Abstract

Background

HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects minority groups in the United States, especially in the rural southeastern states. Poverty and lack of access to HIV care, including clinical trials, are prevalent in these areas and contribute to HIV stigma. This is the first study to develop a conceptual model exploring the relationship between HIV stigma and the implementation of HIV clinical trials in rural contexts to help improve participation in those trials.

Methods

We conducted focus groups with HIV service providers and community leaders, and individual interviews with people living with HIV/AIDS in six counties in rural North Carolina. Themes related to stigma were elicited. We classified the themes into theoretical constructs and developed a conceptual model.

Results

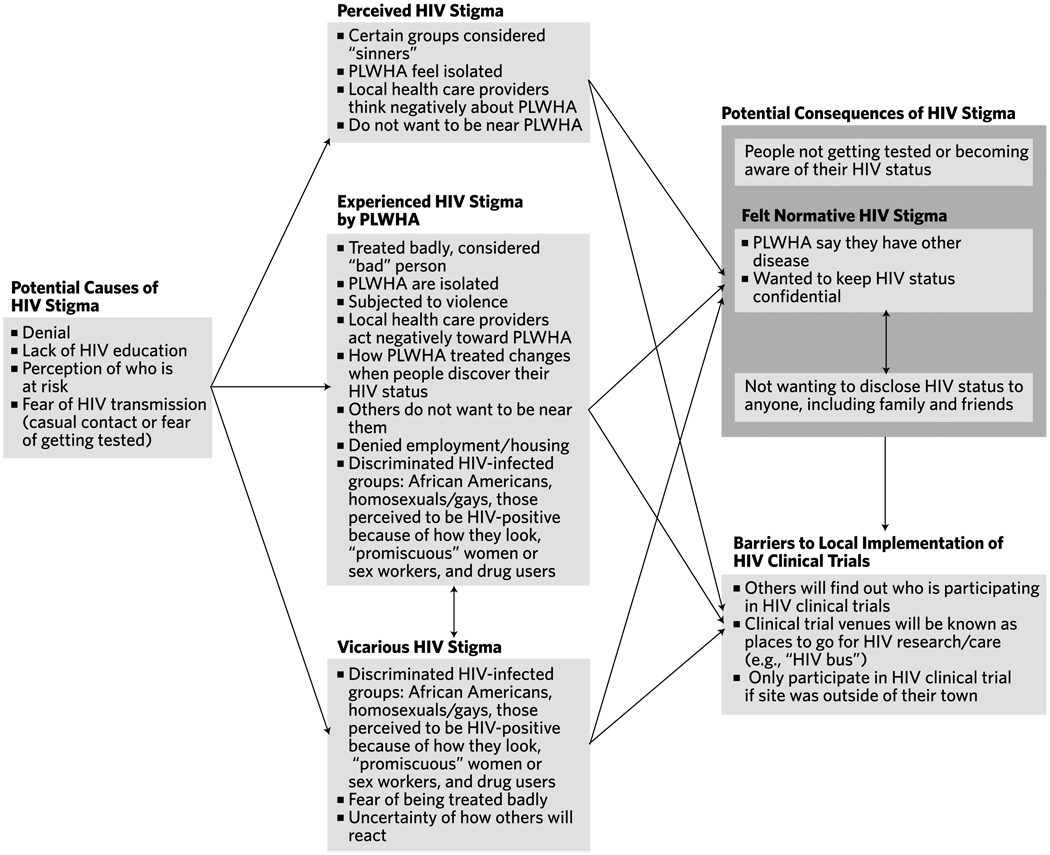

HIV stigma themes were classified under the existing theoretical constructs of perceived, experienced, vicarious, and felt normative stigma. Two additional constructs emerged: causes of HIV stigma (e.g., low HIV knowledge and denial in the community) and consequences of HIV stigma (e.g., confidentiality concerns in clinical trials). The conceptual model illustrates that the causes of HIV stigma can give rise to perceived, experienced, and vicarious HIV stigma, and these types of stigma could lead to the consequences of HIV stigma that include felt normative stigma.

Limitations

Understanding HIV stigma in rural counties of North Carolina may not be generalizeable to other rural US southeastern states.

