Abstract

Young, homeless women often become pregnant, but little is known about how street youth experience their pregnancies. We documented 26 pregnancy outcomes among 13 homeless women (ages 18–26) and eight homeless men through interviews and participant-observation. Eight pregnancies were voluntarily terminated, three were miscarried, and fifteen were carried to term. Regardless of pregnancy outcome, street youths’ narratives focused on ambivalence about parenting, traumatic childhood experiences, and current challenges. Despite significant obstacles, almost all were convinced of their personal capacity to change their lives. While most wanted to be parents, the majority lost custody of their newborns and consequently associated contact with medical and social services with punitive outcomes. Most of the youth who chose to terminate successfully sought safe medical care. We offer recommendations for changing the approach of services to take full advantage of pregnancy as a potential catalyst event for change in this highly vulnerable and underserved population.

Keywords: Homeless youth, pregnancy, decision-making, services

I chose this. It was my responsibility to be out on the street and take care of myself. I’m old enough to where I can support myself, take care of myself if I want to, and I’m choosing not to. So, it’s not my parent’s or anybody else’s fault. It’s mine if I get in trouble or I end up getting hurt somehow.

—Ashley, 18 year-old pregnant homeless woman

Homeless young women are almost five times more likely to become pregnant1 and far more likely to experience multiple pregnancies2 than housed young women. Very little is known, however, about how homeless youth experience their pregnancies or the ways in which they negotiate difficult life circumstances during the process. The little that is known about how homeless youth conceptualize pregnancy comes from Saewyc’s study of the experiences of “out of home” young women (17 to 19 year old) who chose to parent.3 These women all described complicated relationships with their families of origin and with partners, encompassing violence, abandonment, love, and hope for a better future for themselves and their unborn children. Homeless men are conspicuously absent from the literature on pregnancy and parenting (with some exceptions4,5). We describe the results of a qualitative study aimed at understanding the experience of pregnancy decision-making among young homeless men and women in Berkeley, California.

The majority of homeless youth flee to the streets to escape their families of origin.6,7,8,9 They report traumatic childhoods characterized by neglect, physical violence, and emotional and/or sexual abuse by their family or institutional caregivers.10,11,12,13 Saewyc (2003) and others have also documented that becoming pregnant is one of the primary reason girls leave or are kicked out of their homes.14 Many of the same risk factors that place youth at risk for homelessness are strong predictors of early and unplanned pregnancies among young, homeless women. Haley et al. found that homeless women 14 to 25 years of age who became pregnant were more likely to have experienced intra-familial incest, sexual abuse at an early age, and more severe sexual abuse than young, homeless women who do not become pregnant.15 They were also more likely to have left their homes involuntarily, experienced homelessness at a younger age, and initiated drug and alcohol consumption earlier in life. Other factors that contribute to unintentional pregnancy and negative health outcomes among young homeless women include participation in survival sex16 and barriers to regular supplies of contraceptives and condoms.17,18

The gendered patterns of intimate partner violence among homeless couples may contribute to unintentional pregnancy. Saewyc, Magee, and Pettingell describe the structural vulnerability of young, homeless women engaged in sexually exploitative relationships in which they have little power to negotiate either contraception to prevent unintended pregnancy or condom use to reduce the risk of HIV or sexually transmitted infections.19 Bourgois, Price, and Moss document how drug-using women on the street are forced to seek male companions to protect them from sexual predation by other men and to facilitate the acquisition of money, drugs, and other goods. These researchers documented the ways in which violence within homeless couples, including physical and/or mental abuse and aggression, often becomes the way in which love, affection, and caring are expressed. In the case of women who are pressured to share injection paraphernalia by jealous and controlling partners, this gendered dynamic promotes exposure to infectious disease, especially hepatitis C.20 Bourgois and Shonberg documented similar dynamics for risky health practices among male injection partners on the street, most of whom had histories of childhood abuse.6

Methods

Population and setting

Our study focused on the youth who congregated in the Telegraph/Haste area, a place well-known as a center for the Berkeley homeless population on the perimeter of the University of California, Berkeley. Consistent with our fieldwork observations, an unpublished survey conducted by the City of Berkeley Assistant Mayor’s Office in 1996 found that approximately 30–40 youths inhabited the Telegraph/Haste area at any one time.21 Most of these youths were male, White and over eighteen years of age. About half remained in the area for most of the year, while the other half were transient self-identified “travelers” who adhere to a counter-culture youth identity that opposes middle or working class values and 9-to-5 employment. They generate their income primarily by panhandling, street corner drug selling, petty theft, and occasional day labor. They survive nomadically by hitchhiking or riding freight trains illegally around North America. Most of these youths had lived on the streets for one to five years. There were some older White men who had been on the street for 20 years yet who still associate with White, counter-cultural traveling street youth, rather than with the older homeless population, which was primarily African American in Berkeley. The counter-culture of Bay Area homeless youth has been described elsewhere.22,23,24

According to the Alameda County Homeless Continuum of Care 2003 survey, there were 850 homeless people in Berkeley, California, a city with a total population of 100,000.25 Youth were said to constitute only 6% of the homeless population. This is likely an underestimate since homeless youth are known to avoid the adult-based services where the homeless were counted.

