Deletion of follistatin-303 and -315 isoforms results in increased primordial follicle number through reduced apoptosis as well as increased germ cell number at birth.

Abstract

Follistatin (FST) is an antagonist of activin and related TGFβ superfamily members that has important reproductive actions as well as critical regulatory functions in other tissues and systems. FST is produced as three protein isoforms that differ in their biochemical properties and in their localization within the body. We created FST288-only mice that only express the short FST288 isoform and previously reported that females are subfertile, but have an excess of primordial follicles on postnatal day (PND) 8.5 that undergo accelerated demise in adults. We have now examined germ cell nest breakdown and primordial follicle formation in the critical PND 0.5–8.5 period to test the hypothesis that the excess primordial follicles derive from increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis during germ cell nest breakdown. Using double immunofluorescence microscopy we found that there is virtually no germ cell proliferation after birth in wild-type or FST288-only females. However, the entire process of germ cell nest breakdown was extended in time (through at least PND 8.5) and apoptosis was significantly reduced in FST288-only females. In addition, FST288-only females are born with more germ cells within the nests. Thus, the excess primordial follicles in FST288-only mice derive from a greater number of germ cells at birth as well as a reduced rate of apoptosis during nest breakdown. These results also demonstrate that FST is critical for normal regulation of germ cell nest breakdown and that loss of the FST303 and/or FST315 isoforms leads to excess primordial follicles with accelerated demise, resulting in premature cessation of ovarian function.

Follistatin (FST) is a widely expressed protein (1) that was originally isolated from gonadal fluids based on its ability to regulate FSH biosynthesis (2) through its ability to antagonize the TGFβ superfamily member activin (3). Like FST, activin was originally purified from gonadal sources (4) and demonstrated to have important actions in regulating both male and female gonadal function (5, 6) in addition to its ability to stimulate FSH biosynthesis in the pituitary (7). More recent analysis demonstrated that FST also antagonizes structurally related TGFβ superfamily members such as myostatin and GDF11 with a slightly lower affinity and to a much lesser degree, bone morphogenetic proteins 6 and 7 (8, 9). Three protein isoforms are derived from the Fst gene that vary in length as well as in their ability to bind to cell surface proteoglycans (3). The three isoforms have roughly equal binding affinity for activin but the shorter FST288 isoform has enhanced ability to regulate activin derived from autocrine or paracrine sources (9). The longer FST315 isoform has an acidic tail that inhibits cell-surface binding and is thus found primarily in the circulation while the intermediate FST303 isoform has reduced cell-surface binding activity and has only been identified in gonadal fluids and extracts (9, 10). The global Fst knockout mouse is neonatally lethal, demonstrating the importance of Fst but also limiting discovery of Fst's roles in the adult (11). However, conditionally deleting Fst from granulosa cells altered follicle development and reduced overall fertility of females indicating that FST regulation of ovarian activin is critical for normal reproduction in females (12).

Premature ovarian failure (POF), a condition characterized by cessation of ovarian activity before the age of 40, affects nearly one percent of reproductive age women (13). In about 30% of POF patients, this condition is caused by defined genetic alterations, including mutations in FoxL2, deletions within the x-chromosome, and fragile x chromosome mutations (13). Identification of the etiological basis for POF in the remaining 70% of patients is a pressing clinical need because relatively few treatment options have been developed for these women due to their generally poor response to exogenous gonadotropins and paucity of remaining viable oocytes (14). One attractive hypothesis for the cause of POF in women without a known genetic etiology is that polymorphisms in genes involved in critical pathways for primordial follicle formation or survival, coupled with environmental insults that exacerbate these alterations, lead to a reduced initial primordial follicle pool and/or to accelerated decline in primordial follicle number. This would ultimately decrease the reproductive lifespan of affected females by reducing the primordial follicle pool below the critical threshold necessary to maintain ovarian activity, a mechanism that has been proposed to account for at least some POF cases (15).

Primordial follicles are formed during gestation in humans but after birth in rodents in a process that involves dissolution of germ cell syncytia or nests that form during germ cell mitosis (16). The process of germ cell nest breakdown involves migration of somatic pregranulosa cells into the nest and simultaneous disruption of the inter-oocyte bridges through apoptosis of individual oocytes. The pregranulosa cells then surround the remaining oocytes to form primordial follicles that constitute the resting stock of gametes for the entire reproductive lifespan of mammalian females (16). Thus, any alteration in this process might lead to reduced primordial follicle pool size and POF.

A number of recent studies have identified important pathways regulating the processes of follicle formation and primordial follicle activation, the sum of which influences the size of the primordial follicle pool over a female's reproductive lifespan. Estradiol signaling is critical for inhibiting nest breakdown until birth in rodents (17) and may regulate this process in higher mammals as well. Foxo3 is a critical transcription factor that has been shown to regulate activation of primordial follicles and deletion of this factor results in complete loss of primordial follicles and ovarian failure in mice (18). In normal females, Foxo3 is regulated by AKT signaling such that upon phosphorylation, Foxo3 is removed from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, allowing follicle development to resume (19). Activin administration to newborn female mice results in an increased primordial follicle pool size but these extra follicles are lost by puberty (20), demonstrating that the activin signaling pathway might be a critical determinant of primordial follicle number. In fact, estradiol administration can decrease activin mRNA and protein biosynthesis (21), suggesting that one or more of these pathways may interact to control the process of germ cell nest breakdown.

