Introduction

What do physicians do to most satisfy their patients? And how do they maintain a state of well-being in their clinical practice? The answers to these questions have unfolded in a series of studies over seven years.

Recent Studies

Pilot Study

In 2001, a pilot study was conducted in Portland, OR to explore the communication practices of physicians who scored highest on the Art of Medicine (AOM) Patient Survey (see Sidebar: Art of Medicine Attributes), five years post implementation. The 2002 published report cited five core practices that emerged from 21 top-performing physicians: courtesy and regard, attention, listening, presence, and caring.1

Art of Medicine Attributes.

In the Art of Medicine survey seven attributes of clinicians' communication skills are assessed with the following questions:

How COURTEOUS and RESPECTFUL was the clinician?

How well did the clinician UNDERSTAND your problem?

How well did the clinician EXPLAIN to you what he or she was doing and why?

How well did the clinician LISTEN to your concerns and questions?

Did the clinician SPEND ENOUGH TIME with you?

How much CONFIDENCE do you have in the clinician's ability or competence?

Overall, how satisfied are you with the SERVICE you received from the clinician?a

a Personal communication from: Weiss K. Measuring the reliability and validity of the Art of Medicine Survey. Denver (CO): HealthCare Research, Inc. 2001 Jan.

Garfield Study

This communication research continued in 2004 as part of two-region Garfield Memorial Fund research: MD-Patient Communication Study, part of the Clinician-Patient Communication Research Initiative.2 Researchers have consistently found the top predictors of overall patient satisfaction are the quality of the physician-patient relationship and of the contributing communications,3 yet there is limited understanding of the range of specific interaction behaviors associated with positive and negative patient perceptions and reactions.

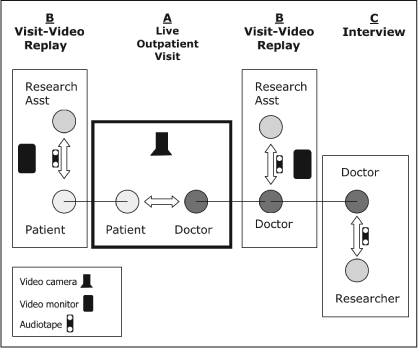

The researchers conducted a naturalistic, observational study of 61 physicians (high, medium, and low AOM patient satisfaction scores) and 192 of their patients: A) by videotaping their live outpatient visit; B) by privately audiotaping patient and physician reactions on viewing their visit tape; and C) by a confidential interview with the highest of the performing physicians (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Research Model

The most important findings, of three reported subset analyses4–6 are summarized next.

Three Minutes More—The first analysis found that highly satisfied patients' perceive visit time with their physicians to be three minutes longer (22 minutes) than actual visit time (19 minutes).4

Listening and Explaining—In the second analysis, the most prevalent communication practice themes—identified by both physicians and patients—were: physician explanation skills and listening skills.

The Patient's Story—In the third analysis, the two most important practices—those exhibited by the highly satisfying physician group—were: attention to the patient's agenda, and drawing out the patient's story. The physicians focused on the patient's needs rather than primarily on clinical issues or visit management. Drawing out the patient's story, through active listening, included eliciting the patient's fears and concerns.6

Methodology

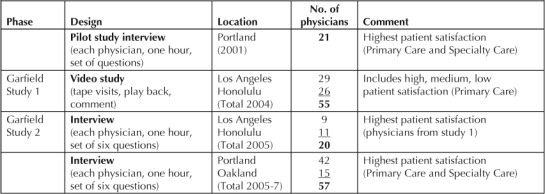

In the final phase of the Garfield research study (see Table 1), a standardized, six-question set was posed, in semi-structured, 60-minute interviews, to 77 of the highest-performing physicians on the AOM patient survey, including: 20 of the highest performers (top 5%) in the Los Angeles and Honolulu groups; 42 of the highest-performing physicians in Portland, OR, and 15 in Oakland, CA. These interviews were audiotaped with permission, transcribed and coded for patterns. The Portland and Oakland physicians represented 16 disciplines—Cardiology, Family Medicine, General Surgery, Infectious Disease, Internal Medicine, Immunology, Nephrology, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Oncology, Orthopedics, Ophthalmology, Otolaryngology, Pediatrics, Pulmonary Medicine, Psychiatry, and Urology.

