Abstract

Tissue transglutaminase (TG2) is a widely distributed, protein-crosslinking enzyme having a prominent role in cell adhesion as a β1 integrin co-receptor for fibronectin. In bone and teeth, its substrates include the matricellular proteins osteopontin (OPN) and bone sialoprotein (BSP). The aim of this study was to examine effects of TG2-mediated crosslinking and oligomerization of OPN and BSP on osteoblast cell adhesion. We show that surfaces coated with oligomerized OPN and BSP promote MC3T3-E1/C4 osteoblastic cell adhesion significantly better than surfaces coated with the monomeric form of the proteins. Both OPN and BSP oligomer-adherent cells showed more cytoplasmic extensions than those cells grown on the monomer-coated surfaces indicative of increased cell connectivity. Our study suggests a role for TG2 in promoting the cell adhesion function of two matricellular substrate proteins prominent in bone, tooth cementum and certain tumors.

Keywords: transglutaminase 2, protein crosslinking, oligomerization, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein, osteoblast, adhesion

Introduction

Cell adhesion and cell-matrix communication is mediated by cell surface receptors including integrins that bind to matrix proteins containing cell adhesion sequences such as the tripeptide Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD).1,2 The RGD sequence is found in many noncollagenous matrix proteins such as fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, fibrinogen, fibrillin, thrombospondin, vitronectin and others.1,2 Integrins engage in bidirectional signaling where ligands outside the cell mediate signals to the inside of the cell (outside-in signaling) and where intracellular events lead to specific activation of integrins on the cell surface. A hallmark of integrin activity is their clustering into focal contacts at the periphery of cells, which in turn brings together a number of signaling molecules whose interactions initiate signaling cascades.1,2 Integrin activity is facilitated by many cellular macromolecules, including transmembrane proteoglycans and transglutaminase 2, which can potentiate signaling activity.3–5

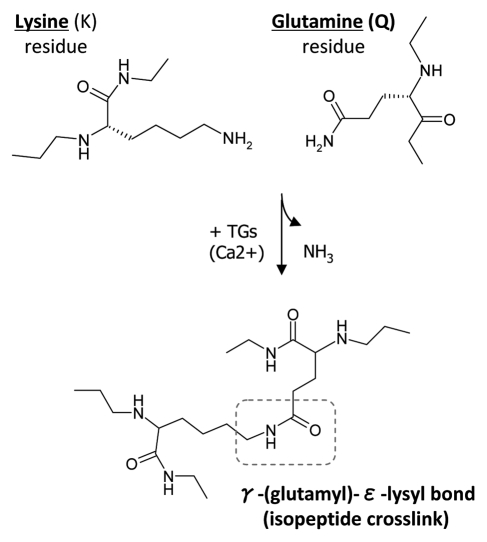

Transglutaminase 2 (tissue TG, TGc) is a protein-crosslinking enzyme which catalyzes the formation of a covalent, γ-(glutamyl)-ε-lysyl bond between specific lysine (K) and glutamine (Q) residues of its substrate proteins (Fig. 1).6–9 This enzymatic action can stabilize individual proteins and protein-protein interactions and protein networks, and it can generate high-molecular weight protein oligomers. Many RGD-containing matrix proteins have been identified as TG-substrates including fibronectin, nidogen, laminin and thrombospondin.10–12 TG2 is ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues, has a widespread distribution and is implicated in ECM stabilization, cell adhesion, wound healing and apoptosis.6–9 TG2 is predominantly found in the cytoplasm of cells, but it has also been observed at the plasma and nuclear membranes. Although TG2 lacks the hydrophobic signal sequence characteristic of secreted proteins, it has been localized extracellularly at the cell surface.13–21 TG2 is known to accumulate in focal adhesions and to act as a β1 and β3 integrin binding co-receptor for fibronectin (FN).4 Several groups have studied TG2 in focal adhesions where it is thought to facilitate cell adhesion and signaling by promoting integrin clustering via complexation with FN or by converting soluble FN to insoluble fibrils.13–21 Integrin clustering by TG2 promotes RhoA activation. TG2 also incorporates itself into the protein oligomers that it creates,22 and high-molecular weight TG2 have been observed on cell surfaces.4 We have recently demonstrated that TG2-mediated polymerization/oligomerization of FN significantly increases its osteoblast adhesive properties and enhances β1-integrin clustering, which further underscores the importance of a functional relationship between TG2 and FN.22

Figure 1.

Transglutaminase-mediated crosslinking and the formation of γ-(glutamyl)-ε-lysyl bond. TGs catalyze a transferase reaction between the γ-carboxamide group of a protein-bound glutamine (Q) residue and the ε-amino group of a protein-bound lysine (K) residue or other free or bound primary amine. The result of this post-translational modification is a covalent, irreversible γ-(glutamyl)-ε-lysyl bond, also described as an isopeptide crosslink.

