Abstract

Pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) may develop with long-term antibiotic administration, but is rarely reported to be caused by antitubercular agents. We present a case of PMC that occurred 120 days after starting rifampicin. A 74-year-old man was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and started on a standard HERZ regimen (isoniazid, ethambutol, rifampicin, pyrazinamide). After 4 months of HERZ, he presented with frequent bloody, mucoid, jelly-like diarrhea and lower abdominal pain. Sigmoidoscopy revealed multiple whitish plaques with edematous mucosa that were compatible with PMC. Biopsies from these lesions showed ulcer-related necrotic and granulation tissue. We stopped antitubercular treatment and started the patient on oral metronidazole. His symptoms completely resolved within 2 weeks. Antitubercular treatment was restarted by replacing rifampicin with levofloxacin. The patient did not present with diarrhea or bloody stool throughout the rest of treatment.

Key Words: Pseudomembranous colitis, Rifampicin, Tuberculosis

Introduction

Pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) is characterized by the presence of yellow or white plaques on the mucosal surface that are composed of inflammatory exudates [1]. PMC is associated with the administration of antibiotics that alter the normal gastrointestinal flora and allow overgrowth of Clostridium difficile. The frequency of this complication varies among antibacterial agents [2], and it is rarely associated with antitubercular agents.

Isoniazid and ethambutol have few effects on intestinal flora, but rifampicin has antibiotic effects over a wide range of bacteria [3] and therefore may cause PMC when PMC develops in association with antitubercular treatment. Here, we document a case of PMC that developed 4 months after initiation of rifampicin administration.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis via an abnormal chest X-ray and acid fast bacilli sputum smear (fig. 1). Antitubercular agents, including isoniazid (400 mg/day), rifampicin (600 mg/day), pyrazinamide (1,500 mg/day), and ethambutol (800 mg/day) were administered. Four months after initiation of antitubercular treatment, the patient complained of intermittent loose stool, tenesmus, and lower abdominal discomfort. Fifteen days later, his diarrhea became bloody and mucoid with a jelly-like appearance, and he suffered from aggravating lower abdominal discomfort. By the time the patient presented to our hospital, he was experiencing bloody diarrhea 5 to 6 times per day.

Fig. 1.

A chest radiograph taken at admission demonstrates whitish patch consolidations on the right upper lung field suggesting pulmonary tuberculosis. The right middle and lower lung fields are also involved with patch consolidations but show much less whitish patches than those of the right upper lung field. Contrasting to the right lung field, the left lung field does not show abnormal findings. There are no vascular abnormalities and no bony thorax abnormalities.

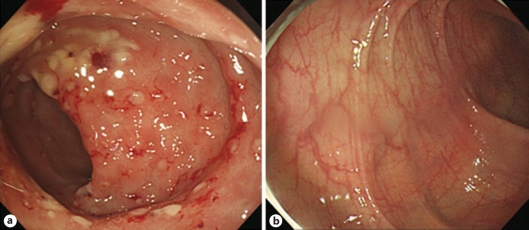

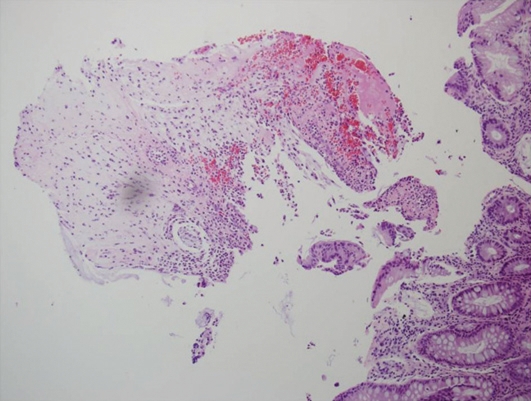

On physical examination, the patient was febrile, and his vital signs were within normal limits. His bowel movements were very frequent and his abdomen was soft and flat. Tenderness was noticed in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen without rebound tenderness. The patient's white blood cell count was 5,300/mm3, but serum C-reactive protein and erythrocyte segmentation rate were markedly elevated at 4.41 mg/dl and 57 mm/h, respectively. Sigmoidoscopy revealed multiple yellowish plaque lesions from the rectum to the sigmoid colon (fig. 2a), and mucosal biopsy from the sigmoid colon showed small collections of neutrophils between crypts at the summit of the mucosa with tufts of damaged surface epithelium (fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

a Sigmoidoscopy demonstrates multiple whitish to yellowish plaques, 5 to 8 mm in size. Many whitish to yellowish plaques are aggregated with much exudate and some fresh blood or scattered on the whole sigmoid colon. Multiple hyperemic erosive lesions are also scattered on the whole sigmoid colon with edematous mucosa. b Sigmoidoscopy, after 2 weeks of metronidazole treatment, shows that the multiple whitish to yellowish plaques and accompanied small erosions, responsible for bleeding, have disappeared completely. Pinkish mucosa with fine normal vascular patterns, which is not observed in a due to edema, is observed.

