Abstract

Unlike conventional αβ T cells, which preferentially reside in secondary lymphoid organs for adaptive immune responses, various subsets of un-conventional T cells, such as the γδ T cells with innate properties, preferentially reside in epithelial tissues as the first line of defence. However, mechanisms underlying their tissue-specific development are not well understood. We herein report that among different thymic T cell subsets fetal thymic precursors of the prototypic skin intraepithelial Vγ3+ T lymphocytes (sIEL) were selected to display a unique pattern of homing molecules, including a high level of CCR10 expression that was important for their development into sIELs. In fetal CCR10 knockout mice, the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors developed normally in the thymus, but were defective in migrating into the skin. While the earlier defect in the skin-seeding by sIEL precursors was partially compensated for by their normal expansion in the skin of adult CCR10 knockout mice, the Vγ3+ sIELs displayed the abnormal morphology and increasingly accumulated in the dermal region of skin. These findings provide the definite evidence that CCR10 is important in the sIEL development by regulating the migration of sIEL precursors and their maintenance in proper regions of the skin and support the notion that unique homing properties of different thymic T cell subsets plays an important role in their peripheral location.

Introduction

Unlike conventional αβ T cells, which preferentially reside in secondary lymphoid organs for adaptive immune responses, various subsets of un-conventional T cells, such as the γδ T cells with innate properties, preferentially reside in epithelial tissues covering the external and internal surface of the body, including the skin, reproductive tracts, lungs, and intestines where they function as the first line of defense (1).

The γδ T cells of the different epithelial tissues use different γδ TCRs and originate from thymi of specific ontogenic stages (2). In mice, skin intraepithelial γδ T lymphocytes (sIEL, also referred to as dendritic epidermal T cells or DETC) express canonical Vγ3/Vδ1+ γδTCRs and their precursors are generated only in early fetal thymi. Vγ4+ cells of later fetal thymi contribute as the dominant γδ T cell population in other epithelial tissues such as the reproductive tract, tongue, and nasal mucosa (2, 3). On the other hand, γδ T cells located in the secondary lymphoid organs (SLO) are preferentially Vγ2 or Vγ1.1+ and originate from the adult thymus. While it is well established that the waved generation of γδ T cell subsets is primarily due to the genomically programmed rearrangement of specific Vγ genes at different ontogenic stages (4), mechanisms regulating their tissue-specific development are poorly understood.

Recent studies found that a selection process is involved in the tissue-specific development of Vγ3+ sIELs, the dominant epidermal T cell population in mice. The Vγ3+ sIELs play an important role in protection of the skin through various functions such as immune surveillance against tumours (5), regulation of local inflammatory responses (6), and promotion of wound healing (7). In genetically modified mice whose production of the Vγ3+ γδ T cells is impaired in the fetal thymus, the Vγ3+ γδ T cells are still the dominant subset of sIELs in adults, suggesting that the Vγ3+ cells are selected over other T cell subsets to develop into sIELs (8). In absence of the native Vγ3/Vδ1+ sIELs, such as in Vγ3 or Vδ1 knockout mice, other γδ T cell subsets could substitute in the skin. However, the substitute sIELs have a restricted TCR configuration (9-11). In TCRδ6.3 transgenic mice, transgenic sIELs were absent unless an endogenously encoded TCRδ chain, preferentially TCRδ1, was co-expressed (11), supporting the involvement of selection.

The selection process for sIEL development starts within the fetal thymus. We first reported that fetal thymic γδ T cell populations that display activated or memory phenotypes correlated with their development into sIELs (12). In wild type mice, the fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors are a predominant population that displays the activated phenotypes, including the upregulation of CD122 (IL-15 receptor β, IL-15Rβ), suggesting that they are selected. In a sub-strain of FVB mice (Taconic) that bears the mutated Skint1 molecule, a selecting ligand for the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors, the Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδ T cells remain at an immature status and could not develop into sIELs efficiently (13, 14), confirming that the positive selection is critical for the development of sIELs. Furthermore, a subset of transgenic fetal thymic γδ T cells could develop into sIELs if they are positively selected as the Vγ3+ cells (12)(15).

The positive selection of fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors might endow them with a unique homing property to migrate in the skin. Compared to un-selected fetal thymic γδ T cells, the positively selected Vγ3+ sIEL precursors had a coordinate switch in the expression of multiple homing molecules, including the upregulation of CCR10 (G protein-coupled receptor-2, GPR-2), sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1), and the downregulation of CCR6, which might be important for their peripheral location (12). S1PR1 is known to be critical for thymus-exiting of mature T cells (16). On the other hand, considering the high level expression of chemokine CCL27, a ligand for CCR10, in the skin (17), CCR10 may serve as a skin-homing receptor for positively selected Vγ3+ cells. However, a recent publication found no apparent sIEL defect in adult CCR10-knockout mice, leaving the role of CCR10 in the sIEL development unclear (18).

Using a newly generated strain of CCR10-knockout mice with a knocked-in EGFP as a reporter for CCR10, we systemically analyzed the regulation of CCR10 expression in cells at different stages of the sIEL development and its role in the sIEL development. We report herein that CCR10 is involved in multiple aspects of the sIEL development.

