Abstract

Genomic sequencing has made it clear that a large fraction of the genes specifying the core biological functions are shared by all eukaryotes. Knowledge of the biological role of such shared proteins in one organism can often be transferred to other organisms. The goal of the Gene Ontology Consortium is to produce a dynamic, controlled vocabulary that can be applied to all eukaryotes even as knowledge of gene and protein roles in cells is accumulating and changing. To this end, three independent ontologies accessible on the World-Wide Web (http://www.geneontology.org) are being constructed: biological process, molecular function and cellular component.

The accelerating availability of molecular sequences, particularly the sequences of entire genomes, has transformed both the theory and practice of experimental biology. Where once biochemists characterized proteins by their diverse activities and abundances, and geneticists characterized genes by the phenotypes of their mutations, all biologists now acknowledge that there is likely to be a single limited universe of genes and proteins, many of which are conserved in most or all living cells. This recognition has fuelled a grand unification of biology; the information about the shared genes and proteins contributes to our understanding of all the diverse organisms that share them. Knowledge of the biological role of such a shared protein in one organism can certainly illuminate, and often provide strong inference of, its role in other organisms.

Progress in the way that biologists describe and conceptualize the shared biological elements has not kept pace with sequencing. For the most part, the current systems of nomenclature for genes and their products remain divergent even when the experts appreciate the underlying similarities. Interoperability of genomic databases is limited by this lack of progress, and it is this major obstacle that the Gene Ontology (GO) Consortium was formed to address.

Functional conservation requires a common language for annotation

Nowhere is the impact of the grand biological unification more evident than in the eukaryotes, where the genomic sequences of three model systems are already available (budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, completed in 1996 (ref. 1); the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, completed in 1998 (ref. 2); and the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster, completed earlier this year3) and two more (the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana4 and fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe) are imminent. The complete genomic sequence of the human genome is expected in a year or two, and the sequence of the mouse (Mus musculus) will likely follow shortly thereafter.

The first comparison between two complete eukaryotic genomes (budding yeast and worm5) revealed that a surprisingly large fraction of the genes in these two organisms displayed evidence of orthology. About 12% of the worm genes (~18,000) encode proteins whose biological roles could be inferred from their similarity to their putative orthologues in yeast, comprising about 27% of the yeast genes (~5,700). Most of these proteins have been found to have a role in the ‘core biological processes’ common to all eukaryotic cells, such as DNA replication, transcription and metabolism. A three-way comparison among budding yeast, worm and fruitfly shows that this relationship can be extended; the same subset of yeast genes generally have recognizable homologues in the fly genome6. Estimates of sequence and functional conservation between the genes of these model systems and those of mammals are less reliable, as no mammalian genome sequence is yet known in its entirety. Nevertheless, it is clear that a high level of sequence and functional conservation will extend to all eukaryotes, with the likelihood that genes and proteins that carry out the core biological processes will again be probable orthologues. Furthermore, since the late 1980s, many experimental confirmations of functional conservation between mammals and model organisms (commonly yeast) have been published7-12.

This astonishingly high degree of sequence and functional conservation presents both opportunities and challenges. The main opportunity lies in the possibility of automated transfer of biological annotations from the experimentally tractable model organisms to the less tractable organisms based on gene and protein sequence similarity. Such information can be used to improve human health or agriculture. The challenge lies in meeting the requirements for a largely or entirely computational system for comparing or transferring annotation among different species. Although robust methods for sequence comparison are at hand13-15, many of the other elements for such a system remain to be developed.

A dynamic gene ontology

The GO Consortium is a joint project of three model organism databases: FlyBase16, Mouse Genome Informatics17,18 (MGI) and the Saccharomyces Genome Database19 (SGD). It is expected that other organism databases will join in the near future. The goal of the Consortium is to produce a structured, precisely defined, common, controlled vocabulary for describing the roles of genes and gene products in any organism. Early considerations of the problems posed by the diversity of activities that characterize the cells of yeast, flies and mice made it clear that extensions of standard indexing methods (for example, keywords) are likely to be both unwieldy and, in the end, unworkable. Although these resources remain essential, and our proposed system will continue to link to and depend on them, they are not sufficient in themselves to allow automatic transfers of annotation.

