Abstract

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a rare and distinct variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with characteristic morphologic, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic features. We report a case of ALK-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a 44-year-old male with progressively worsening unilateral nasal congestion and obstruction secondary to a nasopharyngeal mass. Radiologically, the mass was showed to extend to orophanrynx from nasopharynx. Histologically, the tumor cells exhibited plasmablastic morphology with expression of Bob-1, CD4, CD10, CD45, CD56, CD138, EMA, MUM1, Oct-2, and kappa immunoglobulin light chain, but negative for CD20, CD30, CD79a, PAX-5, and lambda. More importantly, the neoplastic cells showed positive immunoreactivity for ALK with exclusive cytoplasmic granular staining pattern. This case represented the second reported ALK-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the nasopharyngeal region.

Keywords: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, nasopharyngeal mass, CD4, CD10

Introduction

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a rare and distinct subtype of DLBCL, accounting for less than 1% of DLBCL. Since its first report by Delsol et al. [1] in 1997, there have been approximately 50 reported cases. ALK-positive DLBCL occurs more frequently in male adults with a male to female ratio of 3:1 and spans all age groups (9-70) with a median of 36 years [2]. While ALK-positive DLBCL primarily involves lymph nodes, extranodal presentations such as the tongue, nasopharynx, and stomach have been rarely reported [3-6]. Histologically, the lymphoma cells of ALK-positive DLBCL show plasmablastic and/or immunoblastic morphology with a sinusoidal growth pattern, and a unique immunophenotypic profile characterized by a lack of CD20 and CD30, and granular cytoplasmic ALK reactivity in the majority of the reported cases [2]. However, cases of ALK-positive DLBCL with strong CD20 expression have been occasionally encountered [7]. Molecular cytogenetics and/or reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction have shown that the most commonly observed cytogenetic abnormality of ALK-positive DLBCL is t (2;17)(p23;q23) involving Clathrin (CLTC) on 17q23 and ALK on 2p23 [4,8]. However, cases of ALK-positive DLBCL with underlying t(2;5) (p23;q35) involving ALK on 2p23 and nucleo-phosmin on 5q35, as seen in the majority of T/ null anaplastic large cell lymphoma, did exist [3]. Here we report a second case of primary extranodal ALK-positive DLBCL presenting as a nasopharyngeal mass.

Case report

Clinical history

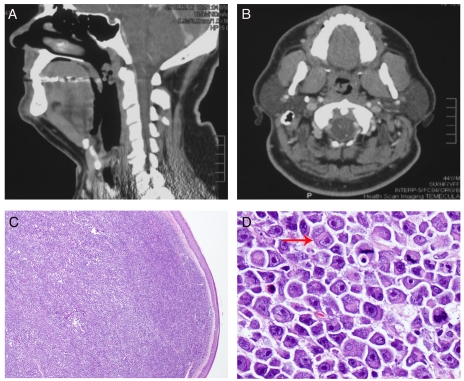

The patient is a 44-year-old male referred from an outside hospital with a right-sided nasopharyngeal mass. He reported progressively worsening right-sided nasal congestion, snoring, and difficulty sleeping for months. He denied any nasal bleeding or any other sinonasal symptoms. Computer tomography showed a pedun-culated nasopharyngeal mass extending into the oropharyngeal region with no evidence of bony erosion (Figure 1A and B). Endoscopically, the tumor was a mucosal-covered flesh-colored mass with 2.5 cm in greatest diameter. The mass was attached to the posterolateral nasopharynx near the torus with near-total ball-valve obstruction of the nasopharynx. The mass was surgically resected with no complications. Fresh tissue was not procured for conventional cytoge-netic analysis. The patient had a history of woodworking, social alcohol and tobacco use, and hypertension. His HIV status is unknown. The patient was to start chemotherapy at the time of this report.

Figure 1.

Radiologic and morphologic features of the nasopharyngeal mass. A. Lateral review of the CT scan of head and neck demonstrated a posterior-lateral pedunculated nasopharyngeal mass measuring 3×2 cm; B. Anterior posterior review of the CT scan at the level of the nasopharynx showed a pedunculated mass attached to the right lateral/posterior nasopharyngeal wall; C. A diffuse dense sub-mucosal lymphoid infiltrate was seen at low magnification (H&E, original magnification 20×); D. At higher magnification, the atypical lymphoid cells showed oval to irregular nuclear contours, eccentrically located nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant cytoplasm with frequent peri-nuclear hofs. Brisk of mitotic rate was easily appreciated (H&E, original magnification 400×).

Histology

The surgically removed specimen was formalin fixed and paraffin embedded. H&E sections were made according to standard methods.

