Abstract

Ossifying fibroma (OF) is a fibro-osseous tumor that usually occurs in young people and arises in the craniofacial bones. We report a case of a 15-year-old boy who developed progressive proptosis and hypertelorism and was found to have a mid-face and skull base tumor, initially diagnosed as psammomatoid meningioma. The tumor recurred and the resected specimen revealed a unique OF having trabecular and psammomatoid features. The clinical, radiographic, histopathologic findings and differential diagnoses of the case are presented.

Keywords: Juvenile ossifying fibroma, Psammomatoid ossifying fibroma, Meningioma, Trabecular ossifying fibroma, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF) is a group of heterogeneous, benign fibro-osseous tumors of the craniofacial skeleton in young people. According to the WHO [1], JOF may present as one of two histologic variants: juvenile psammomatoid ossifying fibroma (JPOF) and juvenile trabecular ossifying fibroma (JTOF). JPOF usually occurs in the orbital bones, paranasal sinuses, mandible, and has been reported in the skull. Although rare, primary extracranial meningiomas have been reported occurring in the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx [2–4]. Furthermore, the distinction between JPOF and psammomatoid meningiomas (PM) arising in the craniofacial bones can be challenging. Herein we present the unique combination of both trabecular and psammomatoid patterns in a JOF, mimicking PM.

Case Report

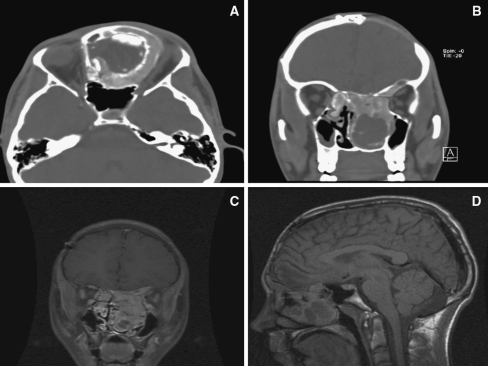

A 15-year-old male presented to the clinic with a 1-month history of moderate to severe proptosis on the left side and headache. On physical examination, he showed proptosis of the left eye and moderate hypertelorism. His medical and family histories were unremarkable. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed a mid-facial mass, predominately involving the nasal cavity with extension from the skull base into the anterior cranial fossa (Fig. 1a–d). He underwent a bifrontal craniotomy with extradural resection of anterior skull base and removal of the mid-face tumor. After an uncomplicated postoperative course, the patient was discharged.

Fig. 1.

a–d Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and brain revealed a mid-facial mass, predominately involving the nasal cavity with extension from the skull base into the anterior cranial fossa

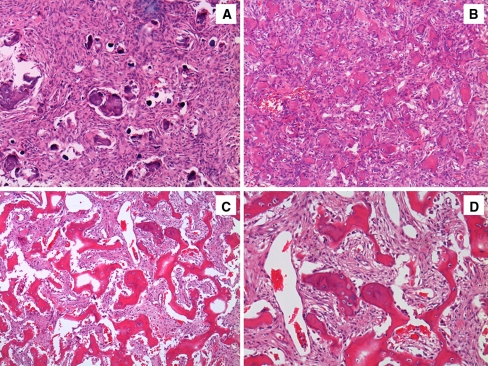

Gross examination of the specimen showed multiple gray-white, soft to firm fragments, measuring 3.5 × 3 × 2.5 cm in largest dimension. Microscopic examination revealed a neoplasm of variable cellularity composed of plump and bland spindle cells arranged in sheets and fascicles, with focal whorl formations. Numerous psammomatoid structures were identified (Fig. 2a). Mitotic figures were not seen. Immunohistochemical studies using antibodies directed against epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) demonstrated weak expression in small groups of cells; antibodies directed against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) showed no immunoreactivity. The Ki-67 proliferative index was estimated to be 3%. This process was interpreted as a PM (WHO Grade I).

