Abstract

Despite increasing pharmaceutical importance, fluorinated aromatic organic molecules remain difficult to synthesize. Present methods require either harsh reaction conditions or highly specialized reagents, making the preparation of complex fluoroarenes challenging. Thus, the development of new and general methods for their preparation that overcome the limitations of those techniques currently in use is of great interest. We have prepared [LPd(II)Ar(F)] complexes where L is a biaryl monophosphine ligand and Ar is an aryl group, and identified conditions under which reductive elimination occurs to form an Ar-F bond. Based on these results, we have developed a catalytic process that converts aryl bromides and aryl triflates into the corresponding fluorinated arenes using simple fluoride salts. We expect this method to allow the introduction of fluorine atoms into advanced, highly functionalized intermediates.

Introduction

A large number of pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals contain fluorinated aromatic (Ar–F) groups, which enhance solubility, bioavailability, and metabolic stability compared to non-fluorinated analogs (1,2,3,4). Furthermore, radioactive 18F-labelled organic compounds are also widely used as contrast agents for positron emission tomography (PET) (5,6).

However, traditional methods for the introduction of a fluorine atom into an aromatic framework usually require harsh conditions that are incompatible with many functional groups. Such methods include direct fluorination (7), the conversion of amines via the aryldiazonium salt with HBF4 (Balz-Schiemann reaction) (8) or the nucleophilic substitution of electron-poor bromo- or chloroarenes with KF (Halex reaction) (9), as well as the more recent transformation of aryl iodides with CuF2 (10). A modified Balz-Schiemann process, of particular use for PET (11), employs aryliodonium salts that are produced under highly acidic or oxidizing conditions (12). In a recent significant advance, the Halex reaction was performed at room temperature using anhydrous tetrabutylammonium fluoride, but the substrate scope was limited, and the fluoride source is not readily amenable to the preparation of 18F-labelled compounds (13). Due to these limitations, fluorine atoms are often introduced to aromatic compounds early in synthetic sequences and prior to the introduction of significant molecular complexity, which greatly increases the difficulty of accessing target molecules.

Recently, transition-metal promoted Ar-F bond formation has been achieved with use of electrophilic “F+” reagents such as Selectfluor® or N-fluoropyridinium salts (14,15,16,17,18,19,20). These interesting reactions are believed to proceed via high-valent Pd or Ag intermediates and have been used to access highly functionalized aryl fluorides. However, these reactions have some limitations with respect to preparative chemistry. In many cases, stoichiometric amounts of the transition metal must be employed. In the reported examples that proceed with a catalytic quantity of metal, specific directing groups on the substrate are required to facilitate a C-H activation process, thus diminishing the general applicability of the methods (14,15,21). An additional drawback of this approach is that electrophilic 18F reagents are not available with high specific activity, lessening the utility of these methods for PET applications (12,22).

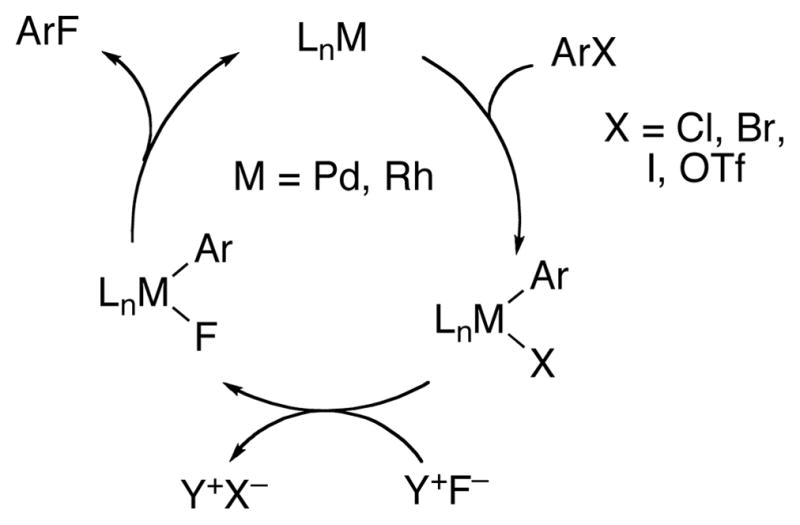

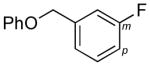

In light of the importance of fluorinated arenes and the practical limitations of current methods for their preparation, the metal-catalyzed conversion of an aryl halide or sulfonate (e.g., triflate ≡ OTf) with a nucleophilic fluorine source (such as an alkali metal fluoride) to yield the corresponding aryl fluoride is a highly desirable transformation (Fig. 1). For a process operating at reasonable temperatures and in the absence of electrophilic reagents, high functional group compatibility and a wide substrate scope might be expected. This is of particular importance in the preparation of biologically active compounds, where often late-stage modifications are key in identifying medicinal targets. In addition, such a strategy would be ideal for the preparation of PET imaging agents because mildly nucleophilic 18F− reagents, especially Cs18F, can be readily prepared.