Fig. 3.

Pathologic findings reveal innumerous neutrophils aggregated and infiltrated between superficial crypts at the surface of the colonic mucosa. Infiltration of aggregated neutrophils induces distension and damage of superficial crypts. Fragments of damaged surface epithelium are also observed with much mucus material and numerous red blood cells. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, ×200.

The patient was diagnosed with PMC. We discontinued antitubercular agents and started oral metronidazole 250 mg twice per day with intravenous fluid and electrolytes. The patient's symptoms ameliorated slowly over 2 weeks of metronidazole treatment, during which he completely recovered from diarrhea, tenesmus, and abdominal pain. We restarted antitubercular agents, replacing rifampicin with levofloxacin. The patient experienced no recurrence of diarrhea by the end of antitubercular treatment, and his general condition recovered. Follow-up sigmoidoscopy did not show any evidence of PMC (fig. 2b).

Discussion

Rare cases of rifampicin-associated PMC have been reported since the 1980s [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Among antitubercular agents, rifampicin has been implicated as a cause of PMC due to its relatively wide range of antibiotic effects, whereas isoniazid and ethambutol have few effects on the intestinal flora [3]. Most C. difficile strains are susceptible to rifampicin [8], but resistance can develop after prolonged use [9]. The best method to ascertain whether PMC is induced by rifampicin consists of retrial with a single regimen of rifampicin and observation of recurrence. However, we did not retry rifampicin because our patient was elderly and in poor general condition due to his prolonged illness. We achieved a successful result after replacing rifampicin with levofloxacin, which suggests that rifampicin was responsible for PMC in our patient, although this was not confirmed bacteriologically.

In most patients with PMC, diarrhea occurs after 5 to 10 days of antibiotic administration [10]. However, as shown in table 1, rifampicin-associated PMC may occur 7 to 240 days (mean 56.6 days) after the initiation of rifampicin administration. Our patient developed diarrhea 120 days after initiating rifampicin. A long latency period is not unusual in rifampicin-associated PMC. Symptoms usually improve under treatment with vancomycin or metronidazole, and one patient was reported to recover after treatment with lactic acid bacilli only [3].

Table 1.

Characteristics of reported patients with rifampicin-associated pseudomembranous colitis

| Case | Age (years), sex | Tuberculosis | Liver disorder | Other condition | Other anti-Tbc drugs | Latency to Sx development | Manifestation | Endoscopic findings | Pathologic diagnosis | C. difficile, toxin | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 59, F | miliary | liver damage by RFP | Candida infection | INH, M | 20 | F, D, J | firm rectal mucosa | yes | ND | VCM, cholestyr-amine |

| 2 | 57, M | kidney | INH, EB | 7 | P, D, F, H, T | edema, patchy purpura/pseudomembranes | (−, ND) | none | |||

| 3 | 60, M | meninx | not mentioned | INH, EB | 28 | D | typical of PMC | yes | (+, −) | VCM | |

| 4 | 56, F | lung | alcoholic LC | INH, M, SM | 32 | F, D, P | hyperemic mucosa, pseudomembranes | yes | (−, ND) | VCM | |

| 5 | 65, F | pleura, skin | INH | 240 | D, P, T | pseudomembranes | yes | ND | VCM | ||

| 6 | 18, F | lung | not mentioned | INH, EB, SM | 38 | D, P | pseudomembranes | yes | (+, +) | cholestyramine | |

| 7 | 64, F | miliary | miliary tuberculosis | INH, EB | 26 | F, P, D | not mentioned | yes | (+, ND) | VCM | |

| 8 | ?, M | EB, SM | 70 | NA | (−, −) | NA | |||||

| 9 | 18, M | lung | INF, PZ | 17 | D, P, V, F, Pe | mild inflammation | yes | (+, +) | surgery | ||

| 10 | 52, F | lung | INF, PZ | 21 | F, P, D | friable mucosa, ulceration | yes | (−, +) | MNZ | ||

| 11 | 60, M | lung | INH | 120 | D | consistent with PMC | yes | (+, ND) | MNZ | ||

| 12 | 86, F | lung | HT, IHD | INH, EB, PZ | 112 | P, D | typical of PMC | yes | (ND, −) | VCM | |