We have previously demonstrated that mice expressing only the FST288 isoform are subfertile and share a number of features with human POF including irregular cycles, FSH resistance, accelerated loss of primordial follicles, and early termination of ovarian activity (22). Paradoxically, FST288-only female neonates have a greater number of primordial follicles at postnatal day (PND) 8.5 compared with wild-type (WT) littermates, but this pool is depleted more rapidly. In the present study we tested the hypothesis that increased proliferation or decreased apoptosis during germ cell nest breakdown in FST288-only females is responsible for the enlarged primordial follicle pool. We found that FST288-only mice at PND 0.5 had more germ cells in their ovaries compared with WT females and the difference in germ cell numbers between the genotypes was greater at PND 8.5 compared with PND 0.5, consistent with increased germ cell survival during germ cell nest breakdown contributing to this larger pool. Germ cell proliferation was extremely rare in neonatal FST288-only ovaries and could not account for the excess primordial follicles. However, germ cell apoptosis was significantly reduced in FST288-only females, and the process of germ cell nest breakdown was extended in time. Therefore, these results indicate that the increased primordial follicle pool in FST288-only mice derives from a combination of increased germ cell number at birth and reduced apoptosis during primordial follicle formation, suggesting that manipulating activin and/or FST activity could influence primordial follicle pool size. In addition, our results reveal that alteration of FST isoform expression leads to modifications in the follicle formation program resulting in an initially increased primordial follicle pool that is susceptible to accelerated depletion, resulting in a POF-like phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Animal treatment and tissue collection

Creation and characterization of the FST288-only mice and their reduced fertility has been previously described (22). The knock-in mutation was made on a mixed 129S4/SvJae × C57BL/6 background. All animal experiments were approved by the Baystate Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Individual breeding pairs were inspected daily, and the day when new pups were found was regarded as PND 0.5. Ovaries were collected on PND 0.5, 3.5, 5.5, and 8.5, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned as previously described (22).

Follicle counting

Procedures used for follicle identification and counting were previously described in detail (22). Briefly, paraffin embedded ovaries were sectioned at 4 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Oocytes/follicles were counted in every sixth section throughout the entire ovary. A correction factor (multiplied by 6) was used to determine total oocyte/follicle number for oocytes in germ cell nests and for primordial and primary follicles as previously described (22). If two or more germ cells were in direct contact with each other and as a group were surrounded by pregranulosa cells, we considered them to be localized within a nest.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) injection

PND 0.5 female mice were injected ip with BrdU (1 μg/g body weight). One day after BrdU injection the mice were killed and the ovaries were collected and processed as described above.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue staining and microscopy procedures were previously described (22). Neonatal ovaries were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde 4–6 h at room temperature and then embedded in paraffin. The tissue were cut at 4 μm and the slides were subjected to microwave antigen retrieval (10 mm citrate buffer; pH 6.4) for 30 min at 98 C. Sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 10 min and blocked with 5% normal donkey serum in PBS. The sections were incubated in 1st antibody diluted with 5% normal donkey serum in PBS for two hours at room temperature or overnight at 4 C, rinsed, and then incubated in EnVison + System-HRP labeled polymer antirabbit (Dako) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by DAB reagent (Dako) exposure for 2 min according to the manufacturer's instructions. The specimens were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with Cytoseal TM XYL (ThermoScience).

The following primary antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry and double immunofluorescence: Rabbit antimouse Vasa (DDX/MVH) antibody (Abcam, Cambridge MA; 1:100); Mouse antihuman Ki-67 (1:100), mouse antihuman cleaved-PARP-1 (BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA; 1:100); rat anti-BrdU (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation, Westbury NY; (1:100)), Rabbit anti-PSmad2/3 (1:50), Rabbit anti-PSmad1/5/8 (1:100), rabbit antimouse cleaved PARP-1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston MA; 1:100); rat antimouse germ cell nuclear antigen-1 (GCNA-1) IgM (generous gift from Dr. GC Enders) (1:500), and rabbit antimouse-FST (1:5,000), which was produced and validated as previously described (22).

Immunofluorescence

Four different double immunofluorescence methods were used: double immunofluorescence for BrdU or Ki67 and germ cell marker Vasa or GCNA-1, double immunofluorescence for TUNEL and Vasa, double immunofluorescence for GCNA-1 and FST or cleaved PARP-1, and Double immunofluorescence for FST and cPARP-1.

Double immunofluorescence for BrdU or Ki67 and germ cell marker Vasa or GCNA-1

The immunohistochemistry procedure was used through antigen retrieval, after which the sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBS. Slides were incubated with both primary antibodies (one proliferation marker and one germ cell marker) in the blocking serum overnight at 4 C or for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with appropriate sets of Tritc conjugated antibodies (1:100) or Alexa Fluor 568 goat antibody (1:500) and Fitc conjugated donkey antibodies (1:100) or Alexa fluor 368 goat antibody (1:500) for 60 min. After washing in PBS, sections were treated with DAPI and mounted in Fluorescent Mounting Media (Calbiochem).

Double immunofluorescence for TUNEL and Vasa

FragEL DNA Fragmentation Detection Kit (Calbiochem) was used with minor modifications of manufacture instruction. After application of TdT labeling reaction mixture, the sections were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS for 20 min at room temperature and then the Vasa antibody was applied in 5% of NGS with 0.005% Triton X for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the Tritc conjugated goat antirabbit second antibody was applied for 1 h, after which the tissues were treated with DAPI and mounted.

Double immunofluorescence for GCNA-1 and FST or cleaved PARP-1

Both GCNA-1 and FST or rabbit cleaved PARP-1 antibodies were applied for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with dylight-549–conjugated goat antirat-IgM antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the tissues were incubated with EnVison + System-HRP–labeled antirabbit polymer (Dako) for 30 min, washed with PBS again, and then exposed to the TSA Fluorescein detection system (PerkinElmer) according to manufacturer's instructions, after which they were stained with DAPI and mounted.