Each node in the GO ontologies will be linked to other kinds of information, including the many gene and protein keyword databases such as SwissPROT (ref. 20), Gen-Bank (ref. 21), EMBL (ref. 22), DDBJ (ref. 23), PIR (ref. 24), MIPS (ref. 25), YPD & WormPD (ref. 26), Pfam (ref. 27), SCOP (ref. 28) and ENZYME (ref. 29). One reason for this is that the state of biological knowledge of what genes and proteins do is very incomplete and changing rapidly. Discoveries that change our understanding of the roles of gene products in cells are published on a daily basis. To illustrate this, consider annotating two different proteins. One is known to be a transmembrane receptor serine/threonine kinase involved in p53-induced apoptosis; the other is known only to be a membrane-bound protein. In one case, the knowledge about the protein is substantial, whereas in the other it is minimal. We need to be able to organize, describe, query and visualize biological knowledge at vastly different stages of completeness. Any system must be flexible and tolerant of this constantly changing level of knowledge and allow updates on a continuing basis.

Similar considerations suggested that a static hierarchical system, such as the Enzyme Commission30 (EC) hierarchy, although computationally tractable, was also likely to be inadequate to describe the role of a gene or a protein in biology in a manner that would be either intuitive or helpful for biologists. The hierarchical EC numbering system for enzymes is the standard resource for classifying enzymatic chemical reactions. The EC system does not address the classification of non-enzymatic proteins or the ability to describe the role of a gene product within a cell; also, the system has little facility for describing diverse protein interactions. The vagueness of the term ‘function’ when applied to genes or proteins emerged as a particular problem, as this term is colloquially used to describe biochemical activities, biological goals and cellular structure. It is commonplace today to refer to the function of a protein such as tubulin as ‘GTPase’ or ‘constituent of the mitotic spindle’. For all these reasons, we are constructing three independent ontologies.

Three categories of GO

Biological process refers to a biological objective to which the gene or gene product contributes. A process is accomplished via one or more ordered assemblies of molecular functions. Processes often involve a chemical or physical transformation, in the sense that something goes into a process and something different comes out of it. Examples of broad (high level) biological process terms are ‘cell growth and maintenance’ or ‘signal transduction’. Examples of more specific (lower level) process terms are ‘translation’, ‘pyrimidine metabolism’ or ‘cAMP biosynthesis’.

Molecular function is defined as the biochemical activity (including specific binding to ligands or structures) of a gene product. This definition also applies to the capability that a gene product (or gene product complex) carries as a potential. It describes only what is done without specifying where or when the event actually occurs. Examples of broad functional terms are ‘enzyme’, ‘transporter’ or ‘ligand’. Examples of narrower functional terms are ‘adenylate cyclase’ or ‘Toll receptor ligand’.

Cellular component refers to the place in the cell where a gene product is active. These terms reflect our understanding of eukaryotic cell structure. As is true for the other ontologies, not all terms are applicable to all organisms; the set of terms is meant to be inclusive. Cellular component includes such terms as ‘ribo-some’ or ‘proteasome’, specifying where multiple gene products would be found. It also includes terms such as ‘nuclear membrane’ or ‘Golgi apparatus’.

Ontologies have long been used in an attempt to describe all entities within an area of reality and all relationships between those entities. An ontology comprises a set of well-defined terms with well-defined relationships. The structure itself reflects the current representation of biological knowledge as well as serving as a guide for organizing new data. Data can be annotated to varying levels depending on the amount and completeness of available information. This flexibility also allows users to narrow or widen the focus of queries. Ultimately, an ontology can be a vital tool enabling researchers to turn data into knowledge. Computer scientists have made significant contributions to linguistic formalisms and computational tools for developing complex vocabulary systems using reason-based structures, and we hope that our ontologies will be useful in providing a well-developed data set for this community to test their systems. The Molecular Biology Ontology Working Group (http://wwwsmi.stanford.edu/projects/bio-ontology/) is actively attempting to develop standards in this general field.

