Abstract

Background

Pain and fatigue are recognized as critical symptoms that impact quality of life (QOL) in cancer, particularly in palliative care settings. Barriers to pain and fatigue relief have been classified into three categories: patient, professional, and system barriers. The overall objective of this study was to test the effects of a clinical intervention on reducing barriers to pain and fatigue management in oncology.

Methods

This longitudinal, three-group, quasi-experimental study was conducted in three phases: phase 1 (usual care), phase 2 (intervention), and phase 3 (dissemination). A sample of 280 patients with breast, lung, colon, or prostate cancers, stage III and IV disease (80%), and a pain and/or fatigue of 4 or more (moderate to severe) were recruited. The intervention group received four educational sessions on pain/fatigue assessment and management, whereas the control group received usual care. Pain and fatigue barriers and patient knowledge were measured at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months post-accrual for all phases. A 3 × 2 repeated measures statistical design was utilized to derive a priori tests of immediate effects (baseline to 1 month) and sustained effects (baseline or 1 month to 3 months) for each major outcome variable, subscale, and/or scale score.

Results

There were significant immediate and sustained effects of the intervention on pain and fatigue barriers as well as knowledge. Measurable improvements in QOL were found in physical and psychological well-being only.

Conclusion

A clinical intervention was effective in reducing patient barriers to pain and fatigue management, increasing patient knowledge regarding pain and fatigue, and is feasible and acceptable to patients.

Introduction

Major deficiencies in the treatment of cancer symptoms have been documented over the past two decades. Efforts to provide optimal symptom management in cancer are hampered by barriers related to patient, professional, and system issues. Suffering from uncontrolled pain is one of the greatest fears of cancer patients.1,2 Patients are reluctant to report their pain due to fear of side effects, fatalism about the possibility of achieving pain control, fear of distracting physicians from treating the cancer, and belief that pain is indicative of progressive disease.3–13 Physicians, nurses, and other members of the interdisciplinary team often fail to adequately assess pain or to recognize patient barriers.14–18 Professionals lack knowledge of the principles of pain relief, side effect management, or understanding of key concepts such as addiction, tolerance, dosing, and communication.19–22 System barriers include reimbursement and regulatory constraints, and lack of referrals to pain specialists and supportive care services.10,23,24

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is one of the most common symptoms experienced by patients with cancer.25,26 Patient-related barriers to fatigue include reluctance to report fatigue, and beliefs that fatigue is inevitable, unimportant, and untreatable.27–32 Professionals are unaware of the principles of fatigue assessment and management, and may be unwilling to initiate discussion about fatigue with patients.30,33–39 Documentation of fatigue assessment and management in the medical record is lacking in most clinical settings. Lack of health care reimbursement for fatigue affects the availability of medications, prescription practices, and referral patterns to supportive care services.28

After decades of efforts to advance symptom management, sources have documented that reducing these barriers requires more than publication of guidelines or staff education.40,41 Model programs have emphasized patient teaching interventions including the use of pain assessment tools, strategies to dispel misconceptions, and patient coaching regarding the reporting and documenting of their symptoms.42,43 The “Passport to Comfort” intervention was designed and implemented in response to the overwhelming evidence of the impact of these barriers on symptom management, and the intent to move beyond descriptive studies to test innovative models that would eliminate these barriers in palliative care settings.

Methods

This longitudinal, three-group, quasi-experimental study was designed in three phases. Phase 1 assessed patient pain and fatigue management in usual care to describe the current status of pain and fatigue management in the sample population and setting. In phase 2, all patients were offered the intervention. This included structured patient education and systems change efforts carried out by the research team. During phase 3, the intervention was disseminated within the institution so that it can be sustained for continued practice.

Sample

Patients with cancer recruited for the study met the following eligibility criteria for enrollment: (1) diagnosis of breast, colon, lung, or prostate cancer; (2) time since diagnosis of at least 1 month; (3) an expected prognosis of at least 6 months; and (4) subjective pain and/or fatigue rating of 4 or greater (moderate to severe pain) on a numeric scale of 0–10 (0 = none; 10 = worst imaginable). Stratification was conducted to reflect a sample of the four diagnoses that were proportional to the cancer center population. Participants were recruited from the ambulatory clinic of one National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated comprehensive cancer center in Southern California. The Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and monitored study progress.

