Abstract

Although extremely rare, the presence of ectopic thyroid tissue in the submandibular region should be considered in the differential diagnosis of tissue masses in the cervical region. Diagnosis is confirmed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy and exclusion of malignancy should be confirmed by histopathologic analysis of the lesion. In general, surgery is the treatment of choice. A rare case of ectopic thyroid in the right submandibular region is reported; it was diagnosed after total thyroidectomy and successfully treated through surgery.

Keywords: Ectopic thyroid, Thyroid dysgenesis, Head and neck neoplasms, Surgery, Neck, Differential diagnosis

Introduction

Embryologically, the thyroid gland is derived from a median cluster of cells and from two lateral cell clusters [1–5]. The median portion produces the largest part of the thyroid parenchyma while the lateral portions are derived from the fourth pharyngeal pouch accounting for 1–30% of the total thyroid weight [1, 5]. A number of anomalies can develop during thyroid formation [2, 5], including ectopia of the thyroid tissue, a rare entity [3, 5–7], which may or may not coexist with a normal thyroid gland [3, 5, 6].

Failure in the median descent often results in a lingual thyroid [1, 4]. In some rare cases, the lack of merging of the lateral cell clusters with the median can cause a lateral ectopic thyroid gland [1, 3]; when this occurs thyroid tissue is located in the submandibular region [1, 3, 4, 7–10].

The present paper is aimed at describing a rare case of ectopic thyroid in the right submandibular region, in a patient whom previously had a total thyroidectomy for a colloid goiter.

Case Report

A 37-year-old female was referred to Department of Surgery at Universidade de Marília (UNIMAR) with a 1-month history of a mass in the right lateral region of the neck and nodules in the submental region. She did not have pain or related symptoms. The patient denied smoking and alcohol consumption.

Three years previously the patient had undergone a previous total thyroidectomy due to a benign disease—she was prescribed levothyroxine sodium 125 mcg orally daily. Before the thyroidectomy, a scintigraphy was carried out with pertechnetate-99mTc, revealing a cold nodule in the isthmus of the thyroid. Given the clinical presentation, we reviewed the previous scintigraphic examination and found a lesion taking radiopharmaceuticals in the right submandibular region (Fig. 1).

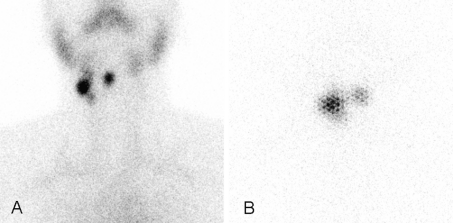

Fig. 1.

Scintigraphy with 99mTc-Pertechnetate in anterior projection of cervical region revealing uptake in the right submandibular region (arrow), corresponding to the anatomical location of the palpable nodule and on the neck midline, suggesting functioning thyroid tissues

The physical examination revealed a painless, mobile 2 cm palpable nodule in the region of the right carotid triangle/right submandibular area and another 1 cm nodule in the hyoid region. Ultrasonography of the cervical region showed an ovoid hypoechoic nodule, with a small central cystic area, with accurate limits and regular contours, measuring 1.4 × 1.0 cm, in the right median jugular-carotid chain.

Scintigraphy with 99mTc-Pertechnetate and with iodine-131, showed uptake of radiopharmaceuticals in the right submandibular region and in the neck midline, in the same location of the palpable nodules (Fig. 2). The study results were interpreted as presence of functioning thyroid tissues in the aforementioned regions.

Fig. 2.

Scintigraphies in anterior projection of cervical region, showing uptake in the right submandibular region and in neck midline, corresponding to anatomical location of palpable nodules. a Scintigraphy with 99mTc-Pertechnetate. b Scintigraphy with iodine-131

A fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the right cervical mass was performed and showed small cells with acidophilic cytoplasm, containing regular oval nuclei, with delicate evenly distributed chromatin. These cells were isolated or formed small nests, frequently resembling follicular structures. Presence of amorphous homogeneous material consistent with colloid was also observed (Fig. 3).

