Abstract

Childhood adrenocortical tumor (ACT), a very rare malignancy, has an annual worldwide incidence of about 0.3 per million children younger than 15 years. The association between inherited germline mutations of the TP53 gene and an increased predisposition to ACT was described in the context of the Li-Fraumeni syndrome. In fact, about two-thirds of children with ACT have a TP53 mutation. However, less than 10% of pediatric ACT cases occur in Li-Fraumeni syndrome, suggesting that inherited low-penetrance TP53 mutations play an important role in pediatric adrenal cortex tumorigenesis. We identified a novel inherited germline TP53 mutation affecting the acceptor splice site at intron 10 in a child with an ACT and no family history of cancer. The lack of family history of cancer and previous information about the carcinogenic potential of the mutation led us to further characterize it. Bioinformatics analysis showed that the non-natural and highly hydrophobic C-terminal segment of the frame-shifted mutant p53 protein may disrupt its tumor suppressor function by causing misfolding and aggregation. Our findings highlight the clinical and genetic counseling dilemmas that arise when an inherited TP53 mutation is found in a child with ACT without relatives with Li-Fraumeni-component tumors.

Keywords: Loss of heterozygosity, Pediatric adrenocortical tumor, Splice-site mutation, TP53

Introduction

Adrenocortical tumors (ACTs) occur rarely in children and have an estimated incidence of only 0.3 per million in individuals younger than 15 years [1]. Although several diverse genetic alterations can predispose children to ACT, TP53 mutations account for most cases. Children with ACT, particularly when it is diagnosed before the child’s fifth birthday, commonly carry an inherited TP53 mutation [2]. The association between pediatric ACT and germline TP53 mutations is so strong that ACT is now considered an independent criterion to obtain TP53 genetic testing and counseling [3]. The vast majority of germline mutations that increase the predisposition to cancer occur within the DNA binding domain (DBD) and usually abrogate TP53 sequence-specific DNA-binding activity [4]. Individuals who carry these mutations have more than an 80% risk of cancer during their lifetime and are usually tested for TP53 because of a remarkable family history of cancer (Li-Fraumeni and Li-Fraumeni-like syndrome). The core component tumors in Li-Fraumeni syndrome include adrenocortical, brain, and breast tumors; soft tissue and bone sarcomas; and acute leukemia. Recently, low-penetrance TP53 mutations have been found to increase the predisposition for ACT outside of the context of Li-Fraumeni syndrome, suggesting that the adrenal cortex is particularly sensitive to TP53 inactivation. Therefore, as more low-penetrance mutations are revealed, the critical issue is to determine their clinical relevance.

Here we report a novel inherited germline TP53 mutation affecting the acceptor splice site at intron 10 in a pediatric patient with an ACT and no family history of cancer. Our findings highlight the importance of analyzing the transcripts encoded by mutant TP53 genes in tumor tissue and reinforce the role of TP53 inactivation in pediatric ACT.

Materials and methods

The patient and her parents consented to participate in the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital International Pediatric Adrenocortical Tumor Registry following the institutional review board-approved research protocol.

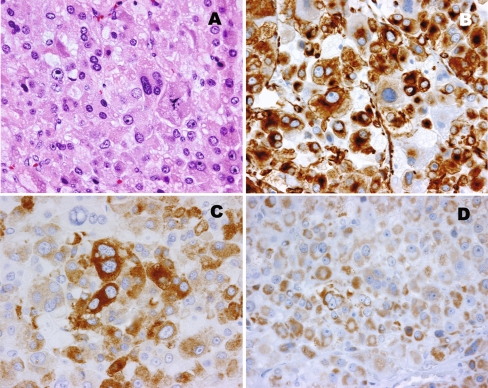

Pathologic and immunostaining analysis

This ACT was evaluated according to the following pathologic criteria: tumor size and weight, nuclear grade, mitotic rate per 50 high-power fields, tumor cell cytoplasm (0–25% and 26–100% clear) and architecture (diffuse and nondiffuse), presence or absence of atypical mitoses, necrosis, and unequivocal capsular, venous, sinusoidal, and adjacent organ invasion. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections 5 μm thick were processed for histologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Immunohistochemical sections were analyzed using the avidin–biotin complex method. Commercially available antibodies specific for vimentin, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, inhibin, melan A, pancytokeratin, Ki-67, and p53 protein were used. Immunohistochemical staining was classified as negative (no immunopositivity), weak (up to 25% of cells immunopositive), moderate (between 25 and 70% of cells immunopositive), or strong (more than 70% of cells immunopositive), and cellular localization was classified as cytoplasmic or nuclear. A rabbit or mouse (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) universal negative control was used as the negative control for each specific antibody.

