Abstract

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is centrally involved in growth, survival and metabolism. In cancer, mTOR is frequently hyperactivated and is a clinically validated target for therapy and drug development. Biologically, mTOR acts as the catalytic subunit of two functionally distinct complexes, called mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) which is predominantly cytoplasmic in subcellular localization and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) which is both cytoplasmic and nuclear. mTORC1 is sensitive to the selective inhibitor rapamycin. By contrast, mTORC2 is relatively resistant to rapamycin. Moreover, its putative downstream effector, Akt phosphorylated on serine 473 represents a signal transduction pathway for tumor survival. Phospholipase D (PLD) and its product, phosphatidic acid (PA) have been implicated as an activator of mTOR signaling, including the direct phosphorylative activation of p70S6K atthreonine 389. The latter promotes cell cycle progression. In this study, we investigated the activation status and subcellular localization of mTOR and the relative expression of PLD1, as well as their downstream effectors in a spectrum of uterine smooth muscle tumors using normal myometria as controls. The results show significant activation with overexpression of phosphorylated mTORC2 complex in uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS) and smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) as evidenced by nuclear localization of p-mTOR (Ser 2448) in ULMS>STUMP>uterine leiomyoma and normal myometria (p<0.05) and with overexpression of PLD1(p<0.05). Cor-relatively, there are overexpressions of nuclear p-Akt (Ser 473) and nuclear p-p70S6K (Thr 389) in ULMS and STUMP (p<0.05). The activation with overexpression of components of the mTORC2-PLD1 pathway in ULMS and to a lesser degree in STUMP provides insight into their tumorigenic mechanisms. Thus the development of therapies designed to target mTORC2 and PLD1 activity may be beneficial in treating ULMS.

Keywords: Morphoproteomics, mTORC2, phospholipase D1, uterine leiomyosarcoma, STUMP

Introduction

Uterine leiomyosarcomas (ULMSs) comprise 1% of the uterine malignancies and 45% of uterine sarcomas [1]. Patients usually present with abnormal uterine bleeding and often are para-menopausal with a median age at diagnosis of 50.9 years [2]. These tumors grow as solitary, bulky, flesh-like masses that invade the uterine wall or less often as polypoid lesions protruding into the endometrial cavity. The diagnosis frequently is made by the pathologist, after primary hysterectomy is performed by the gynecologic surgeon for presumed leiomyomas, unless metastatic disease is readily apparent. Cell cycle progression and specifically, a relatively high mitotic index is one of the criteria along with variable coagulative necrosis and/or moderate to severe atypia that is used to identify cases of ULMS and smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) [3]. In general, ULMSs are very aggressive tumors with a high recurrence rate ranging from 53% to 71% for those tumors confined to the uterus and the overall prognosis is grim with an overall 5-year survival ranging from 10-50% [4]. Surgery is the optimal treatment of ULMSs. The influence of adjuvant therapy on survival is uncertain and radiotherapy may only be useful in controlling local recurrences. Chemotherapy with doxorubicin or docetaxel/gemcitabine is now used for advanced or recurrent disease but with relatively low response rates (i.e., 27 to 36 %) [5, 6]. The molecular mechanisms underlying development of ULMSs are poorly understood. Wang, et al [7] reported on activating mutations in KIT oncogene in ULMSs. In a small portion of ULMSs, that are associated with the hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC), germline mutations and biallelic inactivation in fumarate hydratase (FH) gene at 1q43 were proposed to play a role in the pathogenesis of sporadic, early onset ULMSs [8,9]. More recently, studies have demonstrated that Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway may play a critical role in the development of leiomyosarcomas [10] and combining gemcitabine and rapamycin may be beneficial in treating human leiomyosarcoma patients [11].

To expand on this, the mTOR pathway plays a significant role in cell signaling pathways which promote tumorigenesis through coordinated phosphorylation of proteins that directly regulate protein synthesis, cell-cycle progression, cell growth and proliferation [12]. Studies have shown that activated mTOR leads to phosphorylative acitvation of p70S6kinase (p70S6K) at threonine 389, which contributes to increased G1 cell cycle progression and tumor cell proliferation [13-17]. Furthermore, dysregulation of PI3-K/Akt/mTOR signaling has been implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of many human cancers, such as cancers of head and neck [13], uterine cervix [17], prostate [18], liver [19], stomach [20], kidney [21], brain [22], urinary bladder [23], and breast [24]. The literature also contains reports with evidence of mTOR pathway activation in gynecological malignancies such as endometrial adenocarcinomas [25-27]. However, the literature on activation of the mTOR pathway in sarcoma, in general and in ULMS, in particular is limited [28-35].

