Abstract

Elevated plasma levels of homocysteine (Hcy), known as hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy), are associated with osteoporosis. A decrease in bone blood flow is a potential cause of compromised bone mechanical properties. Therefore, we hypothesized that HHcy decreases bone blood flow and biomechanical properties. To test this hypothesis, male Sprague–Dawley rats were treated with Hcy (0.67 g/L) in drinking water for 8 weeks. Age-matched rats served as controls. At the end of the treatment period, the rats were anesthetized. Blood samples were collected from experimental or control rats. Biochemical turnover markers (body weight, Hcy, vitamin B12, and folate) were measured. Systolic blood pressure was measured from the right carotid artery. Tibia blood flow was measured by laser Doppler flow probe. The results indicated that Hcy levels were significantly higher in the Hcy-treated group than in control rats, whereas vitamin B12 levels were lower in the Hcy-treated group compared with control rats. There was no significant difference in folate concentration and blood pressure in Hcy-treated versus control rats. The tibial blood flow index of the control group was significantly higher (0.78 ± 0.09 flow unit) compared with the Hcy-treated group (0.51 ± 0.09). The tibial mass was 1.1 ± 0.1 g in the control group and 0.9 ± 0.1 in the Hcy-treated group. The tibia bone density was unchanged in Hcy-treated rats. These results suggest that Hcy causes a reduction in bone blood flow, which contributes to compromised bone biomechanical properties.

Keywords: homocysteine, tibia, bone density

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a pathological condition whereby the skeleton undergoes remodeling and reduction in bone density (BD).1,2 Osteoporosis is a very prevalent disease that affects more than 75 million people in Europe, the US, and Japan.1 It has a widespread social and economic impact in the global population, costing US$16.9 billion in the US alone.3 Over 10 years, postmenopausal women in the US experienced 5.2 million fractures of the hip, spine, or forearm, which is equivalent to 2 million years with a disability.4 Hence, identifying factors involved in this process, aside from low vitamin D and calcium intake,5 becomes paramount in our investigation.

Homocysteine (Hcy) is a sulfur-containing, nonproteinogenic amino acid formed during the metabolism of methionine.6 Elevated levels of total plasma Hcy are known as hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy). Recently, increased plasma Hcy has been suggested to be an independent risk factor for osteoporosis and bone quality.7,8 In addition, HHcy is accompanied by disruption of biochemical bone turnover markers, osteocalcin, and collagen I C-terminal cross-laps.9 However, the mechanistic role of Hcy in osteoporosis is still unknown.

HHcy-induced oxidative stress may occur as a consequence of either decreased expression or activity of key antioxidant enzymes or increased enzymatic generation of superoxide anions.10 Superoxide anions may react with nitric oxide (NO) to produce peroxynitrite with reduced NO bioavailability,11 which may impair the osteoblast–osteoclast balance, with unpredictable consequences on bone remodeling. An increase in oxidative stress, which leads to reduce NO bioavailability, decreases bone blood flow and hence leads to osteoporosis.12

Blood flow is essential for normal bone growth and bone repair.13 Therefore, inadequate blood flow to skeletal structures could impair normal development and/or the healing process of bone. The two most essential factors in bone healing are stabilization of the osseous fragments and blood flow. After a bone fracture, blood flow to the injury site changes to meet the metabolic needs of the healing tissue.13

Several previous studies have shown that HHcy alters the ability of vasculature to dilate because it decreases NO bioavailability, which increases vascular resistance.14 Considering the convincing studies in which HHcy resulted in increased vascular resistance, we proposed that HHcy rats would have decreased bone blood flow as a consequence of this, thereby altering biomechanical properties such as density and net weight.

Materials and methods

Induction of HHcy

Male Sprague–Dawley rats, 8 weeks of age (250–300 g), were kept in cages at room temperature under a day/night rhythm and fed a standard laboratory chow. The rats were divided into a wild-type group (n = 10) and an HHcy group (n = 12), both groups receiving an identical diet. In accordance with previous studies, to create a condition of mild HHcy, Hcy was supplemented (0.67 g dl-Hcy [Sigma H-4628; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA]/L drinking water) for 8–12 weeks. The low Hcy diet was selected because studies on rats had illustrated that this dose-induced mild HHcy was well tolerated.14 Control rats received Hcy-free water. The animals were killed with sodium pentobarbital (70 mg/kg) at the end of the experiments. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal research and were reviewed and approved by the University of Louisville Animal Care and Use Committee.

