Abstract

Southeastern states are among the hardest hit by the HIV epidemic in this country, and racial disparities in HIV rates are high in this region. This is particularly true in our communities of interest in rural eastern North Carolina. Although most recent efforts to prevent HIV attempt to address multiple contributing factors, we have found few multilevel HIV interventions that have been developed, tailored or tested in rural communities for African Americans. We describe how Project GRACE integrated Intervention Mapping (IM) methodology with community based participatory research (CBPR) principles to develop a multi-level, multi-generational HIV prevention intervention. IM was carried out in a series of steps from review of relevant data through producing program components. Through the IM process, all collaborators agreed that we needed a family-based intervention involving youth and their caregivers. We found that the structured approach of IM can be adapted to incorporate the principles of CBPR.

Keywords: CBPR, Intervention mapping, HIV prevention intervention, rural African American communities

Background

In the United States (U.S.), the South is the region hardest hit by the HIV epidemic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006; Southern AIDS Coalition 2008). Although the region contains only 36% of the U.S. population, it accounts for more than half of persons living with HIV and 40% of new infections (Southern AIDS Coalition, 2008). Racial disparities in HIV rates are striking; although African Americans represent 19% of the regional population, more than half HIV/AIDS cases (54%) in the South occur among African Americans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006; Southern AIDS Coalition, 2008).

The disparate burden of HIV among African Americans in the U.S. is not due solely to individual-level behaviors. Social context contributes to the spread of HIV (Adimora & Schoenbach, 2005; Galea & Vlahov, 2002; Herbst et al., 2007) and may be particularly important in African American communities which tend to be socially segregated and characterized by higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and incarceration than other communities. These social and economic disparities act synergistically to increase the likelihood of high risk behaviors and overlap between individuals in low and higher risk sexual networks (Adimora et al., 2006; Farley, 2006). The impact of these disparities can be magnified for African Americans in rural communities where longstanding social and economic segregation are often present (Adimora et al., 2006).

Although early HIV research and prevention interventions focused on changing individual risk behaviors, most recent efforts attempt to address multiple contributing factors simultaneously. These multilevel interventions are complex, employing various intervention approaches simultaneously, making implementation, evaluation and dissemination of these interventions difficult (e.g. Fuller et al., 2007; Fullilove, 2000; NIMH Multisite HIV/STD Prevention Trial for African American Couples Group, 2008; Prado et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2006; Romero et al., 2006; Weeks et al., 2009 ). However, few multilevel HIV prevention interventions have been developed, tailored or tested in rural communities for African Americans or other racial groups (Coker-Appiah et al., In Press; King et al., 2008; Rhodes et al., 2006; Smith & DiClemente, 2000). Developing effective HIV prevention interventions that have broader, sustainable effects that extend beyond individual behavioral change remains an on-going challenge for the field (King et al., 2008; Robinson, 2005). Accomplishing these efforts in rural communities where the number of service providers and the HIV advocacy communities are often small, where populations tend to be spread out and in the context of more conservative values and HIV related stigma can make engaging community members more challenging (Thomas, Eng, Earp & Ellis, 2006).

In this paper, we describe the approach we used to develop a multilevel HIV prevention intervention in two rural counties in North Carolina. Researchers at the University of North Carolina with others who had worked in these two counties for several years on a variety of public health initiatives (e.g. Adimora et al., 2004; Adimora et al., 2006; Earp et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2001) responded to community concerns about the HIV epidemic’s disparate impact on African American communities and worked collaboratively to establish an academic-community partnership to address these concerns. To ensure that our intervention addressed critical factors influencing HIV risk in these communities and to maximize sustainability and community engagement, we integrated community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods with Intervention Mapping (IM), a structured approach to intervention design.

Intervention mapping (IM) has been used to develop health promotion programs and produces a framework that links health behavior theory and performance objectives with specific methods and strategies (Bartholomew, Parcel, & Kok, 2002; Hoelscher, Evans, Parcel, & Kelder, 2002; Markham, Tyrrell, Shegog, Fernandez, & Bartholomew, 2001; Murray, Kelder, Parcel, & Orpinas, 1998; Wolff et al., 2004). IM is not a partnership, we chose IM as our method of intervention development process using a structured approach that moves from theory to practice (Tortolero et al., 2005; World Population Foundation, 2008; Kok, 2009 ). Our academic-community partnership chose IM as our method of intervention development because, consistent with CBPR principles, IM allows maximal participation of all partners in the planning process; acknowledges the role of behavioral and environmental factors in health outcomes; and explicitly draws on health behavior theory as the basis for program development. Although a number of papers in the published literature describe the use of IM for public health intervention development (Fernandez, Gonzales, Tortolero-Luna, Partida, & Bartholomew, 2005; McEachan, Lawton, Jackson, Conner, Lunt, 2008), including HIV prevention interventions (Cote, Godin, Garcia, Gagnon, Rouleau, 2008; Van Kesteren, Kok, Hospers, Schippers, De Wildt, 2006; Wolfers, van den Hoek, Brug, de Zwart, 2007), we could find none that described the use of IM within a CBPR framework.

In this manuscript, we describe how we integrated IM methodology with CBPR principles to develop a multi-generational HIV prevention intervention for two rural African American communities. This paper will focus mainly on the process of integrating these two methodologies rather than on describing the resulting intervention in detail.

Method

Community Setting

North Carolina reports some of the highest rates of HIV in the Southern U.S. with almost two-thirds of these cases occurring among African Americans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005; North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). Our community-academic partnership, Project GRACE (Growing, Reaching, Advocating for Change and Empowerment) serves Nash and Edgecombe counties, two predominantly rural counties in eastern North Carolina. Both counties are experiencing some of the highest rates of HIV/AIDS in the state and the most significant HIV/STI disparities. Nash County ranked 16th and Edgecombe County 3rd among North Carolina’s 100 counties in the three-year average rate of new HIV cases for 2005–2007 (North Carolina Epidemiology and Special Studies Unit, 2007). In Nash County, 82% of people with HIV/AIDS in 2006 were African American, although only 34% of the county’s population was African American (Nash County Health Department, 2007; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). In Edgecombe County, 86% of HIV/AIDS cases were African American, where African Americans make up 58% of the county population (Edgecombe County Health Department, 2007; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000).

