Abstract

Increased gap junction expression in lamina propria myofibroblasts and urothelial cells may be involved in detrusor overactivity, leading to incontinence. Immunohistochemistry was used to compare connexin (Cx) 26, 43, and 45 expression in the bladders of neonatal, adult, and spinal cord-transected rats, while optical imaging was used to map the spread of spontaneous activity and the effects of gap junction blockade. Female adult Sprague-Dawley rats were deeply anesthetized, a laminectomy was performed, and the spinal cord was transected (T8/T9). After 14 days, their bladders and those of age-matched adults (4 mo old) and neonates (7-21 day old) were excised and studied immunohistochemically using frozen sections or optically using whole bladders stained with voltage- and Ca2+-sensitive dyes. The expression of Cx26 was localized to the urothelium, Cx43 to the lamina propria myofibro-blasts, and Cx45 to the detrusor smooth muscle. While the expression of Cx45 was comparable in all bladders, the expression of Cx43 and Cx26 was increased in neonate and transected animals. In the bladders of adults, spontaneous activity was initiated at multiple sites, resulting in a lack of coordination. Alternatively, in neonate and transected animals spontaneous activity was initiated at a focal site near the dome and spread in a coordinated fashion throughout the bladder. Gap junction blockade (18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, 1 μM) abolished this coordinated activity but had no effect on the uncoordinated activity in adult bladders. These data suggest that coordinated spontaneous activity requires gap junction upregulation in urothelial cells and lamina propria myofibroblasts.

Keywords: lamina propria myofibroblasts, optical mapping, urothelium, voltage-and Ca2+-sensitive dyes

Injury to the Spinal Cord is associated with bladder overactivity, characterized by large uncontrollable contractions that may not be coordinated to relaxation of the bladder outflow. Various treatments have been proposed, including stimulation of the sacral spinal cord (2), treatment with anticholinergic agents (6), or instillation into the bladder of vanilloid agents or botulinum toxin (12, 21). These treatments are directed toward suppressing spinal reflexes that appear to become more obvious after the removal of descending inhibition, or blockade of the action of motor neurotransmitters to the smooth muscle of the bladder (detrusor). This range of therapies reflects the fact that no single option has emerged as an unrivaled success.

The spontaneous activity that accompanies spinal cord damage is similar to that exhibited by neonatal animals. This has been studied extensively in rats where large-amplitude contractions are recorded in isolated neonatal bladders (14), as well as in strips isolated from these bladders (18). The contractions in isolated preparations were resistant to neurotoxins such as tetrodotoxin (TTX). However, when spinal cord connections to the bladder were maintained, TTX enhanced the activity (14, 15). This suggests that spontaneous activity might have an origin within the bladder (11) but that the spinal cord exerts an inhibitory control.

The origin of such spontaneous activity, and the mechanism that facilitates its coordination in the bladder wall, especially in the bladders of neonatal and spinal cord-injured animals, is not known but may be coordinated by nonneuronal structures (5). It may lie within the smooth muscle cells themselves, require facilitation by interstitial cells that have been described in the detrusor layer (4), or in the suburothelial space (17), or by the production of activators from the urothelium (7) that could increase local reflex activity. A characteristic of all these cells is that they are coupled by gap junctions that can coordinate intrinsic activity generated in a small group of cells.

We have demonstrated recently (9) that it is possible to map, in real time, changes in intracellular Ca2+ and membrane potential in the whole bladder, using dual photodiode arrays to measure simultaneously these variables conducting across the bladder surface. We hypothesized that in bladders from neonatal and spinal cord-injured rats, in contrast to normal adult rats, the generation of large, spontaneous pressure transients is associated with coordinated changes in intracellular Ca2+ and membrane potential, Em, across significant regions of the bladder wall. Furthermore, we hypothesize the coordinated activity is facilitated by enhanced gap junction transmission. We tested this hypothesis by examining the effects of gap junction blockers on intravesical pressure and Ca2+/Em waves and also by measuring the relative amount of gap junction proteins in bladders from the different groups by immunohistochemistry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental preparations

