Abstract

Myeloma is characterized by the overproduction and secretion of monoclonal protein. Inhibitors of the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway (IBP) have pleiotropic effects in myeloma cells. To investigate whether IBP inhibition interferes with monoclonal protein secretion, human myeloma cells were treated with specific inhibitors of the IBP or prenyltransferases. These studies demonstrate that agents that inhibit Rab geranylgeranylation disrupt light chain trafficking, lead to accumulation of light chain in the endoplasmic reticulum, activate the unfolded protein response pathway and induce apoptosis. These studies provide a novel mechanism of action for IBP inhibitors and suggest that further exploration of Rab-targeted agents in myeloma is warranted.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, GGTase II, unfolded protein response, secretion, apoptosis

1. Introduction

Multiple myeloma, a disorder of malignant plasma cells, is characterized by the overproduction of monoclonal protein. The secreted protein may be in the form of intact antibodies or light chains and can have devastating effects on kidneys. Quantitation of the monoclonal protein in either serum or urine is used to follow the course of the disease and response to therapy. With the possible exception of allogeneic transplant, which is associated with marked morbidity and mortality, there are currently no curative strategies for this disease.

Plasma cells require the machinery necessary to to be able to rapidly produce large quantitites of antibodies. In order to support this activity, there is marked restructuring and expansion of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) during differentiation from B cells to plasma cells [1]. Conditions that disrupt ER protein folding activate the unfold protein response (UPR) pathway which coordinates protein synthesis and degradation, chaperone expression, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis [2]. There is increasing evidence for the role of the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway in both benign and malignant plasma cell biology [1,3,4]. Differentiation of B cells to plasma cells is associated with upregulation of the prosurvival components of the UPR [1]. Furthemore, the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, which is now widely used in the treatment of multiple myeloma, has been shown to induce the proapoptoic components of the UPR [4].

The aminobisphosphonate zoledronic acid (ZA) has found widespread use in the management of myeloma-induced bone disease due to its very high affinity for bone mineral and ability to inhibit osteoclast function [5]. ZA also has direct toxic effects on myeloma cells [6]. ZA and other aminobisphonates inhibit farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FDPS), an enzyme in the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway (IBP) (Figure 1A) [7,8]. Two products of the IBP, farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), play key roles as substrates for the family of protein prenyltransferases, which includes farnesyl transferase (FTase) and geranylgeranyl transferases (GGTase) I and II. That inhibition of other enzymes in the IBP, including HMG-CoA reductase [9] and GGPP synthase (GGDPS) [10] or direct inhibition of the prenyltransferases [11–13], induces cytotoxic effects in myeloma cells suggests the underlying importance of protein prenylation, particulary geranylgeranylation.

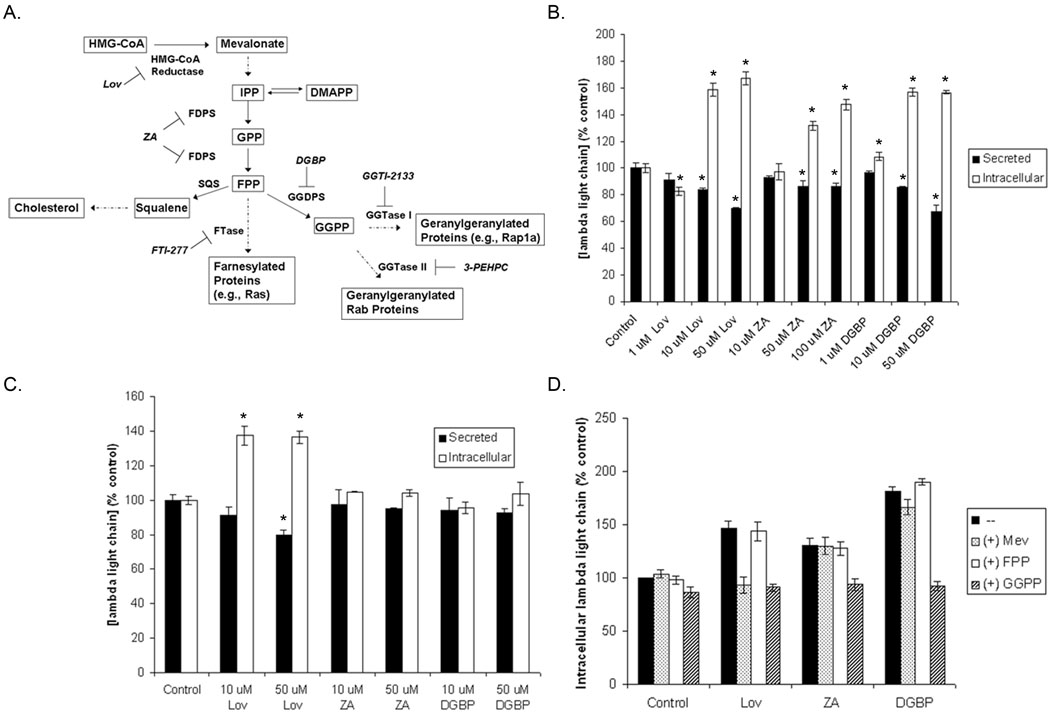

Figure 1. Inhibition of the IBP disrupts light chain secretion in human myeloma cells via depletion of GGPP.

A) The IBP and pharmacological inhibitors. RPMI-8226 (B) and U266 (C) cells were incubated with varying concentrations of lovastatin (Lov), ZA, or DGBP for 24 hours. D). RPMI-8226 cells were incubated with 10 µM Lov, 50 µM ZA, or 10 µM DGBP in the presence or absence of 1 mM mevalonate (Mev), 10 µM FPP, or 10 µM GGPP for 24 hours. Secreted and intracellular lambda light chain levels were determined via ELISA. The * denotes p<0.05 per unpaired two-tailed t-test. Data are expressed as a percentage of control (mean ± SD, n=3).

The majority of prenylated proteins belong to the Ras small GTPase superfamily (e.g., Ras, Rho, and Rab families). Rab family members play critical roles in all aspects of intracellular membrane trafficking and more than 60 Rabs have been identified in mammalian cells [14]. There is complex specificity, both with regard to organelle localization and cell type-specific expression. Studies involving mutated versions of Rabs or knock-out mice have demonstrated defects in secretion [15]. The function of Rab proteins appears to depend on proper membrane localization which is achieved through geranylgeranylation. Mutant forms of Rabs that are unable to be geranylgeranylated are mislocalized and nonfunctional [16].

