Abstract

Forty-four soybean genotypes with different photoperiod response were selected after screening of 1000 soybean accessions under artificial condition and were profiled using 40 SSR and 5 AFLP primer pairs. The average polymorphism information content (PIC) for SSR and AFLP marker systems was 0.507 and 0.120, respectively. Clustering of genotypes was done using UPGMA method for SSR and AFLP and correlation was 0.337 and 0.504, respectively. Mantel's correlation coefficients between Jaccard's similarity coefficient and the cophenetic values were fairly high in both the marker systems (SSR = 0.924; AFLP = 0.958) indicating very good fit for the clustering pattern. UPGMA based cluster analysis classified soybean genotypes into four major groups with fairly moderate bootstrap support. These major clusters corresponded with the photoperiod response and place of origin. The results indicate that the photoperiod insensitive genotypes, 11/2/1939 (EC 325097) and MACS 330 would be better choice for broadening the genetic base of soybean for this trait.

Keywords: photoperiod response, SSR, AFLP, genetic diversity, soybean

The photoperiod response is a major criterion, which determines the latitudinal adaptation of a soybean variety (Hartwig and Kiihl, 1979). A considerable variation in the relative sensitivity of soybean genotypes to differences in photoperiod has been reported (Sinclair and Hinson, 1992). Roberts et al. (1996) had also emphasized the importance of photoperiod-insensitivity in the improvement of soybean crop after characterizing soybean genotypes in conjunction with an analysis of the world-wide range of photo-thermal environments in which soybean crops are grown. Most of the Indian soybean cultivars (> 95%) were found to be highly sensitive to photoperiod that limits their cultivation in only localized area (Bhatia et al., 2003). Thus, it is important to identify genetically diverse source of photoperiod-insensitivity gene(s) to broaden the genetic base of Indian soybean cultivars.

Better knowledge of the genetic similarity of breeding materials could help to maintain genetic diversity and sustain long-term selection gains. Furthermore, monitoring the genetic variability within the gene pool of elite breeding material could make crop improvement more efficient by the directed accumulation of favored alleles thus decreasing the amount of material to be screened. Several studies have used molecular markers to help in identification of genetically diverse genotypes to use in crosses in cultivar improvement programme. These studies have more success than conventional selection programme in producing productive lines from plant introduction/exotic lines crosses with elite lines (Maughan et al., 1996; Thompson and Nelson, 1998). Among the molecular markers simple sequence repeats (SSR) are reproducible, co-dominant and distributed through out the genome. The AFLPs being dominant markers allow studying many loci simultaneously and generating highly reproducible markers that are also considered to be locus specific within a species (Maughan et al., 1996). These two markers can detect higher levels of genetic diversity in soybean and have been utilized for many purposes including genome mapping, gene tagging, estimation of genetic diversity and varietal identification (Maughan et al., 1995, 1996; Powell et al., 1996; Cregan et al., 1999; Brown-Guedira et al., 2000; Narvel et al., 2000; Ude et al., 2003; Wange et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2008). However, no information is available on assessment of genetic diversity in response to photoperiodism in soybean. The present study was conducted to identify genetic diversity in the soybean gene pool for photoperiod insensitivity using SSR and AFLP markers.

One thousand soybean genotypes obtained from India, USA, Hungary, Philippines and Taiwan were screened for sensitivity to photoperiodism as described by Singh et al. (2008). Out of these 44 genotypes, 15 genotypes showing different degree of photoperiod insensitivity and 29 sensitive genotypes were selected for analysis using SSR and AFLP markers. The place of origin, EC number and their response to photoperiodism are given in Table 1. Ten leaves, one each from ten plants of 44 soybean genotypes were collected and DNA was isolated by the method described by Doyle and Doyle (1990).

Table 1.

