Abstract

Identification of gene function is important not only for basic research but also for applied science, especially with regard to improvements in crop production. For rapid and efficient elucidation of useful traits, we developed a system named FOX hunting (Full-length cDNA Over-eXpressor gene hunting) using full-length cDNAs (fl-cDNAs). A heterologous expression approach provides a solution for the high-throughput characterization of gene functions in agricultural plant species. Since fl-cDNAs contain all the information of functional mRNAs and proteins, we introduced rice fl-cDNAs into Arabidopsis plants for systematic gain-of-function mutation. We generated >30,000 independent Arabidopsis transgenic lines expressing rice fl-cDNAs (rice FOX Arabidopsis mutant lines). These rice FOX Arabidopsis lines were screened systematically for various criteria such as morphology, photosynthesis, UV resistance, element composition, plant hormone profile, metabolite profile/fingerprinting, bacterial resistance, and heat and salt tolerance. The information obtained from these screenings was compiled into a database named ‘RiceFOX’. This database contains around 18,000 records of rice FOX Arabidopsis lines and allows users to search against all the observed results, ranging from morphological to invisible traits. The number of searchable items is approximately 100; moreover, the rice FOX Arabidopsis lines can be searched by rice and Arabidopsis gene/protein identifiers, sequence similarity to the introduced rice fl-cDNA and traits. The RiceFOX database is available at http://ricefox.psc.riken.jp/.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, Full-length cDNA, Gene function, Oryza sativa, Trait, Transgenic plant

Introduction

The generation of loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutant resources is one of the effective approaches for the identification of plant gene functions (Kuromori et al. 2009). For loss-of-function mutant analysis, many loss-of-function mutants have been generated by T-DNA and Ds-transposon insertions in Arabidopsis thaliana (Springer et al. 1995, Martienssen 1998, Ito et al. 2002, Alonso et al. 2003, Kuromori et al. 2004). Similarly, in rice, knockout mutants have been prepared by Tos17 retrotransposon and Ds-transposon insertions (Hirochika et al. 2004, Kolesnik et al. 2004, van Enckevort et al. 2005). These mutant resources are widely used for the analysis of gene functions disrupted by the insertion elements. With regard to gain-of-function approaches, several procedures have also been applied to investigate gene function in plants. For example, the activation tagging method is based on the random insertion of cauliflower mosaic virus 35S (CaMV 35S) transcriptional enhancers into the plant genome. This method was first applied to Arabidopsis, and allowed us to isolate mutants with severe morphological traits (Weigel et al. 2000, Li et al. 2001, Nakazawa et al. 2003, Yoshizumi et al. 2006). Likewise, the method was applied to rice (Hsing et al. 2007). However, the CaMV 35S enhancer can affect gene expression up to several kilobases from the insertion site (Hsing et al. 2007), sometimes resulting in difficulties in the identification of genes responsible for the observed mutant traits.

Therefore, in order to improve the identification of genes responsible for the observed mutant traits, we have developed transgenic Arabidopsis lines overexpressing full-length cDNAs (fl-cDNAs). These transgenic lines, named FOX (full-length cDNA Over-eXpressor gene) Arabidopsis lines, express 1–2 Arabidopsis fl-cDNAs under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter (Ichikawa et al. 2006). The FOX hunting system is unique in that only fl-cDNAs are required for the functional analysis of genes, and has an advantage for plants that have large genomes or a long life cycle. Advances in methods for transforming Arabidopsis without the need for tissue culture have shortened the time required for gene function analysis (Clough and Bent 1998). We obtained various morphological and physiological mutants from >30,000 rice FOX Arabidopsis mutant lines using rice fl-length cDNAs (Kondou et al. 2009).

A large number of mutants have been generated and analyzed using loss- or gain-of-function approaches. Informational resources from these studies have been organized into databases and published on the Internet. These databases contain a large volume of information on mutants (Li et al. 2003, Samson et al. 2004, Sakurai et al. 2005, Zhang et al. 2006, Dalmais et al. 2008, Larmande et al. 2008). However, most of the records in these databases include few paired descriptions of genomic information (e.g. tag insertion position on the genome and introduced gene) and traits corresponding to each mutant (Kuromori et al. 2006). Here, we describe our novel database, RiceFOX, which aims to identify effectively the function of each gene. Moreover, this database has useful search functions, including the ability to refer to the introduced rice fl-cDNA in addition to the broad range of morphological and invisible traits. RiceFOX access is available via the web interface at http://ricefox.psc.riken.jp/.

