Abstract

Deposition of amyloid fibrils, consisting primarily of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides, in the extracellular space in the brain is a major characteristic of Alzheimer's disease (AD). We recently developed new (to our knowledge) drug candidates for AD that inhibit the fibril formation of Aβ peptides and eliminate their neurotoxicity. We performed all-atom molecular-dynamics simulations on the Aβ42 monomer at its α-helical conformation and a pentamer fibril fragment of Aβ42 peptide with or without LRL and fluorene series compounds to investigate the mechanism of inhibition. The results show that the active drug candidates, LRL22 (EC50 = 0.734 μM) and K162 (EC50 = 0.080 μM), stabilize hydrophobic core I of Aβ42 peptide (residues 17–21) to its α-helical conformation by interacting specifically in this region. The nonactive drug candidates, LRL27 (EC50 > 10 μM) and K182 (EC50 > 5 μM), have little to no similar effect. This explains the different behavior of the drug candidates in experiments. Of more importance, this phenomenon indicates that hydrophobic core I of the Aβ42 peptide plays a major mechanistic role in the formation of amyloid fibrils, and paves the way for the development of new drugs against AD.

Introduction

Many human diseases, including amyloidoses and some neurodegenerative diseases, have been related to the conformational change of a protein or a protein fragment from its native structure into insoluble fibrils (1–3). Among these, Alzheimer's disease (AD) is considered to be the most prevalent form of age-dependent dementia. Its major characteristic is the deposition of stable, ordered, filamentous aggregates in the brain, which are commonly known as amyloid fibrils. These fibrils consist primarily of 40- and 42-residue amyloid β (Aβ) proteins, which are the endoproteolytic cleavage product of the amyloid β-protein precursor (AβPP) (4). Like many other amyloid fibrils, the Aβ fibrils assume cross β-pattern structures (5).

Researchers have been investigating the properties and causes of AD for approximately a century (6). The aggregation of Aβ proteins is considered to play an essential role in the pathogenesis of AD (7–14). It was recently found that the neurotoxicity of AD is the result of soluble oligomers and fibril intermediates (protofibrils) (15, 16), and is more strongly correlated with aggregative ability than secondary structure (17).

To date, the cause of amyloid fibril formation in vivo is not completely clear. In vitro agitation and/or the presence of preformed fibers have been found to promote fibril formation. Aβ proteins are believed to be unstructured in aqueous solution in the absence of organic molecules (18). However, in the presence of tetrafluoroethylene or sodium dodecyl sulfate (conditions thought to mimic the membrane-associated Aβ proteins in the cellular environment), Aβ proteins adopt predominantly α-helical conformations (19, 20). It is believed that, starting from monomers, Aβ proteins first undergo conformational changes and self-assemble into soluble oligomers that eventually aggregate to form insoluble fibrils. Circular dichroism spectroscopy experiments at pH 7.5 and 22°C in aqueous solution indicated that the intermediates in amyloid fibril formation are mainly unfolded, and an increase in α-helix content during the fibrillogenesis of Aβ proteins was followed by a rapid increase in β conformation (21). Thus, stabilization of the α-helix conformation may help to inhibit amyloid fibril formation.

Aβ42 (DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVVIA) is a 42-residue protein. The Aβ40 variant is shorter because it is missing two hydrophobic amino acids (Ile and Ala) at the C-terminus, and thus is less prone to aggregate (22,23). Earlier molecular-dynamics (MD) simulation studies showed that Aβ10-35 has no clear structural preference in aqueous solutions (24). Further studies revealed a stable hydrophobic core LVFFA (17–21) and a VGSN (24–27) β-turn that is stabilized by the salt bridge between D23 and K28 (25). Recent studies on truncated Aβ proteins indicated that residues 17–21 and 30–35 are the important regions for promoting Aβ aggregation and are responsible for the neurotoxicity because of their high propensity to aggregate (17,26).

