Abstract

Background

Guidelines are one of the means by which health care organizations try to improve health care and lower its cost. Studies have shown, however, that guidelines are still not being adequately implemented. In this exploratory study, we examine the link between physicians’ knowledge of and compliance with guidelines: specifically, guidelines for the treatment of three cardiovascular diseases (arterial hypertension, heart failure and chronic coronary heart disease [CHD]) in primary care.

Methods

We assessed primary care physicians’ knowledge of the guidelines with a representative postal survey, using a questionnaire about the treatment of cardiovascular diseases (2500 questionnaires sent). We assessed the responding physicians’ compliance with the guidelines by analyzing patient data from a sample of 30 of them for various indicators of compliance. Of these 30 physicians, 15 met our operational criteria for adequate knowledge of the guidelines, and 15 did not.

Results

437 (40%) of the physicians knew the guidelines adequately. Physicians answered questions about chronic CHD in accordance with the guidelines more often than they did questions about arterial hypertension (74% versus 11%). Our exploratory analysis of guideline compliance revealed that physicians who knew the guidelines adequately performed no differently than physicians who did not with respect to 12 of the 16 compliance indicators. As for the remaining 4 compliance indicators, it turned out, surprisingly, that physicians who did not know the guidelines adequately performed significantly better than those who did.

Conclusion

These preliminary findings imply that physicians’ knowledge of guidelines does not in itself lead to better guideline implementation. Further studies are needed to address this important issue.

The introduction of guidelines for medical care is one of many strategies adopted by various health care organizations to deal with quality-related and economic deficits in health care provision. To date, however, the goal—patient care conforming to guidelines—has not been attained. Numerous national and international studies have shown that guidelines are still not being adequately implemented in practice (1– 3), despite physicians’ proven acceptance of guideline-oriented, evidence-based medicine (4– 8).

With regard to cardiovascular diseases, investigations show a wide variation in physicians’ knowledge of the recommendations embodied in guidelines (9– 11). The German follow-up of the Hypertension Evaluation Project clearly demonstrated inadequate knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension (9, 12). There is also evidence of deficiencies in treatment quality that appear to be due, among other factors, to inadequate implementation of existing cardiological treatment recommendations (13– 15).

The translation of guideline recommendations into concrete medical practice is a complex process in which physician-related, patient-related, guideline-related, and educative factors all play a role (16, 17). Little research has yet been conducted to ascertain the extent to which knowledge of prevailing guidelines for diagnosis and treatment affects how physicians manage their patients (18).

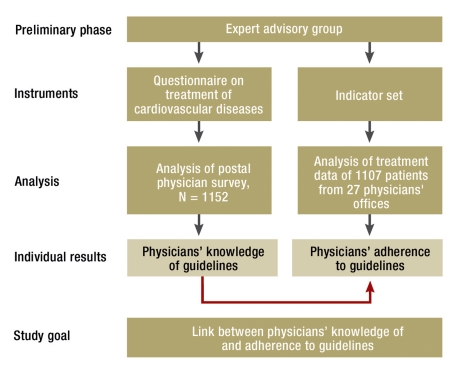

The aim of this exploratory study was to investigate the link between physicians’ knowledge of and compliance with guidelines in the primary care of three cardiovascular diseases—arterial hypertension, heart failure, and chronic coronary heart disease (CHD). Primary care physicians’ knowledge of guidelines was assessed by means of a representative postal survey. In a group of 30 responders we evaluated adherence to guidelines on the basis of data from patients’ records (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design and procedure

Methods

Assessment of physicians’ knowledge of guidelines

We cooperated with an interdisciplinary expert advisory group to develop a questionnaire to assess primary care physicians’ knowledge of guidelines on the basis of the existing published recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of the three selected diseases (e1– e6). (Following publication of Guideline No. 9 on heart failure by the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians [DEGAM] in 2006 and Version 1.5 of the German National Disease Management Guidelines on CHD in 2007, the questionnaire was inspected for discrepancies. None were revealed.)

The questionnaire on treatment of cardiovascular diseases contained a total of 15 multiple-choice questions, five on each of the three diseases. The questions were primarily patient-oriented and related to the primary care physicians’ treatment strategies. Only one of the possible answers to each question corresponded to the guidelines’ recommendations.

The scoring system for analysis of the responses comprised a quantitative aspect (number of answers complying with the guidelines) and a qualitative aspect (three cardinal questions). A physician was judged to know the guidelines adequately if his/her answers to 10 of the 15 questions, including three questions identified as particularly important by the expert advisory group, corresponded to the guidelines.

After preliminary testing, the questionnaire was sent to 1250 members of the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (ASHIP) in each of two parts of Germany, the region of North Rhine and the state of Saxony. These physicians were randomly selected from the registers of the two associations. The data were pseudonymized in accordance with the regulations on data protection, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne.

The data were statistically analyzed with the aid of the program SPSS 18.0. Relative and absolute frequencies were calculated and a logistical regression model was computed. A detailed account of the methods used can be found online (eSupplement).

E-Supplement.

Supplementary description of methods

This supplementary text gives details of individual steps in the representative survey of physicians’ knowledge of guidelines (development of the questionnaire, development of a scoring system) and in the exploratory investigation of physicians’ compliance with guidelines (recruitment of participating physicians, patient data acquisition). In both cases an interdisciplinary group of experts provided advice on methodology. Moreover, the indicator-guided comparison of extreme groups is described.

Expert advisory group

An interdisciplinary expert advisory group supported the research team in developing the survey instruments. The group was tasked with considering not only the cardiological aspects but also the preconditions for primary care and the patients’ point of view. The following experts were recruited by the leaders of the study team and met for several hours to discuss the project: a cardiologist working out of his own office, the chief physician of the internal medicine department of a first-level hospital, a senior cardiologist from a university hospital, two family doctors, a patient representative with experience in guideline development, and a methodologist. The group performed the following tasks:

Provision of advice on development of the questionnaire used to determine primary care physicians’ knowledge of guidelines

Final approval of the questionnaire

Development of a scoring system for evaluation of the completed questionnaire

Provision of advice on development of the indicators used to determine physicians’ compliance with guidelines

Final approval of the indicators

A focus group discussion was held with the experts to inform them about the research goals and to acquire material for development of the questionnaire (1, 2). Discussion and approval of the instruments was accomplished by means of repeated written statements according to the Delphi method (3, 4). Each of the experts received 750 euros towards expenses.

Survey of physicians’ knowledge of guidelines

Development of questionnaire

The questionnaire on treatment of cardiovascular diseases was developed together with the experts in several phases (focus group discussion, Delphi procedure). After input from the focus group the research team put together a catalog of 24 questions. The experts assessed this catalog anonymously in writing in two phases. Every question and the answer categories were considered on the criteria of relevance, comprehensibility, clarity, pertinence, fit, exactness, and exclusivity. The questions and answer categories were evaluated by means of a four-step Likert scale (5) and a written statement.