Genotypes and cultivars, country of origin and classification regarding sensitivity to photoperiodism of the 44 soybean genotypes/cultivars used in this study.

| S. no. | Collection Id. | Variety or original identity | Country of origin of germplasm collection | Classification* |

| 1 | MACS 330 | Cultivar | India | I |

| 2 | EC 325097 | 11/2/1939 | Hungary | I |

| 3 | EC 333897 | Maple Arrow | USA | I |

| 4 | EC 34101 | Dun-NunII-2-15 | Hungary | I |

| 5 | EC 325118 | 1158/84 | Hungary | I |

| 6 | EC 325100 | 1145/84 | Hungary | LS |

| 7 | LSb 1 | Cultivar | India | LS |

| 8 | EC 333922 | PI 437418 | USA | LS |

| 9 | EC 325106 | 1146/84 | Hungary | MS |

| 10 | EC 251402 | S-100 | China | MS |

| 11 | EC 333912 | PI 424-489A | USA | MS |

| 12 | EC 325114 | 2426/85 | Hungary | MS |

| 13 | EC 333920 | LAKOTA | USA | MS |

| 14 | EC 232075 | ROMEA | Philippines | MS |

| 15 | EC 333880 | Evans | USA | MS |

| 16 | EC 325159 | 111-3-250 | Hungry | HS |

| 17 | EC 325115 | 1172/84 | Hungary | HS |

| 18 | EC 333925 | PI 437428A | USA | HS |

| 19 | EC 325117 | 1165/84 | Hungary | HS |

| 20 | EC 333867 | Harosoy | USA | HS |

| 21 | EC 333919 | Hedgson | USA | HS |

| 22 | AGS 16 | - | Taiwan | HS |

| 23 | EC 175321 | G-1594 | Taiwan | HS |

| 24 | EC 242091 | 30229-11-11 | Philippines | HS |

| 25 | EC 358004 | PI 437833 | USA | HS |

| 26 | EC 251770 | Pershing | USA | HS |

| 27 | Samarat | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 28 | EC 103336 | CES-434 | Philippines | HS |

| 29 | EC 291448 | PI 90-763 | USA | HS |

| 30 | EC 378783 | - | USA | HS |

| 31 | EC 333904 | PI 404-177 | USA | HS |

| 32 | EC 251446 | Jackson | USA | HS |

| 33 | Type 49 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 34 | Hardee | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 35 | Co1 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 36 | JS80-21 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 37 | GS1 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 38 | NRC 37 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 39 | PK 472 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 40 | MAUS 32 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 41 | Indirasoya-9 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 42 | MACS 58 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 43 | MACS124 | Cultivar | India | HS |

| 44 | MACS13 | Cultivar | India | HS |

*I = Photoperiod insensitive; LS = Low sensitivity; MS = moderate sensitivity; HS = high sensitivity.

Simple sequence repeat (SSR)/ microsatellite analysis was carried out using 40 mapped markers distributed on all the 20 chromosomes (Cregan et al., 1999) (Table 2). Amplification was carried out in a 10 μL reaction mixture consisting of 1X PCR assay buffer (Bangalore Genei Pvt. Ltd., India), 200 μM of the four dNTPs (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania, USA), 12 ng (1.8 picomole) each of forward and reverse primers (Life Technologies, USA), 0.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Bangalore Genei Pvt. Ltd., India) and 25 ng template DNA. PCR reactions were carried out in a thermal cycler (Gene Amp 9600 model, version 2.01 from Perkin Elmer, USA) using the following cycling parameters: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 2 min and finally a primer extension cycle of 7 min at 72 °C. The amplification products were separated on 3% metaphor agarose gels containing 1.5% gel star (FMC Bio Products, Rockland, USA). Gels were run for 3 h at 50 V in 1X TBE buffer. DNA fragments were visualized under UV light and photographed using a Polaroid photographic system. The size of the fragments was estimated using a 50-bp DNA ladder (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania).

Table 2.

