ABSTRACT

Palliative care is an approach to care that seeks to improve the quality of life of patients and families facing problems due to life-threatening malignancies. Interventional radiology offers diagnostic, therapeutic, and palliative procedures that provide tangible benefits to oncology patients. A comprehensive evaluation and goals of care discussion will facilitate appropriate treatment recommendations from interventionalists. We describe a framework, with suggested questions for patients, which will enhance the level of communication between interventionalists and oncology patients.

Keywords: Palliative care, decision making, ethics, goals of care, interventional radiology

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary medical specialty based on a philosophy of care focused on both the patients and their families.1 There is commonly confusion about the difference between hospice care and palliative care. To explain the difference, it helps to recall high school geometry: A rhombus is a square, but a square is not a rhombus. Metaphorically, hospice is a rhombus and palliative care is a square: Specifically, hospice is an example of palliative care for patients at the end of life, but palliative care, although sharing many principles, is much broader than hospice. Palliative care affirms life and strives to improve the quality of life of patients regardless of life expectancy. Hospice, in contrast, is palliative care for those at the end of life; it regards dying as a normal part of the life cycle and strives to integrate the physical, psychological, and spiritual domains of patient care to provide total care. Interventions used in palliative care target any manifestations of suffering in any domain in an attempt to help patients remain as active and engaged as possible irrespective of prognosis. Given the broad scope of palliative care, providers commonly work in interdisciplinary teams including physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and other health-care professionals.

Interventional radiology (IR) is a growing, dynamic specialty in which providers are trained to perform a myriad of therapies, procedures, and other interventions to assist in the diagnosis and management of cancer patients. Interventional radiologists often perform procedures meant to relieve suffering and are a component of interdisciplinary palliative care.

This article explores and discusses the intersection of palliative care and IR, which creates a platform to discuss a method for resolving decisions about what can be done for a patient versus what should be done to relieve pain and suffering. We briefly summarize the history of palliative care, provide an overview of the comprehensive palliative care patient evaluation and a framework for a goals of care discussion, and review the ethics of patient autonomy in the informed consent process.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF PALLIATIVE CARE

Dame Cicely Saunders, an English physician and clinical scientist, is credited with starting the modern hospice movement when she founded St. Christopher's Hospice in London in 1967. Dr. Balfour Mount, a Canadian surgical oncologist, briefly trained at St. Christopher's and coined the term palliative care in 1974, from the Latin root palliare (“to cloak”). He used the term to describe an inpatient palliative care unit he created to care for the dying within the Royal Victoria Hospital. Dr. T. Declan Walsh developed the first academic palliative care service in the United States as part of a comprehensive cancer center in 1987 at the Cleveland Clinic.2 In 2006, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) established a new subspecialty certificate in palliative medicine and, owing to the interdisciplinary nature of palliative care, marked the first time 10 ABMS member boards had collaborated in the creation of a new certification.3 The first certification exam will be administered in 2008.

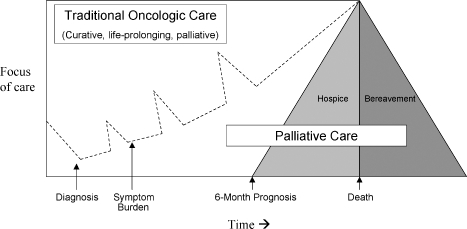

Even with the emergence of palliative medicine as a subspecialty, there is often confusion about the distinction between palliative care and hospice. Palliative care emerged from the hospice movement to address a more general need for pain and symptom management in patients with serious disease who were not at the end of life. Palliative care coexists with life-prolonging therapy such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy to relieve suffering from disease and its treatment concurrently throughout the illness trajectory. Hospice is charged with caring for patients in the last 6 months of life and focuses primarily on the relief of suffering while neither hastening nor prolonging an individual's death (Fig. 1). Hospice and palliative care have similar aims for patient care, and palliative care practitioners frequently work together to help transition patients near the end of life to hospice.

Figure 1.