At the cellular level, mTOR is found in two structurally and functionally distinct multiprotein complexes, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORcomplex 2 (mTORC2). Each has different components–most significantly raptor for mTORC1 and rictor for mTORC2 [36]. Rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor that prevents mTOR dependent downstream signal transduction. mTORC1 is rapamycin-sensitive while mTORC2 is relatively rapamycin-insensitive [36]. Additionally, Chen, et al. [12] demonstrated that mTORC2 is required for cell cycle progression through Akt dependent mechanisms. Importantly, Akt phosphorylated on serine 473 is regarded as a putative downstream effector of mTORC2 signaling [37]. Hence, it would be important to identify mTORC2 activation tumors as a target for molecular, signal transduction therapies. Finally, phospholipase D (PLD) and in particular, its metabolite, phosphatidic acid (PA) has recently been shown to be another mTOR facilitator and adjunct. Specifically, PA is required for the association of mTOR with raptor to form mTORC1 and that of mTOR with rictor to form mTORC2 [38]. Additionally, PA can directly phosphorylate p70S6K at threonine 389, independently of mTORC1 [39]. Suppressing PA production substantially increased the sensitivity of mTORC2 to rapamycin [38].

Because mTORC1 is predominantly cytoplasmic and mTORC2 is both nuclear and cytoplasmic [36], we proposed to use morphoproteomic analysis [40,41] to assess the relative subcellular distribution and expression levels of components of the mTOR-PLD signaling pathway and their downstream effectors in ULMS vis-a-vis uterine smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) and uterine leiomyoma and normal myometria. The intent was to provide insight into their respective biologies and expose new therapeutic opportunities for ULMS.

Materials and methods

Patient specimens

Following institutional review board (IRB) approval, paraffin-embedded tissue from 47 cases of smooth muscle tumors of the uterus were retrieved from the database of two institutions, Memorial Hermann Hospital at Texas Medical Center and Lyndon B Johnson General Hospital, Houston, TX.

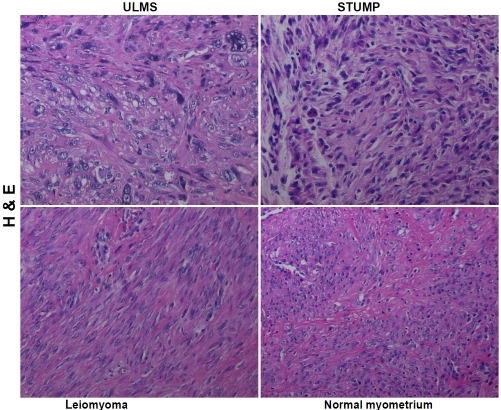

A tissue microarray was constructed using archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks from these 47 cases with an additional nine normal myometria serving as controls. This was accomplished using a tissue arrayer (Beecher Instruments, Sun Prairie, WI) that provides a 1-mm tissue core from each case. Hematoxylineosin (H&E) staining of the microarray sections confirmed histologically representative areas of the tumors or normal myometria and provided the following composition: 11 cases of uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS); 17 cases of uterine smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP);19 cases of non-gestational uterine leiomyomas and 9 normal myometria. Representative digital images from each of the subsets are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin-eosin (H & E) depictions of uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS), smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP), uterine leiomyoma and normal myometrium. Original magnification × 200.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue microarray (TMA) sections were cut at 4 um and were deparaffinized and rehydrated in a graded series of alcohols. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed.

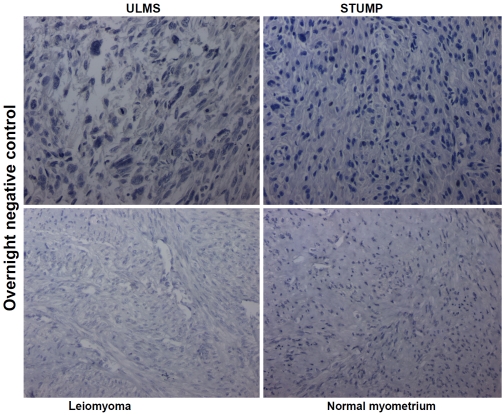

Immunohistochemistry was carried out using phosphospecific probes to include antibodies directed against three phosphorylated (p) antigens representing putative sites of activation: p-mTOR (Ser 2448); p-Akt (Ser 473) and p-p70S6K (Thr 389) [Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). In addition, an immunohistochemical probe was used to detect phospholipase D1 (PLD1) [Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA]. The sections were then treated with 3% H2O2 and rinsed with tris-buffered saline (TBS)/Tween-20. A few drops of diluted normal blocking serum were placed on the tissue and incubated at room temperature. The serum was then washed off and the sections were incubated with the primary antibodies (those incubated with one of the phosphospecific probes were incubated overnight at 4 degrees C per the vendors recommended procedure). The remainder of the staining procedure was carried out on a DAKO Autostainer programmed to incubate each slide with diluted biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 minutes. The slides were then rinsed and incubated with DAB (3, 3'-diamino-benzidine chromogen solution, DAKO Envision+ System Kit) for 10 minutes. The slides were rinsed again and counterstained with Gill II hematoxylin, treated with xylene and cover slipped. Positive and negative controls run concurrently were noted to react appropriately. Representative digital images of the overnight negative control at 4 degrees C from each of the subsets are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Digital images of the overnight negative control incubated at 4° C (minus the primary antibody) to serve as a frame of reference and comparison to the reactions observed in uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS), smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP), uterine leiomyoma and normal myometrium following exposure to the primary antibodies (see Figures 3-6). Original magnification × 200.