Two main approaches are used for the development of AD drugs (6). One is to modulate the processing of AβPP and the production and clearance of Aβ proteins. The other is to directly inhibit the amyloid formation of Aβ proteins. The latter process has gone through two different stages. Initially, investigators focused on developing drugs that could inhibit fibril formation, and mainly used the Aβ40 protein as the target. Recently, however, it was discovered that amyloid fibrils are formed through oligomeric Aβ assembly intermediates, which are more toxic than the polymeric fibrils. Also the Aβ42 protein goes through a different oligomeric process than Aβ40 proteins, in which protofibril-type oligomers are formed. This more-amyloidogenic character makes Aβ42 more neurotoxic than Aβ40 (15,16). Therefore, the second, ongoing stage of drug discovery for AD is focused on how to inhibit oligomer formation using Aβ42 as the target. Currently, two main strategies are used to look for potential drugs. One is to use structural similarities and aromatic interactions to look for small peptides or polymers, such as polyphenols (27) and compounds composed of a molecular recognition element (KLVFF) (28), that can bind to the β-sheet to inhibit the formation of aggregates. The other approach is to stabilize the monomer native conformation of Aβ proteins to prevent fibril formation. Examples of this approach include the utilization of the inhibitive effect of inorganic phosphate when it binds to the native structure of Aβ proteins (29), and a derivative of ferulic acid and styryl benzene that has been shown to bind to nonfibrous monomer-like Aβ42 (30). Recently, Nerelius et al. (31) showed that ligands that specifically bind to the region of residues 13–26 of the Aβ protein are able to stabilize the helical conformation and reduce polymerization and toxicity in vitro and in vivo.

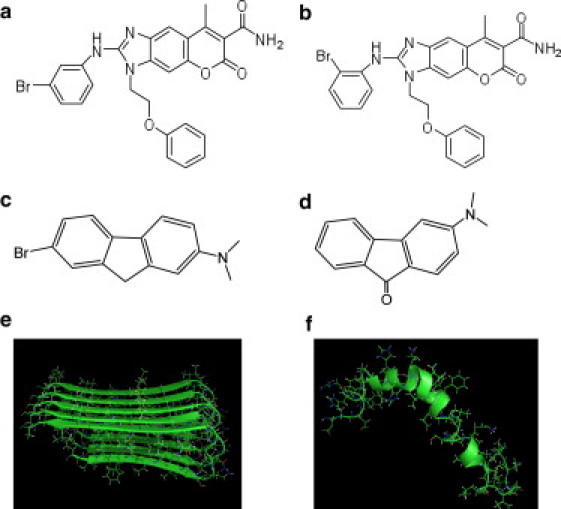

Investigators have recently discovered a series of promising active compounds from 9366 compounds of 10 combinatorial libraries by using high-throughput, cell-based assays. These active compounds are able to inhibit the formation of amyloid oligomers and fibrils, and reduce their neurotoxicity. Some of these compounds can also pass the blood-brain barrier, making them potential drug candidates for AD. The four compounds we studied belong to two different series: the LRL series (H. S. Hong, R. Liu, K. S. Lam, and L. W. Jin, unpublished) and the fluorene series (33) (see Fig. 1, a–d). Compound LRL22 is an active drug candidate against AD in vitro. It is able to pass the blood-brain barrier and has an EC50 value of 0.734 μM. Compound LRL27 is very similar in structure to LRL22, with a slight difference in the bromine atom position. However, LRL27 is nonactive in vitro, with EC50 > 10 μM. The fluorene series compounds are termed K162 and K182. K162 is significantly more potent, with an EC50 of 0.080 μM, and K182 has an EC50 > 5.0 μM. The high degree of similarity within each series of compounds and the notably different activities present an interesting subject to study. Our goal in this work was to understand what causes these differences, and to shed some light on the future development of AD drugs.

Figure 1.

Structures of the compounds studied in this work: (a) LRL22, (b) LRL27, (c) K162, and (d) K182. (e) NMR structure of Aβ42 pentamer. (f) NMR structure of Aβ42 monomer.

Materials and Methods

The focus of this study is to show how the above-described compounds influence the Aβ42 protein and its oligomers. Each system includes the Aβ42 monomer, which has an initial structure in α-helix form, and four molecules of one drug compound that are placed randomly around the monomer at a minimum distance of 10 Å to allow the peptide to relax and sample other conformations. A helical conformation (PDB code 1Z0Q (34) (Fig. 1 f) was chosen for the initial structure of Aβ42 monomer in our simulation. For the purpose of comparison, we also carried out simulations in the absence of any compound. We conducted four simulations of 80 ns for each system, using the same initial structure but different velocities, and choosing different random numbers of seeds.

We included results from simulations of Aβ oligomer in the presence of drug compounds. Because it is difficult to detect the Aβ oligomer directly, to date there is no consensus regarding its structure (35). In a study using high-resolution atomic force microscopy, Mastrangelo et al. (36) proposed that low-weight oligomers are in fact structured and their topology is very similar to that observed in mature fibrils. On the basis of this finding, we chose an NMR structure of a pentamer in AD fibrils (PDB code 2BEG (5)) as a model of soluble low-weight oligomers (Fig. 1 e). This pentamer is constructed by five β hairpins stacked together by backbone hydrogen bonds. Each β hairpin includes residues 17–42 of Aβ42 protein because the N-terminal is not structured. Each system consists of one Aβ42 pentamer and five molecules of one drug compound that are placed randomly around the oligomer at a minimum distance of 10 Å. Please note that the model we chose for Aβ oligomer is not meant to represent all possible forms of oligomers. Our intention is solely to provide some type of comparison of the effects of drug compounds on Aβ monomers and oligomers.

