Abstract

STAT5a and -5b (signal transducers and activators of transcription 5a and 5b) proteins play an essential role in hematopoietic cell proliferation and survival and are frequently constitutively active in hematologic neoplasms and solid tumors. Because STAT5a and STAT5b differ mainly in the carboxyl-terminal transactivation domain, we sought to identify new proteins that bind specifically to this domain by using a bacterial two-hybrid screening. We isolated hTid1, a human DnaJ protein that acts as a tumor suppressor in various solid tumors. hTid1 interacts specifically with STAT5b but not with STAT5a in hematopoietic cell lines. This interaction involves the cysteine-rich region of the hTid1 DnaJ domain. We also demonstrated that hTid1 negatively regulates the expression and transcriptional activity of STAT5b and suppresses the growth of hematopoietic cells transformed by an oncogenic form of STAT5b. Our findings define hTid1 as a novel partner and negative regulator of STAT5b.

Keywords: Leukemia, Protein-Protein Interactions, Signal Transduction, STAT Transcription Factor, Tumor Suppressor

Introduction

STAT transcription factors play a central role in cytokine-dependent survival, proliferation, and differentiation of a large spectrum of cells. Following cytokine addition, STAT proteins become tyrosine-phosphorylated and subsequently dimerize, forming homo- or heterodimers, and translocate into the nucleus, where they bind to specific elements in the promoter of target genes and activate transcription (1). The STAT protein family comprises seven members, including the two closely related STAT5a and STAT5b molecules (2, 3). Mice in which stat5a and stat5b genes were deleted revealed redundant and specific functions of both proteins. stat5a−/− mice have a profound defect in mammary gland development and in prolactin response, whereas stat5b−/− mice display a defect in growth hormone response (4, 5). Simultaneous inactivation of stat5a/b genes demonstrated the requirement of both proteins in myeloid and lymphoid cell proliferation (6, 7). Indeed, erythroblasts, myeloid cells, mast cells, peripheral T cells, NK cells, and B cells display impaired proliferation and/or survival in mice lacking expression of STAT5 proteins (8–11). STAT5 promotes cell survival and/or proliferation by regulating the expression of genes involved in the control of cell cycle and survival like bcl-xL, cyclins D1 and D2, p21waf1, and the proto-oncogene pim-1 (12–14). Besides the physiological role of STAT5 in hematopoietic cell development, there is increasing evidence suggesting that inappropriate activation of STAT5 may contribute to the development of leukemias and solid cancers (15, 16). STAT5 is frequently hyperactivated in cancer and leukemias, most probably by alterations of tyrosine kinase activities. Importantly, STAT5 is a common and crucial target for different oncoproteins with tyrosine kinase activity, like Tel-Jak2, Bcr-Abl, the mutated forms of Flt3 and c-Kit, and the Jak2V617F mutant (17–21). Furthermore, it has been shown that STAT5 plays a critical role in Bcr-Abl- and Tel-Jak2-induced myeloproliferative disease (22, 23). The most direct evidence that constitutive activation of STAT5 is an important causative event in cell transformation came from the analysis of the STAT5 mutants, STAT5a1*6 and STAT5b1*6, and cS5F. These proteins with mutations at residues His299 → Arg and Ser711/716 → Phe (STAT5a1*6 or STAT5b1*6) or with the single mutation Ser711 → Phe (cS5F) possess constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation and are capable of inducing leukemias in mice (23, 24). In addition, STAT5b plays an important role in the proliferation and/or survival of tumor cells from head and neck cancer, glioblastomas, and prostate cancer (16, 25–27). STAT5b acts downstream of epidermal growth factor receptor, which is frequently overexpressed or hyperactivated in these tumors (28). Furthermore, STAT5b is specifically activated in T-cell lymphomas transformed by the oncogenic fusion NPM1-ALK and contributes to the NPM1-ALK oncogenesis by promoting cell growth and survival, whereas STAT5a acts as a tumor suppressor in these malignant cells (29). This suggests that STAT5a and STAT5b may have some non overlapping and opposite functions in the transformation of similar target cells.

Like other STAT family members, STAT5a and STAT5b proteins contain in their carboxyl-terminal part a transactivation domain that is required for transcriptional activation (30). In some early hematopoietic progenitors and in peripheral T cells, cleavage of full-length STAT5 proteins by proteases generates carboxyl-terminally truncated STAT5 proteins called STAT5γ that lack the transactivation domain and function as dominant negative proteins (3). Mutagenesis analyses have shown that a small amphipathic α-helical region within this domain is required not only for transcriptional activation of STAT5 proteins but also for the rapid proteasome-dependent turnover of the molecules (31). This region is also involved in the recruitment of the cofactors CBP/P300 and NCoA1/SRC-1 (32, 33). Thus, transcriptional activation and down-regulation of STAT5 proteins are mediated via a similar region located in the transactivation domain. STAT5a and STAT5b share 96% homology at the amino acid level and differ mainly in the carboxyl-terminal region. Importantly, a serine residue at position 779 that is phosphorylated in STAT5a is absent at a similar position in STAT5b (34). There is evidence that STAT5b is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues in the carboxyl terminus distinct from the residue Tyr699, which is necessary for STAT5b dimerization and activation (35). Such phosphorylations may eventually affect STAT5b intracellular trafficking or interaction with cellular proteins (36). The carboxyl-terminal regions of STAT5a and STAT5b may therefore confer distinct functions to these two molecules that might be related in part to interactions with distinct molecular partners. In this work, we aimed to identify new STAT5 transactivation domain-interacting proteins that could differentially regulate STAT5a or STAT5b activity. For this purpose, we used a bacterial two-hybrid screening approach. We have identified hTid1, a human DnaJ protein, homolog of the Drosophila tumor suppressor Tid56, as a novel and specific negative regulator of STAT5b activity and expression in hematopoietic cell lines.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Two-hybrid Screening

Murine sequences encoding the transactivation domain of STAT5a and STAT5b (amino acids 724–794 and 728–786, respectively) were amplified by PCR from pXM-STAT5a and pXM-STAT5b plasmids and subcloned into the NotI/XhoI sites of the BacterioMatchTM (Stratagene) two-hybrid bait vector pBT, creating pBT-STAT5a and pBT-STAT5b. The human Jurkat T cell cDNA library cloned into the pTRG vector was purchased from Stratagene.