Measurement of plasma Hcy

Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast. The samples were stored at −80°C until the day of analysis. Plasma was used to detect the concentrations of Hcy by high-pressure liquid chromatography, vitamin B12, and folate as described previously.9,15

In vivo bone blood flow measurement

Bone blood flow was measured as described previously.13 On the day of the bone blood flow measurement experiment, the rats were anesthetized. Body temperature was maintained between 37°C and 39°C using a heating pad. The left carotid artery was cannulated to measure arterial blood pressure. The left tibia was exposed at a midshaft position by surgical incision, and 5 mM of soft tissue and periosteum were removed to expose the cortex. A laser Doppler flow meter was used to assess bone blood flow. The flow probe was positioned along the anteromedial surface of the tibia. Estimates of flow were obtained every 3–4 sec over a period of 4–6 min. At the conclusion of the experiment, the tibia was excised and weighed.

Measurement of BD

The apparent BD was determined by the Archimedes principle to decide whether there was a change in bone mechanical properties.

Other measures

Height and weight were measured by scale, and tibia mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

Statistical analysis

Values are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean in all four groups. Differences between groups were tested by two-way analysis of variance. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to compare group means, and results were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

There was no significant difference in initial body weights of control (208 ± 0.01) and Hcy-treated (238.1 ± 0.03) rats (Table 1). As expected, plasma Hcy concentrations were significantly increased in the Hcy-treated group (17.2 ± 9 μmol/L) compared with the control group (3.0 ± 5 μmol/L). Serum folate concentration was similar in both groups (35.5 ± 4.2 nmol/L in the HHcy group and 32.5 ± 4.7 nmol/L in the control group), whereas vitamin B12 was significantly lower in the HHcy group (338 ± 49 pmol/L) compared with the control group (450 ± 85 pmol/L). The tibial mass was 1.1 ± 0.1 g in the control group and 0.9 ± 0.1 g in the Hcy- treated group.

Table 1.

Biochemical findings in animals at the end of the treatment period

| Control | Experimental group | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight | 208 ± 0.01 | 238 ± 0.03 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 3.0 ± 5 | 17.20 ± 9* |

| Folic acid, nmol/L | 35.5 ± 4.2 | 32.5 ± 4.7 |

| Vitamin B12, pmol/L | 450 ± 85 | 338 ± 49* |

Note: P < 0.05 versus control.

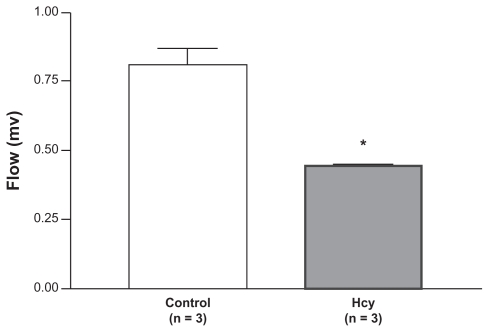

The bone blood flow index was reduced in Hcy-treated rats. Blood flow to the tibia of control rats (0.78 ± 0.09 units, n = 5) was significantly higher than the blood flow to the tibia of Hcy-treated rats (0.51 ± 0.09 units, n = 5) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow index was reduced in Hcy-treated rats. Blood flow to the tibia of control rats (0.78 ± 0.09 units) was significantly higher than blood flow to the Hcy-treated rats (0.51 ± 0.09 units).

Note: *P < 0.05 compared with control.

Abbreviation: Hcy, homocysteine.

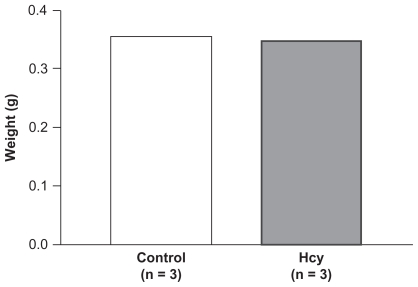

There was no difference in right tibia wet weight in Hcy-treated rats (0.3 g, n = 3). There was no difference in the wet tibia weight for control and Hcy-treated rats (n = 5) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

No difference was observed in right tibia wet weight in Hcy-treated rats. There was no difference in the tibia wet weight between control and Hcy-treated rats.

Abbreviation: Hcy, homocysteine.

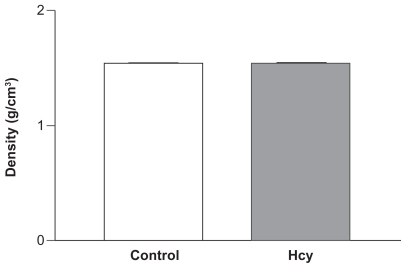

The tibia BD was unchanged in Hcy-treated rats. The densities of the tibias from control and Hcy-treated rats suggested no difference (1.6 g/cm3, n = 5) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Density was unchanged in Hcy-treated rats. The density of the tibias between control and Hcy-treated rats suggested no difference.