There is evidence that IBP inhibition may disrupt the secretory pathway in other systems. Statins inhibit cholecystokinin secretion from endocrine cells in vitro [17] and to induce intracellular accumulation of amyloid precursor protein with decreased beta-amyloid secretion in neuroblastoma cells [18]. Simvastatin was found to decrease IgM secretion in Waldenström macroglobulinemia cell lines [19]. That this effect could be completely prevented by mevalonate and, and to a slightly lesser extent by GGPP, suggests that depletion of GGPP, and presumably inhibition of geranylgeranylation, was responsible for the observed changes in IgM secretion [19]. Given the role of geranylgeranylated Rab proteins in regulating intracellular vesicle trafficking and secretion, we hypothesized that agents which inhibit Rab geranylgeranylation will disrupt monoclonal protein secretion in myeloma cells. We demonstrate that agents which interfere with Rab geranylgeranylation, either through depletion of GGPP or direct inhibition of GGTase II, inhibit light chain secretion and lead to accumulation of light chain in the ER, activate the UPR, and induce apoptosis. These studies provide a novel mechanism of action for IBP inhibitors in multiple myeloma.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Reagents

Lovastatin (converted to the dihydroxy-open acid form prior to use), dl-mevalonic acid lactone (converted to mevalonate prior to use), farnesyl pyrophosphate, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, brefeldin A, tunicamycin, FTI-277, and GGTI-2133 were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Zoledronic acid was purchased from Novartis (East Hanover, NJ). Digeranyl bisphosphonate (DGBP) [20] was supplied by Terpenoid Therapeutics, Inc (Coralville, IA). 3-PEHPC [21] was kindly provided by Professor David Wiemer, Department of Chemistry, University of Iowa. Anti-pan-Ras was obtained from InterBiotechnology (Tokyo, Japan). Anti-β-tubulin, anti-Rap1a, anti-Rab6, anti-calnexin, anti-GRP78, anti-lambda light chain, anti-CHOP, anti-PARP, anti-PDI, anti-rat IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and anti-goat IgG HRP antibodies as well as protein A/G PLUS agarose conjugate were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-eiF2α and phospho-eiF2α antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit HRP-linked antibodies were obtained from Amersham (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). EasyTag™ EXPRESS35S Protein Labeling Mix was purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA).

2.2 Multiple myeloma cell lines

Human multiple myeloma cell lines (RPMI-8226 and U266) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), glutamine and penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

2.3 Primary myeloma cells

After informed consent, peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirate samples were obtained from patients with plasma cell malignancies. The protocol was approved by our Institutional Review Board for human subjects. Plasma cells were isolated by positive selection using the MACS Whole Blood Column with CD138 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were incubated in short term culture in RPMI medium supplemented with FCS (10%) and recombinant human IL-6 (10 ng/mL). The diagnosis of multiple myeloma or plasma cell leukemia was confirmed in all patients by hematopathologist review of bone marrow biopsy specimens and the identity of the monoclonal protein was determined by serum immunofixation electrophoresis. Patient 1 had kappa light chain myeloma, patient 2 had IgG kappa myeloma with higher relative kappa levels than IgG levels, patient 3 had IgG kappa myeloma, and patient 4 had IgG kappa plasma cell leukemia.

2.4 Monoclonal protein quantitation

Cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) were incubated in the presence or absence of drugs for specified periods of time. Cells were counted using Trypan blue staining and a hematocytometer. Cells were then spun down and the media was collected. The cells were washed in PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (0.15M NaCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton (v/v) X-100, 0.05 M Tris HCl) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein content was determined using the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Human lambda, kappa, or IgG ELISA kits (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) were used to quantify secreted and intracellular lambda light chain levels. Data were normalized for cell count (secreted) or total protein content (intracellular) and expressed as a percentage of control (untreated cells).

2.5 Immunoblotting

Following incubation with drugs, cells were collected, washed with PBS, and lysed in RIPA buffer as described above. Protein content was determined using the bicinchoninic acid method. Equivalent amounts of cell lysate were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, probed with the appropriate primary antibodies, and detected using HRP-linked secondary antibodies and Amersham Pharmacia Biotech ECL Western blotting reagents. For Ras, Rap1a, Rab6, β-tubulin, GRP78, calnexin, CHOP, and PARP, the membranes were probed with primary antibody for 1 hour at 37 °C. For eIF2α and phospho-eIF2α, membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software.

2.6 [35S]-methionine labeling

Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of drugs (lovastatin, ZA, and DGBP) for 24 hours. Cells were then washed and then incubated in methionine- and cystine-free RPMI medium in the presence or absence of drugs for one hour. A pulse with [35S]-methionine was performed for three hours. At the conclusion of the pulse period, a portion of cells from each condition were lysed and extracted for total protein. The remainder of the cells were washed with complete RPMI medium plus 10 mM methionine and 3 mM cysteine and then incubated for an additional 4–24 hours in the presence or absence of drugs. For immunoprecipitation of lambda light chain, 200 ug of whole cell lysate was incubated with primary antibody for one hour at 4 °C. Protein A/G PLUS-agarose was added and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The pellets were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and dried gels were exposed to film at −80 °C for 7 days. Scintillation counting was used to determine the radioactivity of aliquots of whole cell lysate.

2.7 Real-time PCR

RPMI-8226 cells were grown in the presence or absence of drugs for 24 hours. Each condition was performed in triplicate. RNA was isolated using a RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and a BioRad cDNA synthesis kit was used to prepare cDNA. Lambda light chain primers (forward: ACCCAGCAGTGACATTGGTGACTA, reverse: GTGGCGCTGCCTCTATATGAACT) were designed using PrimerQuest and the coding sequence of the Vλ region of RPMI-8226 [22]. An Applied Biosystems reaction kit with SYBR green was used for the real-time PCR and performed on an Applied Biosystems Model 7900HT. Data was analyzed using ABI SDS 2.3 software and normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA. Quantities were determined using the relative standard curve method. Each sample was run in triplicate.

2.8 Immunofluorescence microscopy studies

RPMI-8226 cells were grown on poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips. Cells were incubated for 24 hours in the absence or presence of drugs. The coverslips were then washed with PBS and cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X 100. Following blocking (4% goat serum, PBS), the coverslips were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 hour, washed with PBS, and then incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor® 568 goat anti-mouse IgG for lambda light chain and Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG for PDI) for 1 hour. The coverslips were again washed with PBS, dried, and mounted in Vecta-Shield with DAPI. Microscopy was performed using a Bio-Rad Radience 2100MP Multiphoton/Confocal microscope with a 60× objective at the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Research Facilities. Images were processed using ImageJ software.

2.9 Statistics

Two-tailed t-testing was used to calculate statistical significance. An α of 0.05 was set as the level of significance.

3. Results

3.1 Inhibition of the IBP alters light chain secretion

As shown in Figure 1A, lovastatin, ZA, and DGBP specifically inhibit enzymes in the IBP. To determine whether inhibition of this pathway results in disruption of light chain secretion, RPMI-8226 cells were incubated with varying concentrations of lovastatin, ZA, or DGBP for 24 hours. As shown in Figure 1B, incubation with lovastatin results in an increase in intracellular lambda light chain levels as well as a decrease in secreted light chain. Both ZA and DGBP also increase intracellular lambda light chain levels. While ZA has modest effects on secreted light chain, DGBP induces a concentration-dependent decrease in secreted protein. Incubation with zaragozic acid, a squalene synthase (SQS) inhibitor which inhibits sterol synthesis and leads to an increase in FPP and GGPP levels [23,24], did not alter light chain levels (data not shown). Lovastatin, but not ZA or DGBP, disrupted light chain secretion and induced an accumulation of intracellular light chain in U266 cells (Figure 1C). We have previously shown that the U266 cell line is relatively resistant to the inhibition of protein prenylation by ZA or DGBP as a consequence of elevated basal FPP and GGPP levels [10]. Therefore, these results suggest that the ability of the IBP inhibitors to alter light chain levels in these cell lines is dependent on their ability to alter isoprenoid levels.

