Abstract

Objectives

Occupationally acquired infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an issue of increasing concern. However, the number of cases of occupational disease (OD) due to MRSA in healthcare workers (HCWs) and the characteristics of such cases have not been reported for Germany.

Methods

Cases of OD due to MRSA were identified from the database of a compensation board (BGW) for the years 2006 and 2007 and the individual files analyzed. The variables extracted from these data were occupation, workplace, workplace exposure, and the reasons for recognizing a claim as an OD. Seven cases were selected due to the specific characteristics of their medical history and described in more detail.

Results

Over a 2-year period, a total of 389 MRSA-related claims were reported to the BGW, of which 17 cases with infections were recognized as an OD. The reasons for not recognizing claims as an OD were either a lack of symptomatic infection or lack of a work-related MRSA exposure. The recognized cases were predominantly among staff in hospitals and nursing homes. The most frequent infection sites were ears, nose, and throat, followed by skin infections. Three cases exhibited secondary infection of the joints, associated with skin damage primarily caused by trauma. There was only one case in which a genetic link between an MRSA-infected index patient and MRSA in a HCW was documented. MRSA infections were recognized as an OD due to known contact with MRSA-positive patients or because workplace conditions were presumed to involve increased exposure to MRSA. Long-term incapacity resulted in four cases.

Conclusion

MRSA infection can cause severe health problems in HCWs that may lead to long-term incapacity. As recognition of HCW claims often depends on workplace characteristics, improved surveillance of MRSA infections in HCWs would facilitate the recognition of MRSA infections as an OD.

Keywords: MRSA, Occupational disease, Infection, Healthcare worker, Surveillance

Introduction

Nosocomial infections caused by methicillin-resistant (or multi-resistant) Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are on the increase (Boucher and Corey 2008; Gastmeier et al. 2008). The increased prevalence of MRSA in healthcare settings poses an increased risk of exposure to MRSA among healthcare workers (HCWs) (Albrich and Harbarth 2008). Various studies into the frequency of MRSA infection among medical and care personnel have been published reporting prevalence rates between 1 and 15% (Albrich and Harbarth 2008; Blok et al. 2003; Joos 2009; Kaminski et al. 2007; Scarnato et al. 2003). Due to different study designs, the prevalence rates were not comparable. Moreover, the studies were carried out during outbreaks and therefore did not represent prevalence data for staff in situations with endemic MRSA. As there are no recommendations in Germany for routine screening of HCWs (KRINKO 1999; Simon et al. 2009), there is only limited prevalence data on endemic MRSA in healthcare settings.

Under German law, infection due to workplace exposure may be recognized as an occupational disease (OD) and is subject to compensation if the relationship between occupational activity and disease is regarded as probable (Code of Social Law, SGB VII). Recognition of an occupationally acquired infection and hence the liability of an insurer with respect to OD requires evidence of an identifiable, plausible means of transmission, e.g. the identification of an index patient. In the event that an index patient cannot be found, it is still possible to grant recognition of an OD if the claimant’s area of employment poses an increased risk of infection, and comparable, non-occupational risks of infection are considered unlikely (presumed causality clause in SGB VII, Art. 9, Para. 3). This legislation regulation presupposes the existence of epidemiological data to assess workplace risk. In the event that the legal conditions are not fulfilled, the claim can be rejected by the insurer. As colonization with Staphylococci is a natural status (Kluytmans et al. 1997; Lowy 2009), it does not fulfil the prerequisite of the German legal conditions of an OD.

Until now, there has been little information available on the number of OD cases caused by MRSA and the characteristics of these cases. Therefore, the routine data of a compensation board for HCWs were analyzed for OD caused by MRSA, and the characteristics of these cases were described. Particular attention was given to the different reasons for recognition of MRSA infections as an OD among HCWs.