Table 1.

Study populations

Results

This section first briefly summarizes the results from two of the six interview questions, then details a third question—on well-being—citing 21 physician comments that illustrate five identified realms.

Question One: “Doctor is Part of the Medicine”

Do you feel that your relating to your patients is an important part of your treatment of their medical condition? In other words, that, as a doctor, you are part of the medicine, or that you are the medicine?7

Results

All of the physicians agreed that, as doctors in a trusting relationship with their patients, they themselves are “part of” the medicine in all instances; and 90% agreed that they “are” the medicine in some circumstances. Physicians described one or more of several activities that qualify as “medicine” and are a required part of medical treatment to heal illness and improve physical condition, including: connection, listening, reassurance and support, touch, knowledge, explanation and education, understanding, insight.8

Verbatim

Here is an example of the extent of the therapeutic effect of this medicine:

Dr Smith said, “I had a patient last week who said to me, ‘Dr Smith, I've been thinking about coming in so many times since last year. When I would feel bad and be worried—think maybe I'm dying—and I'd say to myself, “You just think about Dr Smith,” and I would feel better.’”

Dr Smith said, “That blew my mind. I've always known for myself that feeling that I've got a great doctor, who's there for me even if I don't see them, gives me a sense of physical well-being. I can't explain that, but I experience that. And when that patient said that to me, that just knocked my socks off. ‘I just visualize you,’ he said, ‘and I feel better.’” (General Internist)

Question Two: “Doctor Creates Therapeutic Effect”

Do you believe, in the setting of a visit, that you, as a doctor, can create a therapeutic moment for your patient? In other words, that what you say, or how you say it, or your connection with your patient, has a treatment effect?

Results

All of the physicians endorsed this statement. They differed only on what set of activities were most important and most effective for them.9

Verbatim

As one high-performing physician said:

“Oh absolutely. These office visits are more than just reviewing factual things: they are part of the healing, connecting, and relationship process; all of which goes into making people better. Not all disease can be cured but most disease can be made better, either better understood or better tolerated or people can cope with things better and the office visit is a part of that process. The better connection you make, the easier the habit.” (Obstetric/Gynecologist)

Question Three: “Doctor Well-Being”

Do you feel that your sense of well-being as a doctor is related to how you practice medicine with your patients?

Results

All physicians agreed that how they practice medicine with their patients is related to, and improves, their own sense of well-being.10 These interview narratives provide deep, coherent learning in five realms:

What physicians derive from patient interactions

Their awareness of their state of well-being

Their personal and professional sense of self

The effect of physicians' well-being on patient interactions

Physician's self-care practices.

Verbatims

- What Physicians Derive from Patient Interactions

- “The time I spend with patients is the best time I spend all day. The time I spend in my office dealing with stacks of paperwork and administrative stuff, is the stuff that grinds me down and sends me home feeling depressed at times.” (General Internist)

- “The emotion of interacting with a patient, and the satisfaction I derive from that, is what makes me come to work. It's what makes me want to work.” (Family Physician)

- “I have much more of a sense of well-being from interactions with my patients than I used to. I was trained since I was in medical school that all this connection is just draining your energy—right? It's burning me out. And so I assumed that was happening, and was why I had energy issues—and thought I'm not going to have the energy to deal with my kids tonight. So, once a mentor definitively changed my frame of mind about that—that it could be satisfying—then I was able to notice, yeah, there is something that's draining about connection with patients—it does require energy—but there's also something that's nourishing about it, and now I have so much more satisfaction. I love seeing patients now. I did before, but now it's just something special. It really is. It is nourishing.” (Cardiologist)

- “Yes, I certainly do and that's a big part of my life. I think also how I interact with my coworkers and how I interact with my friends outside of medicine, all of that is part of the same thing. I just basically like interacting with people. I like getting into people's heads. I like getting into what their goals are, what their expectations are out of life. To me that's very rewarding in general.” (General Surgeon)