Community-Academic Partnership Structure

Project GRACE was formed in 2005 in response to community members’ concerns about the growing HIV problem in the two counties. Preexisting ties between the academic partners and community stakeholders in these counties facilitated the development of this partnership. In prior formative work, HIV disparities had been described as one of three major health concerns among community based organizations and lay community members. In addition, several stakeholders and community leaders from Nash and Edgecombe counties expressed a desire to collaborate with an academic center in their focus on the HIV epidemic in their counties. In recognition of this health crisis, the decision was made to create a community-academic partnership with the explicit mission of addressing health disparities in the two counties, with HIV as the initial focus.

The process for developing the Project GRACE partnership, the challenges in doing so and lessons learned have been described in detail elsewhere (Corbie-Smith et al., Under Review). In brief, to create our academic-community partnership, we used the staged approach to partnership development described by Florin, Mitchell and Stevenson (1993) (Bull et al., 1999; Corbie-Smith et al., Under Review). They describe four early stages of partnership development: initial mobilization; establishment of organizational structure; capacity building for action; and planning for action. These initial stages focus on the CBPR principles of engaging community partners, broadening the base of community support, identifying the strengths and capacity of community representatives, delineating roles for academic and community partners, ensuring shared decision making, developing organizational infrastructure, capacity-building to support subsequent action steps, and planning for action. In our approach, activities at each stage occurred in parallel with the intended result of reinforcing and strengthening the collaboration through a cyclical and iterative process of partnership development (Corbie-Smith et al., Under Review; Viswanathan et al., 2004).

The key tasks and activities we engaged in associated with the first steps in Florin’s model are shown in Table 1. During the initial mobilization, university investigators and community partners from each county reached out to community members through a series of open meetings to discuss the local HIV epidemic, assess the interest of other established community based organizations (CBOs) to address the problem, and discuss available funding mechanisms. After funding was obtained, a locally recruited community outreach specialist (COS) engaged a broad array of additional partners including general and key members of the target communities, leaders of local CBOs, public health agencies and multidisciplinary researchers from university campuses. We established an organizational structure involving a Consortium and Steering Committee. The Consortium includes broad community representation from the two counties to ensure community-level oversight of partnership activities. The 26 member Steering Committee is charged with the management and conduct of all project-related activities and is comprised of representatives from all subcontracting community partner organizations and community leaders in each county (Corbie-Smith et al., Under Review). The Consortium and Steering Committee provide a system of checks and balances on one another’s decisions and activities. Separate working subcommittees report to the Steering Committee and function to conduct the business of Project GRACE. Six subcommittees (Communications and Publications, Research and Design, Nominating, Bylaws, Events Planning and Fiscal and Budget) tackle logistical aspects of project activities with subcommittee members representing our broader membership and reporting back to the Steering Committee.

Table 1.

Stages and Tasks of Partnership Development

| Stage of partnership development | Examples of tasks associated with each stage |

|---|---|

| Initial mobilization |

|

| Establishment of organizational structure |

|

| Building capacity for action |

|

| Planning for action |

|

As one of our early partnership activities, we conducted formative research to identify community needs and assets as they related to HIV risk in the target community (Bartholomew et al., 2002; Green & Kreuter, 1999). This comprehensive approach gave us collective confidence that the interventions we developed would be based on a thorough understanding of the needs of the target population and would build on existing community capacity to ensure sustainability (Bartholomew et al., 2002; Green & Kreuter, 1999). In the sections that follow, we detail the process by which we integrated our CBPR approach with IM to develop our intervention.

Intervention Mapping

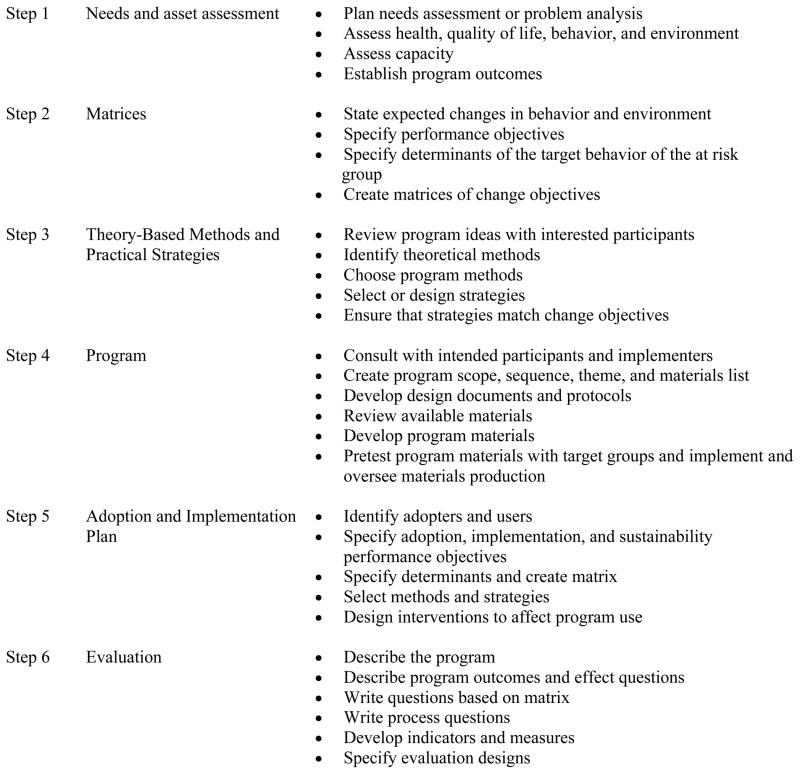

Intervention Mapping (IM) is carried out in a series of steps from review of relevant data through evaluation (Figure 1). We focus here on the first 4 steps related to intervention development (Bartholomew et al., 2002). Step 1 involves assessing needs and assets. Step 2 includes developing matrices of change objectives (i.e., intervention goals) and consists of the following tasks: defining health promoting behaviors (i.e., behavioral outcomes); specifying performance objectives for health promoting behaviors; deriving behavioral determinants of performance objectives from theory, literature, and practice; and specifying and creating a matrix of learning objectives to link performance objectives with specific determinants. Step 3 involves specifying intervention methods and translating methods into practical strategies. Step 4 includes producing program components.

