Although the most commonly identified causes of acute liver failure (ALF) are drug toxicities and viral hepatitis, neoplastic infiltration of the liver can also cause ALF. This case report describes acute hepatic decompensation from an occult breast malignancy that was diagnosed antemortem and discusses 2 previously reported cases of this condition in which the diagnosis was made postmortem.

Case Report

A 38-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presented to our hospital with a 2-week history of malaise, lethargy, sore throat, and dyspnea. A physical examination revealed normal vital signs and mild pharyngeal erythema. The patient's laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 13,500 cells/mm3, with 37% neutrophils, 41% lymphocytes, 8% bands, 2% myelocytes, and 3% metamyelocytes. Her hemoglobin level was 14.4 g/dL, and her platelet count was 123,000 cells/mm3. A peripheral blood smear revealed thrombocytopenia, normal red blood cell morphology, and 4% atypical lymphocytes. Liver function tests (LFTs) revealed a total bilirubin (TB) level of 1.3 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 235 IU/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) of 450 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 491 IU/L, international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.7, and amylase of 104 IU/L. The patient's D-dimer and C-reactive protein levels were increased to 18.16 μg/mL and 34.0 mg/L, respectively. An electrocardiogram and chest radiograph were unremarkable. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed ground glass opacities and small juxtapleural nodules bilaterally in the lower lobes, a small pericardial and left pleural effusion, a small amount of perihepatic ascites, and a heterogeneous-appearing liver.

The patient was admitted for possible viral syndrome or atypical bacterial pneumonia. Treatment with empiric moxifloxacin was started. Negative test results were found for Epstein-Barr virus capsid immunoglobulin (Ig)M antibody, cytomegalovirus IgM antibody, Group A Streptococcus rapid antigen, nasopharyngeal influenza antigen, Legionella urine antigen, Chlamydia and Mycoplasma serologies, and blood and oropharyngeal cultures. Additionally, negative results were found for antinuclear antibody; antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody; anti– double-stranded DNA; acute and chronic hepatitis A, B, and C serologies; antimitochondrial antibody; antismooth muscle antibody; and alpha-1 antitrypsin. A transthoracic echocardiogram was unremarkable.