Figure 1.

Metal Catalyzed Aryl Fluorination

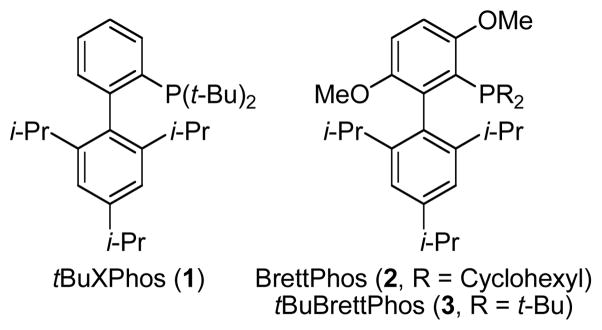

Grushin’s elegant mechanistic studies of isolated [LnMAr(F)] complexes (M = Pd, Rh) have demonstrated that reductive elimination to form an Ar-F bond is extremely challenging (22,23,24,25,26,27). These experiments have shown that undesired reaction pathways involving supporting ligands (L) and fluoride dominate the chemistry of these complexes. This is both due to the high barrier to Ar–F bond formation, as well as favorable pathways involving ligand-based P–F or C–F bond formation. In addition, the accessibility of stable [LnPdAr(F)]2 dimers has been suggested to contribute to the difficulty in achieving the desired reductive elimination (28). These results have cast doubt on whether a catalytic cycle as depicted in Figure 1 is viable. We note, however, that for the heavier halides the reductive elimination of ArX (X = Cl, Br, I) from a Pd(II) intermediate is precedented (29). In addition, it was recently shown that the dimeric Pd complex [(o-tol)3PPd(p-NO2C6H4)(F)]2 yielded 10% of para-fluoronitrobenzene upon heating in benzene in the presence of an excess of ligand 1, a ligand initially developed in our laboratories for use in C-N bond-forming reactions. Although it has been questioned whether this latter reaction proceeds via a conventional reductive elimination (30), we were intrigued by the possibility that biaryl monophosphine ligands could promote this type of difficult reductive elimination to form Ar-F bonds.

Herein, we report the preparation of a well-characterized Pd(II) complex that undergoes reductive elimination producing an aryl fluoride. Based on this result, we have developed a palladium-catalyzed method for the preparation of aryl fluorides from aryl triflates using CsF that proceeds with high functional group tolerance under mild reaction conditions.