Isolated bladders were used from three groups of rats: neonatal animals (3–21 day old); normal adult rats (4 mo old); and a group of the adult rats that underwent spinal (T8/T9) cord transection as described previously (10). Briefly, animals in the latter group were anesthetized with an isoflurane/O2 mixture (2%: 98%), and after a laminectomy the dura and spinal cord were cut. Gelfoam (Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI) was packed between the cut ends, the muscle and skin were sutured, and the animals were allowed to recover with prophylactic antibiotics (ampicillin, 100 mg/day im). For the first 1–2 wk following the operation, their bladders were emptied two to three times per day by manual abdominal compression until the animals developed their own micturition reflexes. Animals were used about 4 wk after the operation. All procedures conformed to institutional guidelines and were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Neonates were killed by decapitation, and the bladders were immediately removed. Adult rats were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane in oxygen, the bladder was removed following a laparotomy, and the animal was killed by inhaling CO2. Bladders were placed immediately in physiological saline (PS; see below).

Experimental procedure

The bladder was cannulated with a 22-gauge needle per urethra, used initially to load the tissue with fluorochromes. This was achieved by filling the lumen first with the Ca2+ indicator Rhod-2 AM (20 μM; Molecular Probes) dissolved in 14:1 (PS:DMSO) for 30 min at 37°C, and then after its aspiration with the membrane potential probe Di-4-ANEPPS (10 μM, Molecular Probes) dissolved in 19:1 (PS:DMSO) with the same protocol. The bladder was emptied, filled with PS, and placed in the experimental chamber (empty volume ~2.4 ml) machined from heat-conducting epoxy resin. The chamber was placed on a Peltier block (CSMI, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) to maintain the temperature at 37 ± 0.5°C, and superfused with PS at a rate of 1 ml/min.

Recording systems

Intraluminal bladder pressure was measured via a urethral cannula by attaching it, in line with a three-way tap, to a pressure transducer, with reference to atmospheric pressure. The three-way tap also allowed the bladder to be filled to different volumes.

Intracellular Ca2+ and Em were recorded from the surface of the bladder as fluorescence images focussed onto two 16 × 16-element photodiode arrays with 10-M feedback resistors (C675-103, Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). Each diode had a sensing area of 0.95 × 0.95 mm and an interpixel spacing of 1.1 mm. The photodiode array output was amplified (LBC-2 Argo Transdata, Clinton, CT), digitized as 12 bits (DAP 3400/a, Microstar Laboratories, Bellevue, WA), and stored in computer memory. A typical file was sampled at 2 kHz for 30–60 s, consisting of 256 Ca2+, 256 Em, and 16 instrumentation channels; the sampling arrangement ensured that the delay between recording a Ca2+ or Em signal from the same site was 3.9 μs. The alignment of separate images was facilitated with a 16 × 16 graticule (Graticules, Tonbridge, UK) in the illumination light path to generate a reference array over the bladder.

The bladder was illuminated by collimated light from a 100-W tungsten-halogen lamp, directed through a band-pass filter (520 ± 20 nm) to a 575-nm long-wave-pass dichroic mirror (Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT) and an 85-mm, f1:1.4 lens (Nikon). Fluorescence was collected by the same lens and, after passage through the 575-nm dichroic mirror, was split with a 635-nm long-wave-pass dichroic mirror; low-wavelength light represented the Rhod-2, Ca2+ signal, and higher-wavelength light the di-ANEPPS, Em signal. Further details have been described elsewhere (3, 9).

Solutions

Preparations were bathed in a physiological solution containing (in mM) 118 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2[H18528] 6H2O, 1.8 CaCl2, and 14 glucose, gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH 7.4. 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid (18β-GA) was added to the physiological solution as aliquots from a 1 mM aqueous stock solution. All chemicals were from Sigma or Fischer.

Connexin immunofluorescence

Bladders from different animals than those used for physiological measurements were utilized. The bladders were cut open and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by 30% sucrose, before being rapidly frozen in isopentane/dry ice (−70°C for 2 min). Frozen tissue sections (10 μm) were thaw-mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated slides. Sections were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies to connexins (Cx) 26 (monoclonal mouse IgG Zymed Laboratories), 43 (monoclonal mouse IgG, Chemicon International) and 45 (monoclonal mouse IgG, Chemicon International) made up to 1, 1, or 2 μg/ml, respectively, in PBS, with 5% BSA/0.15% glycine. Negative controls were performed on bladder sections by omitting the primary antibody.