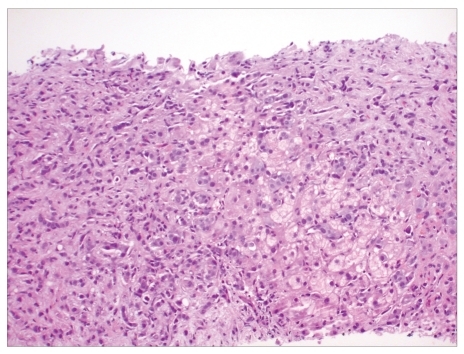

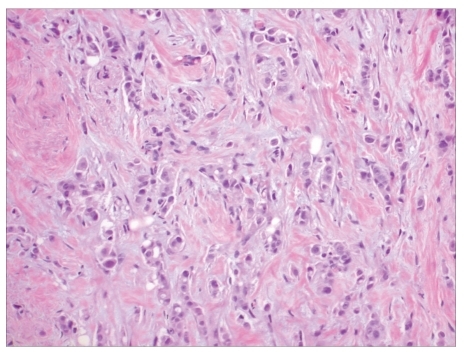

The patient was treated conservatively and discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of viral syndrome. However, she returned 2 weeks later with complaints of progressive fatigue, abdominal discomfort, and new abdominal distension. Physical examination findings included hepatomegaly and shifting dullness suggestive of ascites. Her LFTs revealed a TB level of 2.2 mg/dL, direct bilirubin of 1.22 mg/dL, ALP of 255 IU/L, AST of 876 IU/L, ALT of 496 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase of 361 IU/L, and INR of 2.1. The patient's lactate dehydrogenase measured 1,138 IU/L, and her complete blood cell count showed a hemoglobin level of 8.6 g/dL and platelet count of 35,000 cells/mm3. Her serum acetaminophen level was undetectable. A repeat CT scan revealed an enlarged heterogeneous liver; periportal adenopathy; an increase in pericardial, pleural, and peritoneal fluids; disseminated lytic vertebral body lesions; left axillary adenopathy; and the development of right-sided hydronephrosis. A transjugular liver biopsy revealed severe acute hepatitis with necrosis, evolving fibrosis, and many monomorphic atypical cells staining positive for CAM 5.2, AE1/3, Her-2/neu (score 3), mammaglobin, GCDFP-15, and CK 7, which are suggestive of primary breast carcinoma metastases (Figure 1). A liver biopsy also revealed elevated indirect portal pressure with an elevated portosystemic gradient of 19 mmHg (normal range, 8–12 mmHg). A mammogram showed a suspicious calcification in the left breast, and an ultrasound of the breast showed a retro areolar mass measuring 1.3 cm × 0.9 cm × 1.1 cm and left axillary adenopathy. A core biopsy of the left retroareolar lesion revealed invasive ductal carcinoma (nuclear grade 2) with lymphovascular invasion (Figure 2). An immunohistochemical stain was negative for estrogen receptor protein, positive for progesterone receptor protein (60%), and positive (3+) for HER-2/neu. Cytologic analysis of ascitic fluid and bone marrow aspirate revealed atypical cells, which is suggestive of metastatic breast carcinoma. A bone marrow biopsy revealed marked fibrosis and pleomorphic neoplastic cells. Tumor cells were positive for CAM 5.2, AE1/3, Her-2/neu (3+), mammaglobin, GCDFP-15, and CK 7, which is consistent with metastatic breast carcinoma.

Figure 1.

Monomorphic atypical cells seen on histopathology of the liver.

Figure 2.

Atypical cells invading the breast stroma.

Systemic chemotherapy with docetaxel, cyclophos-phamide, trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech), and tamoxifen was initiated. The patient's LFTs normalized, and tumor marker studies, including carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 27-29, and CA 15-3, continued to decrease.

The patient was readmitted 6 months later with a 2-week history of personality changes and confusion. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement and multiple contrast-enhanced parenchymal nodules consistent with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. The patient's family opted for hospice care, and she was discharged to home hospice on the fourth hospital day.

Discussion

ALF is characterized by sudden liver dysfunction manifesting as coagulopathy and encephalopathy in an individual without preexisting liver disease who has an illness of less than 26 weeks' duration.1 ALF is a complex and urgent medical condition that poses diagnostic and treatment challenges.1 Although the most commonly identified causes of ALF are drug toxicities and viral hepatitis, the cause may remain elusive in as many as 20–40% of cases.1–3 Neoplastic infiltration of the liver as a cause of ALF is rare. Rowbotham and associates analyzed 4,020 ALF cases over an 18-year period and attributed only 0.44% of these cases to malignant hepatic infiltration.4

Liver metastases from both hematologic and solid organ malignancies have been reported to present as fulminant hepatic failure.5 Breast carcinoma has also been implicated.5,6 In our patient, acute onset of ascites, rapid and progressive elevation of LFTs, and evidence of coagulopathy drew attention toward a primary hepatic pathology and even possible fulminant hepatic failure; however, there was no evidence of encephalopathy. Moreover, the personality changes that developed were attributed to metastases to the brain. The presentation, however, closely mimicked ALF. To date, occult breast malignancy presenting as fulminant liver failure has been reported only twice in the English-language medical literature.7,8 In both instances, the diagnosis was made postmortem (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Occult Breast Cancer Cases That Presented as Acute Hepatic Decompensation

| Reference | Patient age (years) | Imaging results | Diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morrison WL, Pennington CR7 | 57 | USG: ill-defined area | At autopsy | Death in 2 weeks |

| Myszor MF, Record CO8 | 34 | Isotope scan: focal defect USG: hepatomegaly CT scan: normal |

At autopsy | Death in 6 days |

| The current case report | 38 | USG: heterogeneous liver CT scan: fatty liver, hepatomegaly, ascites |

On biopsy | Death in 6 months |

- CT

computed tomography

- USG

ultrasonography

Various mechanisms for hepatocellular damage from neoplastic hepatic infiltration have been proposed. Invasion of hepatic and portal vessels by tumor cells may result in ischemia and infarction.5 Tumor cells may exert a pressure effect on hepatocytes and compete for oxygen and nutrients, resulting in liver necrosis. Hemodynamic instability accompanying hepatic dysfunction may decrease effective arterial blood volume and further jeopardize hepatic blood flow.5