The AMBER software package (37,38) was used for both the MD simulations and data processing. Proteins were represented using the AMBER FF03 force field. The drug compounds were represented using the AMBER generalized force field (39) for organic molecules. The structures of drug compounds were built using GaussView (40) and optimized at HF/6-31G∗ level of theory to obtain the initial structures for dynamics studies and for charge fitting. Partial charges for the drug compounds were fitted to the electrostatic potential at HF/6-31G∗∗ level of theory.

During the MD simulations, all systems were subjected to periodic boundary conditions via both minimum image and discrete Fourier transform as part of the particle-mesh Ewald method (41). The systems were then immersed into a TIP3P (42) Octahedron box. The dimensions of the box were chosen to ensure that there would be a 12.0 Å distance between the protein-compound complex and the edge of the box. The systems were then subjected to a two-step minimization. First, the protein-compound complexes were fixed to minimize the water molecules for 4000 steps. Then the complete systems were minimized without any restrain for 20,000 steps. After minimization was completed, MD simulations were performed under NPT conditions using the PMEMD (43) program in Amber package. The first 200 ps were used to equilibrate the system to adjust the system size and density. We then conducted 80 ns simulations at 300 K in the NPT ensemble with a step size of 2 fs. The particle-mesh Ewald (41) method was used to treat the long-distance interactions. SHAKE (44) was applied to constrain all covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms. Temperature was controlled at 300 K by means of Andersen's algorithm (45). The center-of-mass translation and rotation were removed every 500 steps, because studies have shown that this removes the block-of-ice problem (46,47). The trajectories were saved at 2.0 ps intervals for further analysis. All molecules that were present in the simulations were subjected to analysis. All analyses of the Aβ protein were done for the last 20 ns of each simulation run.

Results and Discussion

Interaction between the Aβ monomer and the drug candidates

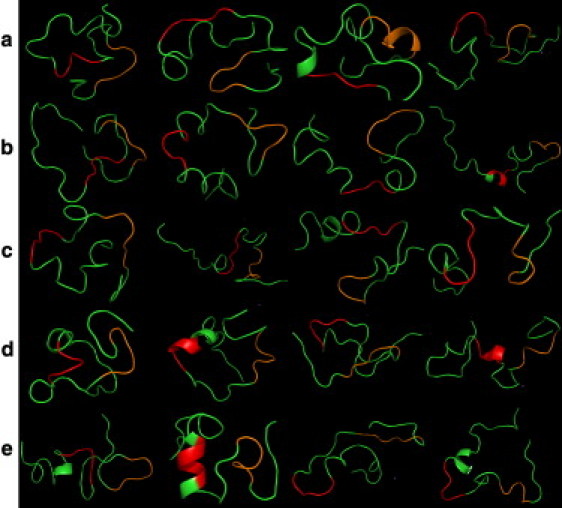

We carried out simulations to investigate the effect of each compound on the Aβ42 monomer. The systems were started with the monomer at its α-helical conformation as seen in the NMR structure (PDB code 1Z0Q (34)). Four molecules of one drug compound were initially randomly positioned 10 Å away from the monomer. Four trajectories of 80 ns were carried out for each compound-Aβ42 monomer mixture, resulying in a total of 320 ns of simulation for each system. We used the last 20 ns of simulation of each trajectory to perform the clustering analysis to identify the substrates sampled during the simulations. The segment of residue 13–35 was used for the clustering because the N- and C-terminals are unstructured in water (34). The four most populated clusters for each system are shown in Fig. 2, in which hydrophobic core I, consisting of residues 17–21 is shown in red, and hydrophobic core II, consisting residues 30–35, is shown in orange. These four clusters account for ∼98% of the snapshots in each system.

Figure 2.

The four most populated clusters for each system: (a) Aβ42 protein alone, (b) Aβ42 protein with compound LRL22, (c) Aβ42 protein with compound LRL27, (d) Aβ42 protein with compound K162, and (e) Aβ42 protein with compound K182. The red color represents the hydrophobic core I from residue 17 to residue 21, and orange represents the hydrophobic core II from residue 30 to residue 35.