The screening procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Stratagene). Briefly, the bacterial reporter strain containing the HIS3-aadA cassette was cotransformed with pBT-STAT5a or pBT-STAT5b constructs and the pTRG plasmids that were amplified and purified from the cDNA library. Transformed bacterias were then plated on selective medium lacking histidine and containing 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (Sigma), a competitive inhibitor of the His3 enzyme. The false positives were eliminated by expressing the aadA gene, which confers streptomycin resistance, as a secondary reporter. pBT-LGF2 and pTRG-Gal11P vectors were used as positive controls. DNA plasmids from positive clones obtained after two rounds of screening were isolated and sequenced.

Cell Cultures and Reagents

COS cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biological Industries), 2 mm l-glutamine, 10 units/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Parental Ba/F3 cells and the Ba/F3 cell line expressing STAT5b1*6 or STAT5a1*6 were maintained in RPMI medium as described previously (37). Human Jurkat T cells and 697 pre-B cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biological Industries), 2 mm l-glutamine, 10 units/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Recombinant murine IL-3, murine IFNγ, and human IL-7 were purchased from Valbiotech, Sigma, and Preprotech, respectively.

Plasmids and DNA Transfections

Tid1SWT, Tid1SΔN150, Tid1SΔC233, Tid1SΔC153, Tid1SΔCys, Tid1LWT, Tid1LΔCys, and Tid1Cys(220–303) DNAs were amplified by PCR from the pCMV-hTid1S or pCMV-hTid1L plasmids and then subcloned at the NotI and XhoI sites of the pIRES-hrGFP vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) containing a FLAG tag sequence. To generate knockdown vectors, hairpin oligonucleotides capable of producing siRNAs to target hTid1L/S (38) were introduced into the psiRNA-h7SKGFPzeo vector (Invivogen). In transient transfection assays, the psiRNATid1-h7SKGP or control psiRNA-luc-h7SKGFP constructs (25 μg) were electroporated in Ba/F3 cells (250 V, 960 microfarads). Electroporated cells were expanded for 24 h in medium, and the GFP+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry (Elite, BD Biosciences). Proliferation and viability were then examined by counting viable cells using the trypan blue dye exclusion method.

The −344 to −1 β-casein gene promoter-luciferase construct, the LHRR plasmid containing six copies of the STAT5-binding site linked to the minimal thymidine kinase-luciferase reporter gene, the expression vectors for murine STAT5 (pXM-STAT5a and pXM-STAT5b), and the long form of the murine prolactin receptor have been described previously (30). For the co-immunoprecipitation studies, COS cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method with 5 μg of STAT5 expression vector (pXM-STAT5 or pIRES-hrGFP-STAT5) and 5 μg of hTid1L or hTid1S expression vector (pCMV-hTid1L/S or pIRES-hrGFP-hTid1L/S). Transfected cells were extensively washed in PBS and lysed in Nonidet P-40 buffer as described previously (30). For the luciferase assays, COS cells were transfected with 25 ng of STAT5 and hTid1 expression vectors, 20 ng of the luciferase constructs, and 30 ng of the prolactin receptor plasmid. 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated overnight with or without 1 μg/ml prolactin and then lysed in 20 μl of luciferase lysis buffer (25 mm Tris-orthophosphate, 8 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 15% glycerol). The luciferase activities were measured in a luminometer (Berthold, PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot

Whole cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto cellulose membrane (Hybond-C supermembrane; Amersham Biosciences). Blots were incubated with antibodies raised against STAT5b and STAT5a (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA); FLAG (Stratagene); and actin (C-11), hTid1S/L, hTid1S, hTid1L, and Bcl-XL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as described previously (39).

RESULTS

Identification of hTid1 as a STAT5b-interacting Protein

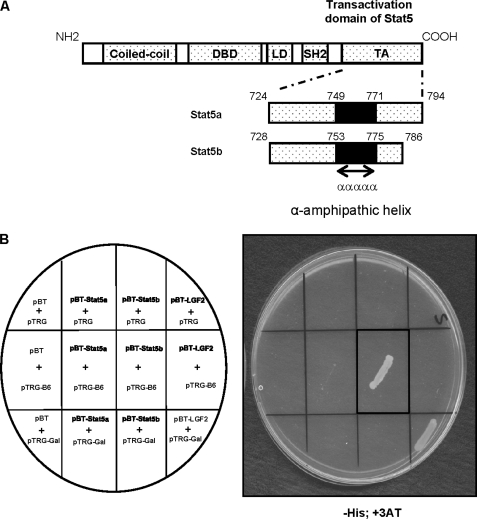

To analyze the regulation and function of STAT5a and STAT5b, we sought to identify proteins that specifically interact with the carboxyl-terminal transactivation domain of these two molecules using the BacterioMatchTM two-hybrid system (Fig. 1A). Screening of a human Jurkat T cell cDNA library with the transactivation domain of STAT5b (amino acids 728–786) as bait, allowed us to isolate four positive clones that were identified to encode the DnaJ domain of hTid1, the human homolog of the Drosophila tumor suppressor Tid56. The specificity of this interaction was further confirmed by co-transformation of bacterias with the pBT-STAT5a or pBT-STAT5b constructs and the pTRG-B6 plasmid DNA encoding the DnaJ domain of hTid1 (Fig. 1B). Only bacterias containing both pBT-STAT5b and pTRG-B6 or the positive control plasmids (pBT-LGF2 and pTRG-Gal) were able to grow on selective medium (−His, +3-amino-1,2,4-triazole).

FIGURE 1.

The transactivation domain of STAT5b interacts with hTid1 in bacterias. A, schematic representation of the transactivation domain (TA) of STAT5a and STAT5b used in the bacterial two-hybrid screening. DBD, DNA-binding domain; SH2, Src homology 2 domain. B, bacterias were transformed with the plasmid pTRG-B6 (containing the DnaJ domain of hTid-1) and pBT-STAT5a, pBT-STAT5b, or the empty vector pBT as indicated. Bacterias were also transformed with the constructs pBT-LGF2 and pTRG-Gal11P as positive controls. The transformed cells were selected on plates containing the inhibitor 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (+3AT) and lacking the amino acid histidine. The presence of transformed bacterias on the plate containing selective medium is shown. LD, Linker domain.