Materials and Methods

Generation of CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice

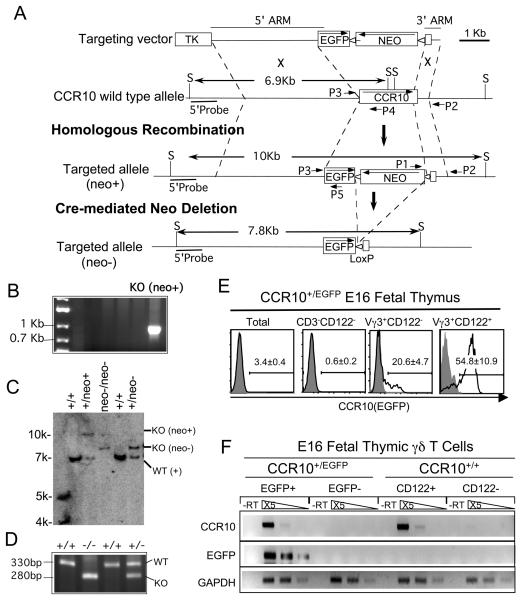

CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice were generated as outlined in the Figure 1. First, a targeting construct was assembled which includes a 3.6Kb DNA fragment exactly 5′ of the start codon of the CCR10 gene (5′ arm), followed by a coding sequence for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), a loxP flanked Neo gene cassette, and a 0.5Kb DNA fragment consisting of a 0.2Kb 3′ portion of CCR10 coding region and a 0.3Kb 3′ non-coding region (3′ arm). The 3.6Kb 5′ and 0.5Kb 3′ arms were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA of 129 svJ mice and confirmed by sequencing. The linearized targeting construct was then transfected into mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells (the J1 line) (19), of which the G418/gancyclovir-resistent clones were screened for knockout recombinants by genomic PCR with a primer set that amplifies a 0.9 Kb band from the 3′ end of the targeted CCR10 allele (Fig. 1A and B). The knockout clones were further confirmed by a Southern blot with a probe specific for a region 5′ upstream of the targeted region (Fig. 1A and C). The targeted allele (neo+) deletes a 1.7Kb DNA fragment coding for N-terminal extra-cellular and all of the seven trans-membrane domains of the CCR10 gene and replaces it with an EGFP coding sequence and a loxP-flanked Neo cassette. The neo+ CCR10 knockout clones were microinjected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 (B6) mice to generate chimera mice. The male chimera mice were crossed with female EIIa-Cre transgenic mice to delete the loxP-flanked Neo gene cassette from the CCR10 targeted allele to generate heterozygous CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice (CCR10+/EGFP) (Fig. 1A and C). The CCR10+/EGFP mice were backcrossed to wild type B6 mice for 8-9 generations and inter-crossed to generate homozygous CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin (CCR10EGFP/EGFP) mice. B6 and transgenic EIIa-Cre mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All animal experiments were approved by Pennsylvania State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Figure 1.

Generation of CCR10-knockout mice with a knocked-in EGFP reporter. A. Targeting and screening strategies for generation of CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice. B. The screening for CCR10 knockout ES cell clones by a genomic PCR with primers P1 and P2 (the Panel A) that would amplify a 0.8Kb band from the CCR10 knockout allele but not wild type CCR10 allele or CCR10 knockout construct inserted into the genome. C. Southern blot analysis of CCR10 knockout ES cells or mice. Genomic DNAs of the cells and mice were digested with restriction enzyme Sac I (S) and probed with a 0.8Kb DNA fragment located 5′ upstream of the 5′ arm in the CCR10 allele (5′Probe, panel A). The Southern blot gave bands of 6.9, 7.9 and 10 Kb sizes of the wild-type, neo+ CCR10 targeted allele (neo+) and neo-deleted targeted CCR10 allele (neo−) respectively. +/+: wild type ES cells and mice; neo+: recombinant CCR10 knockout ES cells with the neo cassette; neo−/neo−: homozygous CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice with the neo cassette deleted; +/neo−: heterozygous CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice with the neo cassette deleted. D. Identification of heterozygous and homozygous CCR10 knockout mice by a genomic PCR with primers P3, P4 and P5 (panel A), which amplifies a 330bp wild-type and a 280bp knockout band. E. Flow cytometric (FACS) analysis of EGFP expression in fetal thymic Vγ3+ γδ T cells before and after the positive selection. Thirty-one CCR10+/EGFP fetuses were analyzed. F. Correlated expression of the knocked-in EGFP and endogenous CCR10 genes. Different fetal thymic Vγ3+ cell populations were purified from CCR10+/EGFP and CCR10+/+ mice based on their EGFP or CD122 expression (as indicated) by cell-sorters. Levels of CCR10 and EGFP transcripts in the sorted populations were analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. -RT, no reverse transcription. GAPDH was used as loading controls. N=2.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-CD3, CD122, CD62L and γδTCR antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA); anti-CD24, CCR7 and αE from BioLegend (San Diego, CA); anti-Vγ2, Vγ3, β7 and α4β7 from BD Bioscience (San Diego, CA); and anti-CCR9 from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). 17D1 antibody was previously described (9). CCL27 was purchased from Pepro Tech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Cell preparation

Thymocytes were isolated from mice as described (12). To isolate lymphocytes from epidermal and dermal regions, the dorsal and ventral skin was treated with 20mM EDTA to be separated into the epidermis and dermis. The epidermis was minced and digested with a 0.3% Trypsin solution for 20 minutes at 37°C to dissociate the cells (20). The dermis was minced and digested with collagenase for 1-2 hours with gentle shaking to dissociate the cells (21). Mononucleocytes were enriched from the cell preparations using Percoll gradients (40%/80%) and then used for flow cytometric analysis.

Flow cytometry

Cells were incubated with fluorescently labelled antibodies for 30 min at 4°C (or room temperature for CCR7 staining) and analyzed on the flow cytometer FC500 (Beckman Counter, Miami, FL).

Cell sorting

E17 fetal thymocytes of CCR10+/EGFP mice were stained and sorted for EGFP+ and EGFP− Vγ3+ cells with an Influx sorter (Cytopeia, Inc. San Jose, CA). E17 fetal thymocytes of wild type mice were stained and sorted for CD122+ and CD122− Vγ3+ cells. Vγ3+ sIELs were purified by the sorter from epidermal cell preparations based on the Vγ3/CD3 expression. Purities of the sorted populations were at least 95%.

Immunofluorescent microscopy of epidermal sheets

The experiment was performed similarly as described (22). The epidermal sheets were peeled from the ear skin of adult mice or the back skin of 2-3 day-old newborns after the skins were incubated in a 20 mM EDTA/PBS solution for one hour. The sheets were fixed with acetone, and then stained with FITC-conjugated anti-γ3 antibodies (or biotin-conjugated anti-Vγ3 antibodies/streptavidin-Alexa 568) overnight and analyzed on a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX61 or Nikon Eclipse TE300).

Immunofluorescent microscopy of skin sections

Ten μm cryosections of the back skin were fixed in methanol for 30 min at −20°C and co-stained with Alexa 647-conjugated anti-CD3 and FITC-conjugated anti-Vγ3 antibodies in the Antibody Amplifier Eclipse (ProHisto, Columbia, SC) at 4°C overnight. The stained sections were covered with Vectashield mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and analyzed on an Olympus BX61 fluorescence microscope or an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc. Center Valley, PA).

In vitro chemotaxis assay

The experiment was performed as described (12). Briefly, 5× 105 E17 fetal thymocytes of wild type or CCR10 knockout mice suspended in DMEM/10% FBS were placed into the upper chamber of a Transwell plate containing 5 μm pore filters (Costar Corp.) and incubated with CCL27 (R&D Systems) or conditioned medium of E18 fetal skin in the bottom chamber for 4 hours. Cells migrating into the bottom chamber were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry for Vγ3+ γδT cells.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

The experiment was performed as previously described (12). Primer sequences are CCR7f: ctcggcaacgggctggtgatactg and CCR7r: cgtgtcctcgccgctgttcttctg for CCR7; CCR10-5′: agagctctgttacaaggctgatgtc and CCR10-3′: caggtggtacttcctagattccagc for CCR10; S1PR1-5′: gtacttcctggttctggctgtgc and S1PR1-3′: cgtttccagacgacataatgg for SIPRI. L3: ccagcagccactaaaatgtc and J1: cttaccagagggaattactatgag for TCRγ3; GAPDH-5′: ctgacgtgccgcctggagaaa and GAPDH-3′: tgttgggggccgagttgggatag for GAPDH; EGFP-5′: actacctgagcacccagtccgccctg and EGFP-3′: gctctagatttacttgtacagctcgt for EGFP. Primers for tubulin have been described (23).