All of the items eventually included in the questionnaire had been reviewed twice by the experts and achieved at least 85% approval; items that did not meet this criterion were excluded.

Finally the questionnaire was checked for agreement with the recommendations of Guideline No. 9 on heart failure by the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM) (2006) and Version 1.5 of the German National Disease Management Guidelines on CHD (2007). These recommendations had not been published at the time the research proposal was submitted. No modification of the questionnaire content was necessary.

A preliminary investigation of the postal survey was carried out in the development phase for purposes of quality assurance. The instrument was tested with regard to comprehensibility, clarity, order of questions, time taken for completion, and context effects (6); furthermore, the validity of its content was estimated (5). This pre-test was carried out using the concurrent think aloud method by one of the authors (UK) together with five physicians (two family doctors, two internal medicine residents, and one physician in the field of health services research) and one non-physician (a medical sociologist) (7, 8).

Development of the scoring system

After finalization of the questionnaire, an evaluation strategy was agreed with the expert advisory group. It was decided to evaluate physicians’ knowledge of current guidelines on the basis of their answers and to distinguish between “adequate” and “inadequate” knowledge.

The experts were given two principles of evaluation and asked for a written statement:

Principle A—A physician responding to the questionnaire on treatment of cardiovascular diseases possesses adequate knowledge of the guidelines if he/she correctly answers the following three cardinal questions:

Definition of hypertension (question 1 in the instrument)

Procedure for diagnosis of heart failure (question 6)

Drug treatment for CHD (question 11)

These three questions had already been identified as particularly important during development of the questionnaire.

Principle B—A physician responding to the questionnaire on treatment of cardiovascular diseases possesses adequate knowledge of the guidelines if he/she correctly answers 10 of the 15 questions.

The experts initially showed a wide spectrum of opinions with varying preferences. At the suggestion of three experts, the two principles of evaluation were combined, as described in the following.

Scoring system—Adequate knowledge of the guidelines is possessed by physicians who answer 10 or more questions in accordance with the relevant guidelines, including the three cardinal questions (definition of hypertension, diagnosis of heart failure, treatment of chronic CHD).

On one hand, this evaluation strategy takes account of the quantitative dimension of adequate specialist knowledge, because two-thirds of the questions have to be answered correctly. On the other, the strategy does justice to the qualitative dimension: certain items of knowledge are regarded as basic and essential; from an expert’s point of view they are also a sign of adequate specialist knowledge. The expert advisory group as a whole accepted these arguments and unanimously approved the scoring system.

Survey of physicians’ compliance with guidelines

Recruitment of the participating physicians

Of the 33 physicians from the ASHIP Saxony and 43 physicians from the ASHIP North Rhine who volunteered to participate in this part of the study, 15 from each region were selected. On grounds of practicability we chose eight physicians’ offices in Cologne (North Rhine) or within 30 km of Cologne, seven offices in the rural area around Cologne (at least 50 km from Cologne, population below 100 000), eight physicians’ offices in Dresden or Leipzig (Saxony) or within 30 km of the respective city, and seven offices in the rural area around Dresden (at least 50 km from Dresden, population below 100 000); these offices were visited. No other characteristics were considered in choosing the participants.

Acquisition of patient data

It was originally planned to conduct 30 office audits (data collection by a physician from the research team in each office followed by face-to-face discussions with the participating physicians in the case of treatments deviating from the guideline recommendations). Owing to a shortage of resources, however, and also on data protection grounds, this plan had to be abandoned. The data had to be collected by a member of staff in each participating physician’s office. A documentation form was prepared for this purpose. The practicability of this modified procedure was tested in three physicians’ offices in September 2007. In these cases a physician from the research team worked together with a member of staff from the office to collect the data. These data were excluded from analysis, because no member of the research team was involved in acquisition of the data from the remaining offices.

The other 27 physicians’ offices were all visited by the physician from the research team in November or December 2007 to train the respective member of staff in structured data collection. Each office had 3 months to collect the data; two were granted an extension. Spot sampling of the data for control purposes was also not possible on grounds of data protection.

Indicator analysis of patient data in comparison of extreme groups

Exploratory analysis of the patient data with regard to the indicators showed no essential differences in treatment practices between physicians defined as having adequate knowledge of guidelines and those less familiar with current guideline recommendations. This was confirmed by descriptive comparisons between extreme groups.

To this end the patient data of the three “best” and the three “worst” physicians were compared. The three “best” physicians had answered at least 13 questions, including the three cardinal questions, in accordance with the guidelines, while the three “worst” physicians had answered at most nine questions in accordance with the guidelines. There were 133 sets of patient data from the “better” physicians and 135 sets from the “worse” physicians (Table 1).

Furthermore, the patient data (n = 751) from the 18 physicians who answered the question regarding the definition of hypertension in accordance with the guidelines were compared with the patient data from the nine physicians who answered the question inadequately (Table 2).

Because of the sometimes very low numbers of cases, the extreme group comparisons are based on absolute frequency distributions; the relative probabilities are included whenever case numbers suffice.

Assessment of physicians’ compliance with guidelines

The fundamental requirements for determining how closely physicians were adhering to guidelines included the physicians’ willingness to participate, a sufficient number of patient data sets, and identification of suitable indicators.

Recruitment of participating physicians—All physicians who responded to the postal survey on treatment of cardiovascular diseases (n = 1152) were asked in writing whether they would be prepared to take part in a further survey to be carried out at their offices. The aim was to recruit a total of 30 physicians’ offices (ASHIP North Rhine: 15 offices—50% urban, 50% rural; ASHIP Saxony: 15 offices—50% urban, 50% rural). The office survey comprised an office visit by a physician from the research team and, on data protection grounds, structured collection of patient data by specially schooled members of the office staff. The participating primary care physicians received 15 euros per patient included in the survey. A maximum of 50 patients per physician could be documented. The office survey began in November 2007.