Double immunofluorescence for FST and cPARP-1

The FST antibody was applied overnight at 4 C. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with EnVison + System-HRP labeled antirabbit polymer for 30 min, washed with PBS again, and exposed to the TSA Cy3 system (Perkin-Elmer). The tissues were then treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 5 min followed by blocking with 5% NGS and exposure to mouse anti–cPARP-1 for 2 h at room temperature. After another wash, the sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min, washed with PBS, and incubated with ABC reagent for 30 min. Slides were then washed and exposed to the TSA Fluorescein system (Perkin-Elmer) and DAPI, and then mounted.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical comparisons of oocytes between genotypes and ages, the results were analyzed using unpaired Student's t test using Graph Pad Prism. A level of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Extended germ cell nest breakdown in FST288-only females

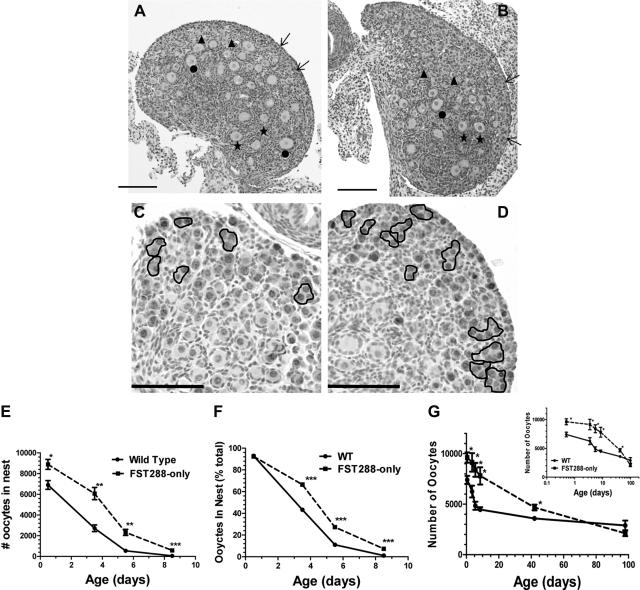

We previously reported that FST288-only females were subfertile with fewer preovulatory follicles as adults but more primordial follicles at d 8.5. However, this surfeit of primordial follicles had an accelerated rate of demise so that the numbers of primordial follicles was not different from WT at puberty and was reduced at all adult ages due, at least in part, to premature activation of these resting follicles (22). To determine the mechanism(s) accounting for these excess primordial follicles, we have now examined ovaries at more time points between birth and PND 8.5. At PND 0.5, nearly all germ cells in both WT and FST288-only ovaries were located within nests (Supplemental Fig. 1, A and B, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). However, by d 5.5, germ cell nest breakdown and primordial follicle formation was nearly compete in WT ovaries but approximately 30% of germ cells remained within nests in FST288-only ovaries, especially near the periphery of the ovary (Fig. 1, A and B; Supplemental Fig. 1, C and D). Immunohistochemical analysis for GCNA-1 was used to confirm germ cell identity, where intense nuclear staining was observed for germ cells within the nest and in primordial follicles, but decreased as the follicles matured (Fig. 1, C and D; Supplemental Fig. 1, E and F). Moderate levels of staining were also observed in oocyte cytoplasm of primordial follicles and germ cells remaining within the nest. Quantifying these results for PND 0.5, 3.5, 5.5, and 8.5 revealed that FST288-only mice have significantly more oocytes remaining within nests at all ages, both in absolute number and as the fraction of total germ cells (Fig. 1, E and F). Despite the increased germ cell number, however, the fraction of germ cells within the nest on d 0.5 is the same for FST288-only and WT ovaries indicating that the start of germ cell nest breakdown is not altered (Fig. 1F), Germ cell nest breakdown was nearly complete by PND 5.5 in WT ovaries but continued at least until PND 8.5 in FST288-only ovaries, indicating that the period of germ cell nest breakdown was extended in FST288-only mice.

Fig. 1.

Extended germ cell nest breakdown in FST288-only females. From four to six ovaries were used to count the follicle numbers in each day of each genotype. A, H and E staining of PND 5.5 WT ovary. The outer cortex contains a number of primordial follicles and oocytes still in the nest as well as primary and secondary follicles in the medulla. B, H and E stain of FST288-only ovary showing the number of germ cells remaining within nests is greater in FST288-only ovaries compared with WT. C, GCNA1 staining of PND 5.5 WT ovary confirming germ cell identity of cells within nests. D, GNCA1 staining of FST288-only ovary showing greater number of germ cells within nests compared with WT. E, Total number of oocytes remaining within the nest at PND 0.5–8.5 in both WT and FST288-only mice. Note that FST288-only ovaries have significantly more germ cells at PND 0.5 suggesting increased proliferation before birth. F, Same data as E but now expressed as percent of total germ cells. G, Total number of oocytes in each ovary regardless of stage at PND 0.5, 3.5, 5.5, 8.5, 42, and 98. Loss of germ cells is reduced in FST288-only ovaries compared with WT (20% vs. 40% respectively) during germ cell nest breakdown (up to PND 8.5), but this rate is greater at later ages leading to premature exhaustion of the primordial follicle pool before 1 year of age (22). Scale bar, 100 μm (A–D). *, P < 0.05.