To determine whether the effects of these drugs are a consequence of depletion of a specific isoprenoid species, experiments were performed in which cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the drugs and mevalonate, FPP, or GGPP. Lovastatin, as an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, depletes cells of all down-stream products, including mevalonate, FPP, and GGPP. Although ZA is an FDPS inhibitor, we have previously demonstrated that while ZA does decrease GGPP levels, it paradoxically increases FPP levels in RPMI-8226 cells [10]. Finally, DGBP selectively inhibits GGDPS and therefore only depletes cells of GGPP [10]. As shown in figure 1D, co-incubation of lovastatin with mevalonate or GGPP, but not FPP, completely prevents the effects of lovastatin on intracellular light chain levels. GGPP synthesis requires both FPP and IPP, therefore addition of FPP does not restore GGPP synthesis in the setting of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition. Only GGPP prevents the accumulation of intracellular light chain induced by ZA and DGBP. The ability of specific isoprenoids to prevent the induced effects of the pathway inhibitors correlates with their effects on protein prenylation. Mevalonate and GGPP, but not FPP, prevents lovastatin-induced inhibition of Rap1a and Rab6 geranylgeranylation (Supplemental Figure 1). However, only GGPP prevents ZA- and DGBP-induced inhibition of geranylgeranylation (Supplemental Figure 1). These results suggest that depletion of GGPP with subsequent inhibition of geranylgeranylation is responsible for the observed effects on light chain secretion.

3.2 Inhibition of Rab geranylgeranylation disrupts light chain trafficking

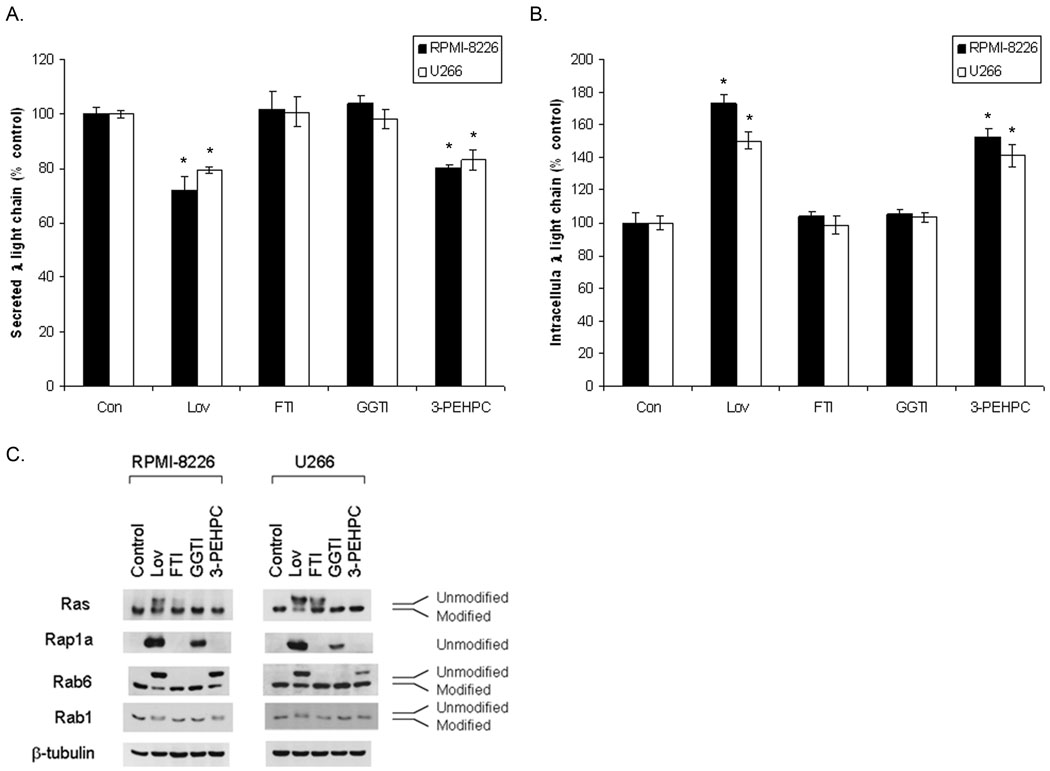

Depletion of GGPP, via agents which inhibit the IBP, interferes with the geranylgeranylation of substrates for both GGTase I (e.g., Rap1a) and GGTase II (Rabs) (Figure 1A). To more directly determine the effects of inhibition of prenylation on light chain trafficking, experiments were performed in which RPMI-8226 and U266 cells were incubated with specific inhibitors of FTase (FTI-277), GGTase I (GGTI-2133) or GGTase II (3-PEHPC). As shown in figure 2A–B, 3-PEHPC, but not FTI-277 or GGTI-2133 results in a decrease in secreted light chain and an accumulation of intracellular light chain in RPMI-8226 and U266 cells. Interestingly, higher concentrations of the GGTase I inhibitor decreased intracellular light chain levels by approximately 20% in both cell lines (data not shown). Other GGTase I inhibitors (GGTI-298 and GGTI-286), yielded similar results in the U266 line (data not shown). Incubation of cells with Y-27632, a Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, did not significantly alter light chain levels (data not shown). Specificity of the inhibitors with respect to the GGTase enzymes in these cell lines was confirmed (Figure 2C). The GGTase II inhibitor, 3-PEHPC, inhibits only Rab geranylgeranylation, as demonstrated by the appearance of the more slowly migrating Rab6 and Rab1 bands but has no effect on Rap1a geranylgeranylation. Consistent with GGTase I inhibition, GGTI-2133 inhibits Rap1a geranylgeranylation but not Rab6 or Rab1 geranylgeranylation. In addition, 3-PEHPC does not inhibit Ras farnesylation in either cell line. Figure 2C demonstrates that the RPMI-8226 cells are more sensitive to 3-PEHPC with respect to inhibition of Rab geranylgeranylation while the U266 cells are more sensitive to GGTI-2133 with respect to inhibition of Rap1a geranylgeranylation.

Figure 2. Effects of prenyltransferase inhibitors on intracellular light chain levels in human myeloma cells.

RPMI-8226 and U266 cells were cultured with 20 uM Lov, 10 uM FTI-277, 10 uM GGTI-2133, or 5 mM 3-PEHPC for 24 hours. Secreted (A) and intracellular (B) lambda light chain levels were measured via ELISA. Data are expressed as a percentage of control (mean ± SD, n=3). The * denotes p<0.05 per unpaired two-tailed t-test. C). Immunoblot analysis of Ras, Rab6, Rab1 (modified and unmodified) and Rap1a (unmodified). β-Tubulin is shown as a loading control.

Select IBP inhibitors and 3-PEHPC also induce increases in intracellular monoclonal protein levels in primary myeloma cells. As shown in Table 1, more pronounced effects were observed at 48 hours compared with 24 hours, although lovastatin induced a statistically significant increase in intracellular monoclonal protein levels in all patient samples. In aggregate, these studies provide evidence that inhibition of Rab geranylgeranylation, either via direct inhibition of GGTase II, or through depletion of GGPP, is responsible for disruption of light chain trafficking.