Ar–F Reductive Elimination from a Pd(II) Complex

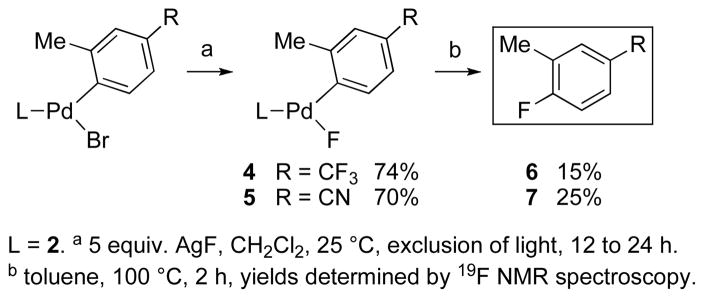

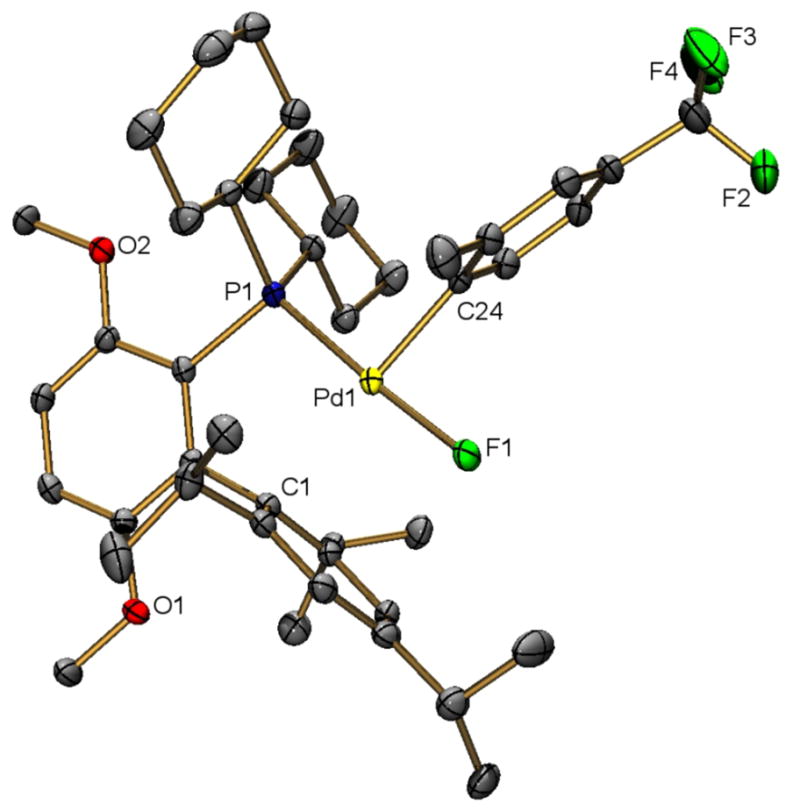

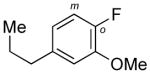

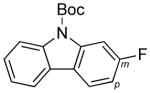

Recently, we reported a monophosphine ligand, BrettPhos (2), for use in aryl amination reactions (31). Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and crystallographic studies of [2·PdAr(X)] (X = Cl or Br) complexes revealed that they were monomeric both in solution and in the solid state. We decided to prepare analogous [2·PdAr(F)] complexes in order to determine if they were also monomeric and to see if 2 could be useful as a ligand in promoting reductive elimination to form Ar-F bonds (32). We found that these targets were best accessed by transmetalation of the [2·PdAr(Br)] complexes with AgF at room temperature in dichloromethane (Fig. 3). The isolated [2·PdAr(F)] complexes exhibit a characteristic doublet in 31P and 19F-NMR spectra with a coupling constant 2JPF of ~175 Hz, depending on the aryl group. The X-ray structure of 4 (Ar = 2-methyl-4-trifluoromethylphenyl) confirmed the monomeric nature of the complex (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Preparation of and Reductive Elimination From [2·PdAr(F)] Complexes

Figure 4. X-Ray Structure of Complex 4.

(ORTEP drawing at 50% probability, hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity)

We next examined the thermolysis of 4 and 5 at 100 °C in toluene and found that reductive elimination to form 6 and 7 occurs in yields of 15% and 25%, respectively (Fig. 3), which demonstrates that Ar–F bond formation is possible using these complexes. The yields in these reactions could be increased to 45% of 6 and 55% of 7 if the reductive eliminations were conducted in the presence of an excess of the corresponding aryl bromide. (33,34) In these cases, the 31P NMR spectra of the reaction mixtures showed that the oxidative-addition complexes [2·PdAr(Br)] were formed as the only phosphorous-containing products, suggesting LPd(0) is formed along with the ArF product.

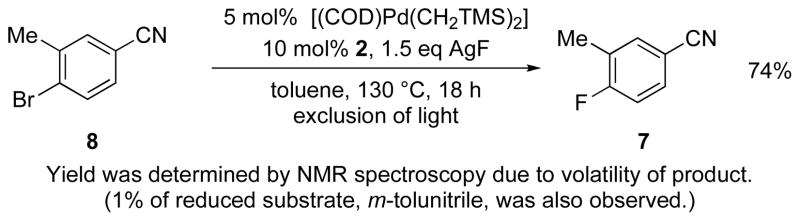

Having demonstrated that oxidative addition, halide exchange (transmetalation) and reductive elimination were all possible, we next examined the catalytic conversion of ArBr 8 to ArF 7. Upon treatment of 8 with AgF (1.5 equiv) and 10 mol% each of 2 and [(COD)Pd(CH2TMS)2] (COD = 1,5-cyclooctadiene) (35) at 110 °C for 18 h, a 52% yield of 7 was observed, which was increased to 74% after optimization of the reaction conditions (Fig. 5). No product was detected in control experiments that omitted 2 and/or the Pd precatalyst. This demonstrates that Pd-complexes supported by BrettPhos can catalyze the conversion of an aryl bromide to an aryl fluoride. However, the scope of aryl bromides that could be effectively transformed is to date limited to electron-poor substrates bearing an ortho substituent, in line with the observation that no reductive elimination took place from [2·PdAr(F)] complexes with Ar = 3,5-dimethylphenyl or Ar = 4-n-butylphenyl.