Methods

Claims submitted due to MRSA were selected for the years 2006 and 2007 from the data of the Berufsgenossenschaft für Gesundheitsdienst und Wohlfahrtspflege (BGW), the statutory accident insurance and prevention in the healthcare and welfare services. The analyses of the rejected MRSA claims were based on the routinely collected, computer-based data (age, sex, occupation, workplace, and exposure). For recognized MRSA claims, a more detailed analysis was performed. As these files were available in paper form only, all data had to be collected manually using a checklist to ascertain details on exposure, index patient, disease assessment, diagnostic findings, infected body sites, and the existence of competing, non-occupational risks of infection. The reasons given for recognition of claims of MRSA as an occupational infectious disease were collected from the experts’ appraisals of the respective case. Seven cases will be described in greater detail. These cases were chosen because of their particular medical history and because they provide special insight into the reasoning behind the adjudication procedure.

Basic descriptive statistics such as frequency were used to describe the study population. The files were selected in January 2009. The analysis was restricted to claims from 2006 to 2007 for two reasons: first, until January 2006, the data routinely collected by the BGW did not distinguish between MRSA infections and other infections, and second, a period of 12 months was allocated to recognized cases for the decision-making process.

Results

Between January 2006 and December 2007, a total of 389 suspected cases of OD due to MRSA were reported to the BGW. Following adjudication procedure of these cases, occupationally acquired MRSA infection was confirmed in 17 cases (4.4%), while 372 claims were rejected. Both groups of recognized and rejected cases were comparable in most characteristics (aged around 40, predominantly women, and most frequently working in nursing homes and hospitals), but they differed in their occupations (Table 1). More than 60% of the recognized cases were nurses or nursing assistants, almost double the number of rejected cases in that group. Geriatric nurses were the second most frequent occupation in both groups. Some occupations, such as medical and physician assistants, were only represented in the group of rejected cases. About 15% of the rejected cases were notified by employees not working in health-associated professions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the compensation claims for occupational disease due to MRSA reported to the Berufsgenossenschaft für Gesundheitsdienst und Wohlfahrtspflege in 2006 and 2007 separated by recognized and rejected cases

| Characteristics | Recognized cases n = 17 | Rejected cases n = 372 |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 44 (11.8) | 39 (11.3) |

| Gender, women | 16 (94) | 315 (85) |

| Occupation | ||

| Nurse, nurse aide | 11 (64) | 142 (38) |

| Geriatric nurse | 4 (24) | 93 (24) |

| Medical and physician assistant | 0 | 44 (12) |

| Medical doctor | 1 (6) | 34 (9) |

| Disability support worker | 1 (6) | 4 (1) |

| Othera | 0 | 55 (15) |

| Workplace | ||

| Nursing home for the elderly | 8 (47) | 125 (34) |

| Hospital | 6 (35) | 111 (30) |

| Outpatient care | 2 (12) | 71 (19) |

| Medical practice | 0 | 47 (13) |

| Facility for the disabled | 1 (6) | 9 (2) |

| Other | 0 | 9 (2) |

| Exposure at the workplace to MRSA | 17 (100) | 58 (16) |

| Diagnosis of MRSA | ||

| Staff screening | 2 (12) | ./.b |

| Medical examination prompted by symptoms of infection | 15 (88) | ./.b |

| Body sites infected by MRSA (multiple answers possible) | ./.b | |

| Ear, nose, throat, sinus ethmoidales | 9 (53) | |

| Skin | 7 (41) | |

| Bone (nasal septum, dental) | 3 (18) | |

| Joints (shoulder, DIP and PIP joints) | 3 (18) | |

| Respiratory tract (lung, bronchia) | 2 (11) | |

aIncludes occupations like administrative associated professions, housekeepers, cleaners

bData not collected or unknown

Among the recognized cases, two HCWs were diagnosed during routine screening and 15 by the attending physician whom they consulted due to their symptoms. The most frequently infected body sites were the ear, nose, throat, and skin (Table 1). More than half of the recognized cases were working in close contact with patients (Table 2). Although all 17 cases were recognized as an OD, in five cases, additional non-occupational risks of infection were found. In three of these cases, secondary joint infections were associated with skin damage, primarily caused by trauma during private activities. In eight cases, recognition as an OD was based on known contact to an index patient (Table 2). In one of these eight cases, a genetic link was confirmed with MRSA in the index patient, whereas for the other seven cases, MRSA carriage of the index patient was confirmed by a swab culture. In another case, MRSA carriage of an index patient was suspected but not confirmed by a swab culture. Five cases were recognized as an OD because increased MRSA prevalence in the patients treated in these care settings was presumed. In another three cases, MRSA infection was recognized as an OD without an expert appraisal.