Fig. 2.

a Ossifying fibroma mimicking psammomatoid meningioma. Initial biopsy. (H&E, 100×) b Recurrent ossifying fibroma with psammomatoid pattern. (H&E, 200×) c Recurrent ossifying fibroma with trabecular pattern. (H&E, 100×) d Recurrent ossifying fibroma with trabecular pattern. (H&E, 200×)

Although the patient showed no neurological deficit and partial regression of the left proptosis, a six-month follow-up gadolinium contrast enhanced MRI of the brain demonstrated an enhancing extradural mass involving the left orbital roof, cribriform plate, ethmoid air cells, and nasal cavities. The left globe was displaced laterally with extension and disruption of the left medial lamina papyracea of the left orbit and left orbital apex narrowing. The tumor extended along the anterior left orbital roof intracranially along the cribriform plate, and across the midline with displacement laterally of the right medial orbital lamina papyracea.

A surgical re-excision was performed using a transnasal approach. The tumor consisted of multiple irregular tan-red rubbery soft tissue and bone fragments measuring in aggregate 7.0 × 5.0 × 2.0 cm. Histopathologically, numerous mineralized structures with a psammoma-like architecture were scattered throughout a cellular fibrous stroma (Fig. 2b). In addition, bone trabeculae with rimming osteoblasts were seen (Fig. 2c, d). The intertrabecular soft tissue component was characterized by plump spindle cells with no cytological atypia or mitotic figures. Immunohistochemical stains showed lack of expression for EMA, S100 and CD34. Ki67 index showed a low proliferation rate (3%). The findings were consistent with a juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF) with trabecular and psammomatoid features.

Slides from the previous surgical procedure were reviewed and compared. As juvenile psammomatoid ossifying fibroma (JPOF) and meningioma with psammoma bodies share similar histopathological features, tissue from the initial resection was sent for electron microscopy to confirm the cell lineage. No ultrastructural features suggestive of meningothelial cells were seen.

One year later, a subsequent MRI demonstrated tumor recurrence in the left frontal sinus, invading the left orbit. The cranial contents remained free of tumor. A left supraorbital mass resection was performed with histopathologic evidence of recurrent or residual JOF.

Discussion

The nomenclature and classification of juvenile active ossifying fibroma (JAOF) is considered controversial and has changed over the years [5]; JAOF is used to describe heterogeneous, benign fibro-osseous tumors of the craniofacial skeleton in young people. According to the WHO [1], JAOF may present as one of two histologic variants: juvenile psammomatoid ossifying fibroma (JPOF) and juvenile trabecular ossifying fibroma (JTOF). In 1985, Margo et al. [6] described the psammomatoid juvenile ossifying fibroma (JPOF) variant. Several other terms are used to identify tumors in this category, including juvenile active ossifying fibroma [7], juvenile ossifying fibroma with psammoma-like ossicles [8] and aggressive psammomatoid ossifying fibroma (APOF) [9]. The APOF has a locally aggressive behavior and a cellular stroma showing structures designated as ossicles, spherules and psammomatoid bodies, located in the paranasal sinuses (ethmoid and maxillary sinus) and supraorbital region (frontal and ethmoid bones) [6, 9, 10].

JAOF should not be confused with the central cemento-ossifying fibroma (CCOF), also known as central ossifying fibroma (COF). While most cases of CCOF arise in the jaws and thought to be of periodontal ligament origin [8, 11], similar lesions producing “cementum-like” material have been reported at distant extragnathic sites. JAOF is a locally aggressive neoplasm that tends to occur in the jaws or, less frequently, the craniofacial skeleton of young patients [12, 13]. In contrast, the classic CCOF is usually a well circumscribed lesion that develops in the jaws of adult patients, and most frequently in the mandible.