The primary antibody was removed by washing in PBS/5% BSA. Sections were then incubated for 1 h atroom temperature in Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L; 4 μg/ml, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) diluted in PBS with 5% BSA and 0.15% glycine. Cell nuclei were subsequently stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:40,000 dilution, Molecular Probes), which forms fluorescent complexes with natural double-stranded DNA. Rhodamine-phalloidin (1:250 dilution, Molecular Probes) was used as a fluorescent marker for F-actin. Immunolabeled sections were examined by confocal laser-scanning microscopy using an instrument equipped with argon, krypton, and helium-neon lasers (TCS-NT, Leica). A series of images was sequentially recorded for each channel to avoid signal crossover. Slides were mounted with Citifluor (UKC Chem Labs, Kent, UK) and examined with fluorescence microscopy. Positive controls for the primary antibodies were performed in adult rat heart, brain, and dorsal root ganglia tissue sections.

The amount of Cx labeling was examined in a semiquantitative way by analyzing sections from different bladders using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov). The sections were rendered into black-and-white bitmaps after they were color-filtered to render images for the Cx, nuclear, or smooth muscle labels alone. Areas for analysis corresponded to the urothelial, suburothelial, or muscle layers in the sections. The percent area occupied by the label was expressed as a ratio of the number of nuclei to normalize for any variation in cellular component in different sections.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are shown as mean ± SD, or in the case of immunohistochemical data, as median (25%, 75% interquartiles). Differences between normal data sets were tested with Student's t-test, and between skewed data sets with a Mann-Whitney U-test; the null hypothesis was rejected when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Spontaneous pressure transients and effects of a gap junction blocker

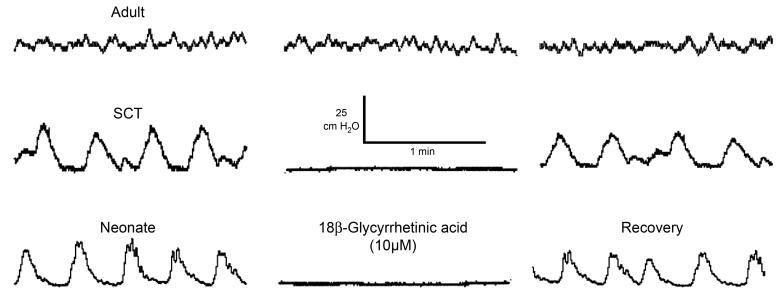

Figure 1 shows examples of intravesical pressure recordings from isolated rat bladders taken from normal adults, adult rats with spinal cord-transected (SCT), and neonatal rats. In normal adult bladders, low-amplitude transients with no consistent pattern were recorded (amplitude 3.4 ± 1.6 cmH2O, frequency 12 ± 4 min−1). In contrast, in bladders from SCT rats or from neonatal animals regular, large-amplitude transients, but of lower frequency, were recorded (SCT, 28.4 ± 8.1 cmH2O, 3.5 ± 1.0 min−1; neonatal, 27.2 ± 7.6 cmH2O, frequency 3.0 ± 1.0 min−1). In the SCT and neonatal bladders, the amplitudes of the transients were enhanced by increasing the volume filling the bladder.

Fig. 1.

Effect of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid on intravesical bladder pressure. Intravesical pressure recordings from normal adult (A), spinal cord-injured adult (SCI; B) and normal neonatal (C) rat bladders. At the first break, 10 μM 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid was added to the bath fluid and recordings were made ~15 min later. The agent was washed out at the second break, and a similar interval was left before recording was resumed.

The middle panels of Fig. 1 show the effect of the gap junction blocker 18β-GA (10 μM) added to the superfusate. With adult bladders from normal animals, the small, spontaneous transients were unaffected by the agent and by its washout. In contrast, with bladders from SCT adult and neonatal rats the spontaneous contractions were abolished completely, and similar results were observed in eight SCT and neonatal bladders. Activity in these latter groups was restored completely on washout of the 18β-GA.