Table 2.

Criteria collected in the assessment procedure and experts’ appraisal of claims for the recognition of MRSA infections as an occupational disease (n = 17)

| Criteria | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Occupational activities involving close contact with patients | 10 (59) |

| Additional, non-occupational risks of infection | 5 (29) |

| Confirmation of MRSA infection in the affected employee by swabbing cultures taken out of the infected wound(s) | 17 (100) |

| Reasons for recognition as an occupational disease | |

| Genetic link between MRSA of index patient and case | 1 (6) |

| Contact with an MRSA-positive patient confirmed by culture | 7 (41) |

| Contact with an MRSA-positive patient, no confirmation by culture available | 1 (6) |

| Workplace with presumed increased exposure to MRSA | 5 (29) |

| No expert appraisala | 3 (18) |

aPresumption of a workplace with increased MRSA rates (n = 1); Presumption of contacts with MRSA-positive patients without cultural confirmation (n = 2)

Among the rejected cases (n = 372), it was deemed that there were no reasons to suspect OD, which were presumably cases of MRSA colonization. Of the rejected claims, workplace exposure was not present in 84% of them while workplace exposure was given in 16%, but a causal link between workplace exposure and the MRSA disease was not deemed probable.

Case studies

Case 1

A 35-year-old nurse employed in outpatient care who was responsible for the care of two patients with chronic wounds and indwelling urinary catheters. MRSA infection had not been identified at the time of treatment. Due to very hot conditions, the HCW wore open-toed sandals. While emptying the catheter bag, some urine dripped onto her foot. A short time later, she noticed a slightly reddened area on the second toe of her right foot. She initially thought this was due to a yeast infection and treated it accordingly. The site developed into a phlegmon with severe blistering on her forefoot. Inpatient treatment was required, during which bacteriological tests detected an MRSA infection of the forefoot. MRSA infection of the index patient was proven by a positive MRSA culture of urine 1 month after MRSA infection had been detected in the nurse.

Case 2

A 52-year-old geriatric nurse working in a nursing home. Her work involved frequent contacts with an MRSA-positive patient. Following a fall, the nurse experienced a hot, painful swelling in her right shoulder. Despite treatment with antibiotics at home the symptoms worsened to the extent that emergency hospitalization became necessary 3 weeks later. In view of a suspected infection of the shoulder joint, arthroscopy was performed. This revealed generalized synovialitis, as well as a build-up of fluid and fibrous mass in the joint. Inflammatory changes to the bicep tendons and rotator cuff were observed. Post-operative bacteriological testing of samples proved positive for MRSA. Following synovectomy and debridement, intra-articular rinsing was carried out and a regime of topical and systemic antibiotic and cortisone therapy commenced. One year later, the patient still exhibited severe loss of movement in her right shoulder, as well as a depressive anxiety disorder. During the period of observation it was not possible for her to resume work.

Case 3

A 45-year-old doctor working on a cardiac surgery ward. She changed Vacu-Seal dressings on an MRSA-positive patient with a secondary, healing wound to the sternum. While holidaying in southern Europe, the doctor had dental treatment due to a root canal abscess. This condition improved after treatment with antibiotics, but the oral mucosa was still affected. On returning from her holiday, the doctor again worked in the ICU, but due to the persistence of the symptoms (damage to the oral mucosa), swabs were taken by the clinic’s staff physician, which revealed pharyngeal and oral colonization with MRSA. The infection progressed to various sites (inflammation of the eyes, swelling and blistering of the oral mucosa, swollen lymph glands in the groin, formation of several furuncles over the entire body) and was treated with repeated doses of antibiotics, which eventually led to a severe allergic reaction to antibiotics. The doctor was certified as unfit for work for a period of about 1 year and exhibited a persistent therapy-resistant MRSA colonization of the nose and throat with clinical symptoms. During the period of observation, it was not possible for her to resume work.