Conclusion

The conceptual model emphasizes that HIV stigma—in its many forms—is a critical barrier to HIV clinical trial implementation in rural North Carolina.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, stigma, clinical trials, minority groups, research participation

The epidemiology and demographics of HIV/AIDS have evolved over the last 25 years in the United States, resulting in the highest rates of new infection among minority populations, particularly among African American and Latino populations. In addition, there has been a shift in new HIV/AIDS cases from large northeastern and western metropolitan areas to the southeast, where over 43% of residents live in rural areas.1,2 The southeast represents six southern states, including North Carolina, that are disproportionately affected by the AIDS epidemic. In North Carolina, 68% of the total number of AIDS cases reported in 2007 were African Americans and 8% were Latinos.3

The rise of the AIDS epidemic in southeastern rural areas may be exacerbated by poverty and lack of access to HIV prevention and care that is more readily available in US urban areas.1,2 Such socioeconomic conditions create an environment that can engender HIV stigma and allow it to flourish. An extensive body of literature exists that identifies HIV stigma as a complex sociocultural barrier that negatively affects preventive behaviors, including condom use and HIV test-seeking behaviors; care-seeking behaviors relating to diagnosis and compliance; quality of care for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA); and perception and treatment of PLWHA among family, friends, partners, health care providers, and the larger community.4,5 For example, in urban areas, HIV stigma was three times more likely to be associated with reduced access to care among low-income, HIV-infected individuals even after controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and biomarkers for HIV infection.6 For African Americans and Latinos living with HIV/AIDS in one of the southeastern states, stigma and shame have been identified as themes affecting medication adherence.7 These studies’ findings are of particular importance because lack of access, or delayed access to care, may result in more advanced stages of HIV disease at clinical presentation and/or increased resistance to first-line antiretroviral therapies.

While qualitative and quantitative studies have demonstrated an association between HIV stigma and access to HIV care among racial/ethnic minority groups, little work has been done on the impact of HIV stigma on access to clinical trials. HIV clinical trials have been, and continue to be, a source of care for PLWHA, especially PLWHA who have no health insurance coverage. Racial/ethnic minority groups, however—particularly African Americans and Latinos—have been disproportionately underrepresented in HIV research and clinical trials despite formal policies and concerted efforts on the frontline to increase their inclusion as subjects in clinical trials.8,9 If HIV stigma is a barrier to HIV prevention and care services in impoverished and rural minority communities, it may also affect HIV clinical trial participation in these communities as well. Applying theory to understand the relationship between HIV stigma and HIV clinical trial participation in rural US communities will be useful in expanding our understanding of health disparities in HIV care access and utilization.

In recent years, theoretical frameworks have been posed to explore the complexity of HIV stigma and its impact in communities. The simplest theoretical framework breaks down HIV stigma into perceived stigma, experienced stigma, and internalized stigma.4 Perceived stigma is how PLWHA feel that they are being negatively treated by partners, family, friends, health care providers, and members of their community because of their HIV status. Experienced stigma is an act of discrimination towards PLWHA that includes denial of health care, education, or employment, or isolation from family members. Internalized stigma is the negative self-image PLWHA may have resulting from perceived and/ or experienced stigma.

An alternative framework assumes that HIV stigma begins at the societal level where inequalities in social, political, and economic power enable stigmatization.5 In this framework, HIV stigma can be manifested by labeling, negatively stereotyping, separating PLWHA from non-infected community members based on other discredited attributes (e.g., being an injection drug user or a commercial sex worker), and by racism and sexism. In this understanding, the most direct level of HIV stigma is experienced stigma, which can be acts of discrimination by non-stigmatized individuals or acts of discrimination toward PLWHA at the institutional level (e.g., being fired for having HIV).

Another useful theoretical framework incorporates both perceived and experienced stigma at the individual and community levels, in addition to internalized stigma.10 Moreover, this framework includes two new concepts of HIV stigma: felt normative stigma and vicarious stigma. Felt normative stigma is a protective mechanism for PLWHA against experiencing stigma (e.g., passing as a member of the non-stigmatized community). Vicarious stigma happens when PLWHA hear stories of experienced stigma and these stories become real to them, even though they may not have directly experienced discrimination themselves.

Our study is one element of a larger community-based project called Project EAST (Education and Access to Services and Testing) that is examining individual, provider, and community level factors that influence participation of rural racial/ethnic minorities in HIV/AIDS research, and which will test the feasibility of implementing HIV/AIDS clinical trials in local communities. The first phase of Project EAST utilized qualitative methods to obtain preliminary data about community views of HIV/AIDS and to ascertain the feasibility of clinical trial implementation in rural, minority communities. One mode of implementation that was highlighted was using a mobile unit to increase rural communities’ access to clinical trials. Issues of HIV stigma were dominant and emergent themes in this inquiry. Thus, the purpose of the current study—using the existing theoretical constructs for HIV stigma as a guide—was to develop a conceptual model that explored the relationship between HIV stigma and related identified themes, and how these themes may affect the implementation of HIV clinical trials in rural counties of North Carolina.

Methods

Sample

According to the 2000 US Census Bureau, almost 32% of the population in North Carolina lives in what is defined as a “rural area.”11 We conducted focus groups with HIV service providers and community leaders, and individual in-person interviews with PLWHA in six of these predominantly rural counties in North Carolina, representing two three-county communities. Moreover, these six counties were also selected due to their moderate HIV prevalence, based on HIV/AIDS surveillance at the end of 2007, ranging from 0.5%-1%.3 In qualitative methodology, sample size and power depend on purposeful selection of participants to achieve an information-rich and heterogeneous sample that represents the target populations of interest;12 in our case, we were interested in sampling HIV service providers, community leaders, and PLWHA from each of the six North Carolina counties.