To quantify the dynamic changes in germ cell number during this extended nest breakdown program in FST288-only ovaries, the total number of germ cells was ascertained at each age. In WT mice, the initial 7,500 germ cells on PND 0.5 was reduced by 40% at PND 5.5 but then decreased only slightly through PND 8.5 (Fig. 1G). In FST288-only ovaries, the rate of germ cell loss was reduced but extended in duration, so that the initially greater germ cell number of 9,500 at PND 0.5 decreased by 20% at PND 8.5 and germ cell number was significantly different from WT at all ages (Fig. 1G). Thus, germ cell number decreased by about 40% in WT but only 20% in FST288-only ovaries over the first 8.5 d, suggesting that the germ cell nest breakdown program was altered in FST288-only females, accounting in part for the increased number of primordial follicles on day 8.5. However, these results also demonstrate that FST288-only females have a greater number of germ cells in nests at birth, suggesting that germ cell proliferation may be enhanced or apoptosis reduced during embryologic development.

Germ cell proliferation during nest breakdown

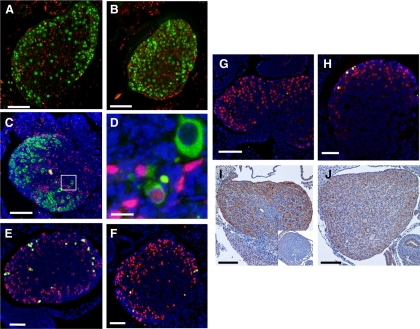

To determine whether the decreased rate of germ cell loss in neonatal FST288-only ovaries was attributable to altered proliferation or apoptosis, sections from ovaries at PND 0.5–8.5 were analyzed by double immunofluorescence with markers for germ cells and proliferation. Using Vasa or GCNA as germ cell markers and Ki67 to indicate proliferation, no evidence for germ cell proliferation was observed in either WT or FST288-only ovaries, although extensive somatic cell proliferation was observed (Supplemental Fig. 3, A–D). To verify this observation, females were administered BrdU at PND 0.5 and ovaries analyzed 24 h later. Using GCNA1 to identify germ cells, no double-stained germ cells were observed in ovaries from either genotype although somatic cells proliferated robustly (Fig. 2, A and B, and Supplemental Fig. 2, A and B, magnified version). However, using Vasa to identify germ cells in these BrdU injected ovaries, we found two double-stained germ cells in FST288-only ovaries out of > 7,500 germ cells counted on 50 sections from five different mice but none in WT ovaries (66 sections, five mice, > 9900 germ cells) (Fig. 2, C and D, and Supplemental Fig. 2, C and D, magnified version). These cells had smaller nuclei with less cytoplasm and were located neither within nests nor on the ovary surface, but rather isolated in the center of the ovary. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that germ cell proliferation is complete before, or just after, birth in rodents (16) but raise the possibility that extremely rare germ cell proliferation may occur in FST288-only ovaries after birth. Nevertheless, this small contribution is insufficient to account for the reduced germ cell loss during nest breakdown.

Fig. 2.

Proliferation, apoptosis, and FST in neonatal ovaries of WT and FST288-only mice. Four or five ovaries from each genotype at each age analyzed were used to detect proliferation or apoptosis. A, Proliferation in PND 1.5 ovary is shown by double immunofluorescence for BrdU (red) and GCNA-1 (green). No double-stained cells were detected, indicating that all proliferation was in somatic cells. B, Same staining in PND 1.5 FST288-only ovary. No double-stained cells were detected. C, Double immunofluorescence for BrdU (red), Vasa (green), and DAPI (blue) in 1.5-d FST288-only mouse. D, Enlargement of white box from C showing example of one of two double-stained germ cells observed of 7,500 examined. E, Apoptosis in germ cells of PND 0.5 WT ovary labeled for cleaved PARP-1 (green), GCNA-1 (red), and DAPI (blue). F, Same staining in 0.5-d FST288-only ovary showing reduced germ cell apoptosis relative to WT. G, Same staining in 5.5-d WT ovary, no apoptotic germ cells observed. H, Same staining in 5.5-d FST288-only ovary showing presence of apoptotic germ cells. I, Immunohistochemical staining for FST in PND 3.5 WT ovary. FST staining is prominent in oocyte cytoplasm, some stromal cells, some granulosa cells, and in ovarian surface epithelia. Intense stain is observed in some oocyte nuclei, but not all. Inset shows that staining disappears if FST antibody is preincubated with FST protein. J, FST immunohistochemistry in PND 3.5 FST288-only ovary. The staining pattern is similar to WT but less intense, although some oocyte nuclei are still intensely stained. Scale bar, 100 μm (A–C and E–J) and 10 μm (D).