Case 4

A 51-year-old female disability support worker employed in a home for children with mental disability where MRSA infections were common among the young residents (one child had died of MRSA sepsis). An examination initiated by the disability support worker and carried out by her own general practitioner produced an MRSA-positive nasal swab. Following successful MRSA decolonization, she returned to her workplace. Three months later, routine screening of the children again revealed the presence of MRSA. Having tested positive again (presence of MRSA in the nose and throat), the disability support worker then received treatment with antibiotics. A week after treatment had been completed, she showed symptoms of sinusitis, accompanied by coughing, coughing attacks, and an irritable, persistent cough. Sinubronchitis due to MRSA was diagnosed, which then developed into pulmonary bronchitis. A year later, COPD had developed. The disability support worker was unable to continue in her work and left her profession.

Case 5

A 59-year-old nursing assistant employed in a nursing home for the elderly worked with three patients who were all known to be infected with MRSA. According to the HCW, the home personnel received no workplace instruction on how to deal with MRSA-infected patients, and there was inadequate provision of personal protective clothing and equipment for use when exposed to MRSA patients. While working in her garden at home, a paving stone fell on her right middle finger. One week later, she experienced swelling and pain throughout the entire middle finger. She presented as an outpatient for a surgical incision of the wound, which was swabbed. A bacteriological culture showed the presence of MRSA. Three weeks later, she developed another massive swelling on her finger with granular inflammation of the surgical wound. The patient was hospitalized due to a panaritium articulate condition that required surgery. Once the infection cleared, the patient was unable to completely form a fist. She experienced continued pain in the palm of her hand, and flexion of the distal interphalangeal joint was limited to 50°. In this case, an assessment to determine pension entitlement was initiated.

Case 6

A 54-year-old geriatric nursing assistant who worked permanent night shifts in a nursing home for the elderly and cared for a patient infected with MRSA. The HCW had a 17-year history of respiratory problems, such as attacks of breathlessness (including night-time attacks). Shortly after returning to her workplace from a holiday (during which she experienced no health problems), she fell sick with a feverish infection that was treated with antibiotics, which briefly improved her condition. One week later, the infection was exacerbated. MRSA was identified in her sputum. MRSA strains were characterized molecularly and showed an identical type to a patient treated in the nursing home around the time that the infection was potentially transmitted. Antibiotic susceptibility testing showed resistance to many commonly available antibiotics (e.g. penicillin, cephalosporin, carbapenem, doxycycline, macrolide, quinolone). The HCW was treated in hospital. She developed Gold 2 COPD with severe respiratory partial insufficiency on exertion. Treatment in hospital included combined antibiotic therapy, to which the condition did not respond satisfactorily. In the period observed, the HCW did not return to work. Due to the severity of her condition (dyspnea at rest), she was eventually registered as 70% disabled.

Case 7

A 44-year-old geriatric nurse working in an intensive care unit for patients with serious cerebral trauma had frequent contact with MRSA-infected patients (identified by routine screening). The HCW had suffered for several years from circulatory disorders and chronic inflammation of the middle ear. On two occasions, the HCW produced positive nasal swabs during routine screening of staff. Decolonization of MRSA was successful, but 1 month later during an ENT medical examination due to drum perforation, MRSA was found in secretions from the ear. Following several months of antibiotic treatment of a middle ear infection, tympanoplasy was performed. Hearing in the left ear remains impaired.

Discussion

Although a few reports on MRSA infection in HCWs have been published (Albrich and Harbarth 2008; Allen et al. 1997; Downey et al. 2005; Muder et al. 1993), there have apparently been none on MRSA infection as an occupational disease in HCWs regarding the relevance to liability under German law.