Table 1. Effects of IBP inhibitors on intracellular monoclonal protein levels in primary myeloma cells.

Primary plasma cells isolated from bone marrow aspirate (patients 1–3) or peripheral blood (patient 4) were incubated with IBP inhibitors and intracellular monoclonal protein levels were determined via ELISA as described in the Material and Methods section.

| Patient | Measured monoclonal protein |

Incubation time (h) |

Treatment | Intracellular protein (% control ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kappa | 24 | Con | 100.0 ± 1.2 |

| 20 uM Lov | 121.8 ± 7.5* | |||

| 50 uM ZA | 99.0 ± 5.1 | |||

| 20 uM DGBP | 97.5 ± 4.6 | |||

| 2 | Kappa | 48 | Con | 100.0 ± 3.8 |

| 50 uM Lov | 202.4 ± 14.6* | |||

| 50 uM DGBP | 264.1 ± 11.9* | |||

| 5 mM 3-PEHPC | 186.5 ± 7.8* | |||

| 3 | IgG | 48 | Con | 100.0 ± 3.9 |

| 50 uM Lov | 129.8 ± 4.8* | |||

| 50 uM DGBP | 136.2 ± 6.7* | |||

| 5 mM 3-PEHPC | 133.6 ± 3.3* | |||

| 4** | IgG | 48 | Con | 100.0 ± 3.6 |

| 10 uM Lov | 151.9 ± 2.3* | |||

| 50 uM ZA | 92.4 ± 8.0 | |||

| 10 uM DGBP | 145.2 ± 11.9* | |||

| 10 uM GGTI-2133 | 109.9 ± 9.8 | |||

| 5 mM 3-PEHPC | 215.3 ± 9.8* | |||

denotes p<0.05 per unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Patient 4: IgG plasma cell leukemia

3.3 IBP inhibition induces intracellular accumulation of newly synthesized light chain

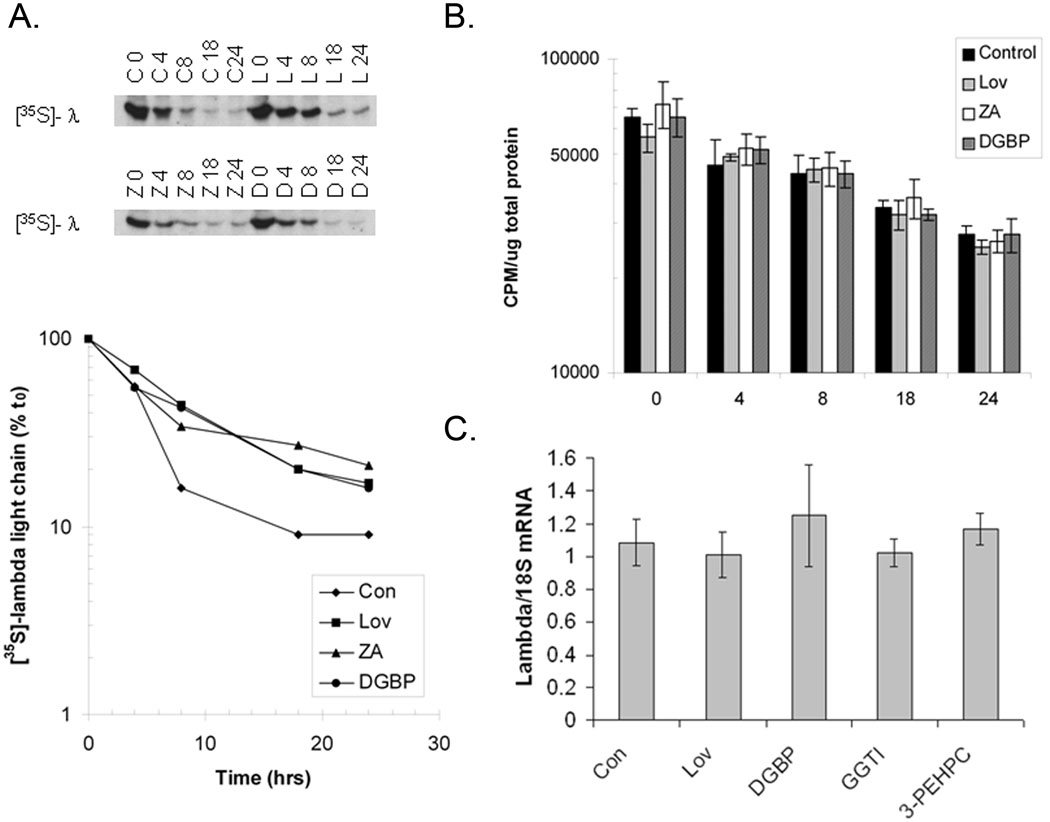

In order to determine the effects of IBP inhibition on newly synthesized lambda light chain protein, pulse-chase experiments were performed in which RPMI-8226 cells treated with IBP inhibitors were labelled with [35S]-methionine. Under control conditions (Figure 3A), the majority of newly synthesized lambda light chain is secreted within 8 hours. In contrast, treatment with lovastatin, ZA, or DGBP results in persistence of labelled protein within the cells. Treatment with the IBP inhibitors did not alter loss of the radiolabel from total protein pools over time, compared with control (Figure 3B). These studies demonstrate persistence of newly synthesized light chain within the cells following treatment with IBP inhibitors. To determine whether inhibition of geranylgeranylation alters transcription of lambda light chain, real-time PCR experiments were performed. As shown in figure 3C, treatment with lovastatin, DGBP, GGTI-2133, or 3-PEHPC did not significantly alter lambda light chain mRNA levels.

Figure 3. IBP inhibitors induce an intracellular accumulation of newly synthesized light chain without altering light chain mRNA.

RPMI-8226 cells incubated with 20 uM lovastatin (L), 50 uM ZA (Z), 20 uM DGBP (D) or without drugs (control, C) were labeled with [35S]-methionine as described in the Methods section. A) Radiolabeled lambda light chain and densitometric analysis with relative intensities expressed as a percentage of the intensity at the conclusion of the pulse period (t0) for each condition. B). Changes in [35S]-methionine-labelled protein in whole cell lysate over time were determined via liquid scintillation counting. Data are expressed as amount of radioactivity per ug total protein (mean ± SD, n=3). C). RPMI-8226 cells were incubated with 10 uM Lov, 10 uM DGBP, 10 uM GGTI-2133 (GGTI), or 5 mM 3-PEHPC for 24 hours. Real-time PCR was performed using primers for lambda light chain and 18S ribosomal RNA. Data are expressed as amount of lambda light chain mRNA relative to 18S (mean ± SD, n=3).