We and others have demonstrated that in addition to FN, TG2 can also mediate oligomerization of certain members of the SIBLING (Small Integrin-Binding Ligand N-linked Glycoprotein) family of proteins3–29 that include osteopontin (OPN), bone sialoprotein (BSP), dentin phosphoprotein (DPP), dentin sialoprotein (DSP), dentin matrix protein-1 (DMP1) and matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE).30 SIBLING proteins are all secreted matricellular proteins containing abundant post-translational modifications and an RGD cell adhesion motif.30,31 All SIBLING proteins also possess the ability to bind to the mineral phase (a substituted hydroxyapatite) of bones and teeth and, although they are highly abundant in mineralized tissues,32 they are also linked to tumor metastasis and cancer progression.31 OPN in particular has a prominent role in inflammatory and wound healing processes.33

We have shown that both monomeric and oligomeric forms of OPN and BSP are found in bone.27 OPN has two transgluta-minase-reactive glutamines (Q34 and Q36),24 and treatment with TG2 generates high molecular weight OPN oligomers.23–26 OPN oligomerization induces a more ordered conformational structure as measured by circular dichroism and results in increased collagen binding.26 Moreover, both OPN and TG2 have been co-localized with αvβ3 integrin, suggesting that oligomeric OPN might similarly function as a high-molecular weight cell attachment molecule in its binding to integrins.34 The cell adhesion properties of BSP have also been shown to promote enhanced osteoblastic cell differentiation and cancer cell survival by activating integrin-mediated signaling.35,36 Very little is known about the role of OPN and BSP oligomerization in terms of effects on protein function. Since TG2 is expressed in bone by osteoblasts,27,37–39 it is likely that oligomerization of both OPN and BSP is relevant to their function. A recent report suggests that oligomerization of OPN promotes endothelial and carcinoma cell line attachment to the protein complex.40 Furthermore, we have shown that FN exhibits enhanced osteoblast adhesion properties after oligomerization by TG2,22 and that TG-activity in osteoblast cultures is required for osteoblast differentiation.38 The purpose of this study is to ascertain whether oligomerization of OPN and BSP also enhances cell adhesion function. In this study, we show that surface-immobilized and oligomerized OPN and BSP have significantly increased cell adhesion properties, promoting cell adhesion and contact with the surface and promoting the formation of long cellular extensions.

Results

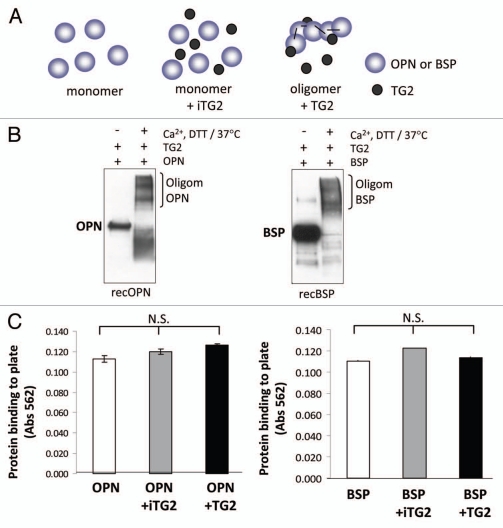

The goal of this study was to examine if two TG2 substrates, OPN and BSP, would have altered cell-adhesion properties upon oligomerization by TG2 crosslinking. Rat recombinant OPN and BSP were oligomerized in a TG2 incubation and success of the process was assessed by western blotting. As shown in Figure 2B, a 2 h incubation with TG2 enzyme results in abundant oligomer formation for both proteins. The molecular weights of the oligomers ranged between 150 and 250 kDa, with OPN having three different bands possibly representing dimers, trimers and tetramers. BSP had similarly sized faint bands at the expected levels for dimer and trimer formation. Monomeric recombinant OPN and BSP, although having a mass of 33 kDa, are both detected between 60–70 kDa. This well-known anomalous migration is a result of the abundance of acidic residues in these proteins. The origins of the lower-molecular weight OPN bands (below 50 kDa) appearing after TG2 incubation are unknown, although it can be speculated to be attributable to internal crosslinking within OPN monomers, which could induce a tighter structure and results in a faster migration on SDS-PAGE.

Figure 2.

Oligomerization of rat recombinant OPN and BSP for cell adhesion assays. (A) Schematic representation of samples used in the cell adhesion study. (B) Western blot analysis of rat recombinant OPN and BSP before and after incubation with TG2. Proteins were detected with LF-123 and LF-100 antibodies (courtesy of Dr. Larry W. Fisher, NIDCR). (C) Protein coating efficiency of OPN and BSP samples. Proteins were coated onto 96-well microplates overnight at 4°C and the protein binding to the surface was assessed by BCA reagent followed by measured optical density at 562 nm. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between protein binding to surfaces were not significant (N.S.).