Procedure

Potential participants were screened at the ambulatory clinics, and once eligibility was determined, study purpose and procedures were introduced. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. For phase 1 (usual care), all participants completed questionnaires at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months. For phase 2 (intervention), baseline questionnaires were completed prior to the intervention. The intervention was delivered by trained advanced practice nurses (APN) through four education sessions. At each session, information pertaining to pain assessment, pain management, fatigue assessment, and fatigue management was provided. A teaching material packet was also provided, and it included the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for patients on pain and fatigue and “tip sheets,” which were 1-page education sheets on nutrition, sleep disturbance, emotional issues, and exercise. Questionnaires were then repeated at 1 and 3 months. Beginning at 1 month, all participants were supported through phone calls made every 2 weeks. Length of intervention was tailored to the patient's needs and was approximately 60 minutes in length. For phase 3 (dissemination), participants completed questionnaires only at baseline, 1, and 3 months, and received phone calls every 2 weeks. In this phase, the APN role was less involved in direct professional and patient education. Her main role was to facilitate the intervention as it was implemented into the existing systems in order to sustain improved pain and fatigue management after the conclusion of the project.

Instruments

The Demographic and Treatment Data Tool was designed by the investigators to capture key disease and treatment variables of importance in describing the population and for analysis of influencing variables. Demographic and treatment data such as age, gender, disease type, stage of disease, treatments, and performance status using the Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS)44 were collected at baseline.

The Barriers Questionnaire (BQ II) was developed by Gunnarsdottir and colleagues45 to measure patient-reported barriers to pain management. Significant (t = −2.16, p < 0.05) construct validity and a factor analysis revealed four factors: (1) physiologic effects, (2) fatalism, (3) communication and (4) harmful effects. The BQ-II total has an internal consistency reliability coefficient α of 0.89 (n = 134), and a range of 0.75–0.85 for the subscales.

The Patient Pain Knowledge Tool was developed by the investigators based on the NCCN Pain Guidelines.46 This 15-item questionnaire was used as an assessment of patients' knowledge and beliefs. The questions were based on content from the NCCN pain guidelines and were in a true or false format. This tool was written at a low literacy level and to be less burdensome for subjects to complete. Internal consistency reliability analysis was performed, and Cronbach α was 0.67.

The Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS) is a 22-item, self-report scale that measures four dimensions of subjective fatigue (behavioral/severity [6 items], sensory [5 items], cognitive/mood [6 items], and affective meaning [5 items]) confirmed by principal axes factor analysis.47 Internal consistency (Cronbach α) reliabilities were strong (0.83–0.97) for the PFS and its subscales across various cultures, languages, and diagnostic groups and were 0.89–0.97 in this sample. Each item is measured on a 0–10 numeric rating scale, and higher scores indicate more fatigue. Mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), and severe (7–10) levels have been validated with declines in physical functioning (MOS-SF-36 Physical Functioning subscale and PFS-Total scores). Five additional items, not included in the scale's scoring, assess perceived causes, relief measures, additional fatigue descriptors, presence of other symptoms, and duration of fatigue.47

The Fatigue Barriers Scale (FBS) is an investigator-developed 13-item scale designed to elicit patient beliefs and attitudes that might serve as barriers to effective fatigue assessment and management. It was developed based on an extensive literature review and clinical experience. In this study, the reliability estimates for the subscales were: Beliefs/Attitudes (r = 0.30), Good Patient (r = 0.65), and Fatalism (r = 0.54). For the total scale (r = 0.73) the reliability coefficient indicated good reliability for a new scale.

The Patient Fatigue Knowledge Tool is an investigator-developed scale that contains 15 true and false statements about fatigue designed to assess a patient's knowledge about what fatigue is, and how it can be assessed, measured and treated. It was developed based on the NCCN fatigue guidelines, and was designed to capture key patient-related knowledge barriers.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was planned based on preliminary power analysis. There were 83 patients in usual care, 104 in intense intervention, and 93 in the dissemination phase. Eligible subjects were recruited and consented until the accrual goal of 100 patients per phase was reached. Data were audited for accuracy and scored according to the guidelines for each instrument. A missing values analysis was conducted and values were found to be missing at random (MAR), and therefore were imputed using the estimation-maximization method. A total of 280 patients were included in the final analysis. After examining initial results indicating no significant differences between intensive intervention and dissemination, the phase 2 and phase 3 groups were collapsed, and a 3 × 2 repeated measures statistical design was utilized to derive a priori tests of immediate effects (baseline to 1 month) and sustained effects (baseline or 1 month to 3 months) for each major outcome variable, subscale, and/or scale score. Patients achieving the criterion of having pain at study baseline, a single item pain score of 4 or greater on a 0–10 point scale, (n = 113) were included in all analyses of pain variables, while patients achieving the criterion of having fatigue at baseline, a single item fatigue score of 4 or greater on a 0–10 point scale, (n = 251) were included in all analyses of fatigue barriers. Patients who met the criteria for having pain and fatigue at baseline (n = 86) were included in both sets of analyses. All patients were included in the description of study demographics and the QOL item and subscale/scale scores. Association between group and categorical demographic variables was tested using the χ2 statistic or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. α for this study was set at 0.05, two-tailed, and when indicated a Bonferroni adjustment factor was used to control for inflation of experimentwise error.