Figure 1. Intervention Mapping Process1.

1 From Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH: Planning health promotion programs. An Intervention Mapping approach. 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass; 2006.

Step 1: Formative research on needs and assets

We conducted 11 focus groups during the spring and summer of 2006 with community youth ages 16 to 24, adults ages 25–45 and formerly incarcerated adults. We also conducted 37 key informant interviews in the fall and winter of 2006. The full methods have been described elsewhere (Cené, Akers, Lloyd, Albritton, Hammond & Corbie-Smith, Under Review; Coker-Appiah et al., In Press). We recruited through local CBOs using flyers, print and radio advertising, and snowball sampling. In keeping with our desire to involve community members throughout the research process, we recruited, hired and trained moderators, note takers and interviewers from the local communities. All were trained by a professional, African American owned, qualitative research firm to conduct the focus group and individual interviews. The moderator and individual interview guides were developed jointly by community and academic members of the Research and Design Subcommittee, one of the six subcommittees of the Steering Committee. The design and implementation of the coding strategy and all analyses were conducted with teams of analysts comprised of academic and community members to ensure validity of the findings. Through this intensive review and analysis of our assessment, we decided to focus on HIV/STI prevention in youth.

Step 2: Developing matrices of learning objectives

Preparing for Intervention Mapping: Co-Learning on applying health behavior theory

After collecting the formative data, we conducted IM with the entire Steering Committee and laymembers of the community in an intensive series of all-day workshops, small group conference calls, and in-person meetings of subgroups where all partners were involved in each step of the process, during May 2007 through January 2008. As one aspect of capacity building and co-learning to ensure that all partners understood the IM methods and had a working knowledge of health behavior theory, we conducted a half day primer for community partners, investigators and research staff that introduced the theoretical framework for several behavioral theories that could be relevant to our work and underscored the role of health behavior theory in development of effective interventions. We used written simplified summaries of a number of major theories (National Cancer Institute, 2005) supplemented with didactic and small group discussion. This provided an opportunity for collective discussion regarding the importance of theoretically grounding interventions, reviewing the relevance of constructs from different theoretical models as well as answering questions about and clarifying the IM process.

Intervention Mapping Workshop

The primer session on health behavior theory was followed by an intensive, two-day workshop that initiated step 2 of the intervention development process (i.e., matrix development). The first half day of the workshop included an overview of IM methods as well as a recap of the findings from the formative research. Training was conducted by a project staff person with prior training and experience using IM methods and by Steering Committee members who facilitated the small group sessions and the recap of research findings. The subsequent half-day session was a working group session in which small groups comprised of both academic and community partners brainstormed lists of intervention goals to target in order to address the high HIV rate in the target communities. The second day of the workshop, we reconvened as a large group to refine and determine the initial set of behavioral outcomes and to specify the associated performance objectives via consensus.

Post-Workshop Intervention Mapping Activities

In small groups comprised of academic and community partners, we worked on the remaining tasks of Step 2 over the next 4 months. These tasks included: refining performance objectives, identifying behavioral determinants and creating matrices. We accomplished these tasks through an iterative process in which groups of community and academic partners further refined the proximal behavioral and performance objectives as they defined the behavioral determinants. As the intervention matrices developed, each was reviewed by other subgroups and presented to the larger group of collaborators until we reached consensus on completeness. Consistent with our CBPR principles of co-learning and disseminating early products of our work, periodic presentations were made to the larger community at Consortium meetings. This allowed community members and leaders to remain aware of the project’s activities and provided an opportunity for them to provide structured feedback.

Final Matrices

Factors that may influence the desired outcomes are referred to as behavioral determinants of the outcome. Behavioral determinants answer the question, “Why do people engage in the behavior of interest?” and draws on behavioral theory to suggest the answer. Matrices are a grid of performance objectives (row headings) and behavioral determinants (column headings) for each behavioral outcome. In each matrix cell, the learning objectives are specified in response to the question: “What needs to be learned related to this determinant to achieve the performance objective?” For example: “What skills are needed to negotiate sexual abstinence?” The matrices display the answers to these questions for determinants of each performance objective.

Step 3: Select theory-based methods and strategies

The goal of Step 3 is to match intervention methods to the learning objectives, listed in Step 2, by answering the question, “How can we influence people to meet the learning objectives?” Intervention methods are based on behavioral and social science theories and directly address the determinants of behavior in any given intervention (Bartholomew, Parcel, & Kok, 2002). Methods are techniques for influencing change in those determinants. Strategies, on the other hand, are practical techniques for applying the appropriate methods for the target population and specific planned intervention. We again used sub-groups of academic and community partners to match intervention methods to the learning objectives.

Step 4: Produce program components and materials

This step in IM involves organizing strategies into a deliverable program and results in the actual design of the program, including producing the intervention training manuals and workbooks. As part of this task, we had to determine the program structure (i.e., scope and sequence), theme, channels for delivery, and program materials. Continuing with our CBPR framework for IM, we had a working group of community and academic partners develop the curriculum lessons and conducted a community wide pre-test event.