Sequencing analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes and tumor samples using standard protocols. TP53 exons 2–11, including the intron sequence flanking each exon, were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and submitted to high-throughput DNA sequencing using a 3730 xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Primer sequences are available upon request, and PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C for 10 min; 35 cycles of 94, 60, and 72°C for 30 s each; and 72°C for 7 min. The sequence plots were compared to a normal sequence (National Center for Biotechnology Information, accession number NC_000017).

Reverse transcription PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from ACT tissue using a Qiagen RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen Sciences, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Reverse transcription reactions were run with 1 μg of total RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This cDNA was amplified using specific sets of primers covering exon 10 through the wild-type stop codon signal at exon 11. Other primer sets were designed to confirm the mutation and the novel stop codon signal at the 3′-untranslated region of the TP53 gene.

Protein analysis

The program JPRED3 [5] (available at www.compbio.dundee.ac.uk/www-jpred/) was used to predict the polypeptide secondary structure for wild-type p53 and the frame-shifted mutant p53.

Results

Case report

A previously healthy girl of Filipino descent, 2 years and 8 months old, had a 4-week history of rounding of her face, acne on her forehead, an increased appetite, and weight gain of 3.2 kg. Two weeks later, signs of virilization were noted. The maternal grandfather and his brother, both reported to be heavy smokers, died from lung cancer in their 50s. On admission, the patient weighed 16.7 kg (percentile, 95.7) and was 95 cm tall (percentile, 58). Her blood pressure was 142/92 on admission. She had a Cushingoid build with round moon facies and truncal obesity. No abdominal masses were palpable. She had acne on the forehead and increased oiliness of the facial skin. There was no axillary hair and no breast development. The genitalia showed signs of virilization. Laboratory tests revealed 5-dehydroepiandrosterone at 4546 ng/dL (normal, 19–42), testosterone at 84 ng/dL (normal, < 10), and cortisol at 35.1 μg/dL at 8:00 am and 32.3 μg/dL at midnight (normal, < 5). Abdominal computed tomography confirmed the finding of a 4.5 × 4.0 × 4.0 cm right adrenal mass. The mass, involving the right adrenal gland, displaced the kidney inferiorly. The mass was smoothly marginated and appeared fairly vascular with heterogeneous enhancement.

The patient underwent exploratory surgery through a right subcostal incision. The mass was removed intact without violation of its capsule. Postoperatively, her Cushingoid features resolved, and she lost 1.4 kg in 3 months despite adequate oral hydrocortisone therapy. All of her laboratory markers normalized. To date, there has been no evidence of a recurrence clinically, biochemically, or sonographically.

Histopathologic findings

The tumor weighed 48 g and measured 4.5 × 4.0 × 4.0 cm. Surgical margins were negative. No necrosis and no vascular invasion were observed. Microscopic analysis revealed the presence of multiple atypical and multipolar mitotic figures (Fig. 1, Panel A). Immunohistochemistry showed strong cytoplasmic staining for vimentin (Fig. 1, Panel B), inhibin (Fig. 1, Panel C), synaptophysin, and melan A and moderate cytoplasmic staining for p53 protein (Fig. 1, Panel D). Strong nuclear immunostaining for Ki-67 was present in 10–15% of tumor cells. Immunostaining for chromogranin A, pancytokeratin, and nuclear p53 protein was negative. Findings are consistent with typical features of ACT.

Fig. 1.

(Panel A) Cellular tumor with eosinophilic cells with prominent nuclear pleomorphism and increased mitosis. Immunohistochemistry showed the tumor cells were positive for vimentin (Panel B), inhibin A (Panel C), and cytoplasmic p53 protein (Panel D)