The frequency of MRSA infections has generally increased in hospital-associated settings as well as in the community (Boucher and Corey 2008; Grundmann et al. 2006; Health Council of the Netherlands 2007). Various surveys have systematically collected data on the prevalence of MRSA in patients in hospitals, particularly in intensive care units. These include EARSS, the European anti-microbial resistance surveillance survey (Tiemersma et al. 2004), and KISS, the German national nosocomial infection surveillance system (Gastmeier et al. 2008). However, the quality of the data collected on the prevalence of MRSA is not the same across all sectors of healthcare (Woltering et al. 2008). For example, prevalence rates of MRSA in nursing homes are mere estimates (Baldwin et al. 2009), while data on facilities for the disabled either do not exist at this time or are unavailable. Due to the increased prevalence of MRSA in healthcare settings, a higher risk is assumed for HCWs (Albrich and Harbarth 2008). About 389 HCWs had submitted occupational-related MRSA claims to the BGW during a 2-year period, of which 4.4% were recognized as OD. The employees were working predominantly in nursing homes and hospitals—mainly engaged in nursing activities. Our paper presents 17 cases of MRSA infections recognized as an OD in HCWs who had worked in different settings within the healthcare system.

Medical history and pathogenesis of infection

Infections of the ear, nose, and throat were the most frequent followed by infections of the skin. However, a recent review of the role of HCWs in MRSA transmission contradicted these findings, placing skin or soft tissue infections at the top of the list (71%) (Albrich and Harbarth 2008). In two cases from our sample, the infection spreads from the upper to the lower respiratory tract, causing complications such as bronchitis, pneumonia, and consecutive COPD. Other sites of MRSA infection were bones and joints. These sites are not mentioned by Albrich and Harbarth (Albrich and Harbarth 2008), although bones and joints are known to offer favorable conditions for the hematogenous spread of infection (Lowy 2009). Three cases from our sample presented secondary joint infections associated with skin damage, primarily caused by trauma. These endogenous infections could be due to MRSA colonization (Kluytmans et al. 1997; Söderquist and Hedström 1986). It is assumed that rates of MRSA carriage are higher among HCWs than in the broader community (Kluytmans et al. 1997). For this reason, trauma-related bone and joint infections are recognized as an OD in HCWs, despite the fact that in some cases, the initial accident or injury that triggered the infection occurred in a domestic setting.

Recognition of an MRSA infection as an occupational disease

For an MRSA infection to be recognized as an OD, the carrier status of the employee(s) and the index patient must be determined. In most instances, the question as to whether MRSA disease in a HCW was work-related or not has to be answered retrospectively. Obviously, it would be easier to identify the infectious pathway if the time of MRSA colonization could be ascertained more precisely. This would be feasible if staff were routinely screened. However, German guidelines on the prevention of MRSA transmission (KRINKO 1999; Simon et al. 2009), in common with national and international practice, do not recommend routine screening of HCWs (Albrich and Harbarth 2008; Dietlein et al. 2002). Nonetheless, two cases of MRSA carriage in our sample were detected during screening. In order to identify an index patient, it would be helpful if risk patients were routinely swabbed upon admission. As the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient screening are unproven and the quality of the evidence is poor (McGinigle et al. 2008), other deciding criteria should be established for the appraisal of MRSA infection as an OD in HCWs.

The practice under German law is to apply the presumed causality clause in order to facilitate the recognition of OD claims in those cases where no index patient has been identified, but the infection appears to be evidently occupationally related (SGB VII, Art. 9, Para. 3). In all 17 recognized cases, it was assumed that the infected HCW had been in direct contact with patients likely to have proven MRSA-positive, although this could be verified in only 53% of these cases. It is apparent that the quality of evidence substantiating workplace-related infection varies. These figures show that conclusive evidence of a causal link between MRSA infection and the workplace, i.e. recorded exposure to MRSA-positive patients, was determined only in every second HCW.

The procedure to adjudicate claims for recognition of MRSA infection as an OD involved both hard facts and less conclusive evidence. The strongest argument for a causal relationship was a similar genetic profile of the index patient and the HCW. The least conclusive argument was the presumption that the workplace was a healthcare setting in which MRSA was endemic. In 18% of the recognized cases, no expert appraisal was performed. This may be because many MRSA cases recovered without complications and incurred low medical costs so that an expert appraisal was deemed unwarranted.