Results

Study recruitment began November 17, 2005 to July 24, 2009. Final sample sizes by study phase (including participants with complete, evaluable data) were as follows: 83 for phase 1, 104 for phase 2, and 93 for phase 3. The demographics of study patients are presented in Table 1. Importantly, over one third of the patients were racial or ethnic minorities and a quarter of the patients each had colon or lung cancer. Few patients were receiving supportive services. The usual care group was significantly more likely to be experiencing a recurrence (42%) whereas the intervention group was more likely to have a recent diagnosis (44%) (p = 0.005). Usual care patients were significantly more likely to be diagnosed at stage III and intervention patients at stage IV (p = 0.006).

Table 1.

Demographics and Treatment Data (N = 280)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean = 60.4 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 109 | (38.9) |

| Female | 171 | (61.1) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 180 | (64.3) |

| African American | 27 | (9.6) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 41 | (14.7) |

| Other | 32 | (11.4) |

| Education | ||

| Graduate | 56 | (20) |

| College | 122 | (43.4) |

| High school or less | 102 | (36.6) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 174 | (62.1) |

| Other | 106 | (37.9) |

| Type of Cancer | ||

| Breast | 109 | (38.9) |

| Colon | 56 | (20) |

| Lung | 72 | (25.7) |

| Prostate | 43 | (15.4) |

| Stage | ||

| I–II | 56 | (20.3) |

| III | 82 | (29.7) |

| IV | 138 | (50) |

| Disease status | ||

| Recently diagnosed and undergoing rx | 141 | (50.9) |

| Recurrence and undergoing rx | 84 | (30.3) |

| Completed rx, NED | 20 | (7.2) |

| Other | 32 | (11.6) |

| Symptom Clusters | ||

| Pain only | 27 | (9.7) |

| Fatigue Only | 167 | (59.6) |

| Pain & Fatigue | 86 | (30.7) |

KPS range = 80–70 at baseline.

Single-item pain and fatigue scores over time are shown in Table 2. In the usual care group there was a significant immediate effect, but this improvement was not sustained. There was a significant immediate and sustained effect on pain for patients in the intervention group. The same pattern was demonstrated for fatigue.

Table 2.

Pain and Fatigue Scores X (95% CI) from Single Item Scales

| Baseline | 1 month | 3 month | Immediate effect | Sustained or delayed effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain scores for patients with pain | |||||

| Usual care | 5.5 (5.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.2, 4.8) | 5.1 (4.2, 6.1) | p = 0.007 | p = 0.013 |

| Intervention | 5.5 (5.1, 5.9) | 3.9 (3.3, 4.5) | 4.0 (3.4, 4.7) | p < 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

| Fatigue scores for patients with fatigue | |||||

| Usual care | 6.2 (5.8, 6.6) | 3.5 (3.0, 4.1) | 4.0 (3.4, 4.5) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| Intervention | 5.9 (5.7, 6.2) | 5.2 (4.9, 5.6) | 4.5 (4.2, 4.9) | p < 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

0–10 scale: 0 = none, 10 = worse.

Impact of intervention on barriers to pain and fatigue management

There were significant immediate and sustained effects of the intervention on all BQII subscales except for the Communication subscale, and on the Total score (Table 3). Fatalism as a barrier to pain management actually increased in the usual care group at one month, and returned significantly to baseline at 3 months.

Table 3.

Barriers to Pain X (95% CI) from the BQ-II

| Baseline | 1 month | 3 month | Immediate Effect (Baseline to 1 Month) | Sustained or delayed effect (Baseline 1 Month to 3 Months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiologic subscales | |||||

| Usual Care | 2.3 (2.0, 2.6) | 2.4 (2.1, 2.8) | 2.1 (1.8, 2.5) | p = 0.037 | |

| Intervention | 1.8 (1.7, 2.1) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

| Fatalism subscale | |||||

| Usual care | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.1) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | p = 0.010 | |

| Intervention | 1.3 (1.0, 1.5) | 0.88 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.81 (0.6, 1.0) | p = 0.006 | p = 0.002 |

| Communication subscale | |||||

| Usual care | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) | 0.96 (0.7, 1.2) | ||

| Intervention | 1.2 (0.9, 1.4) | 0.92 (0.7, 1.2) | 0.87 (0.6, 1.1) | ||

| Harmful subscale | |||||

| Usual care | 2.5 (2.1, 2.9) | 2.5 (2.1, 2.9) | 2.3 (1.9, 2.7) | ||

| Intervention | 2.1 (1.8, 2.4) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.7) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| Total score | |||||

| Usual care | 2.0 (1.7, 2.2) | 2.2 (1.9, 2.5) | 1.8 (1.5, 2.1) | p = 0.003 | |

| Intervention | 1.7 (1.5, 1.9) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

1–5 scale: 1 = low barriers, 5 = high barriers.