Database contents

Rice FOX Arabidopsis mutant phenotypes were categorized into 19 primary aspects that consist of eight morphological and 11 invisible aspects (Table 1). The RiceFOX database houses wide-ranging information on 17,985 rice FOX Arabidopsis lines. Most of the mutant line entries provide information on the introduced rice fl-cDNA and pictures related to each morphological trait. The overview of the records in RiceFOX is summarized by screening categories in Table 1. The briefs of those screening categories are described below. Contents on the RiceFOX database are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.1 License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is cited properly.

Table 1.

Overview of the entries in the RiceFOX database summarized by screening categories

| Screening categories | No. of lines |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened | Objective | |||

| Morphological trait | Adult plant | Growth | 256 | 33,623 |

| Plant height | 655 | |||

| Flowering | 122 | |||

| Root | Number | 75 | ||

| Others | 6 | |||

| Rosette leaf | Shape | 1,603 | ||

| Color | 651 | |||

| Number | 537 | |||

| Others | 883 | |||

| Cauline leaf | Shape | 406 | ||

| Color | 102 | |||

| Number | 113 | |||

| Others | 239 | |||

| Stem | Shape | 679 | ||

| Color | 66 | |||

| Number | 83 | |||

| Others | 766 | |||

| Flower | Shape | 68 | ||

| Others | 87 | |||

| Silique | Shape | 280 | ||

| Others | 127 | |||

| Seed | Shape | 3,014 | ||

| Color | 480 | |||

| Number | 330 | |||

| Invisible trait | Plant hormones | 73 | 175 | |

| Elements | 283 | 9,869 | ||

| Pigments | 35 | 4,302 | ||

| Photosynthesis | Chl fluorescence | 129 | 9,947 | |

| High light stress | 66 | 4,570 | ||

| UV signaling | 51 | 7,352 | ||

| Metabolite | GC-TOF/MS profile | 13 | 350 | |

| FT-NIR fingerprint | 23 | 3,003 | ||

| Salicylic acid sensitivity | 53 | 21,200 | ||

| Resistance to bacterial pathogen | 70 | 20,000 | ||

| High-salinity tolerance | 46 | 21,048 | ||

| Thermotolerance | 3 | 20,184 | ||

| UV stress tolerance | 43 | 7,199 | ||

Morphological traits

Visible traits in the T1 generation can be observed in parallel with producing lines, because traits of the rice FOX Arabidopsis lines are basically dominant (Ichikawa et al. 2006). With regard to these morphological traits, we focused on the whole plant, root, rosette and cauline leaf, stem, flower, silique and seed, and described their features such as speed of growth, shape, color, number, and so on via our own description. For example, the items for rosette leaf were ‘large’, ‘small’, long’, ‘short’, ‘wide’, ‘narrow’, ‘epinastic’, ‘hyponastic’ and ‘spiral’ for shape; ‘dark’, ‘pale’ and ‘variegated’ for color; and ‘many’ and ‘few’ for number. The traits of lines showing abnormal morphology in the T1 generation were checked in the T2 generation and described in the database. Additionally, for the seed trait, several numerical data such as diameter and seed color code were included in the records of many rice FOX Arabidopsis lines in the T2 generation.

Plant hormone profiles

Plant hormones play important roles as signaling molecules in the regulation of almost all phases of plant development, from seed germination to senescence. For instance, cytokinins are involved in the regulation of leaf senescence, apical dominance, shoot development and root–shoot balance; auxins in apical dominance, phyllotaxis and root development; ABA in seed dormancy and stress response; and gibberellins in seed germination and leaf development (Davies 2004). The contents of these plant hormones were analyzed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (Kojima et al. 2009) and included in the RiceFOX database.

Element accumulation

Elements are essential not just for plant growth, but also for human nutrition and health. We tried to isolate rice genes that cause higher accumulation of elements in plants to support crop breeding for bioremediation (Guerinot and Salt 2001) and to improve human health in developing countries (Daar et al. 2002). On this basis, a system was developed to measure ratios of any number of elements in plants. We simultaneously measured the ratios of potassium, calcium, iron, zinc, manganese, magnesium, sulfur and silicon in rice FOX Arabidopsis lines in the T1 generation.