Abbreviation: Hcy, homocysteine.

Discussion

The present study clearly demonstrated that there was a significant decrease in bone blood flow in Hcy-treated rat tibia versus control rat tibia (Figure 1). This result was consistent with our plethora of evidence that indicated Hcy had some role in modulating those systems involved in vasodilation both in vivo and in vitro. A study in humans showed that high plasma Hcy level was independently associated with greater brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity.16

Kumar et al showed decreased carotid artery blood flow in heterozygote cystathionine β-synthase mice (CBS+/−, genetically HHcy mice).17 Elevated plasma levels of Hcy in these mice (CBS+/−) caused an increase in arterial remodeling, in part due to an increase in the collagen/elastin ratio, resulting in amplified vascular resistance, and led to a measured decrease in carotid artery blood flow.17 One possible mechanism for this was that Hcy caused oxidative stress that led to the activation of matrix metalloproteinase in the extracellular matrix.

In concordance with those studies, another study showed that HHcy impaired angiogenesis in a murine model of limb ischemia. This could have resulted in greater vascular resistance and decreased bone blood flow.18 Riza Erbay et al showed that patients with slow coronary flow had high level of plasma Hcy compared with patients with normal coronary flow; this study suggested a correlation between high Hcy and coronary flow and a possible role in the pathogenesis of impaired flow.19

Hence, we clearly see a role of Hcy in modulating bone blood flow in a variety of contexts and experimental models. Our results have provided yet another context and model by which Hcy alters bone blood flow. The pathological consequences of this remain to be elucidated.

We proposed that there would be a decrease in BD in the Hcy-treated group of rats. However, we did not note any changes in density or dry or wet weight of tibia among the Hcy group versus control rats (Figures 2 and 3). However, BD is not the only clinically important value in determining susceptibility to fracture; in fact, many studies have noted bone quality as a major risk factor for fracture, with differences in the following measures: geometry, bone mass distribution, trabecular bone architecture, microdamage, remodeling activity, bone mineral, and matrix tissue properties.20–22 Therefore, although BD did not decrease under our experimental conditions, there could possibly have been a change in bone quality. However, we did not perform these measures, and this is warranted for future study.

Both folate and vitamin B12 are cofactors of the methionine synthase reaction and play an important role in Hcy metabolism.6 The consumption of folate and vitamin B12 is high in the presence of high Hcy concentrations in plasma. In the present study, serum vitamin B12 concentration was significantly lower in the Hcy-treated group compared with control rats; however, there was no significant change in folate concentration. As vitamin B12 and folate are directly involved in the regulation of Hcy concentrations in blood, the question arises whether a reduction in concentrations of these vitamins has any effect on biochemical markers of bone. Carmel et al demonstrated reductions in biochemical markers (osteocalcin) in vitamin B12-deficient individuals.23

Mice treated with folate antagonist showed reduced bone growth,24 and this was further supported by data suggesting that folate may have significant effects on bone that are independent of Hcy.25 In contrast, recently, other studies have shown that folate supplementation does not affect biochemical markers of bone turnover, although it decreases Hcy concentrations in healthy subjects.26

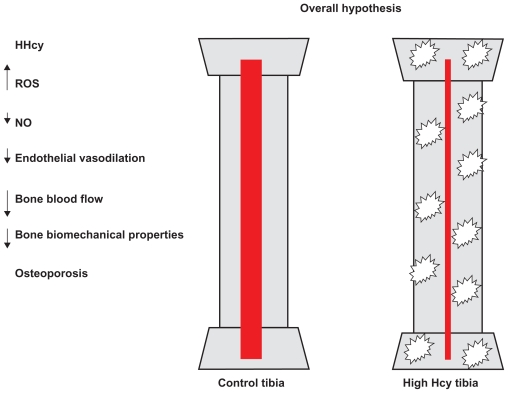

We found no difference in weight and density, so there may be some compensatory mechanism. Further studies are required. A longer exposure to Hcy or a higher plasma level could further reduce bone blood flow and potentially compromise bone mechanical properties, as suggested in human studies. Previous evidence from our laboratory suggested that Hcy increased oxidative stress and decreased the bioavailability of NO, an important dilator of the bone vasculature, and hence supports the hypothesis presented in Figure 4. In summary, the present study provides strong evidence that HHcy is a major cause of weakening of the bone. Future studies are required to clarify the mechanisms of the HHcy effect.

Figure 4.