Biological process, molecular function and cellular component are all attributes of genes, gene products or gene-product groups. Each of these may be assigned independently and, indeed, we believe that simply recognizing that biological process, molecular function and cellular location represent independent attributes is by itself clarifying in many situations, as in the annotation of gene-expression data. The relationships between a gene product (or gene-product group) to biological process, molecular function and cellular component are one-to-many, reflecting the biological reality that a particular protein may function in several processes, contain domains that carry out diverse molecular functions, and participate in multiple alternative interactions with other proteins, organelles or locations in the cell.

The ontologies are developed for a generic eukaryotic cell; accordingly, specialized organs or body parts are not represented. Full integration of the ontologies with anatomical structures will occur as the ontologies are incorporated into each species’ database and are related to anatomical data within each database. GO terms are connected into nodes of a network, thus the connections between its parents and children are known and form what are technically described as directed acyclic graphs. The ontologies are dynamic, in the sense that they exist as a network that is changed as more information accumulates, but have sufficient uniqueness and precision so that databases based on the ontologies can automatically be updated as the ontologies mature. The ontologies are flexible in another way, so that they can reflect the many differences in the biology of the diverse organisms, such as the breakdown of the nucleus during mitosis. In this way the GO Consortium has built up a system that supports a common language with specific, agreed-on terms with definitions and supporting documentation (the GO ontologies) that can be understood and used by a wide biological community.

Examples of GO annotation

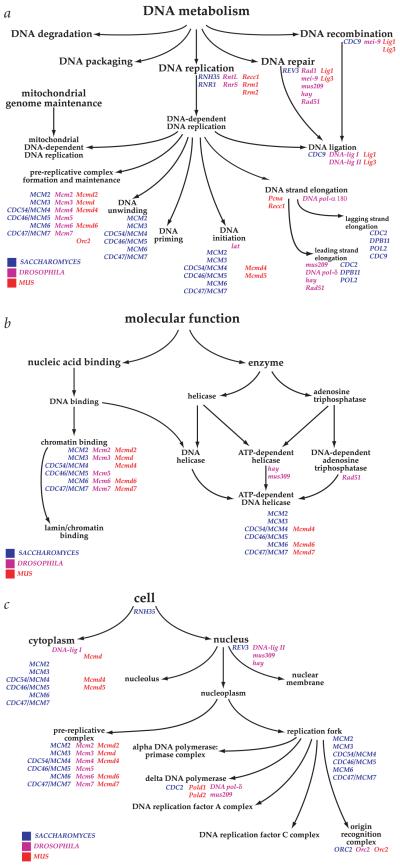

As one example, consider DNA metabolism, a biological process carried out by largely (but not entirely) shared elements in eukaryotes. The part of the process ontology (with selected gene names from S. cerevisiae, Drosophila and M. musculus) shown is largely one parent to many children (Fig. 1a). One notable exception is the process of DNA ligation, which is a child of three processes, DNA replication, DNA repair and DNA recombination. The yeast gene product Cdc9p is able to carry out the ligation step for all three processes, whereas it is uncertain whether the same enzyme is used in the other species. From the point of view of the ontology, it matters not, and a computer (or a human searcher) will find the appropriate nodes in either case using as the query either the enzyme, the gene name(s) or the GO term (or, if available, the unique GO identifier, in this case, GO:0003910).

Fig. 1.