Results

Step 1: Needs and Asset Assessment: Focus Group and Key Informant Interviews

Detailed results from our assessment have been described elsewhere (Cené et. al., Under Review; Coker-Appiah et al., In Press; Corbie-Smith et al., Under Review). Participants described behavioral, social, and environmental factors thought to mediate the high HIV rates in their communities (see Table 2). They also made recommendations for what HIV prevention interventions, for this community, should look like (see Table 2). In our focus group and in-depth interviews, there was a clear message to focus on youth behavior. All respondents articulated the need to place those behaviors in the context of the family and community and noted individual and social factors that influence the sexual risk behaviors in youth in our target population. In order to reduce the rates of STIs and HIV, all collaborators agreed that a family-based intervention involving youth and their parents or primary caregivers (henceforth referred to as ‘caregivers’) was needed. Moreover, in order to promote sustainability beyond the duration of the program and to change social norms, we chose to use a LHA model in which individuals across generations (i.e. caregivers and youth) share HIV prevention messages with members of their community. Although there are a number of HIV prevention programs that involve both caregivers and youth (e.g. Chen et al., 2009; DiIorio et al, 2006; Stanton et al., 2004; Winett et al., 1992); most target only mothers or fathers, or they seek to improve sexual health outcomes only in one gender (Dancy, Crittenden & Freels, 2006; DiIorio et al., 2006; Gong et al., 2009; Hutchinson, Jemmott, Jemmott, Braverman, & Fong, 2003). Few are culturally-tailored for African American parents, and those that are focus on low-income or urban families (Dancy et al., 2006; McCormick et al., 2000).

Table 2.

Results from Community Needs Assessment and Intervention Recommendations

| Factors Mediating HIV Risk | Main Themes | Intervention Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral |

|

|

| Social |

|

|

| Environmental |

|

|

We also wanted to address the issue of sustainability and building on community strengths, for this reason we chose an intervention approach of youth-caregiver dyads serving as lay health advisors. We chose to use a Lay Health Advisor (LHA) model as an intervention framework because this model is adaptable, targets change at multiple levels, and builds on strong networks in rural African American communities. The LHA model has proven to be effective in developing both trust and the capacity of community members while building on various socio-cultural strengths of African American culture, thus enhancing opportunities for sustainability (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Raczynski et al., 2001; Thomas, 2006; Wolff et al., 2004). LHA HIV prevention programs have decreased risky sexual behaviors; decreased illicit drug use; increased health knowledge regarding HIV/AIDS; and led to more realistic perception of personal risk (Birkel et al., 1993; Diamond et al., 2009; Kelly et al., 1997; McQuiston, Choi-Hevel, & Clawson, 2001; Pearlman et al., 2002; Thomas, 2006). Importantly, LHA interventions provide continuous opportunities for training and capacity building among community members (Israel et al., 1998). A critical component of success of LHA interventions has been the use of CBPR methods during needs assessment and planning of interventions (Thomas, 2006; Viswanathan et al., 2004; Zuvekas, Nolan, Tumaylle, & Griffin, 1999). All partners felt that the LHA intervention model was in keeping with our overall partnership approach.

Step 2: Matrices of Learning Objectives

We established separate intervention goals for youth and their caregivers. The intervention goals for youth were to delay sexual initiation and improve engagement in responsible sexual behaviors for those who chose to be sexually active. The specific behavioral outcomes identified as necessary to achieve these goals were the following: abstinence from sex, condom use among sexually active youth, and healthy dating and relationship behaviors.

The intervention goals for caregivers were to improve parenting and communication skills. The specific behavioral outcomes identified as necessary to achieve these goals included: parental monitoring of adolescents’ social/dating activities and parental communication about sex and healthy dating relationships. We chose to focus on these parenting practices because they have been most consistently shown in prior research to be associated with improved reproductive health outcomes for youth (DeVore & Ginsburg, 2005; Meschke, Bartholomae, & Zentall, 2000; Perrino, Gonzalez-Soldevilla, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2000).

For each behavioral outcome for caregivers and youth, we specified an observable subset of behaviors, performance objectives, that would be necessary to achieve the target outcomes for both youth and caregivers (see Table 4). In considering our goals for the program, we collectively decided to employ the theory of planned behavior (TPB) to address individual-level factors (Ajzen, 2002) and a teaching model grounded in social cognitive theory (SCT) to address the influences of the social environment that contribute to risky sexual behaviors among African American adolescents (Bandura, 1986). The TPB, an extension of the theory of reasoned action, suggested that behavioral intention, the most proximal determinant of behavior, is determined conceptually by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral controls (or self efficacy). Subjective norms (social pressure to carry out or not carry out a behavior) are determined by normative beliefs (perceived behavioral expectations of important others) and the motivation to meet those expectations. Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to engage in the behavior, which can influence behavior directly or through behavioral intention (Ajzen, 1987; Ajzen, 2006). SCT integrates both determinants of personal behavior and methods of behavior change. SCT proposes that behaviors are performed due to complex interactions between environmental, personal and behavioral factors (Bandura, 1986). Personal factors include behavioral capability (knowledge and skill to perform a behavior), self efficacy, and outcome expectation. Environmental factors include social support and social networks. Our behavioral determinants reflect constructs from these theoretical models. Excerpts of sample matrices for caregivers and youth that resulted from these steps are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Excerpts from Sample Matrices

| Performance Objectives | Determinants | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Self efficacy | Skills | Attitudes | Perceived Norms | Outcome Expectations | Social Support | |

| Behavioral Outcome: “Caregivers will communicate with youth about dating” | |||||||

| PO.1. Decide to communicate with youth about sex, dating and relationships | PC.KNOW.1.i. List characteristics of healthy communication. PC.KNOW.1.ii. State the benefits of communication with their youth about sex and STIs. |

PC.SE.1.i. Caregivers will feel confident that they can successfully communicate with their youth about D/HR/SB | PC.ATT.1.i. Feel favorable about deciding to communicate with youth about D/HR/SB | PC.SS.1.i. Identify peers who are supportive of your decision to communicate with your youth about D/HR/SB | |||

| PO. 5. Discuss abstinence with youth. | PC.KNOW.5.i. State the definition of abstinence. | PC.SE.5.i. Express confidence in ability to communicate the importance of abstinence with youth. | PC.SKILLS.5.i. Demonstrate the ability to communicate the importance of abstinence to the youth. | PC.ATT.5.i. Feel positive about discussing abstinence with youth. | PC.PN.5.i. Recognize that other caregivers discuss abstinence with their youth. | PC.OE.5.i. State that discussing abstinence will reduce the likelihood that your youth engaging in risky sexual behavior. | PC.SS.5.i. Seek support from peers who support your discussion of abstinence with your youth. |

| Behavioral Outcome: “Youth will abstain from sex.” | |||||||

| PO.1. Decide not to have sex | AB.KNOW.1.i. Define different types of sex (vaginal, oral, anal). AB.KNOW.1.iii. Recognize abstinence is the only 100% effective way to avoid STI/HIV. |