JPOF usually occurs in the orbital bones and paranasal sinuses, although it has also been reported in the maxilla, mandible, and other bones of the skull [7, 14]. JPOF has occurred in patients ranging in ages from 3 months to 72 years [7], while gradual enlargement has been reported. In the majority of cases, aggressive behavior has been documented in some patients. Radiographically, JPOF usually presents as an expansile and well-circumscribed radiolucent lesion surrounded by a thick wall [13, 15]. Histopathologically, JPOF is characterized by a proliferation of benign spindle shaped-fibroblastic cells with embedded mineralized structures. In some cases the mineralized tissue has the appearance of “ossicles,” characterized by round to ovoid collections of bone that have an osteoid rim. Intermingled psammoma-like calcifications may be seen that can fuse to form trabeculae. The stroma can vary from densely cellular to loose, with spindle cells showing indistinct cytoplasmic borders, multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells may be seen together with rare normal mitotic figures; however, atypia is not usually identified [1, 16]. Some studies have documented concurrent aneurysmal bone cyst or traumatic bone cyst formation with JPOF [7, 13, 14]. Recurrence is common (30%) as reported by Johnson et al., although malignant degeneration and metastases are not reported [12, 13].

JTOF occurs in young patients (2–33 years) [6]. It usually develops in the maxilla or mandible, and is characterized by rapid growth. Radiographically, JTOF presents as a well defined, unilocular or multilocular, expansile radiolucency with cortical thinning [14]. Histopathologically, JTOF is composed of a fibroblastic spindle cell stroma, containing osteoid matrix surrounded by osteoblasts and anastomosing trabeculae of immature woven bone [1]. Scattered clusters of benign multinucleated giant cells are often seen. Mitoses may be present, and cystic degeneration is rare [13, 17]. Recurrences are also documented in the JTOF [17]. Isolated case reports of JAOF are reported; however, the significance of this case presentation is the unique combination of both trabecular and psammomatoid patterns in the same tumor.

The clinical differential diagnosis of JOF includes fibrous dysplasia (FD). The growth of monostotic fibrous dysplasia usually tends to stabilize when skeletal maturity is attained [18]. Radiographically, FD is a poorly circumscribed bony expansion covered by a thin cortex that may appear radiolucent depending on the proportion of fibrous and osseous components, with various degrees of radiopacity, including a characteristic “ground glass” appearance on CT scanning [9]. Microscopically, FD consists of cellular fibrous tissue with spindle-shaped cells admixed with irregularly shaped trabeculae of woven bone with no osteoblastic rimming [19]. The radiographic and histopathologic characteristics are helpful in distinguishing between these two entities; however, lesions may show overlapping features [20].

JPOF may be difficult to distinguish from PM located in the craniofacial bones, as noted in the present case [11]. Primary extracranial meningiomas are rare and constitute 2% of all meningiomas. PM has been reported in the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx [2–4], arising from heterotopic rests of arachnoid cells (meningiocytes, meningothelial cells) [11]. Histopathologically, JPOF and PM may be difficult to distinguish at the time of intraoperative consultation (frozen sections), or even after obtaining routine H&E sections. Certain features favor PM rather that JPOF, including (1) the lack of associated osteoclasts and osteoblasts rimming the psammoma bodies [9], and (2) the haphazard distribution of psammoma bodies in PM. In contrast, the psammoma-like calcifications seen in JPOF are bony structures with osteoblast rimming and show a homogenous distribution [12]. PM usually show immunoreactivity for EMA and vimentin [2, 4]. Granados et al. reported EMA immunoreactivity in OF [11]; in addition it was shown that OF also express SMA and CD10 with lack of expression of CD34, S100 and cytokeratins [11, 21]. Most of meningiomas are immunoreactive for antibodies directed against S-100 protein; similarly, CD10 is expressed in a high percentage of PM; therefore, immunohistochemical stains may not be able to distinguish all cases and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of PM. In our case, the tumor was initially diagnosed as PM because of focal immunoreactivity for EMA. Examination of the previous slides and new sections revealed the presence of non-concentric and lamellar psammomatoid structures, and lack of EMA and S100 expression. The definitive diagnosis of JOF should be based on clinical and radiographic findings, in conjunction with the histopathologic characteristics of the lesions.