The Aβ42 monomer alone (without the compounds) mainly adopts a random coil with little helix sediment (Fig. 2 a). This observation is consistent with previous experimental and theoretical results (18). In the presence of compounds, the behavior of the Aβ protein can be categorized into two groups. In the presence of LRL22, K162, or K182, the Aβ protein is able to retain partial helical conformation in the hydrophobic core I region (Fig. 2, b–d). These three compounds have different degrees of activity toward the amyloid fibrils in experiments, with EC50 = 0.734 μM, 0.080 μM, and >5 μM, respectively. In contrast, when LRL27 is present, the Aβ protein retains very little helical conformation, particularly in the hydrophobic core I region. None of the drug compounds showed a significant effect in stabilizing the hydrophobic core II region.

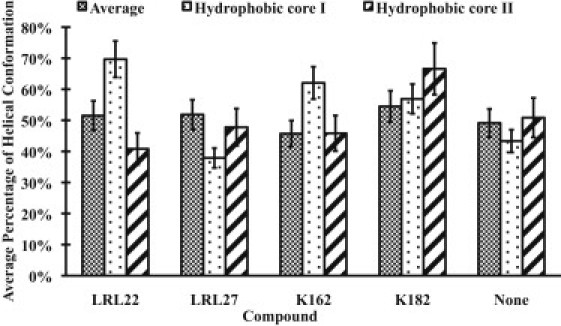

We calculated the average percentage time in the last 20 ns of the simulations of the residues in the helical conformation for the complete peptide chain and the two hydrophobic core regions (Fig. 3). The quantities plotted in Fig. 3 are calculated from the percentage of the backbone ϕψ angle that falls in the Ramanchandran helical region, and averaged over the residues. As shown in Fig. 3, in terms of average percentage time for adopting the helical conformation, the five different systems are similar when the entire protein is considered. Therefore, the efficiency of a compound against AD is not related to this property. However, notable differences can be observed in the hydrophobic core I region (residues 17–21). Specifically, in the presence of the compounds (LRL22, K162, and K182), the helicity is clearly increased by 60%, 43%, and 31%, respectively, compared with that observed in the protein alone. In contrast, in the presence of the compound (LRL27), the helicity is decreased by 13%. This observation is consistent with the experimental finding that residues 17–21 (LVFFAE) play a crucial role in the neurotoxicity and formation of amyloid fibrils (17,26). Although the hydrophobic core II region (residues 30–35) has also been suggested to play an important role in Aβ aggregation (17), there is no consensus regarding the influence of the drug compounds in this region.

Figure 3.

Average percentage of adopting a helical conformation for the complete protein chain and the hydrophobic core I (residues 17–21) and hydrophobic core II (residues 30–35) regions.