BQ-IJ, Barriers Questionnaire II.

There was a significant immediate effect of the intervention on the Sensory and Cognitive subscales and for the Total Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS) score, as shown in Table 4. The p value for the Affective subscale's immediate effect did not achieve the required criterion of p = 0.0125 to control for inflation of alpha. Significant delayed improvements were shown in the usual care group for the Sensory, Affective, and Behavioral subscales and the Total score. Significant sustained effects were observed in the intervention group for the Sensory, Affective, Cognitive, and Behavioral subscales and the Total score. Significant immediate and sustained effects were shown on the Fatigue Barriers Scale (FBS) for the intervention group, as shown in Table 5. Persistent barriers to fatigue management are also listed in Table 5, as are four beliefs that were significantly improved.

Table 4.

Piper Fatigue Scale X (95% CI)

| Baseline | 1 Month | 3 Month | Immediate effect | Sustained or delayed effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory subscale | |||||

| Usual care | 6.4 (5.8, 6.9) | 6.2 (5.6, 6.7) | 5.1 (4.5, 5.7) | p < 0.001 | |

| Intervention | 6.2 (5.9, 6.5) | 5.6 (5.2, 5.9) | 4.9 (4.5, 5.2) | p < 0.001 | p = 0.002 |

| Affective subscale | |||||

| Usual care | 6.0 (5.4, 6.5) | 5.7 (5.1, 6.2) | 4.9 (4.3, 5.4) | p = 0.005 | |

| Intervention | 5.8 (5.4, 6.1) | 5.3 (4.9, 5.6) | 4.9 (4.5, 5.2) | p = 0.049 | p < 0.001 |

| Cognitive subscale | |||||

| Usual care | 4.9 (4.4, 5.4) | 4.9 (4.4, 5.4) | 4.3 (3.8, 4.8) | ||

| Intervention | 4.9 (4.6, 5.2) | 4.4 (4.1, 4.7) | 4.2 (3.9, 4.5) | p = 0.004 | p = 0.001 |

| Behavioral subscale | |||||

| Usual care | 6.0 (5.4, 6.6) | 5.7 (5.1, 6.4) | 4.9 (4.3, 5.5) | p = 0.01 | |

| Intervention | 5.4 (5.0, 5.8) | 5.0 (4.6, 5.4) | 4.5 (4.1, 4.9) | p = 0.033 | |

| Total score | |||||

| Usual care | 5.8 (5.3, 6.3) | 5.6 (5.1, 6.1) | 4.8 (4.3, 5.3) | p = 0.002 | |

| Intervention | 5.5 (5.2, 5.8) | 5.0 (4.7, 5.4) | 4.5 (4.3, 4.9) | p = 0.006 | p = 0.001 |

Range, 0–10; 0 = none, 10 = worse.

Table 5.

Barriers to Fatigue X (95% CI) from the Fatigue Barriers Scale (FBS)

| Baseline | 1 month | 3 month | Immediate effect | Sustained or delayed effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | |||||

| Usual care | 28.1 (24.9, 31.3) | 28.4 (25.6, 31.3) | 27.5 (24.9, 30.1) | ||

| Intervention | 27.5 (25.6, 29.5) | 23.9 (22.2, 25.6) | 23.8 (22.3, 25.4) | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

| Items with persistent barriers to fatigue (>3, range 0–5) Fatigue is inevitable result of cancer If fatigue is important, my MD will bring up the subject |

|||||

| Items with lower barriers to fatigue ( <1, range 0–5) If I complain, my MD won't want to treat me MD think of fatigue only as a psychological problem Talking about fatigue is as important as having my vital signs taken MD is too busy to worry about my fatigue |

|||||

15 items on a 0–5 scale. Scale range = 0–75; 0 = no barriers, 75 = maximum barriers.

Impact of intervention on knowledge of pain and fatigue management

There was a significant immediate and sustained effect on knowledge of pain for the intervention group (p < 0.001), with no significant change in knowledge of pain in the usual care group. Table 6 lists the knowledge items with persistently low scores that indicate areas of need for teaching reinforcement with patients. There are also four items that appear to have been successfully taught to patients, indicating that progress is being made in overcoming these barriers.

Table 6.