To achieve data saturation,13 we conducted a total of 11 focus groups with 4–10 participants in each focus group. The majority of these focus groups were stratified by community leader vs. HIV service providers and by county, but the exceptions included: one focus group with Spanish-speaking community leaders from one three-county community in which over 40% of the PLWHA are Latinos, one combination community leader/provider focus group from one county, and one provider focus group representing three of the counties. HIV service providers were defined as those who provide direct care or services to PLWHA, and community leaders were defined as those who could have an influence in engaging their respective communities in HIV/AIDS clinical trials.

Similarly, we recruited between five to eight PLWHA study participants from each of the six counties for a total of 35 individual PLWHA in-person interviews to achieve data saturation. PLWHA were recruited through local HIV/AIDS case management and clinical care programs in each of the participating counties. Inclusion criteria included self-identifying as African American or Latino, ability to speak English or Spanish, and residing in one of the six counties.

Data Collection

The Project EAST design, methods of recruitment, data collection, and data analysis were approved by the University of North Carolina (UNC) Biomedical Institutional Review Board and the UNC General Clinical Research Center on August 29, 2006.

Instrument

Separate semi-structured interview guides were developed for the focus groups and the PLWHA interviews. For both, semi-structured interview guides consisted of parallel a priori conceptual domains that included:

-

■

community and personal views about HIV/AIDS,

-

■

views about HIV research or HIV clinical trials,

-

■

views about how to bring HIV clinical trials into rural communities, and

-

■

views about different mechanisms (including a mobile van) to conduct HIV clinical trials.

For the PLWHA interviews, additional, a priori conceptual domains included: disclosure and preferences relating to participation in HIV clinical trials. Questions and probes were developed for each of the a priori conceptual domains, and those that elicited HIV stigma or related themes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected Conceptual Domains and Questions/Probes in the Semi-Structured Interview Guide

| Conceptual Domain | Questions/Probes in Interview Guide |

|---|---|

| Community and personal views about HIV/AIDS and PLWHA |

|

| Barriers to bringing HIV clinical trials into rural communities | What makes it difficult to bring HIV clinical trials into communities? |

| Views about a mobile van | What about using a mobile van in your community as a way for people who are HIV-positive to enroll and participate in clinical trials? |

| Additional Questions Asked to PLWHA | |

| Disclosure | Who have you not told that you have HIV? Probe: Why didn’t you tell them? |

| Preferences on where to participate in HIV clinical trials | Would it be easier or better for you to participate in an HIV clinical trial here in your community or would you prefer to go to University, A, B, or C? Probe for rationale. |

Recruitment

HIV service provider and community leader potential focus group participants were recruited by a community outreach specialist from each three-county community. Each community outreach specialist developed a master list of potential participants for the community leader groups by identifying individuals from political, educational, grassroots, economic, media, religious, and social welfare-related community segments. A similar master list was comprised for service providers that included physicians, case managers, health educators, and other clinical practitioners. Each community outreach specialist made phone contact with a purposive sample of leaders to ensure a cross-representation across community segments and provider types for data collection.

Focus groups were convened at a centrally-located facility within each three-county region and were conducted by a facilitator and notetaker. Each meeting was digitally recorded, and each lasted an average of 90 minutes. At the beginning of a focus group, written informed consent was obtained, followed by a question and answer discussion using the semi-structured interview guide, and demographic information was collected from each of the participants at the end. A financial incentive of $20 as well as a meal were provided to focus group participants. Focus group data were collected over a period of three and a half months.

PLWHA potential participants were contacted by their case manager or the community outreach specialist to explain the study. Each interview was digitally recorded and lasted an average of 45 minutes. At the beginning of an interview, written informed consent was obtained, followed by a question and answer discussion using the semi-structured interview guide, and demographic information was collected from each of the participants at the end. A financial incentive of $20 was given to all PLWHA participants.

Data Analysis

All focus group and PLWHA interviews were electronically transcribed into Microsoft Word documents by a professional transcriptionist. Accuracy of the transcription was verified by a member of the research team, and any identifying information within the interviews was redacted to protect the confidentiality of participants. The transcribed interviews were imported into the qualitative software program, Atlas. ti, v.5.2. The first phase of qualitative data analysis involved identifying themes from the questions asked and developing a codebook that reflected a thematic coding structure underlying both a priori conceptual domains/questions and emerging conceptual domains. Separate codebooks were developed for the focus group and PLWHA interview transcripts. Codes for each theme were assigned to text using Atlas.ti by a pair of coders per transcript, and 100% inter-coder reliability was established by having the coders resolve any coding differences between them. The codebooks went through a series of iterations to produce final versions that could be used for the interpretative phase of data analysis. Using this approach, the first phase of the analytical process yielded discrete and systematically coded textual data.