The hypothesis was that high levels of Hcy lead to increased ROS, decreased NO bioavailability and other factors, decreased endothelial vasodilation, and decreased bone blood flow, which could lead to decreased biomechanical properties. The hypothesis was that high levels of Hcy lead to increased vascular resistance from decreased vasodilation, which could lead to decreased biomechanical properties, including decreased BD.

Abbreviations: HHcy, hyperhomocysteinemia; Hcy, homocysteine; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Kathleen Hamilton for taking bone density measurements. A part of this study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL-71010 and NS-51568.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Who are candidates for prevention and treatment for osteoporosis? Osteoporos Int. 1997;7(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01623453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lippuner K, Golder M, Greiner R. Epidemiology and direct medical costs of osteoporotic fractures in men and women in Switzerland. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(Suppl 2):S8–S17. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummings SR, Melton LJ. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chrischilles E, Shireman T, Wallace R. Costs and health effects of osteoporotic fractures. Bone. 1994;15(4):377–386. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90813-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, et al. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in the elderly women. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(23):1637–1642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selhub J. Homocysteine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean RR, Jacques PF, Selhub J, et al. Homocysteine as a predictive factor for hip fracture in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(20):2042–2049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Meurs JB, Dhonukshe-Rutten RA, Pluijm SM, et al. Homocysteine levels and the risk of osteoporotic fracture. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(20):2033–2041. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozdem S, Samanci S, Tasatargil A, et al. Experimental hyperhomocysteinemia disturbs bone metabolism in rats. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2007;67(7):748–756. doi: 10.1080/00365510701342088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lentz SR, Erger RA, Dayal S, et al. Folate dependence of hyperhomocysteinemia and vascular dysfunction in cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(3):H970–975. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banfi G, Iorio EL, Corsi MM. Oxidative stress, free radicals and bone remodeling. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46(11):1550–1555. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez-Rodriguez MA, Ruiz-Ramos M, Correa-Munoz E, Mendoza-Nunez VM. Oxidative stress as a risk factor for osteoporosis in elderly Mexicans as characterized by antioxidant enzymes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming JT, Barati MT, Beck DJ, et al. Bone blood flow and vascular reactivity. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169(3):279–284. doi: 10.1159/000047892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steed MM, Tyagi N, Sen U, Schuschke DA, Joshua IG, Tyagi SC. Functional consequences of the collagen/elastin switch in vascular remodeling in hyperhomocysteinemic wild-type, eNOS−/−, and iNOS−/− mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299(3):L301–311. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00065.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sen U, Tyagi N, Kumar M, Moshal KS, Rodriguez WE, Tyagi SC. Cystathionine-beta-synthase gene transfer and 3-deazaadenosine ameliorate inflammatory response in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293(6):C1779–1787. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00207.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tayama J, Munakata M, Yoshinaga K, Toyota T. Higher plasma homocysteine concentration is associated with more advanced systemic arterial stiffness and greater blood pressure response to stress in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2006;29(6):403–409. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar M, Tyagi N, Moshal KS, et al. Homocysteine decreases blood flow to the brain due to vascular resistance in carotid artery. Neurochem Int. 2008;53:6–8. 214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosch-Marce M, Pola R, Wecker AB, et al. Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia impairs angiogenesis in a murine model of limb ischemia. Vasc Med. 2005;10(1):15–22. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm585oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riza Erbay A, Turhan H, Yasar AS, et al. Elevated level of plasma homocysteine in patients with slow coronary flow. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102(3):419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manolagas SC. Corticosteroids and fractures: a close encounter of the third cell kind. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(6):1001–1005. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fratzl P, Gupta HS, Paschalis EP, Roschger P. Structure and mechanical quality of the collagen–mineral nano-composite in bone. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:2115–2123. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCreadie BR, Goldstein SA. Biomechanics of fracture: is bone mineral density sufficient to assess risk? J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(12):2305–2308. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.12.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmel R, Lau KH, Baylink DJ, Saxena S, Singer FR. Cobalamin and osteoblast-specific proteins. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(2):70–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807143190202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iqbal MP, Ahmed M, Umer M, Mehboobali N, Qureshi AA. Effect of methotrexate and folinic acid on skeletal growth in mice. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(12):1438–1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McFarlane SI, Muniyappa R, Shin JJ, Bahtiyar G, Sowers JR. Osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease: brittle bones and boned arteries, is there a link? Endocrine. 2004;23(1):1–10. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:23:1:01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann M, Stanger O, Paulweber B, Hufnagl C, Herrmann W. Folate supplementation does not affect biochemical markers of bone turnover. Clin Lab. 2006;52:3–4. 131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]