Figure 5.

Catalytic Conversion of Aryl Bromide 8 to Aryl Fluoride 7

Efficient Catalysis with Aryl Triflates

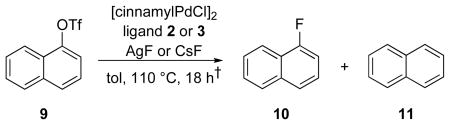

Concurrently, we also examined the use of aryl triflates as substrates. Although initial reactions of the triflate of 1-naphthol (9) provided only a trace of product 10, employing CsF in place of AgF as the fluoride source gave 10 in 30% yield (Table 1). In addition, 5% of naphthalene (11) was also observed. We also found that the readily prepared and more stable [(cinnamyl)PdCl]2 could be used as the Pd precatalyst with a similar outcome. Overall, this result is significant as it demonstrates that the fluorination can be carried out without the need to employ a stoichiometic quantity of a noble metal component while still using a nucleophilic fluoride source.

Table 1. Optimization of Aryl Triflate Fluorination.

Conversion and yield were determined by gas chromatography (GC).

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd (mol%)* | Ligand (mol%) | F− source (eq) | Conversion | 10 | 11 |

| 10 | 2 (10) | AgF (1.5) | ‡ | trace | ‡ |

| 10 | 2 (10) | CsF (1.5) | 90% | 30% | 5% |

| 10 | 3 (10) | CsF (1.5) | 100% | 71% | 1% |

| 2 | 3 (3) | CsF (2.0) | 100% | 79% | 1% |

mol% of palladium equivalents (“Pd”),

time not optimized,

not determined

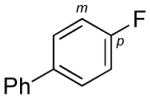

In order to optimize the Ag-free reaction, a broad range of ligands were examined; under these conditions (Table 1) only ligands closely related to 2 provided more than a trace amount of 10. (36,37) Best results were obtained using tBuBrettPhos (3) (Fig. 2) as ligand; a 71% yield of 10 was realized, with only 1% of reduction product 11 observed. Further optimization of the reaction conditions increased the yield of 10 to 79%. Since the reaction proved to be sensitive to water (38), commercially obtained CsF was dried at 200 °C under vacuum overnight and handled in a nitrogen-filled glovebox. Replacing CsF with spray-dried KF afforded 10 in 52 % yield. No reaction was observed in the absence of the catalyst, ruling out both classic SNAr and aryne mechanisms (39).

Figure 2.

Ligands for the Successful Reductive Elimination of Ar-F

We realized that for some applications, including PET, that it was necessary to have a faster process. We found that the conversion of 9 to 10, using 5 mol% [(COD)Pd(CH2TMS)2] as precatalyst, 10 mol% of 3 as supporting ligand, and 3 equivalents of CsF, was complete in 2.5 h in toluene at 110 °C, yielding 80% of 10. Increasing the amount of CsF to 6 equivalents and adding 30 mol% of the solubilizing agent poly(ethylene glycol) dimethyl ether (Me2PEG) led to full conversion in less than 30 min, albeit in yield of 71%. Similar rates of reaction could be achieved using [cinnamylPdCl]2; with 5 mol% of this palladium source and 15% ligand the reaction proceeds to completion in ≤2 hours in 79% yield (NMR). We are in the process of identifying conditions to achieve faster conversion of the substrate without diminishing the yield, as required for PET applications.