Simultaneous intracellular Ca2+ concentration and Em transients in whole bladders

Intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and Em transients were measured as a 16 × 16 array on the ventral surface of rat bladders from the three groups. Figure 2 shows examples of [Ca2+]i (A) and Em (B) arrays from a normal adult bladder recorded over 60 s. The time from the beginning of each frame to the initiation of each transient was measured, and the shortest delay was taken as a reference point. From this point, isochronal maps were constructed connecting regions of similar delays and these are shown below the arrays: the darker the color, the greater the delay. The maps show a disorganized pattern of multiple, small foci that have no obvious pattern. Figure 2, C and D, shows equivalent [Ca2+]i and Em isochronal maps from a SCT adult rat. In contrast to the maps from the normal adult bladder, there were at most two focal points that covered the surface. The conduction velocity (CV) of wavefront spread in the SCT maps was measured over a distance of 1 mm from the focal point: greater distances were not used as they might have been confused by wavefronts from the other foci, if present. For the [Ca2+]i measurements, the CV was 6.2 ± 0.8 mm/s (n = 6), and for Em the CV was 48.3 ± 5.1 mm/s (n = 6). Similar measurements were also made in neonatal bladders, with results similar to those seen in SCT adult bladders, with single or at most double foci for the origin of [Ca2+]i and Em waves, with corresponding CVs of 4.7 ± 0.7 (n = 8) and 46.4 ± 5.4 mm/s (n = 8). When possible CV was measured from a focal point in the maps from normal adult bladders. Values for the [Ca2+]i and Em maps were 2.2 ± 0.9 (n = 7) and 28.6 ± 3.7 mm/s (n = 7), respectively, and were significantly smaller than values from the SCT and neonatal groups.

Fig. 2.

Intracellular [Ca2+] and membrane potential, Em, recordings from the ventral surface of rat bladders. A:16 × 16 array of Ca2+ transients from a normal adult bladder. Bottom: isochronal map from the transient array. Isochronal intervals, 92 ms. B: corresponding Em transients from the same recording, with the derived isochronal map below. Isochronal intervals, 8 ms. C: isochronal map of Ca2+ transients from a SCI adult bladder. Isochronal intervals, 42 ms. D: corresponding Em transients from the same recording, with the derived isochronal map. Isochronal intervals, 4 ms.

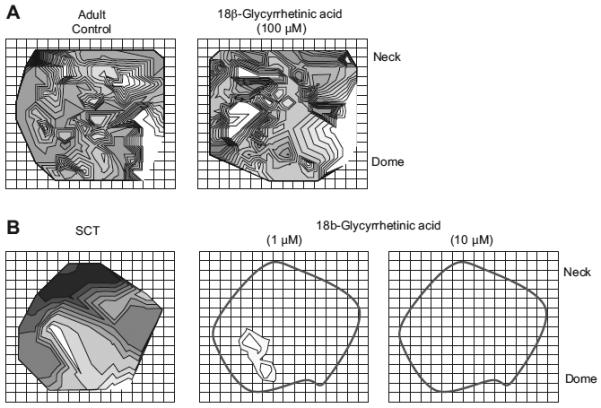

Effect of 18β-GA on [Ca2+]i and Em conduction maps

As 18β-GA suppressed selectively the pressure transients in neonatal and SCT bladders, its effect on the isochronal conduction maps was also investigated. Figure 3A shows Ca2+-isochronal maps in an adult bladder before and after exposure to 100 μM 18β-GA. No discernible effects of the agent were observed; the disorganized map of isochronal lines remained: corresponding small and irregular pressures traces were also retained, as in Fig. 1. By contrast, with bladders from spinal cord-injured adult rats 1 μM 18β-GA almost completely suppressed the Ca2+ transients and Em transients (not shown), and the corresponding isochronal map shows only a localized spread from the same initial focus. The black contoured line traces the outline of the bladder as seen before administration of the gap junction blocker. 18β-GA (10 μM) completely abolished the transients, permitting no map to be drawn. Similar results were obtained with n = 6 SCT bladders and also n = 8 neonatal bladders with 10 μM 18β-GA.

Fig. 3.

Effect of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid on Ca2+ transient isochronal maps. A: control isochronal map of a normal adult bladder and a comparison isochronal map of the effect of 100 μM 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid. In normal adult bladders, there was a disorganized spread of activity that was not affected by 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid. B: control isochronal map of a spinal cord-transected rat bladder and the effect of 1 μM and 10 mM 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid on the same bladder. The activity originated from a single focus that spread across the bladder surface. In the presence of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, activity was severely curtailed at 1 mM, and abolished completely at 10 μM, as seen by an absence of isochrones. The outline demarcates the visible boundary of the bladder.