Acquisition of patient data—In each primary care physician’s office, the patient data were collected by a member of staff who had been instructed by a physician from the research team. Altogether, data on 1500 patients were expected. The patients eligible for the survey were those aged 40 years or over who attended the physician’s office for any reason on one of three predefined days. The pseudonymized questionnaire on knowledge of guidelines enabled each patient to be classified according to the treating physician’s familiarity with guidelines. The data were evaluated with the aid of the statistical software SPSS 18.0; analysis included calculation of relative and absolute frequencies (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of patient data collected.

| Patient data | Variable |

| General information | Sex |

| Year of birth | |

| Height | |

| Last measured weight | |

| First visit to physician’s office? | |

| Diagnoses | |

| Risk factors | Smoking status |

| Overweight | |

| Data on blood pressure | Last measured blood pressure |

| Number of blood pressure measurements in previous 12 months | |

| Laboratory parameters | Last measured creatinine clearance |

| Last measured creatinine concentration in serum | |

| Last measured total cholesterol concentration | |

| Last measured LDL cholesterol concentration | |

| Number of laboratory controls in previous 12months | |

| Medications | Name of drug |

| Daily dosage | |

| Number of prescribed daily dosages in previous 12months | |

| General measures | Training in self-measurement of blood pressure |

| Training in weight control | |

| Nutritional advice | |

| Support in giving up smoking | |

| Verbal information | |

| Other measures | |

| Cardiological investigations | Number of referrals to a cardiologist in previous 12months |

| Number of echocardiographies (evaluations of pump function) in previous 12 months | |

| Reason for most recent referral to a cardiologist |

Development of an indicator set—The technique used to develop a catalog of indicators for evaluation of physicians’ adherence to guidelines on the basis of the sampled patient data was oriented on the RAND method (19). The factors taken into consideration were the treatment principles deemed relevant by the expert advisory group together with central guideline recommendations and the evidence on which these were founded. The indicators that were considered related to the medications prescribed, diagnostic procedures, and clinical parameters of treatment success. Final selection of indicators for the catalog was based on repeated anonymous written opinions from the experts on the basis of relevant criteria (20– 22). Evaluation of the indicators according to the quality criteria of the QUALIFY instrument (23) was not yet possible at the time our study was carried out. However, the methods overlap. A total of 16 agreed indicators were employed.

Indicator-guided analysis of patient data— Indicator-related evaluation of the patient data to determine physicians’ adherence to guidelines was performed with the aid of the statistical program SPSS 18.0. Absolute and relative frequencies were calculated to reveal, for each indicator, what proportion of the patients had been treated according to guideline recommendations. We then carried out chi-square-based linkage analysis to identify any significant differences in distribution (Did the patient data fulfill the requirements of the given indicator more frequently when they came from the office of a physician with adequate knowledge of guidelines as defined by the operational criteria?). Furthermore, the data were considered descriptively with regard to individual risk constellations and their consequences for treatment (for example: Was medication prescribed for patients with documented hypertension?).

Data from patients aged 80 years or over were excluded from indicator-guided analysis. On the one hand the evidence for guideline recommendations regarding this age group is not always adequate, and on the other hand their doctors may deviate from standard recommendations because of multimorbidity in elderly patients.

Results

Representative survey of physicians’ knowledge of guidelines

The survey was sent to 2500 primary care physicians, 1152 of whom returned questionnaires suitable for analysis. Excluding 31 surveys sent to incorrect addresses, the effective response rate was therefore 47%. The responders were analyzed by ASHIP membership, sex, specialization, and experience (Table 2). With regard to sex distribution and specialization, our sample of physicians did not differ essentially from the overall ASHIP membership in North Rhine and Saxony.

Table 2. Postal survey of physicians: sociodemographic variables and knowledge of guidelines.

| Variable | Coding | n | %*1 |

| ASHIP membership | Saxony | 547 | 48 |

| North Rhine | 605 | 52 | |

| Sex | Female | 495 | 43 |

| Male | 647 | 56 | |

| Specialization | General medicine | 669 | 60 |

| Internal medicine | 332 | 29 | |

| Family doctor | 116 | 10 | |

| Other | 12 | 1 | |

| Experience (years with own office) | Less than 2 years | 81 | 7 |

| 2 to <5 years | 120 | 10 | |

| 5 to <10 years | 157 | 14 | |

| 10 to <15 years | 189 | 17 | |

| 15 to <20 years | 294 | 26 | |

| 20 years or more | 297 | 26 | |

| Knowledge of guidelines | |||

| Proportion of physicians who answered. questions in accordance with guidelines | 5 questions | 3 | |

| 6 questions | 9 | ||

| 7 questions | 21 | 2 | |

| 8 questions | 48 | 5 | |

| 9 questions | 102 | 10 | |

| 10 questions | 111 | 11 | |

| 11 questions | 207 | 20 | |

| 12 questions | 235 | 22 | |

| 13 questions | 175 | 17 | |

| 14 questions | 100 | 10 | |

| 15 questions | 28 | 3 | |

| Hypertension | Number of responders who answered all hypertension questions in accordance with guidelines | 126 | 11 |

| Heart failure | Number of responders who answered all heart failure questions in accordance with guidelines | 264 | 24 |

| Chronic CHD | Number of responders who answered all chronic CHD questions in accordance with guidelines | 811 | 74 |

| Definition of hypertension | Number of responders who answered question regarding definition of hypertension in accordance with guidelines | 663 | 58 |

| Diagnosis of heart failure | Number of responders who answered question regarding diagnostic confirmation of heart failure in accordance with guidelines | 859 | 75 |

| Treatment of chronic CHD | Number of responders who answered question regarding statin treatment in accordance with guidelines | 1?078 | 94 |

| Adequate knowledge of guidelines | Number of responders who answered at least 10 questions in accordance with guidelines, including the three cardinal questions | 437 | 40 |

| Inadequate knowledge of guidelines | Number of responders who failed to meet one of the two criteria (number of questions, cardinal questions) | 665 | 60 |

| N | 1152 |

*1Percentages calculated after exclusion of missing and invalid responses

On average, 11 of the 15 questions on treatment of cardiovascular diseases were answered in accordance with guidelines. Three physicians answered only five questions in accordance with guidelines; 28 (3%) answered all 15 questions in agreement with guideline recommendations. The questions on hypertension were answered in accordance with guidelines by 11% of the responders. A far higher proportion (74%) gave answers to the questions on chronic CHD that conformed adequately to guideline recommendations. According to the operational criteria for this study, 437 (40%) of responding physicians demonstrated adequate knowledge of the guidelines, while 695 did not (Table 2). Logistic regression analysis revealed an insignificant impact of sociodemographic characteristics on physicians’ knowledge of guidelines (McFadden’s pseudo-R2: 0.027).

Exploratory survey of physicians’ compliance with guidelines

A total of 76 physicians’ offices (7%) offered to participate in the office survey. On grounds of resource availability and practicability, 15 offices in and around Cologne and Bonn (North Rhine) and 15 offices in and around either Dresden or Leipzig (Saxony) were selected. After exclusion of the three pre-test offices, data from 27 offices were acquired for analysis.

Comparison of the physicians recruited for the office survey with those who completed the postal questionnaire showed higher proportions of women (52% vs 43%), physicians with their own office for less than 2 years (15% vs 7%), and physicians with their own office for 10 to 14 years (30% vs 17%). The physicians who took part in the office survey answered an average 11 out of the 15 questions in the postal survey in accordance with the guidelines and thus did not differ from the total sample. One participant in the office survey answered seven questions (minimum) and one answered 14 questions (maximum) in accordance with guideline recommendations. Adequate knowledge of the guidelines according to the operational criteria was displayed by 48% (n = 13) of those who took part in the office survey, a slightly higher proportion than in the total sample (Table 3).