Immunohistochemical staining assessment and scoring

Semi-quantitative/qualitative assessment: The expression of p-mTOR (Ser 2448), p-Akt (Ser 473), p-p70S6K (Thr 389), and phospholipase D1 (PLD1) protein analytes were assessed using bright-field microscopy with regard to the following parameters: 1. Cellular compartmentalization of the chromogenic signal indicated as predominantly cytoplasmic or nuclear; 2. Percentage of positive cells from 1 to 100% was determined in the individual cases, and the positivity was further categorized as focal (<50% of cells positive) and diffuse (>50% of cells positive); and 3. Qualitative assessment of chromogenic signal intensity was graded as absent (0), mild (1+), moderate (2+), or strong (3+).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Pairwise Multiple Comparison Procedures using the Holmes-Sidak method.

Results

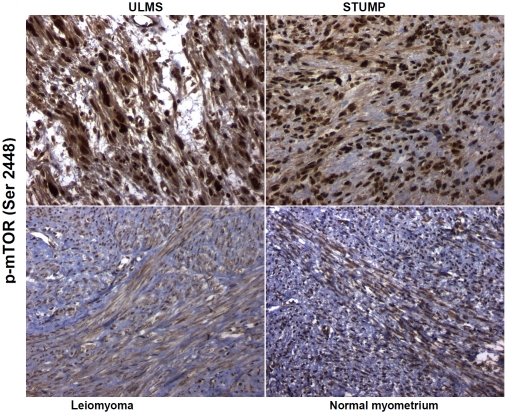

Subcellular compartmentalization and semi-quantitative / qualitative assessment of p-mTOR (Ser 2448) expression

The chromogenic signal for p-mTOR (Ser 2448) was primarily localized in the nuclei of cells in positive cases of ULMS, STUMP, uterine leiomyomas and normal myometria (controls). The immunoreactivity for p-mTOR (Ser 2448) in ULMSs was diffuse (>50% of tumor cells positive) in 10 of 11 (91%) cases with moderate to strong (2+ to 3+) intensity of nuclear expression. One case of ULMS showed mild (1+) but diffuse nuclear immunoexpression. Ten of seventeen (59%) of STUMPs exhibited moderate to strong (2+ to 3+) and diffuse nuclear expression (>50% of tumor cells positive) whereas 7 (41%) showed mild (1+ to <2+) albeit diffuse nuclear expression. One of nineteen cases (∼5%) of non-gestational leiomyomata demonstrated moderate (2+) and diffuse nuclear immunoreactivity, while the remaining eighteen (∼95%) had diffuse, mild (1+) nuclear reactivity for this analyte. All nine cases of normal myometria showed only mild (0 to 1+) and diffuse nuclear immunoreactivity for p-mTOR (Ser 2448). These observations are depicted in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Expression of p-mTOR (Ser 2448) in uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS), smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP), uterine leiomyoma and normal myometrium. Phosphospecific antibodies against p-mTOR at serine 2448 show brown chromogenic signals primarily in the nuclear compartments in all subsets but with appreciably stronger intensity in ULMS and STUMP. Original magnification × 200.

Table 1.

Overexpression of component proteins of Akt-mTOR-p70S6K pathway and Phospholipase D1 in uterine smooth muscle tumors

| p-Akt * (% cases) | p-mTOR * (% cases) | p-p70S6K* (% cases) | Phospholipase D1* (% cases) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leiomyosarcoma | 91 | 91 | 91 | 73 |

| STUMP | 65 | 59 | 71 | 24 |

| Leiomyoma | 17 | 5 | 31 | 0 |

| Normal myometria | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

Moderate to strong (2+ to 3+) expression (also see Figure 7)

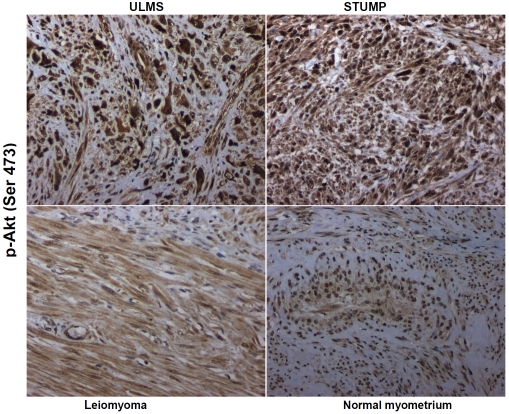

Subcellular compartmentalization and semi-quantitative/qualitative assessment of p-Akt (Ser 473) expression

The localization of p-Akt (Ser 473) was primarily nuclear in the subsets of cases in this study. Moderate to strong (2+ to 3+) and diffuse (>50% of tumor cells positive) was observed in 10 of 11 (91%) of ULMS and 11 of the 17 (65%) of STUMPS. One case of ULMS showed mild (1+) immunoexpression. Six cases of STUMPs (35%) exhibited mild (1+ to <2+) albeit diffuse immunoreactivity. Seventeen non-gestational leiomyomas were available to assess the expression of p-Akt (Ser 473) and three (17%) of these showed moderate (2+) diffuse primarily nuclear expression while the remaining 14 cases (83%) had mild (1+ to <2+) and diffuse nuclear expression of this analyte. Once again, all nine cases of normal myometria exhibited mild nuclear (1+) and diffuse immunoreactivity for p-Akt (Ser 473). These data are depicted in Figure 4 and summarized in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Expression of downstream effector of mTORC2 signaling, namely p-Akt at serine 473. Phosphspecific antibody against p-Akt (Ser 473) shows nuclear and cytoplasmic expression in all subsets but with greater signal intensity in the nuclei of uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS) and smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP). Original maginification × 200.