Cx distribution in bladders from SCT and neonatal rats

Because of the significant effect of 18β-GA on both the pressure transients and the [Ca2+]i and Em conduction maps in SCT and neonatal bladders, the expression of different Cx subtypes throughout the bladder wall in the three experimental groups was measured. We have demonstrated in a previous paper (9) the important role of the urothelial/suburothelial layers in generating spontaneous activity in response to perturbations such as bladder stretch. We hypothesized that Cx abundance particularly associated with these layers might be different in SCT and neonatal animals compared with those from normal adult bladders. We therefore measured Cx43, associated with interstitial cells in the suburothelial space, but also between smooth muscle bundles; Cx45, associated with detrusor smooth muscle; and Cx26, associated with the urothelium. The relative area of Cx labeling (green in Figs.4–6,) was measured in relation to the number of nuclei (blue) in the same field to record any relative changes in Cx in the various layers of the bladder wall relative to cell number.

Fig. 4.

Connexin 43 (Cx43) labeling in the urothelial/suburothelial layer of the bladder wall: green, Cx43; blue, nuclei; red, smooth muscle. A: labeling in the normal adult bladder; the urothelium (uro), and suburothelium (suburo) layer are demarcated. An invagination of the lumen with no nuclear stain can be seen in the top of the section. The white box indicates an area used for analysis. See text for details. B: labeling in the SCI adult bladder. C: plot of normalized Cx43 labeling in sections from normal and SCI adult rats. Median data (25%, 75% interquartiles). *P < 0.05 vs. normal adult bladder. D: labeling in the normal neonatal bladder. Magnification ×400 for all sections.

Fig. 6.

Cx26 labeling in the bladder wall: green, Cx26; blue, nuclei; red, smooth muscle. A: normal adult bladder. B: neonatal bladder. C: SCI adult bladder. D: normalized Cx26 labeling in samples from the 3 bladder groups. Median data (25%, 75% interquar-tiles). *P < 0.05 vs. normal adult bladder. Magnification ×400 for all sections.

Figure 4 shows data for Cx43: in the suburothelial space from an adult bladder section (A) and a similar section from an SCT rat (B), where the labeling appeared more dense. Cx43 labeling shows green, with cell nuclei showing blue. There was abundant Cx43 labeling in the suburothelial layer but very little labeling in the urothelium itself. The data were quantified by an examination of an area demarcated, for example the white box in Fig. 4A, by the recording of the percent area of Cx43 labeling normalized to the number of DAPI-labeled nuclei to account for any variation in cell density. Figure 4C shows that the normalized Cx43 density was significantly greater in samples from SCT rats. In the neonatal bladder, Cx43 labeling was more discretely localized at the interface between the urothelium and suburothelium (Fig. 4D) and was more difficult to quantify as with the adult bladder sections. The red labeling in this section indicates smooth muscle and shows that the suburothelial layer thickness was much smaller in the neonatal bladder.

Cx43 labeling was also observed between muscle bundles in the detrusor layer, especially in samples from SCT rats. Figure 5A shows an example from an SCT rat where prominent Cx43 labeling between cell bundles was observed; such labeling was not generally observed in tissue from normal adult rats. Figure 5B shows Cx45 labeling as small discrete points overlaying the muscle cells. Cx45 labeling was confined to the detrusor muscle and is observed as small particles (green) overlaying the smooth muscle (red). The density of Cx45 labeling (percent area per DAPI-labeling particle) was not different in any of the three groups (adult normal, 0.0096 [0.0038, 0.0340]; adult SCT, 0.0273 [0.0187, 0.0312]; neonatal, 0.01771 [0.0095, 0.0238]).

Fig. 5.

Cx labeling in the detrusor layer of the bladder wall: green, Cx; blue, nuclei; red, smooth muscle. A: Cx43 labeling in a section from a SCI animal. B: Cx45 labeling in a section from a normal adult rat bladder. Magnification ×400 for all sections.