Patient Knowledge of Pain

| Overall Score = 74% to 85% correct Items with low scores ( < 60% correct) Cancer is most common cause of pain Taking opioids leads to addiction |

| Items with high scores (>90% correct) Pain is divided into 2 types: acute and chronic It is important for MDs and RNs to know about your pain Pain scale is used to describe how much pain you are feeling Fluids, exercise, fiber, and laxatives can prevent constipation as a side effect of pain medications |

| Patient knowledge of fatigue |

| Overall score = 87% to 91% correct |

| Items with low scores (<60% correct) Exercise requires more energy and leads to more effort to do activities |

| Items with high scores (>90% correct) Fatigue can be described using 0–10 scale If fatigue is severe, MD should be notified It is important to talk to MD about pain, nausea, or depression because they make fatigue worse |

The intervention group demonstrated an immediate and sustained significant effect on knowledge of fatigue and its management (p < 0.001, p = 0.002, respectively) whereas there was no significant change in knowledge for the usual care group. Table 6 lists the knowledge items with persistently low scores indicating continued need to teach and reinforce with patients. There are also three items that appear to have been successfully taught to patients, indicating that patients had some increased knowledge of fatigue.

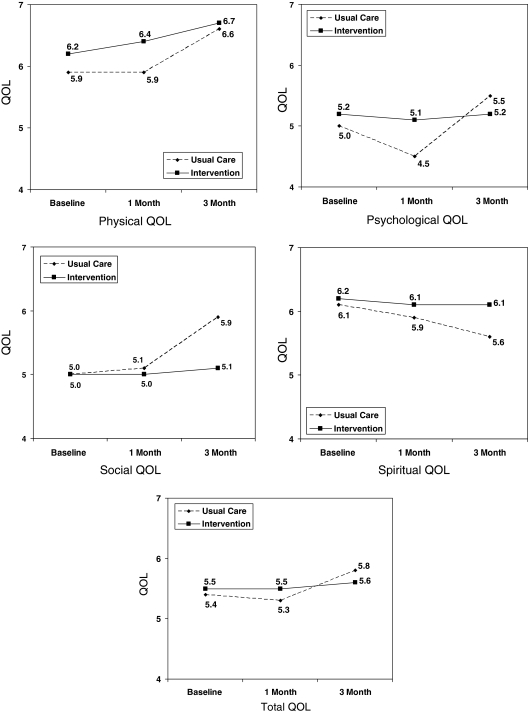

Impact of intervention on quality of life

Table 7 summarizes the four-dimensional COH-QOL tool results for the study patients. There was a significant immediate drop in Psychological QOL for the usual care group, while there were sustained improvements in Physical, Psychological, Social, and Total QOL in that group. The intervention group demonstrated a significant delayed effect in Physical QOL. Descriptively, the intervention group tended to maintain baseline levels of QOL throughout the study, or to show mild improvements (as in Physical QOL) when we would normally expect a decrease in QOL. Overall, QOL was about mid-range for these patients (5–6 on a 0–10 scale). The most frequent QOL concerns were sleep, sexuality, appetite, constipation, nausea, anxiety, depression, and isolation.

Table 7.

Quality of Life X (95% CI)

| Baseline | 1 month | 3 month | Immediate effect | Sustained or delayed Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | |||||

| Usual care | 5.9 (5.6, 6.2) | 5.9 (5.5, 6.2) | 6.6 (6.2. 6.9) | p = 0.001 | |

| Intervention | 6.2 (6.0, 6.4) | 6.4 (6.1, 6.6) | 6.7 (6.5, 6.9) | p = 0.005 | |

| Psychologic | |||||

| Usual care | 5.0 (4.6, 5.4) | 4.5 (4.2, 4.9) | 5.5 (5.1, 5.8) | p = .005 | p < 0.001 |

| Intervention | 5.2 (4.9, 5.4) | 5.1 (4.8, 5.3) | 5.2 (5.0, 5.5) | ||

| Social | |||||

| Usual care | 5.0 (4.5, 5.4) | 5.1 (4.6, 5.5) | 5.9 (5.5, 6.3) | p = 0.014 | |

| Intervention | 5.0 (4.7, 5.2) | 5.0 (4.6, 5.2) | 5.1 (4.8, 5.3) | ||

| Spiritual | |||||

| Usual care | 6.1 (5.6, 6.6) | 5.9 (5.5, 6.4) | 5.6 (5.1, 6.0) | p = 0.014 | |

| Intervention | 6.2 (5.9, 6.5) | 6.1 (5.8, 6.4) | 6.1 (5.8, 6.4) | ||

| Total QOL | |||||

| Usual care | 5.4 (5.1, 5.7) | 5.3 (5.0, 5.6) | 5.8 (5.5, 6.1) | p < 0.001 | |

| Intervention | 5.5 (5.3, 5.7) | 5.5 (5.3, 5.7) | 5.6 (5.5, 5.8) | ||

Range, 0–10; 0 = poor QOL, 10 = best QOL.

Items with low QOL scores: initial diagnosis distress, distress from treatment, family distress, uncertainty.