To analyze the cell adhesion properties of these oligomers, we analyzed (a) monomeric protein, (b) monomer mixed with inactive TG2 and (c) polymers generated by a 2 h incubation with active TG2 as depicted in Figure 2A. Protein samples were coated onto 96-well plate surfaces where all samples bound with essentially equal efficiency (Fig. 2C). There were also no major differences between the level of OPN vs. BSP binding to the surfaces indicating that similar amounts of both proteins were immobilized. The amount of TG2 protein used to induce cross-links was low and hence was not a significant contributor to the total protein content detected in the protein-bound wells.

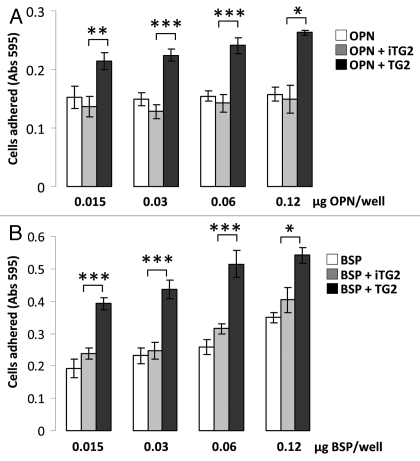

MC3T3-E1 cell adhesion to the oligomerized OPN and BSP and controls was tested over a 2 h adhesion period followed by crystal violet staining of the fixed, surface-bound cells. Figure 3 shows that both monomer OPN and BSP support cell adhesion, and that oligomerization significantly increases this activity. The increase in the number of cells adhering to the proteins after oligomerization was 1.6-fold higher for BSP and 1.7-fold higher for OPN (average of all the concentrations tested). BSP in general was more efficient than OPN in supporting cell adhesion resulting in an approximate 2-fold increase in cell attachment for both monomer and oligomer preparations in comparison to OPN. This is not a result of protein coating differences since both proteins had similar coating efficiencies.

Figure 3.

MC3T3-E1/C4 cell adhesion on OPN- and BSP-coated surfaces. Microplates (96-well) were coated with protein samples. Wells were blocked with BSA and serum starved MC3T3-E1/C4 cells were plated to the wells at a density of 4 × 104 cells/well and left to adhere for 2 h. After adherence, wells were washed vigorously until no cells remained on the BSA-coated surface. This was monitored by light microscopy. Cells were then fixed and stained with crystal violet stain.

(A) Cell adhesion to OPN. (B) Cell adhesion to BSP. Error bars represent SEM. *p > 0.1, **p > 0.01, ***p > 0.001.

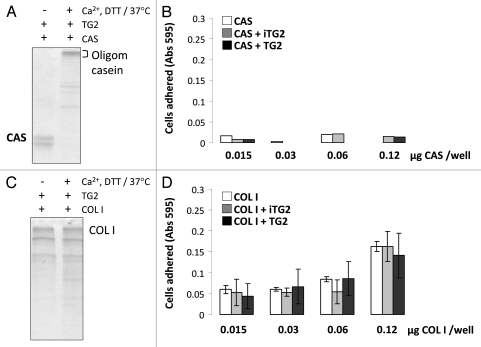

As a control, we next performed experiments to determine whether any TG2-treated substrate protein would have similar cell adhesion properties after crosslinking and oligomerization. For this we used casein, which is a known TG2 substrate but which does not have an RGD sequence. As shown in Figure 4A and B, casein forms abundant oligomers after TG2 incubation, but does not support cell adhesion either in its monomeric or oligomeric forms. In contrast, while collagen type I promotes cell adhesion, TG2 treatment did not cause significant oligomerization and there was no increase in cell binding after treatment (Fig. 4C and D).

Figure 4.

MC3T3-E1/C4 cell adhesion on TG2-incubated casein- and collagen type I-coated surfaces: Protein samples were coated onto 96-well plates and blocked with BSA. Serum starved cells were plated at a density of 4 × 104/well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Wells were washed until negative control BSA-well had no cells left, after which cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. After washes, stain was solubilized in 1% SDS and color was measured at 595 nm with a microplate reader. (A) Cell adhesion to casein (CAS) samples. (B) Cell adhesion to collagen type I (COL I) samples. Error bars represent SEM. *p > 0.1, **p > 0.01, ***p > 0.001.

