Abstract

Objective

Evaluate the clinical utility of electrocochleography (ECoG) for diagnosis/treatment of Meniere’s disease among members of the American Otological Society (AOS) and American Neurotology Society (ANS).

Subjects

Clinically active members of the AOS/ANS.

Main Outcome Measure

Survey responses.

Results

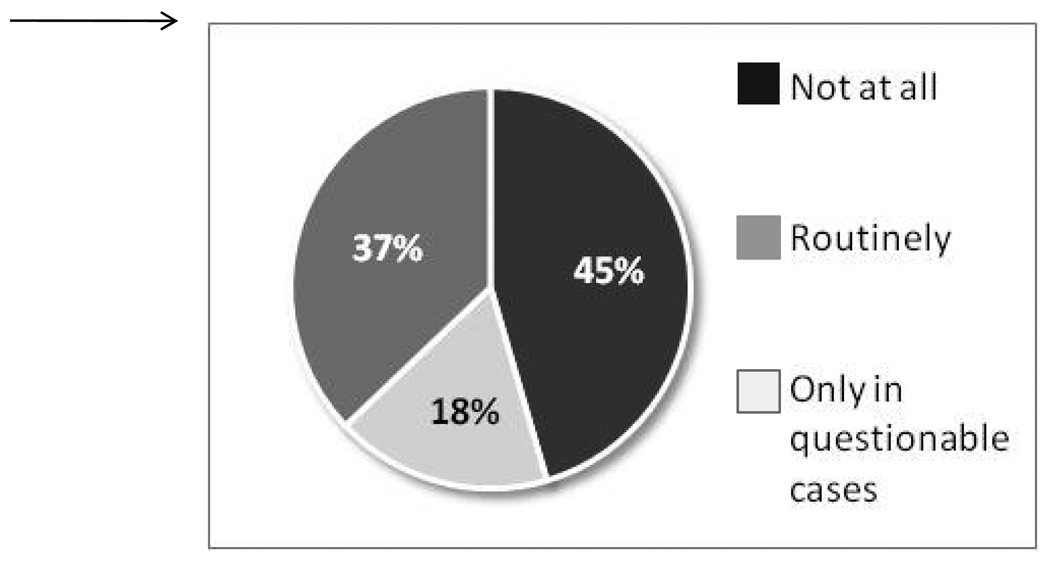

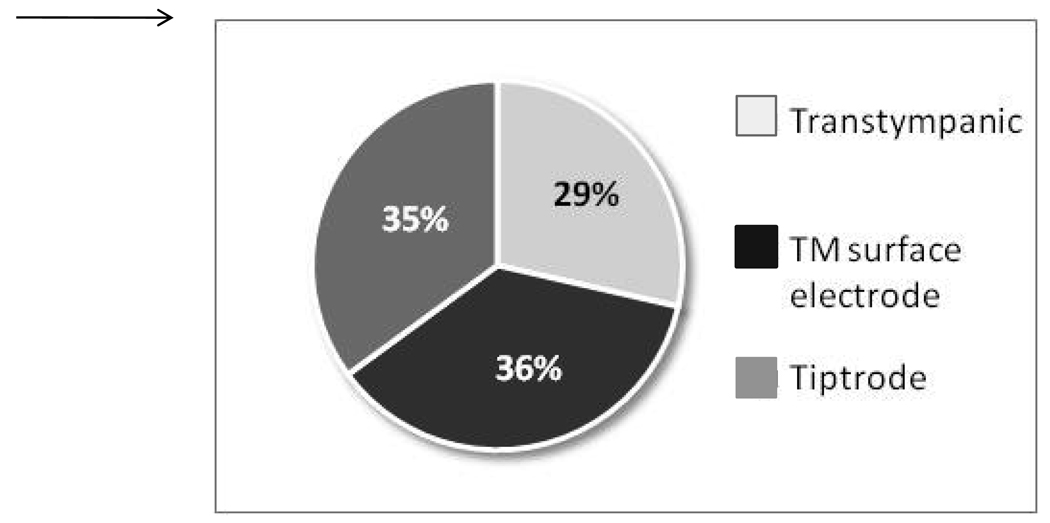

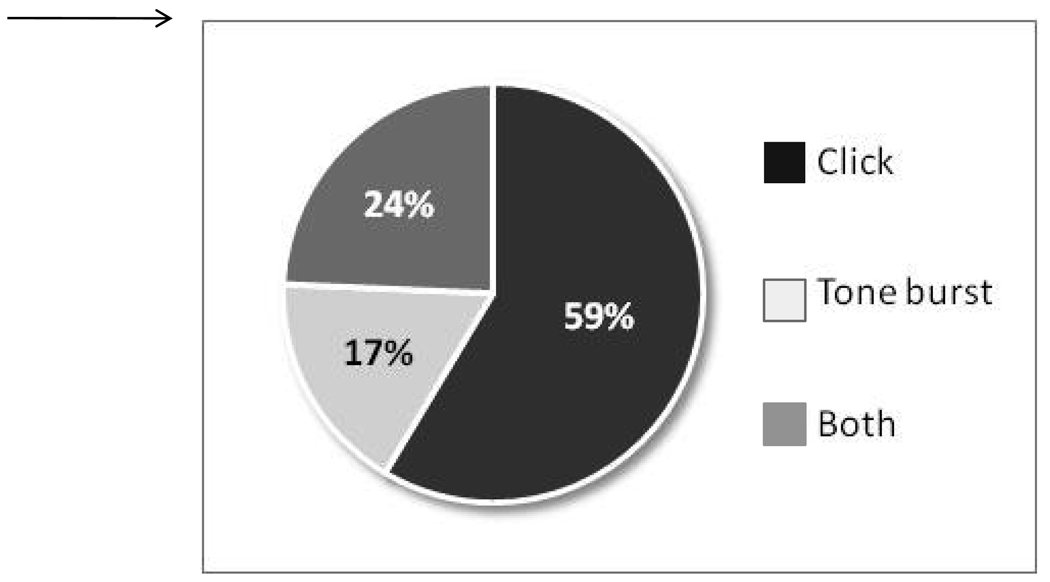

A total of 143 responses were received from 344 possible respondents (41.6%). In suspected cases of Meniere’s disease, 45.5% of respondents did not use ECoG at all, 17.5 % used ECoG routinely, and 37.1% used it only in questionable cases. ECoG users differed widely in electrode approach and stimulus modality used, with extratympanic approach and click stimuli used most frequently. A majority of respondents (73.2%) believed that ECoG is a test of indeterminate value. Only 3.6% required an abnormal ECoG to diagnose endolymphatic hydrops. An abnormal test was a requirement to proceed with ablative therapy for just 8.6% of respondents. Still, 77.9% believe that ECoG findings do fluctuate with activity of the disorder, but only 18.0% agree that when the ECoG reverts to normal, one can predict remission of symptoms. Almost half of respondents (46.7%) reported that they have now stopped ordering ECoG due to variability in results and lack of correlation with their patients’ symptoms.

Conclusion