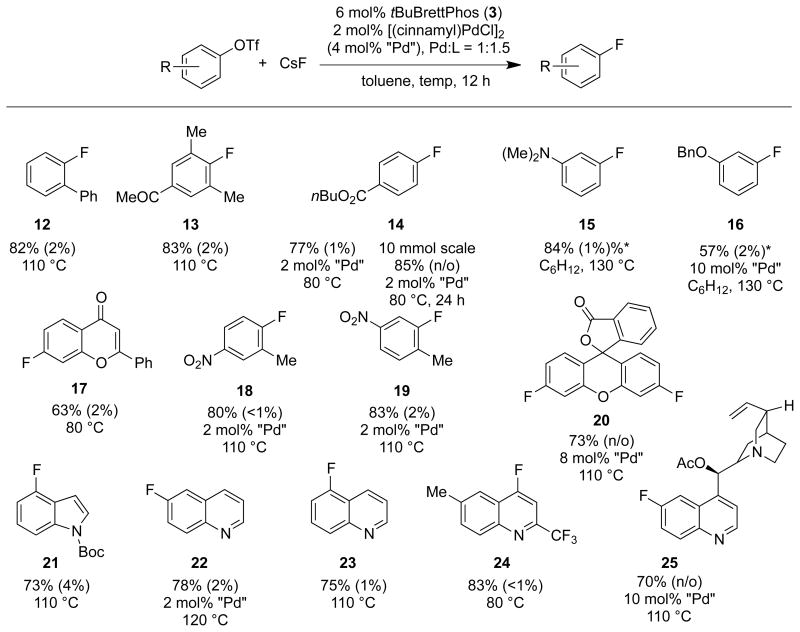

As can be seen in Table 2, the fluorination of aryl triflates has substantial scope. Simple aromatic substrates, such as ortho-biphenyl triflate, react rapidly to provide aryl fluorides in high yield. Hindered substrates such as 4-acetyl-2,6-dimethylphenyl triflate are also efficiently converted to product (13). Electron-deficient arenes can be efficiently transformed using only 2 mol% of catalyst (14, 18, 19). Importantly from a practical standpoint, a variety of heterocyclic substrates can also be successfully fluorinated using these conditions. Flavones (17), indoles (21), and quinolines (22–24) were all converted in good yield. More complex aryl triflates derived from fluorescein (20) and quinine (25) could also be effectively converted to their fluorinated analogues, demonstrating that this method can be used in the preparation of pharmaceutically relevant compounds. In some cases, product formed in high yield at 80 °C (14, 17, 24). On a 10 mmol scale, butyl 4-fluorobenzoate 14 was prepared at 80 °C with no observable formation of reduced by-product (in general, 2% or less reduction product was observed across the range of substrates screened).

Table 2. Fluorination of Aryl Triflates.

Isolated yields are an average of at least two independent reactions. Values in parentheses denote the amount of reduced starting material based on the isolated product yield (n/o = not observed). In cases with different palladium loading, the ligand amount was adjusted accordingly (Pd:L = 1:1.5).

|

Cyclohexane (C6H12) was used as a solvent to decrease the amount of reduced product.

Many functional groups are tolerated, an exception being Lewis basic groups such as amines or carbonyls in the ortho position of the aryl triflate. No reaction takes place in these instances, presumably because the basic group coordinates the Pd center, possibly preventing transmetalation. As in the Pd-catalyzed formation of Ar–O bonds, the transformation of electron-rich substrates was more challenging. We found that good yields were obtained at higher temperatures (130°C).

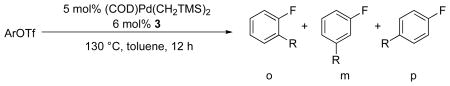

Formation of Regioisomers

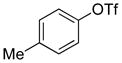

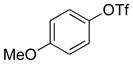

Unexpectedly, regioisomeric products were formed in a few cases (Tables 3 and 4). Since control experiments did not yield any product in the absence of catalyst, we believe that isomer formation is also a palladium-catalyzed process. Investigating a series of tolyl (26–28) and anisole (29–31) triflates, we found that for substrates 26, 27, and 29 the observed selectivities are quite distinct from those reported for a benzyne process (39) (Table 3). Experiments with 2,6-dideuterated anisole triflate 31 showed a reduced rate of formation of the undesired regioisomer while the rate of formation of the desired product remained largely unchanged, leading to a 2.5-fold increase in selectivity in comparison to the reaction with unlabelled 31. Thus, at least for this substrate, we conclude that two competing pathways are involved; it is evident that hydrogen abstraction is the rate-limiting or the first irreversible step in regioisomer formation and that little or none of the desired isomer is formed from the path that finally leads to the regioisomer.

Table 3. Regioisomers in Tolyl and Anisole Fluorination.