Identification of a germline TP53 splice-site mutation

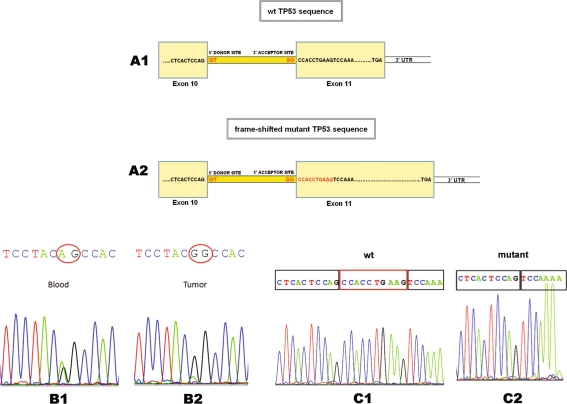

Genomic DNA from ACT tissue from this patient harbored a homozygous TP53 alteration at the junctions of intron 10 and exon 11, and the same was observed in the heterozygous state in genomic DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes, indicating a loss of heterozygosity for this locus (Fig. 2, Panels B1 and B2). This mutation was also present in genomic DNA in the heterozygous state from the patient’s mother. The father had the wild-type TP53 gene sequence. This alteration represents a change in the nucleotides AG at the splice acceptor site in intron 10 (IVS10-2 A > G), necessary for correct pre-mRNA processing, and could result in aberrant splicing. Tumor mRNA was examined for alternate splicing by reverse transcription PCR. The resulting cDNA was amplified using primers that covered exon 10 through the normal stop codon of the TP53 gene and was found to have a deletion of the initial 10 bp of exon 11 (Fig. 2, Panels C1 and C2). This 10-bp deletion causes a frame shift and predicts a new termination signal, 82 base pairs after that of the wild type. Another PCR analysis was performed using another set of primers covering exon 10 through this new stop codon, and the results showed a transcript with the corresponding size and sequence analysis confirmed the results. Because of the 10-bp deletion, frame shift, and new stop codon location, this polypeptide segment was completely different from the wild type in terms of its sequence and number of amino acid residues and resulted in a new C-terminal motif in transcripts for the mutant TP53 sequence. Schematic representations of the 3′-terminal region of the wild type and mutated TP53 gene are shown in Fig. 2, Panels A1 and A2.

Fig. 2.

Panel A1—Schematic representation of the 3′-terminal region of the wild-type TP53 gene. Panel A2—The mutation eliminates the wild-type TP53 acceptor site at the junction of intron 10 and exon 11. An internal AG acceptor site within exon 11 is selected resulting in deletion of a 10-bp sequence (ccacctgaag), a frame-shift and an alternative stop codon signal. Panel B1—Heterozygous TP53 sequence in peripheral blood lymphocyte DNA. Panel B2—Homozygous mutant TP53 sequence (loss of heterozygosity) in tumor DNA. Panel C1—cDNA of a normal individual (wild-type sequence). Panel C2—Patient’s tumor cDNA sequence (deletion of the first 10 bp of exon 11)

Splice mutation predicts an intrinsically unstructured domain for p53 protein

The C-terminal regulatory domain of TP53 is intrinsically disordered [6], has post-translational modification at numerous sites, and interacts with numerous signaling partners [7]. The amino acid composition of the mutated, frame-shifted C-terminal domain is radically different from that of the wild-type domain; therefore, this mutant domain is unlikely to regulate TP53 function in response to cellular signals. Furthermore, the sequence of the mutant C-terminal domain is inconsistent with that of normal, functional proteins (for example, 48% of the amino acids are either proline [20%], leucine [18%], or serine [10%]) and with formation of a secondary structure (α-helix or β-sheet), based on analysis using JPRED3 [5]. The unnaturally high content of proline and leucine residues may confer a propensity for the full-length, frame-shifted mutant p53 protein to misfold and aggregate. In conclusion, the non-natural and highly hydrophobic C-terminal segment of the frame-shifted mutant p53 protein may disturb tumor suppressor function by causing a loss of regulatory function, misfolding. and aggregation.

Discussion

We found a novel inherited germline TP53 acceptor splice-site mutation at the junction of intron 10 and exon 11 in a child with ACT. The loss of heterozygosity selecting against the wild-type TP53 allele in tumor tissue suggests that this mutation played a role in adrenal tumorigenesis in this case. Germline or somatic TP53 splice-site mutations have rarely been described in association with cancer [8, 9]. Furthermore, the mutation we report here has not been recorded in the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) TP53 mutation database (www.iarc.fr). Because most germline TP53 mutations registered in the IARC database are from individuals from families with cancer-prone syndromes, it is possible this TP53 splice mutation, similar to other low-penetrance TP53 mutations, is not associated with well-defined familial cancer syndromes and may not be detected until revealed in association with TP53-core tumors such as pediatric ACT. The association between low-penetrance mutations and tumorigenesis of the developmental adrenal cortex has been amply documented [10, 11], to the extent that the diagnosis of ACT alone is now considered a criterion for TP53 testing [3]. In this regard, many of the inherited germline low-penetrance TP53 mutations revealed in children with ACT [12] or choroid plexus tumors [13] may not increase carriers’ predisposition to Li-Fraumeni-component tumors. In fact, in the IARC database, only about 7.8% of cases of ACT registered have a family history of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. This contrasts with 32.2% with a family history of Li-Fraumeni syndrome when the proband has breast cancer. The finding of an inherited novel TP53 mutation in a child with ACT creates a dilemma, as this tumor can be associated with either DBD or low-penetrance mutations and therefore has substantial implications for genetic counseling.