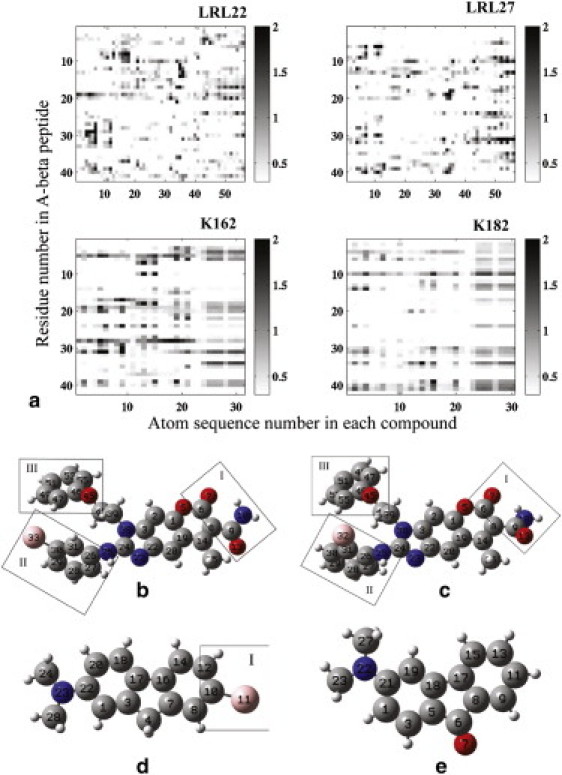

We calculated the interaction maps between each amino acid in Aβ42 protein and each compound molecule (Fig. 4). An interaction was defined as one in which the distance between two atoms was within the 3.5 Å range. If any atom on an amino acid contacted any atom of the compound molecule, the corresponding amino acid was considered to have one contact with the compound. In Fig. 4, a, interactions between the two LRL series compounds and Aβ42 protein are preferentially in two regions of the protein: hydrophobic cores I (residues 17–20) and II (residues 30–35). These two compounds show comparable patterns in binding to Aβ42 monomer. In Fig. 4, a, it is clear that K162 interacts with the protein in the region of hydrophobic core I to a greater degree. At the same time, it has interactions both downstream and upstream of this region, which may contribute to its ability to stabilize the helical conformation in the hydrophobic core I region in Aβ42 protein. Region I of the K162 compound plays the most important role in this strong interaction between the compound and the protein. K182 interacts with the protein in a more extended area but in a much weaker mode, especially in the hydrophobic core I region; however, there is no particular fragment of K182 that interacts with the protein more than the rest. K182’s lack of specificity most likely contributes to its being a notably weaker compound than K162. Snapshots shown in Fig. S1 of the Supporting Material illustrate the interactions in the first four populated clusters and provide a consistent view of the interacting modes between each compound and Aβ42 monomer.

Figure 4.

(a) Map of interactions between each compound and the Aβ42 monomer. The horizontal axis is the sequence number of the atoms in each compound, and the vertical axis is the residue number in the Aβ42 peptide. The corresponding compounds are (b) LRL22, (c) LRL27, (d) K162, and (e) K182. Carbons are in gray, oxygens are in red, nitrogens are in blue, bromines are in pink, and hydrogens are in white. The interaction map layout corresponds to the compound layout below it.

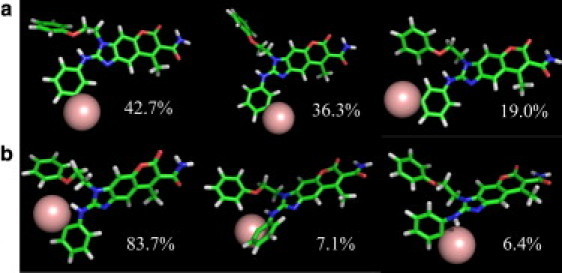

The LRL22 and LRL27 compounds are structurally very similar to each other, but they behave differently when they interact with the protein. To investigate this issue, we performed a cluster analysis on the conformations of these two compounds using the heavy atoms in regions II and III (labeled in Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 5, the most populated clusters of LRL22, which account for 98% of the conformational space, have structures in which the two rings are flexible enough to adopt more conformations and do not form an intramolecular hydrogen bond. In contrast, LRL27 mainly adopts a conformation in which the bromine atom in region III forms contact with the region II benzene ring. This conformation causes the two rings to be closer to each other and likely more rigid. As a result, the bromine atom has less chance to interact with the protein.

Figure 5.

The three most populated clusters adopted by (a) LRL22 and (b) LRL27 during the simulations.

Interaction between the Aβ oligomer and the drug candidates

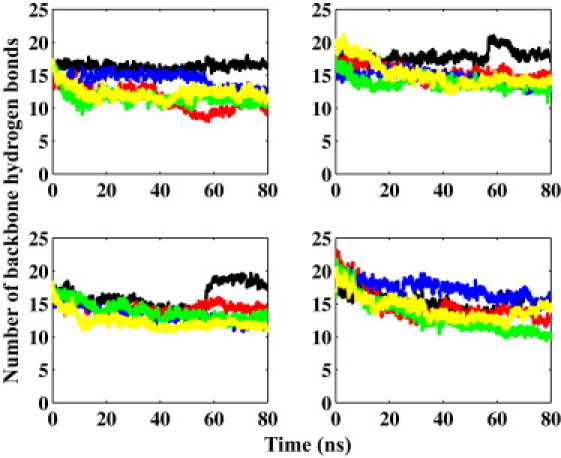

We carried out four sets of simulations to study the effects of each organic compound on the oligomer. We also performed simulations on the Aβ oligomer alone to assess its stability in water and use it as a control for the other four systems. In an oligomer, the most important feature is the backbone hydrogen bonds between the neighboring β hairpins. There are four interstrand backbone hydrogen bond groups in a pentamer. We calculated the average number of interstrand hydrogen bonds between the adjacent strands (Fig. 6). In the absence of the compounds, the number of backbone hydrogen bonds did not decrease significantly during the simulation. This suggests that the oligomer is reasonably stable in aqueous solution without the compounds. This was consistent in all four interstrand backbone hydrogen bond groups. In the presence of any of the four compounds, the first three groups of backbone hydrogen bonds were reduced, but by only a small number (<30%) compared with the oligomer alone. Backbone hydrogen bonds in the fourth group behaved more similarly to those in the oligomer alone without the organic compounds. Of more importance, all four compounds exhibited a similar effect on the oligomer, in that the stable oligomer structure was only slightly more disturbed when any of the four compounds was present. Maps of the interactions between each compound and Aβ oligomer are shown in Fig. S3. The interactions were broken down to the compound and individual β strand. The definition of an interaction was the same as used for the interaction map between the compounds and Aβ42 monomer. All compounds showed a slight preference to interact with the β-strand regions of the oligomer as opposed to the turn regions. However, there was no significant difference from one compound to another. This is consistent with the result that all compounds had a similar effect on the structure of the Aβ oligomer.