Subcellular compartmentalization and semi-quantitative/qualitative assessment of phospholipase D1 (PLD1) expression

The cellular immunolocalization of phospholipase D1 (PLD1) was cytoplasmic when positive (nucleoli are generally positive in all cells and serve as an internal control). Ten of the eleven (91%) ULMS showed cytoplasmic PLD1 expression. Of these, eight cases exhibited moderate (2+) and diffuse (>50% of tumor cells positive) while 2 cases had mild (1+) expression. Nine of seventeen (53%) STUMPs showed cytoplasmic PLD1 expression. Of these nine, 4 had moderate (2+) expression and five were mildly (1+) and diffusely positive. No such PLD1 expression was observed in uterine leiomyomas or normal myometria (0 to ± cytoplasmic expression).These are illustrated in Figure 5 and summarized in Table 1.

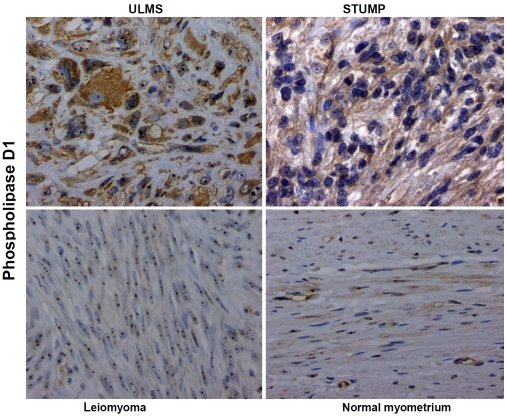

Figure 5.

Isoform specific antibody against phospholipase D1 (PLD1) shows chromogenic signals in both cytoplasmic and nucleolar compartments in the uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS) and to a lesser degree, in the smooth muscle tumor of uncertain potential (STUMP) subsets and contrastively weak to no cytoplasmic signal in the uterine leiomyoma and normal myometrium subsets. Original magnification × 400.

Subcellular compartmentalization and semi-quantitative/qualitative assessment of p-p70S6K (Thr 389)

Localization of p70S6K phosphorylated on threonine 389 in nuclei was evident in positive cases. Moderate to strong (2+ to 3+) and diffuse (>50% of tumor cells positive) nuclear staining of p-p70S6K (Thr 389) was observed in 10 out of 11 (91%) ULMSs. Only one case of ULMS showed no immunoexpression of p-p70S6K (Thr 389). Twelve of the 17 (71%) STUMPs were moderately to strongly positive (2+ to 3+) and diffusely immunoreactive. The remaining five cases (29%) of STUMP exhibited mild (1+ to <2+) diffuse immunoreactivity. Six of 19 (31%) non-gestational leiomyomas showed moderate (2+) and diffuse nuclear expression. The remaining 13 cases (69%) had mild (1+) diffuse immunoreactivity. Two of the nine (22%) of normal myometria (controls) showed moderate (2+) and diffuse nuclear positivity. The remaining cases (78%) of normal myometria displayed mild (1+) and diffuse nuclear expression of p-p70S6K (Thr 389). Digital images representative of these reactions are contained in Figure 6 and Table 1.

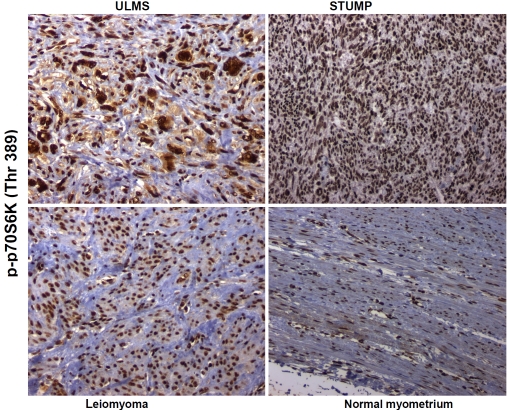

Figure 6.

The phosphospecific antibody against p70S6K phosphorylated on threonine 389 shows strong nuclear signal for this analyte in uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS) and smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) with lesser signal intensities in leiomyoma and normal myometrium. Original magnification × 200.