Table 3. Physicians who took part in the office survey: sociodemographic characteristics and knowledge of guidelines.

| Variable | Coding | n | % |

| ASHIP membership | Saxony | 15 | 56 |

| North Rhine | 12 | 44 | |

| Sex | Female | 13 | 52 |

| Male | 14 | 48 | |

| Specialization | General medicine | 18 | 67 |

| Internal medicine | 8 | 29 | |

| Family doctor | 1 | 4 | |

| Experience (years with own office) | Less than 2 years | 4 | 15 |

| 2 to <5 years | 2 | 7 | |

| 5 to <10 years | 2 | 7 | |

| 10 to <15 years | 8 | 30 | |

| 15 to <20 years | 5 | 18 | |

| 20 years or more | 5 | 18 | |

| Not stated | 1 | 4 | |

| Knowledge of guidelines | |||

| Proportion of physicians who answered .questions in accordance with guidelines | 7 questions | 1 | 4 |

| 9 questions | 2 | 7 | |

| 10 questions | 4 | 15 | |

| 11 questions | 9 | 33 | |

| 12 questions | 6 | 22 | |

| 13 questions | 4 | 15 | |

| 14 questions | 1 | 4 | |

| Definition of hypertension | Number of responders who answered question regarding definition of hypertension in accordance with guidelines | 18 | 67 |

| Diagnosis of heart failure | Number of responders who answered question regarding diagnostic confirmation of heart failure in accordance with guidelines | 21 | 78 |

| Treatment of chronic CHD | Number of responders who answered question regarding statin treatment in accordance with guidelines | 25 | 93 |

| Adequate knowledge of guidelines | Number of responders who answered at least 10 questions in accordance with guidelines, including the three cardinal questions | 13 | 48 |

| Inadequate knowledge of guidelines | Number of responders who failed to meet one of the two criteria (number of questions, cardinal questions) | 14 | 52 |

| N | 27 |

The 27 physicians’ offices collected data on the treatment of 1318 patients. Data on 21 patients were excluded because their age was below 40 years or not stated. The effective response rate was therefore 96% (n = 1297). After exclusion of those over 79 years of age, treatment data for 1107 patients were eligible for analysis.

More than half of the patients were women (n = 592), and 64% (n = 706) of them were aged 60 years or over. The prevalence of the three target diseases varied considerably among the offices surveyed. Overall, 68% of the patients (n = 749) had arterial hypertension, 24% (n = 269) had CHD, and 7% (n = 79) had heart failure. Forty-two percent of the patients (n = 464) had two or more of the following diagnoses: hypertension, CHD, heart failure, kidney failure, diabetes mellitus. Forty-eight percent of the patients (n = 536) were treated by a physician with adequate knowledge of the guidelines as defined here. The physicians whose knowledge of the guidelines was inadequate according to the operational criteria tended to have documented more patients aged 50 to 59 years (145 vs 93 patients) and fewer patients in the 70 to 79 years age group (148 vs 204 patients). The prevalence of the three target diseases showed no essential differences between physicians with and those without adequate knowledge of guidelines. The number of patients with at least two of the five diseases mentioned above was higher, though not significantly so, for the physicians who had adequate knowledge of the guidelines (243 vs 221 patients) (Table 4).

Table 4. Patient data: demographic characteristics, diseases/physicians’ knowledge of guidelines.

| Physician’s knowledge of guidelines | |||||

| Patient data | Adequate | Inadequate | |||

| Variable | Coding | n | % | n | % |

| Sex | Female | 281 | 52 | 311 | 55 |

| Male | 255 | 48 | 260 | 45 | |

| Age | 40–49 years | 70 | 13 | 93 | 16 |

| 50–59 years | 93 | 17 | 145 | 25 | |

| 60–69 years | 169 | 31 | 185 | 32 | |

| 70–79 years | 204 | 38 | 148 | 26 | |

| Hypertension? | Documented | 373 | 70 | 376 | 66 |

| CHD? | Documented | 140 | 26 | 129 | 23 |

| Heart failure? | Documented | 39 | 7 | 40 | 7 |

| Co-/multimorbidity? | Present | 243 | 45 | 221 | 39 |

| n = 536 (48%) | n = 571 (52%) | ||||

Indicator-guided analysis shows the proportion of patients whose data reveal that they were treated in adherence to the guidelines. This proportion varied from 46% to 94% for the five hypertension-related indicators, from 30% to 87% for the seven heart failure-related indicators, and from 64% to 100% for the four CHD-related indicators. Chi-square-based linkage analysis showed no significant differences in distribution (p ≤ 0.05) for 12 of 16 indicators. In these cases the distribution of the individual indicators (patient data show treatment adhering to guidelines: yes/no) did not differ between the physicians with and those without adequate knowledge of guidelines. For the remaining four indicators (nos. 4, 5, 7, and 11) the patient data showed significant differences between the two groups of physicians: the proportion of patient data from which treatment complying with guidelines could be concluded was higher among physicians who did not know the guidelines adequately (Table 5).

Table 5. Analysis of indicators in the patient data.

| Indicator | All patients | Patients treated by physicians with adequate knowledge of guidelines | Patients treated by physicians with inadequate knowledge of guidelines | Significance (chi-square test) | |||

| Indicator 1 | Proportion of hypertension patients with at least one prescription for an ACE inhibitor/AT1 antagonist, beta-blocker, calcium antagonist, and/or diuretic | ||||||

| 1n = 703 | 94% | n = 345 | 92% | n = 358 | 95% | *3p = 0.130 | |

| 2N = 749 | N = 373 | N = 376 | |||||

| Indicator 2 | Proportion of diabetic hypertension patients on long-term treatment with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans) | ||||||

| n = 234 | 81% | n = 132 | 82% | n = 102 | 79% | p = 0.547 | |

| N = 289 | N = 160 | N = 129 | |||||

| Indicator 3 | Proportion of hypertension patients on beta-blocker treatment with documented CHD | ||||||

| n = 158 | 74% | n = 84 | 74% | n = 74 | 73% | p = 0.877 | |

| N = 214 | N = 113 | N = 101 | |||||

| Indicator 4 | Proportion of hypertension patients with normalized blood pressure of all patients with documented hypertension | ||||||

| n = 335 | 46% | n = 148 | 41% | n = 187 | 50% | p = 0.018 | |

| N = 731 | N = 358 | N = 373 | |||||

| Indicator 5 | Proportion of hypertension patients with at least four documented blood pressure measurements in the previous 12 months of all hypertensive patients | ||||||

| n = 551 | 76% | n = 257 | 71% | n = 294 | 80% | p = 0.009 | |

| N = 728 | N = 360 | N = 368 | |||||

| Indicator 6 | Proportion of heart failure patients with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans) | ||||||