Consistent with the interpretation that this TP53 splice mutation is of low penetrance is that the family history of cancer of this child is not typical of Li-Fraumeni syndrome [14, 15]. The mother, who is in her 30s and carries the mutation, has not been affected by cancer. Moreover only two cases of cancer have been reported in her family: her father and his brother; both heavy smokers whose cancer was diagnosed when they were in their 50s. However, the clinical-epidemiologic data of the family are limited; hence, it is plausible that the TP53 splice mutation may have tumorigenic potential similar to TP53 mutations that affect the DBD. First, the mother is still young and at risk for TP53-core-component cancers such as breast or brain tumors and soft tissue or bone sarcomas. Secondly, the familial cancer history may be incomplete, because many members of this family reside in the Philippines, and we did not have access to their medical records. Finally, lung and other cancers, although not included in the Li-Fraumeni syndrome criteria, may occur in carriers of TP53 DBD mutations. Of interest, lung cancer was the most common cancer type in carriers of germline TP53 mutations who did not develop Li-Fraumeni-component tumors [16]. Therefore, given the lack of information on the TP53 splice mutation and detailed clinical-epidemiologic data, it is not possible to determine whether the carriers of this mutation have an increased predisposition to cancer, as seen in individuals who carry TP53 mutations that disrupt the DBD of the protein.

In an attempt to further elucidate the functional characteristics of this mutation, which altered a region responsible for pre-mRNA processing, we performed transcriptome analysis. Sequencing of the TP53 transcripts obtained from RNA extracted from tumor tissue revealed that a new acceptor site was utilized, eliminating the first 10 bp of exon 11 and leading to a frame shift and an altered stop codon. The new sequence of exon 11 predicts a polypeptide different from that of the wild type in sequence and number of residues, resulting in alterations in the protein’s C-terminal region. Bioinformatics analysis of the structural features of the frame-shifted mutant p53 protein suggested that the non-natural C-terminal domain may cause misfolding and aggregation, therefore inhibiting tumor suppressor function. As noted earlier, the C-terminal domain plays a critical role in regulating TP53 function. For example, the region between residues 363 and 393 has been referred to as an apoptotic domain [17]. C-terminally deleted p53 protein has weaker apoptosis-inducing activity than intact TP53 [18]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that the ability of the isolated C-terminus to form stable tetramers in vitro is facilitated by the phosphorylation of its penultimate serine residue. Stabilization of tetramers may not only increase DNA binding but also may help to keep p53 in the nucleus by masking its nuclear export signal (NES) sequence [19]. The C-terminus of the frame-shifted mutant p53 protein reported here has a high leucine content and hydrophobic character that fits the criteria established for an intrinsic NES [20]. An intrinsic NES mediates the subcellular localization and nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of p53 through an association with an export receptor [19], consistent with cytoplasmic p53 immunostaining observed in this case. Taken together, the transcriptome analysis suggests that this mutation causes a loss of tumor suppressor function through a variety of mechanisms, perhaps to an extent similar to that associated with DBD mutations and with similar clinical-pathologic consequences.