Physiological Association of STAT5b and hTid1 in Various Cell Types

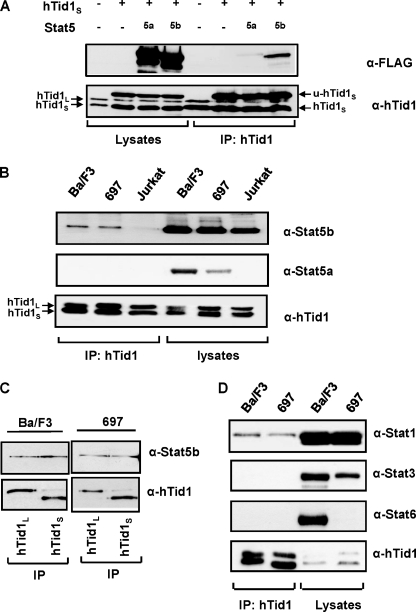

The htid1 gene encodes two spliced variants of hTid1, a long form hTid1L and a short form hTid1S (40). To verify the interaction of STAT5b with hTid1L or hTid1S, we first transfected COS cells with expression vectors encoding hTid1S, the FLAG-tagged form of STAT5a or STAT5b, or the control empty plasmids. Expression of STAT5a, STAT5b, and hTid1 was first analyzed by Western blot with an anti-FLAG antibody and an anti-hTid1 antibody that recognizes both the long and short forms of hTid1. Expression of endogenous hTid1L and hTid1S was observed in mock-transfected COS cells (Fig. 2A, left). The level of hTid1S protein was further increased after transfection with the Tid1S construct. An additional protein with an apparent molecular mass of 45 kDa corresponding to the non-processed form of hTid1S was also detected (u-hTid1S). Cell lysates were next immunoprecipitated with an anti-hTid1 antibody, and the presence of STAT5a or STAT5b in the immunoprecipitates was determined by Western blot with the anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 2A). Expression of STAT5b and, very weakly, of STAT5a was detected in hTid1S immunoprecipitates. Similar results were obtained when COS cells were transfected with an hTid1L expression vector (data not shown). We then analyzed whether endogenous STAT5 transcription factors interact with hTid1 in three human and murine lymphoid cell lines that express STAT5a and STAT5b: the human Jurkat T, the murine Ba/F3 pro-B, and the 697 human pre-B cell lines. In these cells, STAT5a and STAT5b have been previously shown to be phosphorylated and to regulate cell growth and survival upon stimulation with IL-2, IL-3, and IL-7 (12, 41). We found that STAT5b but not STAT5a interacted with hTid1 in all three cell lines, albeit weakly in the Jurkat T cell line (Fig. 2B). We next determined whether each of the hTid1 isoforms, hTid1L and hTid1S, associates with STAT5b in Ba/F3 and 697 cells. For this purpose, hTid1L or hTid1S were first immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies from both types of cells, Ba/F3 and 697 cell extracts and the presence of STAT5b was detected by Western blotting (Fig. 2C). In keeping with the results obtained in transfected COS cells, hTid1L and hTid1S were found to interact with STAT5b in these cells. To analyze the specificity of the STAT5b-hTid1 interaction, we determined the presence of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT6 in the anti-hTid1 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 2D). Only STAT1 and not STAT3 or STAT6 was found to interact with hTid1 in Ba/F3 and 697 cells.

FIGURE 2.

Association of STAT5b and hTid1 in transfected cells and hematopoietic cell lines. A, transfected COS cell extracts expressing FLAG-tagged STAT5a or FLAG-tagged STAT5b and the short form of hTid1 (hTid1S) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-hTid1 antibody. The association of STAT5a and STAT5b with hTid1S was then analyzed by Western blot using an anti-FLAG antibody. Endogenous hTid1L and hTid1S proteins are shown on the left, whereas the two forms of hTid1S (the unprocessed and mature forms, u-hTid1S and hTid1S) are shown on the right. B, STAT5b interacts with hTid1 in various murine and human lymphoid cell lines. Ba/F3, Jurkat, and 697 cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with an anti-hTid1 antibody, and the presence of STAT5 in the immunoprecipitates was detected by Western blot using anti-STAT5a and anti-STAT5b antibodies. C, STAT5b interacts with the long form (hTid1L) or the short form (hTid1S) of hTid1. Ba/F3 and 697 cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with antibodies that specifically recognize hTid1L or hTid1S. The presence of STAT5b in the immunoprecipitates was then determined by Western blot using STAT5b antibodies. D, interaction of STAT1 but not STAT3 or STAT6 with hTid1. Ba/F3 and 697 cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with an anti-hTid1 antibody. The presence of STAT1, STAT3, or STAT6 in the immunoprecipitates was then determined by Western blot using the indicated antibodies.

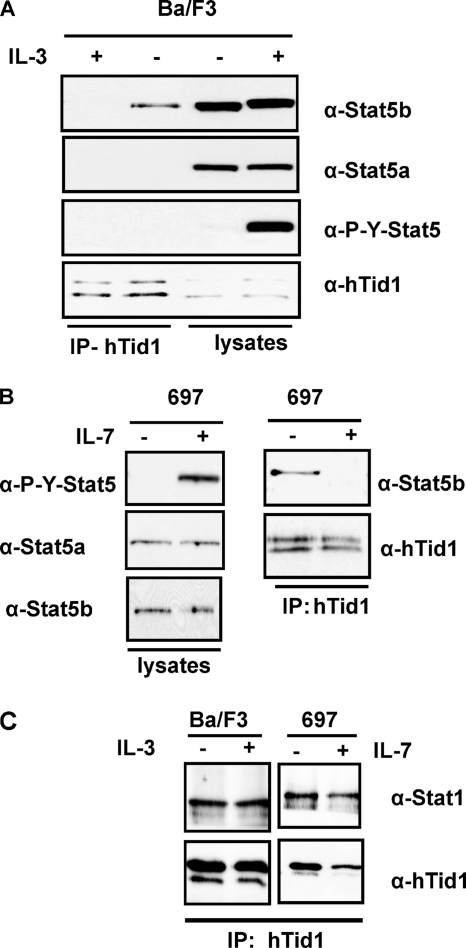

We then determined whether or not cytokine-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5b could affect the association between STAT5b and hTid1. hTid1 was immunoprecipitated from Ba/F3 cells unstimulated or stimulated with IL-3 for 30 min, and the co-immunoprecipitation of STAT5b was next determined by Western blotting. Results clearly showed that the interaction between hTid1 and STAT5b was disrupted in cytokine-stimulated cells. (Fig. 3A). A similar experiment was conducted in the 697 pre-B cells, which enabled us to demonstrate that IL-7-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5b was also associated with the loss of STAT5b and hTid1 interaction (Fig. 3B). In sharp contrast, treatment of Ba/F3 and 697 cells with IL-3 and IL-7, respectively, did not change the association between STAT1 and hTid1, although both cytokines were able to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of this transcription factor (Fig. 3C) (data not shown). Furthermore, we found evidence that the cytokine-induced phosphorylation of Tyr699 on STAT5b is involved in the dissociation of this transcription factor from hTid1 (supplemental Fig. 1). Collectively, our findings showed that STAT5b specifically interacts with hTid1 in lymphoid cells and that Tyr699 phosphorylation on STAT5b negatively regulates this association.