Although liver metastasis from breast carcinoma has been reported, fulminant hepatic failure from the spread of this tumor is rare and poses a diagnostic challenge.9,10 Clinical presentation, radiologic findings, and laboratory results are usually nonspecific, inconclusive, and unrevealing.5,10 Diagnosis is more challenging when the primary malignancy is occult. Typical radiologic features of hepatic infiltration from a malignancy are target lesions on ultrasonography and irregular areas of low attenuation on contrast-enhanced CT.10 As with our patient, imaging may be nonspecific, without any focal abnormality of the liver parenchyma.10 Hepatomegaly and ascites may be the only radiologic findings, as with any other cause of ALF.10 LFTs may not rise in concordance with the amount of tumor infiltration, causing the degree of hepatic involvement to be underestimated.5 The cause of the discordance between the degree of tumor infiltration and radiologic liver findings has been suggested by findings from autopsy studies. In cases where there has been acute hepatic decompensation, tumor cells have been found to invade diffusely into liver sinusoids. This finding contrasts the intense, but more focal, parenchymal infiltration usually found on pathology in the majority of metastatic tumor invasion cases.10 Given that hepatic parenchyma is not involved, the liver surface tends to be smooth, with no masses or nodularity, despite a significant degree of tumor invasion.6,10 Hence, typical findings such as target lesions are not seen on radiologic imaging.10

Because clinical presentation and noninvasive investigations may not be diagnostic, liver biopsy is the definitive procedure of choice. The morphologic and immunophenotypic changes found on the liver biopsy of our patient's occult breast carcinoma guided us toward a definitive diagnosis and resulted in rapid initiation of a specific therapy. Early diagnosis has therapeutic as well as prognostic implications. Most cases of ALF from neoplastic hepatic infiltration have an extremely poor prognosis, with death occurring within several days of clinical presentation. Myszor and Record reviewed 25 cases of ALF from hepatic infiltration secondary to hematologic and solid organ malignancies and reported a 100% mortality rate at a mean period of 7.8 days from the time of hospitalization.8 Allison and coworkers reviewed cases of breast carcinoma with diffuse hepatic infiltration and reported a mortality rate of 90%, with death occurring from 3 days to 2 months after presentation.6 In contrast to previously reported dismal prognoses, our patient survived for 6 months after diagnosis. We believe that early initiation of targeted therapy lengthened the survival of our patient. This case underscores the need for urgent liver biopsy, particularly if work-up for common causes, such as toxins and viral hepatitis, is negative. A high index of clinical suspicion is necessary to institute etiology-targeted therapy that may prolong survival.

Footnotes

The authors thank Dr. Kun Ru, of Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for help with pathology slides.

References

- 1. Polson J. Lee WM; American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:1179–1197. doi: 10.1002/hep.20703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–954. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yee H, Lidofsky S. Fulminant hepatic failure. In: Feldman M, Sieisenger M, Scharschmidt E, editors. Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders; 1998. pp. 1355–1364. Vol 2. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rowbotham D, Wendon J, Williams R. Acute liver failure secondary to hepatic infiltration: a single centre experience of 18 cases. Gut. 1998;42:576–580. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rajvanshi P, Kowdley KV, Hirota WK, Meyers JB, Keeffe EB. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to neoplastic infiltration of the liver. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:339–343. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155123.97418.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allison KH, Fligner CL, Parks WT. Radiographically occult, diffuse intrasinusoidal hepatic metastases from primary breast carcinomas: a clinicopathologic study of 3 autopsy cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1418–1423. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-1418-RODIHM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morrison WL, Pennington CR. Liver metastases from an occult breast carcinoma presenting as acute fulminant hepatic failure. Br J Clin Pract. 1984;38:273–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Myszor MF, Record CO. Primary and secondary malignant disease of the liver and fulminant hepatic failure. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:441–446. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199008000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carty NJ, Foggit A, Hamilton CR, Royle GT, Taylor I. Patterns of clinical metastasis in breast cancer: an analysis of 100 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1995;21:607–608. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(95)95176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roach H, Whipp E, Virjee J, Callaway MP. A pictorial review of the varied appearance of atypical liver metastasis from carcinoma of the breast. Br JRadiol. 2005;78:1098–1103. doi: 10.1259/bjr/16104611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]