AB.SKILLS.1.i. Demonstrate ability to make decision not have sex. | AB.SE.1.i. Express confidence in ability to decide not to have sex. | AB.NB.1.i. State significant others approve and respect decision not to have sex. AB.NB.1.ii. Recognize social status can be determined by characteristics other than sexual behavior. |

AB.PN.1.i. Recognize not all youth in community are having sex. AB.PN.1.iv. Recognize most parents feel it is important for youth not to have sex. |

AB.SESC.1.i. Recognize decision not to have sex will increase self-respect | AB.ATT.1.i. Feel good about decision not to have sex. |

| PO.5. Refuse to have sex. | AB.KNOW.5.i. Identify signs of being in a situation where it may be hard to say no to sex. AB.KNOW.5.ii. Recognize these signs as cues to employ refusal strategies. |

AB.SKILLS.5.i. Demonstrate ability to use refusal skills in multiple situations. | AB.SE.5.i. State confidence in being able to use refusal skills in a variety of situations. | AB.NB.5.i. State that significant others approve and respect your refusal to do things that you choose not to do (non-sex related behaviors). | --- | --- | AB.ATT.5.i. Express opinion that not having sex is highly important to you. |

Step 3: Theoretical-Basis Methods and Strategies

The intervention has two primary components: a curriculum for youth that focuses on abstinence, condom use, and healthy dating relationships; and a curriculum for caregivers that focuses on parental monitoring, communication about sexual health and healthy dating. Both curricula include social learning and cognitive behavioral methods in the education of caregivers and youth, including modeling of desired behaviors, guided practice, and elements that improve self efficacy in attaining goals and skills (Bartholomew et al., 2002). Both curricula provide practice opportunities to apply new skills in anticipated and difficult situations and opportunities for guided reflection. The sessions emphasize active learning using a variety of instructional strategies (e.g. games, small and large group discussion, skill practice, stories, and individual activities).

Step 4: Program Components and Materials

Description of the “Teach One, Reach One” Intervention

After collectively examining epidemiologic data, existing literature, health behavior theory, and the collected data on the needs and strengths of our communities, we designed an intervention that addresses multiple contributors to HIV/STI risk in African American youth. This multigenerational intervention addresses the individual, social network, and community levels of the social ecological framework (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988). By integrating community input throughout the development process and building on the strengths of our community (i.e. strong social networks and natural helpers), the intervention was designed with particular attention to cultural appropriateness, long-term sustainability within the community, and potential for dissemination to other communities and organizations.

Because our study design was innovative (i.e., training youth and adult dyads as LHAs to deliver a HIV prevention intervention), We drew explicitly from programs that have been demonstrated to be successful, emphasizing those that were tested in African Americans or rural populations. Curricular components were drawn from successful, evidence-based programs on HIV/STI prevention: “Focus on Kids,” “Safer Choices,” “Becoming a Responsible Teen,” “Making Proud Choices,” “Draw the Line, and “Real AIDS Prevention Program (Coyle, 1996; Kirby et al., 2004; Semaan, Lauby, O’Connell, & Cohen, 2003; St. Lawrence, Crosby, Brasfield, & O’Bannon, 2002; Stanton et al., 1996) In our review of existing tested programs, there were substantially more interventions that focused on youth than caregivers. To address the behavioral objectives for caregivers, we had to develop certain components or activities de novo or adapt activities using the theory based strategies and methods as a guide. The training sessions are sequential, with later sessions building on concepts of earlier ones. Integrated in each session are skills that LHAs will need to reach out to youth and adults around these issues.

We pre-tested the curricular components in a 1 day community-wide event. We pre-tested four youth and four caregiver sessions, focusing on those that were developed de novo or that were thought to be controversial (e.g., introduction and demonstration of condom use). Steering committee members and the community outreach specialist recruited 52 participants to take part in the pretest. For each session, two Steering Committee members were trained and served as facilitators to teach the caregiver and youth lessons, respectively. Two other Steering Committee members served as impartial observers during each session to record time, participant reactions to activities, successes and challenges in the sessions. At the conclusion of each session, facilitators led a structured debriefing with participants to elicit their feedback about the session content, the overall program objectives and the methods and activities used. This allowed us to also pre-test the process evaluation methods, to ensure the cultural relevance of debriefing questions and to pre-test the logistics of conducting all data collection activities. The subgroups working on the training sessions were given the written feedback to guide subsequent program revisions.

Discussion

Intervention mapping has been used successfully for planning health intervention programs, including several HIV interventions (Tortolero et al., 2005; Van Empelen, Kok, Schaalma, & Bartholomew, 2003). It has been used to provide a systematic process to develop new interventions as well as to adapt existing interventions to new populations in culturally appropriate ways (Tortolero et al., 2005). Most of the literature on IM include the methods and process, but none have described integrating the IM process into a CBPR framework. We chose IM because it could be used within the CBPR framework by including all partners in the process. We believed that a participatory approach to IM would enable us to better address the issues of HIV that are unique to rural African Americans, to design a more comprehensive program that fully involves caregivers in the reduction of adolescent sexual risk behaviors, and to develop a program that would address change beyond the individual level.