Study sample and recruitment

Our study was primarily based at the Suitcase Clinic, a weekly, university-affiliated, student-run drop-in center for homeless youth providing a variety of free services. Despite its name, Suitcase Clinic is not primarily a medical organization. Though located in a church common room, it involves no religious activities. Youth generally spend the entire evening in the locale, receive a meal and are offered medical, legal, social work, chiropractic, and acupuncture services. They are not required to engage with any services and many of the youth in fact spent the majority of their time simply eating and chatting with one another or with staff.

From July through December 2005, approximately 100 women attending the clinic were given an informational sheet about the project at initial sign-in. We recruited women who were 18 to 26 years old and reported being homeless during a current or past pregnancy. All women who disclosed pregnancies during this time agreed to participate in the study. Women were also approached if they appeared pregnant during participant-observation conducted by the first author who visited common “hang out” locations frequented by homeless youth. Male partners who were involved in the pregnancies were also recruited regardless of their age. Male participants were recruited through their female partners, with the exception of one man, who was interviewed independently. Following a protocol approved by the University of California, Berkeley’s Institutional Review Board, written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. We have assigned participants pseudonyms to protect their confidentiality.

Data collection and analysis

The first author, a White female medical student in her late twenties with a graduate degree in anthropology, conducted participant observation and conversational interviews in the street-based locales where street youth congregated as well as at in the Suitcase Clinic. The bulk of the data on the experience of pregnancy came from participant observation notes and 21 semi-structured, transcribed in-depth interviews that followed an interview guide. Eleven of the interviews were with women alone, four with men alone, and five with couples; one interview included two women. These interviews were supplemented by observational notes that were recorded and coded. Each interview addressed core concepts, including path to homelessness, family life, current living situation, previous and/or current pregnancy experience, decision-making rationale regarding these pregnancies, future goals and expectations, and interaction with social and health services and opinion of these services. An informal, non-judgmental, conversational tone was adopted to minimize impressions and socially desirable responses to follow-up questions regarding charged topics such as sex, violence, drugs, childhood domestic trauma, income generation, and risk-taking. Interviews lasted one to three hours and were recorded and transcribed. Following the grounded theory approach routinely employed in participant-observation research, conversational interview methodology allowed for flexibility to explore and iteratively compare new themes that were raised by different participants. When possible, the validity of responses was triangulated with direct observations of the actual behaviors of these same respondents in their everyday environment. These observations were recoded in detailed field notes.

Field notes and interview transcriptions were coded with Nvivo software26 following Strauss and Corbin’s grounded theory approach as interpreted by Creswell.27 We identified themes as being important when they were raised by multiple participants. Simultaneous data analysis of interviews and participant observation allowed for the integration of emerging hypotheses into the semi-structured interview guide for further, more detailed documentation, exploration, and testing through ongoing participant-observation and further conversational interviews in the street youths’ normal environment. Interviews and field notes were re-read iteratively to develop new codes and to refine existing codes. Special attention was given to recognizing patterns in pregnancy narratives that shaped the rationales for personal decision-making. Analysis included summary memos on emerging themes and iteratively revised interview guides and concept maps (which were discussed regularly with the second and third authors who are both experienced in epidemiological and participant observation ethnographic research with street-based populations). 6,28,29 During the final stages of analysis, the first author also discussed and received feedback about the findings from several participants from the study population.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Thirteen women and eight men were interviewed. Eighteen youth identified themselves as White. One woman identified as herself as Irish-African American and two men as African American. The men were older than their partners by an average of five years. The women reported greater levels of personal trauma than the men. Overall, the women left home at younger ages than the men. On average, the women also had less education. They more frequently reported histories of childhood sexual abuse, mental illness (including depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia) and involuntary institutional care (in foster homes and/or psychiatric facilities). All of the youth described troubled relationships with parents, including histories of neglect, physical abuse, parental drug problems, and/or multiple moves during childhood. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Women = 13 | Men = 8 | |

|---|---|---|

| Ages (years) | 18–26 | 22–36 |

| First left home (age) | 11–20 | 17–20 |

| History of sexual abuse | 6 | 1 |

| Institutional care | 5 | 1 |

| Mental illness diagnosis | 10 | 2 |

| Educational status | 3 high school | 3 high school |

| 5 General Education Diploma (GED) | 4 GED | |

| 5 Less than high school | 1 Less than high school |

Pregnancy status

Four of the thirteen women were pregnant at the time of the first interview (between eight and 38 weeks gestation). All four of these women and their four partners were re-interviewed (between one and four times). The remaining participants were interviewed at least once about a previous pregnancy that had occurred between three months and three and a half years prior to participation in the study.

Five of the thirteen women and four of the eight men had experienced multiple pregnancies. Two women reported two pregnancies, one woman reported three pregnancies, and two women reported four pregnancies. All four men reported fathering two pregnancies.