Pigment accumulation

It is known that pigments function as protectors against high light (Steyn et al. 2002) and UV irradiation in plants (Jin et al. 2000). Additionally, they contribute to the taste and color of fruits, vegetables, grains and flowers. Thus, biotechnologies for the control of these compounds offer potential benefits. In this study, we measured the optical density of a solution extracted from the rosette leaves of rice FOX Arabidopsis lines at wavelengths of 305 and 530 nm in order to detect accumulation of UV-absorbing compounds (Mazza et al. 2000) and anthocyanins (Hodges et al. 1999), respectively.

Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is one of the most important determinants of plant productivity. Chl fluorescence has been widely used to identify photosynthesis mutants because it reflects the state of photosynthetic electron transport (Baker 2008). We used Chl fluorescence imaging to isolate photosynthesis-related mutants from rice FOX Arabidopsis lines. The time course of changes in Chl fluorescence intensity and photosynthetic parameters of rice FOX Arabidopsis lines were compared with those of the wild type.

Light is critical for the growth and development of plants. However, too much light is known to result in photo-oxidative damage (Asada 1999). Although the response of the photosynthetic apparatus to high irradiation must have an underlying regulatory mechanism, little is known about this mechanism. To isolate high light-tolerant rice FOX Arabidopsis lines, Chl fluorescence was measured after high light treatment. One of the photosynthetic parameters, maximal quantum yield (Fv/Fm), was used as an indicator of photo-oxidative damage.

UV signaling

In plants, UV light damages DNA and the photosynthetic machinery and generates reactive oxygen species that damage macromolecules. However, low UV-B fluence rates can stimulate the transduction of signals that regulate the plant's protective response. Some of these UV-B responses are activated not by DNA damage but specifically by radiation in the UV-B range (280–320 nm), and regulate the expression of a wide range of genes (Jenkins 2009). Therefore, it is important that we understand how signal transduction leads to the regulation of the expression of genes that mediate protection against UV-B light. We tried to isolate rice genes that cause hypersensitivity to low UV-B irradiation by looking for the inhibition of hypocotyl elongation by UV-B doses below the level that triggers damage responses in plants (Suesslin and Frohnmeyer 2003).

Metabolite phenotyping using two different metabolomics approaches

Metabolomics allows comprehensive phenotyping, filling a niche between systems biology and functional genomics. It thus contributes greatly to integrated functional genomics. We applied two different metabolomics approaches—metabolite profiling and metabolite fingerprinting—to screen changes in the metabolite composition of FOX Arabidopsis mutants. Metabolite profiling is one of the strategies used to study the metabolome. This approach can be used for in-depth investigation of metabolite responses. Gas chromatography–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOF/MS) is one of the most widely used techniques and a key technology in metabolite profiling. We performed GC-TOF/MS analysis using aerial parts of rice FOX Arabidopsis mutants (Albinsky et al. 2010).

Metabolite fingerprinting is used in metabolomics because it enables rapid, high-throughput analysis and provides information from the spectra of total metabolite compositions. Fourier transform near-infrared (FT-NIR) spectroscopy has great potential for metabolite fingerprinting because it is simple to operate, and various types of samples (liquid, solid and powder) can be analyzed non-destructively. In addition, the spectral traits can be systematically extracted by multivariate statistical analysis. Therefore, we used FT-NIR for metabolic screening of rice FOX Arabidopsis mutant seeds (Suzuki et al. 2010).

Salicylic acid sensitivity

The signaling pathway mediated by salicylic acid (SA) plays a crucial role in the defense responses of plants (Durrant and Dong 2004). Rice also has the SA signaling pathway, but only a small number of regulatory components in this pathway have been identified (Takatsuji et al. 2010). To identify new components of the pathway or regulatory components that modulate the pathway in rice, we screened for SA hypersensitivity in rice FOX Arabidopsis lines. Ten T2 seeds of each FOX line were sown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium plates with 50 μM SA and grown for 12–14 d at 22°C under 16 h light and 8 h dark photoperiods. Lines that showed dwarf and white or pale green phenotypes similar to the npr1 mutant (Zhang et al. 2003) were selected as ‘SA-hypersensitive’.