- Physicians' Awareness of their State of Well-Being

- “The times I feel I'm at my best are the times when I'm working the hardest, but I feel most rewarded, and my own well-being or mood is at its highest because I feel like I am doing the things that I was trained to do, that I'm making a difference, and that I'm connecting with people.” (Psychiatrist)

- “Cleaning out your in-basket is maybe a feeling of accomplishment, but it's not a feeling of well-being. I think it's definitely the patient interaction for me.” (Family Physician)

- “To me the biggest reward of my practice is the shopping bag full of patient thank-you cards and Christmas cards that I get. To me, that's basically almost worth more than money to have that kind of recognition. And I have a sense of connection. To be fairly highly rated in the patient satisfaction scores, I think that's all about connection and that's all about a two-way interaction with the patients and I think that's what's rewarding for both them and me in these kinds of interactions.” (General Surgeon)

- “I don't consider myself necessarily a very emotional person. But, when I see patients, and can feel like wow they're really struggling here, it does trigger an emotional response—that I think I sometimes choose to ignore because it's painful for me to feel that. We weren't trained to connect that way. But, as I think back over my experience with the patients I've cared for, so many are not necessarily looking for medications and treatments, they're really looking for relationships and the connection with someone who can at least empathize with their situation or their plights or the circumstances in their lives. To at least acknowledge that: “Yeah, it's hard. It's a difficult situation for you.” And to be, I don't know if reassured is the right word, but to say, “I wish things were different,” or “I wish I could do something differently here to help you.” I think, for patients, empathy is something that connects the relationship with their physician.” (General Internist)

- “I know that at times when I am distracted, disturbed, I find it very difficult to be present, very difficult to invest. If you just let go of your own problems when you walk into that room, you actually recognize that you feel better. Done right, the process is good for you—learning to let go of stuff we choose to hold on to and we don't have to is often the first step to be well. (Oncologist)

- “My sense of well-being is absolutely supported by the interactions that I have with the patients. If I have unhappy patients it makes for an uncomfortable and unhappy time in the office. The difference between Surgery and Primary Care is that the people who come to see us are often afraid, but it's something that I have a fairly simple solution for and when they leave they are going to be well. I wouldn't enjoy what I do nearly so much if I only had ten minutes to see someone. I have a lot more respect for the medical people that are in this group, than I do looking at my own situation, because I feel I have an unfair advantage, and our ability tends to be a sort of bond that forms from the operation.” (General Surgeon)

- Physicians' Personal and Professional Sense of Self

- “This whole line of thought is interesting to me just because I feel that medicine is so much more than what we learned in medical school—the nuts and bolts and knowledge we all had to absorb—but medicine is so much more than that—its personality, its spirituality (for me), reminding yourself to be present for that person, it's satisfying. I feel like I get something from my visits with my patients. I don't know what it's going to be. It might be that feeling of satisfaction or it might be learning something. I think that's why I like it—it's almost nourishing in a way.” (General Internist)

- “Yes I certainly do derive a sense of well-being from patient interactions. I have a bad evening at home or in the morning and I'll go to work and see several patients and have a good interaction, it changes my whole outlook on life. It really is important. In general, my home life is wonderful, but it can be completely turned around by experiences at work, good or bad actually. My interaction with patients is very gratifying. However, the environment in which I'm having to do it is getting harder and harder to deal with, because the pressure is on me to see more people, or to do the coding, or the electronic medical record, or one more little thing that “doesn't take any time.” It takes away from my time with my patients and that upsets me. I've avoided committees and other things that physicians use to dilute patient care a bit. As a result I have more patients than I can take care of. I need to balance that out. My overall sense of well-being is fine, but I'm getting kind of tired of being interrupted.” (General Surgeon)

- “I have the luxury of being a subspecialist where I get to focus on one aspect of a patient's health, rather than having to simultaneously manage a number of chronic conditions for which there may not be a great answer. And I have the luxury of having a diagnosis for which there is a good treatment. A happy patient makes for a happy doctor. I think that part of the reason for my successful relationships with patients is due to the success of the treatment. I do feel very fortunate from a professional standpoint that this is what I do for a living, because I do feel rewarded, and I do think that my emotional and mental well-being as a physician couldn't really be higher from a mental standpoint.” (Orthopedist)