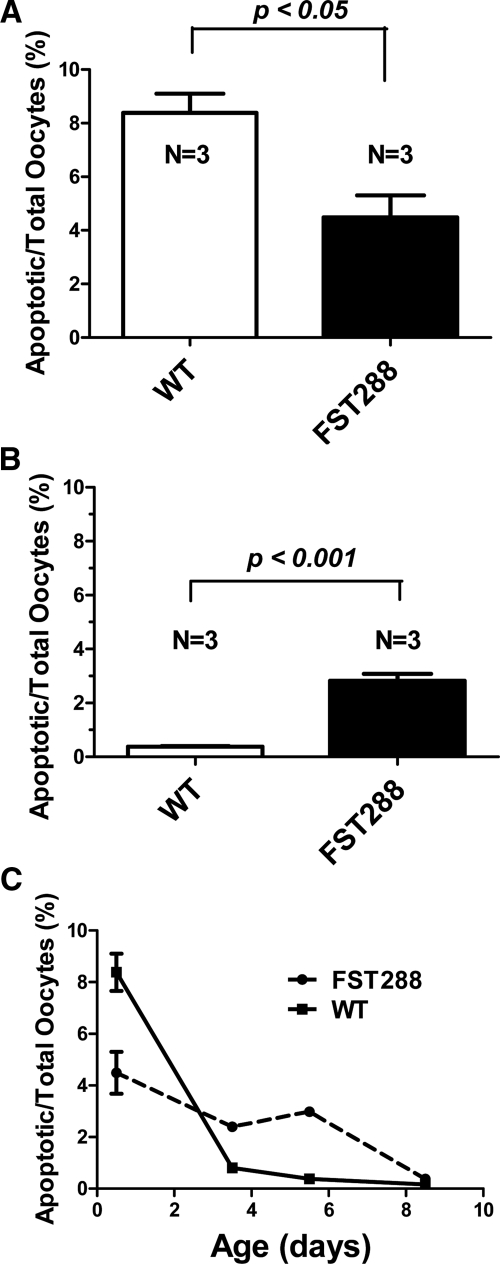

Germ cell apoptosis during nest breakdown

To determine whether oocyte apoptosis was altered during the extended nest breakdown period in FST288-only mice, double immunofluorescence analysis using several markers of apoptosis were used with two germ cell markers in neonatal ovary sections. Using GCNA to identify germ cells and cleaved PARP-1 (23) to identify apoptosis, approximately 8% of oocytes were double labeled in WT ovaries on PND 0.5 but only 4% in FST288-only ovaries (Fig. 2, E and F, and Supplemental Fig. 2, E and F; magnified version, Fig. 3A), suggesting that apoptosis was reduced in FST288-only ovaries. However, by PND 5.5, the situation was reversed with 0.5% apoptotic germ cells in WT ovaries while the 3% of germ cells were apoptotic in FST288-only ovaries (Fig. 2, G and H, and Supplemental Fig. 2, G and H; magnified version, Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained using TUNEL (Supplemental Fig. 4, A–F) to identify apoptosis. To quantify apoptosis rates in WT and FST288-only ovaries, apoptotic germ cells were counted at PND 0.5, 3.5, 5.5, and 8.5 using cleaved PARP1 to indicate apoptosis and expressed as a percent of total germ cells (Fig. 3C). Apoptosis was significantly greater in WT mice at PND 0.5 (P < 0.05) but decreased precipitously so that by PND 3.5, the number of apoptotic germ cells was significantly less than FST288-only ovaries (P < 0.05) and is nearly undetectable by PND 5.5 (Fig. 3C). Apoptosis was detectable in FST288-only ovaries through PND 8.5 and was significantly greater than WT mice between PND 3.5–8.5 (Fig. 3C). Thus, germ cell apoptosis was altered with the period of apoptosis being extended in FST288-only ovaries, consistent with the extended period of nest breakdown observed in these mice (Fig. 1, E and F) and the previously proposed mechanistic link between these two processes (16).

Fig. 3.

Quantitation of apoptosis staining in germ cells. A, Number of apoptotic cells as a fraction of total germ cells in PND 0.5 ovaries. Apoptosis in WT ovary is significantly greater than in FST288-only ovary. B, Number of apoptotic cells as a fraction of total germ cells in PND 5.5 ovaries. At this age, FST288-only ovaries have more apoptotic germ cells than WT. C, Apoptotic germ cells as a percent of total germ cells for PND 0.5–8.5 showing that apoptosis in WT ovaries is high but drops quickly and is almost undetectable by PND 5.5, whereas apoptosis in FST288-only ovaries starts lower but remains relatively constant through PND 5.5 and then decreases to nearly undetectable by PND 8.5. *, P < 0.05.

FST immunolocalization in germ cells of neonatal ovaries

We previously demonstrated that in addition to altered FST isoform expression, FST288-only mice also express less Fst mRNA and protein in adult ovaries (22). Because we now identified deviations in germ cell nest breakdown in early postnatal ovaries, it was critical to ascertain whether FST expression is similarly altered at this early time point. Immunohistochemical analysis for FST at PND 3.5 revealed relatively light staining in germ cell cytoplasm and darker staining in many germ cell nuclei and this pattern was not different between WT and FST288-only ovaries (Fig. 2, I and J, and Supplemental Fig. 5, C and D). FST staining was also observed in pregranulosa cells and ovarian surface cells as well as in some stromal cells (Fig. 2, I and J). Overall FST staining was reduced in neonatal FST288-only ovaries compared with WT ovaries. The same overall staining pattern and intensity was observed at the PND 0.5 and 8.5 time points as well (Supplemental Fig. 5, A, B, E, and F). These results suggest that reduced FST antagonism and consequent increased activin bioactivity may be a contributor to this altered germ nest breakdown phenotype.

FST immunolocalization with apoptotic markers in germ cells

To confirm that FST staining was indeed localized to the germ cell nucleus we performed double immunolabeling of GCNA-1 and FST. Some oocytes were identified that were positive for both FST and GCNA-1 (Supplemental Fig. 6A and 5F), confirming the localization of FST to germ cell nuclei. To determine whether nuclear FST in oocytes was related to altered apoptosis rates between the genotypes, double immunolabeling of FST and cleaved PARP-1 was performed. At PND 0.5 a few oocytes stained positive with both of FST and PARP-1 and this number increased by PND 5.5. However, there were many oocytes with either FST or cPARP1 staining, suggesting that the nuclear FST staining was not directly related to apoptosis (Supplemental Fig. 7, A–D).