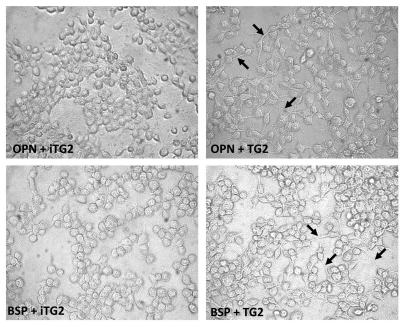

The cells bound to the monomer or oligomer OPN and BSP preparations were examined by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 5) to assess their adherent morphologies. Readily apparent was the difference in cell morphology adherent to the oligomeric OPN and BSP as compared to the monomeric proteins. Oligomer-bound cells did not appear more spread, but exhibited more filopodia/cytoplasmic extensions, whereas cells on the monomer proteins were rounder with no protruding cellular extensions. Collectively, our results demonstrate that TG2-mediated oligomerization is a protein modification capable of significantly promoting the cell adhesion properties of its matricellular substrates.

Figure 5.

Phase-contrast micrographs of MC3T3-E1/C4 cells on OPN and BSP protein-coated surfaces. MC3T3-E1/C4 cells were allowed to adhere for 2 h on monomeric and oligomeric FN, OPN and BSP and fixed with glutaraldehyde. Black arrows indicate filopodia/cytoplasmic extensions.

Discussion

TG2, a fibronectin-binding coreceptor for β1-integrin and a protein crosslinking enzyme, has been strongly linked to cell adhesion of normal and cancerous cells.4,13–21 Although its co-receptor function does not appear to require crosslinking activity,15 many reports have linked FN oligomerization to TG2-mediated crosslinking.16,18,19 Furthermore, TG2 itself is found as a high-molecular weight form on the cell surface indicating that some level of covalent oligomerization or complexation could have occurred.4,15 Also, we and others have shown that TG2-oligomerized FN when immobilized onto a surface possesses increased cell adhesion properties and an ability to promote integrin clustering compared to monomeric FN.22

In this study, we show that two other matricellular proteins that are substrates for TG2, OPN and BSP, have increased cell adhesion properties after oligomerization by TG2. Furthermore, the oligomerization appears to promote the formation of cellular extensions indicating that the cells are in better contact with this surface than when plated onto monomer-bound surfaces. We have previously shown that in bone, TG2 localizes to the osteoid layer (unmineralized bone matrix), on the osteoblast surface and in the pericellular matrix of osteocytes.27 OPN and BSP are most prominently found within the mineralized matrix—produced by osteoblasts and osteocytes—indicating that these could be the sites that may contain significant levels of TG2-oligomerized proteins.43–45 Electron microscopy and high-resolution immunogold labeling have demonstrated that in extracellular matrix related to osteocytes OPN is localized to a thin, noncollagenous surface-coating structure termed the lamina limitans often found exactly at the osteocyte-mineralized matrix interface when no intervening unmineralized matrix is present.44 It is therefore reasonable to consider that in the context of cell adhesion, OPN oligomerization in bone could be related to maintaining osteocyte adhesion to surrounding matrix that is heavily mineralized and perhaps to promoting formation of cellular extensions such as observed in our work here. Whether cells in our experiments had increased cell-cell adhesion or cell-cell communication is unknown. Although BSP has not been specifically reported to be pericellular by EM immunogold staining,43 these negative findings do not preclude its presence there; negative staining of BSP at those sites could arise from changes in conformation, crosslinking or degradative processing that could render epitopes inaccessible to the antibodies used. The fact that BSP has an RGD sequence, as has OPN, clearly implies a cell-adhesion function.46,47 Although it is clear that TG2 is around the osteocytes, it is not known whether it is on the cell surface of osteocytes or is secreted into the pericellular or bulk bone matrix.27 Some reports indicate that TG2 is only released to the matrix from the cytosolic compartment upon cell injury and rupture, which suggests that it is not in the extracellular matrix under normal situations.48 While our previous TG2 immunolocalization results in mouse tissues indicates that TG2 is found in the unmineralized matrix of bone, our recent cell culture work builds on this by suggesting that TG2 could be released outside the cells as a cleaved form having only ATPase activity and no transglutaminase activity.27,49 However, osteoblasts also express a second transglutaminase, FXIIIA,38,39,50 which is known to crosslink FN and OPN23,51 and amongst other matrix proteins. Similar to TG2, FXIIIA is also found in osteoid, osteoblasts and in the pericellular matrix of osteocytes50 and could contribute to crosslinking of OPN and BSP. Several reports have suggested that TG2 and FXIIIA, which share many substrates,23,51 could have a synergistic function and could compensate for each other under deficiency conditions in knockout models.38,39,52 Indeed, it was recently shown that the lack of skeletal phenotype in TG2 knockout mouse is due to compensation from FXIIIA.52 Therefore, OPN and BSP oligomerization in bone could be jointly orchestrated by the two enzymes; TG2 on the cell surface and FXIIIA in the extracellular matrix.