SSR loci, linkage group with position, allele number and polymorphism information content (PIC) for 44 soybean genotypes/cultivars.

| SSR primer pair | Primer name | Linkage group | cM position | No. of alleles | PIC |

| 1 | Satt276 | A1 | 5.70 | 3 | 0.613 |

| 2 | Satt211 | A1 | 95.96 | 3 | 0.369 |

| 3 | Satt493 | A2 | 35.02 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | Satt233 | A2 | 100.09 | 3 | 0.520 |

| 5 | Satt415 | B1 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.616 |

| 6 | Satt063 | B 2 | 93.49 | 4 | 0.584 |

| 7 | Satt126 | B2 | 27.63 | 3 | 0.644 |

| 8 | Satt194 | C1 | 26.35 | 2 | 0.118 |

| 9 | Satt524 | C1 | 120.12 | 1 | 0 |

| 10 | Satt170 | C2 | 70.56 | 2 | 0.080 |

| 11 | Satt460 | C2 | 117.77 | 4 | 0.575 |

| 12 | Satt184 | Dla | 17.52 | 3 | 0.581 |

| 13 | Satt129 | Dla | 109.67 | 2 | 0.384 |

| 14 | Satt216 | D1b | 9.80 | 4 | 0.728 |

| 15 | Satt459 | D1b | 118.6 | 3 | 0.224 |

| 16 | Satt498 | D2 | 32.14 | 2 | 0.118 |

| 17 | Sat_114 | D2 | 84.18 | 2 | 0.249 |

| 18 | Satt231 | E | 70.23 | 3 | 0.503 |

| 19 | Satt411 | E | 12.92 | 6 | 0.703 |

| 20 | SOYHSP176 | F | 68.44 | 4 | 0.718 |

| 21 | Satt072 | F | 87.01 | 1 | 0 |

| 22 | Satt038 | G | 1.84 | 5 | 0.772 |

| 23 | Sct_ 187 | G | 107.11 | 3 | 0.249 |

| 24 | Sat_127 | H | 28.80 | 4 | 0.653 |

| 25 | Satt434 | H | 105.74 | 4 | 0.663 |

| 26 | Satt587 | I | 31.49 | 1 | 0 |

| 27 | Satt354 | I | 46.22 | 6 | 0.796 |

| 28 | Satt431 | J | 78.57 | 4 | 0.684 |

| 29 | Sct_046 | J | 24.09 | 1 | 0 |

| 30 | Satt539 | K | 1.80 | 2 | 0.041 |

| 31 | SOYPRP1 | K | 46.94 | 5 | 0.752 |

| 32 | Satt388 | L | 23.55 | 1 | 0 |

| 33 | Satt278 | L | 31.22 | 4 | 0.639 |

| 34 | Sat_099 | L | 78.23 | 4 | 0.609 |

| 35 | GMSC514 | M | 3.05 | 3 | 0.292 |

| 36 | Satt346 | M | 112.79 | 3 | 0.642 |

| 37 | Sat_084 | N | 36.86 | 2 | 0.353 |

| 38 | GMABAB | N | 73.10 | 4 | 0.749 |

| 39 | Sat_132 | O | 8.75 | 4 | 0.352 |

| 40 | Sat_109 | O | 127.50 | 5 | 0.674 |

AFLP fingerprints were generated based on the protocol of Zabeau and Vos (1993) with the AFLP Analysis System II (Invitrogen Corporation, Grand Island, NY) following the manufacturer's instructions. The size of the fragments was estimated using a 20-bp DNA ladder (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania).

The scoring of bands was done as present (1) or absent (0) for each AFLP and SSR marker allele and data was entered in a binary data matrix as discrete variables. Jaccard's coefficient of similarity was calculated and a dendrogram was constructed by using Unweighted Pair Group Method of Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA). The computer package NTSYS-PC Version 2.02 (Rohlf, 1998) was used for cluster analysis. The same software was used to perform the Mantel test of correlation between the cophenetic values and the Jaccard similarity coefficients to ascertain reliability of the obtained clusters. Robustness of the clustering pattern was also tested using bootstrap analysis using Free Tree - Free ware software (Pavlicek et al., 1999). The polymorphism information content (PIC) was calculated for SSR marker as 1 - Σ pij2 where pij is the frequency of the jth allele of ith marker (Weir, 1990) while PIC for AFLP marker was calculated as described by Powell et al. (1996).