FIGURE 3.

Dissociation of the STAT5b-hTid1 complex upon ligand-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5. A, extracts from Ba/F3 cells treated or not with IL-3 for 30 min were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-hTid1 antibody, and the presence of STAT5 was determined by Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. B, a similar experiment was conducted with the human 697 pre-B cells treated with IL-7. C, the association of STAT1 with hTid1 was also analyzed by Western blot after immunoprecipitation of hTid1 from unstimulated or stimulated Ba/F3 and 697 cell extracts.

hTid1 Inhibits the Transcriptional Activity of STAT5b

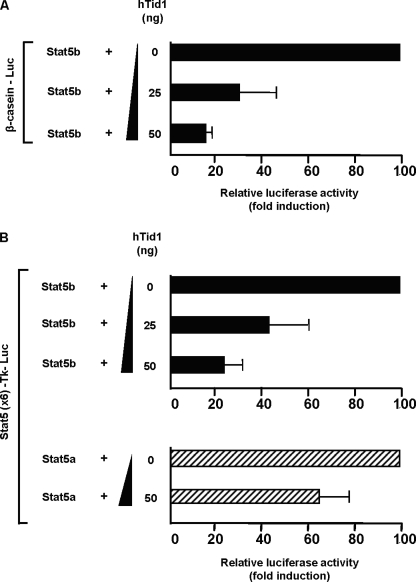

Because hTid1 interacts with the carboxyl-terminal transactivation domain of STAT5b, we tested whether hTid1 could interfere with the transcriptional activity of STAT5b. To evaluate this effect, increasing amounts of hTid1S expression vector were co-transfected in COS cells with expression vectors for STAT5b together with the prolactin receptor and the STAT5-regulated β-casein promoter-luciferase construct. After prolactin stimulation, luciferase activity was determined in transfected cell extracts (Fig. 4A). Results clearly showed that hTid1 inhibits luciferase activity in a dose-dependent fashion.

FIGURE 4.

hTid1 suppresses the transcriptional activity of STAT5b. A, COS cells were transfected with the STAT5-specific β-casein promoter luciferase construct (20 ng), the STAT5b (25 ng), and the prolactin receptor (30 ng) expression vectors and increasing amounts of hTid1S plasmid DNA as indicated. Transfected COS cells were stimulated with prolactin (5 ng/ml) and lysed, and the luciferase activities were determined. Results are the mean of four independent experiments. B, a similar experiment was conducted with a thymidine kinase-luciferase reporter construct containing six copies of the STAT5 response element of the β-casein promoter (Stat5 × 6-Tk-luciferase). The specific inhibition of STAT5b transcriptional activity induced by hTid1 was also evaluated in cells transfected with a STAT5a expression vector. Error bars, S.D.

A similar experiment was conducted with a multimerized STAT5 binding site coupled to a thymidine kinase promoter-luciferase construct (Fig. 4B). We showed that increasing amounts of hTid1 plasmids strongly inhibited STAT5b-induced and weakly affected STAT5a-induced luciferase activity. These data indicated that hTid1 preferentially and negatively regulates STAT5b transcriptional activity in transfected COS cells.

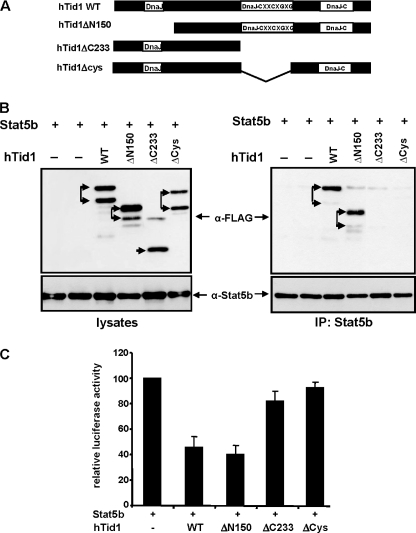

hTid1 Interacts with STAT5b through the Cysteine-rich Region of the DnaJ Domain

To further delineate the regions of hTid1 interacting with STAT5b, we generated different FLAG-tagged mutants of hTid1L that were deleted in the amino-terminal DnaJ domain, the central DnaJ cysteine-rich region, and/or the carboxyl-terminal DnaJ domain (Fig. 5A). These different mutants and the wild-type form hTid1L were introduced into the bicistronic expression vector carrying the GFP protein (pIREShrGFP) and then co-transfected with a STAT5b expression vector in COS cells. Expression of these mutants was first analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-FLAG antibody. All mutants were expressed with an expected molecular weight in transfected COS cells (Fig. 5B, left). We then analyzed their association with STAT5b. For this, STAT5b was immunoprecipitated from the different cell lysates, and the co-immunoprecipitation of the hTid1 mutants was determined by Western blot with an anti-FLAG antibody. Results showed that the mutant carrying the deletion ΔN150 was able to interact with STAT5b but not the mutants lacking the central DnaJ cysteine-rich domain, indicating that this region plays an important role in the association between hTid1 and STAT5b (Fig. 5B, right). We then determined whether these mutants could affect transcriptional activity of STAT5b. STAT5b and the hTid1 constructs were co-transfected in COS cells together with the STAT5 reporter construct and the prolactin receptor. After prolactin stimulation, luciferase activity was measured in transfected cell extracts (Fig. 5C). Expression of wild-type hTid1S and hTid1SΔN150 inhibited luciferase activity, whereas expression of mutant hTidSΔCys or hTid1SΔC233 did not affect or weakly affected luciferase activity. Altogether, these data indicate that hTid1 functionally interacts with STAT5b via the central cysteine-rich region of hTid1.