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Statistical significance was determined by two-tail student T tests. P < 0.05 is considered significant.

Results

Generation of CCR10 knockout mice with a knocked-in EGFP as a reporter for the CCR10 expression

To study the role of CCR10 in sIEL development, we generated CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice. The CCR10 coding sequence was replaced with an EGFP coding sequence that serves as a reporter for CCR10 expression (Fig. 1A-D). The Neo gene cassette was removed from the targeted CCR10 allele by the Cre/LoxP-mediated deletion to get “clean” CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice because the Neo gene cassette, with its own strong promoter, interfered with the regulation of the knocked-in EGFP gene expression by the endogenous regulatory machinery (24).

The knocked-in EGFP in the CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin mice faithfully reports the expression of CCR10. Of the E17 fetal thymocytes of heterozygous CCR10+/EGFP mice, significantly higher percentages of the CD122+ Vγ3+ γδ T cells expressed much higher levels of EGFP than the CD122− Vγ3+ γδ T cells or earlier progenitors (Fig. 1E). This correlates with our previous findings that the positively selected Vγ3+ fetal thymic sIEL precursors had higher CCR10 transcripts than the un-selected γδ T cell population (12). Furthermore, in purified EGFP+ and EGFP− populations of the E17 fetal thymic Vγ3+ γδ T cells of the CCR10+/EGFP mice, levels of CCR10 and EGFP transcripts were correlated (Fig. 1F). The EGFP expression was also correlated with the CCR10 transcription between different thymic T cell and sIEL populations, as demonstrated in several experiments throughout this paper (see Fig. 2A-B and Fig. 5A-B for details). In addition, nearly all IgA+ cells, but few other cells, of the intestine had high EGFP signals (not shown), also correlating with previous findings (25). These results suggest that the knocked-in EGFP is a reliable reporter for the CCR10 expression and provide the first direct evidence that CCR10 is expressed on the majority of positively selected CD122+ Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδ T cells.

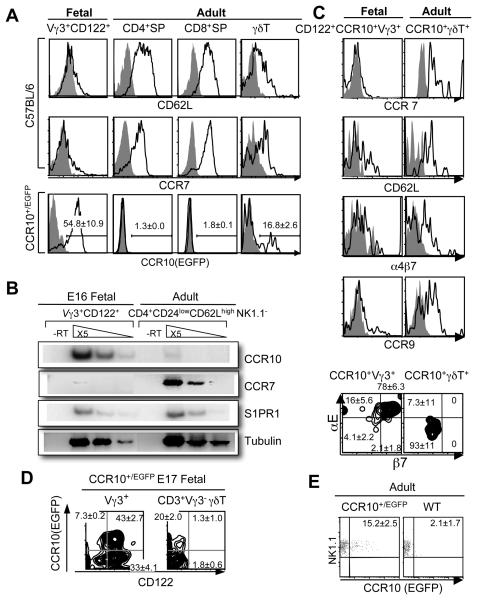

Figure 2.

Differential expression of CCR10 and other homing molecules among positively selected fetal thymic Vγ3+ and other thymic T cell subsets. A. FACS analysis of CCR10 (EGFP), CD62L, and CCR7 expression on positively selected E16 fetal thymic Vγ3+ (N=8) vs. adult (N=3) thymic CD4+, CD8+ or γδ T cells. The CCR10 (EGFP) analysis was on CCR10+/EGFP mice (N≥4). B. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR determination of CCR7, CCR10 and S1PR1 expression in mature E16 fetal thymic CD122+ Vγ3+ and adult thymic CD24lowCD62LhighNK1.1− CD4+ cells of C57BL/6 mice. The experiments were repeated twice. C. FACS analysis of α4β7, CCR9, CCR7, CD62L, αE and β7 expression on CCR10(EGFP)+ E16 fetal (N=10) thymic Vγ3+ vs. adult (N=2) thymic γδT cells. D. Comparison of CCR10 (EGFP) and CD122 expression on E16 fetal thymic Vγ3+ vs. Vγ3− γδT cells of CCR10+/EGFP mice. More than five mice were analyzed. E. Expression of CCR10 (EGFP) on the gated adult NK1.1+ CD3+ thymocytes. The experiments were repeated twice.

Figure 5.

Regulated CCR10 expression in sIELs and their thymic precursors. A. FACS analysis of CCR10 (EGFP) expression on the adult Vγ3+ sIELs and fetal thymic CD122+ Vγ3+ T cells of CCR10+/EGFP mice. B. Comparison of levels of CCR10 transcripts in adult sIELs and positively selected fetal thymic sIEL precursors. RNAs of purified adult Vγ3+ sIELs and E16 fetal thymic CD122+Vγ3+ cells of wild type mice were analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR for CCR10 transcripts. The experiments were repeated twice.

Unique patterns of expression of CCR10 and other homing molecules on different thymic T cell populations

Taking advantage of the knocked-in EGFP reporter, we analyzed the expression of CCR10 (EGFP) in the fetal thymic Vγ3+ and other thymic T cell subsets that are known to have different preferential peripheral locations. First, we compared the expression of CCR10 (EGFP) between the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors and conventional thymic CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells that preferentially localize in secondary lymphoid organs (SLO). In contrast to the fetal thymic CD122+ Vγ3+ cells, few conventional thymic αβ T cells expressed CCR10 (EGFP) (Fig. 2A). Instead, the conventional αβ T cells expressed higher levels of CCR7 and CD62L, molecules involved in their localization to SLOs (26, 27), than the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors (Fig. 2A). The differential expression of CCR10 vs. CCR7 between the positively selected CD122+ Vγ3+ and conventional CD4+ αβ T cell populations was further confirmed by the semi-quantitative RT-PCR, while both populations expressed similar levels of S1PR1 (Fig. 2B), a molecule involved in T cell egress from the thymus (16).