| n = 54 | 68% | n = 26 | 67% | n = 28 | 70% | p = 0.812 | |

| N = 79 | N = 39 | N = 40 | |||||

| Indicator 7 | Proportion of heart failure patients receiving carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, bisoprolol or nebivolol | ||||||

| n = 50 | 63% | n = 19 | 49% | n = 31 | 77% | p = 0.010 | |

| N = 79 | N = 39 | N = 40 | |||||

| Indicator 8* | Proportion of digitalized heart failure patients without simultaneous ACE inhibitor/AT1-receptor antagonist and/or beta-blocker treatment | ||||||

| n = 5 | 21% | n = 1 | 10% | n = 4 | 29% | p = 0.358 | |

| N = 24 | N = 10 | N = 14 | |||||

| Indicator 9 | Proportion of heart failure patients treated with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans), receiving the target dose as daily dose | ||||||

| n = 16 | 30% | n = 7 | 27% | n = 9 | 32% | p = 0.770 | |

| N = 54 | N = 26 | N = 28 | |||||

| Indicator 10* | Proportion of heart failure patients prescribed calcium antagonists (except amlodipine) | ||||||

| n = 10 | 13% | n = 5 | 13% | n = 5 | 12% | p = 1.000 | |

| N = 79 | N = 39 | N = 40 | |||||

| Indicator 11 | Proportion of heart failure patients with documentation of echocardiography or determination of pump function in the previous 12 months | ||||||

| n = 39 | 55% | n = 13 | 38% | n = 26 | 70% | p = 0.009 | |

| N = 71 | N = 34 | N = 37 | |||||

| Indicator 12 | Proportion of heart failure patients with documented weight | ||||||

| n = 66 | 84% | n = 35 | 90% | n = 31 | 78% | p = 0.225 | |

| N = 79 | N = 39 | N = 40 | |||||

| Indicator 13 | Proportion of CHD patients prescribed a thrombocyte aggregation inhibitor | ||||||

| n = 173 | 64% | n = 89 | 64% | n = 84 | 65% | p = 0.800 | |

| N = 269 | N = 140 | N = 129 | |||||

| Indicator 14* | Proportion of CHD patients on nitrates without simultaneous thrombocyte aggregation inhibitor, ACE inhibitor/AT1-receptor antagonist, or beta-blocker treatment | ||||||

| n = 5 | 7% | n = 1 | 4% | n = 4 | 11% | p = 0.200 | |

| N = 77 | N = 39 | N = 38 | |||||

| Indicator 15 | Proportion of post-infarction patients prescribed statins/fibrate | ||||||

| n = 51 | 65% | n = 21 | 75% | n = 30 | 59% | p = 0.219 | |

| N = 79 | N = 28 | N = 51 | |||||

| Indicator 16 | Proportion of CHD patients with documented measurement of blood pressure at least once each year | ||||||

| n = 263 | 100% | n = 137 | 99% | n = 126 | 100% | p = 1.000 | |

| N = 264 | N = 138 | N = 126 | |||||

1n, Number of patients who meet the indicator criterion;

2N, patients with target disease excluding those with no data regarding indicator (= 100%);

3p, chi-square test, exact significance (two-sided).

*Indicator criterion contrary to guideline recommendation. Proportion of patients meeting criterion should be very low or zero

Exploratory analysis of the treatment data with regard to individual risk constellations and their consequences for treatment was severely limited by the low number of patients, but it does point to insufficient treatment intensity. In 52% (n = 367) of hypertension patients receiving drug treatment, for instance, blood pressure had not been restored to normal. Of these 367 patients, 23% (n = 84) were receiving monotherapy and 33% (n = 120) were being treated with two drugs in combination. Patients with diabetes and hypertension benefit from treatment with ACE inhibitors, but 55 (19%) of the 289 diabetics with high blood pressure in this study were not being prescribed ACE inhibitors. Fourteen patients also had documented CHD; six of these were receiving neither ACE inhibitors nor a beta-blocker.

Discussion

Compared with other surveys of primary care physicians, the response rate to our questionnaire was high at 47% (24, 25, e7, e8). With regard to previous similar studies (12), our representative findings indicate increasing awareness of the content of guideline recommendations for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Nevertheless, there is considerable potential for improvement in 60% of doctors providing primary care.

Contrary to what is generally assumed, exploratory analysis of the selected indicators showed no essential differences in treatment between physicians with adequate knowledge of the guidelines and those who were less familiar with current guideline recommendations. This was confirmed in descriptive comparisons of the treatment data in extreme groups (comparison of the three “best” and the three “worst” physicians; comparison of patient data from physicians who answered the question regarding the definition of hypertension in accordance with the guidelines and those who did not). It therefore seems that physicians’ familiarity with guidelines does not, as previously thought, translate into better implementation of the guidelines in daily practice. In this light, purely cognitive strategies to improve the quality of health care need to be reconsidered.

The treatment of patients with particular risk constellations was not a primary consideration of this study. For this reason the case numbers were low and do not permit the conclusion of generalized failure to make proper allowance for risks in patient treatment. Taken together with the results of other investigations (e9– e11), however, the signals generated here can be interpreted as showing that treatment decisions are based less on medical data than on other practice-relevant factors. These factors may include the internal organizational routines of the physician’s office, financial parameters, or patient-related aspects. Differentiation of these facultative relationships was not a goal of this project, neither is it feasible.

The interpretation of the findings is limited by the following factors:

The results are based on a representative survey of physicians’ knowledge of guidelines and on an exploratory investigation of physicians’ adherence to guidelines. Their validity is limited by the cross-sectional design and by the sometimes low numbers of cases in the exploratory part of the study. Longitudinal studies are therefore essential.

Knowledge of the guidelines was not tested directly; rather, theoretical treatment strategies were selected with the aid of case-oriented questions. An agreed scoring system was then used to divide the physicians into two groups—“adequate” and “inadequate” knowledge of guidelines—on the basis of their responses.

The physicians’ adherence to the guidelines was ascertained by means of indicator-guided analysis of patient data. On data protection grounds, these data were collected by a specially schooled member of staff in each doctor’s office. Errors in data acquisition cannot be completely ruled out.

The results of indicator evaluation and the findings on adaptation of treatment to allow for individual risk constellations are based on an exploratory investigation with sometimes very low numbers of cases.

Financial restrictions did not permit discussions with the physicians to find out why they deviated from the guidelines in concrete individual cases (patient’s preferences, quality of life, prioritization in the case of multimorbidity).

Although the above-mentioned practical constraints do not permit any conclusions regarding the causal link between physicians’ knowledge of and compliance with guidelines, our results point the way for future research. Increased efforts should be made—as has already happened in some integrated care projects—to implement guideline recommendations as in-process control variables in standardized software. This is particularly important because it cannot be excluded that feedback from targeted, controlled action leads to a secondary gain in knowledge. This could be the reason why the responses to the questions on CHD, for which there is a Disease Management Program in Germany, were in accordance with the guidelines much more frequently than was the case for arterial hypertension. These incompletely resolved questions should form the stepping-off point for future investigations.