Statistical analyses of data sets

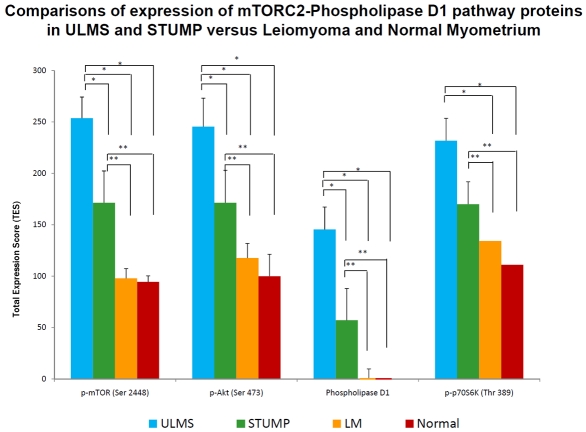

In addition to the semi-quantitative / qualitative levels of expression, a total expression score (TES) was generated for each of the protein analytes in the study group (i.e., p-mTOR [Ser 2448], p-Akt [Ser 473], phospholipase D1, and p-p70S6K [Thr 389]). The TES score is the product of the percent of tumor cells positive x the intensity score. Subsequently, these data for each subset in the study were statistically analyzed using ANOVA and All Pairwise Multiple Comparison Procedures by the Holmes-Sidak method. The results of these statistical analyses affirm significant activation with overexpression of phosphorylated mTORC2 complex in ULMS and STUMP as evidenced by nuclear localization of p-mTOR (Ser 2448) in ULMS>STUMP>uterine leiomyoma and normal myometria and of PLD1 (p<0.05). Correlatively, there are also statistically significant overex-pressions of nuclear p-Akt (Ser 473) and nuclear p-p70S6K (Thr 389) in ULMS and STUMP. These data are graphically depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparisons of expression of mTORC2-phospholipase D1 pathway proteins in ULMS and STUMP versus leiomyoma and normal myometrium. * p< 0.05 compared with ULMS (uterine leiomyosarcoma) groups and ** p< 0.05 compared with STUMP (smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential) groups using ANOVA and Holm-Sidak method for pairwise multiple comparison.

Discussion

Morphoproteomics [40, 41] utilizes morphology and proteomics in an attempt to define the biology of tumors. The latter incorporates phos-phospecific, immunohistochemical probes directed against putative sites of activation of signal transduction molecules and assesses the correlative expression of effectors of an activated pathway and of protein analytes associated with its enhancement. Morphology, in this context, provides for the assessment of both subcellular compartmentalization of such protein analytes (i.e., plasmalemmal, cytoplasmic and/or nuclear), thereby permitting further sub-categorization of the signal transduction pathways and of the overexpression of a given protein analyte in the tumor cells vis-`a-vis its non-neoplastic or benign counterpart. In this study regarding the mTOR signaling pathway in a spectrum of uterine smooth muscle tumors, morphoproteomic analysis demonstrates: 1. constitutive activation of the mTORC2 pathway in ULMS and STUMP, as evidenced by nuclear localization with statistically significant overexpression of both p-mTOR (Ser 2448) and its downstream effector, p-Akt (Ser 473); and 2. overexpression of the companionate PLD-PA pathway in ULMS and STUMP, as indicated by the overexpression of PLD1 and one of its downstream effectors, p-p70S6K (Thr 389).

A computer-assisted search of the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE database provides supportive evidence for our morphoproteomic findings and conclusions. mTOR has been found to be localized both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Rosnerand Hengstschlager [36] characterized the nuclear /cytoplasmic distribution of mTOR complex components in non-transformed, non-immortalized human diploid fibroblasts. They reported that raptor has a very low affinity for mTOR in the nucleus and hence very low amounts of mTOR-raptor (mTORC1) are detected in the nucleus. In contrast, mTOR-rictor (mTORC2) is present and detected abundantly both in cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments. Parenthetically, the activated form of mTOR, phosphoryated at serine 2448 binds to both raptor and rictor [42]. In short, these findings strongly suggest that the expression of p-mTOR (Ser 2448) in the nucleus reflects the presence of p-mTOR (Ser 2448)-rictor or mTORC2 complex and is consistent with our conclusion of constitutive activation with overexpression of the nuclear mTORC2 pathway in ULMS and STUMP. This is further strengthened by the concomitant morphoproteomic finding of constitutively activated and overexpressed p-Akt (Ser 473) in the nuclei of ULMS and STUMP, given the role for mTORC2 and specifically, rictor in the activation of Akt resulting in its phosphorylation on serine 473 [37, 42-46]. Another concomitant, namely the overexpression of cytoplasmic phospholipase D1 in ULMS and STUMP provides another correlate for mTORC2 overexpression, given the fact that phosphatidic acid, a product of PLD1 is required for the assembly and stabilization of mTORC2 complexes and perhaps its activation [38, 47]. Moreover, Lehman and colleagues [39] reported that phosphatidic acid, the product of phospholipase D activity can directly phosphorylate p70S6K on threonine 389 and thereby, account for activation of S6 ribosomal protein in the absence of mTORC1 signaling.

Correlatively, ULMS and to a lesser extent, STUMP show cell cycle progression into the mitotic phase [3]. (The average mitotic index in our series and subsets of cases are in accord with this general tenet at: 18 mitotic figures/10 high power fields in ULMS>2.8 in STUMP>0.9 in uterine leiomyoma>0.0 in normal myometria). Because p70S6K function is reportedly essential for G1 progression into the S phase [13-17, 48], its constitutive activation and overexpression coincides with such cell cycle progression in ULMS and STUMP. Not surprisingly, inhibition of the canonical mTORC1/p70S6K pathway by rapamycin effects a G1 cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells [49].