The majority of adult thymic γδT cells expressed similar patterns of homing molecules as the αβT cells (Figure 2A, right panels), consistent with their preferential location in SLOs. However, a small but notable portion of the adult thymic γδ T cells expressed CCR10 (EGFP) (Fig. 2A). But the CCR10 (EGFP)+ adult thymic γδ T cells displayed different expression profiles of many other homing molecules than the CCR10 (EGFP)+ Vγ3+ sIEL precursors that, apart from expressing low CD62L and CCR7, were also low in the expression of CCR9 and integrin α4β7, molecules involved in homing to the gut, and high in αEβ7, an integrin involved in epidermal localization of sIELs (Figure 2C) (28).

We also analyzed the expression of CCR10 (EGFP) on Vγ3− γδ T cells in fetal thymi of CCR10+/EGFP mice. Compared to the Vγ3+ fetal thymic cells, a smaller portion of the Vγ3− fetal thymic γδ T cells expressed lower levels of CCR10 (Fig. 2D). The CCR10 (EGFP)+ Vγ3− fetal thymic γδ T cells did not express CD122, indicating that they were not selected as the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors, and, like the CCR10 (EGFP)+ adult thymic γδ T cells, expressed other homing molecules differently than the CCR10+ Vγ3+ sIEL precursors (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A sizable portion of NK1.1+ adult thymic T cells also expressed CCR10 (EGFP), similar to the thymic γδ T cells (Fig. 2E). However, the CCR10 (EGFP)+ NK T cells were mainly αβ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting that they are a distinct population. Interestingly, the CCR10 (EGFP)+ NK T cells displayed an expression pattern of homing molecules that was more similar to those of the CCR10+ Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes than the other CCR10+ γδ T cells, including the high level of integrin αE but low in α4β7 expression (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Together, these data demonstrate that the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors and other thymic T cell populations express different patterns of homing molecules that might determine their specific peripheral localizations. Particularly, CCR10 (EGFP) is expressed on various thymic γδ T cell subsets known to localize preferentially into different epithelial tissues that abundantly express ligands for CCR10, including CCL27 and CCL28 (29, 30)(31), but not on the conventional αβ T cells that preferentially localize into SLOs. In addition, the expression of CCR10 (EGFP)+ on one NKT subset might be associated with their preferential localization in non-lymphoid peripheral tissues, including the skin (32). Most notably, the high level of CCR10 (EGFP) expression on the majority of positively selected Vγ3+ fetal thymic T cells suggests a potentially important role of CCR10 in their development into sIELs.

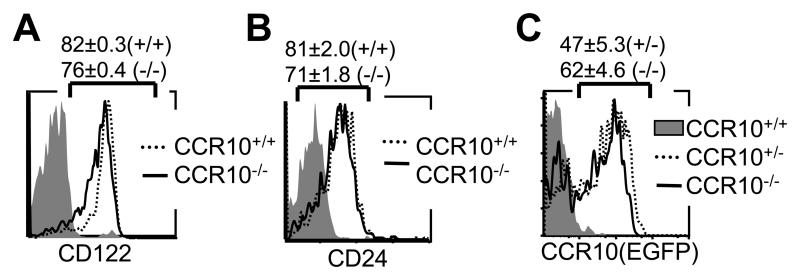

Normal developmental and selection processes of Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in fetal thymi of CCR10 knockout mice

To dissect the involvement of CCR10 in the sIEL development, we first analyzed the generation and selection of the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in fetal thymi of the CCR10 knockout mice. Compared to wild type littermates, homozygous CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice had essentially the same number of fetal thymic Vγ3+ cells that also expressed the positive selection and maturation markers CD122 and CD24 (Fig. 3A). In addition, there was only a slight, if any, difference in percentages of EGFP+ Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes between CCR10EGFP/EGFP and CCR10+/EGFP mice (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that CCR10 is not importantly involved in the intra-thymic development processes of Vγ3+ sIEL precursors or their egress from the thymus, which is likely mediated by different homing molecules such as S1PR1 (16).

Figure 3.

Normal development of Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in fetal thymi of CCR10 knockout mice. A and B. Comparison of the CD24 and CD122 expression on E16 fetal Vγ3+ thymocytes of CCR10EGFP/EGFP (CCR10−/−) and wild type (CCR10+/+) littermates by flow cytometry. More than five mice of each genotype were analyzed. C. FACS analysis of EGFP expression on gated Vγ3+ γδ T cells of CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice vs. CCR10+/EGFP (CCR10+/−) mice. The staining of wild type cells was used as a negative control for the EGFP expression.