The mechanism by which oligomerization of OPN abd BSP promotes cell adhesion remains unknown. Of note, however, may be the observations by circular dichroism that OPN oligomers exhibit more ordered secondary structure as compared to OPN monomers,26 and that TG2-crosslinked FN is more resistant to unfolding in denaturing solutions.53 Since OPN and BSP are intrinsically disordered, flexible proteins,54–58 inducing more order could potentiate the function of some domains. In related experiments it was shown that BSP binding to type I collagen enhances its mineral-nucleating potency59 implying that interactions of BSP can potentiate its function perhaps by inducing stability to its structure. Similarly, in this study, TG2-mediated BSP crosslinking enhanced its cell adhesion properties. While further studies are needed, we can speculate that enhancement of cell adhesion after oligomerization may be caused by better exposure to the cells of the RGD sites, and that multiple RGD sites brought into close proximity by TG-mediated crosslinking might allow for integrin clustering and enhanced cell adhesion.

Oligomerization could also expose cryptic non-RGD cell adhesion sequences which have been shown to exist for both OPN and BSP.60–62 For example, thrombin cleavage of OPN reveals a binding site for α9β1 integrin,61 and non-RGD containing BSP fragments generated by chymotrypsin digestion have cell adhesion properties.62 Interestingly, it has been recently demonstrated that TG2 modification of OPN generates a new α9β1-binding site, which facilitates its function in neutrophil chemotaxis.63 Whether this is the same cell adhesion site that is revealed by thrombin cleavage is not known. A further possibility as to how TG2 could potentiate protein function is that the effect is mediated partly by TG2 itself as part of its incorporation into the oligmeric complexes along with its substrates. In this manner, TG2 could promote the stability of its substrates and act as a bridge to enhance substrate binding to integrins, the latter idea having been proposed by the Belkin group for FN and β1-integrin.4,15 Thus, TG2 could act as an enhancer molecule for matrix-cell interactions which would also include other adhesive proteins. Although the work from Belkin's group clearly demonstrates that cell surface TG2 does not require crosslinking activity for its cell adhesive function, our present study shows that treating OPN and BSP with inactive TG2 is not sufficient to enhance cell adhesion. However, it is noted that the role of TG2 in FN-mediated adhesion could be different than OPN and BSP-mediated adhesion.

Another possibility is that TG-mediated crosslinking of proteins induces not only structure but also increases molecular rigidity which has been demonstrated to be a major regulator of cell function in a number of studies.64–68 Cell adhesion and integrin function are enhanced on rigid versus soft surfaces, with rigidity promoting tension between cells and their environment. Indeed, we have shown by atomic force microscopy nano-indentation experiments that crosslinked FN (having enhanced cell adhesion properties) has a higher Young's modulus and rigidity compared to non-crosslinked FN.53

Regardless of mechanism of action, it is nonetheless evident that TGs can modify cell-matrix constituents and that protein oligomerization could be an important step in the functionalization of cell adhesion proteins. In fact, oligomerization could serve as a secondary enhancing step, that upon initial cellular adherance to a substratum permits a subsequent increase in cell adhesion and further potentiates and/or initiates signaling cascades. Thus, TG2 crosslinked cell adhesion proteins could serve as additional enhancers to TG2 where it is used in biomaterials and tissue enginering applications including as functional surface coatings or as agents that aid in generating three-dimentional scaffolds for cells to adhere and to grow upon.69,70 In vivo, this modification of OPN can have important implications to its function in bone healing where OPN highly is abundant on cell-matrix interfaces.44

Materials and Methods

Preparation of protein oligomers.

Rat recombinant OPN and BSP proteins were prepared in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) which was transformed by OPN and BSP expression plasmids described elsewhere.41,42 Oligomerization of rat recombinant OPN and BSP was performed as described previously by us for FN.22,27 Briefly, proteins (2 µg) were incubated with 2 mU of TG2 (guinea pig liver, Sigma), in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, containing 3 mM calcium chloride (CaCl2) and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C. Controls for oligomerized proteins included: (1) OPN or BSP monomer in buffer; (2) OPN or BSP with TG2 in buffer lacking Ca2+ and DTT and incubated at 4°C thus preventing enzyme activation. This sample was referred to as OPN or BSP + iTG2 (inactive TG2). Figure 2A depicts the three samples. Confirmation of OPN and BSP oligomerization was assessed by western blotting as previously described.27,28 Antibodies for OPN and BSP detection were LF-123 and LF-100, respectively, both kind gifts from Dr. L.W. Fisher (NIDCR, Bethesda, MD). Casein (Sigma) and rat tail collagen type I (Sigma) were used as additional control proteins and incubated with TG2 as above. The modification status after incubation of both control proteins was visualized by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining.

Protein coating efficacy.