In the second phase of data analysis, we extracted coded textual data reflecting HIV stigma themes and categorized them under the existing theoretical constructs—perceived stigma (from PLWHA or community), experienced stigma, internalized stigma, felt normative stigma, and vicarious stigma—identified in the literature. Stigma-related themes that did not fall neatly under the existing theoretical constructs were classified under “other” to denote potential emerging themes that could be associated with HIV stigma. These data were reviewed to identify their co-occurrences, and a conceptual framework was then developed that explored the possible relationships between HIV stigma, its related themes, and how these themes may affect local implementation of HIV clinical trials in rural North Carolina communities.

Results

Sociodemographics

Tables 2 and 3 present the sociodemographics of focus group and individual interview participants. The majority of community leader focus group participants were African American or Latino (82.5%), female (72.5%), and had completed some college or graduate school (92.5%). Similarly, service provider participants were primarily African American or Latino (69.4%), female (72.2%), and had completed some college or graduate school (94.4%). For PLWHA participants, the majority were African American (88.6%), had a high school education or less (88.6%), were on antiretroviral therapy (88.6%), and had annual incomes less than $5,000 (54.3%). Related to being on antiretroviral therapy, 57% of those interviewed were “in-care,” meaning that they had gone to their medical appointments within the past six months.

Table 2.

Sociodemographics of Focus Group Participants

| Demographics | Community Leaders (n = 40) |

HIV Service Providers (n = 36) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean 43.4 (SD = 11.18) | Mean 40.6 (SD = 11.28) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 26 (65.0%) | 21 (58.3%) |

| Latino | 7 (17.5%) | 4 (11.1%) |

| White | 5 (12.5%) | 11 (30.6%) |

| Multi-Racial/Ethnic | 2 (5.0%) | — |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 11 (27.5%) | 10 (27.8%) |

| Female | 29 (72.5%) | 26 (72.2%) |

| Education | ||

| HS/GED or less; other training | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (5.6%) |

| Some or completed college | 21 (52.5%) | 22 (61.1%) |

| Some or completed graduate school | 16 (40.0%) | 12 (33.3%) |

Table 3.

Sociodemographics of Individual Interview Participants

| Demographics | PLWHA (n = 35) |

|---|---|

| Age | Mean 42.9 (SD = 9.135) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| African American | 31 (88.6%) |

| Latino | 4 (11.4%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 21 (60.0%) |

| Female | 14 (40.0%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/living with partner | 10 (28.6%) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 12 (34.3%) |

| Never married | 13 (37.1%) |

| Education | |

| High school or less; technical | 31 (88.6%) |

| Some or completed college | 4 (11.4%) |

| Health Insurancea | |

| Private | 1 (2.4%) |

| Public (Medicare, Medicaid, Other) | 27 (65.9%) |

| None | 13 (31.7%) |

| Receiving HIV Care | |

| Yes | 20 (57.1%) |

| No | 15 (42.9%) |

| Currently on Antiretrovirals | |

| Yes | 31 (88.6%) |

| No | 3 (8.6%) |

| Don’t know | 1 (2.9%) |

| Participated in Clinical Trial | |

| Yes | 7 (20.0%) |

| No | 27 (77.1%) |

| Don’t know | 1 (2.9%) |

| Household Income | |

| < $5K | 19 (54.3%) |

| ≥ $5K to $20K | 11 (31.4%) |

| > $20K to $40K | 2 (5.7%) |

| > $40K to $60K | 1 (2.9%) |

| Not reported | 2 (5.7%) |

Some respondents had more than one source of health insurance, making the total n for “Health Insurance” greater than the sample size of n = 35.

HIV Stigma-Related Themes Grouped by Theoretical Construct and Their Co-Occurrences

Table 4 (page 118) presents the HIV stigma themes that were elicited from the interview guide questions and our classification of these themes under existing theoretical constructs; we included an “other” category for HIV stigma-related themes that did not fall neatly into the existing constructs. Nine HIV stigma themes were elicited from the question, What do people in your community think about HIV/AIDS?; five themes from, How are PLWHA treated in the community?; five themes from, Are certain HIV-positive groups more discriminated against than others?; three themes from, What makes it difficult to bring HIV clinical trials into communities? (this included one related theme probing participants about using mobile vans); three themes from, Who have you not told that you have HIV?; and three themes from, What are your reasons for non-disclosure? We then organized each of these themes under the existing HIV stigma theoretical constructs of perceived stigma (PS), experienced stigma (ES), internalized stigma (IS), felt normative stigma (FNS), vicarious stigma (VS), and other by placing an “X” under the constructs in which we felt they best fit. Some of the stigma themes were classified under more than one construct.

Table 4.