Figure 6.

The number of backbone hydrogen bonds between the neighboring β hairpins in oligomer with LRL22 (red), LRL27 (blue), K162 (green), K182 (yellow), and without any compound (black). From left to right and top to bottom are respectively hydrogen bonds between the first and second, second and third, third and fourth, and fourth and fifth β hairpins.

As noted above, our results regarding interactions between the drug compounds and the Aβ oligomer are limited by the fact that a consensus on the structure of Aβ oligomer has not been established. Our results showed only one special case in which the Aβ oligomer had a cross-β-pattern structure. Future discoveries about the Aβ oligomer structure are essential to provide a more solid foundation for studying the interaction between drug candidates and the Aβ oligomer, as well as for setting the direction for next-generation drug design.

Binding free energy between the drug compounds and Aβ

The binding free energy between Aβ and the drug compounds is not clearly defined, given the above finding that they interact with each other in a more stochastic fashion than do proteins and ligands. We estimated the binding free energy of the drug compounds to Aβ oligomer or monomer by performing molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) calculations (48) on snapshots taken every 0.5 ns from the simulation. Because the MD simulations were run with more than one drug compound molecule present, each snapshot generates a corresponding number of Aβ-drug complexes, among which the Aβ conformation is identical and the drug compounds sample different orientations. Therefore, the conformations are sampled in terms of both Aβ and the drug compounds. The energies are plotted with respect to the minimum distance from the center of mass of the drug compounds to Aβ (Fig. S2) for each complex. The bounded state is considered to have a distance of <8.0 Å, and the unbounded state has a distance of >15.0 Å. The results are shown in Table 1. For comparison, the experimental measurement of the EC50 data is also shown.

Table 1.

Binding free energies of drug-Aβ monomer and drug-Aβ oligomer

| LRL22 (H. S. Hong, R. Liu, K. S. Lam, and L. W. Jin, unpublished) |

LRL27 (32) |

K162 (33) |

K182 (33) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro EC50 (μM) | 0.734 | >10 | 0.080 | >5.0 | |

| Oligomer | Average | −18.8 | −19.3 | −10.2 | −16.9 |

| Minimum | −68.0 | −70.3 | −52.9 | −52.8 | |

| Monomer | Average | −20.8 | −24.2 | −10.4 | −19.5 |

| Minimum | −80.8 | −63.1 | −55.5 | −74.0 | |

The free energies were calculated using the MM/GBSA method. The average energies are the differences between the total energies averaged over the structures that belong to the bound and free states. The minimum energies are the lowest binding free energies between the states. Energies are in units of kcal/mol.

For the Aβ oligomer, the binding free energies are similar between LRL22 and LRL27. The two K-series compounds exhibit a notable difference in their binding free energies, with K182 more favorable than K162 by ∼6.6 kcal/mole.

In the case of Aβ monomer, the binding free energies calculated by average are similar for LRL22 and LRL27, with LRL27 binding more favorably by 3.3 kcal/mole. Using the minimum binding energies for the bound and unbound states, LRL22 displays significantly stronger binding energy by 17.7 kcal/mol. This, combined with its preferential interaction in the hydrophobic core I region (residues 17–21), contributes to its better efficiency in the experiment. Although K182 exhibits better binding energy than K162 using both methods, K182 is less efficient than K162 in the experiment. Because K182 demonstrated no specificity in interacting with Aβ in the hydrophobic core I region, we conclude that this strong binding energy is mainly due to interactions that have no effect in stabilizing the helical conformation in the hydrophobic core I region. This result further indicates that the specificity in interaction toward the hydrophobic core I region (residues 17–21) is an essential factor in designing efficient inhibitors of AD.

The binding free energies of drug-Aβ oligomer and drug-Aβ monomer measure the tendency of the drug to form complexes with Aβ. The Aβ oligomers are considerably more stable than the monomers because they benefit from the backbone hydrogen bonds and side-chain hydrophobic interactions. It is likely that substantially larger energy contributions would be required to disrupt the structure of Aβ oligomers, necessitating a higher concentration of drug compounds or an intrinsically stronger interaction energy for the Aβ oligomer. Given the possible toxicity of a drug compound at high concentration, an ideal strategy for designing effective inhibitors of AD would be to induce specific and strong binding to the hydrophobic core I region (residues 17–21) to stabilize the Aβ monomer, as well as a strong binding to the Aβ oligomer to disassemble it.