Among the 40 SSR primer pairs used in the present study, 34 (85.0%) were polymorphic, while six primers revealed monomorphic patterns. In total, 120 alleles were detected for the 34 polymorphic SSR primers, with an average of 3.53 alleles per locus. Allele sizes ranged from 90 bp to 300 bp. Summarized data for the SSR loci and their PIC values are presented in Table 2. The PIC value, a reflection of allelic diversity and frequency among the soybean genotypes analyzed were generally high for all the SSR loci tested. PIC values ranged from 0.041 to 0.796, with an average of 0.507. Seven SSR loci revealed PIC values higher than 0.70. Among these, Satt354 and Satt038 are noteworthy due to their relatively high polymorphism (six and five alleles each, respectively), and high PIC values (0.796 and 0.772), respectively. The polymorphism of SSR loci detected in this study was consistent with data obtained in some previous studies (Doldi et al., 1997; Brown-Guedira et al., 2000; Narvel et al., 2000), but was lower than that reported by others (Rongwen et al., 1995; Diwan and Cregan, 1997). The PIC values of our study were in agreement with the data of Doldi et al. (1997) and Brown-Guedira et al. (2000), who detected mean gene diversity values of 0.50 and 0.69 in a group of 39 and 36 elite/commercial soybean cultivars, respectively.

The five AFLP primer combinations used in this study were selected on the basis of a high number of scorable polymorphic bands. It was possible to discriminate each one of the 44 soybean genotypes using five primer combinations. Band sizes ranged from 100 to 700 bp. The five primer pairs revealed a total of 449 different bands that were of sufficient intensity to be scored, and 208 (46.3%) of these were polymorphic. The percentage of polymorphic bands per assay unit ranged from 34.0% (E-ACT/M-CAT) to 57% (E-AAG/M-CTT), with an average of 46.3%. The average PIC score for AFLP primer combination was 0.12, with a range of 0.08 to 0.16 (Table 3). A similar average PIC score for AFLP was also reported in an earlier study on soybean (Ude et al., 2003). 91 polymorphic bands showed PIC scores > 0.30 indicating that only 20.3% of the 449 bands contributed significantly to the genetic variation of the soybean genotypes. A PIC score > 0.30 has been described previously in soybean based on RFLP (Keim et al., 1992; Lorenzen et al., 1995), RAPD (Thompson and Nelson, 1998) and AFLP (Ude et al., 2003) results and shows its usefulness in other soybean germplasm diversity studies. Thus, the polymorphism seen by SSR and AFLP efficiently distinguished all these accessions of soybean genotypes.

Table 3.

Total number of bands, proportion of polymorphic bands and polymorphism information content (PIC) for each AFLP primer pair used in the analysis of 44 soybean lines.

