the treatment of glaucoma (Allergan, Inc., unpublished data). Moreover, when applied to the upper-eyelid margin, subsequent absorption of the active drug into ocular tissues is expected to be minimal due to the barrier function of the skin and the small surface area to which the dose is applied.

The ability of prostaglandin analogs to increase eyelash growth does not appear limited to bimatoprost. Published reports describe latanoprost and travoprost, both prostaglandin analogs used to treat ocular hypertension, as being associated with eyelash changes, including increases in length and darkness [3, 5, 13, 27–29]. Studies evaluating the clinical efficacy of bimatoprost versus latanoprost for the treatment of ocular hypertension suggest that the side effect of increased eyelash growth is more common with bimatoprost [28]. However, these results are not necessarily comparable to those when these drugs are applied to the upper-eyelid margin, which have not been evaluated in any head-to-head studies. In addition, studies in which increased eyelash growth is recorded as an adverse event typically fail to quantify the changes using objective measures.

While other prostaglandin analogs appear capable of influencing eyelash growth, these products are not FDA-approved for the treatment of hypotrichosis. Their efficacy when applied to the upper-eyelid margins has not been fully studied in clinical trials. Moreover, the safety of these drugs when applied dermally has not been fully evaluated.

OTC Cosmetic Options

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act defines cosmetics as “articles intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body or any part thereof for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance” [30]. The FDA requires cosmetics to have an ingredient declaration but cosmetic products and ingredients are not subject to FDA premarket approval [31]. A product can be considered both a drug and a cosmetic by the FDA if it has multiple uses [32].

Historically, mascara has been used to lengthen, thicken, and darken eyelashes via the use of waxes, pigments, resins, as well as talc or fibers. In the case of liquid mascara, these ingredients adhere to lashes after the product dries, resulting in a temporary enhancement in the appearance of a person’s eyelashes [7, 8]. A number of nonmascara OTC cosmetic products are advertised to increase the length, fullness, and/or darkness of eyelashes. These products contain various ingredients such as ones described as “proprietary peptides” [33], natural extracts [34, 35], vitamins [33], and prostaglandin analogs. Some of the products that contain possible prostaglandin analogs include MD Lash Factor [36], Revitalash [37], LiLash [38], neuLash [39], Lashes to Die For [40], and RapidLash [41, 42].

As cosmetics, the efficacy of the above OTC products has not been critically evaluated and their safety has not been fully studied. Most are applied to the skin of the upper-eyelid margin and the mechanisms by which they may affect eyelash growth are largely unknown and unproven. These products also vary in the quality and comprehensiveness of patient/consumer education regarding proper use of the cosmetic.

In addition to the possibility of ingredient-specific safety concerns, mascara and other cosmetic eyelash enhancers carry a risk of bacterial and fungal contamination and subsequent infection in addition to a risk of conjunctival pigmentation [7]. Unlike prescription products, cosmetics do not benefit from a comprehensive pharmacovigilance program to detect any safety concerns that become evident with increased clinical use.

Conclusions

It is clear that eyelashes play an important role in determining beauty, and as such, prominent eyelashes are a highly sought-after attribute. Numerous options may improve the appearance of eyelashes, including mascara, artificial eyelashes, eyelash transplantation, and prostaglandin analogs. Prostaglandin analogs appear capable of influencing eyelash growth and are contained in several OTC cosmetics. Eyelash growth has also been associated with several prescription prostaglandin analogs used to treat glaucoma and ocular hypertension. The FDA has recently approved bimatoprost as the first and only option for the treatment of hypotrichosis of eyelashes [12]. In a vehicle-controlled trial, bimatoprost resulted in increased prominence, length, thickness, and darkness of patients’ natural eyelashes as assessed by clinician ratings and digital image analysis [27]. As an ocular antihypertensive agent, bimatoprost has a proven history of safety, and when applied dermally it was safe and well tolerated with a low incidence of adverse events.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