Discussion

The pool of resting primordial follicles represents the entire reproductive potential of mammalian females and is established immediately after birth in rodents and during embryonic development in other mammals (16). Therefore, factors that influence the size or quality of this stockpile are critical determinants of reproductive potential. POF is thought to be caused by an accelerated rate of primordial follicle demise resulting in the size of this pool falling below a critical threshold necessary for normal ovarian function (15). As we previously reported, FST288-only females have reduced fertility including reduced litter size and frequency and premature cessation of ovarian activity (22). Follicle counting of ovaries from neonates and adults revealed that these mice initially have a larger number of primordial follicles at d 8.5 but that this pool is more rapidly depleted so that by puberty the size is equal to WT females and is reduced relative to WT mice at all adult ages. This latter finding suggests that premature primordial follicle demise is responsible for the early termination of reproduction in these mice, similar to human POF.

The studies described here were designed to determine the mechanism(s) responsible for the larger primordial follicle pool in FST288-only females. Our results demonstrate that FST regulates the process of germ cell nest breakdown and germ cell apoptosis, accounting in part for the increased initial primordial follicle pool size in FST288-only females. The only known actions of FST involve antagonizing the actions of activins and related TGFβ superfamily members (8, 24–26), suggesting that reduced FST amount and/or altered FST isoform composition in these mice leads to increased activin bioavailability that causes a reduction in germ cell apoptosis and extends the germ cell nest breakdown in early neonatal ovarian development. This deduction is supported by the observation that activin administration to neonatal females on PND 0–4 resulted in increased primordial follicle pool size followed by more rapid demise of these follicles leading to a primordial follicle stock not different from untreated controls by puberty, suggesting the possibility that there is an optimal or maximal limit to primordial follicle number and that any excess is eliminated before adult reproduction commences (20). However, extending analysis of the primordial follicle pool size into adulthood in FST288-only females revealed that this accelerated demise of primordial follicles continued past puberty, leading to significantly fewer primordial follicles in adult females and premature cessation of ovarian activity (22). This suggests that the continued presence of excessive activin bioavailability in FST288-only females alters primordial follicle survival or activation in addition to regulating primordial follicle formation and germ cell nest breakdown.

Detailed follicle counting demonstrated that the process of germ cell nest breakdown was extended from the normal 5–6 d in WT mice to more than 8.5 d in FST288-only mice. The numbers of germ cells remaining in nests was significantly greater at all ages whether expressed in absolute terms or as a percent of total germ cells in the ovary. This suggests that increased activin bioavailability in FST288-only females retards a process known to involve gradual disruption of intercellular bridges between germ cells, germ cell apoptosis, invasion of somatic cells into the nests, and association of a few somatic cells with surviving germ cells to form primordial follicles (16). At present, the precise biochemical processes that are regulated by activin are unknown but we did observe reduced levels of germ cell apoptosis during nest breakdown in FST288-only females. Our results are therefore consistent with the proposal that germ cell nest breakdown is mechanistically linked to apoptosis (16).

Steroid hormones are also important for regulating germ cell nest breakdown because treatment of neonatal mice with natural or synthetic estrogens suppressed germ cell nest breakdown and primordial follicle formation in vivo (17). Genistein, a weak estrogen found in soy products, also affected oocyte survival (27). Furthermore estrogen, progesterone, and genistein were confirmed to retard germ cell nest breakdown and primordial follicle formation in vitro (17). Interestingly, estradiol suppressed activin β A subunit mRNA and protein in mouse ovaries (28), and activin regulates estrogen receptor expression (21) Moreover, notch signaling was recently demonstrated to induce the process of germ cell nest breakdown and primordial follicle formation (29), and this pathway has also been linked to TGFβ superfamily signaling (30), suggesting that the outcome of germ cell nest breakdown and primordial follicle formation is dependent on the relative signal strength of a complex of interacting pathways and that defects or perturbations in any of these can influence the outcome.

Prevailing evidence indicates that germ cell mitosis is completed by or just after birth in normal mice (16). Thus, one hypothesis for the increased number of primordial follicles observed in FST288-only females (this study) or in activin-treated neonates (20) is that this period of mitosis was extended resulting in more germ cells and thus more primordial follicles. Indeed, we did observe an increased number of germ cells in FST288-only mice, but this was apparent at birth so it must have resulted from the actions of activin or related TGFβ family member that is regulated by FST before birth. Detailed analysis of germ cell proliferation and apoptosis during embryonic development is required to decipher these processes.

Increased germ cell proliferation during nest breakdown was previously reported following neonatal activin treatment using proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) to identify proliferating germ cells (20). In contrast, we were unable to detect any proliferating germ cells in newborn WT or FST288-only ovaries using Ki67 as proliferation marker in combination with either Vasa or GCNA to identify germ cells and only two double-stained cells in FST288-only females (out of 8,000 germ cells counted) using BrdU as proliferation marker and Vasa to identify germ cells (none with GCNA as germ cell marker). Ki67 protein is present during all active phases of the cell cycle and would therefore be expected to include a wider range of germ cells than PCNA as PCNA is expressed in the nuclei of cells during only the DNA synthesis phase of the cell cycle (31). BrdU is incorporated in place of thymidine during DNA synthesis before mitosis so it not only marks cells that are proliferating but is also detectable in daughter cells, suggesting that an even wider range of proliferating cells should be detectable (32). Thus, we conclude that germ cell proliferation is extremely rare in FST288-only females after birth and does not account for the increased number of germ cells or primordial follicles.