Chemical yields are given as the sum of ArF products. Traces of reduction products were also observed. Ratios are compared to those of a reported fluorination of bromoaryls that proceeds via a benzyne intermediate (in parentheses).(39)

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26, 42% o/m=>99:1* (57:43) |

27, 63% o/m/p=0:95:5† (26:53:21) |

28, 48% m/p=36:64† (63:37) |

29, 49% o/m=98:2* (0:100) |

30, 65% m/p=98:2* (100:0) |

31, 25% m/p=70:30* (62:38) |

Product ratios and yield determined by GC.

Product ratios and yield determined by 19F NMR Spectroscopy.

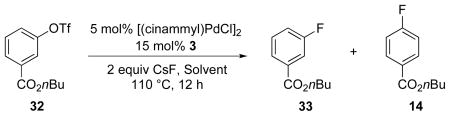

Table 4. Solvent Screen and Fluorination of Triflates That Gave Regioisomers.

Unless otherwise noted, yields and ratios determined by GC and 19F NMR.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent | conversion | combined yield | ratio 33/14 | ArH |

| Toluene | 100 | 71% | 78:22 | 2% |

| Benzene | 100 | 69% | 90:10 | * |

| THF | 95 | 18% | 78:22 | * |

| Cyclohexane | 100 | 60% | >98:2 | 1% |

| n-Heptane | 100 | 39% | 85:15 | * |

| Cyclohexane† | 100 | 80% | 99:1 | 1% |

Yield not determined.

Optimized condition 100 °C, isolated yield.

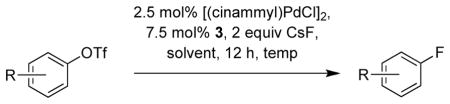

While we do not have a complete mechanistic understanding of the pathway leading to the regioisomers, we have found that the product ratio can be strongly affected by solvent polarity; the desired pathway is favored in highly apolar media. Examination of a number of solvents for the conversion of 32 to 33 revealed that the formation of the undesired isomer 14 is almost completely suppressed with use of cyclohexane (Table 4). This trend appears to be general, in most instances in which the undesired regioisomer was observed using toluene, switching to cyclohexane afforded almost exclusively the desired product. For example, fluorinated aryls 33 to 37 could be prepared with greater than 95:5 selectivity favoring the desired isomer (Table 5). This modification provides a highly practical means to minimize formation of regioisomeric byproducts.

Table 5. Use of Cyclohexane as Solvent to Surpress Formation of Regioisomers.

Desired isomer is shown. Product ratios are for regioisomeric aryl fluorides as indicated. Isolated yields are for the major isomer, with values in parentheses denoting the amount of reduced starting material based on the isolated product yield.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tol* |

34 m/p = 87:13 |

35 o/m = 77:23 |

36 p/m = 93:7 |

37 m/p = 93:7 |

| cy† |

m/p = 96:4 90% (<1%) 110 °C |

o/m = 98:2 61% (~8%) 130 °C |

p/m = >98:2 80% (3%) 100 °C |

m/p = >98:2 77% (2%) 110 °C |

2.5–5 mol% [(cinammyl)PdCl]2, 7.5–15 mol% 3, solvent = toluene.

solvent = cyclohexane.

Conclusion

In summary, starting from the observation of the reductive elimination of ArF from a [2·PdAr(F)] complex we have developed a metal-catalyzed direct conversion of aryl bromides and aryl triflates into the corresponding aryl fluorides using simple fluoride sources such as AgF and CsF. In particular, the transformation of aryl triflates exhibits a wide substrate scope and tolerates a number of functional groups, allowing for the introduction of fluorine atoms into highly functionalized organic molecules. Key to these findings was the use of the sterically demanding, electron-rich biaryl monophosphine tBuBrettPhos 3 as the supporting ligand. We believe that this ligand not only promotes reductive-elimination of the Ar–F bond due to its large size, but also prevents the formation of dimeric [LPdAr(F)]2 complexes. At present, both of these factors appear to be critical in the successful catalytic reaction. Although some limitations remain with regard to substrate scope and reaction conditions, we expect this method to be applicable to the preparation of biologically active and radiolabelled aryl fluorides.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health for financial support of this project (Grant GM46059). We thank Merck, Nippon Chemical, Boehringer Ingelheim, and BASF for gifts of chemicals and additional funds. M.S. thanks the Singapore-MIT Alliance for a Graduate Fellowship. J.G.-F. thanks the Spanish M.E.C. for a Postdoctoral Fellowship. T.K. thanks the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation for a Feodor Lynen Postdoctoral Fellowship. The Varian NMR instrument used was supported by the NSF (Grants CHE 9808061 and DBI 9729592). We also thank Dr. Peter Müller for obtaining the crystal structure of 4. CCDC 741377 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. A patent application has been filed by MIT covering portions of this work with S.L.B., D.A.W., M.S., and G.T. as co-inventors.