3.4 Inhibition of the IBP results in accumulation of light chain in the endoplasmic reticulum

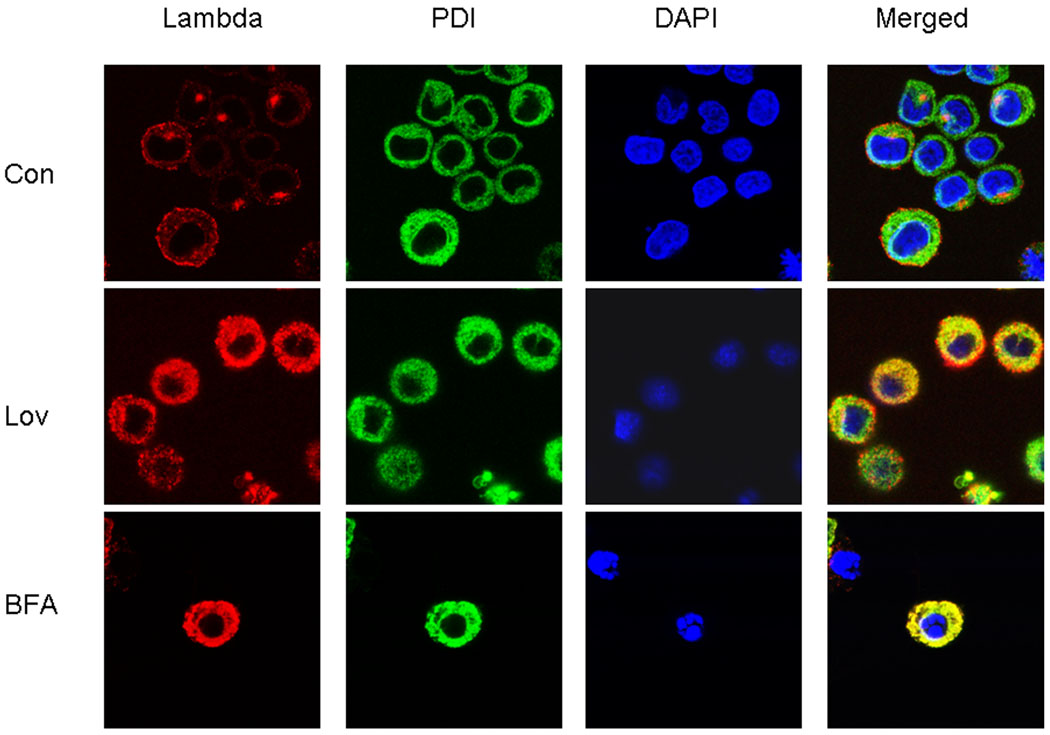

The ELISA and pulse-chase experiments demonstrated that IBP inhibition results in intracellular accumulation of light chain. To better define the effects of IBP inhibition on the localization of light chain, immunofluorescence microscopy studies were performed. Brefeldin A, a known inhibitor of ER to Golgi transport, was used as a positive control [25]. Cells were stained with primary antibodies directed against lambda light chain and the ER resident protein disulfide isomerase (PDI). Nuclear staining was achieved with DAPI. Under control conditions, lambda light chain staining consists of a diffuse vesicular-like pattern throughout the cytoplasm as well as a more intense peri-nuclear staining (Figure 4). Consistent with the presence of marked expansion of ER in plasma cells, staining with PDI demonstrates that the cytoplasm is composed predominantly of ER. Merging reveals that under control conditions there is little co-localization between lambda light chain and PDI, suggesting rapid trafficking through the ER and with primary localization in secretory vesicles and Golgi. In contrast, there is intense lambda light chain staining throughout the cytoplasm in lovastatin- or brefeldin A-treated cells. There is marked co-localization of lambda light chain and PDI in these cells, as demonstrated in the merged images. Similar results were observed in cells treated with DGBP (data not shown). Lovastatin does not alter PDI levels, as determined by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). These studies provide evidence that inhibition of the IBP leads to accumulation of light chain in the endoplasmic reticulum.

Figure 4. Inhibition of the IBP results in accumulation of light chain in the endoplasmic reticulum.

RPMI-8226 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 10 uM lovastatin or 2 uM brefeldin A for 24 hours. Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described in the Methods section using antibodies directed against lambda light chain and PDI. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. The merged images represent merging of the lambda, PDI, and DAPI images via ImageJ software.