- The Effect of Physicians' Well-Being on Patient Interactions

- “It's the domino kind of thing where they give you positive feedback, and then you feel better, and do better, and then they give you more positive feedback.” (General Internist)

- “They had a training program for professionals to teach them how to hold cancer retreats. My wife and I went there. One of the things they had people do, which I sometimes ask people to do, is write poems about their illness. It's a way that people can access some deep stuff, and then, as their doctor, it's amazing the poems people write. And knowing them as their doctor, and then reading the poem they wrote, it was such a great way to understand them better. Why they wrote this particular thing—it's not about your dying, it's about what you do before you die. I think it's good training to help doctors understand who they are.” (Oncologist)

- “The interactions I get with patients is the big part of my day. I get a charge out of having somebody sad, smile; of having a kid that curls up Mom's lap and refuses to have anybody look at them, but by the third visit is giving me high fives. It's good for my self worth and my ego when I realize that I'm not the best surgeon in the medical group by far, but patients or parents will say, ‘I want you to operate on my family. I want you to do this.’ It's my interactions with them that make them want to do that.” (Otolaryngologist)

- “Sometimes I get into a frustrated situation with a patient that just has too many issues to deal with in a single visit. I carry that with me sometimes for the whole day. That's one of the reasons I work hard to have good patient interactions. I like feeling good. If I feel good, they feel good, then I feel good. I'm jazzed up.” (General Internist)

- Self-Care Practices

- “I like to take care of myself and make sure I'm feeling strong. However, it's been one of the biggest challenges for me to learn how to comfort myself and not be overwhelmed by stuff. That's the hardest part of maintaining my well-being. The physical well-being—being healthy and all that—I try to be healthy, but the emotional well-being—it's been hard. We're not really encouraged to reach out to other people. If you want relevance and you want connection, then you have to feel the wounds too. You can't get both. You can't have doctors feel very connected with their patients and then get wounded and not have any way to heal that.” (Oncologist)

-

“I don't think, ‘Well, this is my eight hours here in the clinic and I put on my doctor hat while I'm here and when I'm home I just don't deal with medicine.’ For colleagues that I've worked with who have had problems with patient relationships, there has always been an undertone of resentment—either resentment for the patient or resentment for their inability to fix the problem. They take it very personally that they aren't able to fix that person. None of us may be able to. Or, they resent somebody making a demand on them that they perceive as out of their routine, or their schedule. It's just how we choose to live that reality. Nothing ever really changes; it's just our perception of it.I do take a few minutes every day to just remind myself that if it's busy and I'm feeling overwhelmed and I tap into that, recognize it, I'll meditate. When things are most out of control is when I'm most likely to take two or three minutes, just close the door, and chill, get things in perspective, and then get back at it. Just putting in perspective how good things are for me, I'm really blessed. Rarely is there anything here that's worth getting stressed out over or burned out over.” (Urologist)

- “There are always admonitions about how everybody should get a life, etc. I have a wonderful relationship with my wife but a lot of my real soul comes from what I do in my office. I wouldn't give up my practice for anything. I have had a lot of experience with several of the health systems in the area and all of them seem to do the same things with primary care. They get the bean counters in and they have to be efficient—that means primary care clinicians have less and less control over their schedules. It's just plain a loss of any sense of autonomy. That's what we are losing. There is this sense of ‘I want every minute that you have to be occupied with who I tell you is going to occupy it.’” (Psychiatrist)

- “The relentlessness of the pace is somethingI struggle with. The only way I can continue to do this business, and to give what I need to give to my patients, and want to give to my patients, is if I take care of myself in a way that allows me space, balance, to be reenergized—to eat well, sleep well, exercise, do my art, cook, garden, and things that completely use a different part of my brain. Obviously, a lot about the work itself is energizing.” (Infectious Disease)

“Cleaning out your in-basket is maybe a feeling of accomplishment, but it's not a feeling of well-being. I think it's definitely the patient interaction for me.”

“… patients or parents will say, ‘I want you to operate on my family. I want you to do this.’ It's my interactions with them that make them want to do that.”

Discussion

Together, the four Garfield Memorial Fund studies described offer summary learnings.