FIGURE 5.

hTid1 interacts with and inhibits STAT5b transcriptional activity via the central DnaJ cysteine-rich region. A, schematic representation of the hTid1 mutants. The position of the different DnaJ domains is shown. B, FLAG-tagged WT hTid1 and deletion mutants of hTid1 were transfected with a STAT5b expression vector in COS cells. Expression of the different hTid1 constructs and STAT5b was first verified by Western blot with an anti-FLAG antibody or an anti-STAT5b antibody (left). STAT5b was then immunoprecipitated (IP), and the presence of the different hTid1 variants in the immunoprecipitates was detected by Western blot with an anti-FLAG antibody. Membrane was reprobed with an anti-STAT5b antibody. The two arrows indicate the mature and non processed forms that were detected following transfection with the different hTid1 constructs. C, the inhibitory effect of the hTid1 mutants on the transcriptional activity of STAT5b was next evaluated in transfected COS cells by using the STAT5 reporter assay described in the legend to Fig. 3B. Results are the mean of four independent experiments. Error bars, S.D.

hTid1 Inhibits Expression of STAT5b in Ba/F3 Cells

It has been previously shown that hTid1 as a co-chaperone molecule regulates the stability and activity of different viral and cellular proteins (42–44). We therefore analyzed by Western blot whether hTid1 could affect expression of STAT5b in Ba/F3 cells (Fig. 6A). We found that expression of STAT5b was down-regulated in Ba/F3 cells after transient expression of hTid1L or hTid1S. In sharp contrast, expression of STAT5a was not affected. Conversely, we also analyzed the effect of hTid1 knockdown on STAT5b expression. Ba/F3 cells were transfected with a hTid1-shRNA or a control luciferase-shRNA expression vector carrying a GFP reporter. GFP+ cells were sorted after transfection, and expression of STAT5b was then evaluated by Western blot analysis. Abrogation of hTid1 expression by means of specific shRNA resulted in the up-regulation of STAT5b expression in Ba/F3 cells. We then analyzed the contribution of the DnaJ cysteine-rich region of hTid1 to the regulation of STAT5b expression in Ba/F3 cells. To do this, we compared the effects of the hTid1SΔCys mutant and the wild type form of hTid1S on STAT5b expression. Results showed that the mutant hTid1SΔCys fails to inhibit expression of STAT5b, providing evidence that the DnaJ cysteine-rich region is involved in the STAT5b down-regulation induced by hTid1S or hTid1L (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these data showed that hTid1 regulates STAT5b expression in hematopoietic cells via its DnaJ cysteine-rich region.

FIGURE 6.

hTid1 inhibits STAT5b but not STAT5a expression in Ba/F3 cells. A, Ba/F3 cells were electroporated with the empty vector or the FLAG-tagged hTid1L and hTid1S constructs as indicated. The following day, GFP+ cells were sorted, and the levels of STAT5a and STAT5b were next determined by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. Membranes were reprobed with an anti-actin antibody. Expression of hTid1L and hTid1S was also verified by Western blot with an anti-FLAG antibody (the two bands represent the mature and unprocessed forms of the FLAG-tagged hTid1L or hTid1S protein). B, Ba/F3 cells were electroporated with the psiRNAhTid1-h7SKGFP plasmid or the psiRNA-luc-h7SKGFP construct as control. GFP+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry, and expression levels of hTid1 and STAT5b were then analyzed by Western blot using the indicated antibodies. The membrane was reprobed with an anti-actin antibody. C, hTid1L and hTid1LΔCys constructs were transfected in Ba/F3 cells. After cell sorting, expression of STAT5b was determined by Western blot using an anti-STAT5b antibody. Levels of hTid1L and hTid1LΔCys proteins were also determined by Western blot with an anti-FLAG antibody (the two bands represent the mature and unprocessed forms of the FLAG-tagged hTid1L or hTid1LΔCys protein). Membrane was reprobed with an anti-actin antibody.

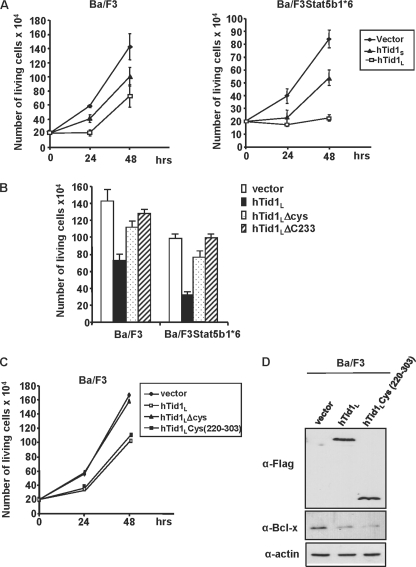

hTid1 Induces Growth Inhibition of Ba/F3 Cells

To evaluate the role of hTid1 on hematopoietic cell growth, we transiently expressed the FLAG-tagged hTid1L or hTid1S or the empty vector in parental Ba/F3 cells and Ba/F3 cells transformed by a constitutively active form of STAT5b (STAT5b1*6). We used a bicistronic expression vector, allowing the co-expression of hTid1L or hTid1 and the hrGFP indicator (pIREShrGFP) to sort by flow cytometry. We then analyzed 24 h post-transfection the behavior of GFP-expressing cells only. Rates of growth of GFP-positive cells were determined in a time course experiment (Fig. 7A). Expression of hTid1L and to a lesser extent hTid1S, inhibited Ba/F3 cell growth without altering cell survival. Strikingly, this inhibitory effect was more pronounced in Ba/F3 cells transformed by the STAT5b1*6 mutant than by the STAT5a1*6 mutant (supplemental Fig. 2). We next determined whether this growth-inhibitory effect also involves the central DnaJ cysteine-rich region. Ba/F3 cells or STAT5b1*6-expressing Ba/F3 cells were electroporated with hTid1L, hTidLΔCys, or hTid1LΔC233 expression vector or empty vector as control. 24 h later, cells were sorted by flow cytometry, and growth rates were determined 48 h later. Results clearly indicated that deletion of the central DnaJ cysteine-rich region of hTid1L almost restored the normal proliferation of Ba/F3 cells and Ba/F3 cells expressing STAT5b1*6 (Fig. 7B). To further demonstrate that the central DnaJ cysteine-rich region is crucial for this growth-inhibitory effect, we expressed a hTid1 mutant containing only the DnaJ cysteine-rich region from amino acid 220 to 303 (hTid1cys(220–303)) in Ba/F3 cells (Fig. 7C). Results showed that expression of this mutant is as efficient as wild-type hTid1L to inhibit the cell growth. We next determined whether this mutant could block transcriptional activity of STAT5 by analyzing expression of Bcl-xL, a previously identified STAT5 target in Ba/F3 cells (12) (Fig. 7D). Both wild-type hTid1L and hTid1Cys(220–303) were able to inhibit expression of this antiapoptotic molecule. Collectively, these data indicate that hTid1 inhibits STAT5b-mediated proliferation and transcriptional activity in Ba/F3 cells through its DnaJ cysteine-rich region.