3.5 IBP inhibition activates the unfolded protein response and induces apoptosis

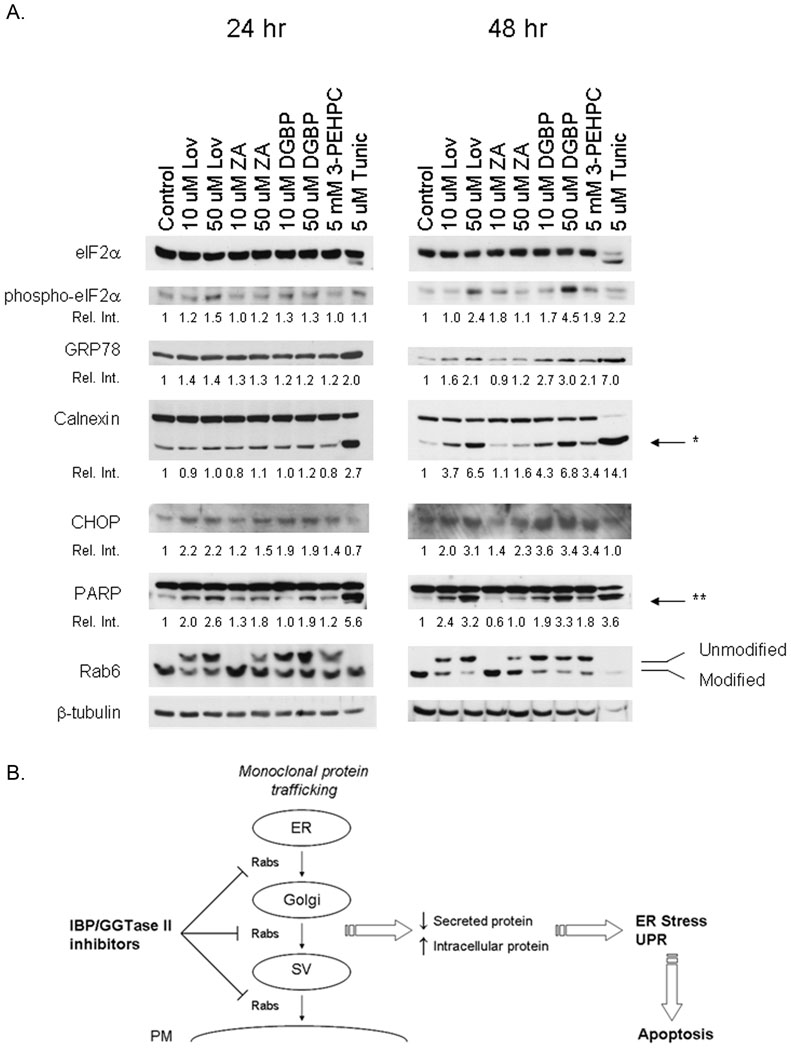

Accumulation of protein within the ER can induce a stress signaling pathway referred to as the UPR. This response invokes several protective measures, including a decrease in protein synthesis and an increase in ER chaperone proteins and folding enzymes [2]. If left unchecked, the UPR can lead to induction of apoptosis [2]. To determine whether the accumulation of light chain induced by inhibition of the IBP results in activation of the UPR, immunoblot studies were performed. RPMI-8226 cells were incubated with drugs for 24 or 48 hours. Tunicamycin, a known inducer of ER stress and the UPR, was used as a positive control. Transduction of the UPR leads to phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) which results in a global decrease in translation initiation [2]. As shown in Figure 5A, lovastatin, and to a lesser extent DGBP, induces an increase in phosphorylated eIF2α at 24 hours. This effect is enhanced at 48 hours and is also observed with 3-PEHPC. At 24 hours there is not a significant effect on GRP78, an ER molecular chaperone. However, at 48 hours lovastatin, DGBP, and 3-PEHPC induce a greater than two-fold increase in GRP78 levels. Although levels of calnexin, another ER molecular chaperone, do not change, there is an increase in calnexin cleavage which is most evident at 48 hours. Concentration-dependent effects were observed with lovastatin, ZA, and DGBP. Calnexin cleavage has been previously demonstrated to occur in response to apoptotic stimuli, including ER stress [26]. To more directly examine the effects of these agents on ER stress/UPR-mediated apoptosis, CHOP levels were measured. CHOP is one of the key mediators of ER stress- and UPR-induced apoptosis and is induced via both the PERK and ATF6 UPR pathways [27,28]. The IBP inhibitors and 3-PEHPC increase CHOP levels by more than three-fold at 48 hours. That tunicamycin-induced CHOP expression is not observed at 24 and 48 hours is consistent with previous findings showing that this agent has maximal effects at 12 hours in this cell line [4]. Finally, to confirm induction of apoptosis, PARP cleavage was measured. Induction of PARP cleavage was observed with all tested agents. The relative effects of these agents on phospho-eIF2α, GRP78, calnexin, CHOP, and PARP correlate with the degree of inhibition of Rab geranylgeranylation. Both lovastatin and 3-PEHPC induced phosphorylation of eIF2α, upregulated CHOP, and induced PARP cleavage in the U266 cells at 48 hours (supplemental figure 2). In conclusion, these studies demonstrate that agents which effectively inhibit Rab geranylgeranylation induce the UPR. In aggregate, this work is consistent with the following model (Figure 5B): select inhibitors of the IBP induce apoptosis in myeloma cells via their ability to inhibit Rab geranylgeranylation, leading to disruption of monoclonal protein trafficking and induction of the UPR pathway.

Figure 5. Effects of IBP inhibition on UPR activation and induction of apoptosis.

A). RPMI-8226 cells were cultured with varying concentrations of Lov, ZA, DGBP, 3-PEHPC or tunicamycin (Tunic) for 24 or 48 hours. Immunoblot analysis was performed for total eIF2α, phosphorylated eIF2α (phospho-eIF2α), GRP78, calnexin, CHOP, PARP, Rab6, and β-tubulin (as a loading control). The relative intensity (Rel. Int.) was determined using densitometry and compares the treated cells versus the control cells. For calnexin and PARP the relative intensity refers to the cleavage products. * Denotes the calnexin cleavage product while ** denotes the PARP cleavage product. These gels are representative of three independent experiments. B) Proposed model by which IBP inhibition disrupts monoclonal protein trafficking and induces apoptosis in myeloma cells. Abbreviations: IBP, isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway; SV, secretory vesicle; PM, plasma membrane; UPR, unfolded protein response.

4. Discussion

In the studies presented here we have demonstrated that inhibition of the IBP disrupts secretion with concomitant intracellular accumulation of monoclonal protein in human myeloma cells. Utilization of specific inhibitors of each step in the pathway, in combination with add-back experiments, revealed that depletion of GGPP was responsible for the effects on light chain secretion (Figure 1). That the effects of ZA and DGBP on the U266 cell line were substantially less than in the RPMI-8226 cell line is consistent with our previous findings which revealed that the U266 cells have high basal isoprenoid levels and as such are relatively resistant to depletion of these isoprenoids and disruption of protein prenylation [10]. Interestingly, the primary myeloma cells displayed differential sensitivity to the IBP inhibitors with respect to induced changes in intracellular monoclonal protein levels (Table 1). Whether this finding is due to differences in basal isoprenoid levels amongst patient samples is an intriguing possibility that remains to be determined.

GGPP is utilized as a substrate for geranylgeranylation reactions and as a precursor for ubiquinone and retinoid synthesis. In addition, GGPP itself has been shown to have regulatory properties [29]. In order to determine whether the effects induced by depletion of GGPP are due to loss of geranylgeranylation vs. depletion of a GGPP-derived product, experiments were performed utilizing specific prenyltransferase inhibitors (Figure 2). These studies confirmed that inhibition of GGTase II, but not FTase or GGTase I, induces an accumulation of light chain similar to that observed with agents that deplete cells of GGPP. As the only known substrates of GGTase II are the Rab proteins, these studies provide evidence that it is disruption of Rab geranylgeranylation, either through direct inhibition of GGTase II or through depletion of GGPP, which leads to the perturbation in light chain trafficking. Although 3-PEHPC lacks potency (mM concentrations are required to induce cellular effects), it has been shown to be highly specific for GGTase II [21]. That this drug could be having effects on other cellular processes remains a possibility, thus the development of more potent GGTase II inhibitors will be of critical importance in further defining the role of Rab proteins in myeloma cells.

Labeling of newly synthesized protein with [35S]-methionine revealed that IBP inhibition leads to a persistence of intracellular radiolabeled lambda light chain (Figure 3). This effect could be due to either a decrease in secretion or a decrease in light chain degradation. Although there have been reports that select statins, including lovastatin, can alter proteasome activity, these effects were specific to the pro-drug closed ring form and not to the dihydroxy opened ring form [30]. Analysis of total protein pools revealed that the IBP inhibitors did not affect the rate of global loss of radiolabel over time or alter light chain mRNA levels (Figure 3). These results, in conjunction with the observed accumulation of light chain in the endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 4) are consistent with inhibition of the secretory pathway.

As has been demonstrated with other prenylated proteins, proper cellular localization of Rab proteins is dependent on geranylgeranylation. Gomes et al. have demonstrated that mutant forms of Rabs that are unable to be digeranylgeranylated are mistargeted and nonfunctional [16]. In addition, 3-PEHPC has been shown to induce the cytosolic accumulation of unmodified Rab proteins [31]. 3-PEHPC and the IBP inhibitors globally disrupt Rab geranylgeranylation. Distinct Rab proteins are involved with each step in the secretory pathway. The immunofluorescence studies (Figure 4) demonstrate that the majority of the light chain appears to be located in the endoplasmic reticulum in cells treated with lovastatin, suggesting that ER to Golgi transport is disrupted. However, it is likely that Golgi to secretory vesicle and secretory vesicle to cytoplasmic membrane trafficking are also perturbed in this setting. Further studies will be warranted to define the role of individual Rab proteins in mediating monoclonal protein trafficking and to determine whether selective vs. global inhibition of Rab function yields the more pronounced effects.