Lastly, when one considers our findings of a constitutively activated and overexpressed mTORC2-phospholipase D1 pathway in ULMS and STUMP in the context of what is already known at the genomic and proteomic level concerning potential upstream signal transducers in leiomyosarcoma; it is clear that the insulin-like growth factor pathway plays both a major role in the pathogenesis of such aberrant signaling and correspondingly raises new therapeutic options. Specifically, it is reported that mTORC2 can be activated by insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 and phosphorylatesSer 473 in the hydrophobic motif of Akt[50]. In leiomyosarcoma, including those originating in the uterus, there are multiple reports of increased IGF-II peptide and/or mRNA, and IGF-II signaling has been implicated in tumor growth progression [51-54]. Moreover, it has been noted that autocrine IGF-II in leiomyosarcoma cells induces cell invasion and protection from apoptosis via the insulin receptor isoform A [54]. Additional connections between IGF signaling in leiomyosarcoma and mTORC2 are suggested by the depiction in other studies of insulin receptor isoform A utilizing insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1/2 [55] and the recent finding of a nuclear complex of rictor and insulin receptor sub-strate-2 [56]. Against this background and in the context of our morphoproteomic findings, we propose that metformin may be a therapeutic option in the treatment of ULMS, based on preclinical data, for the following reasons: 1. metformin is an AMP dependent kinase (AMPK) agonist and as such promotes phosphorylative inactivation of IRS-1 at serine 789 while down-regulating Akt phosphorylation at serine 473, mTOR phosphorylated at serine 2448 and IRS-1 levels [57]; 2. metformin reduces the levels of lysophosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylcholine, the substrates for phospholipase D [58] and 3. metformin, independent of the AMPK pathway, directly inhibits the activity of p70S6K1 while reducing the level of p70S6K, phosphorylated on threonine 389 [59].

In summary, morphoproteomic analysis reveals the overexpression of nuclear p-mTOR (Ser 2448), nuclear p-Akt (Ser 473) and phospholipase D1 in ULMS>STUMP>uterine leiomyoma and normal myometria. Additionally, this coincides with the increased expression of p-p70S6K (Thr 389) and is consistent with the generally accepted cell cycle progression into the mitotic phase in ULMS and STUMP, in supporting a role for the mTORC2-phospholipase D1 pathway in the pathogenesis of STUMP and ULMS and suggests a new therapeutic strategy to target this pathway and halt the progression of ULMS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Richard A. Breckenridge (ASCP) and Pamela K. Johnston (ASCP) for their technical assistance and Bheravi Patel for secretarial and graphic support.