For cell adhesion assays, protein preparations were incubated in 96-well Costar cell culture plates overnight at 4°C after which unbound proteins were removed by washing. To ensure that both monomer and oligomer protein mixtures adhered equally to the dishes being used, protein binding was assessed by adding 150 µl of water and 150 µl of bicinchonic acid reagent (BCA, Pierce) and incubating the mixtures in the wells for 2 h at 60°C. 300 µl of the supernatant was transferred to another microplate well and the absorbance at OD 562 nm was read reflecting the bound protein content in the original coated well.

Cell adhesion assay.

Cell adhesion assays were performed as described previously.22 Briefly, serial dilutions of monomeric or oligomeric OPN and BSP (prepared as above), with concentrations up to 1 µg/well were coated on the surface of a 96-well microplate (Costar) and left to adhere overnight at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the wells blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 2 h at 21°C. Meanwhile, MC3T3-E1/C4 cells, a pre-osteoblastic cell line, were serum-starved for 1 h, trypsinized and re-suspended in serum-free, complete modified alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM) at 4 × 105 cells per ml. The BSA was removed from the wells and 100 µl containing 4 × 104 cells were added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 2 h. All the wells were washed vigorously with serum-free α-MEM until cells were removed from the negative control (wells coated with BSA alone); the removal of the cells was monitored by light microscopy between each washing step. The cells were then fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 20% methanol in PBS by shaking the plates for 20 min at room temperature. The solution was removed and the wells washed and dried for 10 min. The cell-bound stain was dissolved by incubating the wells with 1% SDS overnight in the dark. The optical density was read at 595 nm with a microplate reader. To assess cell morphology, the wells were fixed as above and maintained in 5% sodium azide (NaN3) azide at 4°C and visualized by phase-contrast microscopy.

Statistical analysis.

Error in experiments is expressed as standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments done in triplicates. Statistical significance was assessed using Student's t-test from Microsoft Excel software and p values are as follows: *p > 0.1, **p > 0.01, ***p > 0.001.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants to M.T.K. and H.A.G. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. M.T.K. is a scholar of the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec.