Resistance to bacterial pathogen

The interaction between Arabidopsis and the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae has been used as a model for investigating the various mechanisms and processes involved in host resistance and bacterial virulence (Kim et al. 2008). The main objective of this research is to look for rice genes that confer resistance to bacterial pathogens, genes that will confer resistance to host plants in a wide variety of genera to various pathogenic organisms. The rice FOX Arabidopsis lines were screened for resistance to compatible P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000) for this purpose. Three-week-old T2 plants were inoculated with 0.5–2 × 108 cfu ml−1 of Pst DC3000 and disease symptoms were evaluated 6 d after inoculation. Wild-type plants were apparently killed by the screening condition. In contrast, the plants from some rice FOX Arabidopsis lines survived 6 d after inoculation, similar to the resistant control plants, cpr5-2 (Boch et al. 1998). These lines were estimated to be resistant. The number of lines that survived after three rounds of screening is listed in Table 1. Detailed methods and results were recently described (Dubouzet et al. 2011).

High-salinity tolerance

High salinity is one of the major extrinsic factors affecting plant growth and crop productivity. To sustain agricultural productivity and improve agricultural practices, an increase in salinity tolerance of plants is needed by either traditional breeding or genetic manipulation. We used the rice FOX Arabidopsis mutants to collect rice genes with the potential to increase salinity tolerance by molecular breeding. About 15 T2 seeds of each line were sown on 1/2 MS medium containing 1% sucrose, 0.8% agar and 150 mM NaCl, and were incubated at 22°C under continuous light for 1 week. Based on visual assessment, lines with a higher germination rate and greener cotyledons were selected (Yokotani et al. 2009).

Thermotolerance

High temperature poses a substantial constraint on the productivity and geographic range of crops, even with the highly sophisticated management systems of today's agriculture. There is a risk that increasing global temperatures will change the optimum sites and conditions for crop production and harm agriculture. We used the rice FOX Arabidopsis mutants to collect rice candidate genes related to a thermotolerant trait. About 15 T2 seedlings of each line were grown on agar medium at 22°C. A Petri dish containing 4-day-old seedlings was sealed with vinyl tape and dipped into water warmed to 42°C for 90 min. Subsequently, the Petri dish was incubated at 22°C for 10 d. Tolerance was estimated based on whether seedlings green (Yokotani et al. 2008).

UV stress tolerance and root elongation

Plants are continuously exposed to environmental stresses such as UV-B light. UV-B radiation causes growth retardation of plants by inhibiting cell proliferation. This leads to decreased productivity. Genetic manipulation could improve the UV-B tolerance of plants. Roots are essential for resource capture, plant stability and anchorage, so the enhancement of root growth should increase yield. To identify rice genes that confer resistance to UV-B or promote root growth in rice FOX Arabidopsis lines, we screened several long-root mutants from the rice FOX Arabidopsis lines using a root-bending assay (Sakamoto et al. 2003, Takahashi et al. 2005) with modifications. Seedlings were exposed to 7–8 kJ m−2 UV-B and then incubated under continuous white light for another 3 d. After incubation, lines that had roots longer than those of the wild type were selected as candidate mutant lines. Screenings were performed three times to confirm the identification of mutant lines.

Introduced rice fl-cDNAs

We generated a rice fl-cDNA expression library by using approximately 13,000 rice fl-cDNAs under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. The rice fl-cDNAs we used are a part of the rice fl-cDNA collection of the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences (NIAS) (Kikuchi et al. 2003). So far, we have sequenced 6,522 rice fl-cDNAs amplified from 14,401 rice FOX Arabidopsis lines. For the purpose of aiding the understanding of traits in Arabidopsis gene function, Arabidopsis coding sequence (CDS) information was attached to the rice cDNA sequence records, as many rice CDS are homologous to those in Arabidopsis.