Defective sIEL development in CCR10 knockout mice

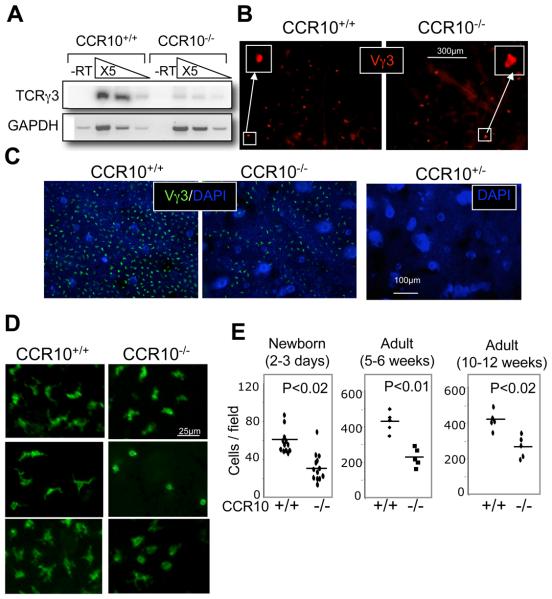

Although there was no defect in the generation and selection of Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in the fetal thymus of CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice, their seeding into the skin was severely impaired. Transcripts for Vγ3+TCRs were much lower (>10 fold) in the skin of E18 fetal CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice than their wild type littermates (Fig. 4A). In addition, the direct immunofluorescent microscopic analysis of epidermal sheets for Vγ3+ cells revealed that there were significantly fewer (2.2 fold reduction) sIELs in 2-3 day old newborn CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice than their wild type littermates (Fig. 4B and E). Compared to their corresponding wild type littermates, there were also significantly reduced numbers of sIELs in young (5-6 week old) and mature (10-12 week old) adult CCR10 knockout mice, although the extent of reduction was slightly smaller in the mature than in the young adult CCR10 knockout mice (1.6 vs. 2 fold reduction) (Fig. 4C and E; Supplementary Fig. 3). This is different from a recent report (18). The epidermal layers of adult CCR10 knockout mice had an uneven distribution of sIELs (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 3), consistent with the reduced skin-seeding by the sIEL precursors at earlier stages. In addition, sIELs in the adult CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice did not have the typical dendritic morphology seen in normal sIELs (Fig. 4D), suggesting a role of CCR10 in the sIEL morphogenesis. As a control, Langerhans cells, the other major type of epidermal immune cells, developed normally in the CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Impaired sIEL development in CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice. A. Comparison of TCRγ3 transcripts in fetal skin of CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Skin RNAs of E18 fetal CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild-type mice were subjected to semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis for rearranged TCRγ3. -RT, no reverse transcription. GAPDH was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated twice. B. Immunofluorescent microscopic analysis of epidermal sheets of the 2-3 day old newborn CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice for Vγ3+ sIELs. Epidermal sheets of the back skin were stained with biotin conjugated anti-Vγ3 antibodies followed with Alexa 647 conjugated streptavidin. C. Immunofluorescent microscopic analysis of epidermal sheets of 5-6 week old adult CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice for Vγ3+ sIELs. Ear epidermal sheets were co-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-Vγ3 antibody and DAPI. The picture on the right was stained with DAPI and used as a control for endogenous EGFP signals. D. High-magnification immunofluorescent microscopy of ear epidermal sheets of adult CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice for morphology of Vγ3+ sIELs. Images of three pairs of littermates were shown. E. Quantitative comparison of numbers of Vγ3+ sIELs in the CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice of different ages. The number of Vγ3+ sIELs was calculated from the immunofluorescent microscopy of epidermal sheets with at least five fields counted for each mouse. One dot represents average number of Vγ3+ sIELs per field from one mouse.

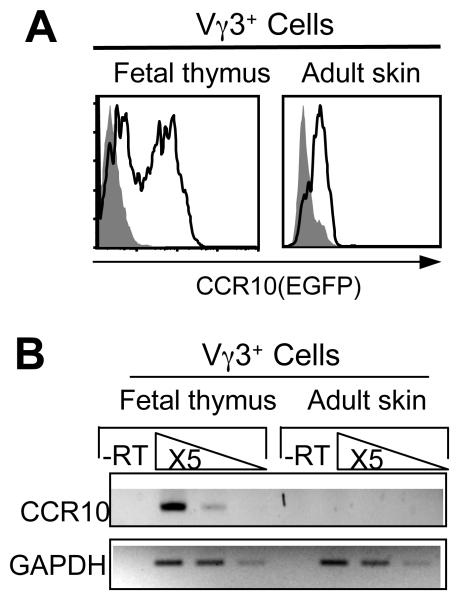

Temporally regulated CCR10 expression in sIELs and their precursors

Surprisingly, in spite of the defects in the sIEL development in absence of CCR10, we could not detect EGFP signals in the sIELs of adult CCR10+/EGFP or CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice under the fluorescent microscope (Fig. 4C, the right panel; and data not shown). This was not due to leakage of the highly soluble EGFP proteins out of the sIELs during the preparation process of epidermal sheets since this was a case even when we did not treat the epidermal sheets with any permeabilizing reagents. In addition, with the more quantitative flow cytometric analysis, we only detected very weak EGFP signals of Vγ3+ sIELs isolated from adult CCR10+/EGFP mice, in clear contrast to those of CCR10+/EGFP fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that the expression of CCR10 on sIELs of adult mice is downregulated from the expression level of their fetal thymic precursors. Directly confirming this, the level of CCR10 transcripts in purified Vγ3+ sIELs of wild type adult mice was much lower than that of purified CD122+ Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes (Fig. 5B). Considering that keratinocytes are in direct contact with sIELs and express high levels of the ligand CCL27 for CCR10, the temporally regulated CCR10 expression on sIELs and their precursors is likely involved in calibration of the CCR10/ligand interaction strength for the migration and distribution of sIELs within the skin.

Increased accumulation of Vγ3+ γδ T cells in dermal regions of the skin in CCR10 knockout mice

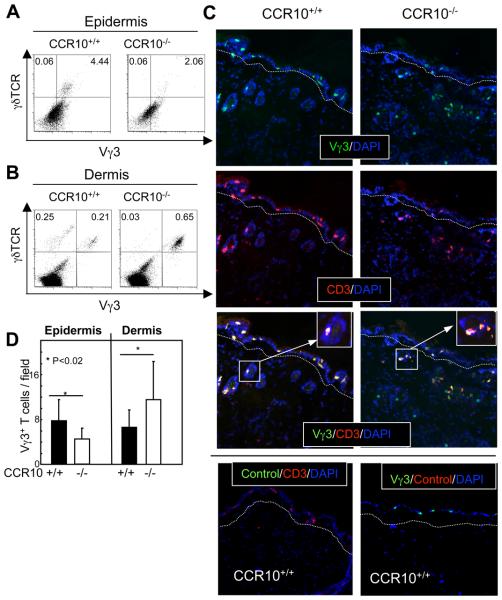

To test whether CCR10 is involved in maintaining the proper distribution of sIELs within the skin, we isolated cells from epidermal and dermal regions of the skin separately and analyzed them for the Vγ3+ T cells by flow cytometry. There were about two-fold lower percentages of epidermal Vγ3+ T cells in CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice than in wild type controls (Fig. 6A), confirming that the sIEL development is impaired in the CCR10-knockout mice. In contrast, there was more than a three-fold increase in the percentage of Vγ3+ γδ T cells of cells isolated from the dermis of CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice than from wild type mice (Fig. 6B), demonstrating that CCR10 is important for the proper distribution of Vγ3+ cells within the skin. In addition, we consistently observed lower percentages of Vγ3− γδ T cells in the dermis of CCR10 knockout than wild type mice, suggesting that the absence of CCR10 might affect other T cell populations within the dermis.

Figure 6.

Abnormal accumulation of Vγ3+ γδ T cells in dermal regions of CCR10 knockout mice. A. FACS analysis for Vγ3+ sIELs in cells isolated from epidermis of the CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice. B. FACS analysis for Vγ3+ T cells in cells isolated from the dermal regions of the CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice. A set of representative plots of at least three experiments is shown. C. Immunofluorescent microscopy of skin sections of the CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice co-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-Vγ3 and Alexa-647 conjugated anti-CD3 antibodies. The dashed lines run along borders of the epidermis and dermis. Isotype controls are shown at the bottom. D. Quantification of epidermal and dermal Vγ3+ cells of the CCR10EGFP/EGFP and wild type mice based on the immunofluorescent microscopic analyses in the panel C. Five mice of each genotype were analyzed with more than 10 fields counted for each mouse.