Conclusions

In this work, we carried out simulations on oligomers with and without the presence of compounds. Considering the special structural property of the oligomers, we focused our analysis on the number of backbone hydrogen bonds between two neighbor β hairpins. In the system of the oligomer alone, the numbers of backbone hydrogen bonds did not decrease by much, which suggests that the oligomer structure is considerably stable in aqueous solution. All four compounds had similar effect on the oligomer, in that the stable oligomer structure was only slightly disturbed when any of the four compounds were present. We note that because of the lack of information on the Aβ oligomer, this conclusion is biased. More structural information is necessary to generate a complete picture.

Our simulations on the Aβ42 monomer show that the monomeric Aβ42 protein in water is mainly disordered, which is in agreement with a previous study (18). An active compound is able to help the Aβ42 protein retain a partial helical conformation. In particular, the helix segment coincided with hydrophobic core I (residues 17–21). The more efficient drug compounds interact with the Aβ42 monomer strongly in the hydrophobic core I region. The less active compounds might also be able to help the Aβ protein maintain a certain degree of helical conformation. However, interactions between a less active drug compound and the Aβ42 monomer were notably weaker in terms of either lower binding energy or a lack of preference for the area of interaction. Of more interest, although the protein does not have a folded structure, some compounds were able to interact with it in a specific area. This is in contrast to the normal concept of drug docking in proteins, and it makes the approach that was used to discover the active compounds in this work promising for future attempts to design drugs for AD.