A model for the integration of palliative care and traditional oncology care. (Adapted from Emanuel LL, Ferris FD, von Gunten CF, Von Roenn JH. EPEC-O: Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care—Oncology. Chicago: The EPEC Project; 2005.)

Palliative care, then, is best administered throughout the continuum of illness to relieve suffering.4 Palliative interventions include the full range of potential therapies: medical, surgical, interventional procedures, radiation, and chemotherapy. Palliative care views the patient and family as the unit of care who participate together to develop a comprehensive plan for care. In addition to the traditional medical models of care, palliative interventions also include a comprehensive patient and family evaluation, ideally from an interdisciplinary team, to gain a complete understanding of the patient and family unit. This evaluation includes understanding the story of a patient's life and his or her spiritual and religious background, sources of strength, or other unique attributes. This evaluation builds a relationship and establishes the trust that recommendations will be consistent with the patient and family's value system. Once a team has developed a relationship, come to understand a patient's goals, and framed that in the context of the ongoing medical issue, the team can educate more effectively and counsel patients about treatment options that best fit those goals. The team attempts to cultivate a mindset of living with illness—not letting the illness define their life—to remind patients that the self is primary and illness secondary. Palliative practitioners attempt to define clearly the impact of interventions on survival and symptom control so the patient/family unit can reach an informed, goals-consistent decision about preferred interventions.

INTERVENTIONAL RADIOLOGY AND ONCOLOGICAL PALLIATIVE CARE

IR is an important component of life-prolonging as well as symptom-relieving therapy for cancer patients, from diagnosis through the terminal phase of a cancer illness. Interventionalists provide crucial assistance in the decision-making process, especially regarding the potential risks and benefits of a given procedure. Traditional IR, with its roots in diagnostic radiology, has a technical mindset, and yet there is a growing debate within the field encouraging an enhanced clinical relationship between the interventionalist and the patient.5 The clinical/adviser role is essential in the management of complicated cancer patients where the risk-benefit ratio of a particular procedure may be uncertain and the advice of the interventionalist is invaluable to both the primary oncologist and patient. Charles Dotter, a major figure in the development of the IR field, noted in 1980. “The angiographer who enters into the treatment of arterial obstructive disease can now play a key role, if he is prepared and willing to serve as a true clinician, not just a skilled catheter mechanic.”6 As IR physicians have developed their clinical skills and become more involved in the pre- and postprocedure care of patients and assist patients in the decision-making process, they have an increased responsibility to act in the patient's best interest, even if this means disagreeing with the primary oncologist. Interventionalists, then, need the skills to establish goals of care with patients if they are to provide optimal recommendations for the individual and the highest standard of care.

Oncologist and palliative care practitioners base rational treatment decisions on the patient and family's defined goals of care. As such, palliative care physicians may be just as apt to recommend an invasive procedure as prescribe additional medication, depending on a particular patient's performance status and goals. Vertebroplasty for a compression fracture, surgical resection of a brain metastasis, surgical pinning of a pathological fracture, invasive management of persistent effusions, and radiofrequency ablation of painful lesions are just some examples of aggressive procedures that provide appropriate palliation.

COMPREHENSIVE PALLIATIVE CARE EVALUATION

Palliative care physicians evaluate patients and their families to identify the causes of suffering. Palliative care providers' training in navigating difficult topics and conversations makes these practitioners a valuable asset to the care of oncology patients. A palliative care comprehensive medical evaluation includes the standard history and physical examination as well as additional questions to investigate other potential causes of suffering. The underlying goals of the comprehensive evaluation are to build a relationship with the patient and family, facilitate a genuine understanding of the patient's perspective on illness and suffering, identify suffering and its cause, and define personal and medical goals for the future. The model relies on the assumption that a health care professional is better able to make a personalized recommendation if the other person is truly understood.

Palliative care physicians and researchers have developed several comprehensive assessment tools to help evaluate patients' preferences, symptoms, and causes of suffering.7,8,9 In general, comprehensive assessment tools, such as the PEACE tool9 assess various domains: Physical symptoms, Emotional and cognitive symptoms, Autonomy-related issues, Communication and closure of life issues, and Existential issues. Table 1 lists sample questions for each of the domains.