Immunohistochemistry and In situ hybridization

The immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization were performed using the Dako Autostainer with Envision(+) Detection Kit (Dako, Dakocy-tomation, Carointeria, CA) at the Department of Pathology of University of California San Diego. The detailed information regarding antibodies used in the study was summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dilution and sources of antibodies used in immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

| Antigen | Dilution | Vendor | Antigen | Dilution | Vendor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALK | 1:40 | Dako, Carpinteria, CA | CD138 | 1:60 | abD Serotec, Taleigh, NC |

| BCL-6 | 1:10 | Biocare Medical, Concord, CA | EBV | 1:300 | Dako |

| Bob-1 | 1:60 | Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA | EMA | 1:2 | Dako |

| CD2 | 1:20 | Novocastra | HMB-45 | 1:2 | Dako |

| CD3 | 1:50 | Lab Vision, Fremont, CA | Kappa (IHC) | 1:500 | Biocare Medical |

| CD4 | 1:20 | Biocare Medical | Kappa (ISH) | N/A | ZytoVision, Germany |

| CD5 | 1:50 | Biocare Medical | Lambda (IHC) | 1:35 | Biocare Medical |

| CD7 | 1:40 | Biocare Medical | Lambda (ISH) | N/A | ZytoVision |

| CD8 | 1:80 | Biocare Medical | LANA | 1:25 | UCSD, San Diego, CA |

| CD10 | 1:40 | Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA | Lysozyme | 1:150 | Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA |

| CD19 | 1:400 | Biocare Medical | Mart-1 | 1:100 | Dako |

| CD20 | 1:250 | Dako | MIB-1 | 1:50 | Dako |

| CD30 | 1:20 | Dako | MPO | 1:10,000 | Dako |

| CD34 | 1:30 | Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA | MUM1 | 1:50 | Dako |

| CD43 | 1:60 | Dako | Oct-2 | 1:50 | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA |

| CD45 | 1:100 | Dako | Pan-cytokeratin | Cocktail | Dako |

| CD45RA | 1:40 | Dako | PAX-5 | 1:40 | Biocare Medical |

| CD56 | 1:10 | Biocare Medical | S100 | 1:20 | Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA |

| CD68 | 1:15 | Dako | TdT | 1:25 | Dako |

| CD79a | 1:50 | Dako | TIA-1 | 1:100 | Biocare Medical |

ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase; N: negative; P: positive; EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; EMA: epithelial membrane antigen; IHC: immunohistochemistry; ISH: in situ hybridization; LANA: human herpes virus -8 (HHV-8) latency associated nuclear antigen; Pan-cytokeratin cocktail: AE1/AE3(1:30) plus MNF116 (1:30); TdT: terminal deoxynucleotidyl trans-ferase; TIA-1: T-cell intracellular antigen 1.

Results

Morphologic features

At the lower magnification, there was a diffuse infiltrate beneath the oral non-keratinized squamous mucosa (Figure 1C). At high magnification, there were sheets of monomorphic medium-sized to large atypical lymphoid cells with oval to irregular nuclear contours, prominent nucleoli, and abundant cytoplasm (Figure 1D). Some of the atypical lymphoid cells showed eccentrically located nuclei with peri-nuclear hof, reminiscent of plasmablasts (Figure 1D). While the vast majority of the atypical lymphoid cells were mononucleated, occasional bi-nucleated cells were present (arrow in Figure 1D). In addition, frequent mitoses were easily appreciated.