The number of germ cells that ultimately survive as primordial follicles after germ cell nest breakdown depends on the number of germ cells before breakdown as well as the number that undergo apoptosis. While there are clearly more germ cells at birth in FST288-only females, it appears that reduced apoptosis also contributes to the increased primordial follicle pool. Results using different apoptosis markers, including the more traditional TUNEL as well as cleaved PARP1, a protein cleaved by caspase-3 early in the apoptosis program that has been used previously in oocytes (33), in combination with Vasa or GCNA as germ cell markers, were consistent and demonstrated significantly reduced apoptosis in FST288-only ovaries early in the breakdown process but significantly greater apoptosis up to PND 8.5, a time when apoptosis is undetectable in WT mice. Because the difference in germ cell number on PND 0.5 between FST288-only and WT ovaries is less than the difference in primordial follicle number at PND 8.5 (22) we conclude that reduced overall apoptosis during this extended germ cell nest breakdown period in FST288-only mice contributes to the enhanced primordial follicle stock. This is also indicated by the reduced rate of germ cell loss (20% vs. 40% for FST288 and WT ovaries respectively) observed in FST288-only ovaries when all germ cells were counted at PND 0.5–8.5. In contrast to our results, altered apoptosis was not observed when neonatal mice were treated with activin (20) perhaps suggesting that effects on apoptosis during germ cell nest breakdown depend on increased activin bioavailability before birth that occurs in FST288-only mice. Extending activin treatments to include the period before birth might address this question, although it may be difficult to get activin to cross the placenta. Nevertheless, we propose that decreased apoptosis combined with an enlarged initial germ cell number at birth is responsible for the enhanced primordial follicle stock in FST288-only females and that increased activin bioavailability is likely responsible for these alterations.

FST288-only mice were created by eliminating the alternative splice event that produces the mRNA encoding the FST315 protein which in gonads is processed to FST303. In vitro studies suggested that the different biochemical properties of the FST isoforms might lead to different functions in vivo (9). While global deletion of FST resulted in early neonatal death in mice (11), the FST288 isoform by itself is able to support development through adulthood, consistent with the hypotheses that the FST288 isoform is sufficient for development (9). Reproductive defects in FST288-only mice further suggest that the FST303 and/or FST315 isoforms may play critical roles in regulating germ cell proliferation, nest breakdown, and apoptosis that together account for an enlarged primordial follicle pool in neonates. Interestingly, we observed FST within nuclei of some but not all oocytes within nests and even in more mature follicles. The intensity of this staining was variable, especially within the nests. However, we were unable to consistently colocalize this FST with markers of apoptosis, nor were there differences between the genotypes in the number of germ cells containing FST positive nuclei. Thus, at this time it is unclear what physiological significance is conferred by this nuclear FST. However, nuclear FST in germ cells has been previously observed (34). Moreover, FST was recently localized to the nucleolus in HeLa cells where it reduced ribosomal RNA synthesis and promoted survival of these cells in low glucose environments (35). Thus, FST may have additional activities that influence oocyte apoptosis besides antagonism of secreted activin and related TGFβ family members.

Our results indicate that reduced FST amount and/or altered isoform composition leads to increased germ cell number at birth, extended germ cell nest breakdown, and reduced germ cell apoptosis, which together contribute to an enlarged primordial follicle pool. Taken together with our previous report detailing fertility defects in FST288-only mice that include reduced litter size, irregular cycles, resistance of secondary follicles to enter the antral follicle pool, and early cessation of ovarian activity, the results reported here suggest that these mice might be useful models for identifying potential mechanisms for the 70% of human POF cases for which no genetic abnormality has been identified. They also suggest a mechanism whereby environmental factors could influence the process of germ cell proliferation, nest breakdown, and/or primordial follicle formation that could account for some cases of POF in genetically predisposed women. While no polymorphisms in FST or the activin signaling system have yet been identified in POF patients, relatively few systematic studies have been performed so our results suggest that additional genetic analyses in POF patients may be warranted. Moreover, our results support the hypothesis that individual FST isoforms have specialized functions in mammals, some of which are critical for normal reproduction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Brooke Bentley for the expert technical assistance in tissue histology.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R21HD062859 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- BrdU