Table 1.

PEACE tool, Example of the Domains, and Sample Questions in a Comprehensive Palliative Care Assessment Tool

| PEACE Tool | ||

|---|---|---|

| Domain | Symptom | Question |

| Physical | Pain | Are you in pain? |

| Anorexia | How is your appetite? | |

| Genitourinary | Do you have control of your bladder? | |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea? Vomiting? Diarrhea? Constipation? | |

| Respiratory | Are you short of breath? Do you have a cough? | |

| Skin | Any irritation, rash, bruises, ulcers, or infection? | |

| Level of function | How many naps do you take each day? | |

| Are you able to prepare your own meals? | ||

| How far can you walk without taking a break? | ||

| Treatment side effects | Are you having side effects from you medicine? | |

| Emotional | Sad | Are you sad? |

| Anxiety | Are you anxious? | |

| Depression | Are you depressed? | |

| Autonomy | Control | Do you feel in control of your care? |

| Are we doing only the things you want? | ||

| Do you know what to expect? | ||

| Decision making | Do you feel you are heard/listened to? | |

| Are your preferences being followed? | ||

| Have you named an alternate decision maker? | ||

| Do you have a health-care power of attorney? | ||

| Communication and closure | Closure, life review, hopes | What do you hope for? |

| What are your dreams and goals? | ||

| What are things /projects you still want to achieve/complete? | ||

| What do you still enjoy doing? | ||

| Are there any people you have not seen in a long time you wish to contact/talk to? | ||

| Legacy | How would you like to be remembered? | |

| What are you especially proud of? | ||

| Support, relationships | Who are you closest to? | |

| What brings you joy? | ||

| Resilience and self-efficacy | What gives you strength? | |

| What do you do to help yourself? | ||

| Economic | Are you worried about money? | |

| Has your illness created a financial strain? | ||

| Do you worry you may become a burden to your family? | ||

| Transcendent and existential | Are you at peace? | |

| Are you suffering? | ||

| Do you think about dying? | ||

| Is faith important to you? | ||

Patients interpret their symptom burden in the context of their understanding of their illness. For example, a cancer patient may not complain about pain because he assumes pain is an expected part of his illness. In another case, a patient may not complain because she perceives cancer as the result of a personal failure (often spiritual) and believes pain is the price she must pay for the infraction. Alternatively, a patient may be satisfied with a pain score of 5 out of 10 because it is tolerable and balances most effectively side effects and function. “Best care” requires understanding of both the patient's perception of their illness and treatment and their goals.

Physicians and patients both approach medical decision making in a complex and nuanced manner. For many people, the process takes place at a subconscious level: The patient trusts that the physician has considered the various options and is recommending the best available therapeutic choice. This places the burden on the physician to make a recommendation congruent with the patient's goals. The comprehensive palliative evaluation is one method of gaining the necessary insight to support these decisions.

ETHICS

In the United States, competent patients have autonomy: the right to use their judgment to make decisions regarding their own medical care. Further, there are negative rights of autonomy and positive rights of autonomy. Negative rights are absolute: A patient with capacity has the right to refuse any intervention or therapy. Positive rights of autonomy, the right that a person be provided with something, are more limited and include, for example, the right of all elderly persons in the United States to have Medicare pay for their health care.10 The following example details positive and negative rights of autonomy.

A 53-year-old patient with hypertensive nephropathy on dialysis is recommended to have a kidney transplant by his nephrologist. The patient can refuse transplantation and continue with dialysis if he understands the implications of his choice and prefers not to undergo surgery and immunosuppressive medication therapy. Further, because dialysis is an intervention, the patient could elect to stop dialysis even if it meant a certain death as long as he is determined to have the capacity to make medical decisions. These are all examples of a patient exercising his negative right of autonomy. But a dialysis patient cannot approach his or her physician and demand a kidney transplant and have it performed without an appropriate indication. A patient's right of positive autonomy is thus limited.