FIGURE 7.

The DnaJ cysteine-rich domain of hTid1 is required for inhibition of cell growth and STAT5 activity in hematopoietic cells. A, parental Ba/F3 cells and Ba/F3 cells transformed by the constitutively active STAT5b1*6 mutant (Ba/F3STAT5b1*6) were electroporated with the FLAG-tagged hTid1L and hTid1S constructs or the empty vector as indicated. GFP+ cells were sorted 24 h later, and the number of living cells was daily enumerated. Results are the mean of three independent experiments. B, cells were also transfected with hTid1 mutants lacking the DnaJ cysteine-rich region (hTid1ΔCys and hTid1Δ233). Growth rates of transfected cells were determined 48 h after cell sorting. Results are the mean of three independent experiments. C, the DnaJ cysteine-rich domain of hTid1 is sufficient to block the growth of Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 cells were transfected with the hTid1 or hTid1ΔCys constructs or a vector expressing the FLAG-tagged DnaJ cysteine-rich domain of hTid1 (hTid1Lcys(220–303)). GFP+ cells were sorted 24 h later, and living cells were counted daily. Results are the mean of three independent experiments. D, the DnaJ cysteine-rich domain of hTid1 is sufficient to inhibit Bcl-xL expression in Ba/F3 cells. Cell extracts from GFP+ Ba/F3 cells transfected with the wild-type hTid1L or the hTid1 mutant hTid1Lcys(220–303) construct were analyzed by Western blot using anti-Bcl-xL antibody. Levels of hTid1L and hTid1LΔCys proteins were also determined by Western blot with an anti-FLAG antibody. Membrane was reprobed with an anti-actin antibody.

DISCUSSION

STAT Transcription Factors Are Important Mediators of Cytokine-induced Cell Survival and Proliferation. They transmit signals emanating from activated receptors to the nucleus in a rapid and transient manner (1). STAT activities are switched off subsequently by several and distinct negative regulatory mechanisms. These include the activities of phosphatases; inhibition by SOCS proteins (suppressors of cytokine signaling); interaction of inhibitory proteins, such as PIAS (protein inhibitor of activated STATs); and targeted proteasome-dependent degradation of active STATs (45–47). For instance, it was shown that tyrosine dephosphorylation of STAT5 is induced by distinct tyrosine phosphatases like SHP-2, PTP1B, and LMW-PTP (48–50). In addition, targeted proteasome degradation of STAT5 is mediated via their ubiquitination (47). Interestingly, The carboxyl-terminal region of Sat5 containing the transactivation domain is involved in the dephosphorylation induced by the phosphatase LMW-PTP (50). Similarly, nuclear ubiquitination and degradation of STAT5a by an as yet unidentified E3-ubiquitin ligase requires the α-amphipathic helix present in the transactivation domain of STAT5 (51). To identify specific binding of proteins to the carboxyl-terminal region of STAT5a and STAT5b, we used a bacterial two-hybrid screening and identified hTid1 as an interacting partner of STAT5b but not STAT5a. hTid1 has a high homology to Tid56, the protein encoded by the Drosophila melanogaster tumor suppressor gene l(2)tid (52). Tid56 and hTid1 have 65.8 and 54.9% amino acid similarity and identity, respectively, and thus have been well conserved through evolution (53). Tid56 and hTid1 are members of the DnaJ chaperone protein family, which contains the J domain, a highly conserved domain that binds to Hsp70 molecular chaperones (54). The DnaJ-Hsp70 complexes are involved in protein folding, protein degradation, and the assembly or disassembly of multiprotein complexes. The htid1 gene encodes two spliced variants of hTid1, hTid1L and hTid1S, with opposite functions (40). We showed in this study that both forms of hTid1 were able to interact with STAT5b in different murine and human hematopoietic cell lines and in COS cells co-expressing STAT5b and hTid1. Lu et al. (55) reported that only the long form of hTid1 interacts with STAT1 and STAT3 in the U2OS osteosarcoma cells. Our data showed that both forms of hTid1 interact with STAT1 but not STAT3 in hematopoietic cell lines. The reason for these discrepancies is not known, but they may be due to the requirement of an unidentified additional partner that is missing in some types of cells. In sharp contrast to STAT1, association of hTid1 isoforms with STAT5b is no longer detected following cell stimulation with cytokines. Phosphorylation of STAT5b on tyrosine residue Tyr699 was further shown to be involved in the dissociation of STAT5b from hTid1 upon cytokine stimulation. Nevertheless, we observed that hTid1 inhibits the transcriptional activity of STAT5b but not STAT5a in transfected COS cells, providing evidence for a specific and functional interaction between hTid1 and STAT5b. Importantly, we found evidence that hTid1 had the ability to inhibit the expression of STAT5b. Many studies have emphasized the important role of hTid1 in the regulation of stability and/or degradation of cellular proteins. For example, it was shown that hTid1 allowed the degradation of the transcription factor HIF1α by the Von Hippel-Lindau protein (43). Similarly, hTid1 may prolong the half-life of IκB kinases or act on the degradation of the receptor Erb2 in breast carcinoma cells (42, 56). It is therefore conceivable that hTid1 can regulate the stability/degradation of STAT5b. hTid1 interacts with the chaperone molecules Hsc70 and Hsp70 (40, 55). Interestingly, it was previously shown that overexpression of Hsp70 protein in leukemic cells increases the expression of STAT5 (57). Thus, it is likely that hTid1 may act on STAT5b expression via interaction with Hsp70, a hypothesis that awaits further experiments.