Among AOS/ANS members, there is low clinical utility of ECoG in diagnosis/management of Meniere’s disease. For approximately half of respondents, ECoG has no role in their clinical practice. ECoG was used routinely by only one in six respondents. Those who used ECoG differed widely in electrode placement and type of stimuli paradigm used.

Introduction

Meniere’s disease is an idiopathic disorder defined by the clinical quadrad of fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, aural pressure, and episodic vertigo. In 1995, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium published an updated set of clinical guidelines to aid physicians in the diagnosis and management of patients with Meniere’s disease(1). Still, definitive diagnosis remains difficult due to the wide and varied spectrum of symptom presentation and fluctuating nature of the disease, making objective diagnostic tests especially attractive to clinicians.

Based upon histopathological studies, it is commonly suggested that endolymphatic hydrops – that is, excess volume of endolymph – is the underlying pathology of Meniere’s disease(2,3). If this is correct, electrocochleography (ECoG), widely studied as a promising objective tool in the diagnosis of endolymphatic hydrops, would seem to be an appropriate test for the diagnosis of Meniere’s disease(4). ECoG records potentials arising from the cochlea and auditory nerve during sound stimulation(5,6). Clinical evaluation of cochlear function using ECoG has focused on the amplitude ratio of the summating potential (SP) and action potential (AP)(7). An elevated SP/AP ratio is thought to reflect endolymphatic hydrops in patients with suspected Meniere’s disease.