Physicians have considerable influence on a patient's decision making during the informed consent process. The major barriers to autonomous consent include low socioeconomic status, poor education, old age, lengthy hospital stay, stress, language barriers, and misinterpretation of probabilistic data.11 Patients may defer to the physician's recommendations, especially in high-risk populations. Because patients often depend on the physician to make the “best” recommendation, it is incumbent on the physician to make therapy decisions based on a clear understanding of the patient's clinical situation and goals of care.

As physicians review the possible therapeutic options, one framework to begin evaluating the choices for a particular patient is to consider interventions categorically as diagnostic, curative, life prolonging, or purely palliative (i.e., symptom relief is the expected outcome). For example, one may be willing to accept significantly more toxicity for a potentially curative procedure than for one that is primarily palliative. The anticipated risks and potential benefits must be clearly presented and the patient informed that the intent of an intervention may not translate into outcome. For example, a procedure done to prolong life (e.g., radioactive TheraSpheres for hepatocellular carcinoma) may potentially lengthen life, affect no change, or even shorten life due to procedural morbidity.

Interventional radiology is instrumental in the management of many cancer patients throughout the disease course, from diagnosis to the treatment of the cancer and its symptoms. Diagnostic procedures in oncological patients, such as biopsies, are often performed by IR. It should be recognized that, although biopsies are necessary, they may contribute to both psychological and physical suffering12 and counseling is important even at this early stage. Life-prolonging interventions include antitumor treatments such as TheraSpheres, chemoembolization, or radiofrequency ablation; endovascular devices; management of loculated infection; and the placement of indwelling drains for chronic effusion management. Kyphoplasty and radiofrequency ablation of bone lesions are examples of purely palliative interventions.

GOALS OF CARE

Multiple investigators have shown that a patient's preference for a treatment is more likely to be influence by the overall outcome for a particular procedure than the direct risks and benefits of the intervention itself.13,14 In particular, patients consider the overall burden of the treatment (including the estimated length of time in the hospital, how invasive the procedure is, and the need for additional testing before or after the procedure), the perceived benefit of the ideal outcome, and the likelihood of the ideal outcome when making decisions.14 Patients may consider some conditions, such as severe dementia, coma, or a persistent vegetative state, as worse than death.13 Advance directives and living wills, although one example of goal setting, typically focus on a patient's preference regarding specific treatments in a narrow range of specific circumstances and are seldom helpful outside of those clinical scenarios. They provide a patient the opportunity to opt out or refuse certain treatments in certain situations if they are unable to speak for themselves. The desirability of an intervention depends heavily on its outcome. To better understand this concept, consider the different likely outcomes for a given procedure: intubation in a patient with pneumonia versus a patient with respiratory failure secondary to cachexia from advanced cancer. The patient with pneumonia may reasonably expect to be extubated and return to his premorbid quality of life versus the cancer patient who is unlikely to survive extubation. If the consent discussion was limited to the benefits and risks of the intubation itself—“inserting a tube and allowing a machine to breathe for you”—many patients would likely consent. Discussion of the goals of care and the goals of the intervention help focus patients and physicians on the most realistic outcome from a procedure and limit the use of procedures with low potential to achieve the desired result.

Although a goals of care discussion script does not exist, there are several important topics to address with patients. Table 2 suggests some sample questions to assist in defining goals of care. The questions included in the table may be useful for the interventionalist trying to gather information before making a recommendation about potential procedures. Identify the patient's anticipated outcome and address expectations in the preprocedure discussion. This is of particular importance if the patient's expectations are unlikely to be met by the specific intervention. Some studies have indicated that “what seriously ill patients really want from medical care is relief of suffering, help in minimizing the burden on families, closer relationships with family members, and a sense of control.”15 When considering the options, and prior to meeting with the patient and family, the physician may choose to consider the following: How can I help reduce the patient's suffering? How can I maximize their sense of control? How will this procedure impact the family (in terms of increased burden of care, financial strain, emotional stress)? Am I acting in the best interest of the patient? And ultimately, am I helping?