| 13 | 58, F | lung, pleura, AIH (LC) | INH, EB | 60 | D, H, P, F | aphthoid lesions/pseudomembranes | yes | (−, ND) | lactic acid bacteria | ||

| 14 | 77, M | pleura | INH, EB, PZ | 10 | D, T | consistent with PMC | yes | (−, +) | VCM | ||

| 15 | 50, F | lung | DM | INH, EB, PZ | 56 | D, P, T | consistent with PMC | yes | (−, −) | MNZ | |

| 16 | 90, M | lung | INH, EB, PZ | 45 | D, H, P, T | consistent with PMC | yes | (−, −) | MNZ | ||

| 17 | 70, M | lung | INH, EB, PZ | 20 | D, P | consistent with PMC | yes | ND | |||

| 18 | 66, F | intestine | DM, HT | INH, EB, PZ | 60 | P | patch, pseudomembranes | yes | (+, −) | MNZ | |

| 19 | 32, F | lung | INH, EB, PZ | 30 | P, D | edema, hyperemic mucosa | yes | (+, −) | MNZ | ||

| Our patient | 74, M | lung | DM, HT | INH, EB, PZ | 120 | D, H | friable mucosa, pseudomembranes | yes | ND | MNZ | |

AIH = Autoimmune hepatitis; C. difficile = Clostridium difficile; D = diarrhea; DM = diabetes mellitus; EB = ethambutol; F = fever; H = hematochezia; HT = hypertension; IHD = ischemic heart disease; INF = interferon; INH = isoniazid; J = jaundice; LC = liver cirrhosis; M = myambutol; MNZ = metronidazole; NA = not available; ND = not determined; P = pain; Pe = perforation; PMC = pseudomembranous colitis; PZ = pyrazinamide; RFP = rifampicin; SM = streptomycin; Sx = symptom; T = tenesmus; Tbc = tuberculosis; V = vomiting; VCM = vancomycin.

Oral therapy with metronidazole 250 mg, 4 times per day for 10 days, is the recommended first-line therapy for PMC. A regimen of vancomycin, 125 to 500 mg, 4 times per day for 10 days, should be limited to patients who cannot tolerate or have not responded to metronidazole, or administered in the context of metronidazole-resistent organisms such as enterococci [11]. The yeast Saccharomyces boulardii has been shown in controlled trials to reduce recurrences when given as an adjunct to antibiotic therapy [12].

Clinicians who are managing aged, tuberculosis-infected patients must keep in mind the possibility of antitubercular agent-associated PMC and should remember that rifampicin-associated PMC has a wide range of latency periods, 1 week to 8 months after the initiation of rifampicin administration.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License (www.karger.com/OA-license), applicable to the online version of the article only. Distribution for non-commercial purposes only.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kelly CP, Pothoulakis C, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile colitis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:257–262. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401273300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shellito PC. Pseudomembranous colitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1059. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204163261605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakajima A, Yajima S, Shirakura T, Ito T, Kataoka Y, Ueda K, Nagoshi D, Kanemoto H, Matsuhashi N. Rifampicin-associated pseudomembranous colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:299–303. doi: 10.1007/s005350050350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fournier G, Orgiazzi J, Lenoir B, Dechavanne M. Pseudomembranous colitis probably due to rifampicin. Lancet. 1980;1:101. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prigogine T, Potvliege C, Burette A, Verbeet T, Schmerber J. Pseudomembranous colitis and rifampicin. Chest. 1981;80:766–767. doi: 10.1378/chest.80.6.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaui H, Leuenberger P. Pseudomembranous colitis due to rifampicin. Lancet. 1981;2:1294. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung SW, Jeon SW, Do BH, Kim SG, Ha SS, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH, Cha SI. Clinical aspects of rifampicin-associated pseudomembranous colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:38–40. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31802dfaf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbut F, Decre D, Burghoffer B, Lesage D, Delisle F, Lalande V, Delmee M, Avesani V, Sano N, Coudert C, Petit JC. Antimicrobial susceptibilities and serogroups of clinical strains of clostridium difficile isolated in France in 1991 and 1997. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2607–2611. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boriello SP, Jones RH, Phillips I. Rifampicin-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Br Med J. 1980;281:1180–1181. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6249.1180-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaHatte L, Tedesco F, Schuman B. Antibiotic-associated injury to the gut. In: Haubrich WS, Schaffner F, Berk JE, editors. Bockus Gastroenterology. ed 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995. pp. 1657–1671. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surawicz CM, McFarland LV. Pseudomembranous colitis: Causes and cures. Digestion. 1999;60:91–100. doi: 10.1159/000007633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee S, Lamont JT. Non-antibiotic therapy for Clostridium difficile infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2000;13:215–219. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]