QOL, quality of life.

Discussion

In this study, we tested the “Passport to Comfort” intervention that targeted patient, professional, and system-related barriers to improve pain and fatigue management in an ambulatory care setting with primarily palliative care patients. Study results underscore the importance of integrating quality palliative care into routine care in order to impact symptom and QOL for patients with incurable cancer. Not only was the intervention innovative and feasible, but study results suggests that significant improvements were seen in barriers and knowledge of pain and fatigue, and that the effect was sustained over time. Although significant differences were seen on QOL measures, these differences were small, with only mild improvements observed.

The intervention was able to reduce common patient-related barriers to pain, as demonstrated by the immediate and sustained effect seen in all but one subscale score. For pain knowledge, we saw significant improvements in several communication items, including the importance to discuss pain with M.D./R.N. and the use of the pain rating scale to communicate pain intensity. Although improvements were seen in patient's willingness to discuss pain issues with health care professionals, more efforts may be needed for the importance of symptom communication between patient and provider. We also found that addiction persists as an important barrier to optimal pain management for patients with cancer. This finding indicates that aggressive education and counseling to dispel the myth of pain medication addiction may not be enough to eliminate this barrier. Future studies may need to focus on other factors that impact patient's beliefs and attitudes about pain medication. In terms of fatigue, approximately 50% of our patients reported experiencing moderate to severe fatigue. This finding validates existing evidence that fatigue is one of the most common symptoms experienced by cancer patients.48 We were able to improve knowledge on several communication items, indicating that patients are aware of the importance of discussing fatigue issues with their providers. However, patients are unaware of the importance of exercise in managing CRF. We found that patients believed that exercise expenses rather than increases energy. This belief is not supported by the current evidence that physical activity, including exercise, is an effective strategy for managing CRF.49–53 Future studies need to address this important misconception.

We had anticipated that the intervention would result in significant improvements in overall QOL for our patients. Although we were able to detect some positive changes, these changes were mild. This may not be surprising given that our sample consisted primarily of palliative care cancer patients with advanced disease. The evidence on QOL in advanced disease suggests that it is common to see gradual and sometimes dramatic QOL decline, referred to as the “terminal drop.”54 Based on these observations, some investigators proposed the “longitudinal terminal decline QOL model.” In the model, slow and steady changes in symptom distress, functional status, and QOL dimensions can occur.55 This gradual decline was also observed in our sample population, with mild improvements seen for the intervention group. Although this mild improvement in QOL may not be significant, we were able to detect improvements in our sample of patients with advanced disease where QOL decline is expected. This indicates that our intervention did have a positive impact on overall QOL.

FIG. 1.

Longitudinal quality of life (QOL).

There are several strengths and limitations of this study. Our sample consisted of four solid tumor diagnoses, which makes the study findings generalizable to more than one cancer diagnosis population. We were also able to recruit 36% ethnic minorities for study participation. Our recruitment strategy was to enroll patients who had symptomatic pain and fatigue that is moderate to severe. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable for patients who are less symptomatic.

It is relevant to discuss how the “Passport to Comfort” intervention can be integrated into routine clinical practice. The study design incorporated a third phase, where dissemination of the intervention into routine care was undertaken at the study institution. Phase 3 dissemination incorporated strategies for systems-related changes to facilitate further improvements in pain and fatigue management (Table 8). Patient education materials used in the intervention were refined and translated into Spanish. Patient education materials were made available system-wide through the employee Intranet (available to the public at http://prc.coh.org/). Advocacy posters were posted in ambulatory clinics and waiting rooms as a reminder to both patient and provider to discuss pain and fatigue-related issues. The 0–10 numeric analogue scale was added to the ambulatory clinic vital sign flow sheet to assess fatigue.

Table 8.

Patient/Professional/System Changes at City of Hope Resulting from the Barriers Study

| Patient | Professional | System |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Patient education materials developed for pain (pain assessment and management, constipation) and fatigue (fatigue assessment and management, sleep, nutrition, energy conservation, exercise) | 1. Pain and fatigue education provided to physicians, nursing, pharmacy, rehabilitation, nutrition, case management (total of 38 in-services) | 1. Routine fatigue assessment added to outpatient clinic vital sign flow sheet. |

| 2. All patient education materials translated in Spanish by COH Patient-Family Education Department. Available at: http://prc.coh.org/pt-familyEd.asp | 2. Pain and fatigue education presented at key meetings:—Medical Oncology Staff-11—Medical Grand Rounds-1—Psycho-Oncology Grand Rounds-2—Science of Caring Lecture-1 | 2. Internal Advisory Board meeting held quarterly to coordinate institution-wide efforts to improve pain and fatigue management. Average attendance per meeting 12–15 people from 10 departments. |

| 3. All patient education materials placed on COH employee internet website to be accessed by all staff and all clinics. Above efforts resulted in distribution of 1055 patient education cards throughout COH over two years. | 3. Clinical feedback reports completed for 118 patients and provided to MDs and NPs based on chart audits with specific suggestions for pain and fatigue management. | 3. Increased referrals to supportive care departments for pain and fatigue including nutrition, rehabilitation and pain/palliative care. |

| 4. Advocacy posters for pain and fatigue posted in every clinic room, in the hallways, and on the walls of the MedOnc outpatient clinic. Also posted in the hematology outpatient clinics. |

COH, City of Hope.