We found the IM process to be feasible to implement within our CBPR framework. Both community and academic partners were able to participate in every aspect of the process, from the design, conduct and analysis of the needs assessment, to developing the intervention matrices, applying the theories and strategies, and designing and pre-testing a deliverable program. This participatory approach resulted in the adoption of an LHA model for the intervention, which has been shown to be effective when working with African American and rural communities. For example, the decision to involve caregivers was a direct result of the participatory needs assessment analysis. The IM process, especially Steps 2 (matrix development) and 3 (selection of theory based methods and strategies), enabled us to find acceptable ways to fully involve caregivers in ways that had not been done in prior programs. And finally, the process resulted in a program that addresses multiple levels of social change.

Several challenges encountered are important to acknowledge. First, academic and community partners spoke different languages and came to the program development with different perspectives. University researchers were more grounded in health behavior theory as well as research and program planning methods; we had to find a way for community partners to feel comfortable with this new language. We developed the half day workshop to address this challenge by introducing the theoretical framework and behavioral theories and allowing the intervention development process to commence with both academic and community partners at the same table and with a similar knowledge foundation. This was a time intensive but necessary process, which we would recommend to anyone wanting to use IM in a participatory framework.

The second challenge was that community partners were far more versed than university researchers in what was feasible and culturally acceptable in our communities of interest. Community partners understood communities’ collective capacity, resources, informal relationships and which strategies would be most successful for effecting change. University partners had to learn about these social relationships and how to effectively integrate this reality with the research design for the program to be successful. This was addressed throughout the entire IM process, through community input and involvement at every step. This CBPR approach to IM led to the design of a program that was acceptable to all of the partners and culturally sensitive to the communities served.

Finally, one challenge faced by anyone planning to do community-based work is recognizing and planning for the relatively high turnover of staff at local CBOs. In this instance, staff turnover presented important challenges because new staff will, inevitably, lack knowledge about the academic-community partnership and will have missed participating in both the trust-building phase and workshops orienting them to research and program planning methods. This lack of familiarity can result in conflicts that challenge both programmatic and partnership success. We have addressed this by having multiple opportunities for continued involvement for individuals who are no longer employed by one of the partner organizations; for example through committee membership, ex officio positions on the Steering Committee and continued membership in the Consortium. We have also tried to incorporate into our academic partnership ways to preemptively address this. For example, having leadership of organizations who tend to experience less turn over sit on the Steering Committee to ensure their investment in the process and commitment to helping to orient and train new staff.

Conclusion

Intervention mapping provides a structured approach for HIV prevention program development. The inherent structure can be adapted to incorporate the principles of community based participatory research including co-learning on a topic of interest, sharing of the process and products of research, collective decision making, appreciation of unique expertise of all partners and research with the intended goal of social change.

Table 3.

Intervention Goals and associated Behavioral outcomes and Performance Objectives for Youth and Caregivers

| Intervention Goal | Behavioral Outcomes | Performance Objectives | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth |

|

|

|

| Caregiver |

|

|

|

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of all Steering Committee members and staff in the development of the Project GRACE Consortium: Ada Adimora, Larry Auld, Kelvin Barnhill, Reuben Blackwell, Hank Boyd III, John Braswell, Angela Bryant, Cheryl Bryant, Don Cavellini, Trinnette Cooper, Dana Courtney, Arlinda Ellison, Eugenia Eng, Loretta Evans, Jerome Garner, Vernetta Gupton, Davita Harrell, Shannon Hayes-Peaden, Stacey Henderson, Doris Howington, Clara Knight, Gwendolyn Knight, Taro Knight, Patricia Oxendine-Pitt, Donald Parker, Reginald Silver, Doris Stith, Jevita Terry, Yolanda Thigpen, Cynthia Worthy, Selena Youmans and Amy Sullivan. We would also like to acknowledge Stepheria Sallah for her technical support in preparing this manuscript.

This work was funded by grants from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24MD001671) and the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (UNC CFAR P30 AI50410) and from the National Center for Research Resources (KL2 RR-024154), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp.

Contributor Information

Giselle Corbie-Smith, Principal Investigator of Project GRACE and Associate Professor in the Departments of Social Medicine, Medicine and Epidemiology and Director of the Program on Health Disparities at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (UNC).

Aletha Akers, Assistant Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences at the Magee-Women’s Hospital at the University of Pittsburgh.

Connie Blumenthal, Project Manager of Project GRACE at the Sheps Center for Health Services Research, UNC-Chapel Hill.

Barbara Council, Business Administrator with the Community Enrichment Organization Family Resource Center in Tarboro, NC.

Mysha Wynn, Executive Director of Project Momentum, a community-based HIV/AIDS prevention and case management agency in Rocky Mount, NC

Melvin Muhammad, Ryan White Community Outreach Coordinator at Carolina Family Health Centers, Tarboro, NC. At the time the Intervention Mapping was conducted, he was the Community Outreach Coordinator at Project Momentum Inc.

Doris Stith, Executive Director of the Community Enrichment Organization Family Resource Center in Tarboro, NC.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson F, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Annuals of Epidemiology. 2004;14(3):155–160. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S115–122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Coyne-Beasley T, Doherty I, Stancil TR, et al. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(5):616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, traits, and actions: Dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 20. New York: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;22:665–683. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Constructing a TpB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. 2006 Retrieved June 15, 2007, from http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/