Although there is a large body of literature on the role of ECoG in the diagnosis and management of Meniere’s disease, there is little on which authors agree. There are many studies that either support or refute its clinical utility, some that advocate for the various approaches to electrode placement, and others which debate the most effective stimulus measurement. Noting this lack of consensus on how, where, and if ECoG should be performed, we wondered how these studies related to actual clinical practice. Thus, we designed the present study to assess the role of ECoG in the diagnosis and management of Meniere’s disease among experts in the field, as determined by membership in the American Otological Society (AOS) or American Neurotology Society (ANS).

Materials and Methods

An exemption was provided for this study after review by the University of California, San Diego institutional review board. A 13-item survey was constructed after an extensive review of the literature (Appendix A). The survey was intentionally kept brief to allow for rapid completion, thereby potentially maximizing response rates. The survey was emailed or faxed to clinically active members of the AOS and ANS (n= 344) in January 2009. Responses were accepted until March 31, 2009. The mailing list for the ANS was manually cross-checked to avoid sending repeat surveys to those already included in the AOS group. Surveys were returned by email or fax. Non-respondents were emailed or faxed two additional times.

Results

344 surveys were sent out to clinically active members of the AOS and ANS. 143 were returned (41.6%) after three rounds of email or fax correspondences. In suspected cases of Meniere’s disease, we found that 45.5% of respondents did not use ECoG at all, 17.5% used the test routinely, and 37.1% used it only in questionable cases (Figure 1). The most common rationale cited for use of the test was to determine if endolymphatic hydrops is present (89.5%). Among those individuals who use ECoG, the tympanic membrane (TM) surface electrode was used most frequently by 36.4%, followed by tiptrode by 35.1%, and transtympanic needle by 28.6% (Figure 2). In regards to stimulus paradigms, 58.6% of ECoG users preferred click stimuli, while 17.1% used tone bursts, and 24.3% employed both (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Use of ECoG by AOS/ANS members in suspected cases of Meniere’s disease.

Figure 2.

Preferred electrode placement among ECoG users.

Figure 3.

Preferred stimulus paradigm among ECoG users.

In the next part of the survey, we asked participants to agree or disagree to various statements about ECoG (Table 1). The vast majority of respondents (73.2%) believed that ECoG has indeterminate value. Only 3.6% of respondents believed that a diagnosis of hydrops required an abnormal ECoG; furthermore, only 8.6% considered an abnormal ECoG a requirement before proceeding with ablative therapy. About one in four respondents (23.9%) believe that an abnormal ECoG in the opposite asymptomatic ear indicates bilateral Meniere’s disease.

Table 1.

Results of agree/disagree items.

| Agree | Disagree | |

|---|---|---|

| A diagnosis of hydrops cannot be made unless the ECoG is abnormal. | 3.6% | 96.4% |

| An abnormal ECoG in the opposite, asymptomatic ear indicates bilateral Meniere’s disease. |

23.9% | 76.1% |

| Abnormal ECoG is a requirement before ablative therapy. | 8.6% | 91.4% |

| Because abnormal ECoG results have been documented in normal research subjects, the test has indeterminate value. |

73.2% | 26.8% |

| ECoG findings fluctuate with the activity of the disorder. | 77.9% | 22.1% |

| When the ECoG reverts to normal, one can predict remission of symptoms. |

18.0% | 82.0% |

| I discount a result that is contradictory to my clinical impressions (for instance: symptomatic ear is normal and opposite asymptomatic ear is abnormal). |

82.6% | 17.4% |

| I have now stopped ordering ECoG due to the variability in results and lack of correlation with my patients’ symptoms. |

46.7% | 53.3% |

While 77.9% of survey participants believed that ECoG findings do fluctuate with activity of the disorder, 82.6% would still discount a result that was contradictory to their clinical impressions. Ultimately, 46.7% reported that they have stopped ordering the test due to variability in results and lack of correlation with the clinical picture.