- Bromodeoxyuridine

- FST

- follistatin

- GCNA

- germ cell nuclear antigen

- NGS

- normal goat serum

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PND

- postnatal day

- POF

- premature ovarian failure

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Tortoriello DV, Sidis Y, Holtzman DA, Holmes WE, Schneyer AL. 2001. Human follistatin-related protein: a structural homologue of follistatin with nuclear localization. Endocrinology 142:3426–3434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ling N, Ying SY, Ueno N, Esch F, Denoroy L, Guillemin R. 1985. Isolation and partial characterization of a Mr 32,000 protein with inhibin activity from porcine follicular fluid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:7217–7221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sugino K, Kurosawa N, Nakamura T, Takio K, Shimasaki S, Ling N, Titani K, Sugino H. 1993. Molecular heterogeneity of follistatin, an activin-binding protein. Higher affinity of the carboxyl-terminal truncated forms for heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the ovarian granulosa cell. J Biol Chem 68:15579–15587 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vale W, Rivier C, Hsueh A, Campen C, Meunier H, Bicsak T, Vaughan J, Corrigan A, Bardin W, Sawchenko P, Spiess J, Rivier J. 1988. Chemical and biological characterization of the inhibin family of protein hormones. Rec Prog Horm Res 44:1–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mather JP, Moore A, Li RH. 1997. Activins, inhibins, and follistatins: further thoughts on a growing family of regulators. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 215:209–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xia Y, Schneyer AL. 2009. The biology of activin: recent advances in structure, regulation and function. J Endocr 202:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weiss J, Crowley WF, Jr, Halvorson LM, Jameson JL. 1993. Perifusion of rat pituitary cells with gonadotropin-releasing hormone, activin, and inhibin reveals distinct effects on gonadotropin gene expression and secretion. Endocrinology 132:2307–2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schneyer AL, Sidis Y, Gulati A, Sun JL, Keutmann H, Krasney PA. 2008. Differential antagonism of activin, myostatin and growth and differentiation factor 11 by wild-type and mutant follistatin. Endocrinology 149:4589–4595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sidis Y, Mukherjee A, Keutmann H, Delbaere A, Sadatsuki M, Schneyer A. 2006. Biological activity of follistatin isoforms and follistatin like-3 are dependent on differential cell surface binding and specificity for activin, myostatin and BMPs. Endocrinology 147:3586–3597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schneyer AL, Wang Q, Sidis Y, Sluss PM. 2004. Differential distribution of follistatin isoforms: application of a new FS315-specific immunoassay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:5067–5075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matzuk MM, Lu N, Vogel H, Sellheyer K, Roop DR, Bradley A. 1995. Multiple defects and perinatal death in mice deficient in follistatin. Nature 374:360–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jorgez CJ, Klysik M, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Matzuk MM. 2004. Granulosa cell-specific inactivation of follistatin causes female fertility defects. Mol Endocrinol 18:953–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Santoro N. 2003. Mechanisms of premature ovarian failure. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 64:87–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anasti JN. 1998. Premature ovarian failure: an update. Fertil Steril 70:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gosden RG, Faddy MJ. 1998. Biological bases of premature ovarian failure. Reprod Fertil Dev 10:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pepling ME. 2006. From primordial germ cell to primordial follicle: mammalian female germ cell development. Genesis 44:622–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen Y, Jefferson WN, Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Pepling ME. 2007. Estradiol, progesterone, and genistein inhibit oocyte nest breakdown and primordial follicle assembly in the neonatal mouse ovary in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology 148:3580–3590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Castrillon DH, Miao L, Kollipara R, Horner JW, DePinho RA. 2003. Suppression of ovarian follicle activation in mice by the transcription factor Foxo3a. Science 301:215–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. John GB, Gallardo TD, Shirley LJ, Castrillon DH. 2008. Foxo3 is a PI3K-dependent molecular switch controlling the initiation of oocyte growth. Dev Biol 321:197–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bristol-Gould SK, Kreeger PK, Selkirk CG, Kilen SM, Cook RW, Kipp JL, Shea LD, Mayo KE, Woodruff TK. 2006. Postnatal regulation of germ cells by activin: The establishment of the initial follicle pool. Dev Biol 298:132–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kipp JL, Kilen SM, Woodruff TK, Mayo KE. 2007. Activin regulates estrogen receptor gene expression in the mouse ovary. J Biol Chem 282:36755–36765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kimura F, Sidis Y, Bonomi L, Xia Y, Schneyer A. 2010. The follistatin-288 isoform alone is sufficient for survival but not for normal fertility in mice. Endocrinology 151:1310–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gobeil S, Boucher CC, Nadeau D, Poirier GG. 2001. Characterization of the necrotic cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1): implication of lysosomal proteases. Cell Death Differ 8:588–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sugino H, Sugino K, Hashimoto O, Shoji H, Nakamura T. 1997. Follistatin and its role as an activin-binding protein. J Med Invest 44:1–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Welt C, Sidis Y, Keutmann H, Schneyer A. 2002. Activins, inhibins, and follistatins: from endocrinology to signaling. A paradigm for the new millennium. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 227:724–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Otsuka F, Moore RK, Iemura S, Ueno N, Shimasaki S. 2001. Follistatin inhibits the function of the oocyte-derived factor BMP-15. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 289:961–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jefferson W, Newbold R, Padilla-Banks E, Pepling M. 2006. Neonatal genistein treatment alters ovarian differentiation in the mouse: inhibition of oocyte nest breakdown and increased oocyte survival. Biol Reprod 74:161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kipp JL, Kilen SM, Bristol-Gould S, Woodruff TK, Mayo KE. 2007. Neonatal exposure to estrogens suppresses activin expression and signaling in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology 148:1968–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trombly DJ, Woodruff TK, Mayo KE. 2009. Suppression of notch signaling in the neonatal mouse ovary decreases primordial follicle formation. Endocrinology 150:1014–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blokzijl A, Dahlqvist C, Reissmann E, Falk A, Moliner A, Lendahl U, Ibáñez CF. 2003. Cross-talk between the Notch and TGF-beta signaling pathways mediated by interaction of the Notch intracellular domain with Smad3. J Cell Biol 163:723–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scholzen T, Gerdes J. 2000. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol 182:311–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yu CC, Woods AL, Levison DA. 1992. The assessment of cellular proliferation by immunohistochemistry: a review of currently available methods and their applications. Histochem J 24:121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ghafari F, Gutierrez CG, Hartshorne GM. 2007. Apoptosis in mouse fetal and neonatal oocytes during meiotic prophase one. BMC Dev Biol 7:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kogawa K, Ogawa K, Hayashi Y, Nakamura T, Titani K, Sugino H. 1991. Immunohistochemical localization of follistatin in rat tissues. Endocrinol Jpn 38:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gao X, Wei S, Lai K, Sheng J, Su J, Zhu J, Dong H, Hu H, Xu Z. 2010. Nucleolar follistatin promotes cancer cell survival under glucose-deprived condition through inhibiting cellular rRNA synthesis. J Biol Chem 285:36857–36864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.