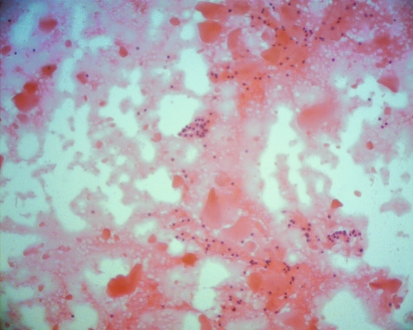

Fig. 3.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of right lateral cervical mass, showing a cytologic picture consistent with thyroid tissue (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification 40×)

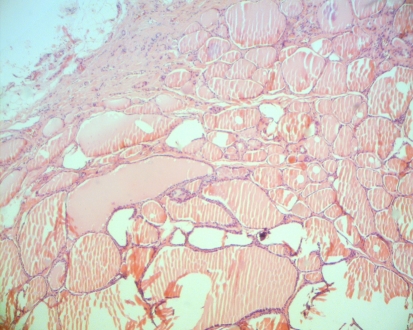

Since a malignant process could not be excluded, the patient underwent surgical excision of the lesion. In the right submandibular region a 2.5 × 2.0 cm encapsulated, solid nodular lesion was dissected and resected. Pathologic examination confirmed the suspicion of ectopic thyroid tissue, with no evidence of malignancy (Fig. 4). Microscopic examination revealed thyroidal tissue formed by macro-follicles and small cysts, compatible with hyperplasic pattern. The lining epithelium of these follicles ranged from flat to cuboidal. The cytoplasm scarce and nuclei were regular and normochromatic, without presence of nuclear grooves and/or pseudo-inclusions. Capsular and vascular invasion were not observed.

Fig. 4.

Photomicrograph of surgical specimen from submandibular region. Thyroid tissue showing different sizes of follicles with no signs of malignancy (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification 20×)

Discussion

Ectopic thyroid is defined as thyroid tissue not anterolateral to the second, third and fourth tracheal rings, in the midline [1, 3, 5, 9]. It is the most common form of thyroid dysgenesis, accounting for 48–61% of all cases [6]. Although its incidence is not known, studies on necropsy suggest that 7–10% of the adults can be asymptomatic carriers of thyroid tissue in the thyroglossal duct path [5, 6, 9].

The first case of ectopic thyroid was published in 1869 by Hickman, who described a lingual thyroid in a newly-born baby that underwent suffocation 16 h after birth as a consequence of a tissue mass that caused upper airway obstruction [3, 9].

Ectopic thyroid tissue usually occurs in the midline, from the foramen caecum to the mediastinum [1, 5, 7, 9] as a result of abnormal median migration and is rarely present lateral [1, 10]. A lingual location is most common, accounting for 90% of the reported cases [1, 3, 5, 6, 8–10]. Other sites rarely involved are the mediastinum, lungs, porta-hepatis system, duodenum, esophagus, heart, breasts, and intra-tracheal area [1–8]. Presence of ectopic thyroid tissue in the submandibular region is extremely rare [1, 3, 4, 7–10]. According to a recent study [8], similar cases of ectopic thyroid tissue have been reported in submandibular space.

Ectopic thyroid along the line of the cervical midline can be explained by non-migration or by excessive migration of thyroid tissue [1, 3, 6, 8]. On the other hand, lateral cervical location has been related to non-fusion of lateral buds of the fourth branchial pouches during the seventh week of embryonic life [1, 3, 8].

Until a few decades ago, cases of ectopic thyroid located in the lateral cervical region were considered as malignant tissue and were named as “lateral aberrant thyroid” because it was thought that these represented metastases from thyroid carcinoma [6, 9, 11]. From 1942 on, it had been believed that the presence of “lateral aberrant thyroid” represented metastases of thyroid primary carcinomas [11–13]. However, later reports showed the presence of normal thyroid ectopic tissue in these supposed “aberrant tumors” [3–10, 14, 15]. A recent study [7] reviewed 10 cases of ectopic thyroid in the submandibular region and reported a female predilection (81.81%) with and age range of 4–81 years.