Immunophenotypic characteristics

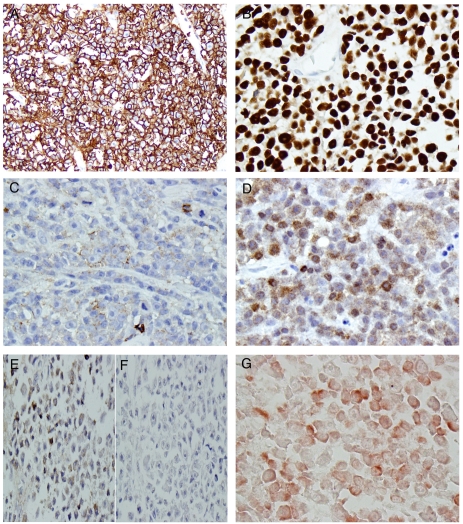

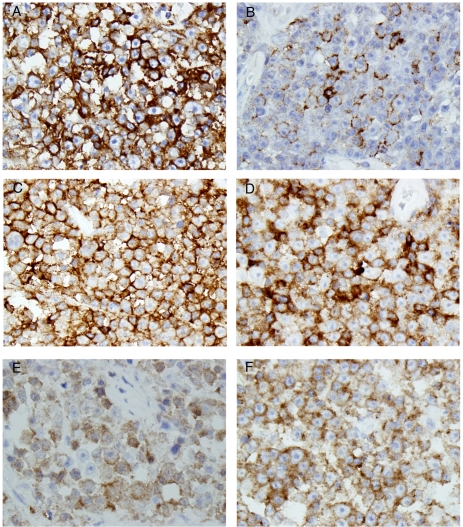

In order to determine the nature of this lymphoid infiltrate, a panel of immunohistochemistry was performed, and the results were summarized in Table 2. The atypical lymphoid cells were strongly and diffusely positive for CD45 (Figure 2A) and Oct-2 (Figure 2B), weakly and partially positive for CD19 (Figure 2C), and partially positive for Bob-1 (Figure 2D). While these atypical lymphoid cells showed weak positive kappa (Figure 2E) but negative lambda (Figure 2F) immunoglobulin light chain expression as revealed by immunohistochemistry, the in situ hybridization clearly demonstrated kappa restriction among the atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 2G). Other B-cell antigens tested (CD20 and CD79a, data not shown) were negative. Consistent with the plasmablastic morphology, these neoplastic cells were strongly and diffusely positive for CD138 (Figure 3A) and partially positive for EMA (Figure 3B). Furthermore, these cells were positive for CD4 (Figure 3C), CD10 (Figure 3D), and partially and weakly positive for CD56 (Figure 3E). Finally, these cells showed positive ALK immunoreactivity with restricted cytoplasmic granular staining pattern (Figure 3F).

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical profile

| Antigen | Result | Antigen | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALK | P (cytoplasmic granule) | CD138 | P |

| BCL-6 | N | EBV | N |

| Bob-1 | P (partial) | EMA | P |

| CD2 | N | HMB-45 | N |

| CD3 | N | Kappa (IHC) | P (weak) |

| CD4 | P | Kappa (ISH) | P |

| CD5 | N | Lambda (IHC) | N |

| CD7 | N | Lambda (ISH) | N |

| CD8 | N | LANA | N |

| CD10 | P | Lysozyme | N |

| CD19 | P (weak and partial) | Mart-1 | N |

| CD20 | N | MIB-1 | P (50%) |

| CD30 | N | MPO | N |

| CD34 | N | MUM1 | P |

| CD43 | N | Oct-2 | P |

| CD45 | P | Pan-cytokeratin | N |

| CD45RA | N | PAX-5 | N |

| CD56 | P | S100 | N |

| CD68 | N | TdT | N |

| CD79a | N | TIA-1 | N |

ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase; N: negative; P: positive; EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; EMA: epithelial membrane antigen; IHC: immunohistochemistry; ISH: in situ hybridization; LANA: human herpes virus -8 (HHV-8) latency associated nuclear antigen; TdT: terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase; TIA-1: T-cell intracellular antigen 1.

Figure 2.

The neoplastic cells exhibited B-cell lineage immunophenotype. The tumor cells were strongly and diffusely positive for CD45 (A), Oct-2 (B), weakly and partially positive for CD19 (C), and Bob-1 (D). The tumor cells were weakly positive for kappa (E), but negative for lambda (F). In situ hybridization revealed the tumor cells were positive for kappa immunoglobulin light chain (G) (Original magnification for A, B, C, D, E, F, and G were 200×, 400×, 400×, 400×, 400×, 400×, and 400×, respectively).

Figure 3.

Additional immunohistochemical profile of the tumor cells. The tumor cells were strongly and diffusely positive for CD138 (A), partially positive for EMA (B), strongly and diffusely positive for CD10 (C), CD4 (D), weakly and partially positive for CD56 (E). These tumor cells showed restricted cytoplasmic granular positivity for ALK (F) (Original magnification for A, B, C, D, E, and F were 400×, 400×, 400×, 400×, 400×, and 400×, respectively).

Discussion

Based on the morphological features and immunohistochemical profile, we report a case of nasopharyngeal ALK-positive DLBCL. This case represented the second reported ALK-positive DLBCL in the region of nasopharynx [5]. Like the previous case [5], the current case also showed restricted cytoplasmic granular staining pattern for ALK, therefore, the underlying genetic abnormality is most likely a balanced translocation between chromosomes 2 and 17 involving CLTC and ALK, although fluorescence in situ hybridization and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction are needed for definitive demonstration of such t(2;17) translocation.