Examples of Gene Ontology. Three examples illustrate the structure and style used by GO to represent the gene ontologies and to associate genes with nodes within an ontology. The ontologies are built from a structured, controlled vocabulary. The illustrations are the products of work in progress and are subject to change when new evidence becomes available. For simplicity, not all known gene annotations have been included in the figures. a, Biological process ontology. This section illustrates a portion of the biological process ontology describing DNA metabolism. Note that a node may have more than one parent; for example, ‘DNA ligation’ has three parents, ‘DNA-dependent DNA replication’, ‘DNA repair’ and ‘DNA recombination’. b, Molecular function ontology. The ontology is not intended to represent a reaction pathway, but instead reflects conceptual categories of gene-product function. A gene product can be associated with more than one node within an ontology, as illustrated by the MCM proteins. These proteins have been shown to bind chromatin and to possess ATP-dependent DNA helicase activity, and are annotated to both nodes. c, Cellular component ontology. The ontologies are designed for a generic eukaryotic cell, and are flexible enough to represent the known differences between diverse organisms.

Also shown are the molecular function ontology for the MCM protein complex members that are known to regulate initiation of DNA replication in the three organisms (Fig. 1b), and a portion of the cellular component ontology for these proteins (Fig. 1c). These ontologies reflect the finding that Mcm2–7 proteins are components of the pre-replicative complex in several model organisms, as well as sometimes localizing to the cytoplasm30. The ontology supports both biological realities, and yet the molecular functions and the biological processes of the MCM homologues are conserved nevertheless.

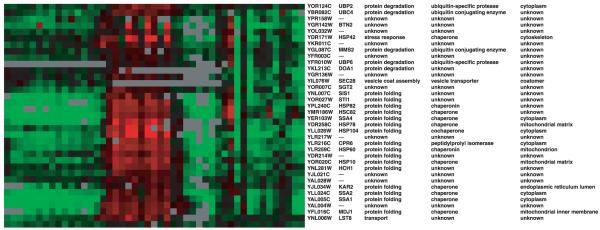

The usefulness of the GO ontologies for annotation received its first major test in the annotation of the recently completed sequence of the Drosophila genome. Little human intervention was required to annotate 50% of the genes to the molecular function and biological process ontologies using the GO method. Another use for GO ontologies that is gaining rapid adherence is the annotation of gene-expression data, especially after these have been clustered by similarities in pattern of gene expression32,33. The results of clustering about 100 yeast experiments (of which about half are shown; Fig. 2) grouped together a subset of genes which, by name alone, convey little to most biologists. When the full short GO annotations for process, molecular function and location are added, however, the biological reason and import of the co-expression of these genes becomes evident.

Fig. 2.

Correspondence between hierarchical clustering of expression microarray experiments with GO terms. The coloured matrix represents the results of clustering many microarray expression experiments32. In the matrix, each row represents the yeast gene described to the right, and each column represents the expression of that gene in a particular microarray hybridization. For each gene in the matrix, the table at right lists the systematic ORF name, the standard gene name (if known), and the GO biological process, molecular function and cellular component annotations for that gene. The GO annotations suggest that this experimental expression cluster groups gene products involved in the biological process of protein folding. In contrast, the molecular function and cellular component annotations of these gene products correlate less well with the clustered expression patterns of these gene products.

The GO project is currently using a flat file format to store the ontologies, definitions of terms and gene associations. The ontologies, gene associations, definitions and documentation are available from the GO web site (http://www.geneontology.org), which also describes the principles and objectives used by the project. The ontologies are by no means complete. They are being expanded during the association of gene products from the collaborating databases and we expect them to continue to evolve for many years. GO requires that all gene associations to the ontologies must be attributed to the literature; for each citation the type of evidence will be encoded. As of early April 2000 there were 1,923, 2,094 and 490 nodes in the process, function and component ontologies, respectively. The three organism databases have made substantial progress to link gene products. Thus far the process, function and component ontologies have associations with 1,624, 1,602 and 1,577 yeast genes; 741, 2,334 and 1,061 fly genes; and 1,933, 2,896 and 1,696 mouse genes, respectively. A running table of these statistics can be found at the web site.