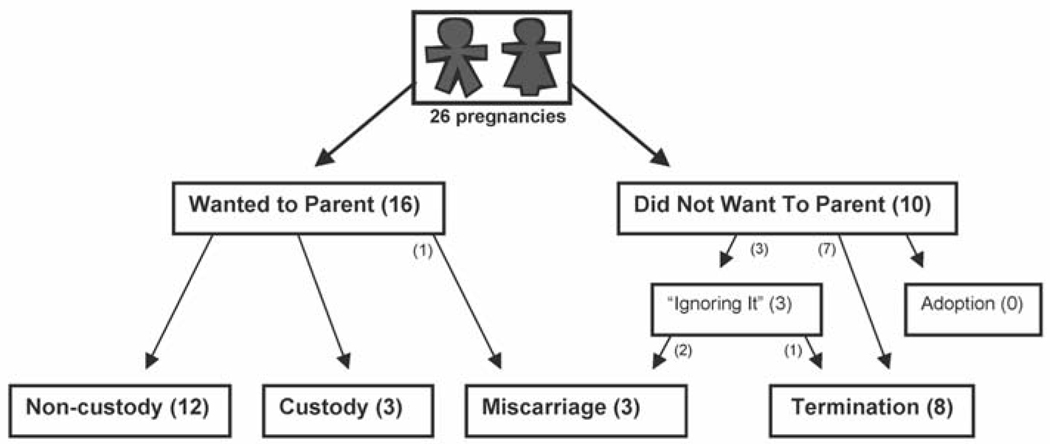

Added together, this sample of 21 men and women had experienced a total of 26 pregnancies. Eight of the pregnancies were voluntarily terminated; three ended in miscarriage; and 15 were carried to term. Of these 15 newborns, only three remained in their parents’ custody. The remaining 12 newborns were removed from their birth mothers by social services and placed with grandparents, a former partner, or in foster care. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Pregnancy outcomes.

Pregnancy narratives—Decision-making

We first describe the experience of pregnancy and decision-making among our participants and the key factors youth describe as influencing that process.

Couple as locus of decision-making

Despite espousing anti-authoritarian and anti-institutional values consistent with their counter-cultural identities, over half of the youth (14 of 20) were in long-term relationships and considered themselves to be “street married,” referring to their partners as “my husband” or “my wife.” They portrayed their pregnancy decision-making as a collaborative effort within the couple. All reported confronting profound relationship difficulties however, triggered by the pregnancy decision-making process. They often attributed these tensions to legacies of domestic conflict from their family-of-origin and/or from previous conflict-ridden sexual partnerships.

Gena is a woman who was sexually abused by her stepfather. Her partner of two years, Frank, was brutally abused and neglected by both his birth and foster families. Gena explained:

Kids! The kind of childhood we had, that was the last thing that we ever thought about having . . . We have no role models for parenting . . . . My background and his background are not stable. So it’s obvious that we’re not going to be the perfectly compatible couple. [When we were making the decision about whether to become parents] that was the only time in our relationship that violence between us was involved.

Arguments, sometimes leading to physical violence, occurred most frequently between partners who disagreed about whether or not to terminate the pregnancy. This was particularly true for those couples who separated before or during the pregnancy decision-making process. Nevertheless, despite the dissolution of several of the relationships, all of the participants who were initially partnered continued to discuss the outcome of the pregnancy with their partners.

[The pregnancy] kind of drew us together . . . let’s just get this done with and deal with us after this. (Adam, 29 year-old man)

Although couples negotiated and/or argued over the outcome of the pregnancy, all participants agreed that the woman ultimately had the right to make the final decision about the pregnancy.

Participants expressed determination not to replicate the troubled childhoods they and their peers had survived. They also acknowledged the precariousnous of their situations and listed money, unstable housing, unemployment, inexperience with parenting, and physical insecurity as the primary obstacles preventing them from being supportive parents.

I’m not going to be one of those people. I’m not going to contribute to more f---ed up kids. (Bella, 24 year-old woman)

The decision to terminate

As participants discussed past, present, and future trajectories, we were able to identify a crucial branching point in their decision-making. For eight pregnancies (involving four female and three male participants) that were voluntarily terminated, the common theme was the incompatibility of their current lifestyle with the responsibility of raising a child. These women and men cited their young age, nomadic lifestyle, and heavy drug and alcohol use as destructive for a child. Jessica, a 23 year-old woman who had just recently arrived in Berkeley on a cross-country freight train, framed her decision to terminate her pregnancy as the least harmful solution for herself, her partner, and their unborn progeny.

I’m very selfish. I don’t want to give up my lifestyle. I feel like I wouldn’t be a good mother and I don’t want to mess up some little kid.

Ignore it and it will go away

Another strategy pursued by women who did not want to parent was to adopt, in the words of one of the women, an “ignore it and it will go away” attitude toward the pregnancy. Lisa (23 years old), Ashley (18 years old) and Carrie (19 years old), the three young women who took this approach, all acknowledged very transient lives with heavy and frequent drug and alcohol use. During their pregnancies, they hoped that intensifying substance abuse would precipitate a miscarriage.