HIV Stigma-Related Themes Grouped by Theoretical Construct

| Interview Guide Questions |

HIV Stigma Themes Elicited | HIV Stigma Theoretical Constructsa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | ES | IS | FNS | VS | Other | ||

| What do people in your community think about HIV/AIDS? | ■ Lack of HIV education | X | |||||

| ■ Denial about HIV/AIDS | X | ||||||

| ■ Perceptions of who is at-risk | X | ||||||

| ■ Fear of HIV transmission | X | ||||||

| ■ People not aware of their HIV status | X | ||||||

| ■ Certain groups considered “sinners” | X | ||||||

| ■ PLWHA say they have other disease | X | ||||||

| ■ PLWHA feel/are isolated | X | X | |||||

| ■ Local health care providers think/act negatively toward PLWHA | X | X | |||||

| How are PLWHA treated in the community? | ■ Treated badly, considered “bad” person | X | |||||

| ■ Subjected to violence | X | ||||||

| ■ How PLWHA treated changes when people discover their HIV status | X | ||||||

| ■ Do not want to be near PLWHA | X | X | |||||

| ■ Denied employment/housing | X | ||||||

| Are certain HIVpositive groups more discriminated against than others? | ■ Homosexuals/gays | X | |||||

| ■ Those perceived to be HIV-positive because of how they look | X | X | |||||

| ■ “Promiscuous” women or sex workers | X | X | |||||

| ■ Drug users | X | X | |||||

| ■ African Americans | X | X | |||||

| What makes it difficult to bring HIV clinical trials into communities? | ■ Others will find out who is participating in HIV clinical trials | X | |||||

| ■ Clinical trial venues will be known as places to go for HIV research/care | X | ||||||

| ■ Only participate in HIV clinical trial if site was outside of their town | X | ||||||

| What about using a mobile van in your community as a way for people who are HIVpositive to enroll and participate in clinical trials? | ■ Not good because the mobile van will be known as the “HIV bus” | X | |||||

| Who have you not told that you have HIV?b | ■ No one knows | X | |||||

| ■ Family members | X | ||||||

| ■ Friends | X | ||||||

| What are your reasons for non-disclosure?b | ■ Fear of being treated badly | X | |||||

| ■ Uncertainty how others will react | X | ||||||

| ■ Wanted to keep HIV status confidential | X | ||||||

PS = Perceived stigma; ES = Experienced stigma; IS = Internalized stigma; FNS = Felt normative stigma; VS = Vicarious stigma; and Other = Emerging category(ies) of stigma, or related to stigma.

Questions were asked to persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) only.

Many of the themes elicited when asking about community and personal views about HIV/AIDS were categorized as “other” given that, while they may be associated with HIV stigma, they were not HIV stigma themes by themselves. We categorized these themes as either causes or consequences of HIV stigma. For example, perceptions of those who are at risk for HIV infection co-occurred with judgments of who is or is not a “sinner” (a perceived stigma theme). Thus, perceptions of who is at risk (or of which groups get infected) could be considered a cause for negative stereotyping associated with perceived stigma (labeling at-risk groups or PLWHA as “sinners”). Isolation of PLWHA and local health care providers’ negative attitudes and interactions with PLWHA were both felt and experienced and, thus, we classified these themes under perceived and experienced stigma. The theme relating to PLWHA saying they have another disease seemed to be more related to felt normative stigma.

More direct questions asking about HIV stigma—how PLWHA are treated or which HIV-infected groups are discriminated against more than others—elicited HIV stigma themes that could be classified under experienced stigma and under vicarious stigma in cases where PLWHA participants believed that certain HIV-infected groups were stigmatized more than others, even if that perception was not based on their own experiences.

Asking PLWHA about disclosure of their HIV status identified the extent of non-disclosure to even close family members. These themes were classified in the “other” category since non-disclosure among PLWHA could be a consequence of two reasons that we classified under vicarious stigma—fear of being treated badly or the uncertainty of how others may react to their diagnosis. The third reason PLWHA do not disclose—wanting to keep their status confidential—was categorized into felt normative stigma.

Lastly, our questions asking about barriers to HIV clinical trial implementation in rural communities, and about the mobile unit specifically, elicited themes that primarily co-occurred with protecting confidentiality about their HIV status. In Table 4, we classified these themes as “other” and felt that these themes could be a consequence of many of the HIV stigma themes classified under the constructs of perceived, experienced, vicarious, and felt normative stigma.

While examples of internalized stigma probably existed in these rural communities, it is unclear from our textual data that any of the HIV stigma or HIV stigma-related themes should be classified as such. Therefore, we did not classify any of our HIV stigma themes under internalized stigma.