Information organizing and database implementation

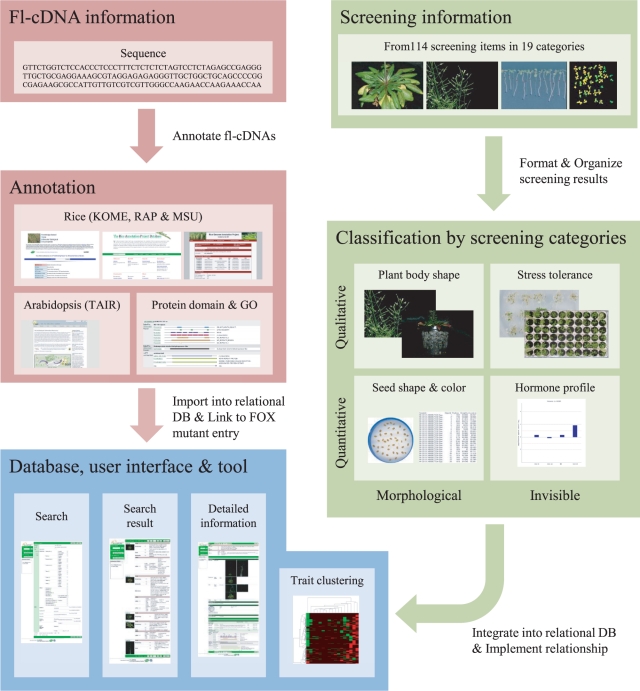

We have performed comprehensive screening of the rice FOX Arabidopsis mutant lines as described above, and a large number of the comprehensive screening records have been collected. In addition, the introduced rice fl-cDNAs in each rice FOX Arabidopsis line have been sequenced and identified. It is important to integrate the results of the various screening categories in order to analyze gene function effectively. Fig. 1 shows an overview of the RiceFOX implementation. We classified the screening categories by data type. Next, in order to import the results into a relational database, we organized and formatted the screened results of the rice FOX Arabidopsis mutant lines. With regard to specific results categories such as seed morphological screening and hormone profile, we then performed statistical analyses. Rice fl-cDNA information such as sequence, similarity-based annotation and ontology were also imported into the database. Finally, these information entries were integrated to form the searchable RiceFOX database.

Fig. 1.

Overview of workflow to organize the results of FOX mutant screening and database implementation. RiceFOX provides several ways to search the results from screening by IDs, keywords or sequence similarity.

Database access and interface

Search interface of RiceFOX

To browse housed rice FOX Arabidopsis mutant entries, RiceFOX provides a web-based search interface enabling keyword, traits, several identifiers (IDs) related to introduced cDNA function, and sequence similarity searches. RiceFOX has 19 primary and 103 secondary categories for selectable traits. Searches with keyword strings are possible with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997) definitions, as well as with IDs from databases such as original rice fl-cDNA (Yazaki et al. 2004), GenBank (Benson et al. 2010), MSU rice genome annotation release 5.0 which is previously known as the TIGR rice genome annotation (Ouyang et al. 2007), RAP-DB annotation release 2 (Tanaka et al. 2008), TAIR8 Arabidopsis locus (Swarbreck et al. 2008), InterPro release 16.2 (Hunter et al. 2009) and gene ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al. 2000) assigned in the InterProScan results. NCBI BLAST has also been implemented on RiceFOX. These search interfaces provide users with effective access to rice FOX mutant entries by using various types of queries.

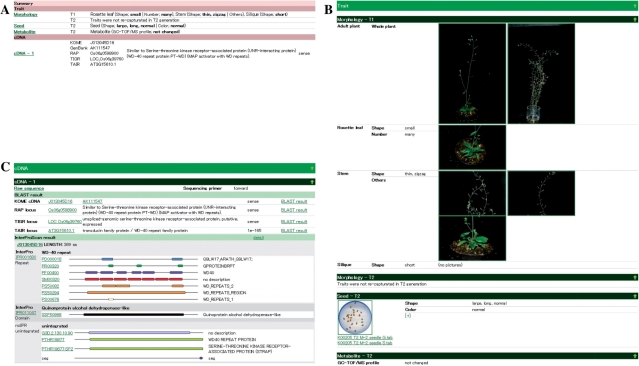

Screening result and introduced fl-cDNA annotation

Detailed information pages of each rice FOX Arabidopsis line consist of a summary, the screening result and annotation of the introduced rice fl-cDNA. First, the summary contains a text-based outline with hyperlinks to corresponding information on the upper part of the page (Fig. 2A). This summary portion allows researchers to determine the annotation status of the searched entries and the annotation most likely to be of interest, and facilitates users seeking relationship between traits and genes. Subsequently, the screening result provides pictures corresponding to each trait as well as trait information (Fig. 2B). The annotation of the introduced rice fl-cDNA is shown on the lower part of the page, and, whenever possible, links to the original data for each similar hit against RAP-DB, MSU rice genome, protein domain and GO annotation are provided to enable browsing of additional related information (Fig. 2C). For domain-based functional annotation, the fl-cDNA sequence data were submitted to a domain search using InterProScan. Users can browse each of the results of the protein domain search, along with the predicted GO classification.