The GO concept is intended to make possible, in a flexible and dynamic way, the annotation of homologous gene and protein sequences in multiple organisms using a common vocabulary that results in the ability to query and retrieve genes and proteins based on their shared biology. The GO ontologies produce a controlled vocabulary that can be used for dynamic maintenance and interoperability between genome databases. The ontologies are a work in progress. They can be consulted at any time on the World-Wide Web; indeed, their availability to human and machine alike is essential to maintain their flexibility and allow their evolution along with increased understanding of the underlying biology. It is hoped that the GO concepts, especially the distinctions between biological process, molecular function and cellular component, will find favour among biologists so that we can all facilitate, in our writing as well as our thinking, the grand unification of biology that the genome sequences portend.

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Fasman and M. Rebhan for useful discussions, and Astra Zeneca for financial support. SGD is supported by a P41, National Resources, grant from National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) grant HG01315; MGD by a P41 from NHGRI grant HG00330; GXD by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant HD33745; and FlyBase by a P41 from NHGRI grant HG00739 and the Medical Research Council, London.

References

- 1.Goffeau A, et al. Life with 6000 genes. Science. 1996;274:546. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Worm Sequencing Consortium. The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams MD, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meinke DW, et al. Arabidopsis thaliana: a model plant for genome analysis. Science. 1998;282:662–682. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chervitz SA, et al. Using the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) for analysis of protein similarities and structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:74–78. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin GM, et al. Comparative genomics of the eukaryotes. Science. 2000;287:2204–2215. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang Z, Kuo T, Shen J, Lin RJ. Biochemical and genetic conservation of fission yeast Dsk1 and human SR protein-specific kinase 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:816–824. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.816-824.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vajo Z, et al. Conservation of the Caenorhabditis elegans timing gene clk-1 from yeast to human: a gene required for ubiquinone biosynthesis with potential implications for aging. Mamm. Genome. 1999;10:1000–1004. doi: 10.1007/s003359901147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohi R, et al. Myb-related Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc5p is structurally and functionally conserved in eukaryotes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:4097–4108. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassett DE, Jr, et al. Genome cross-referencing and XREFdb: implications for the identification and analysis of genes mutated in human disease. Nature Genet. 1997;15:339–344. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kataoka T, et al. Functional homology of mammalian and yeast RAS genes. Cell. 1985;40:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Botstein D, Fink GR. Yeast: an experimental organism for modern biology. Science. 1988;240:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.3287619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrade MA, et al. Automated genome sequence analysis and annotation. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:391–412. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischmann W, Moller S, Gateau A, Apweiler R. A novel method for automatic functional annotation of proteins. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:228–233. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The FlyBase Consortium The FlyBase database of the Drosophila Genome Projects and community literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:85–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blake JA, et al. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): expanding genetic and genomic resources for the laboratory mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:108–111. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ringwald M, et al. GXD: a gene expression database for the laboratory mouse—current status and recent enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:115–119. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ball CA, et al. Integrating functional genomic information into the Saccharomyces Genome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:77–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:45–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson DA, et al. GenBank Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:15–18. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker W, et al. The EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:19–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tateno Y, et al. DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) in collaboration with mass sequencing teams. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:24–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker WC, et al. The Protein Information Resource (PIR) Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:41–44. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mewes HW, et al. MIPS: a database for genomes and protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:37–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costanzo MC, et al. The Yeast Proteome Database (YPD) and Caenorhabditis elegans Proteome Database (WormPD): comprehensive resources for the organization and comparison of model organism protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:73–76. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bateman A, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:263–266. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo Conte L, et al. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:257–259. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bairoch A. The ENZYME database in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:304–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enzyme Nomenclature. Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enyzmes. NC-IUBMB. Academic; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tye BK. MCM proteins in DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:649–686. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eisen M, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spellman PT, et al. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:3273–3297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]