I think [pregnancy] happens to a lot of girls but they don’t know what to do so they kind of ignore it and then it gets really f---ed up. That’s pretty much what I was doing and I think I just had in the back of my mind that I just got pregnant so if I like was drinking and living my lifestyle, maybe, I would have a miscarriage. (Lisa, 23 year-old woman)

The enormity of the situation appeared beyond these women’s ability to cope. Lisa and Ashley did indeed miscarry and Carrie eventually chose to terminate her pregnancy. She considered her heavy drug use to be proof that she was not ready to parent:

It probably [would have been better] if I had just laid off the drugs but I didn’t do that. And I feel bad about it because it proves that I wasn’t ready to have a kid because I wasn’t even taking care of it. (Carrie, 19 year-old woman)

Pregnancy narratives: Pregnancy as catalyst for personal transformation

The majority of participants chose to continue their pregnancies and hoped they would become stable parents. Many viewed the pregnancy as a catalyst for transforming their lives and overcoming past traumas:

My biggest fear was that I would be even halfway as evil to my kids as my parents were to me. . . . We were convincing each other like, ‘No you’d make a good parent.’ And for me it took meeting my little sister again and her telling me, ‘Look, you took care of me when I was a little baby and Dad was evil and Mom was on drugs. And you came to the house even when you ran away and snuck in during the day and cooked for me and taught me to read.’ (Frank, 30 year-old man)

Many participants yearned to find evidence of their capacity to be good parents. Often they convinced themselves of their potential parenting skills by adhering to an optimistic belief that despite their currently unstable living conditions, the future would offer new opportunities. By providing a better childhood for their future children than those they had experienced, many of the homeless youth who chose to attempt to become parents hoped to redeem their own troubled family past. Lily, a 26 year-old woman who at the time of the study was pregnant for the fourth time, framed her current pregnancy as a means of redemption and a way to reclaim previous unsuccessful attempts to be a good parent:

I’m going to have an amazing childhood start for this child. It’s going to be a wonderful process for me. . . . It’s kind of like having your childhood handed back to you. There’s responsibilities but then you also get so much amazing stuff along with it.

In assessing their ability to be good parents, most of the homeless youths recognized that they needed to drastically change their living situations—in their words, to “get my sh-t together” and obtain jobs, begin drug treatment, and access mental health services. For many fathers, including Dexter, a 24 year-old man who had been on the streets ever since leaving foster care at 18 years of age, accepting the responsibility of parenthood was the first time that he seriously contemplated leaving homelessness:

[My daughter] is my foot when I kick myself in the ass. Many people will kick you in the ass and try to get you together but you never really start knowing until you actually kick yourself in the ass . . . I gotta get my sh-t together. Can’t be a street kid forever. I’m a father now.

Pregnancy narratives: Interacting with services to implement decisions

Given their indigent status, all the participants sought public medical and social services to realize their pregnancy decisions, but with varying degrees of success.

Abortion services

The eight women who chose to terminate their pregnancies viewed abortion services as generally available and supportive. Local drop-in services for homeless youth were praised for being particularly helpful in allowing them to locate appropriate subsidized services. No participants reported that they were unable to access an abortion because of financial constraints. This finding may be locale-specific, however, as suggested by the routine circulation of knowledge about home remedies for pregnancy termination. For example, Adrienne, a 24 year-old woman who had had four abortions in Northern California, described alternative, risky ways of aborting, which had been recommended by traveling companions who had confronted unwanted pregnancies in other regions of the United States where subsidized abortion services are less accessible or non-existent:

Sometimes if you make a tampon out of parsley that will bring on bleeding. Large doses of pure vitamin C help a lot. There’s a thing you can do with Pennyroyal and Blue and Black Cohosh, but I don’t really like to recommend that because it’s really toxic on your body.

Accessing resources and services for parenting

Youth who chose to re-enter the mainstream experienced significant barriers to doing so. The most notable obstacle they reported explicitly was distrust of institutions and fear that clinical and social service providers would immediately report them to Child Protective Services (CPS). While homeless youth claimed to recognize that they would have to leave homelessness to be good parents, they valued their counter-cultural identities and self-consciously resisted incorporation into mainstream housed lifestyles. For example, Freddie, a 36 year-old man who had been homeless for 20 years decided to strive to become a responsible father when his 22 year-old partner Samantha became pregnant. His commitment to change, however, was charged with fear of punitive repression from social services, which he identifies as arbitrarily persecuting his goal to be a good parent:

You can’t get all excited when you’ve got worries and things you’ve got to take care of . . . like making sure they don’t abduct your children if you don’t live the way they want you to.

All the young women attended prenatal visits alone because their partner had to remain outside the clinic or in their camp to guard their belongings and pets. Although eventually all the women who chose to keep their children attended prenatal care, several women stated that they delayed seeking clinical services because of the negative experiences of other homeless youth who lost custody of their newborns. Samantha, Freddie’s 22 year-old “street wife” who had lived in Berkeley for three years, postponed accessing prenatal care until late in her second trimester in order to “fly under the radar” of CPS:

I was afraid [the clinic] would find out about me being pregnant and try to take away my baby, just like they do to everyone who’s been homeless for any time during their pregnancy.

In choosing to become parents, participants felt that they faced a frightening ultimatum—“Get your sh-t together” or have your baby taken from you and placed in foster care. The root of this fear was often their traumatic experiences as children in foster care.