Patient satisfaction with communication in a visit expands patients' perceptions of time. Having an additional three minutes in a visit could allow you to have tea and chat, such is the feeling of space that extra time creates.

The doctors, whose patient's are most satisfied, describe needing to listen well enough for their patients to feel heard, and to be heard, so that the patient-desired explanation creates understanding and confidence. It reassures. The practices that these highly satisfying physicians engaged in were: attention to setting an agenda; and drawing out, and listening to the patient's story. These doctors focused on their patient's needs rather than primarily on clinical issues or visit management. Drawing out the patient's story, through active listening, included eliciting the patient's concerns and fears. This is a great context for improved diagnosis and treatment. The findings are also consistent with Kaiser Permanente's efforts to train physicians in communication skills using the Four Habits approach.11

Doctor is Medicine

In the context of a trusting relationship with their patients, all high-performing physicians agreed that, as physicians they are “part of” the medicine in all instances; and 90% agreed that they “are” the medicine in some circumstances. They describe one or more of several empathetic activities that qualify as “medicine” and are a required part of medical treatment, including: respect, attention and presence, listening, connection, reassurance and support, touch, knowledge, explanation and education, understanding, insight.7

The point is that this visit interaction is not just a mechanical exchange of information. It is also a transpersonal encounter—people relating their story and building relationships. The activities or states that are medicine are not just a toolbox of items to dispense, but the person who is the doctor is medicine for the patient.

Medicine is Therapeutic

The often-cited statistics that 60–80% of primary care visits are for reassurance of psychosocial concerns12–15 undermines the potentially powerful therapeutic treatment effect that connection, reassurance, explanation, understanding, and other subjective activities can have. The physicians we interviewed believed that these activities or states helped to heal a patient's illness and treated their medical condition—that who the doctor is, and what the doctor says and does in the visit is therapeutic, either independent of, or in complement to, prescribed medications and other treatments.

Well-Being is Enhanced

If physicians practice this way, what effect does it have on them? Does it burn them out? Or does it nourish them?

With short- and long-term relationships, as the necessary foundation,3 interaction often produces well-being for both patient and doctor. Physicians described that when they experience patient interactions where they feel part of the medicine, it is responsible for their sense of feeling valued, making an important contribution, making a difference, and creating personal and professional well-being.

Physicians described five components that integrate to enhance well-being: 1) deriving something from patient interactions; 2) awareness of their state of well-being; 3) personal and professional sense of self; 4) personal well-being has an effect on their patient interactions; and 5) physicians practice self-care.

Physicians' interaction and connection with patients, though requiring energy, focus, and tolerance is nourishing, energizing, and brings fulfillment and meaning. It prevents burn-out, which appears to grow out of mechanized work, often menial, squeezed of human emotion, meaningful moments, and personal conversation. Rather than draining your energy—as physicians, including me, were taught in medical school, and re-enforced by a medical culture rooted in this unexamined belief—physicians find nourishment in their patient interactions. It is often a simultaneously therapeutic moment for both physicians and patients. Without these interactions, physicians struggle to sustain themselves when acting totally objective, and tending solely to the task at hand, rather to the person they are with.

Physicians are aware of their state of being—well-being or distress—in their practice, and with their patients. They are aware of connection and meaningful moments.

Physicians' personal and professional selves are closely related, affect each other, and often work simultaneously to achieve the goals of each. A person is delighted to be in the professional role of a doctor and help people become aware of their state of physical and emotional health, and to understand what they can do to effect any necessary change.

Physicians' well-being affects their patients, as one doctor said, in a domino effect of positive feedback loops.

Because it can be hard to continually engage patients, especially given the technical and time-constrained environment, physicians take care of themselves, and care for themselves, in a variety of ways and practices, such as: taking a moment and a deep breath, meditation, being with their families, reflecting on their life, writing poetry. They describe these practices as necessary to maintain or return to a state of well-being.

Creation of well-being is part of the psychological-physiological mechanism to maintain human homeostasis.