- Akers AY, Youmans S, Lloyd S, Coker-Appiah D, Banks B, Blumenthal C. Views of Young, Rural African Americans of the Role of Community Social Institutions’ Role in HIV Prevention. Journal of Health care for the Poor and Underserved. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0280. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, Parcel GS, Kok G. Intervention mapping: A process for developing theory-and evidence-based health education programs. Health Education & Behavior. 2002;25(5):564–568. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkel RC, Golaszewski T, Koman JJ, 3rd, Singh BK, Catan V, Souply K. Findings from the Horizontes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Education project: the impact of indigenous outreach workers as change agents for injection drug users. Health Education Quartley. 1993;20(4):523–538. doi: 10.1177/109019819302000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull SS, Rietmeijer C, Fortenberry JD, Stoner B, Malotte K, Vandevanter N, et al. Practice patterns for the elicitation of sexual history, education, and counseling among providers of STD services: results from the gonorrhea community action project (GCAP) Sex Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26(10):584–589. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199911000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Lunn S, Deveaux L, Li X, Brathwaite N, Cottrell L, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial of an adolescent HIV prevention program among Bahamian youth: effect at 12 months post-intervention. AIDS and behavior. 2009;13(3):499–508. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9511-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cené C, Akers AY, Lloyd SW, Albritton T, Hammond WP, Corbie-Smith G. Journal of General Internal Medicine. Social capital and HIV risk in rural African Americans. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1646-4. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease Surveillance, 2004. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial/ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS–33 States, 2001–2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55:121–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Coker-Appiah D, Akers A, Banks B, Albritton T, Leniek K, Wynn M, et al. In Their Own Voices: Rural African American Youth Speak Out About Community-Based HIV Prevention Interventions. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, in Action. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0099. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Adimora AA, Youmans S, Muhammad M, Blumenthal C, Ellison A, et al. Health Promotion Practice. Project GRACE: Building community- academic partnerships to address HIV disparities in rural African American communities. doi: 10.1177/1524839909348766. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote J, Godin G, Garcia PR, Gagnon M, Rouleau G. Program development for enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy among persons living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(12):965–975. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle K, Kirby D, Parcel G, Basen-Engquist K, Banspach S, Rugg D, et al. Safer Choices: a multicomponent school-based HIV/STD and pregnancy prevention program for adolescents. Journal of School Health. 1996;66(3):89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancy BL, Crittenden KS, Freels S. African-American adolescent females’ predictors of having sex. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association. 2006;17(2):30–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond S, Schensul JJ, Snyder LB, Bermudez A, D’Alessandro N, Morgan DS. Building Xperience: a multilevel alcohol and drug prevention intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43(3–4):292–312. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Resnicow K, McCarty F, De AK, Dudley WN, Wang DT, et al. Keepin’ it R.E.A.L.!: results of a mother-adolescent HIV prevention program. Nursing Research. 2006;55(1):43–51. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVore ER, Ginsburg KR. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2005;17(4):460–465. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000170514.27649.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earp JA, Eng E, O’Malley MS, Altpeter M, Rauscher G, Mayne L, et al. Increasing use of mammography among older, rural African American women: results form a community trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):646–54. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe County Health Department. Edgecombe County Statistical Analysis Query Report. 2007. Retrieved on April 1, 2007, from Edgecombe County Health Department database. [Google Scholar]

- Farley TA. Sexually transmitted diseases in the southeastern United States: Location, race, and social context. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(7):S58–S64. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175378.20009.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, Partida S, Bartholomew LK. Using intervention mapping to develop a breast and cervical cancer screening program for Hispanic farmworkers: Cultivando La Salud. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6(4):394–404. doi: 10.1177/1524839905278810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin P, Mitchell R, Stevenson J. Identifying training and technical assistance needs in community coalitions: a developmental approach. Health Education Research. 1993;8(3):417–432. doi: 10.1093/her/8.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Galea S, Caceres W, Blaney S, Sisco S, Vlahov D. Multilevel community-based intervention to increase access to sterile syringes among injection drug users through pharmacy sales in New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):117–24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove RE, Green L, Fullilove MT. The Family to Family program: a structural intervention with implications for the prevention of HIV/AIDS and other community epidemics. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S63–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Reports. 2002;117( Suppl 1):S135–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J, Stanton B, Lunn S, Deveaux L, Li X, Marshall S, et al. Effects through 24 months of an HIV/AIDS prevention intervention program based on protection motivation theory among preadolescents in the Bahamas. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):e917–28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health Promotion and Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. 3. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield; 1999. Health promotion and a framework for planning. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Beeker C, Mathew A, McNally T, Passin WF, Kay LS, et al. The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(4 Suppl):S38–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelscher DM, Evans A, Parcel GS, Kelder SH. Designing effective nutrition interventions for adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102(3 Suppl):S52–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Braverman P, Fong GT. The role of mother-daughter sexual risk communicaiton in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: a prospective study. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2003;33(2):98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, McAuliffe TL, Roffman RA, Solomon LJ, et al. Randomised, controlled, community-level HIV-prevention intervention for sexual-risk behaviour among homosexual men in US cities. Community HIV Prevention Research Collaborative. Lancet. 1997;350(9090):1500–1505. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King W, Nu’Man J, Fuller TR, Brown M, Smith S, Howell AV, et al. The diffusion of a community-level HIV intervention for women: lessons learned and best practices. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(7):1055–1066. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby DB, Baumler E, Coyle KK, Basen-Engquist K, Parcel GS, Harrist R, et al. The “Safer Choices” intervention: its impact on the sexual behaviors of different subgroups of high school students. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2004;35(6):442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok G. Intervention Mapping: Planning Theory and Evidence Based Health Promotion Programs. 2009 Retrieved on July 2009, from http://www.chps.ualberta.ca/pdfs/IM_Edmonton_2009.pdf.

- Lloyd SW, Akers A, Blumenthal C, Youmans S, Adimora A, Ellison A, et al. Politics, Ideology, and Public Health: Barriers to Appropriate Sex Education Curricula in Rural North Carolina Public Schools. (In Progress) [Google Scholar]

- Markham C, Tyrrell S, Shegog R, Fernandez M, Bartholomew LK. Partners in Asthma Management Program. In: Bartholomew L, Parcel G, Kok G, Gottlieb N, editors. Intervention Mapping: Designing Theory and Evidence Based Health Promotion Programs. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick A, McKay MM, Wilson M, McKinney L, Paikoff R, Bell C, Gillming G, Madison S, Scott R, et al. Involving families in an urban HIV preventive intervention: how community collaboration addresses barriers to participation. AIDS education and prevention: official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2000;12(4):299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachan RR, Lawton RJ, Jackson C, Conner M, Lunt J. Evidence, theory and context: Using intervention mapping to develop a worksite physical activity intervention. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:326. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuiston C, Choi-Hevel S, Clawson M. Protegiendo Nuestra Comunidad: empowerment participatory education for HIV prevention. Journal of Transcultural Nursing: official journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society/Transcultural Nursing Society. 2001;12(4):275–283. doi: 10.1177/104365960101200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschke LL, Bartholomae S, Zentall SR. Adolescent sexuality and parent-adolescent processes: Promoting healthy teen choices. Family Relations. 2000;49(2):143–154. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray N, Kelder S, Parcel G, Orpinas P. Development of an intervention map for a parent education intervention to prevent violence among Hispanic middle school students. Journal of School Health. 1998;68(2):46–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb07189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Insitute. NIH Publication No 05-3896. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. Theory at a Glance. [Google Scholar]