We then performed immunofluorescent microscopic analysis of skin sections to directly visualize Vγ3+ T cells in the epidermis and dermis. In wild type mice, a majority of Vγ3+ T cells reside in the epidermis while many of them were also found in the dermis, specifically in the epithelia surrounding hair follicles (Fig. 6C-D; Supplementary Fig. 5). Compared to the wild type controls of corresponding compartments, there were fewer Vγ3+ cells in the epidermis but more Vγ3+cells in the dermis of the CCR10 knockout mice (Fig. 6C-D). As a result, CCR10 knockout mice on average had much more Vγ3+ cells in the dermis than in the epidermis (Fig. 6D), confirming that CCR10 is indeed important in maintaining the proper distribution of Vγ3+ cells within the skin. In addition, a majority of Vγ3+ cells in the dermis of CCR10 knockout mice still resided in the epithelia surrounding the hair follicles, while some of them could be found outside the hair follicles (Fig. 6C).

Defective migration of CCR10-knockout Vγ3+ sIEL precursors towards the skin

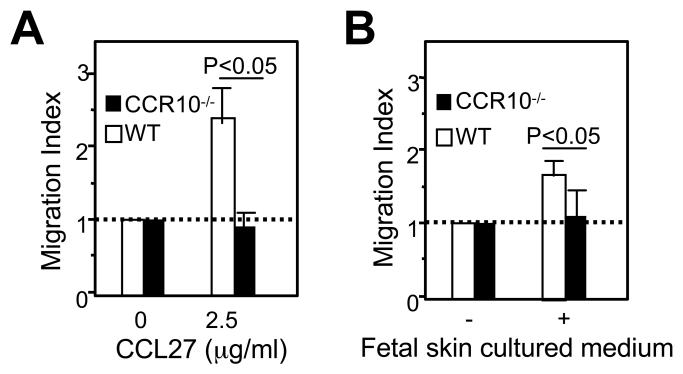

Considering the dominant expression of the CCR10 ligand CCL27 by keratinocytes, the most likely underlying mechanism for the number, morphology, and distribution of Vγ3+ γδ T cells in the skin of CCR10 knockout mice is due to the defective homing and positioning of the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in(to) the skin in absence of the CCR10/ligand interaction. On the other hand, the CCR10/ligand interaction is unlikely involved in the survival/proliferation of sIELs in the skin, since sIELs expanded in the CCR10 knockout mice as much as in wild types from the new-born to adult stages and the reduction in numbers of sIELs in the CCR10 knockout mice is in fact less evident when the mice become older (Fig. 4E). This suggests that the CCR10-deficient sIEL precursors are capable of a homeostatic expansion. Therefore, we performed in vitro migration assays to test directly whether the CCR10-deficient Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes were defective in migration to the skin. As expected, the CCR10EGFP/EGFP Vγ3+ thymocytes were unable to migrate towards CCL27 at all, indicating that CCR10 is the only chemokine receptor expressed by the sIEL precursors for CCL27 (Fig. 7A). Importantly, the CCR10EGFP/EGFP Vγ3+ thymocytes also had defects in the migration towards culture media of the fetal skin (Fig. 7B), suggesting that they have impaired ability in the CCL27-mediated skin homing.

Figure 7.

Defective migration of CCR10EGFP/EGFP fetal thymic Vγ3+ cells towards CCL27 and skin in the in vitro chemotaxis assay. The migration index is calculated as a ratio of numbers of Vγ3+ cells migrating into the bottom chamber in presence of CCL27 (A), conditioned medium of fetal skin culture (B) vs. medium only. The experiments were repeated twice.

Discussion

Complementing the SLO-residing conventional T cells, various populations of non-classical, innate-like T cells predominantly localize in specific non-lymphoid tissues as the first line of defence. However, development of the tissue-specific T cells is not well understood. Our study reported herein on murine sIELs found that compared to other thymic T cell subsets, the fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors had a unique skin-homing property (CCR10highαEβ7highCCR7lowCD62LlowCCR9lowα4β7low) that plays an important role for their peripheral localization. Using a newly generated strain of CCR10-knokout/EGFP-knockin mice, we demonstrate that the positive selection-associated upregulation of CCR10 on the fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is important for their seeding into the skin. In addition, we also show that CCR10 is important for maintaining the proper morphology and epidermal distribution of Vγ3+ γδ T cells within the skin.

The skin-seeding, dendritic morphology, and proper epidermal distribution of sIELs are likely linked events mediated by the CCR10/ligand interaction. In the skin, keratinocytes of the epidermis highly express CCL27, a ligand for CCR10 (17, 33). In absence of CCR10/CCL27 signals, fetal thymic Vγ3+ T cells could not migrate into the epidermis efficiently and might end up in other regions of the skin and possibly other tissues. However, we did not find Vγ3+ cells in several tissues we tested in adult CCR10 knockout mice, including the spleen, lymph node and female reproductive tract (data not shown). This suggests that even if the CCR10-knockout fetal thymic Vγ3+ cells migrate into these tissues other than the skin, they might not be able to survive and proliferate.

Since sIELs are in direct contact with keratinocytes in the epidermis, CCL27 secreted by keratinocytes likely acts on CCR10 expressed on sIELs in a concentrated fashion to help maintain the morphology and location of the Vγ3+ cells within the epidermal region. Therefore, in absence of CCR10/CCL27 signals, the Vγ3+ cells could neither maintain their dendritic shape nor attain the epidermal location properly, resulting in their redistribution in the dermal region of the skin. Interestingly, the Vγ3+ cells in dermal regions of the CCR10 knockout mice were still predominantly localized in the hair follicle regions, like in wild type mice (34), suggesting that they are specifically attracted to these sites. It will be interesting to determine what other molecules are involved in their positioning in the follicles. It was previously reported that sIELs rounded up in response to the local stimulation and moved away from the epidermis (35). It is possible that the morphological changes of sIELs due to absence of CCR10-mediated signals are analogous to the induced morphological changes during their activation.

The effects of CCR10 on the migration, morphology and in-skin distribution of Vγ3+ sIELs is associated with the regulated expression of CCR10 in the sIELs and their precursors. This is likely involved in the calibration of the interaction strength between sIELs and neighbouring keratinocytes for their proper distribution and functions. Likely, a high level of CCR10 expression is needed for the efficient migration of the sIEL precursors in(to) the skin but not for their retention once they are inside. On the other hand, continuous strong CCR10/ligand interaction could break the homeostasis balance of sIELs and other skin cells and might affect functions of sIELs, especially considering that the skin can upregulate the expression of CCL27 during inflammation (36). Although the sIELs had downregulated CCR10 expression from the level expressed by their precursors, they seem to upregulate the expression of other chemokine receptors. A recent report found that while very few fetal thymic sIEL precursors expressed CCR4, nearly all the adult sIELs of the skin did, suggesting that CCR4 is upregulated on the sIELs or that CCR4+ sIELs selectively expanded in the skin (18). These indicate that there is a dynamic switch in the expression of chemokine receptors on sIELs from their fetal thymic precursors that might be important for their proper maintenance and functions in the skin.