The reasons for rejecting claims for the recognition of MRSA as an OD were not analyzed in this paper. The data in the standard documentation of rejected cases are not detailed enough to allow reliable assessment, with regard to exposure and symptoms. Furthermore, the data do not distinguish between colonization and infection. The data suggest that a large proportion of the MRSA claims were rejected by the BGW because MRSA colonization is not considered legitimate confirmation of OD. A large proportion of the rejected claims for which no specific workplace exposure was established were probably reported for prophylactic reasons to allow for the possibility that it should prove necessary to make an insurance claim.

The German Code of Social Law (SGB VII, Art. 9, Para. 3) stipulates that sufficient probability of a workplace-related cause of disease should be established. Additional, non-occupational risks of infection were found in five cases. However, the assessors did not address risks outside the HCW’s job in their appraisal of these cases. Presumably, the assessors considered the risk of infection among HCWs to be higher than the endemic risk in the population at large. Nevertheless, this illustrates that it is often difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish between occupational and non-occupational risks of infectious diseases (Haufs and Merget 2007). This is particularly problematic when non-occupational risks relevant to occupational MRSA are considered, e.g. nosocomial infections acquired by the HCW during hospitalization or surgical procedures (Downey et al. 2005), MRSA infections by a family member (Allen et al. 1997), or having been in contact with healthcare in high prevalence regions. The few studies that have considered the risk of hospital-acquired infections among HCWs do not provide any insight into the specific circumstances of exposure, i.e. whether the HCW might have been an inpatient or outpatient at the time the infection was transmitted (Albrich and Harbarth 2008).

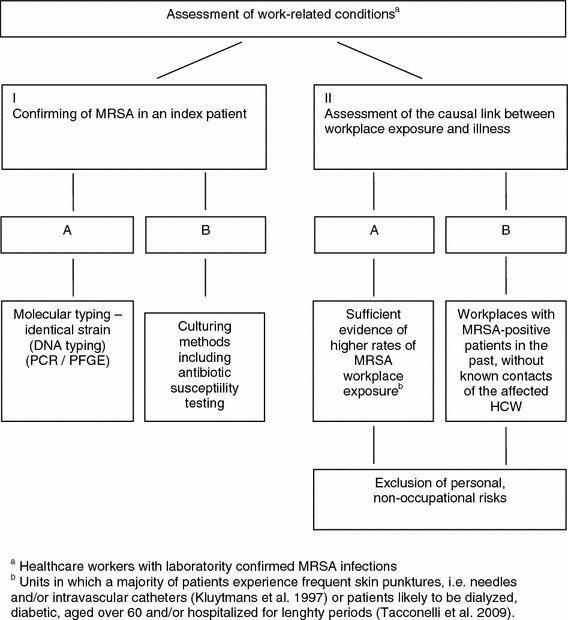

Using different exposure categories will facilitate the adjudication procedure of MRSA infection as an OD. In cases of MRSA infections in HCWs, when there is a known index person (Fig. 1, category IA or IB) and a non-occupational risk is not apparent, the infection can be considered to be occupationally acquired. By contrast, where cases are based on epidemiological data (solely empirical decision making), non-occupational risks should be assessed thoroughly (Fig. 1, category IIA or IIB). In these cases, an assessment of exposure would be based on the findings of epidemiological studies examining the endemic occurrence of MRSA in that particular care setting. Currently, there is insufficient good-quality evidence to substantiate the existence of a permanent increased exposure to MRSA in all areas of healthcare. On the contrary, specific groups of patients who present consistently higher rates of MRSA (Fig. 1, category IIA) pose a greater risk to HCWs (Kluytmans et al. 1997; Tacconelli et al. 2009). In general, there should be an individual assessment of non-occupational risks when contact between an affected HCW and an MRSA-positive patient cannot be proven (Fig. 1, category IIB).

Fig. 1.