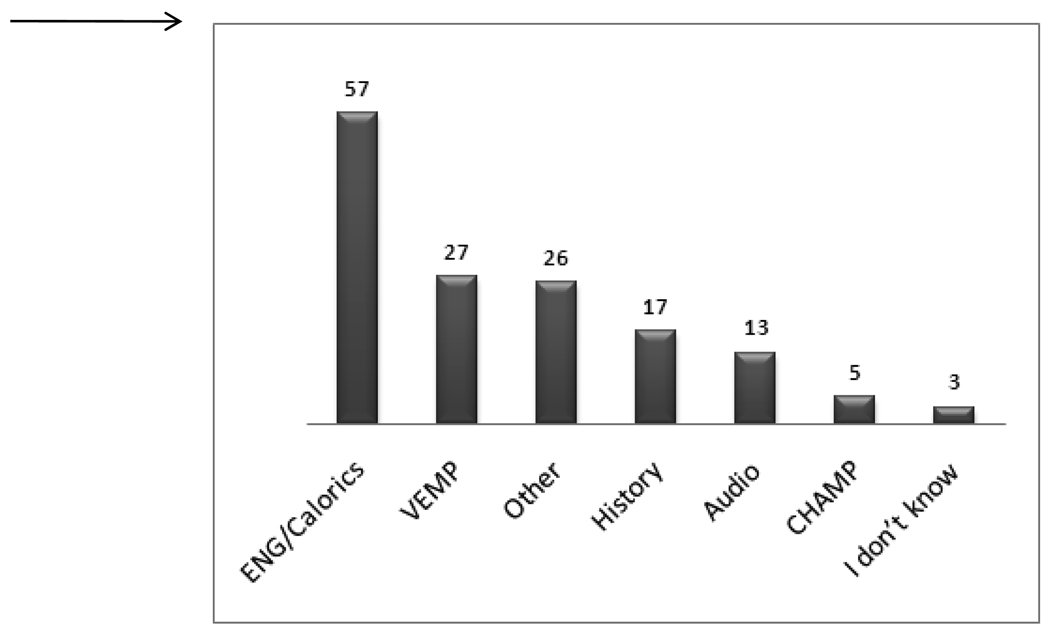

Of those respondents for whom ECoG was not the preferred test, ENG/Calorics and VEMP were most frequently listed as the diagnostic tests of choice in the management of classic unilateral Meniere’s disease (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Diagnostic tests preferred over ECoG.

Discussion

Historically, the presence of Meniere’s quadrad of symptoms (as interpreted by an experienced physician) is sufficient evidence for the diagnosis, with staging of the disorder based on frequency and severity of vertiginious episodes. The present study demonstrates that for about half of ANS/AOS members, ECoG, an objective test, has no role in how they diagnose or treat Meniere’s disease. The overwhelming majority of respondents expressed very little confidence in the test.

Among those respondents who used ECoG (slightly more than half), the primary objective in using the test was to determine the presence of endolymphatic hydrops. This rationale has been supported by many studies that have successfully demonstrated ECoG abnormalities in patients with a clinical diagnosis of endolymphatic hydrops(4,8). However, when we consider the opinions of all respondents, just 3.9% believed that a diagnosis of endolymphatic hydrops required an abnormal ECoG. This lack of confidence in ECoG as a sensitive test for endolymphatic hydrops can be reflected in various studies which have reported that 25% to 54% of patients with Meniere’s disease display normal ECoG results(5,9–11). One possible explanation for this discrepancy was put forth by Conlon et al. The authors postulated that in early Meniere’s disease, endolymphatic hydrops may be intermittent, therefore abnormal results may only be seen immediately prior to, or during, symptomatic periods(4). Recent studies refute this theory and have found a lack of correlation between the stage of Meniere’s disease and ECoG results(9,12).

The majority of survey participants (77.9%) did believe that ECoG results fluctuate with activity of the disease. Still, most did not use ECoG in the management of established Meniere’s disease. Very few individuals (8.6%) required an abnormal ECoG before proceeding with ablative therapy. An abnormal ECoG in the opposite asymptomatic ear would only concern 23.9% of respondents about bilateral Meniere’s. This lack of concern seems to pay little regard to studies by Conlon et al in which the authors found that more than 10% of contralateral asymptomatic Meniere's ears have an abnormal ECoG highly suggestive of endolymphatic hydrops (13). However, other studies analyzing how ECoG changes throughout the course of Meniere’s have challenged use of the test for disease monitoring. Ohashi et al found that abnormally elevated SP/AP ratios were maintained over several years despite medical and surgical intervention targeted at reducing endolymphatic hydrops(14).

The most interesting result of our study is the overwhelming lack of confidence in ECoG and its absence in the clinical practices of so many AOS/ANS members. This negative perception of the test most likely stems from studies such as those by Campbell et al, in which the authors found that ECoG results were not significantly different between normal subjects and Meniere’s patients for summating potential (SP) amplitude, action potential (AP) amplitude, or the SP/AP amplitude ratio(15).