I don’t want my daughter to go to foster care even for a day . . . . When I was a kid, you never knew when the stranger who was driving by was going to call the police and get your parents arrested. And I’d been taken away when I was a little kid and I hated that. That was the worst thing that ever happened to me . . . I’d been through a lot of abuse but that was nothing compared to having my family taken away from me. (Gena, 23 year-old woman)

All of the youth cited affordable housing as the most crucial resource needed to avoid losing custody of children. Nonetheless, during the years we conducted research, Berkeley had no subsidized housing facilities for homeless expectant couples.

And what is up with the city not having housing for pregnant women with a father? Am I supposed to leave the father, have a dysfunctional family just because you don’t want to give me a house? (Samantha, 22 year-old woman)

The available housing options were women-only shelters generally located in poor neighborhoods where the majority of clientele was African American. These homeless youths described ethnic and cultural conflict at the shelters.

I’m not going to go there. I’m the only White girl there and people just harass me because I have blue hair. I don’t want my baby in that kind of environment. I got into two fights the last time I was there. (Lily, 26 year-old woman)

Men, more frequently than women, discussed the lack of vocational training services to facilitate their entry into the job market. Most of the men did not accompany their partners to appointments with social services because they felt it would be a waste of time since programs generally provide money only to single homeless mothers.

[Services] seem biased. Only moms. Dads don’t mean sh-t. Moms with dad don’t get anything. (Freddie, 36 year-old man)

Contacting family in order to leave street life

At the conclusion of this study, only three couples managed to maintain custody of their children. In each of these cases, the mother was able to reunite with her family of origin. All had been estranged from their birth families for many years because of histories of abuse and/or neglect. Forgiveness for the past and hope for the next generation were crucial to enabling this reconciliation.

[The relationship with my mother] has been on-again-off-again. I feel much safer when I’m not around her. . . . But having had all that experience with [Child Protective Services] maybe [my mother] just wanted to avert the same thing from happening to me because I’d been the kid who was put in the foster home. . . . Maybe she’s trying to set the past right . . . and she actually did. I was completely amazed at the difference the time had taken. (Lily, 26 year-old woman)

In the twelve cases in which youth lost custody of their newborns, the youth had no access to support from parents or other kin. Public services provided insufficient resources for them to become stable parents without additional external help. Several youth were categorically unwilling to return to abusive homes. Others reported that their parents would not allow them to return home. For example, Maddie’s family rejected her request for support, citing her partner Rob’s mental illness and substance abuse. Maddie and Rob’s situation is one case in which the youth involved recognized that mental illness and drug abuse were significant and appropriate factors in the decision of CPS to take away their children.

Eventually I need get some mental health care so I can keep the job, house, and get the kids back eventually and grow old with my husband. Those are the goals. They’re long-term goals for me. I have to figure out how to do that though. (Maddie, 23 year-old woman)

Nevertheless, this couple deeply resented the fact that the involuntary removal of their child was justified by their refusal/inability to change their lifestyle. They adhered to a utopian vision of their place in the modern world as homeless nomads.

You should not necessarily have to have a house to be able to have a child. Three or four centuries ago people were living in tents with their children and that was fine as long as you keep them fed and warm. Having a roof and walls should not be mandatory. I think they should make a natural habitat for humans where I can raise my kids outside. (Rob, 25 year-old man)

Pregnancy narratives—Cycle of loss

Four women and two men had experienced multiple pregnancies and multiple involuntarily removals of their children. The impact of repeatedly losing custody was profound, and they expressed prolonged sadness and grief. May of them reported taking refuge in substance abuse in response to their loss.

I started doing speed when I wasn’t living with my daughter anymore. (Andromeda, 24 year-old woman)

Maddie and Rob, who had lost three children between them, conceived of themselves as victims of repressive services, yet they continued to think that their next pregnancy represented a new opportunity.

Have a baby, don’t have a baby. Maybe they’ll let us keep this one. (Maddie, 23 year-old woman)

Rob retreated into a fatalistic anticipation of death and blamed social services for his lack of motivation.

[Having my children taken] just destroyed my want, my desire . . . I have no more drive left. I don’t care to move on. I’ll be dead in five years anyway. (Rob, 25 year-old man)

Discussion

Central to understanding the common thread that weaves these 26 pregnancy narratives together is the fact that pregnancy is a major destabilizing event in the lives of homeless youth. Pregnancy narratives bring into the foreground hope for change, present poverty, and past traumas. However, many of these narratives end in further cycles of abuse and avoidance of services. Our participants conceptualized pregnancy as a crossroads in their lives. Those who chose to attempt to become parents were convinced they had the personal ability to transform their lives despite their lack of access to material resources, including housing, stable income, and health services, such as mental health and substance abuse treatment. Young homeless men and women described their partners as the most important person in their pregnancy decision-making process.

Nevertheless, men were largely invisible to and excluded from services. Furthermore, in most cases, the relationship within which decision-making was taking place was characterized by emotional, verbal, or physical abuse. In their deliberations, all of our participants described homelessness and survival on the street, and often mentioned drug use and mental illness as being incompatible with pregnancy and parenthood. In some cases, young women found their situation so overwhelming they attempted to ignore the pregnancy by increasing their use of drugs and alcohol. Of the eight women who chose to terminate their pregnancies, all reported that they found abortion services accessible in Berkeley. Several had purposefully traveled to Northern California from areas with less access to termination services. In contrast, most youth who chose to become parents avoided or postponed seeking services because they feared contact would precipitate the removal of their child by the authorities. In our sample of 15 pregnancies carried to term in which youth expressed the desire to become parents, only the three couples who were able to reunite with families of origin were able to maintain custody of their children. In the remaining 12 cases, the trauma of losing a child and the dashing of their unrealized hopes for changing their lives resulted a cycle of loss, including depression, drug use, and further avoidance of social and health services.