| Primer pair | Total no. of bands | Proportion of polymorphic bands | PIC |

| E-ACC/M-CAA | 89 | 0.55 | 0.15 |

| E-AAG/M-CTT | 101 | 0.57 | 0.16 |

| E-ACC/M-CAC | 75 | 0.47 | 0.12 |

| E-ACA/M-CAC | 86 | 0.43 | 0.08 |

| E-ACT/M-CAT | 98 | 0.34 | 0.097 |

The similarity coefficients based on shared SSR and AFLP bands revealed that the average genetic similarity (GS) between genotypes was 0.446, with a range of 0.220 to 0.765. GS estimates for AFLP and SSR were 0.504 and 0.337, respectively. As expected, the level of polymorphism was higher for SSR (0.507) than for AFLP (0.12), reflecting the hypervariability of SSR markers. SSR/microsatellite analysis thus revealed significantly lower mean genetic similarity values (0.337) than AFLP (0.504). Similar results have been reported for soybean (Powell et al., 1996) and olive (Bandelj et al., 2003). Dendrograms were constructed from genetic similarity data, and clusters were tested for associations. Cophenetic coefficients were fairly high in both molecular systems (SSR = 0.924 and AFLP = 0.958) indicating a good fit for clustering. The Mantel correlation test was used to compare between SSR and AFLP, as well as the combined data. The cophenetic matrix values and the estimated correlations for the two molecular systems and with combination were r = 0.604 (SSR vs. AFLP), r = 0.771 (SSR vs. combination) and 0.971 (AFLP vs. combination), respectively. All these were statistically significant. The slightly lower level of correlation between SSR and AFLP in the present study could probably reflect that these markers are known to target different genomic fractions involving repeat and/or unique sequences, which may have differentially evolved or been preserved during the course of natural or artificial selection.

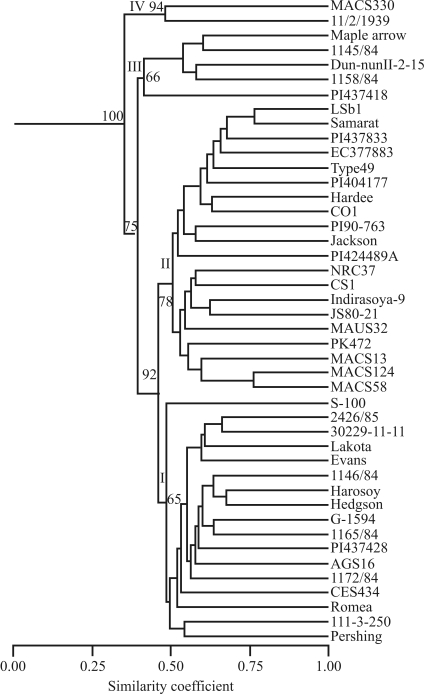

Cluster analysis based on coefficient of similarity classified the soybean genotypes into four major clusters, which were designated as I, II, III and IV in this study (Figure 1). The dendrogram indicated that 82% of the 44 soybean genotypes clustered in the range of 0.55 to 0.76 similarity coefficients. A correspondence between photoperiodism and place of origin of the cultivars was evident from Figure 1. The Mantel test indicated good fit for the clustering pattern with fairly moderate bootstrap supports (65%-100%). The cluster ‘I' was composed of six genotypes from USA, five from Hungary, three from Philippines, two from Taiwan and one from China, however S-100 appeared as an outlier in this group (Figure 1). Flowering in this group was delayed from 12-68 days in extended photoperiod. Grouping of soybean ancestors/cultivars ftom the USA with Hungarian, French and Japanese genotypes was also reported (Brown-Guedira et al., 2000). The grouping of Jackson, S-100, Evans and Pershing in different subclusters in the present study is in the agreement with previous results (Ude et al., 2003). Cluster II mainly consisted of Indian soybean cultivars (14 cultivars) along with six genotypes from the USA and was again divided into subclusters. The genotypes of this group did not flower under extended photoperiods and are highly photoperiod-sensitive, except for LSb1 and PI424-489A, which flowered after 7 and 14 days under extended photoperiod, respectively. Grouping of six genotypes/cultivars from the USA along with Indian soybean cultivars in II-a is obvious, as most of the initial Indian soybean varieties are either direct introductions from theUSA or were selected or bred using introductions as one of the parent (Karmakar and Bhatnagar, 1996). The genotypes of subgroup II - b comprised only Indian soybean cultivars and clustered together with 53% similarity. The Indian soybean cultivars shown to cluster in this study mainly came from the central and southern zones of India, and the result is in agreement with an earlier report (Hymowitz and Kaizuma, 1981).

Figure 1.

Dendrogram of 44 soybean lines produced by the UPGMA clustering method based on a genetic similarity matrix derived from 120 SSR and 449 AFLP markers. Bootstrap values in percentages for the four major clusters are mentioned at the respective nodes. The major clusters are indicated as I, II, III and IV node on the left side.