Although there may not be perfect correlation between the changes in ECoG potentials and the underlying endolymphatic hydrops in patients with Meniere’s disease, ECoG still remains one of the few objective methods available to evaluate electrophysiological changes in the cochlea(12). This, perhaps, is the basis for the continued use of ECoG by more than half of the respondents to our survey. Still, a minority of respondents used ECoG regularly, with one in six (17.5%) reporting routine use of the test.

Among those who used ECoG, various methods of electrode placement were reported, with 28.6% employing the transtympanic approach and 36.4% preferring the TM surface electrode. Tiptrodes were used by 35.1%. Use of transtympanic ECoG in clinical practice is associated with several difficulties which mostly originate from the relative technical complexity of the method and the invasive nature of the transtympanic approach(12). However, transtympanic ECoG is thought to generate electrical potentials that are more robust, larger, and easier to interpret. In our study, the transtympanic approach was the least utilized, demonstrating its limitations in clinical practice. The most preferred method, extratympanic ECoG (tiptrode and TM surface electrode), was used by 71.5% of ECoG users. Though not without its own limitations, this technique is preferred due to the ease of application and less discomfort to the patient(11). Studies have shown extratympanic and transtympanic techniques to give similar recordings, except that the absolute amplitudes of transtympanic signals were larger due to the proximity to the cochlea(16,17). A recent study by Chung et al reported the sensitivity and specificity of extratympanic ECoG in the diagnosis of Meniere’s was 71% and 96%, respectively(12).

With respect to the type of stimuli used, some investigators have advocated the use of tone burst rather than click stimuli. Conlon and Gibson showed that sensitivity of transtympanic ECoG was enhanced to 85% when 1 kHz of tone burst was used to measure absolute SP(4). Though tone burst appears to improve sensitivity, in our study we found that the majority of respondents preferred click (58.6%). Only 17.2% used tone burst, and 24.3% employed both types of stimuli.

It is important to note the inherent limitations of a survey study such as this. Because the study relied on self-reporting, many factors could have influenced the response rate and value of the data. Surveys are subject to biases held by both authors and respondents, with results based on opinion and memory and not objective scientific data. However, we point out that the questions did not ask participants to provide any hard numbers, but only queried perceptions and practice methods. While acknowledging the realities of survey studies, we believe this study provides valuable insight into current practice patterns.

As voiced by many survey participants, Meniere’s disease is a clinical diagnosis for which tests such as ECoG should only be adjunct to the history and physical exam. As such, almost half of the respondents to our survey have completely excluded ECoG from their practice. However, it is paradoxical that slightly more than half of respondents continue to use ECoG even when the overwhelming majority perceives it to be a faulty and imperfect test. Perhaps this demonstrates that when it comes to Meniere’s disease, it is better to have a flawed objective test than no objective test at all.

Conclusion

Though a variety of tests exists to aid clinicians in the diagnosis and management of Meniere’s disease, the mainstay of treatment remains anchored in clinical history, symptoms, and audiogram. In the present study, we find that among AOS and ANS members, ECoG is perceived to have low clinical utility and reliability in the diagnosis and management of Meniere’s disease. However, slightly more than half of respondents continue to use the test to various degrees. Among those who used ECoG, there was little consensus on the technique and stimuli modalities employed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. George Gates for guidance and input throughout this project.

Funding: Linda Nguyen is supported by NIH grant T32 RR023254.

Appendix A

STATUS OF ELECTROCOCHLEOGRAPHY FOR MENIERE’S DISEASE

The role of electrocochleography (ECoG) in the diagnosis and monitoring of treatment for Meniere’s disease remains controversial. When the ECoG results confirm a clinical diagnosis, the physician can be reasonably confident in proceeding with invasive therapy. However, when discrepancies exist, such as people with typical symptoms but a normal ECoG and vice versa, how is the physician to interpret the conflicting results? Should one treat the symptoms or the test?

As part of a review of this subject, a survey of experts is planned by asking the members of the AOS/ANS for their opinions. To facilitate your participation, kindly underline or bold your answers and return the survey by email (L25nguyen@ucsd.edu) or fax (858-534-5270). The results will be distributed to all respondents.