Production of vast quantities of monoclonal protein is the hallmark of multiple myeloma. Plasma cells, both benign and malignant, require the cellular components necessary to achieve this protein production including a marked expansion of endoplasmic reticulum. Obeng et al. have demonstrated that myeloma cells constitutively express high levels of UPR components [4]. These studies provided an explanation for the enhanced sensitivity of myeloma cells to proteasome inhibitors. Proteasome inhibitors lead to an accumulation of intracellular light chain which in turn activates the pro-apoptotic aspect of the UPR [4]. Our studies demonstrate that agents which inhibit Rab geranylgeranylation, either directly or indirectly, activate both the protective (phosphorylation of eIF2α and induction of GRP78) and pro-apoptotic (upregulation of CHOP, cleavage of calnexin and PARP) aspects of the UPR (figure 5A). That these effects are more pronounced at 48 hours than at 24 hours is consistent with the need for clearance of existing prenylated Rab proteins as well as the synthesis and cytosolic accumulation of unmodified Rab proteins. The half-life of Ras and Ras-related proteins has been shown to be approximately 24 hours [32,33]. Importantly, complete cessation of protein secretion is not needed to induce these effects; observed changes in intracellular levels range from 40 to 80% while observed changes in secreted protein range from 20 to 40%. From a therapeutic standpoint, complete inhibition of protein secretion would have unacceptable toxicity. However, an approach which partially disrupts protein trafficking would be predicted to have a much greater impact on cells highly dependent on protein secretion (i.e., myeloma cells) compared with nonsecretory cells, thereby providing specificity and a therapeutic index. It is intriguing to hypothesize that this approach may be of particular importance in the setting of amyloid light chain disease, given the inherent toxicity of amyloid fibrils.

The predominant role for aminobisphosphonates such as pamidronate and zoledronic acid in myeloma has been to combat myeloma bony disease. These agents have been shown to have potent effects on osteoclasts and the bisphosphonate moiety allows for effective targeting to bone [34]. While there is evidence that these agents can induce myeloma plasma cell death in vitro [6,10,35] there is less evidence to suggest that they provide significant effects on overall myeloma disease burden. That the GGTase II inhibitor 3-PEHPC (which is an analogue of the aminobisphosphonate risedronate) has been demonstrated to reduce osteolytic bone lesions in a mouse model of myeloma [36] suggests that this agent is also capable of targeting bone and inducing cytotoxic effects in osteoclasts. Our results suggest that GGTase II may be a key target in myeloma plasma cells. Further development of more potent GGTase II inhibitors which possess a lower affinity for bone and thus have a higher bioavailability for myeloma plasma cells could lead to novel therapeutic agents.

The effects of IBP inhibitors on light chain trafficking and the UPR suggests the potential for enhanced cytotoxicity when combined with other agents which target malignant plasma cells. Interestingly, in a very small pilot phase II trial involving myeloma patients refractory to bortezomib or bendamustine, the addition of simvastatin yielded a decrease in serum paraprotein levels [37]. In addition, simvastatin was able to induce apoptosis in a cell line characterized by increased proteasome activity and resistance to bortezomib [38]. Given the fact that aminobisphosphonates are extensively used to treat myeloma bony disease and that statins comprise one of the most commonly prescribed classes of drugs in the United States, there is a wealth of opportunity for the study of these drugs in combination with bortezomib and other agents in myeloma, both retrospectively and prospectively.

In conclusion, these studies are the first to reveal that IBP inhibition, and more specifically, inhibition of Rab geranylgeranylation, results in disruption of monoclonal protein trafficking in multiple myeloma cells. Furthermore, the resulting accumulation of intracellular monoclonal protein activates the UPR and induces apoptosis. These findings provide a novel mechanism of action for inhibitors of the IBP in multiple myeloma. Targeting the trafficking and secretion of monoclonal protein represents a novel approach in myeloma and, by virtue of resulting effects on ER stress and the UPR, is an approach which has the potential to selectively induce myeloma cell death. These data provide rationale for the further development of Rab-targeted agents in myeloma and for exploration of the effects of combination of IBP inhibitors with existing therapeutic agents.

Supplementary Material

RPMI-8226 cells were incubated with 10 µM lovastatin (Lov), 50 µM ZA, or 10 µM DGBP in the presence or absence of 1 mM mevalonate (Mev), 10 µM FPP, or 10 µM GGPP for 24 hours. Immunoblot analysis of Rap1a and Rab6 in RPMI-8226 cells cultured as described in Figure 1D. β-Tubulin is shown as a loading control.

U266 cells were incubated in the presence of absence of 50 uM lovastatin (Lov) or 10 mM 3-PEHPC for 48 hours. Immunoblot analysis was performed for total eIF2α, phosphorylated eIF2α (phospho-eIF2α), CHOP, PARP, Rab6, and β-tubulin (as a loading control). The relative intensity (Rel. Int.) was determined using densitometry and compares the treated cells versus the control cells. *Denotes the PARP cleavage product.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Kathy Walters from the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Facility for her assistance with the microscopy studies. We also wish to thank Rocky Barney from the Department of Chemistry at the University of Iowa for the synthesis of 3-PEHPC. This project was supported by the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust as a Research Program of Excellence and the Roland W. Holden Family Program for Experimental Cancer Therapeutics. S.A.H. was supported through a NIH T32 training grant [T32 HL07734].

Nonstandard abbreviations

- DGBP

digeranyl bisphosphonate

- DMAPP

dimethyl allyl diphosphate

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FDPS

farnesyl diphosphate synthase

- FPP

farnesyl diphosphate

- FTase

farnesyl transferase

- GGDPS

geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase

- GGPP

geranylgeranyl diphosphate

- GGTase

geranylgeranyl transferase

- GPP

geranyl diphosphate

- HMG-CoA

hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A

- IBP

isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway

- IPP

isopentenyl diphosphate

- Lov

lovastatin

- SQS

squalene synthase

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- ZA

zoledronic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author’s Contributions

SAH and RJH provided the conception and design, acquisition of data, or interpretation of data, dafting the article and final approval.

Conflict of Interest

S.A.H. has no conflicts of interest. R.J.H is a founder of and has an equity position in Terpenoid Therapeutics, Inc.