Cluster III consisted of four genotypes (three from Hungary (1145/84, Dun NunII-2-15, 1158/84) and one from the USA (Maple Arrow), which grouped together with 0.545 similarities. Though genotype PI 437418 did not group with cluster III, it showed a reasonable level of similarity with this cluster and, thus can be considered as an outlier of this group. The genotypes of this group showed delayed flowering from 1-5 days in extended photoperiod. Cluster IV included one genotype each from Hungary and India. This cluster consisted of diverse genotypes (MACS330, a cross from Monetta (USA) X EC95937 (USSR), and 11/2/1939, a line from Hungary) which showed no delay in flowering under extended photoperiod. The cluster formed by these two genotypes is not strong and showed only 0.50 similarity between each of its members, which, in turn, showed 0.36 similarity with other genotypes of the present study. It is evident from dendrogram (Figure 1) that soybean cultivars/genotypes from the USA grouped along with genotypes of different origin in different clusters, the reason being that a large number of the accessions in the USDA soybean collection are from the same regions of China and Korea. These introductions that make up the base of the American germplasm (Brown-Guedira et al., 2000) were used for development of soybean cultivars in the USA.

Soybean producing regions in India range from the lower Himalayan Hills and Northern Plain in the north to the Deccan Plateau in the south. The soybean varieties cultivated in these areas were developed through separate breeding programs, because most of the Indian soybean varieties are photoperiod sensitive, restricting their cultivation to localized areas only. The genotypes, 11/2/1939 (Hungary) and MACS330 (India) identified as photoperiod insensitive in the present study formed a separate group, as clearly shown by UPGMA (Figure 1). Literature reports indicate that there is a relationship between marker diversity of parents and genetic variance of the resulting progeny. Collecting data on genetic diversity in parents and progeny, however, is time consuming and expensive (Maughan et al., 1996). Thus, identifying genetically diverse parents based for desirable trait based on molecular markers would be a good approach for the production of desirable progeny. This approach has been already used for production of high yielding progeny in soybean (Thompson and Nelson, 1998). In the present study, we are making available potential germplasm resources for photoperiod insensitivity to soybean breeders that can be used for introgression of photoperiod insensitivity genes into soybean cultivars for wider adaptability.

Acknowledgments

R.K. Singh is grateful to the National Agricultural Technology Project (Team of Excellence), Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Government of India for the fellowship. The authors thank the Director of NRC for Soybean Indore for facilities and support provided.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Everaldo Gonçalves de Barros

References

- Bandelj D., Jakse J., Javornik B. Assessment of genetic variability of olive varieties by microsatellite and AFLP markers. Euphytica. 2003;136:93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V.S., Yadav S., Rashmi A., Lakshami N., Guruprasad K.N. Assessment of photoperiod sensitivity for flowering in Indian soybean varieties. Ind J Plant Physiol. 2003;8:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Guedira G.L., Thompson J.A., Nelson R.L., Warburton M.L. Evaluation of genetic diversity of soybean introductions and North American ancestors using RAPD and SSR markers. Crop Sci. 2000;40:815–823. [Google Scholar]

- Cregan P.B., Jarvik T., Bush A.L., Shoemaker R.C., Lark K.G., Kahler A.L., Kaya N., VanToai T.T., Lohnes D.G., Chung J., et al. An integrated genetic linkage map of the soybean. Crop Sci. 1999;39:1464–1490. [Google Scholar]

- Diwan N., Cregan P.B. Automated sizing of fluorescent-labeled simple sequence repeat markers to assay genetic variation in soybean. Theor Appl Genet. 1997;95:723–733. [Google Scholar]