Conceptual Model Exploring the Impact of HIV Stigma on Local Implementation of HIV Clinical Trials

The conceptual model was developed to explore the possible relationships between HIV stigma themes and local implementation of HIV clinical trials. In reviewing co-occurrences between the themes from Table 4, Figure 1 was developed. The following quotes highlight some of the co-occurrences that were demonstrated, providing some indication of the causes of perceived HIV stigma:

[In the community, people feel] those who get HIV are the sinners and immoral, and the bad…those who are not worthy of our attention. It is a subject that never enters the church. The church does not know how to talk about it. It is something we are not going to see. (Community leader focus group participant)

It’s more of ignorance than anything else and it’s just so hard to actually enlighten people because they think that when you say the word AIDS you just sneezed on them…So, they don’t want to hear the word. You can’t really talk about it amongst people. (PLWHA participant)

Figure 1.

Exploring HIV Stigma and Its Potential Impact on Local Implementation of HIV Clinical Trials

In the first quotation, the church is highlighted as a place in the community that can engender causes of HIV stigma—lack of education, denial that HIV is a problem, perception of who is at risk—that, in turn, could affect perceptions about HIV, particularly about who contracts the disease (e.g., “sinners”). The second quotation demonstrates how denial in the community can result in PLWHA feeling isolated (i.e., not having anyone to talk to about living with HIV/AIDS).

The next quotation is about how PLWHA can be treated, demonstrating the relationship between causes of HIV stigma (e.g., fear of HIV transmission and lack of HIV education) and both perceived and experienced stigma:

It’s not a community that would support it [HIV/AIDS] and by them not being fully aware of the study of it [HIV/AIDS] they’ll shun you, they’re scared to be in your midst. They won’t allow you into their homes and they’ll very seldom shake your hand because lack of knowledge of it, they think ‘cause they shake your hand they could catch it or if they hug you they could catch it. (PLWHA participant)

Moreover, asking participants about how PLWHA are treated and which HIV-infected groups are most stigmatized, gauged the extent to which compound or layered stigma—which can be a facet of either experienced or vicarious stigma—plays a role in rural communities’ experiences with discrimination toward PLWHA (or those who are perceived to be PLWHA) because of their membership or perceived membership in other discriminated groups. The following quotation reflects the relationship between perceptions of who is at risk (cause) and HIV-infected groups that are discriminated against (experienced or vicarious stigma):

And he act bi-sexual. He act gay. No offense to anyone, but he really didn’t get into how he got it but I’m thinking, you know, by [being] gay or him just being bi-sexual would put him at risk. (PLWHA participant)

Felt normative stigma and lack of disclosure are related consequences of HIV stigma for PLWHA in the following quotation example:

And it was always the same story. People would rather die and cover it up [HIV/AIDS] than to expose themselves to ridicule, ‘cause there’s nobody to actually counsel them. (PLWHA participant)

Lack of disclosure could also be directly affected by causes of HIV stigma, such as lack of knowledge about HIV among loved ones within the community:

My family and friends and my church family because they’re, like I said, unknowledgeable of it [HIV/AIDS] so I keep it hid…I would let whoever know not to bring it up around my family or whoever because they…it’s lack of knowledge of it. (PLWHA participant)

Since the first phase of our project was to understand the feasibility of implementing HIV clinical trials in rural communities—using either a standing clinic or mobile unit—some of our questions focused on what may make it difficult to implement clinical trials locally. The themes elicited from this inquiry were considered to be more reflective of the consequences of HIV stigma and associated with non-disclosure. As an example, the following quotation illustrates the concern over protecting confidentiality when using a mobile van to conduct HIV clinical trials:

I guess it would be okay for people if they really didn’t mind people knowing what was going on. ‘Cause I don’t see how, I mean to me that’s going back to confidentiality. I mean if there’s a van parked somewhere…I could hear people now, “what is that van for?” or “why you going to that van?” And so it’s just like you’re opening yourself up. So me personally, I wouldn’t [go]. (PLWHA participant)

A community leader focus group participant echoed similar issues with using a mobile van:

Once it comes in once or twice…people are going to know the van…And then if they know oh that’s [the] AIDS [van] well…“Why is he getting in that? He must have AIDS. Let’s go tell the neighbors.”

For some, local implementation of HIV clinical trials may not be feasible because of potential breaches in confidentiality. When asked about their preferences of where to go to participate in HIV clinical trials, a PLWHA participant stated:

I would prefer to go to University [A] ‘cause I wouldn’t want to participate in nothing in my own, oh no, not in my own community, no sir…Because folks talk so much and ohhh, I could see my name around, oh no…I would go out of town where nobody didn’t know me…And then I wouldn’t have to worry about it being exposed.

Not reflected in Figure 1, but important because it identifies countering strategies, community leaders, providers, and PLWHA identified some ways in which HIV stigma could be addressed and combated should HIV clinical trials be implemented locally in rural communities. The following examples were elicited from a question asking about views of a mobile van as a mechanism to conduct HIV clinical trials locally:

PLWHA: Testing. I think it [mobile van] should do blood pressure. I think it should do a lot of other things because then that way people won’t stay focused just on HIV…if they do other testing it would make it justified for me to walk up to the van and get some pills from you or, or get a box from you and say I went and got tested…And it wouldn’t mean so much exposure…

Providers: Just a fear of people finding out that van’s parked there and what it’s here for, ‘cause it won’t take long. That’s why I said if you do it with other services…You could bundle the services…Like medical…or wellness screening…You’ve got to say something different than say, ‘hey I’m the HIV bus.’