The author is a consultant and investigator for Allergan, Inc.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Synnott A. The beauty mystique. Facial Plast Surg. 2006;22:163–174. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-950173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCurdy JA., Jr Beautiful eyes: characteristics and application to aesthetic surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2006;22:204–214. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-950179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaikh MY, Bodla AA. Hypertrichosis of the eyelashes from prostaglandin analog use: a blessing or a bother to the patient? [letter] J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2006;22:76–77. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.22.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeMello M. Facial hair. In: DeMello M, editor. Encyclopedia of body adornment. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2007. p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holló G. The side effects of the prostaglandin analogues. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:45–52. doi: 10.1517/14740338.6.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batchelor D. Hair and cancer chemotherapy: consequences and nursing care—a literature study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001;10:147–163. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Draelos ZD. Special considerations in eye cosmetics. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:424–430. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(01)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Donoghue MN. Eye cosmetics. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:633–639. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8635(05)70214-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straub PM. Replacing facial hair. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24:446–452. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1102907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randall VA. Hormonal regulation of hair follicles exhibits a biological paradox. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:274–285. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moses RA. The eyelids. In: Moses RA, editor. Adler’s physiology of the eye: clinical application. 5. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby; 1970. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khong JJ, Casson RJ, Huilgol SC, Selva D. Madarosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51:550–560. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnstone MA, Albert DM. Prostaglandin-induced hair growth. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:S185–S202. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(02)00307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randall VA. Androgens and hair growth. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:314–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habif TP. Hair diseases. In: Habif TP, editor. Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and treatment. 4. St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elder MJ. Anatomy and physiology of eyelash follicles: relevance to lash ablation procedures. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;13:21–25. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Na JI, Kwon OS, Kim BJ, Park WS, Oh JK, Kim KH, Cho KH, Eun HC. Ethnic characteristics of eyelashes: a comparative analysis in Asian and Caucasian females. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1170–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso L, Fuchs E. The hair cycle. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:391–393. doi: 10.1242/jcs02793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxwell A (2009) Eyes open wide with these lash extensions. http://www.usatoday.com/life/lifestyle/2006-03-27-eyelashes_x.htm. Accessed 21 June 2009

- 20.Hernández-Zendejas G, Guerrerosantos J. Eyelash reconstruction and aesthetic augmentation with strip composite sideburn graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1978–1980. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199806000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higginbotham EJ, Schuman JS, Goldberg I, Gross RL, VanDenburgh AM, Chen K, Whitcup SM, for the Bimatoprost Study Groups 1, 2 One-year, randomized study comparing bimatoprost and timolol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1286–1293. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith S, Fagien S, Somogyi C, Whitcup SM, Beddingfield FC, Eyelash growth in subjects treated with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03%; a multicenter, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel study. In: Poster presented at American Academy of Dermatology’s 67th Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, 6-9 Mar 2009, unpublished data

- 23.Kapur R, Osmanovic S, Toyran S, Edward DP. Bimatoprost-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation: histopathological study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1541–1546. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.11.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams RD, Cohen JS, Gross RL, Liu C-C, Safyan E, Batoosingh AL, for the Bimatoprost Study Group Long-term efficacy and safety of bimatoprost for intraocular pressure lowering in glaucoma and ocular hypertension: year 4. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1387–1392. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.128454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stjernschantz JW, Albert DM, Hu D-N, Drago F, Wistrand PJ. Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:162S–175S. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(02)00292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt JD, VanDenburgh AM, Chen K, Whitcup SM, for the Bimatoprost Study Group Comparison of once- or twice-daily bimatoprost with twice-daily timolol in patients with elevated IOP: a 3-month clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00584-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mansberger SL, Cioffi GA. Eyelash formation secondary to latanoprost treatment in a patient with alopecia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:718–719. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisenberg DL, Toris CB, Camras CB. Bimatoprost and travoprost: a review of recent studies of two new glaucoma drugs. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):S105–S115. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(02)00327-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alm A, Grierson I, Shields MB. Side effects associated with prostaglandin analog therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(suppl 1):S93–S105. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Food and Drug Administration Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 USC 301. http://www.fda.gov/opacom/laws/fdcact/fdcact1.htm. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 31.US Food and Drug Administration Authority Over Cosmetics. http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/cos-206.html. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 32.US Food and Drug Administration, Is it a cosmetic, a drug, or both? (or is it soap?). http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/cos-218.html. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 33.Marini Lash Eyelash Conditioner. http://www.myjanmarini.com/product_Marini+Lash%99+Eyelash+Conditioner_17739.htm. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 34.Actifirm ActiLash. http://shop.actifirm.com/products/actifirm-actilash. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 35.DermaQuest Skin Therapy’s Eyelash Product is Drug-Free. http://www.dermaquestinc.com/files/dermalash_Response.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 36.Choy I, Lin S. Eyelash enhancement properties of topical dechloro ethylcloprostenolamide. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10:110–113. doi: 10.1080/14764170802054138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.RevitaLash Eyelash Conditioner Answers to Frequently Asked Questions. http://www.revitalash.com/faq.php. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 38.Popular LiBrow Questions. http://www.lilash.com/librow_faq.html. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 39.Pitman S (2009) Eyelash conditioner launched with cell boosting properties. http://www.cosmeticsdesign.com/Products-Markets/Eyelash-conditioner-launched-with-cell-boosting-properties. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 40.Roth PT (2009) Lashes to die for ingredients. https://ordway.com/ordway12-15/ptr/pop_ingredients.asp?prod=513. Accessed 20 Jan 2009

- 41.RapidLash Eyelash Renewal Serum. http://www.skinstore.com/p-8983-rapidlash-eyelash-renewal-serum.aspx. Accessed 17 June 2009

- 42.How Effective is RapidLash? http://www.thebeaurtydivas.com/eyelash-enhancers/rapidlash.html. Accessed 17 June 2009