Finally, plans are underway to disseminate the intervention into other community cancer centers. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NCI have long emphasized the importance of disseminating evidence-based interventions into routine clinical practice, and federal funding mechanisms have been established to encourage and solicit hypothesis-driven proposals to test the dissemination process of evidence-based interventions. The investigators have submitted a proposal to test the dissemination process of the “Passport to Comfort” intervention, and if funded, our evidence-based clinical intervention to reduce barriers to pain and fatigue management can be successfully integrated into routine palliative care.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA115323).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Brawley OW. Smith DE. Kirch RA. Taking action to ease suffering: Advancing cancer pain control as a health care priority. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:285–289. doi: 10.3322/caac.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyle N. In their own words: Seven advanced cancer patients describe their experience with pain and the use of opioid drugs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobsen R. Moldrup C. Christrup L. Sjogren P. Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management: A systematic exploratory review. Scand J Caring Sci Mar. 2008;23:190–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun VC. Borneman T. Ferrell B. Piper B. Koczywas M. Choi K. Overcoming barriers to cancer pain management: An institutional change model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green CR. Montague L. Hart-Johnson TA. Consistent and breakthrough pain in diverse advanced cancer patients: A longitudinal examination. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:831–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edrington J. Sun A. Wong C, et al. Barriers to pain management in a community sample of Chinese American patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:665–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliver DP. Wittenberg-Lyles E. Demiris G. Washington K. Porock D. Day M. Barriers to pain management: Caregiver perceptions and pain talk by hospice interdisciplinary teams. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duignan M. Dunn V. Perceived barriers to pain management. Emerg Nurse. 2009;16:31–35. doi: 10.7748/en2009.02.16.9.31.c6848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi Q. Wang XS. Mendoza TR. Pandya KJ. Cleeland CS. Assessing persistent cancer pain: A comparison of current pain ratings and pain recalled from the past week. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Clinical Practice Guideline for Cancer Pain Management. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleeland CS. The impact of pain on the patient with cancer. Cancer. 1984;54(11 Suppl):2635–2641. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841201)54:2+<2635::aid-cncr2820541407>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duggleby W. Enduring suffering: A grounded theory analysis of the pain experience of elderly hospice patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27:825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward SE. Goldberg N. Miller-McCauley V, et al. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain. 1993;52:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90165-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rustoen T. Gaardsrud T. Leegaard M. Wahl AK. Nursing pain management: A qualitative interview study of patients with pain, hospitalized for cancer treatment. Pain Manag Nurs. 2009;10:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue Y. Schulman-Green D. Czaplinski C. Harris D. McCorkle R. Pain attitudes and knowledge among RNs, pharmacists, and physicians on an inpatient oncology service. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:687–695. doi: 10.1188/07.cjon.687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrell BR. Grant M. Ritchey KJ. Ropchan R. Rivera LM. The pain resource nurse training program: A unique approach to pain management. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8:549–556. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(93)90084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCaffery M. Ferrell B. O'Neil-Page E. Lester M. Ferrell B. Nurses' knowledge of opioid analgesic drugs and psychological dependence. Cancer Nurs. 1990;13:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCaffery M. Ferrell BR. Pasero C. Nurses' personal opinions about patients' pain and their effect on recorded assessments and titration of opioid doses. Pain Manag Nurs. 2000;1:79–87. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2000.9295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott TE. Elliott BA. Physician attitudes and beliefs about use of morphine for cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7:141–148. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(06)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott TE. Murray DM. Elliott BA, et al. Physician knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management: A survey from the Minnesota cancer pain project. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:494–504. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00100-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrell B. Virani R. Grant M. Vallerand A. McCaffery M. Analysis of pain content in nursing textbooks. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:216–228. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabow MW. Hardie GE. Fair JM. McPhee SJ. End-of-life care content in 50 textbooks from multiple specialties. JAMA. 2000;283:771–778. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr E. Barriers to effective pain management. J Perioper Pract. 2007;17:200–208. doi: 10.1177/175045890701700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dowden S. McCarthy M. Chalkiadis G. Achieving organizational change in pediatric pain management. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:321–326. doi: 10.1155/2008/146749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger AM. Update on the state of the science: Sleep-wake disturbances in adult patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:E165–177. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E165-E177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofman M. Ryan JL. Figueroa-Moseley CD. Jean-Pierre P. Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: The scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):4–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ancoli-Israel S. Moore PJ. Jones V. The relationship between fatigue and sleep in cancer patients: A review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2001;10:245–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Jong N. Courtens AM. Abu-Saad HH. Schouten HC. Fatigue in patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: A review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25:283–297. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200208000-00004. quiz 298–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nail LM. Fatigue in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:537. doi: 10.1188/onf.537-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institutes of Health. Symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue. 2002. http://consensus.nih.gov/ta/022/022_statement.htm. [Jan 6;2011 ]. http://consensus.nih.gov/ta/022/022_statement.htm