From a clinical standpoint, patients present with a lateral cervical mass, palpable, mobile and painless [1–3, 6–10] that can be associated with thyroid hyperfunction or hypofunction [4]. Diseases that affect the normal thyroid gland can also affect the ectopic tissue [2–5], but benign or malignant neoplastic alterations that affect the ectopic thyroid tissue are very rare [5, 6]. Less than 1% of ectopic thyroids are reported to have malignant transformation and include all histologic variants with the exception of medullary carcinoma [14, 16]. Papillary carcinoma is the most common histologic type, accounting for approximately 85% of the cases [16].

In most cases of thyroidal ectopia in the submandibular region, the histopathologic evaluation reveals different sized follicles [3, 4, 7, 9, 15], compatible with a hyperplastic pattern [1, 3–6, 9] and that may be encapsulated [3, 7, 15], and/or show cystic degeneration, hemorrhage [4], fibrosis [5] or calcification [5, 8]. Cases of follicular adenomas with hemorrhage, calcification and fibrosis are more rare [10].

In cases of lateral ectopic thyroidal tissue on the neck, metastases should be excluded [1]. Parameters to differentiate between primary benign and malignant neoplasia of ectopic thyroid tissue are the same as used in primary tumors. To diagnose thyroid follicular carcinoma, vascular invasion and/or capsular rupture should be identified [17]. To differentiate from thyroid papillary carcinoma, nuclear characteristics should be excluded (ground-grass appearance, irregularity of nuclear contours, grooves, pseudo-inclusions) [17].

Although rare, diagnosis of ectopic thyroid [3, 6, 7, 9, 10] should be considered in the investigation of submandibular masses [1, 4, 6–10]. In the submandibular region, ectopias are clinically indistinguishable from other pathologies, such as tumors of the salivary glands or cysts [7]. In addition to clinical history and physical examination, ultrasonography is also useful for initial assessment [6, 10].

Scintigraphies are very useful because the iodine-131 uptake indicates the presence of functioning cells in a thyroid with high specificity. Scintigraphies also show presence of or absence of topic thyroid. Other image studies, such as computerized tomography and magnetic resonance may be needed for the local-regional evaluation [6, 9].

In cases of lateral cervical ectopic thyroid, the simultaneous occurrence of topic thyroid is rare [4, 8, 9]. When this occurs, there are diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties because only the ectopic tissue may be functional [4, 8, 9] up to 70% of cases [7]. Identification of presence or absence of eutopic thyroid gland should be considered for choosing the best treatment in these cases [8] since an inaccurate preoperative diagnosis can result in hypothyroidism [4, 8].

In the current case, after initial surgery (total thyroidectomy carried out in another service), thyroid function tests detected hypothyroidism and replacement therapy was implemented. Since a right submandibular mass was detected 3 years after the total thyroidectomy, the previous scintigraphy examination was reviewed, and although not noted on the report, uptake was present in the right lateral cervical region. It is possible that the decline in synthesis and secretion of the thyroid hormone, after total thyroidectomy, had increased hypophyseal production of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Therefore, high levels of this hormone may have stimulated growth of ectopic submandibular tissue [10], emphasizing the submandibular lesion that was asymptomatic in the thyroidectomy time and that was not taken into account in the first scintigraphy. Since replacement therapy was carried out with levothyroxine after thyroidectomy and during clinical follow up, this is a questionable speculative hypothesis.

There are no clinical, laboratory, or imaging parameters that may assist in determining the nature of this kind of lesions [2, 15]. Generally, diagnosis of ectopic thyroid is confirmed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy and, in some cases, differentiation between a benign and a malignant lesion is made only through histologic assessment [2, 4–6, 15], as was the case reported in the present paper.