Our mutagenesis experiments clearly demonstrated that the DnaJ cysteine-rich region of hTid1 is essential in the down-regulation of STAT5b expression and activity. This central cysteine-rich domain resembles a zinc finger structure and contains four repeats of the motif CXXCXGXG. Previous reports have shown that this region also interacts with the human T-cell lymphotrophic virus viral protein Tax and the transcription factor Smad7, a downstream signaling effector of BMP (bone morphogenetic protein) (58, 59). Interestingly, interaction with Smad7 was shown to alter the development of chicken embryos by inhibiting the signaling induced by BMP. Although the DnaJ cysteine-rich domain is essential for the hTid1/STAT5b interaction, we cannot rule out the contribution of the DnaJ domain amino terminus in regulating the expression of STAT5b because this domain plays a role in the targeted degradation of intracellular proteins, as has been observed for the IκB-IKK complex (42). Although the physiological function of hTid1 in hematopoietic cells remains currently poorly documented, our findings and published reports suggest that hTid1 may regulate the proliferation and/or survival of hematopoietic cells (60). Importantly, we showed that hTid1 can inhibit the growth of Ba/F3 cells transformed by an oncogenic STAT5b but not a STAT5a mutant. There is a body of evidence indicating that hTid1 plays an important role in apoptosis and/or cell proliferation in various cell types (38, 40). In addition, it was shown that hTid regulates apoptosis of glioma cells and suppresses growth of head and neck cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo (61, 62). The mechanisms involved in hTid1-mediated growth suppression remain elusive because hTid1 modulates the activity of many proteins involved in signal transduction and hence in the survival/apoptosis and/or cell proliferation. Indeed, hTid1 regulates the activity and/or stability of the tyrosine kinase JAK2, the IKK-IKβ complex, and therefore the activation of NFκB as well as the HIF1α transcription factor (42, 43, 63). In addition, hTid1 interacts with the tumor suppressor APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) and regulates the activity of p53 by affecting its subcellular localization (64, 65). Our data suggest that hTid1 inhibits the growth of hematopoietic cell lines by interfering with the STAT5-dependent expression of genes involved in cell proliferation and survival, such as bcl-xL. Interestingly, several reports have shown that STAT5b but not STAT5a plays an important role in the proliferation and/or tumor invasion of glioblastoma multiforme cells and that constitutive activation of STAT5b contributes to squamous cell tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo (25, 26). The apparent opposite effects of hTid1 in these two types of tumors suggest that hTid1 interferes with STAT5b activity in these neoplastic cells. In conclusion, our findings identified hTid1 as a new partner of STAT5b that has the ability to inhibit its transcriptional activity and its effects on hematopoietic cell growth. Whether hTid1 could suppress STAT5b-mediated cell transformation needs to be investigated. The finding that the 83 amino acids containing the DnaJ cysteine-rich region of hTid1 constitute the unique STAT5b-interacting domain opens interesting perspectives in the development of short peptides that could block the oncogenic activity of STAT5b.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Karl Munger (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for the hTid1 cDNA and shRNA expression vectors.

Footnotes

This work was supported by INSERM, Association de la Recherche contre le Cancer, Ligue contre le Cancer, Conseil Régional de Picardie.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