Key Messages.

The majority of the primary care physicians surveyed (74%) answered the questions on chronic CHD in accordance with guideline recommendations. In contrast, only 11% and 24% respectively gave answers to the questions on arterial hypertension and heart failure that conformed to the guidelines.

Only 40% of the physicians possessed adequate knowledge of cardiovascular treatment guidelines as defined by the operational criteria.

Sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, experience, specialization, location) had little impact on physicians’ knowledge of guidelines.

The exploratory analysis of indicators showed no essential differences in the treatment given between physicians who knew the guidelines adequately and those who were less familiar with the guidelines.

Therefore, knowledge of treatment guidelines seems not to constitute a good indicator of implementation of guidelines into routine practice.

eTable 1. Comparison of extreme groups: 133 patients treated by three physicians who answered at least 13 questions, including the three cardinal questions, in accordance with the guidelines ("high" knowledge of guidelines) versus 135 patients treated by three physicians who answered at most nine questions in accordance with the guidelines ("low" knowledge of guidelines).

| Indicator | All patients | Patients of three physicians with "high" knowledge of guidelines | Patients of three physicians with "low" knowledge of guidelines | |||

| Indicator 1 | Proportion of hypertension patients with at least one prescription for an ACE inhibitor/AT1 antagonist, beta-blocker, calcium antagonist, and/or diuretic | |||||

| n1 = 171 | 98% | n = 96 | 98% | n = 75 | 97% | |

| N 2 = 175 | N = 98 | N = 77 | ||||

| Indicator 2 | Proportion of diabetic hypertension patients on long-term treatment with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans) | |||||

| n = 69 | 84% | n = 47 | 82% | n = 22 | 88% | |

| N = 82 | N = 57 | N = 25 | ||||

| Indicator 3 | Proportion of hypertension patients on beta-blocker treatment with documented CHD | |||||

| n = 35 | 79% | n = 26 | 81% | n = 9 | 75% | |

| N = 44 | N = 32 | N = 12 | ||||

| Indicator 4 | Proportion of hypertension patients with normalized blood pressure of all patients with documented hypertension | |||||

| n = 85 | 49% | n = 50 | 51% | n = 35 | 47% | |

| N = 172 | N = 97 | N = 75 | ||||

| Indicator 5 | Proportion of hypertension patients with at least four documented blood pressure measurements in the previous 12 months of all hypertensive patients | |||||

| n = 125 | 73% | n = 62 | 64% | n = 63 | 84% | |

| N = 172 | N = 97 | N = 75 | ||||

| Indicator 6 | Proportion of heart failure patients with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans) | |||||

| n = 8 | n = 4 | n = 4 | ||||

| N = 10 | N = 5 | N = 5 | ||||

| Indicator 7 | Proportion of heart failure patients receiving carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, bisoprolol or nebivolol | |||||

| n = 7 | n = 3 | n = 4 | ||||

| N = 10 | N = 5 | N = 5 | ||||

| Indicator 8* | Proportion of digitalized heart failure patients without simultaneous ACE inhibitor/AT1-receptor antagonist and/or beta-blocker treatment | |||||

| n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 0 | ||||

| N = 4 | N = 2 | N = 2 | ||||

| Indicator 9 | Proportion of heart failure patients treated with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans), receiving the target dose as daily dose | |||||

| n = 3 | n = 1 | n = 2 | ||||

| N = 8 | N = 4 | N = 4 | ||||

| Indicator 10* | Proportion of heart failure patients prescribed calcium antagonists (except amlodipine) | |||||

| n = 10 | n = 5 | n = 5 | ||||

| N = 10 | N = 5 | N = 5 | ||||

| Indicator 11 | Proportion of heart failure patients with documentation of echocardiography or determination of pump function in the previous 12 months | |||||

| n = 6 | n = 2 | n = 4 | ||||

| N = 9 | N = 5 | N = 4 | ||||

| Indicator 12 | Proportion of heart failure patients with documented weight | |||||

| n = 7 | n = 5 | n = 2 | ||||

| N = 10 | N = 5 | N = 5 | ||||

| Indicator 13 | Proportion of CHD patients prescribed a thrombocyte aggregation inhibitor | |||||

| n = 35 | 67% | n = 27 | 71% | n = 8 | 61% | |

| N = 51 | N = 38 | N = 13 | ||||

| Indicator 14* | Proportion of CHD patients on nitrates without simultaneous thrombocyte aggregation inhibitor, ACE inhibitor/AT1-receptor antagonist, or beta-blocker treatment | |||||

| n = 0 | n = 0 | n = 0 | ||||

| N = 8 | N = 4 | N = 4 | ||||

| Indicator 15 | Proportion of post-infarct patients prescribed statins/fibrate | |||||

| n = 10 | n = 7 | n = 3 | ||||

| N = 14 | N = 10 | N = 4 | ||||

| Indicator 16 | Proportion of CHD patients with documented measurement of blood pressure at least once each year | |||||

| n = 37 | 74% | n = 27 | 71% | n = 10 | 83% | |

| N = 50 | N = 38 | N = 12 | ||||

n1Number of patients who meet the indicator criterion; N2, patients with target disease excluding those with no data regarding indicator (= 100%)

*Indicator criterion contrary to guideline recommendation. Proportion of patients meeting criterion should be very low or zero.

eTable 2. Comparison of extreme groups: 751 patients treated by 18 physicians who answered the question regarding the definition of hypertension in accordance with the guidelines versus 356 patients treated by the nine physicians who did not answer the question adequately.

| Indicator | All patients | Patients of physicians with adequate hypertension answer | Patients of physicians with inadequate hypertension answer | |||

| Indicator 1 | Proportion of hypertension patients with at least one prescription for an ACE inhibitor/AT1 antagonist, beta-blocker, calcium antagonist, and/or diuretic | |||||

| n1 = 703 | 94% | n = 469 | 93% | n = 234 | 95% | |

| N 2 = 749 | N = 504 | N = 245 | ||||

| Indicator 2 | Proportion of diabetic hypertension patients on long-term treatment with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans) | |||||

| n = 234 | 81% | n = 165 | 81% | n = 69 | 81% | |

| N = 289 | N = 204 | N = 85 | ||||

| Indicator 3 | Proportion of hypertension patients on beta-blocker treatment with documented CHD | |||||

| n = 158 | 46% | n = 228 | 47% | n = 107 | 44% | |

| N = 214 | N = 487 | N = 244 | ||||

| Indicator 4 | Proportion of hypertension patients with normalized blood pressure of all patients with documented hypertension | |||||

| n = 335 | 49% | n = 50 | 51% | n = 35 | 47% | |

| N = 731 | N = 97 | N = 75 | ||||

| Indicator 5 | Proportion of hypertension patients with at least four documented blood pressure measurements in the previous 12 months of all hypertensive patients | |||||