Fig. 2.

Example of the detailed information for a rice FOX Arabidopsis line (K00205). (A) Summary table for a rice FOX Arabidopsis line containing the observation results and introduced rice fl-cDNA. (B) Detailed information of the observation results. (C) Annotation of the introduced rice fl-cDNA with links to the original data for each similar hit against RAP-DB and MSU rice genome annotation, and protein domains by InterPro.

Trait hierarchical cluster analysis

The trait hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) tool is a web-based application and facilitates identification of the relationships of mutant traits. In order to enable HCA by mutant trait, all screening results that the RiceFOX database contains were converted from trait vocabularies to numerical values (Supplementary Table S1). The numerically converted trait information can be applied to the HCA by optional distance and clustering methods, screening items and related genes. Therefore, this clustering tool aids the understanding of relationships among the traits of interest. The procedure is divided into two main steps. In the first step, in order to retrieve the observation records of the rice FOX Arabidopsis mutants, users select the generation (T1/T2), search condition (and/or) and screening items that are of interest. Next, in order to cluster the retrieved mutant line records in the first step, users choose the clustering method (average, single, complete, ward, mcquitty, median and centroid) and distance method (manhattan, euclidean, maximum, binary and minkowski), and then select the screening items that are to be calculated by HCA execution. Finally, users are able to obtain the trait HCA result and supplementary files for confirmation.

Conclusion

There are some databases similar to the RiceFOX database in that they contain a lot of information on mutant lines. However, RiceFOX has useful search functions, and it is possible to refer to the introduced rice fl-cDNA in addition to the morphological features of a broad range of traits and invisible traits. This is the first time such a large and comprehensive amount of data pertaining to the traits of plant mutants and their related candidate genes has been collected for reference from a single system. The database should accelerate progress in plant genomics and gene functional annotation, as well as facilitate rapid characterization of useful crop traits. For further enrichment of the information concerning gene function, we will update this database and develop new tools for the advancement of plant genomics.

The rice FOX Arabidopsis line screening is ongoing and RiceFOX will be updated as new data become available.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at PCP online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency [a Special Coordination Fund for Promoting Science and Technology].

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Satoshi Tabata (Kazusa DNA Research Institute), Yuichiro Watanabe (University of Tokyo), Kenzo Nakamura (Nagoya University) and Naoyuki Umemoto (Kirin Co. Ltd.) for their helpful discussions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CaMV

cauliflower mosaic virus

- CDS

coding sequence

- fl-cDNA

full-length cDNA

- FOX hunting

full-length cDNA overexpressor gene hunting

- FT-NIR

Fourier transform near-infrared

- GC-TOF/MS

gas chromatography–time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- GO

gene ontology

- HCA

hierarchical cluster analysis

- MS medium

Murashige and Skoog medium

- SA

salicylic acid.