While most of the reported ALK-positive DLBCLs were lymph node based, extra-nodal presentation rarely occurred, and ear, nose and throat were seldom encountered. For example, among 33 cases reviewed by Reichard et al (5), 10% (3/33) were found in the otolaryngeal region. Similarly, among 38 cases reviewed by Laurent et al (6), 7.9% (3/38) developed as a nasal tumor. In addition, Beltran et al also reported a case of ALK-DLBCL in the nasal fossa [7]. Although our patient had a history of woodworking, such a detailed description among other reported 6 cases [5,6] in this region was not known, therefore, the cause-effect relationship between woodworking and development of ALK-positive DLBCL in the otolarygeal region is not known.

By gene expression profiling, DLBCL was divided into germinal center B (GCB)-cell-like and non-GCB-like groups [8], and the immunohisto-chemical application of this molecular sub-classification of DLBCL was made possible by Han et al by using a limited number of antigens [9]. Our case was classified as GCB-like im-munophenotype based on the positive CD10 expression, and this is the first case of ALK-positive DLBCL in which CD10 was positive. Accumulated evidence has demonstrated favorable response to CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) therapy in DLBCL with GCB-like immunophenotype (10), although DLBCL with GCB-like immunophenotype also showed a significantly better 3-year overall survival in rituximab (R) plus CHOP regimen (R-CHOP) in some studies [10], while others demonstrated BCL-6, but not CD10, bore significant prognostic value in R-CHOP era [11]. However, due to lack of such clinical study in ALK-positive DLBCL, the significance of effect of GCB immunophenotype on prognosis remains to be investigated, and more cases are needed. Another factor needing to be considered is whether to include rituximab in ALK-positive DLBCL in that only 3-8% of ALK-positive DLBCL expressed CD20 [5, 6].

Since ALK-positive DLBCL is such a rare entity, clinical trial to find an optimal treatment regimen has not been reported to date, and the treatment regimen used was either empirical or anecdotal. For example, in reviewing 38 cases of ALK-positive DLBCL treated with either CHOP-derivative regimen, CHOP, or R-CHOP plus or minus radiation therapy, Laurent et al [6] showed the overall clinical course was poor with a median survival of 12.2 months. Compared to stages 1 & 2, patients of ALK-positive DLBCL with stages 3 & 4 showed a significantly shorter overall survival [6].

In summary, we report a second case of naso-pharyngeal ALK-positive DLBCL, and the first ALK-positive DLBCL with documented GCB-like immunophenotype based on the expression of CD10. While definitive molecular cytogenetics or molecular studies were not performed, based on the exclusive cytoplasmic granular staining pattern of ALK, a t(2;17) involving ALK on 2p23 and CLTC on 17q23 is the most likely underlying cytogenetic aberrancy. ALK-positive DLBCL appears to be a distinct disease entity with an aggressive process that carries a poor prognosis. Although the medial survival is only 12.2 months (6), longer survival (more than 10 years) has been reported in isolated cases with localized disease [3, 6]. The current standard of treatment appears to be insufficient; therefore, novel therapeutic modalities are needed to combat this aggressive clinicopathological entity.

References

- 1.Delsol G, Campo E, Gascoyne RD. ALK-positive large B-cell lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001. pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delsol G, Lamant L, Mariame B, et al. A new subtype of large B-cell lymphoma expressing the ALK kinase and lacking the 2; 5 translocation. Blood. 1997;89:1483–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onciu M, Behm FG, Downing JR, et al. ALK positive plasmablastic B-cell lymphoma with expression of the NPM-ALK fusion transcript: Report of 2 cases. Blood. 2003;102:2642–2644. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chikatsu N, Kojima H, Suzukawa K, et al. ALK+, CD30-, CD20- large B-cell lymphoma containing anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fused to clathrin heavy chain gene (CLTC) Mod Pathol. 2003;16:828–832. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000081729.40230.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichard KK, McKenna RW, Kroft SH. ALK-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: report of four cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:310–319. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurent C, Do C, Gascoyne RD, Lamant L, Ysebaert L, Laurent G, Delsol G, Brousset P. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase -positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A rare clinicopathologic entity with poor prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4211–4216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltran B, Castillo J, Salas R, Quinones P, Morales D, Hurtado F, et al. ALK-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, Boldrick JC, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275–282. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seki R, Ohshima K, Fujisaki T, Uike N, Kawano F, Gondo H, et al. Prognostic impact of immunohistochemical biomarkers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1842–1847. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ke F, Weisenburger DD, Choi WW, Perry KD, Smith LM, Shi X, et al. Addition of rituximab to standard chemotherapy improves the survival of both the germinal center B-cell-like and non-germinal center B-cell-like subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4587–4594. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]