| n = 551 | 76% | n = 369 | 75% | n = 182 | 76% | |

| N = 728 | N = 490 | N = 238 | ||||

| Indicator 6 | Proportion of heart failure patients with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans) | |||||

| n = 54 | 68% | n = 36 | 68% | n = 18 | 69% | |

| N = 79 | N = 53 | N = 26 | ||||

| Indicator 7 | Proportion of heart failure patients receiving carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, bisoprolol or nebivolol | |||||

| n = 50 | 63% | n = 29 | 55% | n = 21 | 81% | |

| N = 79 | N = 53 | N = 26 | ||||

| Indicator 8* | Proportion of digitalized heart failure patients without simultaneous ACE inhibitor/AT1-receptor antagonist and/or beta-blocker treatment | |||||

| n = 5 | 21% | n = 3 | 18% | n = 2 | 28% | |

| N = 24 | N = 17 | N = 7 | ||||

| Indicator 9 | Proportion of heart failure patients treated with ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor antagonists (sartans), receiving the target dose as daily dose | |||||

| n = 16 | 30% | n = 9 | 25% | n = 7 | 39% | |

| N = 54 | N = 36 | N = 18 | ||||

| Indicator 10* | Proportion of heart failure patients prescribed calcium antagonists (except amlodipine) | |||||

| n = 10 | 13% | n = 7 | 13% | n = 3 | 11% | |

| N = 79 | N = 53 | N = 26 | ||||

| Indicator 11 | Proportion of heart failure patients with documentation of echocardiography or determination of pump function in the previous 12 months | |||||

| n = 39 | 55% | n =23 | 49% | n = 16 | 67% | |

| N = 71 | N = 47 | N = 24 | ||||

| Indicator 12 | Proportion of heart failure patients with documented weight | |||||

| n = 66 | 84% | n = 41 | 77% | n = 25 | 96% | |

| N = 79 | N = 53 | N = 26 | ||||

| Indicator 13 | Proportion of CHD patients prescribed a thrombocyte aggregation inhibitor | |||||

| n = 173 | 64% | n = 125 | 64% | n = 48 | 65% | |

| N = 269 | N = 195 | N = 74 | ||||

| Indicator 14* | Proportion of CHD patients on nitrates without simultaneous thrombocyte aggregation inhibitor, ACE inhibitor/AT1-receptor antagonist, or beta-blocker treatment | |||||

| n = 5 7 | 7% | n = 4 | 7% | n = 1 | 5% | |

| N = 7 | N = 58 | N = 19 | ||||

| Indicator 15 | Proportion of post-infarct patients prescribed statins/fibrate | |||||

| n = 51 | 65% | n = 33 | 59% | n = 18 | 78% | |

| N = 79 | N = 56 | N = 23 | ||||

| Indicator 16 | Proportion of CHD patients with documented measurement of blood pressure at least once each year | |||||

| n = 263 | 100% | n = 191 | 99% | n = 72 | 100% | |

| N = 264 | N = 192 | N = 72 | ||||

n1Number of patients who meet the indicator criterion; N2, patients with target disease excluding those with no data regarding indicator (= 100%)

*Indicator criterion contrary to guideline recommendation. Proportion of patients meeting criterion should be very low or zero.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

The authors thank the members of the expert advisory group—Dr. Sigrid Eufinger, Dr. Joachim Feßler, Prof. Markus Flesch, Dr. Ady Osterspey, Prof. Christoph Pohl, Prof. Gernot Waßmer, Dr. Karl-Gustav Werner—for their assistance and are grateful to all those who took part in the survey. Special thanks are due to all participating primary care physicians and their office staff who willingly gave their time; without their commitment this project could not have been completed. The authors are also grateful to the German Medical Association for its support (project no. 06–39) and to their mentor for this project, Prof. H.-K. Selbmann.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The Primary Health Care Research Group (PMV forschungsgruppe) receives project support from statutory health insurers (Federal Association of the AOK, AOK Hesse, AOK Plus, AOK Baden-Württemberg, LKK Baden-Württemberg), ministries (Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Federal Ministry of Health, Hessian Ministry of Social Affairs), foundations (Boll Foundation, Lesmüller Foundation), and pharmaceutical companies (Sanofi-Aventis, Sanofi Pasteur, MSD, Bayer-Schering, Novo Nordisk, Abbott, Janssen-Cilag, Merz). I. Schubert has received no personal honoraria. The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Cleland JG, Cohen-Solal A, Aguilar JC, Dietz R, Eastaugh J, Follath F, et al. Management of heart failure in primary care (the IMPROVEMENT of Heart Failure Programme): an international survey. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1631–1639. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider F, Menke R, Härter M, Salize HJ, Janssen B, Bergmann F, et al. Sind Bonussysteme auf eine leitlinienkonforme haus- und nervenärztliche Depressionsbehandlung übertragbar? Nervenarzt. 2005;76:308–314. doi: 10.1007/s00115-004-1689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steel N, Bachmann M, Maisey S, Shekelle P, Breeze E, Marmot M, et al. Self reported receipt of care consistent with 32 quality indicators: national population survey of adults aged 50 or more in England. Br Med J. 2008;337 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrier BM, Woodward CA, Cohen M, Williams AP. Clinical practice guidelines. New-to-practice family physicians’ attitudes. Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:463–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasenbein U, Schulze A, Busse R, Wallesch CW. Ärztliche Einstellungen gegenüber Leitlinien. Eine empirische Untersuchung in neurologischen Kliniken. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;(05):332–341. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer J, Piterman L. The attitudes of Australian GPs to evidence-based medicine: a focus group study. Family Practice. 1999;16(6):627–632. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.6.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tunis SR, Hayward RS, Wilson MC, Rubin HR, Bass EB, Johnston M, et al. Internists’ Attitudes about Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(11):956–963. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-11-199406010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schubert I, Egen-Lappe V, Heymans L, Ihle P, Feßler J. Gelesen ist noch nicht getan: Hinweise zur Akzeptanz von hausärztlichen Leitlinien. Eine Befragung in Zirkeln der Hausarztzentrierten Versorgung. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen. 2009;103:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagemeister J, Schneider CA, Barabas S, Schadt R, Wassmer G, Mager G, et al. Hypertension guidelines and their limitations - the impact of physicians’ compliance as evaluated by guideline awareness. J Hypertens. 2001;19(11):2079–2086. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200111000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komajda M, Follath F, Swedberg K, Cleland J, Aguilar JC, et al. The study group of diagnosis of the working group on Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. The EuroHeart Failure Survey programme - a survey on the quality of care among patients with heart failure in Europe. Part 2: treatment. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(5):464–474. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00700-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flesch M, Komajda M, Lapuerta P, Hermans N, Pen CL, Gontales-Juanatey J-R, et al. Leitliniengerechte Herzinsuffizienzbehandlung in Deutschland. Dtsch med Wochenschr. 2005;130(39):2191–2197. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagemeister J, Schneider C, Diedrichs H, Mebus D, Pfaff H, Wassmer G, et al. Inefficacy of different strategies to improve guideline awareness - 5-year follow-up of the hypertension evaluation project (HEP) Trials. 2008;9(39):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baberg HT, Yazaar A, Brechmann T, Grewe P, Kugler J, de Zeeuw J. Versorgungsqualität im medikamentösen und präventiven Bereich bei Patienten mit und ohne koronare Herzkrankheit. Med Klin. 2004;99:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00063-004-1004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Löwel B, Engel S, Hörmann A, Bolte HD, Keil U. Akuter Herzinfarkt und plötzlicher Herztod aus epidemiologischer Sicht. Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin. 1999;36:625–661. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prugger C, Heuschmann PU, Keil U. Epidemiologie der Hypertonie in Deutschland und weltweit. Herz. 2006;31(4):287–293. doi: 10.1007/s00059-006-2818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why Don’t Physicians Follow Clinical Practice Guidelines? A Framework for Improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol.Assess. 2004;8 doi: 10.3310/hta8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heneghan C, Perera R, Mant D, Glasziou P. Hypertension guideline recommendations in general practice: awareness, agreement, adoption, and adherence. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(545):948–952. doi: 10.3399/096016407782604965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall M, Roland M, Campbel S, Kirk S, Reeves D. Santa Monica, CA, USA: The Nuffield Trust; RAND; 2003. Measuring general practice. A demonstration project to develop and test a set of primary care clinical quality indicators; pp. 4–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326(7393):816–819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health, British Medical Association. Quality and Outcomes Framework Guidance. www.dh.gob.uk/PolicyandGuidance/OrganisationPolicy/PrimaryCare. 2006. Jan 09,