Exposure categories for the adjudication procedure of occupationally acquired MRSA infections in healthcare workers (HCWs)

This paper outlines the risk of substantial health problems facing HCWs with MRSA infections. Due to the increasing resistance of S. aureus and the growing difficulties in finding effective treatment, it is imperative that measures are taken to minimize the risk of infection to HCWs.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Albrich WC, Harbarth S. Health-care workers: source, vector, or victim of MRSA? Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:289–301. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KD, Anson JJ, Parsons LA, Frost NG. Staff carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (EMRSA 15) and the home environment: a case report. J Hosp Infect. 1997;35:307–311. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(97)90225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin NS, Gilpin DF, Hughes CM, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in residents and staff in nursing homes in Northern Ireland. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:620–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blok HE, Troelstra A, Kamp-Hopmans TE, et al. Role of healthcare workers in outbreaks of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a 10-year evaluation from a Dutch university hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:679–685. doi: 10.1086/502275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher HW, Corey GR (2008) Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 46 Suppl 5:S344–S349 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dietlein E, Hornei B, Krizek L, Hengesbach B, Exner M. Recommendations for MRSA control: in homes for the elderly, nursing homes and rehabilitation clinics—a contribution to discussion. Hyg Med. 2002;27:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Downey DG, Kidd TJ, Coulter C, Bell SC. MRSA eradication in a health care worker with cystic fibrosis; re-emergence or re-infection? J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4:205–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastmeier P, Sohr D, Schwab F et al. (2008) Ten years of KISS: the most important requirements for success. J Hosp Infect 70 Suppl 1:11–16 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grundmann H, Aires-de-Sousa M, Boyce J, Tiemersma E. Emergence and resurgence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a public-health threat. Lancet. 2006;368:874–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haufs MG, Merget R. Begutachtung infektionsbedingter Krankheiten—Möglichkeit einer außerberuflichen Ursache kann Bewertung erschweren. BGFA-Info. 2007;1:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Health Council of the Netherlands (2007) MRSA policy in the Netherlands. Publication number: 2006/17E. edited by Health Council of the Netherlands (eds.) The Hague (NL)

- Joos AK. Screening of staff for MRSA in a university hospital department of surgery. Hyg Med. 2009;34:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski A, Kammler J, Wick M, Muhr G, Kutscha-Lissberg F. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among hospital staff in a German trauma centre: a problem without a current solution? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:642–645. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B5.18756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505–520. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRINKO (1999) Empfehlung zur Prävention und Kontrolle von Methicillin-resistenten Staphylococcus-aureus-Stämmen (MRSA) in Krankenhäusern und anderen medizinischen Einrichtungen—Mitteilung der Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention am Robert-Koch-Institut. Bundesgesungheitsbl Gesunndheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 42:954–958

- Lowy FD. Infektionen durch Staphylokokken. In: Dietel M, Suttrop N, Zeitz M, editors. Harrisons Innere Medizin—Band 1. Berlin: ABW Wirtschaftsverlag; 2009. pp. 1086–1096. [Google Scholar]

- McGinigle KL, Gourlay ML, Buchanan IB. The use of active surveillance cultures in adult intensive care units to reduce methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-related morbidity, mortality, and costs: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1717–1725. doi: 10.1086/587901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muder RR, Brennen C, Goetz AM. Infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among hospital employees. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993;14:576–578. doi: 10.1086/646640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarnato F, Mallaret MR, Croize J, et al. Incidence and prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage among healthcare workers in geriatric departments: relevance to preventive measures. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:456–458. doi: 10.1086/502232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A, Exner M, Kramer A, Engelhart S. Umsetzung der MRSA-Empfehlung der KRINKO von 1999—Aktuelle Hinweise des Vorstandes der DGHK. Hyg Med. 2009;34:90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Söderquist B, Hedström SA. Predisposing factors, bacteriology and antibiotic therapy in 35 cases of septic bursitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1986;18:305–311. doi: 10.3109/00365548609032341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli E, De AG, Cataldo MA, et al. Antibiotic usage and risk of colonization and infection with antibiotic-resistant bacteria: a hospital population-based study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4264–4269. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00431-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemersma EW, Bronzwaer SL, Lyytikäinen O, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe, 1999–2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1627–1634. doi: 10.3201/eid1009.040069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltering R, Hoffmann G, Daniels-Haardt I, Gastmeier P, Chaberny IF. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients in long-term care in hospitals, rehabilitation centers and nursing homes of a rural district in Germany. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:999–1003. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1075683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]