Based on our documentation of our participants’ collective experience, we propose that pregnancy represents a liminal life crisis in which many youth unrealistically seek to overcome challenges that have plagued most of their lives through sheer individual will power and idealism. In describing why they chose to terminate or to parent, homeless youth claimed to have control over their own destinies and vowed not to repeat the traumas they suffered at the hands of their families of origin and the foster care system. Indeed, the homeless youth in this study embraced an autonomous identity and claimed that they were and had always been in charge of their destinies.

Pregnancy represents a rare strategic opportunity for services to connect with especially vulnerable individuals at a moment when they yearn to change their lives.30 Consistent with Auerswald and Eyre’s model of the life cycle of youth homelessness, pregnancy is an example of a crisis, or episode of disequilibrium, that threatens their ability to survive on the street and calls into question their desire to continue to live on the street.22 Prior research also shows that some youths in disequilibrium increase their risky behaviors, as in the case of the three women who purposefully increased drug and alcohol use to precipitate a miscarriage.31 Those youths who chose to become parents and extricate themselves from the street or who chose to terminate their pregnancies, in contrast, increased their use of services dramatically.32 Nevertheless, like most homeless youth in crisis, our participants did not have the skills, support, and most importantly the resources to leave homelessness, even when they were highly motivated.

While youth were often convinced that they could enact their decisions independently, the ability to change their lives was profoundly affected by the structural constraints of poverty, inadequate services, and inability to access resources through other means. The homeless youth in our study, like the homeless adults described in other studies, identify fear of losing custody of their children as a primary barrier to accessing prenatal care.33,34,35 Like other marginalized women, our female participants were simultaneously fearful of “baby-snatchers” and looking for help from the social workers, doctors, nurses, and other providers who work with this population. Our youth recognize the benefits of health care and, in most cases, they realize that accessing public resources is their only viable means for extricating themselves from homelessness. They are also acutely conscious that accessing care increases the chances that their child will be removed from their care. For many of them, especially those who grew up in foster care themselves, the risks of accessing these services may not outweigh the benefits. Service providers must directly and honestly reveal to their clients/patients the mandatory reporting regulations to which they are subject as well as the detailed consequences of a report to CPS, because the primary obstacle to accessing prenatal services is fear of losing custody of one’s newborn.

Our finding that homeless youth engage in their decision-making process as a couple when faced with a pregnancy has important implications for professionals working directly with pregnant homeless youth. Providers should inquire about the youth’s relationship with her partner, explore issues of safety, provide support for decision-making and, when appropriate, include the male partner in discussions and medical and/or social services appointments. Providers working with young, pregnant homeless women may want to inquire regarding the woman’s relationship with the father of her child and how this relationship may be positively and negatively affecting her decision-making. Providers working with couples or men alone may consider facilitating discussions within the couple about the stresses of a pregnancy and decision-making and provide support and resources for both men and women during this time.

For youth choosing to terminate their pregnancies, our study participants were satisfied with the abortion services they encountered and some had traveled specifically to Berkeley for abortion services. Many of our participants described other women using alternative, and potentially life-threatening, methods to induce abortions when services were not available, such herbal therapies, increasing drug use, or physical violence directed at the abdomen. This phenomenon has also been described by Ensign.36 These data point to the need for increased access to reproductive health care, including accessible and free abortion services. Free short and long-term contraception and counseling should be made easily available to young homeless women and men to prevent unintended pregnancies. Safe, free abortion services must be guaranteed to prevent life-threatening self-induced abortions. When delivering non-judgmental, honest, and supportive counseling on termination options, a service provider must address the fact that a pregnant woman’s decision-making process at this stage often occurs in the context of an unstable, violence-prone, homeless male partner, even if that partner is not visible to the service provider. Additionally, the same panel of services that are offered to women who choose to become parents must be made available to women and men who choose to terminate their pregnancies or who lose custody of their newborns involuntarily.

Regardless of the outcomes, all the decisions made by our participants were framed by structural constraints. The same factors that lead to homelessness and to pregnancy—including poverty, lack of access to contraception, abusive relationships, and problematic relationships with families-of-origin—also lead to challenges in decision-making, and in becoming a parent. Just as those factors are initially out of youths’ control, they are out of their control in the context of a pregnancy. Among those couples choosing to become parents, we documented only three cases out of 15 in which youth were able maintain custody. The crucial factor in these cases was the ability of the mothers to turn to their families for housing. In all of the cases in which custody was lost, the parents were unable to access familial support and were unable to obtain housing through social services. For several couples, women were unwilling to leave their male partners in order to obtain housing. Without additional subsidized and supportive housing resources, the majority of youth are doomed to fail in the attempt to leave homelessness. Access to housing for pregnant women along the housing first model pioneered by San Francisco and several other cities37,38,39 must be designed with provisions regarding fathers, including the father as a member of the household when appropriate.