Conclusions

As our use of, and dependence on, medical technology increases, knowing that the physician is medicine for the patient—and that that creates high patient satisfaction—affirms the value of developing a good relationship, and offers a potent, available alternative to some testing and medications, especially for patients with chronic diseases.8

With primary care in crisis nationally,16 and specialists increasingly procedure focused, understanding the nature of physician satisfaction, especially in relationship to patient satisfaction, is of the greatest importance to the sustainability of the highest-quality medical care and service. Physicians' greatest stress is the lack of time to create and maintain patient relationships, often associated with the increasing tasks and technology demands. Their greatest reward is patient interaction and connection in the context of their clinical practice—getting to know people and helping them.

Physicians note the benefit of communication education in improving their satisfying interactions with patients—there are ways to improve, and ways to transform. Medical education, the format of the office visit, and leadership expectations must optimize and emphasize the essential value of subjective empathetic activities and states in creating the highest patient satisfaction and the most effective medical treatment outcomes.9

Part two of this editorial will appear in the Winter 2009 issue of The Permanente Journal, and is entitled: “‘Can All Doctors Be Like This?’ Ten Stories of Transformation of Physicians Who Satisfy Their Patients Best.”

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank his co-researchers: Elizabeth Sutherland, ND, National College of Natural Medicine, Portland, OR; Nancy Vuckovic, PhD, Intel Corporation (during the study: Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest); Karen Tallman, PhD, The Permanente Federation, Oakland, CA; Richard Frankel, PhD, Indiana University School of Medicine; John Hsu, MD, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA; Sue Hee Sung, MPH, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA; and Terry Stein, MD, The Permanente Medical Group, Oakland, CA.

References

- Janisse T, Vuckovic N. Can some clinicians read their patients' minds? Or do they just really like people? A communication and relationship study. Perm J. 2002 Summer;6(2):35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E, Wing A. The Sydney H Garfield legacy—a tradition of caring. Perm J. 2003 Winter;7(1):42–5. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel RM. Relationship-centered care and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Nov;19(11):1163–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung SH, Price M, Tallman K, et al. Ambulatory care visits: squeezing 22 minutes into a 19-minute visit? [poster abstract] p. 2004. The 10th Annual HMO Research Network Conference, Dearborn, MI.

- Sung SH, Price M, Frankel R, et al. Physician and patient perspectives on clinician-patient communication during clinic visits: Do you see what I see? [poster abstract] 2005. The 11th Annual HMO Research Network Conference, Sante Fe, NM.

- Tallman K, Janisse T, Frankel R, Sung SH, Krupat E, Hsu TJ. Communication practices of physicians with high patient-satisfaction ratings. Perm J. 2007 Winter;11(1):19–29. doi: 10.7812/tpp/06-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balint M.The doctor, his patient, and the illness. Millennial Edition. Oxford (UK): Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Janisse T, Sutherland L, Vuckovic N, et al. Relationship with a doctor who is medicine: practices of the highest performing physicians by patient survey [abstract presentation] The AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting; Seattle, WA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Janisse T. Empathy: In a moment, a powerful therapeutic tool. Perm J. 2006 Fall;10(3):2. doi: 10.7812/tpp/06.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janisse T, Sutherland E, Vuckovic N, et al. Relationship of a doctor's well-being to interactions with patients: Practices of the highest-performing physicians by patient survey [abstract presentation] 2008. The 14th Annual HMO Research Network Conference; Minneapolis, MN. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krupat E, Frankel RM, Stein T, Irish J. The Four Habits Coding Scheme: validation of an instrument to assess clinicians' communication behavior. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Jul;62(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosahl K. Building primary care behavioral health care systems that work: A compass and a horizon. In: Cummings NA, Cummings JL, Johnson JN, editors. Behavioral health in primary care: A guide for clinical integration. Madison (CT): Psychosocial Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Fireman B, Weissman MM, et al. Mental disorders and disability among patients in a primary care group practice. Am J Psychiatry. 1997 Dec;154(12):1734–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Jackson CA, Meredith LS, Camp P, Wells KB. Prevelance of co-morbid anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5(1):27–34. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel R, Quill T, McDaniel S, editors. Biopsychosocial Care. Rochester (NY): University of Rochester Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T. Primary Care—Will It Survive? New Eng J Med. 2006 Aug 31;355(9):861–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]