REFERENCES

- 1. Leonard W. J. (2001) Int. J. Hematol. 73, 271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu X., Robinson G. W., Gouilleux F., Groner B., Hennighausen L. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8831–8835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buitenhuis M., Coffer P. J., Koenderman L. (2004) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36, 2120–2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu X., Robinson G. W., Wagner K. U., Garrett L., Wynshaw-Boris A., Hennighausen L. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Udy G. B., Towers R. P., Snell R. G., Wilkins R. J., Park S. H., Ram P. A., Waxman D. J., Davey H. W. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7239–7244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teglund S., McKay C., Schuetz E., van Deursen J. M., Stravopodis D., Wang D., Brown M., Bodner S., Grosveld G., Ihle J. N. (1998) Cell 93, 841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cui Y., Riedlinger G., Miyoshi K., Tang W., Li C., Deng C. X., Robinson G. W., Hennighausen L. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 8037–8047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shelburne C. P., McCoy M. E., Piekorz R., Sexl V., Roh K. H., Jacobs-Helber S. M., Gillespie S. R., Bailey D. P., Mirmonsef P., Mann M. N., Kashyap M., Wright H. V., Chong H. J., Bouton L. A., Barnstein B., Ramirez C. D., Bunting K. D., Sawyer S., Lantz C. S., Ryan J. J. (2003) Blood 102, 1290–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Socolovsky M., Fallon A. E., Wang S., Brugnara C., Lodish H. F. (1999) Cell 98, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yao Z., Cui Y., Watford W. T., Bream J. H., Yamaoka K., Hissong B. D., Li D., Durum S. K., Jiang Q., Bhandoola A., Hennighausen L., O'Shea J. J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1000–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kieslinger M., Woldman I., Moriggl R., Hofmann J., Marine J. C., Ihle J. N., Beug H., Decker T. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 232–244 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dumon S., Santos S. C., Debierre-Grockiego F., Gouilleux-Gruart V., Cocault L., Boucheron C., Mollat P., Gisselbrecht S., Gouilleux F. (1999) Oncogene 18, 4191–4199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moriggl R., Topham D. J., Teglund S., Sexl V., McKay C., Wang D., Hoffmeyer A., van Deursen J., Sangster M. Y., Bunting K. D., Grosveld G. C., Ihle J. N. (1999) Immunity 10, 249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nosaka T., Kawashima T., Misawa K., Ikuta K., Mui A. L., Kitamura T. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4754–4765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benekli M., Baer M. R., Baumann H., Wetzler M. (2003) Blood 101, 2940–2954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tan S. H., Nevalainen M. T. (2008) Endocr. Relat. Cancer 15, 367–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lacronique V., Boureux A., Monni R., Dumon S., Mauchauffé M., Mayeux P., Gouilleux F., Berger R., Gisselbrecht S., Ghysdael J., Bernard O. A. (2000) Blood 95, 2076–2083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nieborowska-Skorska M., Wasik M. A., Slupianek A., Salomoni P., Kitamura T., Calabretta B., Skorski T. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 189, 1229–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mizuki M., Fenski R., Halfter H., Matsumura I., Schmidt R., Müller C., Grüning W., Kratz-Albers K., Serve S., Steur C., Büchner T., Kienast J., Kanakura Y., Berdel W. E., Serve H. (2000) Blood 96, 3907–3914 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harir N., Boudot C., Friedbichler K., Sonneck K., Kondo R., Martin-Lannerée S., Kenner L., Kerenyi M., Yahiaoui S., Gouilleux-Gruart V., Gondry J., Bénit L., Dusanter-Fourt I., Lassoued K., Valent P., Moriggl R., Gouilleux F. (2008) Blood 112, 2463–2473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levine R. L., Wadleigh M., Cools J., Ebert B. L., Wernig G., Huntly B. J., Boggon T. J., Wlodarska I., Clark J. J., Moore S., Adelsperger J., Koo S., Lee J. C., Gabriel S., Mercher T., D'Andrea A., Fröhling S., Döhner K., Marynen P., Vandenberghe P., Mesa R. A., Tefferi A., Griffin J. D., Eck M. J., Sellers W. R., Meyerson M., Golub T. R., Lee S. J., Gilliland D. G. (2005) Cancer Cell 7, 387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoelbl A., Kovacic B., Kerenyi M. A., Simma O., Warsch W., Cui Y., Beug H., Hennighausen L., Moriggl R., Sexl V. (2006) Blood 107, 4898–4906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwaller J., Parganas E., Wang D., Cain D., Aster J. C., Williams I. R., Lee C. K., Gerthner R., Kitamura T., Frantsve J., Anastasiadou E., Loh M. L., Levy D. E., Ihle J. N., Gilliland D. G. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 693–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moriggl R., Sexl V., Kenner L., Duntsch C., Stangl K., Gingras S., Hoffmeyer A., Bauer A., Piekorz R., Wang D., Bunting K. D., Wagner E. F., Sonneck K., Valent P., Ihle J. N., Beug H. (2005) Cancer Cell 7, 87–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xi S., Zhang Q., Gooding W. E., Smithgall T. E., Grandis J. R. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 6763–6771 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liang Q. C., Xiong H., Zhao Z. W., Jia D., Li W. X., Qin H. Z., Deng J. P., Gao L., Zhang H., Gao G. D. (2009) Cancer Lett. 273, 164–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gu L., Dagvadorj A., Lutz J., Leiby B., Bonuccelli G., Lisanti M. P., Addya S., Fortina P., Dasgupta A., Hyslop T., Bubendorf L., Nevalainen M. T. (2010) Am. J. Pathol. 176, 1959–1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kloth M. T., Laughlin K. K., Biscardi J. S., Boerner J. L., Parsons S. J., Silva C. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1671–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Q., Wang H. Y., Liu X., Wasik M. A. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 1341–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moriggl R., Gouilleux-Gruart V., Jähne R., Berchtold S., Gartmann C., Liu X., Hennighausen L., Sotiropoulos A., Groner B., Gouilleux F. (1996) Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 5691–5700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang D., Moriggl R., Stravopodis D., Carpino N., Marine J. C., Teglund S., Feng J., Ihle J. N. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 392–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Litterst C. M., Kliem S., Marilley D., Pfitzner E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45340–45351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pfitzner E., Jähne R., Wissler M., Stoecklin E., Groner B. (1998) Mol. Endocrinol. 12, 1582–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Beuvink I., Hess D., Flotow H., Hofsteenge J., Groner B., Hynes N. E. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10247–10255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kloth M. T., Catling A. D., Silva C. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8693–8701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kazansky A. V., Rosen J. M. (2001) Cell Growth Differ. 12, 1–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Santos S. C., Lacronique V., Bouchaert I., Monni R., Bernard O., Gisselbrecht S., Gouilleux F. (2001) Oncogene 20, 2080–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Edwards K. M., Münger K. (2004) Oncogene 23, 8419–8431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosa Santos S. C., Dumon S., Mayeux P., Gisselbrecht S., Gouilleux F. (2000) Oncogene 19, 1164–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Syken J., De-Medina T., Münger K. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 8499–8504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lanvin O., Gouilleux F., Mullié C., Mazière C., Fuentes V., Bissac E., Dantin F., Mazière J. C., Régnier A., Lassoued K., Gouilleux-Gruart V. (2004) Oncogene 23, 3040–3047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cheng H., Cenciarelli C., Nelkin G., Tsan R., Fan D., Cheng-Mayer C., Fidler I. J. (2005) Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 44–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bae M. K., Jeong J. W., Kim S. H., Kim S. Y., Kang H. J., Kim D. M., Bae S. K., Yun I., Trentin G. A., Rozakis-Adcock M., Kim K. W. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 2520–2525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schilling B., De-Medina T., Syken J., Vidal M., Münger K. (1998) Virology 247, 74–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hilton D. J. (1999) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 55, 1568–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kile B. T., Nicola N. A., Alexander W. S. (2001) Int. J. Hematol. 73, 292–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tanaka T., Soriano M. A., Grusby M. J. (2005) Immunity 22, 729–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yu C. L., Jin Y. J., Burakoff S. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 599–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Aoki N., Matsuda T. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39718–39726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rigacci S., Talini D., Berti A. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 312, 360–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen Y., Dai X., Haas A. L., Wen R., Wang D. (2006) Blood 108, 566–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kaymer M., Debes A., Kress H., Kurzik-Dumke U. (1997) Gene 204, 91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yin X., Rozakis-Adcock M. (2001) Gene 278, 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cyr D. M., Langer T., Douglas M. G. (1994) Trends Biochem. Sci. 19, 176–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lu B., Garrido N., Spelbrink J. N., Suzuki C. K. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13150–13158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kim S. W., Chao T. H., Xiang R., Lo J. F., Campbell M. J., Fearns C., Lee J. D. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 7732–7739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Guo F., Sigua C., Bali P., George P., Fiskus W., Scuto A., Annavarapu S., Mouttaki A., Sondarva G., Wei S., Wu J., Djeu J., Bhalla K. (2005) Blood 105, 1246–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cheng H., Cenciarelli C., Shao Z., Vidal M., Parks W. P., Pagano M., Cheng-Mayer C. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1771–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Torregroza I., Evans T. (2006) Biochem. J. 393, 311–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Syken J., Macian F., Agarwal S., Rao A., Münger K. (2003) Oncogene 22, 4636–4641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Trentin G. A., He Y., Wu D. C., Tang D., Rozakis-Adcock M. (2004) FEBS Lett. 578, 323–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen C. Y., Chiou S. H., Huang C. Y., Jan C. I., Lin S. C., Hu W. Y., Chou S. H., Liu C. J., Lo J. F. (2009) J. Pathol. 219, 347–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sarkar S., Pollack B. P., Lin K. T., Kotenko S. V., Cook J. R., Lewis A., Pestka S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 49034–49042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Qian J., Perchiniak E. M., Sun K., Groden J. (2010) Gastroenterology 138, 1418–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ahn B. Y., Trinh D. L., Zajchowski L. D., Lee B., Elwi A. N., Kim S. W. (2010) Oncogene 29, 1155–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.