Although homeless youth have experienced an great deal of stress at a very early age, they are often resilient, harnessing a wide variety of resources, including social services, the homeless youth community and their personal strength, to survive on the streets.40,41 Research has demonstrated that the pregnancy decision-making process is a life-altering moment for many young women42 and men43 and that pregnancy care providers can be important gatekeepers to information and services, particularly among poor and marginalized women.35,44 However, we know little regarding how homeless youth, a population at high risk of pregnancy but notoriously wary of authority and institutions, make decisions and act on them. The current organization of services often results in counterproductive alienation from and hostility to services (and in some cases cycles of even more destructive self-destructive behavior) because of the frequent emphasis on custody over and above supporting youth in obtaining the housing, employment, and mental health and drug treatment needed to maintain custody. Service providers must recognize the structural forces that stand in the way of youth’s ability to become stable parents, including the need for significant outside resources from kin or from services. Otherwise, a cycle of individual blame may be reinitiated that could exacerbate self-destructive behaviors and lead to future avoidance of and hostility to services. Wrap-around services in youth-friendly institutional environments are needed to provide a single point of contact for accessing reproductive health services, housing, referrals to substance abuse treatment, mental health care, vocational training, income subsidy programs, parenting courses, and assistance with integration into supportive social networks.

There are several limitations to the generalizability of our results to other homeless populations. Berkeley is a unique environment with tolerant policies towards the homeless population. Northern California is also well-known for the visibility and prevalence of counter-cultural opposition identities among White homeless youth, and the participants in this study may not be representative of homeless youth in other areas. In addition, the Northern California Bay Area offers a variety of social and health services specifically catering to the needs of homeless youth, resources often not available in other locations. Furthermore, given our limited number of youth participants, almost all of whom were White, these results may not be applicable to other homeless youth, and specifically not to those from ethnic minority populations and gay youth (two subgroups known to have high rates of pregnancy).45,46 Finally, recall bias introduced in discussing of past pregnancies as well as bias resulting from interviewing couples together may have influenced the ways that youth chose to portray their pregnancies and decision-making process.

More research is needed to understand better the window of opportunity that pregnancy presents, regardless of outcome, to engage youth at a time when they strongly desire support. Such research could inform the design of wrap-around services that meet their needs at this vulnerable time. A deeper understanding of the complex process of pregnancy decision-making could also inform the approach to other crises in the homeless youth life cycle, such as drug overdose or mental health crisis, when youth may be motivated to engage with social and health services. Our data indicate that for homeless youth pregnancy can be a powerful motivator for change and self-evaluation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a UC, Berkeley–UCSF Joint Medical Program research grant. Background information was drawn from NIH grant DA 10164. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2006 American Public Health Association Conference. We thank Karen Sokal-Gutierrez for her mentorship and help with early versions of this paper. We also thank Emily Ozer and Jane Mauldon for their help in the development of this study. This endeavor would not have been possible without the support of the Alan Steinbach and the Suitcase Youth Clinic volunteers, for which we are grateful.

Contributor Information

Marcela Smid, Graduate of the UCSF–UC Berkeley Joint Medical Program and is currently a resident in obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago. She conducts qualitative research on understanding barriers to pregnancy care and family planning services among homeless and marginalized populations.

Philippe Bourgois, Richard Perry University Professor of Anthropology and of Family Medicine and Community Health) has been funded since 1989 by the National Institutes of Health to conduct ethnographic research on the risk environments faced by homeless and street-based drug-using populations. He just published Righteous Dopefiend with the University of California Press.

Colette L. Auerswald, (UCSF Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Director of the Master’s Program of the UCSF–UC Berkeley Joint Medical Program) conducts ethnographic and epidemiological studies of the effect of the social and cultural environment on the health of homeless and marginalized youth populations in the San Francisco Bay Area and in Kisumu, Kenya.