Figure 6 shows data for Cx26 labeling for samples from normal adult (A), SCT adult (B), and neonatal (C) bladders. In this case labeling was most intense in the urothelial layer and relatively negligible in the suburothelial and detrusor layers. Labeling was more intense in the SCT compared with normal adult bladders. In the neonatal bladders the urothelial layer was thinner, but in this layer Cx26 density was also greater. Figure 6D shows the relative labeling in the three groups; both the SCT and neonatal bladders had similar densities and were greater than the normal adult bladder. However, it should be noted that in some of the latter groups the labeling was particularly strong, as evidenced by the large 75% interquartile values in Fig. 6D and exemplified in Fig. 6C.

DISCUSSION

Large-amplitude, organized, spontaneous contractions were recorded from the bladders of neonatal and SCT adult rats. In contrast, lower-amplitude, more disorganized activity was found in normal adults. The contractile frequencies seen in our neonatal and SCT rats were similar to those reported for neonates in a previous study (14), where frequencies increased between 3 and 21 days (the upper age range of the neonatal animals used in our studies). We made no systematic study of the age dependence of activity or any associated functional or structural changes due to the relative small numbers of animals used.

The gap junction blocker 18β-GA caused profound and reversible changes to the spontaneous activity of rat bladders from neonatal animals and adult animals with SCT. In contrast, the apparent random pattern of spontaneous activity in normal adult bladders was unaffected. The altered pattern of spontaneous activity in the neonate and SCT bladders was mirrored by a larger immunofluorescent signal from Cx26 and Cx43. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that spontaneous activity in these bladders is dependent on coupling through certain gap junctions.

18β-GA has previously been shown to reduce electrotonic coupling, as well as disrupt the intercellular movement of markers such as neurobiotin between detrusor and other smooth muscle myocytes, using small bundles of isolated tissues, through an action that was ascribed mainly to be on gap junctions (8, 22). However, 18β-GA did not show any significant effect on the irregular pressure transients or the isochronal Ca2+ and Em maps recorded from whole adults bladders in this study. The lack of effect on pressure transients may be due to the lower concentration used in this study (10 vs. 40 μM); however, even concentrations as high as 100 μM had no action on the irregular and chaotic intracellular Ca2+ and Em isochronal maps and suggested that such activity is not due to coupled spontaneous activity. In contrast, 1 and 10 μM 18β-GA was effective in bladders from neonatal and SCT adult rats, suggesting that gap junction coupling was important to generate the large pressure transients. In neonates and SCT rats, the spontaneous activity appeared to be coordinated, with spontaneous activity originating from pacemaker regions around the bladder dome. This organization of spontaneous activity may be a compensatory mechanism to allow for bladder emptying in the absence of an operational nervous system.

The smooth muscle in the detrusor layer is composed of separate muscle bundles that do not appear to have significant intercommunication. This separateness is also suggested during denervation, when some muscle bundles are severely affected, while others remain largely unchanged (5). However, spontaneous pressure changes in the bladder lumen would require the coordinated activity of a significant part of the bladder wall, which does suggest some degree of communication between muscle bundles. This role may be assumed by interstitial cells that surround muscle bundles and may functionally connect them to their neighbors. One characteristic of interstitial cells is that they are functionally connected via gap junctions composed of Cx43 (20) in contrast to coupling of detrusor smooth muscle cells themselves, which is mainly through Cx45 (16). The Cx immunolabeling in this study showed that Cx45 was not different in samples from the three groups of rats. However, the Cx43 label in the detrusor layer was more intense in those from neonatal and SCT rats. This is in agreement with the observation that c-kit labeling of cells between muscle bundles was greater in human detrusor samples obtained from patients with neuropathic detrusor overactivity compared with those from functionally normal bladders (1). C-kit has been used to identify interstitial cells, and taken together these results suggest that increased spontaneous activity in the bladder of patients and animals with spinal cord lesions may be facilitated by increased communication of adjacent muscle bundles via interstitial cells, coupled through gap junctions composed of Cx43.

Our data suggest that spontaneous detrusor contractions are maintained by Ca2+ action potentials, which depolarize the membrane and activate voltage-gated L- or T-type Ca2+ channels to elevate intracellular Ca2+. This is evidenced by the following findings. 1) An overlay of voltage and Ca2+ traces from equivalent regions at the initiation site in Fig. 2, C (Ca2+) and D (voltage), showed that membrane depolarization preceded the rise in intracellular Ca2+ by tens of milliseconds (not shown). 2) The spread of membrane potential was faster than the propagation of intracellular Ca2+ signals. If intracellular Ca2+ transients were responsible for membrane depolarization, the CV for Ca2+ and voltage would be more similar. 3) The Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine (10 μM) abolishes spontaneous detrusor contractions.