Community leaders: The community as a whole doesn’t even know what the true purpose of that van is…You really have to camouflage…It has an ulterior motive and you also have to have an underground mode of communications for the people that you want to get in, to go to it…so there’s no stigma attached.

Discussion

Although the multifaceted concept of HIV stigma is not new in the field of HIV/AIDS, we never expected the problem of HIV stigma to still be so prominent in US communities in the 21st century. Using existing theoretical constructs, we explored the types of HIV stigma evident in rural, minority communities of North Carolina, but this is the first study to use the guided framework to develop a conceptual model exploring HIV stigma and its potential impact on HIV clinical trial implementation in rural communities. In general, the guided theoretical framework was useful in classifying HIV stigma themes under the constructs of perceived stigma, experienced stigma, vicarious stigma, and felt normative stigma. It was not clear, however, if some of the HIV stigma themes—specifically those from PLWHA interviews—could have been classified under internalized stigma given that their expression in the textual data did not necessarily reflect PLWHA self-blame or their agreement with the negative attitudes the community may have had about them. We did not consider internalized stigma to be a problem a priori and, for this reason, did not ask PLWHA with follow-up probes if they agreed or believed in some of the stigmatizing views reported in their communities. This could be considered a study limitation given that it would be important to understand the extent of internalized stigma in the community for the purposes of targeted stigma reduction interventions at the PLWHA level.

The relationships among perceived stigma, experienced stigma, vicarious stigma, and felt normative stigma were significant. In our conceptual model, we were hypothesizing that felt normative stigma was more of a consequence of the other HIV constructs (perceived stigma, experienced stigma, vicarious stigma), thus creating possible scenarios where PLWHA are passing as persons who are not infected or have some other non-stigmatized disease (e.g., if PLWHA have significant weight loss, they tell their community they have cancer). Felt normative stigma also has implications for local HIV clinical trial implementation because there is a great deal of fear among PLWHA surrounding how to protect the confidentiality of their HIV status from the community. Using a mobile van to conduct clinical trials engendered several concerns relating to how PLWHA, who might benefit from clinical trials, do so without their community finding out they are HIV positive. The next stage of this research will tackle the feasibility of mobile vans or stand-alone clinics as possible mechanisms to conduct HIV clinical trials in rural settings.

While the existing theoretical constructs were useful to classify some of our HIV stigma themes, we could not use this approach with all of our stigma-related themes, particularly the themes that arose from asking the questions about community/personal views on HIV/AIDS and the difficulties of implementing HIV clinical trials locally. For the themes elicited from the community/personal views on HIV/AIDS, we classified the majority as causes of HIV stigma because we felt that issues relating to lack of HIV/AIDS education, or denial that HIV is a problem, do not represent HIV stigma examples by themselves, but have been shown to be associated with HIV stigma.14,15 We hypothesized, however, that people not getting HIV testing could be a consequence of HIV stigma. Similarly, lack of disclosure to the community, family, or friends, or the issues of confidentiality relating to HIV clinical trials participation were classified as consequences given that these themes do not, by themselves, represent HIV stigma. It is important to address these confidentiality concerns as a component of any intervention that we develop since they have implications for the willingness of PLWHA to participate in local HIV clinical trials, and broader implications for the elimination of health care disparities in HIV care access.

Lastly, the ultimate goal in our project is to develop a mechanism (e.g., mobile van) for conducting HIV clinical trials in local, rural communities. To overcome the issue of possible breaches in confidentiality, both PLWHA and focus group participants advocated going to great lengths to hide or mask clinical trials with other types of services. Thus, if we were to take this recommendation, we could offer a combination of health care services, including HIV clinical trials, on a mobile unit or within a stand-alone clinic, as a means to protect confidentiality of individuals who are seeking HIV clinical trial services. The purposeful masking of HIV services could be a potential problem from a research ethics standpoint, but we would adhere to the principles underlying research integrity and ethics to make implementing local HIV clinical trials a viable option.

As with all studies, this study has its limitations. While we were interested in determining if there were racial/ethnic differences in the feasibility of conducting HIV clinical trials in rural communities, the textual data from the Latino participants (either from one focus group or the four individual interviews) did not suggest any relationships between HIV stigma and HIV clinical trials. Rather, other barriers to HIV clinical participation for Latino PLWHA were elicited that included being undocumented immigrants and separated from their families, dual issues that generally can affect accessing health services for Latinos in the US16 but did not co-occur with our HIV stigma themes. It is possible that, given our very small subsets of Latino participants, we were not able to capture these data with the interview guide questions we asked.