References

- 1.Müller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Science. 2007;317:1881. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böhm HJ, Banner D, Bendels S, Kansy M, Kuhn B, Müller K, Obst-Sander U, Stahl M. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:637. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200301023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerebtzoff G, Li-Blatter X, Fischer H, Frentzel A, Seelig A. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:676. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeschke P. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:570. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelps M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1501. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandford G. J Fluorine Chem. 2007;128:90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balz G, Schiemann G. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1927;60:1186. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finger GC, Kruse CW. J Am Chem Soc. 1956;78:6034. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grushin VV. 7,202,388. US Patent. 2007

- 11.Pike VW, Aigbirhio FI. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1995:2215. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross TL, Ermert J, Hocke C, Coenen HH. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8018. doi: 10.1021/ja066850h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun H, DiMagno SG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2720. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hull KL, Anani WQ, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7134. doi: 10.1021/ja061943k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ball ND, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3796. doi: 10.1021/ja8054595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furuya T, Kaiser HM, Ritter T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5993. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuya T, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10060. doi: 10.1021/ja803187x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furuya T, Strom AE, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1662. doi: 10.1021/ja8086664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaspi AW, Yahav-Levi A, Goldberg I, Vigalok A. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:5. doi: 10.1021/ic701722f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powers DC, Ritter T. Nature Chemistry. 2009;1:302. doi: 10.1038/nchem.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Mei TS, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7520. doi: 10.1021/ja901352k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angelini G, Speranza M, Wolf AP, Shiue CY. J Fluorine Chem. 1985;27:177. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grushin VV. Chem- Eur J. 2002;8:1006. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020301)8:5<1006::aid-chem1006>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall WJ, Grushin VV. Organometallics. 2003;22:555. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3068. doi: 10.1021/ja049844z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall WJ, Grushin VV. Organometallics. 2004;23:3343. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macgregor SA, Roe DC, Marshall WJ, Bloch KM, Bakhmutov VI, Grushin VV. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15304. doi: 10.1021/ja054506z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yandulov DV, Tran NT. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1342. doi: 10.1021/ja066930l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy AH, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1232. doi: 10.1021/ja0034592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. Organometallics. 2007;26:4997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fors BP, Watson DA, Biscoe MR, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13552. doi: 10.1021/ja8055358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Materials and methods are detailed in the Supporting Online Material available at Science Online.

- 33.The lower yield in the absence of added aryl bromide suggests that the 2·Pd(0) complex that results from reductive elimination further reacts with remaining [2·PdAr(F)] complex. Increased product yields have previously been observed in the reductive elimination of C-S bonds from Pd(II) centers when Pd0 scavengers (exogenous ligand) have been added to the reaction. See reference 34.

- 34.Mann G, Baranano D, Hartwig JF, Rheingold AL, Guzei IA. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9205. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan Y, Young GB. J Organomet Chem. 1999;577:257. [Google Scholar]

- 36.After this paper was submitted, we have found that the closely related hetero-biaryl lignad 5-(di-tert-butylphosphino)-1-(1,3,5-triphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole (Bippyphos) reported by Singer and co-workers (see reference 37 and citations therein) can also provide catalysts with moderate levels of activity for fluorination. For example, with use of 10 mol% of this ligand and 5 mol% [(cinnamyl)ClPd]2, a 52% yield of 10 along with 11% reduction product was observed after heating for 12 h at 150 °C in toluene.

- 37.Withbroe GJ, Singer RA, Sieser JE. Org Process Res Dev. 2008;12:480. [Google Scholar]

- 38.We followed the reaction of 9 to 10 by GC and found that after a brief initial period in which about 20% of 9 was consumed, 10 begins to form. By adding 20 mol% water, we observed that the initial loss of material increased to 60%. This indicates that one molecule of water consumes two molecules of 9 under the reaction conditions. Nevertheless, the reaction proceeded to give 40% 10. We believe that the initial loss of mass balance is due to formation of biaryl ether: presumably, adventitious water results in the formation of phenol, which further reacts with a second molecule of ArOTf in a Pd-catalyzed process.

- 39.Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. Organometallics. 2008;27:4825. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.