- Nash County Health Department. Nash County Statistical Analysis Query Report. 2007. Retrieved on April 1, 2007, from Nash County Health Department database. [Google Scholar]

- NIMH Multisite HIV/STD Prevention Trial for African American Couples Group. Formative Sudy to Develop the Eban Treatment and Comparison Interventions for Couples. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;49(Supplemental):S42–S51. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181844d57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Epidemiology and Special Studies Unit. North Carolina Statistical Analysis Query Report. 2007. Rretrieved May 1, 2007, from North Carolina HIV/STD database. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. North Carolina 2006 HIV/STD Surveillance Report. Raleigh, NC: N.C. Division of Public Health, N.C. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman DN, Camberg L, Wallace LJ, Symons P, Finison L. Tapping youth as agents for change: evaluation of a peer leadership HIV/AIDS intervention. Journal of Adolscent Health: official publication of the Society for Adolscent Medicine. 2002;31(1):31–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Gonzalez-Soldevilla A, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. The role of families in adolescent HIV prevention: a review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3(2):81–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1009571518900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Schwartz S, Lupei N, Szapocznik J. Predictors of Engagement and Retention into a Parent-Centered, Ecodevelopmental HIV Preventive Intervention for Hispanic Adolescents and their Families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;31(9):874–890. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raczynski JM, Cornell CE, Stalker V, Phillips M, Dignan M, Pulley L, et al. Developing community capacity and improving health in African American communities. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2001;322(5):269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montaño J, Remintz IM, Arceo R, Bloom FR, et al. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Develop an Intervention to Reduce HIV and STD Among Latino Men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(5):375–389. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RG. Community development model for public health applications: overview of a model to eliminate population disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6(3):338–346. doi: 10.1177/1524839905276036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L, Wallerstein N, Lucero J, Fredine HG, Keefe J, O’Connell J. Woman to Woman: Coming Together for Positive Change--using empowerment and popular education to prevent HIV in women. AIDS education and prevention: official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2006;18(5):390–405. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaan S, Lauby J, O’Connell AA, Cohen A. Factors associated with perceptions of, and decisional balance for, condom use with main partner among women at risk for HIV infection. Women & Health. 2003;37(3):53–69. doi: 10.1300/J013v37n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MU, DiClemente RJ. STAND: a peer educator training curriculum for sexual risk reduction in the rural South. Students Together Against Negative Decisions. Preventive Medicine. 2000;30(6):441–449. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern AIDS Coalition. Southern States Manifesto: Update 2008 HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the South. Alabama: Southern AIDS Coalition; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- St Lawrence JS, Crosby RA, Brasfield TL, O’Bannon RE., 3rd Reducing STD and HIV risk behavior of substance-dependent adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):1010–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton BF, Li X, Ricardo I, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Kaljee L. A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program for low-income African-American youths. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(4):363–372. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B, Cole M, Galbraith J, Li X, Pendleton S, Cottrel L, et al. Randomized trial of a parent intervention: parents can make a difference in long-term adolescent risk behaviors, perceptions, and knowledge. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158(10):947–55. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Eng E, Earp JA, Ellis H. Trust and collaboration in the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(6):540–7. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC. From slavery to incarceration: social forces affecting the epidemiology of sexually transmitted diseases in the rural South. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S6–10. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000221025.17158.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Parcel GS, Peters RJ, Jr, Escobar-Chaves SL, Basen-Engquist K, et al. Using intervention mapping to adapt an effective HIV, sexually transmitted disease, and pregnancy prevention program for high-risk minority youth. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6(3):286–298. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Population Estimates. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Van Empelen P, Kok G, Schaalma HP, Bartholomew LK. An AIDS risk reduction program targeting Dutch drug users: An Intervention Mapping approach to program planning. Health Promotion Practice. 2003;4:402–412. doi: 10.1177/1524839903255421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kesteren NMC, Kok G, Hospers HJ, Schippers J, de Wildt W. Systematic development of a self-help and motivational enhancement intervention to promote sexual health in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20(12):858–875. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, et al. AHRQ Publication Number 04-E022-1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2004. Community-Based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence (No. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks M, Convey M, Dickson-Gomez J, Li J, Radda K, Martinez M, Robles E. Changing Drug Users’ Risk Environments: Peer Health Advocates as Multi-level Community Change Agents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43(3–4):330–344. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winett RA, Anderson ES, Moore JF, Sikkema KJ, Hook RJ, Webster DA, et al. Family/media approach to HIV prevention: results with a home-based, parent-teen video program. Health Psychology: offical journal of the Di vision of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 1992;11(3):203–6. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfers MEG, van den Hoek C, Brug J, de Zwart O. Using intervention mapping to develop a programme to prevent sexually transmittable infections, including HIV, among heterosexual migrant men. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, Young S, Beck B, Maurana CA, Murphy M, Holifield J, et al. Leadership in a public housing community. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9(2):119–126. doi: 10.1080/10810730490425286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Population Foundation. IM Toolkit: for planning sexuality education programs. 2008 Retrieved July 2009, from http://www.wpf.org/documenten/20080729_IMToolkit_July2008.pdf.

- Zuvekas A, Nolan L, Tumaylle C, Griffin L. Impact of community health workers on access, use of services, and patient knowledge and behavior. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 1999;22(4):33–44. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]