Another study limitation has to do with generalizeability. HIV stigma demonstrated in these communities in rural North Carolina may be comparable to HIV stigma in other southeastern communities, but this cannot be assumed from these findings. It does appear, however, that HIV stigma in rural North Carolina may be higher than what is reported in US metropolitan areas, particularly for men who have sex with men.17 Furthermore, we found that the pervasiveness of HIV stigma is uncannily similar to that reported in China or other relatively resource-poor countries/regions in the world.9,18–20 Future research is warranted to apply our conceptual model to other demographically similar rural US communities, as well as distinctly different communities in the US and other nations as a way to increase the external validity of the HIV stigma themes identified in this study.

HIV stigma continues to be a daunting challenge in US rural communities that seek to bridge the gap in health disparities and access to care, including making HIV clinical trials accessible. Nevertheless, our study findings suggest that efforts to address HIV stigma in rural US settings may be crucial if health disparities are to be addressed. The conceptual model developed will be useful for planning, developing, and implementing HIV stigma reduction interventions at the community and individual levels.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Sengupta led the team that analyzed the data. The team included Dr. Miles, Dr. Roman-Isler, and Ms. Banks. In addition, we would like to acknowledge Michelle Hayes, Joiaisha Bland, and Jeffery Edwards for their contributions to data collection and data analysis.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, Grant # R01NR010204-01A2; UNC GCRC, Grant # RR00046; and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Grant # K01AI055247-05.

Footnotes

Data presented: XVII International AIDS Society Conference in Mexico City, August 7, 2008.

Contributor Information

Sohini Sengupta, assistant professor in the Department of Social Medicine in the School of Medicine, and research coordinator with the Center for Faculty Excellence at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She can be reached at sengups (at) unc.edu.

Ronald P. Strauss, executive associate provost and professor in the School of Dentistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Margaret S. Miles, professor emeritus in the School of Nursing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Malika Roman-Isler, assistant director of the Community Engagement Core in the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute (NC TraCS) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Bahby Banks, research assistant at the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Giselle Corbie-Smith, associate professor in the Department of Social Medicine, a senior research fellow at the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, an associate professor in the Department of Medicine, and an associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology in the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whetten K, Reif S. Overview: HIV/AIDS in the deep south region of the United States. AIDS Care. 2006;18 suppl 1:S1–S5. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reif S, Geonnotti KL, Whetten K. HIV infection and AIDS in the deep south. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):970–973. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.North Carolina Division of Public Health, HIV/STD Prevention and Care Branch. [Accessed May 25, 2009];HIV/STD Surveillance Report. 2007 http://www.epi.state.nc.us/epi/hiv/pdf/std07rpt.pdf.

- 4.Nyblade LC. Measuring HIV stigma: existing knowledge and gaps. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):335–345. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahendra VS, Gilborn L, Bharat S, et al. Understanding and measuring AIDS-related stigma in health care settings: a developing country perspective. Sahara J. 2007;4(2):616–625. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2007.9724883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinsler JJ, Wong MD, Sayles JN, Davis C, Cunningham WE. The effect of perceived stigma from a health care provider on access to care among a low-income HIV-positive population. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(8):584–592. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konkle-Parker DJ, Erlen JA, Dubbert PM. Barriers and facilitators to medication adherence in a southern minority population with HIV disease. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19(2):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King WD, Defreitas D, Smith K, et al. Underrepresented Populations Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG). Attitudes and perceptions of AIDS clinical trials group site coordinators on HIV clinical trial recruitment and retention: a descriptive study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(8):551–563. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institutes of Health. NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research—amended. [Accessed May 25, 2009];2001 October; http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines_amended_10_2001.htm.

- 10.Steward WT, Herek GM, Ramakrishna J, et al. HIV-related stigma: adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(8):1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricketts TC, Johnson-Webb KD, Taylor P. Definitions of Rural: A Handbook for Health Policy Makers and Researchers. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowen GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qual Res. 2008;8(1):137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genberg BL, Hlavka Z, Konda KA, et al. A comparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2279–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visser MJ, Makin JD, Vandormael A, Sikkema KJ, Forsyth BW. HIV/AIDS stigma in a South African community. AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):197–206. doi: 10.1080/09540120801932157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortega AN, Fang H, Perez VH, et al. Health care access, use of services, and experiences among undocumented Mexicans and other Latinos. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(21):2354–2360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preston DB, D’Augelli AR, Kassab CD, Starks MT. The relationship of stigma to the sexual risk behavior of rural men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(3):218–230. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holzemer WL, Uys L, Makoae L, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(6):541–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Hu Z, Li X, Stanton B, Naar-King S, Yang H. Understanding interrelationships among HIV-related stigma, concern about HIV infection, and intent to disclose HIV serostatus: a pretest-posttest study in a rural area of eastern China. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(2):133–142. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]