References

- 1.Brewer JW, Hendershot LM. Building an antibody factory: a job for the unfolded protein response. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:23–29. doi: 10.1038/ni1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. The endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:716–731. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunn KE, Gifford NM, Mori K, Brewer JW. A role for the unfolded protein response in optimizing antibody secretion. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obeng EA, Carlson LM, Gutman DM, Harrington WJ, Jr, Lee KP, Boise LH. Proteasome inhibitors induce a terminal unfolded protein response in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107:4907–4916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes DE, Wright KR, Uy HL, Sasaki A, Yoneda T, Roodman GD, Mundy GR, Boyce BF. Bisphosphonates promote apoptosis in murine osteoclasts in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1478–1487. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koizumi M, Nakaseko C, Ohwada C, Takeuchi M, Ozawa S, Shimizu N, Cho R, Nishimura M, Saito Y. Zoledronate has an antitumor effect and induces actin rearrangement in dexamethasone-resistant myeloma cells. Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:382–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Beek E, Pieterman E, Cohen L, Lowik C, Papapoulos S. Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase is the molecular target of nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264:108–111. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergstrom JD, Bostedor RG, Masarachia PJ, Reszka AA, Rodan G. Alendronate is a specific, nanomolar inhibitor of farnesyl diphosphate synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;373:231–241. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van de Donk NW, Kamphuis MM, Lokhorst HM, Bloem AC. The cholesterol lowering drug lovastatin induces cell death in myeloma plasma cells. Leukemia. 2002;16:1362–1371. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holstein SA, Tong H, Hohl RJ. Differential activities of thalidomide and isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway inhibitors in multiple myeloma cells. Leuk Res. 2010;34:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochiai N, Uchida R, Fuchida S, Okano A, Okamoto M, Ashihara E, Inaba T, Fujita N, Matsubara H, Shimazaki C. Effect of farnesyl transferase inhibitor R115777 on the growth of fresh and cloned myeloma cells in vitro. Blood. 2003;102:3349–3353. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roelofs AJ, Hulley PA, Meijer A, Ebetino FH, Russell RG, Shipman CM. Selective inhibition of Rab prenylation by a phosphonocarboxylate analogue of risedronate induces apoptosis, but not S-phase arrest, in human myeloma cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1254–1261. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Donk NW, Kamphuis MM, van Kessel B, Lokhorst HM, Bloem AC. Inhibition of protein geranylgeranylation induces apoptosis in myeloma plasma cells by reducing Mcl-1 protein levels. Blood. 2003;102:3354–3362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultz J, Doerks T, Ponting CP, Copley RR, Bork P. More than 1,000 putative new human signalling proteins revealed by EST data mining. Nat Genet. 2000;25:201–204. doi: 10.1038/76069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuda M. Regulation of secretory vesicle traffic by Rab small GTPases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2801–2813. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes AQ, Ali BR, Ramalho JS, Godfrey RF, Barral DC, Hume AN, Seabra MC. Membrane targeting of Rab GTPases is influenced by the prenylation motif. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1882–1899. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vishnuvardhan D, Beinfeld MC. Lovastatin is a potent inhibitor of cholecystokinin secretion in endocrine tumor cells in culture. Peptides. 2000;21:553–557. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostrowski SM, Wilkinson BL, Golde TE, Landreth G. Statins reduce amyloid-beta production through inhibition of protein isoprenylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26832–26844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702640200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau AS, Jia X, Patterson CJ, Roccaro AM, Xu L, Sacco A, O'Connor K, Soumerai J, Ngo HT, Hatjiharissi E, et al. The HMG-CoA inhibitor, simvastatin, triggers in vitro anti-tumour effect and decreases IgM secretion in Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:775–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shull LW, Wiemer AJ, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Synthesis and biological activity of isoprenoid bisphosphonates. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:4130–4136. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coxon FP, Helfrich MH, Larijani B, Muzylak M, Dunford JE, Marshall D, McKinnon AD, Nesbitt SA, Horton MA, Seabra MC, et al. Identification of a novel phosphonocarboxylate inhibitor of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase that specifically prevents Rab prenylation in osteoclasts and macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48213–48222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohno S, Yoshimoto M, Honda S, Miyachi S, Ishida T, Itoh F, Endo T, Chiba S, Imai K. The antisense approach in amyloid light chain amyloidosis: identification of monoclonal Ig and inhibition of its production by antisense oligonucleotides in in vitro and in vivo models. J Immunol. 2002;169:4039–4045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergstrom JD, Kurtz MM, Rew DJ, Amend AM, Karkas JD, Bostedor RG, Bansal VS, Dufresne C, VanMiddlesworth FL, Hensens OD, et al. Zaragozic acids: a family of fungal metabolites that are picomolar competitive inhibitors of squalene synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:80–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong H, Holstein SA, Hohl RJ. Simultaneous determination of farnesyl and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate levels in cultured cells. Anal Biochem. 2005;336:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misumi Y, Miki K, Takatsuki A, Tamura G, Ikehara Y. Novel blockade by brefeldin A of intracellular transport of secretory proteins in cultured rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11398–11403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takizawa T, Tatematsu C, Watanabe K, Kato K, Nakanishi Y. Cleavage of calnexin caused by apoptotic stimuli: implication for the regulation of apoptosis. J Biochem. 2004;136:399–405. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ron D, Habener JF. CHOP, a novel developmentally regulated nuclear protein that dimerizes with transcription factors C/EBP and LAP and functions as a dominant-negative inhibitor of gene transcription. Genes Dev. 1992;6:439–453. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Y, Brewer JW, Diehl JA, Hendershot LM. Two distinct stress signaling pathways converge upon the CHOP promoter during the mammalian unfolded protein response. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:1351–1365. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holstein SA, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Hohl RJ. Isoprenoids influence expression of Ras and Ras-related proteins. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13698–13704. doi: 10.1021/bi026251x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao S, Porter DC, Chen X, Herliczek T, Lowe M, Keyomarsi K. Lovastatin-mediated G1 arrest is through inhibition of the proteasome, independent of hydroxymethyl glutaryl-CoA reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coxon FP, Ebetino FH, Mules EH, Seabra MC, McKenna CE, Rogers MJ. Phosphonocarboxylate inhibitors of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase disrupt the prenylation and membrane localization of Rab proteins in osteoclasts in vitro and in vivo. Bone. 2005;37:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holstein SA, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Hohl RJ. Consequences of mevalonate depletion. Differential transcriptional, translational, and post-translational up-regulation of Ras, Rap1a, RhoA, AND RhoB. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10678–10682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramalho JS, Anders R, Jaissle GB, Seeliger MW, Huxley C, Seabra MC. Rapid degradation of dominant-negative Rab27 proteins in vivo precludes their use in transgenic mouse models. BMC Cell Biol. 2002;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimmel DB. Mechanism of action, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile, and clinical applications of nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. J Dent Res. 2007;86:1022–1033. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shipman CM, Croucher PI, Russell RG, Helfrich MH, Rogers MJ. The bisphosphonate incadronate (YM175) causes apoptosis of human myeloma cells in vitro by inhibiting the mevalonate pathway. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5294–5297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawson MA, Coulton L, Ebetino FH, Vanderkerken K, Croucher PI. Geranylgeranyl transferase type II inhibition prevents myeloma bone disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:453–457. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidmaier R, Baumann P, Bumeder I, Meinhardt G, Straka C, Emmerich B. First clinical experience with simvastatin to overcome drug resistance in refractory multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:240–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuchs D, Berges C, Opelz G, Daniel V, Naujokat C. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin overcomes bortezomib-induced apoptosis resistance by disrupting a geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate-dependent survival pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

RPMI-8226 cells were incubated with 10 µM lovastatin (Lov), 50 µM ZA, or 10 µM DGBP in the presence or absence of 1 mM mevalonate (Mev), 10 µM FPP, or 10 µM GGPP for 24 hours. Immunoblot analysis of Rap1a and Rab6 in RPMI-8226 cells cultured as described in Figure 1D. β-Tubulin is shown as a loading control.

U266 cells were incubated in the presence of absence of 50 uM lovastatin (Lov) or 10 mM 3-PEHPC for 48 hours. Immunoblot analysis was performed for total eIF2α, phosphorylated eIF2α (phospho-eIF2α), CHOP, PARP, Rab6, and β-tubulin (as a loading control). The relative intensity (Rel. Int.) was determined using densitometry and compares the treated cells versus the control cells. *Denotes the PARP cleavage product.