The diffusion of intracellular Ca2+ between cells connected by gap junctions may account for the slower Ca2+ propagation, particularly between detrusor myocytes. The reason that intra-cellular Ca2+ propagation is faster in pathological bladders compared with controls, given that Cx45 levels in the detrusor remain unchanged, may be due to faster propagation between cells in the urothelium and lamina propria, where Cx26 and Cx43 expression is increased, respectively, and more effective coupling between detrusor bundles. We have evidence that the stretch-induced release of ATP from the urothelium increases lamina propria myofibroblast pacemaker activity. We hypothesize that these pacemaker cells, in turn, modulate detrusor spontaneous activity by releasing a yet to be identified factor. This factor may act directly on the detrusor smooth muscle cells, or indirectly through the stimulation of nerves that lie within the lamina propria region. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that during filling, the urothelium, lamina propria myofibroblasts, and the detrusor come within close proximity to one another. The optical imaging of sheets used in this study showed the sum of the activity from the various layers of the bladder. The involvement of the individual layers will be addressed in future studies by examining the optical activity of bladder wall cross sections, as has been previously studied (9).

The most striking changes to Cx distribution were in the urothelium, where Cx26 was strongly labeled. In the neonatal bladders, and in particular those from SCT adult rats compared with normal adult bladders, there was a large increase in Cx26 label. This Cx subtype has been found in a number of epithelial membranes, where it forms large conductance channels. The increase in Cx26 expression has important implications for urothelial function, as the urothelium is regarded as a sensory element in bladder signaling, releasing ATP when it is stretched, as would occur for example during bladder filling. Cx hemichannels, including those formed of Cx26, allow the release of intracellular agents such as ATP into the extracellular space (19), and an increase in their number would obviously increase this release. Alternatively, it has been suggested by some (23) that gap junctions between contiguous cells formed of Cx26 may have a preference for anions over cations (although others say the opposite, that Cx26 prefers cations and Cx32 anions) (13). Many biologically active molecules such as ATP and cyclic nucleotides will be negatively charged at physiological pH. An increase in intercellular communication between urothelial cells could harmonize intracellular ATP levels and generate a more homogeneous release over a larger area of tissue. Whatever the mechanism, the implication is that the urothelium may play a role in the initiation and maintenance of spontaneous pressure transients in the bladder through Cx26. Whether this is linked to the increase in activity in the detrusor through the generation of spontaneous waves of [Ca2+]i and Em changes remains to be ascertained.

In summary, neonatal and SCT rat bladders display organized patterns of voltage and Ca2+ transients whereas normal adult bladders show uncoordinated activity. The differences in activity appear to correlate with the increased magnitudes of spontaneous pressure transients in neonates and SCT compared with adults. Expression of Cx26 and Cx43 was increased in neonatal and SCT bladders. Accordingly, spontaneous bladder activity was abolished with gap junction blockade in these animals but had no effect in normal adult bladders. Gap junctions appear to have a major role in mediating intrinsic contractile activity in the bladder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank William Hughes and Travis Wheeler of the departmental machine shop and Gregory Szekeres of the departmental electronic shop for construction of optical components and recording chambers.

GRANTS

This work is funded by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-064280 to A. Kanai. C. Fry is grateful to the British Journal of Urology International for a travel grant to Pittsburgh, PA.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