The treatment of ectopic thyroid depends on factors such as mass size, local symptoms, age of the patient, functional status of thyroid gland and complications (ulceration, hemorrhage and neoplasia) [6, 10]. In cases of submandibular involvement, the therapeutic approach should be based on surgical excision with histopathologic evaluation of the mass [2–6, 8]. Although rare, there are cases of neck masses suspected of being ectopic thyroid tissue and later confirmed as metastases of thyroid carcinoma [1–3] and also cases where the ectopia may harbor a primary malignant neoplasia [1, 2, 13, 16].

Conclusion

Cases of ectopic thyroid in the submandibular region are rare and should be suspected in patients with presence of cervical lateral masses, with or without presence of normally located thyroid. The option of the surgical resection and pathologic assessment represents the most appropriate therapeutic option because such lesions may harbor a primary cancer or metastases of hidden thyroid cancer.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest None

References

- 1.Choi JY, Kim JH. A case of an ectopic thyroid gland at the lateral neck masquerading as a metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23(3):548–550. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.3.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fumarola A, Trimboli P, Cavaliere R, et al. Thyroid papillary carcinoma arising in ectopic thyroid tissue within a neck branchial cyst. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang TS, Chen HY. Dual thyroid ectopia with a normally located pretracheal thyroid gland: case report and literature review. Head Neck. 2007;29(9):885–888. doi: 10.1002/hed.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mace AT, McLaughlin I, Gibson IW, et al. Benign ectopic submandibular thyroid with a normotopic multinodular goitre. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(9):739–740. doi: 10.1258/002221503322334648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kousta E, Konstantinidis K, Michalakis C, et al. Ectopic thyroid tissue in the lower neck with a coexisting normally located multinodular goiter and brief literature review. Hormones (Athens) 2005;4(4):231–234. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.11163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasiru Akanmu I, Mobolaji Adewale O. Lateral cervical ectopic thyroid masses with eutopic multinodular goiter: an unusual presentation. Hormones (Athens) 2009;8(2):150–153. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babazade F, Mortazavi H, Jalalian H, et al. Thyroid tissue as a submandibular mass: a case report. J Oral Sci. 2009;51(4):655–657. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zieren J, Paul M, Scharfenberg M, et al. Submandibular ectopic thyroid gland. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17(6):1194–1198. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000246502.69688.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amoodi HA, Makki F, Taylor M, et al. Lateral ectopic thyroid goiter with a normally located thyroid. Thyroid. 2010;20(2):217–220. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abellán Galiana P, Cámara Gómez R, Campos Alborg V, et al. Dual ectopic thyroid: subclinical hypothyroidism after extirpation of a submaxillary mass. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2009;28(1):26–29. doi: 10.1016/S0212-6982(09)70213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabinov CR, Ward PH, Pusheck T. Evolution and evaluation of lateral cystic neck masses containing thyroid tissue: “lateral aberrant thyroid” revisited. Am J Otolaryngol. 1996;17(1):12–15. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(96)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambola-Cabrer I, Fernández-Real JM, Ricart W, et al. Ectopic thyroid tissue presenting as a submandibular mass. Head Neck. 1996;18(1):87–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199601/02)18:1<87::AID-HED11>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escofet X, Khan AZ, Mazarani W, et al. Lessons to be learned: a case study approach. Lateral aberrant thyroid tissue: is it always malignant? J R Soc Promot Health. 2007;127(1):45–46. doi: 10.1177/1466424007073207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong RJ, Cunningham MJ, Curtin HD. Cervical ectopic thyroid. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19(6):397–400. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feller KU, Mavros A, Gaertner HJ. Ectopic submandibular thyroid tissue with a coexisting active and normally located thyroid gland: case report and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90(5):618–623. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.108804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumoto K, Watanabe Y, Asano G. Thyroid papillary carcinoma arising in ectopic thyroid tissue within a branchial cleft cyst. Pathol Int. 1999;49(5):444–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmid KW, Farid NR. How to define follicular thyroid carcinoma? Virchows Arch. 2006;448(4):385–393. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]