In summary, the type of malignancy associated with this patient, her family history of cancer, TP53 genetic testing findings, and predictive analysis of the mutant protein highlight the complexity of the relationship between TP53 mutations and malignancy. Careful consideration of these factors is critical for appropriate patient management and genetic counseling.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Galloway for expert editorial review. This study was partially supported by the St. Jude International Outreach Program, by a Center of Excellence Grant from the State of Tennessee, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Adrenocortical tumor

- DBD

DNA-binding domain

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

- NES

Nuclear export signal

References

- 1.Figueiredo BC, Stratakis CA, Sandrini R, DeLacerda L, Pianovsky MA, Giatzakis C, Young HM, Haddad BR. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of adrenocortical tumors of childhood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1116–1121. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.3.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Johnson J, Bratti C, Bhatia K, Magrath IT, Fraumeni JF., Jr Elevated levels of p53 protein in adrenocortical carcinomas from Costa Rica. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:125. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)00465-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez KD, Noltner KA, Buzin CH, Gu D, Wen-Fong CY, Nguyen VQ, Han JH, Lowstuter K, Longmate J, Sommer SS, Weitzel JN. Beyond Li Fraumeni Syndrome: clinical characteristics of families with p53 germline mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1250–1256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petitjean A, Achatz MI, Borresen-Dale AL, Hainaut P, Olivier M. TP53 mutations in human cancers: functional selection and impact on cancer prognosis and outcomes. Oncogene. 2007;26:2157–2165. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole C, Barber JD, Barton GJ. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W197–W201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joerger AC, Fersht AR. Structural biology of the tumor suppressor p53. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:557–582. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.060806.091238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruse JP, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell. 2009;137:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varley JM, McGown G, Thorncroft M, White GR, Tricker KJ, Kelsey AM, Birch JM, Evans DG. A novel TP53 splicing mutation in a Li-Fraumeni syndrome family: a patient with Wilms’ tumour is not a mutation carrier. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1081–1083. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varley JM, Attwooll C, White G, McGown G, Thorncroft M, Kelsey AM, Greaves M, Boyle J, Birch JM. Characterization of germline TP53 splicing mutations and their genetic and functional analysis. Oncogene. 2001;20:2647–2654. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varley JM, McGown G, Thorncroft M, James LA, Margison GP, Forster G, Evans DG, Harris M, Kelsey AM, Birch JM. Are there low-penetrance TP53 Alleles? evidence from childhood adrenocortical tumors. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:995–1006. doi: 10.1086/302575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro RC, Sandrini F, Figueiredo B, Zambetti GP, Michalkiewicz E, Lafferty AR, DeLacerda L, Rabin M, Cadwell C, Sampaio G, Cat I, Stratakis CA, Sandrini R. An inherited p53 mutation that contributes in a tissue-specific manner to pediatric adrenal cortical carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9330–9335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161479898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueiredo BC, Sandrini R, Zambetti GP, Pereira RM, Cheng C, Liu W, Lacerda L, Pianovski MA, Michalkiewicz E, Jenkins J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Mastellaro MJ, Vianna S, Watanabe F, Sandrini F, Arram SB, Boffetta P, Ribeiro RC. Penetrance of adrenocortical tumours associated with the germline TP53 R337H mutation. J Med Genet. 2006;43:91–96. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabori U, Shlien A, Baskin B, Levitt S, Ray P, Alon N, Hawkins C, Bouffet E, Pienkowska M, Lafay-Cousin L, Gozali A, Zhukova N, Shane L, Gonzalez I, Finlay J, Malkin D (2010) TP53 alterations determine clinical subgroups and survival of patients with choroid plexus tumors. J Clin Oncol 28:1995–2001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Nelson CE, Kim DH, Kassel J, Gryka MA, Bischoff FZ, Tainsky MA, et al. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990;250:1233–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.1978757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olivier M, Goldgar DE, Sodha N, Ohgaki H, Kleihues P, Hainaut P, Eeles RA. Li-Fraumeni and related syndromes: correlation between tumor type, family structure, and TP53 genotype. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6643–6650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nichols KE, Malkin D, Garber JE, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Li FP. Germ-line p53 mutations predispose to a wide spectrum of early-onset cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang XW, Harris CC. TP53 tumour suppressor gene: clues to molecular carcinogenesis and cancer therapy. Cancer Surv. 1996;28:169–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almog N, Goldfinger N, Rotter V. p53-dependent apoptosis is regulated by a C-terminally alternatively spliced form of murine p53. Oncogene. 2000;19:3395–3403. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stommel JM, Marchenko ND, Jimenez GS, Moll UM, Hope TJ, Wahl GM. A leucine-rich nuclear export signal in the p53 tetramerization domain: regulation of subcellular localization and p53 activity by NES masking. EMBO J. 1999;18:1660–1672. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim FJ, Beeche AA, Hunter JJ, Chin DJ, Hope TJ. Characterization of the nuclear export signal of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 Rex reveals that nuclear export is mediated by position-variable hydrophobic interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5147–5155. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]