In spite of the severely impaired skin-seeding of the CCR10-deficient sIEL precursors at the fetal stage, the number of sIELs in adult CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice was only mildly reduced from that of wild type mice while the number of Vγ3+ γδ T cells in the dermal region was even higher in CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice. This suggests that besides CCR10, other homing molecules are able to direct their localization in the skin. Possible candidate homing molecules for this include E- and P-selectin ligands (18). In addition, the results also suggest that CCR10 is not critical for survival or proliferation of sIELs in the skin. In fact, the severe early defect in the skin-seeding by the CCR10EGFP/EGFP sIEL precursors is gradually compensated for during the phase of sIEL expansion in the skin when the mice become older. Therefore, given time, the fewer CCR10EGFP/EGFP sIEL precursors that made it to the skin could expand efficiently to reach the level of the wild type mice. This might explain why an earlier report using a different strain of CCR10 knockout mice found no defect of sIELs in adult CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice (18). While local factors in the skin responsible for the survival and expansion of sIELs are not fully elucidated, one possible explanation is IL-15 produced by certain skin cells, which could act on the IL-15 receptors expressed by the sIELs. Reports show that no sIELs developed in IL-15 knockout mice or CD122 (IL-15Rβ) knockout mice (37, 38).

Besides providing the direct evidence that CCR10 is dynamically expressed by the sIELs and their precursors, our studies with the CCR10knockout/EGFP-knockin mice also revealed that CCR10 is expressed on significant percentages of several other non-conventional thymic T cell subsets but rarely on the conventional CD4+ or CD8+ αβ T cells. Although the biological importance of these observations requires further investigation, the expression pattern is consistent with the fact that many of the non-conventional T cells preferentially localize into epithelial tissues such as intestines, reproductive tracts and skin that express the ligands for CCR10. This supports the notion that different thymic development and selection processes of the specific T cell subsets might endow them with specific homing properties for unique peripheral localizations. This is particularly intriguing considering that the various non-classical, tissue-specific lymphocyte populations, such as mucosal associated invariant T cells (MALT), CD8αα+ T cells, NK T cells and even B1 B cells, all undergo unique developmental processes in the thymus (or bone marrow) that are different from those of conventional T/B cells (1, 39-43)(44)(45). The CCR10-knckout/EGFP-knockin mouse would be a useful tool to study how the development processes of specific thymic T cell subsets are involved in the CCR10 expression and to determine how the expression of CCR10 is involved in their peripheral localization. In addition, it will be interesting to understand how the regulated expression of CCR10 occurs in the local skin tissue. Like the upregulation of CCR10 in the positively selected fetal thymic sIEL precursors, its downregulation in sIELs likely depend on the local environment. Although remaining to be addressed, this downregulation is not due to a negative feedback mechanism associated with the CCR10/ligand interaction in the skin, since the EGFP signal was downregulated on sIELs of CCR10EGFP/EGFP mice that did not express CCR10. Instead, this might be a process associated with the expansion, maintenance and function of sIELs in the skin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Joonsoo Kang, David Wiest, David Raulet, Jianke Zhang and Avery August for discussion and comments, Thomas Salada for the ES cell microinjection.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (N.X.) and, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco Settlement Funds (N.X.). The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions.