References

- Albinsky D., Kusano M., Higuchi M., Hayashi N., Kobayashi M., Fukushima A., et al. Metabolomic screening applied to Rice FOX Arabidopsis lines leads to the identification of a gene-changing nitrogen metabolism. Mol. Plant. 2010;3:125–142. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J.M., Stepanova A.N., Leisse T.J., Kim C.J., Chen H., Shinn P., et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301:653–657. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. The water–water cycle in chloroplasts: scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;50:601–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker N.R. Chlorophyll fluorescence: a probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008;59:89–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson D.A., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Lipman D.J., Ostell J., Sayers E.W. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D46–D51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch J., Verbsky M.L., Robertson T.L., Larkin J.C., Kunkel B.N. Analysis of resistance gene-mediated defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana plants carrying a mutation in CPR5. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:1196–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar A.S., Thorsteinsdottir H., Martin D.K., Smith A.C., Nast S., Singer P.A. Top ten biotechnologies for improving health in developing countries. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:229–232. doi: 10.1038/ng1002-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmais M., Schmidt J., Le Signor C., Moussy F., Burstin J., Savois V., et al. UTILLdb, a Pisum sativum in silico forward and reverse genetics tool. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P.J., editor. In Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! Vol. 3. Springer, Berlin: 2004. Introduction; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dubouzet J.G., Maeda S., Sugano S., Ohtake M., Hayashi N., Ichikawa T., et al. Screening for resistance against Pseudomonas syringae in rice-FOX Arabidopsis lines identified a putative receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase gene that confers resistance to major bacterial and fungal pathogens in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00568.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant W.E., Dong X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004;42:185–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerinot M.L., Salt D.E. Fortified foods and phytoremediation. Two sides of the same coin. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:164–167. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H., Guiderdoni E., An G., Hsing Y.I., Eun M.Y., Han C.D., et al. Rice mutant resources for gene discovery. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004;54:325–334. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000036368.74758.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges D.M., DeLong J.M., Forney C.F., Prange R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta. 1999;207:604–611. doi: 10.1007/s00425-017-2699-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing Y.I., Chern C.G., Fan M.J., Lu P.C., Chen K.T., Lo S.F., et al. A rice gene activation/knockout mutant resource for high throughput functional genomics. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;63:351–364. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9093-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S., Apweiler R., Attwood T.K., Bairoch A., Bateman A., Binns D., et al. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa T., Nakazawa M., Kawashima M., Iizumi H., Kuroda H., Kondou Y., et al. The FOX hunting system: an alternative gain-of-function gene hunting technique. Plant J. 2006;48:974–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Motohashi R., Kuromori T., Mizukado S., Sakurai T., Kanahara H., et al. A new resource of locally transposed Dissociation elements for screening gene-knockout lines in silico on the Arabidopsis genome. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1695–1699. doi: 10.1104/pp.002774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins G.I. Signal transduction in responses to UV-B radiation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009;60:407–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H.L., Cominelli E., Bailey P., Parr A., Mehrtens F., Jones J., et al. Transcriptional repression by AtMYB4 controls production of UV-protecting sunscreens in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2000;19:6150–6161. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S., Satoh K., Nagata T., Kawagashira N., Doi K., Kishimoto N., et al. Collection, mapping, and annotation of over 28,000 cDNA clones from japonica rice. Science. 2003;301:376–379. doi: 10.1126/science.1081288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.G., Kim S.Y., Kim W.Y., Mackey D., Lee S.Y. Responses of Arabidopsis thaliana to challenge by Pseudomonas syringae. Mol Cell. 2008;25:323–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M., Kamada-Nobusada T., Komatsu H., Takei K., Kuroha T., Mizutani M., et al. Highly sensitive and high-throughput analysis of plant hormones using MS-probe modification and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry: an application for hormone profiling in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1201–1214. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnik T., Szeverenyi I., Bachmann D., Kumar C.S., Jiang S., Ramamoorthy R., et al. Establishing an efficient Ac/Ds tagging system in rice: large-scale analysis of Ds flanking sequences. Plant J. 2004;37:301–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondou Y., Higuchi M., Takahashi S., Sakurai T., Ichikawa T., Kuroda H., et al. Systematic approaches to using the FOX hunting system to identify useful rice genes. Plant J. 2009;57:883–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T., Hirayama T., Kiyosue Y., Takabe H., Mizukado S., Sakurai T., et al. A collection of 11 800 single-copy Ds transposon insertion lines in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2004;37:897–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1365.313x.2004.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T., Takahashi S., Kondou Y., Shinozaki K., Matsui M. Phenome analysis in plant species using loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1215–1231. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T., Wada T., Kamiya A., Yuguchi M., Yokouchi T., Imura Y., et al. A trial of phenome analysis using 4000 Ds-insertional mutants in gene-coding regions of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;47:640–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larmande P., Gay C., Lorieux M., Perin C., Bouniol M., Droc G., et al. Oryza Tag Line, a phenotypic mutant database for the Genoplante rice insertion line library. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D1022–D1027. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lease K.A., Tax F.E., Walker J.C. BRS1, a serine carboxypeptidase, regulates BRI1 signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5916–5921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091065998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Rosso M.G., Strizhov N., Viehoever P., Weisshaar B. GABI-Kat SimpleSearch: a flanking sequence tag (FST) database for the identification of T-DNA insertion mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1441–1442. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R.A. Functional genomics: probing plant gene function and expression with transposons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2021–2026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza C.A., Boccalandro H.E., Giordano C.V., Battista D., Scopel A.L., Ballare C.L. Functional significance and induction by solar radiation of ultraviolet-absorbing sunscreens in field-grown soybean crops. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:117–126. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa M., Ichikawa T., Ishikawa A., Kobayashi H., Tsuhara Y., Kawashima M., et al. Activation tagging, a novel tool to dissect the functions of a gene family. Plant J. 2003;34:741–750. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang S., Zhu W., Hamilton J., Lin H., Campbell M., Childs K., et al. The TIGR Rice Genome Annotation Resource: improvements and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D883–D887. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto A., Lan V.T., Hase Y., Shikazono N., Matsunaga T., Tanaka A. Disruption of the AtREV3 gene causes hypersensitivity to ultraviolet B light and gamma-rays in Arabidopsis: implication of the presence of a translesion synthesis mechanism in plants. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2042–2057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T., Satou M., Akiyama K., Iida K., Seki M., Kuromori T., et al. RARGE: a large-scale database of RIKEN Arabidopsis resources ranging from transcriptome to phenome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D647–D650. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson F., Brunaud V., Duchene S., De Oliveira Y., Caboche M., Lecharny A., et al. FLAGdb++: a database for the functional analysis of the Arabidopsis genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D347–D350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer P.S., McCombie W.R., Sundaresan V., Martienssen R.A. Gene trap tagging of PROLIFERA, an essential MCM2-3-5-like gene in Arabidopsis. Science. 1995;268:877–880. doi: 10.1126/science.7754372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyn W.J., Wand S.J.E., Holcroft D.M., Jacobs G. Anthocyanins in vegetative tissues: a proposed unified function in photoprotection. New Phytol. 2002;155:349–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suesslin C., Frohnmeyer H. An Arabidopsis mutant defective in UV-B light-mediated responses. Plant J. 2003;33:591–601. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M., Kusano M., Takahashi H., Nakamura Y., Hayashi N., Kobayashi M., et al. Rice–Arabidopsis FOX line screening with FT-NIR-based fingerprinting for GC-TOF/MS-based metabolite profiling. Metabolomics. 2010;6:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Swarbreck D., Wilks C., Lamesch P., Berardini T.Z., Garcia-Hernandez M., Foerster H., et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): gene structure and function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D1009–D1014. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S., Sakamoto A., Sato S., Kato T., Tabata S., Tanaka A. Roles of Arabidopsis AtREV1 and AtREV7 in translesion synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:870–881. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatsuji H., Jiang C.J., Sugano S. Salicylic acid signaling pathway in rice and the potential applications of its regulators. JARQ. 2010;44:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Antonio B.A., Kikuchi S., Matsumoto T., Nagamura Y., Numa H., et al. The Rice Annotation Project Database (RAP-DB): 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D1028–D1033. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Enckevort L.J., Droc G., Piffanelli P., Greco R., Gagneur C., Weber C., et al. EU-OSTID: a collection of transposon insertional mutants for functional genomics in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;59:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-8532-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D., Ahn J.H., Blazquez M.A., Borevitz J.O., Christensen S.K., Fankhauser C., et al. Activation tagging in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:1003–1013. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki J., Kojima K., Suzuki K., Kishimoto N., Kikuchi S. The Rice PIPELINE: a unification tool for plant functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D383–D387. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokotani N., Ichikawa T., Kondou Y., Maeda S., Iwabuchi M., Mori M., et al. Overexpression of a rice gene encoding a small C2 domain protein OsSMCP1 increases tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;71:391–402. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9530-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokotani N., Ichikawa T., Kondou Y., Matsui M., Hirochika H., Iwabuchi M., et al. Expression of rice heat stress transcription factor OsHsfA2e enhances tolerance to environmental stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis. Planta. 2008;227:957–967. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizumi T., Tsumoto Y., Takiguchi T., Nagata N., Yamamoto Y.Y., Kawashima M., et al. Increased level of polyploidy1, a conserved repressor of CYCLINA2 transcription, controls endoreduplication in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2452–2468. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Li C., Wu C., Xiong L., Chen G., Zhang Q., et al. RMD: a rice mutant database for functional analysis of the rice genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D745–D748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Tessaro M.J., Lassner M., Li X. Knockout analysis of Arabidopsis transcription factors TGA2, TGA5, and TGA6 reveals their redundant and essential roles in systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2647–2653. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.