Notes

- 1.Greene J, Ringwalt C. Pregnancy among three national samples of runaway and homeless youth. J Adolesc Health. 1998 Dec;23(6):370–377. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Nowhere to grow: homeless and runaway adolescent and the families. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saewyc EM. Influential life contexts and environment for out-of-home pregnant adolescents. J Holist Nurs. 2003 Dec;21(4):343–367. doi: 10.1177/0898010103258607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Passaro J. The unequal homeless: men on the streets women in their place. New York, NY: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grozka PA. Homeless parents’ perceptions of parenting stress. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 1999 Jan–Mar;12(1):7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.1999.tb00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourgois P, Schonberg J. California Series in Public Anthropology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2009. Righteous dopefiend. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gloeckner P. The diary of a teenage girl: an account in words and pictures. Berkeley, CA: Frog Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz PD, Lindsey EW, Jarvis S, et al. How runaway and homeless youth navigate troubled waters: the role of formal and informal helpers. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2000 Oct 30;17(5):1573–2797. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry PJ, Ensign J, Lippek SH. Embracing street culture: fitting health care into the lives of street youth. J Transcult Nurs. 2002 Apr;13(2):145–152. doi: 10.1177/104365960201300208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Ackley KA. Families of homeless and runaway adolescents: a comparison of parent/caretaker and adolescent perspectives of parenting, family violence and adolescent conflict. Child Abuse Negl. 1997 Jun;21(6):517–528. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyler KA, Cauce AM. Perpetrators of early physical and sexual abuse among homeless and runaway adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2002 Dec;26(12):1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00413-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson MJ, Toro PA. Homeless youth: research, intervention and policy. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ringwalt CL, Greene JM, Robertson MJ. Familial backgrounds and risk behaviors of youth with thrownaway experiences. J Adolesc. 1998 Jun;21(3):241–252. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meadows-Oliver M. Homeless adolescent mothers: a metasynthesis of their life experiences. J Pediatr Nurs. 2006 Oct;21(5):340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haley N, Roy E, Leclerc P, et al. Characteristics of adolescent street youth with a history of pregnancy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004 Oct;17(5):313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene JM, Ennett ST, Ringwalt CL. Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runway and homeless youth. Am J Public Health. 1999 Sep;89(9):1406–1409. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wenzel SL, Leake BD, Andersen RM, et al. Utilization of birth control services among homeless women. Am Behav Sci. 2001;45(1):14–34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ensign J, Panke A. Barrier and bridges to care: voices of homeless female adolescents youth in Seattle, Washington, USA. J Adv Nurs. 2002 Jan;37(2):166–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saewyc EM, Magee LL, Pettingell SE. Teenage pregnancy and associated risk behaviors among sexually abused adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004 May–Jun;36(3):98–105. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.98.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourgois P, Prince B, Moss A. The everyday violence of Hepatitis C among young women who inject drugs in San Francisco. Hum Organ. 2004 Sep;63(3):253–264. doi: 10.17730/humo.63.3.h1phxbhrb7m4mlv0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Homeless youth. Berkeley, CA: Planning and Development Department; 1996. City of Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auerswald CL, Eyre SL. Youth homelessness in San Francisco: a life cycle approach. Soc Sci Med. 2002 May;54(10):1497–1512. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez M. Nobody’s child. San Francisco Chronicle. 1998 Nov 17; Sect A1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strickland E. Whose Haight? SF Weekly. 2006 Sep 20;:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Speiglman R, Norris JC. Alameda county shelter and services survey county report. Oakland, CA: Public Health Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 2. QSR International Pty. Ltd. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bourgois P, Martinez A, Kral A, et al. Reinterpreting ethnic patterns among white and African American men who inject heroin: a social science of medicine approach. PLoS Med. 2006 Oct;3(10):e452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hickler B, Auerswald CL. The worlds of homeless white and African American youth in San Francisco, California: a cultural epidemiological comparison. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Mar;68(5):824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.030. Epub 2009 Jan 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rew L, Horner SD. Personal strengths of homeless adolescents living in a high risk environment. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2003 Apr–Jun;26(2):90–101. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200304000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parriott A, Auerswald C. Predictors of injection drug use initiation in a street-recruited sample of San Francisco street youth. Substance Abuse and Misuse. (In press.) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlson JL, Sugano E, Millstein SG, et al. Service utilization and the life cycle of youth homelessness. J Adolesc Health. 2006 May;38(5):624–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloom KC, Bednarzyk MS, Devitt DL, et al. Barriers to prenatal care for homeless pregnant women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004 Jul–Aug;33(4):428–435. doi: 10.1177/0884217504266775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinreb L, Browne A, Berson JD. Services for homeless pregnant women: lessons from the field. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1995 Oct;65(4):492–501. doi: 10.1037/h0079677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy S, Rosembaum M. Pregnant women on drugs: combating stereotypes and stigma. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ensign J. Reproductive health of homeless adolescent women in Seattle. 2–3. Vol. 31. Washington, USA: Women Health; 2000. pp. 133–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004 Apr;94(4):651–656. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davidson NM. ‘Housing first’ for the chronically homeless: challenges of a new service model. J Affordable Housing & Community Development Law. 2006 Apr 24;15:125. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gladwell M. Million-dollar murray. The New Yorker. 2006 Feb 13;:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rew L, Horner SD. Youth Resilience Framework for reducing health-risk behaviors in adolescents. J Pediatr Nurs. 2003 Dec;18(6):379–388. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rew L, Taylor-Seehafer M, Thomas NY, et al. Correlates of resilience in homeless adolescents. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33(1):33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanna B. Negotiating motherhood: the struggles of teenage mothers. J Adv Nurs. 2001 May;34(4):456–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holmberg LI, Wahlberg V. The process of decision-making on abortion: a grounded theory study of young men in Sweden. J Adolesc Health. 2000 Mar;26(3):230–234. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy V. Protective steering: a grounded theory study of the processes by which midwives facilitate informed choices during pregnancy. J Adv Nurs. 1999 Jan;29(1):104–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rew L, Whittaker TA, Taylor-Seehafer MA, et al. Sexual health risks and protective resources in gay, lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual homeless youth. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2005 Jan–Mar;10(1):11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1088-145x.2005.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson SJ, Bender KA, Lewis CM, et al. Runaway and pregnant: risk factors associated with pregnancy in a national sample of runaway/homeless adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2008 Aug;43(2):125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.015. Epub 2008 Apr 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]