Table 2.

Framework for a Goals of Care Discussion

| Assess present understanding: |

| “Tell me what you understand about your illness.” |

| “What do you know about your cancer?” |

| “What have your doctors told you about your health?” |

| Develop an understanding of the patient's priorities: |

| “What is most important to you?” |

| “It's important to me to honor your wishes. To make the best recommendations, I need to understand your priorities better.” |

| “Are there things or projects you want to finish?” |

| “What is it that you really want from me/the health-care system/your doctors?” |

| “What could I do that would help you the most?” |

| Understand other influences on decision making |

| “Is your faith important to you?” |

| “Tell me about how your life philosophy guides how you make decisions.” |

| Assess your own perceptions and priorities of the patient's situation by asking yourself these questions: |

| How can I help reduce my patient's suffering? |

| How can I maximize his or her sense of control? |

| How will this procedure impact on the family (consider increased burden of care, financial strain, emotional stress)? |

| Am I acting in the best interest of my patient? |

| Am I helping?15 |

This thought exercise helps the physician explore the risks and benefits of a procedure from a patient-centered perspective and provides an outcome-focused recommendation for the patient. In learning about the patient's values, goals for life and health care, and his or her expectations for outcomes of the procedure, the physician may discover the answer to the initial question: Am I offering this procedure because I can or because I should?

To highlight some of the issues discussed in the body of the text, consider the following case examples.

Emily

Chief Complaint: Emily is a 48-year-old white woman with metastatic lung cancer (pleural and bone sites of involvement) who now presents to the office complaining of worsening shortness of breath. She is found to have a large left-sided pleural effusion.

History of Present Illness: Emily presented with metastatic disease and achieved a partial response with a planned six cycles of chemotherapy, including resolution of her pleural effusion. She has had stable disease for 4 months off therapy. She tolerated chemotherapy well and has remained active, working part time and taking care of her two teenager living at home. Her appetite is good and she has gained back the weight she lost prior to diagnosis.

Ethan

Chief Complaint: Ethan is a 48-year-old white man with metastatic lung cancer who also presents with worsening shortness of breath and is found to have a new large pleural effusion.

History of Present Illness: Ethan's lung cancer was metastatic at the time of diagnosis (lung, liver, and bone involvement), and he has been on chemotherapy for the past 9 months. His disease progressed through first- and second-line chemotherapy, and he was subsequently started on an oral, selective epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor 4 weeks ago. Ethan's activity has been decreasing steadily due to fatigue and shortness of breath. He now spends most of his day either in bed or in his recliner by the television. He is losing weight, and his present weight is 80% of his premorbid weight. Ethan's teenage children have been helping him with activities of daily living for 3 weeks.

Discussion

The management of a new pleural effusion, from a medical perspective, is relatively straightforward and logical: thoracentesis with fluid analysis to establish a diagnosis (i.e., malignant versus infectious or other cause) followed by appropriate management. If the effusion was determined to be malignant, therapeutic options would include fluid drainage by serial thoracentesis or a semipermanent drainage catheter, antitumor therapy, pleurodesis, or medical management only. To determine the most appropriate course of action, consider the medical options in the context of the patient's goals of care.

Case

In both of our cases, a bedside diagnostic and therapeutic thoracentesis revealed an exudative effusion with cytology positive for adenocarcinoma. Further imaging by computed tomography scan demonstrated progression of the underlying malignancy.

Emily has now progressed on first-line chemotherapy but still has multiple potentially effective chemotherapy options for her underlying malignancy. Her primary goal is to live as long as possible and see her oldest son graduate from high school at the end of the year. She understands she has an incurable cancer and has been preparing with her family and loved ones for her eventual death. She has prepared her advance directive and financial documents and is actively involved in life-closure activities: spending time with loved ones, light travel, finishing a writing project she started in college.