References

- 1.Solomon LA, Schimp VL, Ali-Fehmi R, Diamond MP, Munkarah AR. Clinical update of smooth muscle tumors of the uterus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dafopoulos A, Tsikouras P, Dimitraki M, Galazios G, Liberis V, Maroulis G, Teichmann AT. The role of lymphadenectomy in uterine leiomyosarcoma: review of the literature and recommendations for the standard surgical procedure. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;282:293–300. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1524-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.9th edition. Philadelphia, USA: Mosby, An affiliate of Elsevier Inc; 2004. Female reproductive system; p. 1612. ROSAI AND ACKERMAN's Surgical Pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Angelo E, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hensley ML, Blessing JA, Mannel R, Rose PG. Fixed-dose rate gemcitabine plus docetaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group phase II trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hensley ML, Ishill N, Soslow R, Larkin J, Abu-Rustum N, Sabbatini P, Konner J, Tew W, Spriggs D, Aghajanian CA. Adjuvant gemcitabine plus docetaxel for completely resected stages I-IV high grade uterine leiomyosarcoma: results of a prospective study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009;112:563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Felix JC, Lee JL, Tan PY, Tourgeman DE, O'Meara AT, Amezcua CA. The proto-oncogene c-kit is expressed in leiomyosarcomas of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:402–406. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ylisaukkooja SK, Kiuru M, Lehtonen HJ, Lehtonen R, Pukkala E, Arola J, Launonen V, Aaltonen LA, Kiuru M, Lehtonen HJ, et al. Analysis of fumarate hydratase mutations in a population-based series of early onset uterine leiomyosarcoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:283–287. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehtonen HJ, Kiuru M, Ylisaukko-Oja SK, Salovaara R, Herva R, Koivisto PA, Vierimaa O, Aittomäki K, Pukkala E, Launonen V, Aaltonen LA. Increased risk of cancer in patients with fu-marate hydratase germline mutation. J Med Genet. 2006;43:523–526. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernando E, Charytonowicz E, Dudas ME, Menendez S, Matushansky I, Mills J, Socci ND, Behrendt N, Ma L, Maki RG, Pandolfi PP, Cordon-Cardo C. The AKT-mTOR pathway plays a critical role in the development of leiomyosarcomas. Nat Med. 2007;13:748–753. doi: 10.1038/nm1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merimsky O, Gorzalczany Y, Sagi-Eisenberg R. Molecular impacts of rapamycin-based drug combinations: combining rapamycin with gemcitabine or imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) in a human leiomyosarcoma model. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen XG, Liu F, Song XF, Wang ZH, Dong ZQ, Hu ZQ, Lan RZ, Guan W, Zhou TG, Xu XM, Lei H, Ye ZQ, Peng EJ, Du LH, Zhuang QY. Rapamycin regulates Akt and ERK phosphorylation through mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling pathways. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:603–610. doi: 10.1002/mc.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown RE, Zhang PL, Lun M, Zhu S, Pellitteri PK, Riefkohl W, Law A, Wood GC, Kennedy TL. Morphoproteomic and pharmacoproteomic rationale for mTOR effectors as therapeutic targets in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2006;36:273–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown RE, Tan D, Taylor JS, Miller M, Prichard JW, Kott MM. Morphoproteomic confirmation of constitutively activated mTOR, ERK, and NF-kappaB pathways in high risk neuro-blastoma, with cell cycle and protein analyte correlates. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2007;37:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao N, Zhang Z, Jiang BH, Shi X. Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in the cell cycle progression of human prostate cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:1124–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao N, Flynn DC, Zhang Z, Zhong XS, Walker V, Liu KJ, Shi X, Jiang BH. G1 cell cycle progression and the expression of G1 cyclins are regulated by PI3K/AKT/mTOR/p70S6K1 signaling in human ovarian cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C281–291. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00422.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng W, Duan X, Liu J, Xiao J, Brown RE. Morphoproteomic evidence of constitutively activated and overexpressed mTOR pathway in cervical squamous carcinoma and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2:249–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown RE, Zotalis G, Zhang PL, Zhao B. Morpho-proteomic confirmation of a constitutively activated mTOR pathway in high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1:333–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Tan D, Zhang Z, Liang JJ, Brown RE. Activation of Akt-mTOR-p70S6K pathway in angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:713–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng W, Brown RE, Trung CD, Li W, Wang L, Khoury T, Alrawi S, Yao J, Xia K, Tan D. Morpho-proteomic profile of mTOR, Ras/Raf kinase/ERK, and NF-kappaB pathways in human gastric ade-nocarcinoma. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;38:195–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin F, Zhang PL, Yang XJ, Prichard JW, Lun M, Brown RE. Morphoproteomic and molecular concomitants of an overexpressed and activated mTOR pathway in renal cell carcinomas. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2006;36:283–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu X, Pandolfi PP, Li Y, Koutcher JA, Rosenblum M, Holland EC. mTOR promotes survival and astrocytic characteristics induced by Pten/AKT signaling in glioblastoma. Neoplasia. 2005;7:356–368. doi: 10.1593/neo.04595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margaret A Knowles, Fiona M Platt, Rebecca L Ross, Carolyn D. Hurst. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway activation in bladder cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:305–316. doi: 10.1007/s10555-009-9198-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghayad SE, Cohen PA. Inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. A new hope for breast cancer patients. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2010;5:29–57. doi: 10.2174/157489210789702208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.No JH, Jeon YT, Park IA, Kang D, Kim JW, Park NH, Kang SB, Song YS. Expression of mTOR protein and its clinical significance in endometrial cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darb-Esfahani S, Faggad A, Noske A, Weichert W, Buckendahl AC, Müller B, Budczies J, Röske A, Dietel M, Denkert C. Phospho-mTOR and phospho-4EBP1 in endometrial adenocarci-noma: association with stage and grade in vivo and link with response to rapamycin treatment in vitro. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:933–941. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0529-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi Shen, Melissa L Stanton, Wei Feng, Rodriguez ME, Ramondetta L, Chen L, Brown RE, Duan X. Morphoproteomic analysis reveals an overexpressed and constitutively activated phospholi-pase D1-mTORC2 pathway in endometrial carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4:13–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wing LY, Chen HM, Chuang PC, Wu MH, Tsai SJ. The mammalian target of rapamycin-p70 ribo-somal S6 kinase but not phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt signaling is responsible for fibroblast growth factor-9-induced cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19937–19947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wan X, Helman LJ. The biology behind mTOR inhibition in sarcoma. Oncologist. 2007;12:1007–1018. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-8-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown RE. Morphoproteomic portrait of the mTOR pathway in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2004;34:397–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwenofu OH, Lackman RD, Staddon AP, Goodwin DG, Haupt HM, Brooks JS. Phospho-S6 ribosomal protea potential new predictive sarcoma marker for targeted mTOR therapy. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:231–237. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernando E, Charytonowicz E, Dudas ME, Menendez S, Matushansky I, Mills J, Socci ND, Behrendt N, Ma L, Maki RG, Pandolfi PP, Cordon-Cardo C. The AKT-mTOR pathway plays a critical role in the development of leiomyosarcomas. Nat Med. 2007;13:748–753. doi: 10.1038/nm1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crabtree JS, Jelinsky SA, Harris HA, Choe SE, Cotreau MM, Kimberland ML, Wilson E, Saraf KA, Liu W, McCampbell AS, Dave B, Broaddus RR, Brown EL, Kao W, Skotnicki JS, Abou-Gharbia M, Winneker RC, Walker CL. Comparison of human and rat uterine leiomyomata: identification of a dysregulated mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6171–6178. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin XJ, Wang G, Khan-Dawood FS. Requirements of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin for estrogen-induced proliferation in uterine leiomyoma- and myometrium-derived cell lines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(176):e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaffer S, Shynlova O, Lye S. Mammalian target of rapamycin is activated in association with myo-metrial proliferation during pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4672–4680. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosner M, Hengstschläger M. Cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution of the protein complexes mTORC1 and mTORC2: rapamycin triggers dephosphorylation and delocalization of the mTORC2 components rictor and sin1. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2934–2948. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhaskar PT, Hay N. The two TORCs and Akt. Dev Cell. 2007;12:487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toschi A, Lee E, Xu L, Garcia A, Gadir N, Foster DA. Regulation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 complex assembly by phosphatidic acid: competition with rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1411–1420. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00782-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehman N, Ledford B, Di Fulvio M, Frondorf K, McPhail LC, Gomez-Cambronero J. Phospholipase D2-derived phosphatidic acid binds to and activates ribosomal p70 S6 kinase independently of mTOR. FASEB J. 2007;21:1075–1087. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6652com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown RE. Morphoproteomics: exposing protein circuitaries in tumors to identify potential therapeutic targets in cancer patients. Exp Rev Proteomics. 2005;2:337–348. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown RE. Morphogenomics and morphoproteomics: a role for anatomic pathology in personalized medicine. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:568–579. doi: 10.5858/133.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosner M, Siegel N, Valli A, Fuchs C, Hengstschläger M. mTOR phosphorylated at S2448 binds to raptor and rictor. Amino Acids. 2010;38:223–228. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hresko RC, Mueckler M. mTOR.RICTOR is the Ser473 kinase for Akt/protein kinase B in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40406–40416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breuleux M, Klopfenstein M, Stephan C, Doughty CA, Barys L, Maira SM, Kwiatkowski D, Lane HA. Increased AKT S473 phosphorylation after mTORC1 inhibition is rictor dependent and does not predict tumor cell response to PI3K/mTOR inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:742–753. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada O, Ozaki K, Nakatake M, Kakiuchi Y, Akiyama M, Mitsuishi T, Kawauchi K, Matsuoka R. Akt and PKC are involved not only in upregulation of telomerase activity but also in cell differentiation-related function via mTORC2 in leukemia cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2010;134:555–563. doi: 10.1007/s00418-010-0764-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fayard E, Xue G, Parcellier A, Bozulic L, Hemmings BA. Protein Kinase B (PKB/Akt), a Key Mediator of the PI3K Signaling Pathway. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;346:31–56. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang Y, Vilella-Bach M, Bachmann R, Flanigan A, Chen J. Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science. 2001;294:1942–1945. doi: 10.1126/science.1066015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lane HA, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ, Thomas G. p70s6k function is essential for G1 progression. Nature. 1993;363:170–172. doi: 10.1038/363170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carraway H, Hidalgo M. New targets for therapy in breast cancer: mammalian target of rapamy-cin (mTOR) antagonists. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:219–224. doi: 10.1186/bcr927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cybulski N, Polak P, Auwerx J, Rüegg MA, Hall MN. mTOR complex 2 in adipose tissue negatively controls whole-body growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9902–9907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811321106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daughaday WH, Emanuele MA, Brooks MH, Barbato AL, Kapadia M, Rotwein P. Synthesis and secretion of insulin-like growth factor II by a leio-myosarcoma with associated hypoglycemia. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1434–1440. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812013192202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gloudemans T, Prinsen I, Van Unnik JA, Lips CJ, Den Otter W, Sussenbach JS. Insulin-like growth factor gene expression in human smooth muscle tumors. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6689–6695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van der Ven LT, Roholl PJ, Gloudemans T, Van Buul-Offers SC, Welters MJ, Bladergroen BA, Faber JA, Sussenbach JS, Den Otter W. Expression of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), their receptors and IGF binding protein-3 in normal, benign and malignant smooth muscle tissues. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1631–1640. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sciacca L, Mineo R, Pandini G, Murabito A, Vigneri R, Belfiore A. In IGF-I receptor-deficient leiomyosarcoma cells autocrine IGF-II induces cell invasion and protection from apoptosis via the insulin receptor isoform A. Oncogene. 2002;21:8240–8250. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leibiger B, Leibiger IB, Moede T, Kemper S, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR, de Vargas LM, Berggren PO. Selective insulin signaling through A and B insulin receptors regulates transcription of insulin and glucokinase genes in pancreatic beta cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:559–570. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh BK, Singh A, Mascarenhas DD. A nuclear complex of rictor and insulin receptor substrate-2 is associated with albuminuria in diabetic mice. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:355–363. doi: 10.1089/met.2010.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zakikhani M, Blouin MJ, Piura E, Pollak MN. Metformin and rapamycin have distinct effects on the AKT pathway and proliferation in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:271–279. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0763-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wanninger J, Neumeier M, et al. Metformin reduces cellular lysophosphatidylcholine and thereby may lower apolipoprotein B secretion in primary human hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;178:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vaszuez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez JA. The antidiabetic drug metformin suppresses HER2 (erbB-2) oncoprotein overexpression via inhibition of the mTOR effector p70S6K1 in human breast carcinoma cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:88–96. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.1.7499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]