The location of the bromine atom also plays an important role in interactions between the compounds and the protein. The only difference between LRL22 and LRL27 is the position of the bromine atom on the benzene ring. In LRL27, the bromine is able to form intramolecular contact with another benzene ring nearby, which leads to rigidity of the structure and loss of the effect of the bromine on the protein. Although in LRL22, the bromine atom is less likely to form intramolecular contacts. As a result, the two benzene rings are free to move around, which leads to better interactions with the protein and especially the bromine atom. The structures of the two fluorene series compounds are also similar, but to a lesser degree. It seems that the different electronegativity of oxygen from bromine leads to varied binding energy to Aβ and, more importantly, to distinct binding sites.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM67168 and GM79383 to Y.D.) and a UCD Health System Research Award to R.L. Computing time was provided by Teragrid (TM-MCA06N028).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Dobson C.M. Protein misfolding, evolution and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson C.M. The structural basis of protein folding and its links with human disease. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2001;356:133–145. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rochet J.C., Lansbury P.T., Jr. Amyloid fibrillogenesis: themes and variations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:60–68. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang R., Sweeney D., Sisodia S.S. The profile of soluble amyloid β protein in cultured cell media. Detection and quantification of amyloid β protein and variants by immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:31894–31902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lührs T., Ritter C., Riek R. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-β (1-42) fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberson E.D., Mucke L. 100 years and counting: prospects for defeating Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2006;314:781–784. doi: 10.1126/science.1132813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D.S., Dickson D.W., Malter J.S. β-Amyloid degradation and Alzheimer's disease. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2006;2006:58406. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/58406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowther D.C., Kinghorn K.J., Lomas D.A. Intraneuronal A β, non-amyloid aggregates and neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 2005;132:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cataldo A.M., Petanceska S., Nixon R.A. Aβ localization in abnormal endosomes: association with earliest Aβ elevations in AD and Down syndrome. Neurobiol. Aging. 2004;25:1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeuchi T., Dolios G., Sisodia S.S. Familial Alzheimer disease-linked presenilin 1 variants enhance production of both Aβ 1-40 and Aβ 1-42 peptides that are only partially sensitive to a potent aspartyl protease transition state inhibitor of “γ-secretase”. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7010–7018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Jonghe C., Zehr C., Eckman C.B. Flemish and Dutch mutations in amyloid β precursor protein have different effects on amyloid β secretion. Neurobiol. Dis. 1998;5:281–286. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomita T., Tokuhiro S., Iwatsubo T. Molecular dissection of domains in mutant presenilin 2 that mediate overproduction of amyloidogenic forms of amyloid β peptides. Inability of truncated forms of PS2 with familial Alzheimer's disease mutation to increase secretion of Aβ42. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:21153–21160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson-Wood K., Lee M., McConlogue L. Amyloid precursor protein processing and A β (42) deposition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:1550–1555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teller J.K., Russo C., Gambetti P. Presence of soluble amyloid β-peptide precedes amyloid plaque formation in Down's syndrome. Nat. Med. 1996;2:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesné S., Koh M.T., Ashe K.H. A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh D.M., Townsend M., Selkoe D.J. Certain inhibitors of synthetic amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) fibrillogenesis block oligomerization of natural Aβ and thereby rescue long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2455–2462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4391-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao M.Q., Tzeng Y.J., Chen Y.C. The correlation between neurotoxicity, aggregative ability and secondary structure studied by sequence truncated Aβ peptides. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1161–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zagorski M.G., Shao H., Papolla M. Amyloid AB (1–40) and AB(1–42) adopt remarkably stable, monomeric, and extended structures in water solution at neutral pH. Neurobiol. Aging. 2000;21:S10–S11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrow C.J., Yasuda A., Zagorski M.G. Solution conformations and aggregational properties of synthetic amyloid β-peptides of Alzheimer's disease. Analysis of circular dichroism spectra. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;225:1075–1093. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90106-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coles M., Bicknell W., Craik D.J. Solution structure of amyloid β-peptide(1-40) in a water-micelle environment. Is the membrane-spanning domain where we think it is? Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064–11077. doi: 10.1021/bi972979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkitadze M.D., Condron M.M., Teplow D.B. Identification and characterization of key kinetic intermediates in amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:1103–1119. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarrett J.T., Berger E.P., Lansbury P.T. The carboxy terminus of the β-amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimers disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarrett J.T., Berger E.P., Lansbury P.T., Jr. The C-terminus of the β protein is critical in amyloidogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993;695:144–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baumketner A., Shea J.E. The structure of the Alzheimer amyloid β 10-35 peptide probed through replica-exchange molecular dynamics simulations in explicit solvent. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;366:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarus B., Straub J.E., Thirumalai D. Dynamics of Asp23-Lys28 salt-bridge formation in Aβ10-35 monomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16159–16168. doi: 10.1021/ja064872y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamodrakas S.J., Liappa C., Iconomidou V.A. Consensus prediction of amyloidogenic determinants in amyloid fibril-forming proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2007;41:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porat Y., Abramowitz A., Gazit E. Inhibition of amyloid fibril formation by polyphenols: structural similarity and aromatic interactions as a common inhibition mechanism. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2006;67:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuno H., Mori K., Suzuki H. Development of aggregation inhibitors for amyloid-β peptides and their evaluation by quartz-crystal microbalance. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2007;69:356–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soldi G., Plakoutsi G., Chiti F. Stabilization of a native protein mediated by ligand binding inhibits amyloid formation independently of the aggregation pathway. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6057–6064. doi: 10.1021/jm0606488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee K.H., Shin B.H., Yu J. A hybrid molecule that prohibits amyloid fibrils and alleviates neuronal toxicity induced by β-amyloid (1-42) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;328:816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nerelius C., Sandegren A., Johansson J. α-Helix targeting reduces amyloid-β peptide toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:9191–9196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810364106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reference deleted in proof.

- 33.Hong H.S., Maezawa I., Jin L.W. Candidate anti-Aβ fluorene compounds selected from analogs of amyloid imaging agents. Neurobiol. Aging. 2008;31:1690–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomaselli S., Esposito V., Picone D. The α-to-β conformational transition of Alzheimer's Aβ-(1-42) peptide in aqueous media is reversible: a step by step conformational analysis suggests the location of β conformation seeding. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:257–267. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert M.P., Barlow A.K., Klein W.L. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mastrangelo I.A., Ahmed M., Smith S.O. High-resolution atomic force microscopy of soluble Aβ42 oligomers. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Case D.A., Cheatham T.E., 3rd, Woods R.J. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duan Y., Wu C., Kollman P. A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J.M., Wolf R.M., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general Amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dennington II, R., T. Keith, …, R. Gilliland. 2003. GaussView, Version 3.09. Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission, KS.

- 41.Essmann U., Perera L., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Case D.A., Darden T.A., Kollman P.A. University of California; San Francisco: 2004. AMBER 8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J.C. Numerical-integration of Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints—molecular-dynamics of N-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen H.C. Molecular-dynamics simulations at constant pressure and/or temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:2384–2393. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiu S.W., Clark M., Jakobsson E. Collective motion artifacts arising in long-duration molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harvey S.C., Tan R.K.Z., Cheatham T.E. The flying ice cube: velocity rescaling in molecular dynamics leads to violation of energy equipartition. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:726–740. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kollman P.A., Massova I., Cheatham T.E., 3rd Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.