- Doldi M.L., Vollmann J., Lelley T. Genetic diversity in soybean as determined by RAPD and microsatellite analysis. Plant Breed. 1997;116:331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J.J., Doyle J.L. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig E.E., Kiihl R.A.S. Identification and utilization of a delayed flowering character in soybeans for short day conditions. Field Crop Res. 1979;2:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hymowitz T., Kaizuma N. Soybean seed protein electrophoresis profiles from 15 Asian countries or regions: Hypotheses on paths of dissemination of soybeans from China. Econ Bot. 1981;35:10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar P.G., Bhatnagar P.S. Genetic improvement of soybean varieties released in India from 1969 to 1993. Euphytica. 1996;90:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Keim P., Beavis W., Schupp J., Freestone R. Evaluation of soybean RFLP marker diversity in adapted germplasm. Theor Appl Genet. 1992;85:205–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00222861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen L.L., Boutin S., Young N., Specht J.E., Shoemaker R.C. Soybean pedigree analysis using map- based markers: I. Tracking RFLP markers in cultivars. Crop Sci. 1995;35:1326–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan P.J., Saghai Maroof M.A., Buss G.R. Microsatellite and amplified sequence length polymorphism in cultivated and wild soybean. Genome. 1995;38:715–725. doi: 10.1139/g95-090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan P.J., Saghai Maroof M.A., Buss G.R., Huestis G.M. Amplified fragment length polymorphism in soybean: Species diversity, inheritance and near isogenic line analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 1996;93:392–401. doi: 10.1007/BF00223181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narvel J.M., Fehr W.R., Chu W., Grant D., Shoemaker R.C. Simple sequence repeats diversity among soybean plant introduction and elite genotypes. Crop Sci. 2000;40:1452–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlicek A., Hrda S., Flegr J. Free Tree - Freeware program for construction of phylogenetic trees on the basis of distance data and bootstrap/jackknife analysis of the tree robustness. Application in the RAPD analysis of the genus Frenkelia. Folia Biol. 1999;45:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell W., Morgante M., Andre C., Hanafey M., Vogel J., Tingey S., Rafalski A. The comparison of RFLP, RAPD, AFLP and SSR markers for germplasm analysis. Mol Breed. 1996;2:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E.H., Qi A., Ellis R.H., Summerfield R.J., Lawn R.J., Shanmugasundaram S. Use of field observations to characterize genotypic flowering responses to photoperiod and temperature: A soybean exemplar. Theor Appl Genet. 1996;93:519–533. doi: 10.1007/BF00417943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf F.J. NTSYS-PC Numerical Taxonomy and Multivariate Analysis system. New York: Exeter Software; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rongwen J., Akkaya M.S., Lavi U., Cregan P.B. The use of microsatellite DNA markers for soybean genotype identification. Theor Appl Genet. 1995;19:43–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00220994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair T.R., Hinson K. Soybean flowering in response to the long juvenile trait. Crop Sci. 1992;32:1242–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.K., Bhat K.V., Bhatia V.S., Mohapatra T., Singh N.K. Association mapping for photoperiod insensitivity trait in soybean. Natl Acad Sci Lett. 2008;31:281–283. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.A., Nelson R.L. Utilization of diverse germplasm for soybean yield improvement. Crop Sci. 1998;38:1362–1368. [Google Scholar]

- Ude G.N., Kenworthy W.J., Costa J.M., Cregan P.B., Alvernaz J. Genetic diversity of soybean cultivars from China, Japan, North America and North American ancestral lines determined by Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism. Crop Sci. 2003;43:1858–1867. [Google Scholar]

- Wange L., Guan R., Zhangxiong L., Chang R., Qui L. Genetic diversity of Chinese cultivated soybean as revealed by SSR markers. Crop Sci. 2006;46:1032–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Weir B. Genetic Data Analysis: Methods for Desecrate Population Genetic Data. Sunderland: Sinauor Assoc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zabeau M., Vos P. Selective restriction fragment amplification: A general method for DNA fingerprinting. European Patent Application number 92402629.7. Publication number 0. 1993;534858:A1. [Google Scholar]