- 22.Altenhofen L, Brech W, Brenner G, Geraedts M, Gramsch E, Kolkmann F-W, et al. Beurteilung klinischer Messgrößen des Qualitätsmanagements - Qualitätskriterien und -indikatoren in der Gesundheitsversorgung. Konsenspapier der Bundesärztekammer, der Kassenärztlichen Bundesvereinigung und der AWMF. ZaeFQ. 2001;96:2–15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiter A, Fischer B, Kötting J, Geraedts M, Jäckel WH, Döbler K. QUALIFY: Ein Instrument zur Bewertung von Qualitätsindikatoren. ZaeFQ. 2008;101:683–688. doi: 10.1016/j.zgesun.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grava-Gubins I, Scott S. Effects of various methodologic strategies. Survey response rate among Canadian physicians and physicians-in-training. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1424–1430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brinkmann A. Niedergelassene Ärzte als Kunden des Krankenhauses - eine empirische Untersuchung der Determinanten von Einweiserzufriedenheit. Inaugural-Dissertation, Medizinische Fakultät der Universität zu Köln. 2007 Dezember; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenbaum TL. A Practical Guide for Group Facilitation. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2000. Moderating Focus Groups. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krueger R A Analyzing & Reporting Focus Group Results. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aichholzer G. Das ExpertInnen-Delphi: Methodische Grundlagen und Anwendungsfeld Technology Foresight: Das Experteninterview. In: Bogner A, Littig B, Menz W, editors. Theorie, Methode, Anwendung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag; 2005. pp. 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Häder M, Häder S. Neuere Entwicklungen bei der Delphi-Methode. Literaturbericht II. ZUMA-Arbeitsbericht. 1998;05:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bortz J, Döring N. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2005. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler; pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porst R. Im Vorfeld der Befragung: Planung, Fragebogenentwicklung, Pretesting. ZUMA-Arbeitsbericht. 1998;02:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Land A, Pfaff H, Toellner-Bauer U, Scheibler F, Freise DC. Qualitätssicherung des Kölner Patientenfragebogens durch kognitive Pretest-Techniken. Der Kölner Patientenfragebogen (KPF): Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung der Einbindung des Patienten als Kotherapeuten. In: Pfaff H, Freise DC, Mager G, Schrappe M, editors. Sankt Augustin: Asgard-Verlag; 2003. pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prüfer P, Rexroth M. Verfahren zur Evaluation von Survey-Fragen: Ein Überblick. ZUMA-Nachrichten. 1996;39:95–116. [Google Scholar]

- e1.Deutschen Hochdruckliga e.V. Leitlinien zur Diagnostik und Therapie der arterielle Hypertonie. http://www.paritaet.org/RR-Liga/Hypertonie-Leitlinien05.pdf. 2005. (27.12.2010)

- e2.Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kardiologie - Herz- und Kreislaufforschung e.V. Leitlinien zur Therapie der chronischen Herzinsuffizienz. Z Kardio. 2005;94:488–509. doi: 10.1007/s00392-005-0268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Leitliniengruppe Hessen - Hausärztliche Pharmakotherapie. Leitlinie zur Therapie der Herzinsuffizienz. 2006. Version 3.00. [Google Scholar]

- e4.Therapieempfehlung der Arzneimittelkommission der Deutschen Ärzteschaft, inhaltlich abgestimmt mit der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kardiologie. Koronare Herzkrankheit. 2004.

- e5.Dietz R, Rauch B. „Leitlinie zur Diagnose und Behandlung der chronischen koronaren Herzerkrankung“ der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kardiologie - Herz- und Kreislaufforschung eV. 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Leitliniengruppe Hessen - Hausärztliche Pharmakotherapie. 2004. Leitlinie zur Therapie der stabilen Angina pectoris und der asymptomatischen koronaren Herzerkrankung. Version 2.02. [Google Scholar]

- e7.Obermann K, Rauert R, Görlitz A, Müller P. Umfrage: Nur noch zwei Drittel des Praxisumsatzes aus der GKV. www.aerzteblatt.de/aufsaetze/0401. 2010 May 27; [Google Scholar]

- e8.Schneider CA, Hagemeister J, Pfaff H, Mager G, Höpp HWH. Leitlinienadäquate Kenntnisse von Internisten und Allgemeinmedizinern am Beispiel der arteriellen Hypertonie. ZaeFQ. 2001;95:339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Böhler S, Scharnagl H, Freisinger F, et al. Unmet needs in the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia in the primary care setting in Germany. Atherosclerosis. 2007;190(2):397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Lenzen MJ, Boersma E, Reimer WJ, et al. Under-utilization of evidence-based drug treatment in patients with heart failure is only partially explained by dissimilarity to patients enrolled in landmark trials: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Heart Failure. European Heart Journal. 2005;26(24):2706–213. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Geller JC, Cassens S, Brosz M, Keil U, Bernarding J, Kropf S, et al. Achievement of guideline-defined treatment goals in primary care: the German Coronary Risk Management (CoRiMa) study. European Heart Journal. 2007;28(24):3051–3058. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]