The treatment for JOF is complete excision of the tumor; partial resections are associated with recurrence due to the infiltrative nature of the tumor borders, although enucleation may not always be feasible, as in the present case. Furthermore, the specimen submitted to pathology is usually fragmented, precluding the appropriate evaluation of surgical margins. Cooperation among multiple specialists is necessary to define the extent of the disease, and its successful surgical excision may require a collaborative approach that includes neuroradiologists, neurosurgeons, ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists.

In summary, this paper presents a challenging and unique case of trabecular and psammomatoid JOF in a 15-year-old male mimicking PM. In this complex case, a multidisciplinary evaluation with careful assessment of clinical, radiographic and histopathologic features was necessary in order to arrive at the appropriate diagnosis and therapeutic approach.

References

- 1.Slootweg PJ, El-Mofty S. Ossifying fibroma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. pp. 319–320. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taxy JB. Meningioma of the paranasal sinuses. A report of two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:82–86. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199001000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson LD, Gyure KA. Extracranial sinonasal tract meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:640–650. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swain RE, Jr, Kingdom TT, DelGaudio JM, et al. Meningiomas of the paranasal sinuses. Am J Rhinol. 2001;15:27–30. doi: 10.2500/105065801781329419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz AA, Alencar VM, Figueiredo AR, et al. Ossifying fibroma: a rare cause of orbital inflammation. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:107–112. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181647cce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margo CE, Ragsdale BD, Perman KI, et al. Psammomatoid (juvenile) ossifying fibroma of the orbit. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:150–159. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson LC, Yousefi M, Vinh TN, et al. Juvenile active ossifying fibroma. Its nature, dynamics and origin. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1991;488:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slootweg PJ, Panders AK, Nikkels PG. Psammomatoid ossifying fibroma of the paranasal sinuses. An extragnathic variant of cemento-ossifying fibroma. Report of three cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1993;21:294–297. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wenig BM, Vinh TN, Smirniotopoulos JG, et al. Aggressive psammomatoid ossifying fibromas of the sinonasal region: a clinicopathologic study of a distinct group of fibro-osseous lesions. Cancer. 1995;76:1155–1165. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951001)76:7<1155::AID-CNCR2820760710>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhingra KK, Khurana N, Chatturvedi KU. Aggressive psammomatoid ossifying fibroma (APOF): two cases with short review. Pathology. 2008;40:418–420. doi: 10.1080/00313020802036756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granados R, Carrillo R, Najera L, et al. Psammomatoid ossifying fibromas: immunohistochemical analysis and differential diagnosis with psammomatous meningiomas of craniofacial bones. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noudel R, Chauvet E, Cahn V, et al. Transcranial resection of a large sinonasal juvenile psammomatoid ossifying fibroma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:1115–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-0867-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Mofty S. Psammomatoid and trabecular juvenile ossifying fibroma of the craniofacial skeleton: two distinct clinicopathologic entities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:296–304. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.121545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makek M. Clinical pathology and differential diagnosis of fibro-osseous lesions of the maxillofacial area–new aspects. Dtsch Z Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1986;10:212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han MH, Chang KH, Lee CH, et al. Sinonasal psammomatoid ossifying fibromas: CT and MR manifestations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman LA, Tabor MH, Mirani N. Pathologic quiz case: a sino-orbital mass in a 13-year-old adolescent girl. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e301–e302. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e301-PQCASO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slootweg PJ, Panders AK, Koopmans R, et al. Juvenile ossifying fibroma. An analysis of 33 cases with emphasis on histopathological aspects. J Oral Pathol Med. 1994;23:385–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1994.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toyosawa S, Yuki M, Kishino M, et al. Ossifying fibroma vs. fibrous dysplasia of the jaw: molecular and immunological characterization. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:389–396. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jundt G. Fibrous dysplasia. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. pp. 321–322. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voytek TM, Ro JY, Edeiken J, et al. Fibrous dysplasia and cemento-ossifying fibroma. A histologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:775–781. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams HK, Mangham C, Speight PM. Juvenile ossifying fibroma. An analysis of eight cases and a comparison with other fibro-osseous lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 2000;29:13–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]