Ethan's cancer has progressed without any prior response to antitumor therapy. His performance status has declined precipitously. His primary life goal is to live as long as possible and see his oldest son graduate from high school at the end of the year. He also understands he has an incurable cancer and has spent time preparing his family for his death but has not felt well enough in the past few months to make any concrete plans. He would like to finish his advance directives and his will, but he has been too weak. With further questioning, he acknowledges that it is most important to him that he maximize his time at home with his wife and children.

Discussion

Both Emily and Ethan are faced with a similar physiological problem: dyspnea caused by a pleural effusion and underlying lung cancer. They have similar primarily life goals: to live as long as possible.

Emily's clinical situation favors additional systemic antitumor therapy, but she needs immediate palliation of her acute shortness of breath and would benefit from a therapeutic thoracentesis. She would then be a candidate for second-line chemotherapy that ideally would improve or stabilize her malignancy.

Ethan's poor performance status and progressive disease suggest that further antitumor therapy might cause more harm than benefit. His shortness of breath may improve with a therapeutic thoracentesis. Depending on the degree and duration of symptomatic benefit from the thoracentesis, he may be a candidate for a tunneled drainage catheter. A discussion about transitioning to palliative care or hospice to provide additional expertise in the management of physical and psychological symptoms would be of benefit and help him address his life goals, completing important documents and maximizing his time at home with this family.

Conclusion

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary medical specialty based on an approach to patient care focused on relieving suffering in any dimension: physical, psychological, existential, or spiritual. IR is an important adjunct for palliation of physical symptoms in patients with cancer. The decision-making process to determine which interventions are appropriate for a particular patient relies heavily on a goals of care discussion based on the particulars of a patient's own life and medical goals in the context of the stage of disease and prognosis. Patients are more concerned with procedural outcomes and the impact on their life rather than procedural details. Asking patients about their expectations for a procedure and then focusing the preprocedure consent discussion on the anticipated most likely outcomes of the intervention is most helpful for decision making. And finally, before recommending a procedure, consider its likelihood of relieving suffering, maximizing a patient's sense of control, minimizing negative impact on the family, and genuinely helping patients achieve their goals.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization WHO definition of palliative care. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en. Accessed December 8, 2006. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en

- Walsh T D. Continuing care in a medical center: the Cleveland Clinic Foundation Palliative Care Service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1990;5:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(90)90043-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available at http://www.abms.org/Downloads/News/NewsubcertinPalliativeMedicine101006FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2006. http://www.abms.org/Downloads/News/NewsubcertinPalliativeMedicine101006FINAL.pdf

- Meyers F J, Linder J. Simultaneous care: disease treatment and palliative care throughout illness. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1412–1415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy T P. Clinical interventional radiology: serving the patient. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:401–403. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000064850.87207.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G J. The 1999 Charles T. Dotter Lecture. Interventional radiology 2000 and beyond; back from the brink. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:681–687. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(99)70102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel L L, Alpert H R, Emanuel E E. Concise screening questions for clinical assessments of terminal care: the needs near the end-of-life care screening tool. J Palliat Med. 2001;4:465–474. doi: 10.1089/109662101753381601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser K E, Bosworth H B, Clipp E C, et al. Initial assessment of a new instrument to measure quality of life at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:829–841. doi: 10.1089/10966210260499014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okon T R, Evans J M, Gomez C F, Blackhall L J. Palliative educational outcome with implementation of PEACE tool integrated clinical pathway. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:279–295. doi: 10.1089/109662104773709404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B L. In: Post S, editor. Encyclopedia of Bioethics. Vol. 1. 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan Reference USA; 2004. “Autonomy.”. pp. 246–251.

- Epstein M. Why effective consent presupposes autonomous authorization: a counterorthodox argument. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:342–345. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.013227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D W. Anxiety, critical thinking and information processing during and after breast biopsy. Nurs Res. 1983;32:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D L, Starks H E, Cain K C, Uhlmann R F, Pearlman R A. Measuring preferences for health states worse than death. Med Decis Making. 1994;14:9–18. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9401400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried T R, Bradley E H, Towle V R, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier D E, Morrison R S. Autonomy reconsidered. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1087–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200204043461413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]