References

- 1.Hayday AC. [gamma][delta] cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annual Review of Immunology. 2000;18:975–1026. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raulet D, Spencer D, Hsiang Y-H, Goldman J, Bix M, Liao N-S, Zijlstra M, Jaenisch R, Correa I. Control of γδ T cell development. Immunol. Rev. 1991;120:185–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim CH, Witherden DA, Havran WL. Characterization and TCR variable region gene use of mouse resident nasal gammadelta T lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:1259–1263. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong N, Raulet DH. Development and selection of gammadelta T cells. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:15–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girardi M, Oppenheim DE, Steele CR, Lewis JM, Glusac E, Filler R, Hobby P, Sutton B, Tigelaar RE, Hayday AC. Regulation of cutaneous malignancy by gammadelta T cells. Science. 2001;294:605–609. doi: 10.1126/science.1063916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girardi M, Lewis J, Glusac E, Filler RB, Geng L, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE. Resident skin-specific gammadelta T cells provide local, nonredundant regulation of cutaneous inflammation. J Exp Med. 2002;195:855–867. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jameson J, Ugarte K, Chen N, Yachi P, Fuchs E, Boismenu R, Havran WL. A role for skin gammadelta T cells in wound repair. Science. 2002;296:747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1069639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong N, Kang CH, Raulet DH. Redundant and unique roles of two enhancer elements in the TCR gamma locus in gene regulation and gamma delta T cell development. Immunity. 2002;16:453–463. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallick-Wood C, Lewis JM, Richie LI, Owen MJ, Tigelaar RE, Hayday AC. Conservation of T cell receptor conformation in epidermal γδ cells with disrupted primary Vγ gene usage. Science. 1998;279:1729–1733. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hara H, Kishihara K, Matsuzaki G, Takimoto H, Tsukiyama T, Tigelaar RE, Nomoto K. Development of dendritic epidermal T cells with a skewed diversity of gamma delta TCRs in V delta 1-deficient mice. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:3695–3705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrero I, Wilson A, Beermann F, Held W, MacDonald HR. T cell receptor specificity is critical for the development of epidermal gammadelta T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1473–1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong N, Kang C, Raulet DH. Positive selection of dendritic epidermal γδ T cell precursors in the fetal thymus determines expression of skin-homing receptors. Immunity. 2004;21:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis JM, Girardi M, Roberts SJ, Barbee SD, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE. Selection of the cutaneous intraepithelial gammadelta+ T cell repertoire by a thymic stromal determinant. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:843–850. doi: 10.1038/ni1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyden LM, Lewis JM, Barbee SD, Bas A, Girardi M, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE, Lifton RP. Skint1, the prototype of a newly identified immunoglobulin superfamily gene cluster, positively selects epidermal gammadelta T cells. Nat Genet. 2008;40:656–662. doi: 10.1038/ng.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uche UN, Huber CR, Raulet DH, Xiong N. Recombination signal sequence-associated restriction on TCRdelta gene rearrangement affects the development of tissue-specific gammadelta T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:4931–4939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morales J, Homey B, Vicari AP, Hudak S, Oldham E, Hedrick J, Orozco R, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, McEvoy LM, Zlotnik A. CTACK, a skin-associated chemokine that preferentially attracts skin-homing memory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14470–14475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X, Campbell JJ, Kupper TS. Embryonic trafficking of {gamma}{delta} T cells to skin is dependent on E/P selectin ligands and CCR4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912943107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992;69:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan S, Bergstresser P, Tigelaar R, Streilein JW. FACS purification of bone marrow-derived epidermal populations in mice: Langerhans cells and Thy-I+ dendritic cells. J. Invest. Derm. 1985;84:491–495. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12273454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luci C, Reynders A, Ivanov II, Cognet C, Chiche L, Chasson L, Hardwigsen J, Anguiano E, Banchereau J, Chaussabel D, Dalod M, Littman DR, Vivier E, Tomasello E. Influence of the transcription factor RORgammat on the development of NKp46+ cell populations in gut and skin. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyauchi S, Hashimoto K. Epidermal Langerhans cells undergo mitosis during the early recovery phase after ultraviolet-B irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:703–708. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldman J, Spencer D, Raulet D. Ordered rearrangement of variable region genes of the T cell receptor gamma locus correlates with transcription of the unrearranged genes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1993;177:729–739. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morteau O, Gerard C, Lu B, Ghiran S, Rits M, Fujiwara Y, Law Y, Distelhorst K, Nielsen EM, Hill ED, Kwan R, Lazarus NH, Butcher EC, Wilson E. An indispensable role for the chemokine receptor CCR10 in IgA antibody-secreting cell accumulation. J Immunol. 2008;181:6309–6315. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunkel EJ, Kim CH, Lazarus NH, Vierra MA, Soler D, Bowman EP, Butcher EC. CCR10 expression is a common feature of circulating and mucosal epithelial tissue IgA Ab-secreting cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1001–1010. doi: 10.1172/JCI17244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ueno T, Hara K, Willis MS, Malin MA, Hopken UE, Gray DH, Matsushima K, Lipp M, Springer TA, Boyd RL, Yoshie O, Takahama Y. Role for CCR7 ligands in the emigration of newly generated T lymphocytes from the neonatal thymus. Immunity. 2002;16:205–218. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arbones ML, Ord DC, Ley K, Ratech H, Maynard-Curry C, Otten G, Capon DJ, Tedder TF. Lymphocyte homing and leukocyte rolling and migration are impaired in L-selectin-deficient mice. Immunity. 1994;1:247–260. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schon MP, Arya A, Murphy EA, Adams CM, Strauch UG, Agace WW, Marsal J, Donohue JP, Her H, Beier DR, Olson S, Lefrancois L, Brenner MB, Grusby MJ, Parker CM. Mucosal T lymphocyte numbers are selectively reduced in integrin alpha E (CD103)-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1999;162:6641–6649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Soto H, Oldham ER, Buchanan ME, Homey B, Catron D, Jenkins N, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Nguyen N, Abrams J, Kershenovich D, Smith K, McClanahan T, Vicari AP, Zlotnik A. Identification of a novel chemokine (CCL28), which binds CCR10 (GPR2) J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22313–22323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazarus NH, Kunkel EJ, Johnston B, Wilson E, Youngman KR, Butcher EC. A common mucosal chemokine (mucosae-associated epithelial chemokine/CCL28) selectively attracts IgA plasmablasts. J Immunol. 2003;170:3799–3805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwasaki A. Mucosal dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:381–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nestle FO, Di Meglio P, Qin JZ, Nickoloff BJ. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:679–691. doi: 10.1038/nri2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Homey B, Wang W, Soto H, Buchanan ME, Wiesenborn A, Catron D, Muller A, McClanahan TK, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Orozco R, Ruzicka T, Lehmann P, Oldham E, Zlotnik A. Cutting edge: the orphan chemokine receptor G protein-coupled receptor-2 (GPR-2, CCR10) binds the skin-associated chemokine CCL27 (CTACK/ALP/ILC) J Immunol. 2000;164:3465–3470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paus R, van der Veen C, Eichmuller S, Kopp T, Hagen E, Muller-Rover S, Hofmann U. Generation and cyclic remodeling of the hair follicle immune system in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:7–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strid J, Roberts SJ, Filler RB, Lewis JM, Kwong BY, Schpero W, Kaplan DH, Hayday AC, Girardi M. Acute upregulation of an NKG2D ligand promotes rapid reorganization of a local immune compartment with pleiotropic effects on carcinogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:146–154. doi: 10.1038/ni1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Homey B, Alenius H, Muller A, Soto H, Bowman EP, Yuan W, McEvoy L, Lauerma AI, Assmann T, Bunemann E, Lehto M, Wolff H, Yen D, Marxhausen H, To W, Sedgwick J, Ruzicka T, Lehmann P, Zlotnik A. CCL27-CCR10 interactions regulate T cell-mediated skin inflammation. Nat Med. 2002;8:157–165. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawai K, Suzuki H, Tomiyama K, Minagawa M, Mak TW, Ohashi PS. Requirement of the IL-2 receptor beta chain for the development of Vgamma3 dendritic epidermal T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:961–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Creus A, Van Beneden K, Stevenaert F, Debacker V, Plum J, Leclercq G. Developmental and functional defects of thymic and epidermal V gamma 3 cells in IL-15-deficient and IFN regulatory factor-1-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:6486–6493. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Treiner E, Duban L, Bahram S, Radosavljevic M, Wanner V, Tilloy F, Affaticati P, Gilfillan S, Lantz O. Selection of evolutionarily conserved mucosal-associated invariant T cells by MR1. Nature. 2003;422:164–169. doi: 10.1038/nature01433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardy RR. B-1 B cell development. J Immunol. 2006;177:2749–2754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambolez F, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Thymic differentiation of TCR alpha beta(+) CD8 alpha alpha(+) IELs. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:178–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tilloy F, Treiner E, Park SH, Garcia C, Lemonnier F, de la Salle H, Bendelac A, Bonneville M, Lantz O. An invariant T cell receptor alpha chain defines a novel TAP-independent major histocompatibility complex class Ib-restricted alpha/beta T cell subpopulation in mammals. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1907–1921. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.12.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamagata T, Mathis D, Benoist C. Self-reactivity in thymic double-positive cells commits cells to a CD8 alpha alpha lineage with characteristics of innate immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:597–605. doi: 10.1038/ni1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen KD, Shin S, Chien YH. Cutting edge: Gammadelta intraepithelial lymphocytes of the small intestine are not biased toward thymic antigens. J Immunol. 2009;182:7348–7351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Staton TL, Habtezion A, Winslow MM, Sato T, Love PE, Butcher EC. CD8+ recent thymic emigrants home to and efficiently repopulate the small intestine epithelium. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:482–488. doi: 10.1038/ni1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.