For cases of suspected classic unilateral Meniere’s disease I use ECoG (select one): (a) not at all, (b) routinely, (c) only in questionable cases.

My rationale for use is (select all that apply): (a) to determine if endolymphatic hydrops is present, (b) to stage the disorder, (c) to exclude hydrops.

My standard technique is (select one): (a) transtympanic needle, (b) TM surface electrode, (c) tiptrode.

The stimulus paradigm I use most often is (select one): (a) click, (b) tone-burst, (c) both, (d) neither, (e) other _________________.

If ECoG is NOT your preferred technique used in the diagnosis/management of suspected classic unilateral Meniere’s disease, which of the following options (if any) would you rather use (select all that apply): (1) CHAMP (cochlear hydrops analysis masking procedure), (2) VEMP, (3) ENG/calorics, (4) other ________________ (5) I don’t know.

I agree/disagree with the following statements

-

6

A diagnosis of hydrops cannot be made unless the ECoG is abnormal: Agree / Disagree

-

7

An abnormal ECoG in the opposite, asymptomatic ear indicates bilateral Meniere’s disease: Agree / Disagree

-

8

Abnormal ECoG is a requirement before ablative therapy: Agree / Disagree

-

9

Because abnormal ECoG results have been documented in normal research subjects, the test has indeterminate value: Agree / Disagree

-

10

ECoG findings fluctuate with the activity of the disorder: Agree / Disagree

-

11

When the ECoG reverts to normal, one can predict remission of symptoms: Agree / Disagree

-

12

I discount a result that is contradictory to my clinical impressions (for instance: symptomatic ear is normal and opposite asymptomatic ear is abnormal): Agree / Disagree

-

13

I have now stopped ordering ECoG due to the variability in results and lack of correlation with my patients’ symptoms: Agree / Disagree

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Megerian CA, Sofferman RA, McKenna MJ, et al. Fibrous dysplasia of the temporal bone: ten new cases demonstrating the spectrum of otologic sequelae. Am J Otol. 1995;16:408–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paparella MM. Pathology of Meniere's disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1984;112:31–35. doi: 10.1177/00034894840930s406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuknecht HF. Meniere's disease, pathogenesis and pathology. Am J Otolaryngol. 1982;3:349–352. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(82)80009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conlon BJ, Gibson WP. Electrocochleography in the diagnosis of Meniere's disease. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;120:480–483. doi: 10.1080/000164800750045965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson WP. The use of electrocochleography in the diagnosis of Meniere' s disease. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1991;485:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson WP, Prasher DK. Electrocochleography and its role in the diagnosis and understanding of Meniere's disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1983;16:59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ge X, Shea JJ., Jr Transtympanic electrocochleography: a 10-year experience. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:799–805. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200209000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferraro JA, Arenberg IK, Hassanein RS. Electrocochleography and symptoms of inner ear dysfunction. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111:71–74. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1985.00800040035001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HH, Kumar A, Battista RA, et al. Electrocochleography in patients with Meniere's disease. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappas DG, Jr, Pappas DG, Sr, Carmichael L, et al. Extratympanic electrocochleography: diagnostic and predictive value. Am J Otol. 2000;21:81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(00)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sass K. Sensitivity and specificity of transtympanic electrocochleography in Meniere's disease. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118:150–156. doi: 10.1080/00016489850154838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung WH, Cho DY, Choi JY, et al. Clinical usefulness of extratympanic electrocochleography in the diagnosis of Meniere's disease. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:144–149. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conlon BJ, Gibson WP. Meniere's disease: the incidence of hydrops in the contralateral asymptomatic ear. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1800–1802. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199911000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohashi T, Ochi K, Okada T, et al. Long-term follow-up of electrocochleogram in Meniere's disease. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1991;53:131–136. doi: 10.1159/000276205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell KC, Harker LA, Abbas PJ. Interpretation of electrocochleography in Meniere's disease and normal subjects. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992;101:496–500. doi: 10.1177/000348949210100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roland PS, Yellin MW, Meyerhoff WL, et al. Simultaneous comparison between transtympanic and extratympanic electrocochleography. Am J Otol. 1995;16:444–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruth RA, Lambert PR, Ferraro JA. Electrocochleography: methods and clinical applications. Am J Otol. 1988;9 Suppl:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]