The photomicrographs in Figs. 4A,6A, and 6C of this Article in Press contain digital artifacts that obscure portions of the images obtained. This problem has been corrected in the final published version of the manuscript. The authors apologize for the previous error, which arose from the methods used for image analysis and was not noticed in the final submission. The problems identified did not alter the conclusions reached in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biers SM, Reynard JM, Doore T, Brading AF. The functional effects of a c-kit tyrosine inhibitor on guinea-pig and human detrusor. BJU Int. 2006;97:612–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bycroft JA, Craggs MD, Sheriff M, Knight S, Shah PJ. Does magnetic stimulation of sacral nerve roots cause contraction or suppression of the bladder? Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:241–245. doi: 10.1002/nau.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi BR, Salama G. Simultaneous maps of optical action potentials and calcium transients in guinea-pig hearts: mechanisms underlying concordant alternans. J Physiol. 2000;529:171–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson RA, McCloskey KD. Morphology and localization of interstitial cells in the guinea pig bladder: structural relationships with smooth muscle and neurons. J Urol. 2005;173:1385–1390. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000146272.80848.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drake MJ, Gardner BP, Brading AF. Innervation of the detrusor muscle bundle in neurogenic detrusor overactivity. BJU Int. 2003;91:702–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ethans KD, Nance PW, Bard RJ, Casey AR, Schryvers OI. Efficacy and safety of tolterodine in people with neurogenic detrusor overactivity. J Spinal Cord Med. 2004;27:214–218. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2004.11753751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson DR, Kennedy I, Burton TJ. ATP is released from rabbit urinary bladder epithelial cells by hydrostatic pressure changes—possible sensory mechanism? J Physiol. 1997;505:503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.503bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashitani H, Yanai Y, Suzuki H. Role of interstitial cells and gap junctions in the transmission of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in detrusor smooth muscles of the guinea-pig urinary bladder. J Physiol. 2004;559:567–581. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanai A, Roppolo J, Ikeda Y, Zabbarova I, Tai C, Birder L, Griffiths D, de Groat W, Fry C. Origin of spontaneous activity in neonatal and adult rat bladders and its enhancement by stretch and muscarinic agonists. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1065–F1072. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00229.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruse MN, Bray LA, de Groat WC. Influence of spinal cord injury on the morphology of bladder afferent and efferent neurons. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;54:215–224. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00011-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills IW, Drake MJ, Greenland JE, Noble JG, Brading AF. The contribution of cholinergic detrusor excitation in a pig model of bladder hypocompliance. BJU Int. 2000;86:538–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schurch B, de Seze M, Denys P, Chartier-Kastler E, Haab F, Everaert K, Plante P, Perrouin-Verbe B, Kumar C, Fraczek S, Brin MF. Botulinum toxin type a is a safe and effective treatment for neurogenic urinary incontinence: results of a single treatment, randomized, placebo controlled 6-month study. J Urol. 2005;174:196–200. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000162035.73977.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suchyna TM, Nitsche JM, Chilton M, Harris AL, Veenstra RD, Nicholson BJ. Different ionic selectivities for connexins 26 and 32 produce rectifying gap junction channels. Biophys J. 1999;77:2968–2987. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugaya K, de Groat WC. Influence of temperature on activity of the isolated whole bladder preparation of neonatal and adult rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R238–R246. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.1.R238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugaya K, de Groat WC. Inhibitory control of the urinary bladder in the neonatal rat in vitro spinal cord-bladder preparation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;138:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00468-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sui GP, Coppen SR, Dupont E, Rothery S, Gillespie J, Newgreen D, Severs NJ, Fry CH. Impedance measurements and connexin expression in human detrusor muscle from stable and unstable bladders. BJU Int. 2003;92:297–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sui GP, Rothery S, Dupont E, Fry CH, Severs NJ. Gap junctions and connexin expression in human suburothelial interstitial cells. BJU Int. 2002;90:118–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szell EA, Somogyi GT, de Groat WC, Szigeti GP. Developmental changes in spontaneous smooth muscle activity in the neonatal rat urinary bladder. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R809–R816. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00641.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran Van Nhieu G, Clair C, Bruzzone R, Mesnil M, Sansonetti P, Combettes L. Connexin-dependent inter-cellular communication increases invasion and dissemination of Shigella in epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:720–726. doi: 10.1038/ncb1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Aa F, Roskams T, Blyweert W, Ost D, Bogaert G, De Ridder D. Identification of kit positive cells in the human urinary tract. J Urol. 2004;171:2492–2496. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125097.25475.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe T, Yokoyama T, Sasaki K, Nozaki K, Ozawa H, Kumon H. Intravesical resiniferatoxin for patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Int J Urol. 2004;11:200–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2003.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto Y, Fukuta H, Nakahira Y, Suzuki H. Blockade by 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid of intercellular electrical coupling in guinea-pig arterioles. J Physiol. 1998;511:501–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.501bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao HB. Connexin26 is responsible for anionic molecule permeability in the cochlea for intercellular signalling and metabolic communications. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1859–1868. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]