Abbreviations

- TG2

transglutaminase 2

- iTG2

inactive transglutaminase 2

- FN

fibronectin

- OPN

osteopontin

- BSP

bone sialoprotein

- FXIIIA

factor XIIIA

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CAS

casein

- COL I

collagen type I

References

- 1.Barczyk M, Carracedo S, Gullberg D. Integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:269–280. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0834-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan MR, Humphries MJ, Bass MD. Synergistic control of cell adhesion by integrins and syndecans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:957–969. doi: 10.1038/nrm2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akimov SS, Krylov D, Fleischmann LE, Belkin AM. Tisue transglutaminase is an integrin-binding adhesion coreceptor for fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:825–838. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telci D, Wang Z, Li X, Verderio EA, Humphries MJ, Baccarini M, et al. Fibronectin-tissue transglutaminase matrix rescues RGD-impaired cell adhesion through syndecan-4 and beta1 integrin co-signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;25:20937–20947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801763200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aeschlimann D, Thomazy V. Protein crosslinking in assembly and remodelling of extracellular matrices: the role of transglutaminases. Connec Tissue Res. 2000;41:1–27. doi: 10.3109/03008200009005638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fesus L, Piacentini M. Transglutaminase 2: an enigmatic enzyme with diverse functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:534–539. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorand L, Graham RM. Transglutaminases: crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrm1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iismaa SE, Mearns BM, Lorand L, Graham RM. Transglutaminases and disease: lessons from genetically engineered mouse models and inherited disorders. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:991–1023. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Achyuthan KE, Rowland TC, Birckbichler PJ, Lee KN, Bishop PD, Achyuthan AM. Hierarchies in the binding of human factor XIII, factor XIIIa and endothelial cell transglutaminase to human plasma fibrinogen, fibrin and fibronectin. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;162:43–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00250994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aeschlimann D, Paulsson MJ. Cross-linking of laminin-nidogen complexes by tissue transglutaminase. A novel mechanism for basement membrane stabilization. Biol Chem. 1991;266:15308–15317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch GW, Slayter HS, Miller BE, McDonagh J. Characterization of thrombospondin as a substrate for Factor XIII. J Biol Chem. 262:1772–1778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueki S, Takagi J, Saito Y. Dual functions of transglutaminase in novel cell adhesion. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2727–2735. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.11.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heath DJ, Downes S, Verderio E, Griffin M. Characterization of tissue transglutaminase in human osteoblast-like cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1477–1485. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akimov SS, Belkin AM. Cell-surface transglutaminase promotes fibronectin assembly via interaction with the gelatin-binding domain of fibronectin: a role in TGFβ-dependant matrix deposition. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2989–3000. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verderio E, Nicholas B, Gross S, Griffin M. Regulated expression of tissue transglutaminase in swiss 3T3 fibroblasts: effects on the processing of fibronectin, cell attachment and cell death. Exp Cell Res. 1998;239:119–138. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaudry CA, Vederio E, Aeschlimann D, Cox A, Smith C, Griffin M. Cell surface localization of tissue transglutaminase independent on a fibronectin-binding site in its N-terminal β-sandwich domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30707–30714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentile V, Thomazy V, Piacentini M, Fesus L, Davies PJ. Expression of tissue transglutaminase in Balb-C 3T3 fibroblasts: effects on cellular morphology and adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:463–474. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.2.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heath DJ, Downes S, Verderio E, Griffin M. Characterization of tissue transglutaminase in human osteoblast-like cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1477–1485. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janiak A, Zemskov EA, Belkin AM. Cell surface transglutaminase promotes RhoA activation via integrin clustering and suppression of the Src-p190PhoGAP signaling pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1606–1619. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones RA, Nicholas B, Mian S, Davies PJ, Griffin M. Reduced expression of tissue transglutaminase in a human endothelial cell line leads to changes in cell spreading, cell adhesion and reduced polymerization of fibronectin. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2461–2472. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.19.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forsprecher J, Wang Z, Nelea V, Kaartinen MT. Enhanced osteoblast adhesion on transglutaminase 2-crosslinked fibronectin. Amino Acids. 2009;36:747–753. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prince CW, Dickie D, Krumdieck CL. Osteopontin, a substrate for transglutaminase and factor XIII activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;177:1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sørensen ES, Rasmussen LK, Møller L, Jensen PH, Hørup P, Petersen TE. Localization of transglutaminase-reactive glutamine residues in bovine osteopontin. J Biochem. 1994;304:13–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3040013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaartinen MT, Pirhonen A, Linnala-Kankkunen A, Mäenpää PH. Transglutaminase-catalyzed crosslinking is inhibited by osteocalcin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22736–22741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaartinen MT, Pirhonen A, Linnala-Kankkunen A, Mäenpää PH. Transglutaminase treated osteopontin exhibits increased collagen binding properties. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1729–1735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaartinen MT, El-Maadawy S, Räsänen NH, McKee MD. Transglutaminase and its substrates in bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;12:2161–2173. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaartinen MT, Sun W, Kaipathur N, McKee MD. Transglutaminase crosslinking of SIBLING proteins in teeth. J Dent Res. 2005;84:607–612. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaartinen MT, Murshed M, Karsenty G, McKee MD. Osteopontin upregulation and polymerization by transglutaminase 2 in calcified arteries of Matrix Gla protein-deficient mice. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:375–386. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7087.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher LW, Torchia DA, Fohr B, Young MF, Fedarko NS. Flexible structures of SIBLING proteins, bone sialoprotein and osteopontin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:460–465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellahcíne A, Castronovo V, Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs): multifunctional proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:212–226. doi: 10.1038/nrc2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qin C, Baba O, Butler WT. Post-translational modifications of sibling proteins and their roles in osteogenesis and dentinogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:126–136. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morimoto J, Kon S, Matsui Y, Uede T. Osteopontin; as a target molecule for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:494–505. doi: 10.2174/138945010790980321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wozniak M, Fausto A, Carron CP, Meyer DM, Hruska KA. Mechanically strained cells of the osteoblast lineage organize their extracellular matrix through unique sited of αvβ3-integrin expression. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1731–1745. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.9.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon JA, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by bone sialoprotein regulates osteoblast differentiation. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189:138–143. doi: 10.1159/000151728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon JA, Tye CE, Sampaio AV, Underhill TM, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Bone sialoprotein expression enhances osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization in vitro. Bone. 2007;41:462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKee MD, Addison WN, Kaartinen MT. Hierarchies of extracellular matrix and mineral organization in bone of the craniofacial complex and skeleton. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;181:176–188. doi: 10.1159/000091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Jallad HF, Nakano Y, Chen JL, McMillan E, Lefebvre C, Kaartinen MT. Transglutaminase activity regulates osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization in MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cultures. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nurminskaya M, Kaartinen MT. Transglutaminases in mineralized tissues. Front Biosci. 2006;11:1591–1606. doi: 10.2741/1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higashikawa F, Eboshida A, Yokosaki Y. Enhanced biological activity of polymeric osteopontin. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2697–2701. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.da Silva AP, Ellen RP, Sørensen ES, Goldberg HA, Zohar R, Sodek J. Osteopontin attenuation of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Lab Invest. 2009;89:1169–1181. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tye CE, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Identification of the type I collagen-binding domain of bone sialoprotein and characterization of the mechanism of interaction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13487–13492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen J, McKee MD, Nanci A, Sodek J. Bone sialoprotein nRNA expresion and ultrastructural localization in fetal porcine calvarial bone: comparison with osteopontin. Histochem J. 1994;26:67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKee MD, Nanci A. Osteopontin at mineralized tissue interfaces in bone, teeth and osseointegrated implants: ultrastructural distribution and implications for mineralized tissue formation, turnover and repair. Microsc Res Tech. 1996;33:141–164. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19960201)33:2<141::AID-JEMT5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amir LR, Jovanovic A, Perdijk FB, Toyosawa S, Everts V, Bronckers AL. Immunolocalization of sibling and RUNX2 proteins during vertical distraction osteogenesis in the human mandible. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:1095–1104. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7162.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oldberg A, Franzén A, Heinegård D. The primary structure of a cell-binding bone sialoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:19430–19432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oldberg A, Franzén A, Heinegård D. Cloning and sequence analysis of rat bone sialoprotein (osteopontin) cDNA reveals an Arg-Gly-Asp cell-binding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8819–8823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegel M, Strnad P, Watts RE, Choi K, Jabri B, Omary MB, et al. Extracellular transglutaminase 2 is catalytically inactive, but is transiently activated upon tissue injury. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:1861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakano Y, Forsprecher J, Kaartinen MT. Regulation of ATPase activity of transglutaminase 2 by MT1-MMP: implications for mineralization of MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cultures. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:260–269. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakano Y, Al-Jallad HF, Mousa A, Kaartinen MT. Expression and localization of plasma transglutaminase factor XIIIA in bone. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:675–685. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7091.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barry ELR, Mosher DF. Factor XIII cross-linking of fibronectin at cellular matrix assembly sites. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10464–10469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarantino U, Oliva F, Taurisano G, Orlandi A, Pietroni V, Candi E, et al. FXIIIA and TGFbeta overexpression produces normal musculo-skeletal phenotype in TG2-/- mice. Amino Acids. 2009;36:679–684. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nelea V, Nakano Y, Kaartinen MT. Size distribution and molecular association of plasma fibronectin and fibronectin crosslinked with transglutaminase 2. Protein J. 2008;27:223–233. doi: 10.1007/s10930-008-9128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butler WT. Structural and functional domains of osteopontin. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;760:6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butler WT, Ridall AL, McKee MD. Osteopontin. In: Bilezikian JP, Raisz LG, Rodan GA, editors. Principles of bone biology. Academic Press; 1996. pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robey PG, Boskey . The biochemistry of bone. In: Marcus RD, Feldman J, editors. Osteoporosis. Academic Press; 1996. pp. 95–183. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tye CE, Rattray KR, Warner KJ, Gordon JA, Sodek J, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Delineation of the hydroxyapatite-nucleating domains of bone sialoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7949–7955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211915200. Epub 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Six genes expressed in bones and teeth encode the current members of the SIBLING family of proteins. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baht GS, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Bone sialoprotein-collagen interaction promotes hydroxyapatite nucleation. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:600–608. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Dijk S, D'Errico JA, Somerman MJ, Farach-Carson MC, Butler WT. Evidence that a non-RGD domain in rat osteopontin is involved in cell attachment. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;12:1499–1505. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650081213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith LL, Cheung H-K, Ling L, Chen J, Sheppard D, Pytela R, et al. Osteopontin N-terminal domain contains a cryptic adhesive sequence recognized by α9β1 integrin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28485–28491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mintz KP, Grzesik WJ, Midura RJ, Robey PG, Termine JD, Fisher LW. Purification and fragmentation of nondenatured bone sialoprotein: evidence for a cryptic, RGD-resistant cell attachment domain. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:985–995. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nishimichi N, Higashikawa F, Kinoh HH, Tateishi Y, Matsuda H, Yokosaki Y. Polymeric osteopontin employs integrin alpha9beta1 as a receptor and attracts neutrophils by presenting a de novo binding site. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14769–14776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901515200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choquet D, Felsenfeld DP, Sheetz MP. Extracellular matrix rigidity causes strenghtening of inegrin-cytoskeletal linkages. Cell. 1997;88:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81856-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Engler AJ, Griffin MA, Sen S, Bonneman CG, Sweeny HL, Dischler DE. Myotubes differentiate optimally on substrates with tissue-like stiffness: pathological implications for soft or stiff microenvironments. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:877–887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kostic A, Sheetz MP. Fibronectin rigidity response though Fyn and p130Cas recruitment to the leading edge. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2684–2695. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jiang G, Huang AH, Cai Y, Tanase M, Sheetz MP. Rigidity sensing at the leading edge through integrins and RPTPα. Biophys J. 2006;90:1804–1809. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Orban JM, Wilson LB, Kofroth JA, El-Kurdi MS, Maul TM, Vorp DA. Crosslinking of collagen gels by transglutaminase. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68:756–762. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arrighi I, Mark S, Alvisi M, von Rechenberg B, Hubbell JA, Schense JC. Bone healing induced by local delivery of an engineered parathyroid hormone prodrug. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1763–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]