- 31.Payne JK. The trajectory of fatigue in adult patients with breast and ovarian cancer receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:1334–1340. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.1334-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stone P. Richardson A. Ream E. Smith AG. Kerr DJ. Kearney N. Cancer-related fatigue: Inevitable, unimportant and untreatable? Results of a multi-centre patient survey. Cancer Fatigue Forum. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:971–975. doi: 10.1023/a:1008318932641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curt GA. Impact of fatigue on quality of life in oncology patients. Semin Hematol. 2000;37(4 Suppl 6):14–17. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(00)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glaus A. Crow R. Hammond S. A qualitative study to explore the concept of fatigue/tiredness in cancer patients and in healthy individuals. Support Care Cancer. 1996;4:82–96. doi: 10.1007/BF01845757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant M. Golant M. Rivera L. Dean G. Benjamin H. Developing a community program on cancer pain and fatigue. Cancer Pract. 2000;8:187–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.84012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nail LM. Long-term persistence of symptoms. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2001;17:249–254. doi: 10.1053/sonu.2001.27916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visser MR. Smets EM. Fatigue, depression and quality of life in cancer patients: How are they related? Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s005200050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogelzang NJ. Breitbart W. Cella D, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: Results of a tripart assessment survey. The Fatigue Coalition. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 Suppl 2):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winningham ML. Nail LM. Burke MB, et al. Fatigue and the cancer experience: the state of the knowledge. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994;21:23–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allard P. Maunsell E. Labbe J. Dorval M. Educational interventions to improve cancer pain control: A systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2001;4:191–203. doi: 10.1089/109662101750290227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis D. O'Brien MA. Freemantle N. Wolf FM. Mazmanian P. Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282:867–874. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miaskowski C. Dodd M. West C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a self-care intervention to improve cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1713–1720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward SE. Wang KK. Serlin RC. Peterson SL. Murray ME. A randomized trial of a tailored barriers intervention for Cancer Information Service (CIS) callers in pain. Pain. 2009;144:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yates JW. Chalmer B. McKegney FP. Evaluation of patients with advanced cancer using the Karnofsky performance status. Cancer. 1980;45:2220–2224. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800415)45:8<2220::aid-cncr2820450835>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunnarsdottir S. Donovan HS. Serlin RC. Voge C. Ward S. Patient-related barriers to pain management: The barriers questionnaire II (BQ-II) Pain. 2002;99:385–396. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Adult Cancer Pain. 2009. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf. [Oct 6;2009 ]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf

- 47.Piper BF. Dibble SL. Dodd MJ. Weiss MC. Slaughter RE. Paul SM. The revised Piper Fatigue Scale: Psychometric evaluation in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:677–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cella D. Lai JS. Chang CH. Peterman A. Slavin M. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94:528–538. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barsevick AM. Newhall T. Brown S. Management of cancer-related fatigue. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(5 Suppl):21–25. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.S2.21-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Nijs EJ. Ros W. Grijpdonck MH. Nursing intervention for fatigue during the treatment for cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:191–206. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305721.98518.7c. quiz 207–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dimeo FC. Thomas F. Raabe-Menssen C. Propper F. Mathias M. Effect of aerobic exercise and relaxation training on fatigue and physical performance of cancer patients after surgery. A randomised controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:774–779. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iop A. Manfredi AM. Bonura S. Fatigue in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: An analysis of published studies. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:712–720. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobsen R. Sjogren P. Moldrup C. Christrup L. Physician-related barriers to cancer pain management with opioid analgesics: A systematic review. J Opioid Manage. 2007;3:207–214. doi: 10.5055/jom.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diehr P. Lafferty WE. Patrick DL. Downey L. Devlin SM. Standish LJ. Quality of life at the end of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwang SS. Chang VT. Fairclough DL. Cogswell J. Kasimis B. Longitudinal quality of life in advanced cancer patients: Pilot study results from a VA medical cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00641-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]