Abstract

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), arising from mesenchymal cells, is the most common soft tissue tumour in children and accounts for up to half of all sarcomas. We present the case of a 33-year-old male presented to the urology department of the University College Hospital Galway (Ireland) in March 2009 with a 2-month history of a left scrotal swelling, increasing in size.

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas account for up to 3% of childhood cancers and up to 1% of adult cancers.1 A rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), arising from mesenchymal cells, is the most common soft tissue tumour in children and accounts for up to 50% of sarcomas.2 However, the incidence of RMS in adults is rare, accounting for only 3% of soft tissue sarcomas.3 Paratesticular RMS arises from the mesenchymal elements of the testes, epididymis and the spermatic cord. Paratesticular RMS represents 7% of all adult RMS according to the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS) Group.4 Classically, RMS presents as a painless scrotal mass.

Case report

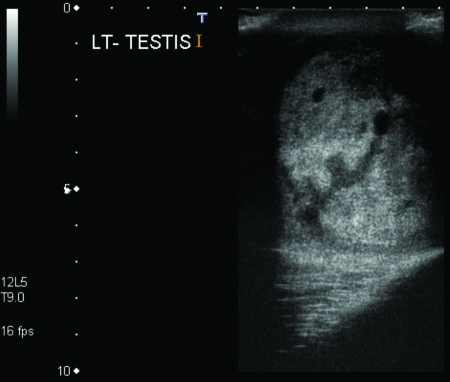

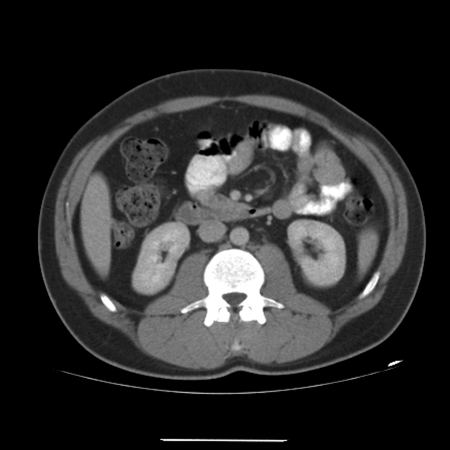

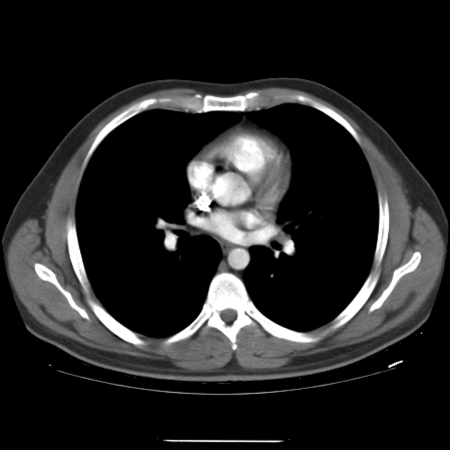

A 33-year-old male presented to the urology department of the University College Hospital Galway (Ireland) in March 2009 with a 2-month history of a left scrotal swelling, increasing in size. An ultrasound revealed a large tumour mass in the left testes, which was heterogeneous and contained foci of calcification (Fig. 1). Tumour markers were within normal limits (beta-human chorionic gonadotropin [βHCG] <1, alpha-fetoprotein [AFP] 2.5, Lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] 425). A computed tomography thorax abdomen pelvis (CT-TAP) scan revealed no metastases (Fig. 2) (Fig. 3) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound of left testicular mass with foci of calcification.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography of abdomen with no metastases.

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography of pelvis with no metastases.

Fig. 4.

Computed tomography of thorax with no metastases.

The following week, the patient underwent a routine left radical orchidectomy. The histopathology report showed an 11-cm poorly differentiated embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. The tumour focally involved the full thickness of the tunica albuginea and did not invade the tunica vaginalis. The resected margins were free of tumour as was the spermatic cord.

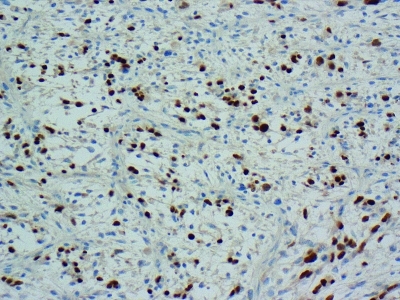

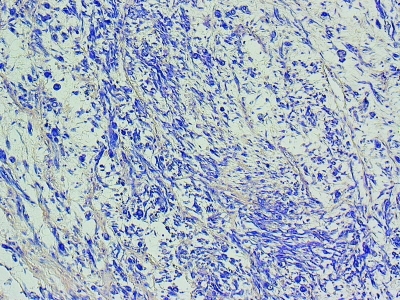

Germ cell markers and staining for AFP, HCG, placental alkaline phosphatase, C-kit, CD30, actin and desmin were negative. Immunohistochemical staining for myogenin (Fig. 5) and phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (Fig. 6) were positive supporting the diagnosis of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS).5

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma with myogenin.

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical staining of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma with phosphotungstic acid haematoxylin.

The myogenin gene codes for a specific phosphoprotein that induces the differentiation of mesenchymal cells from skeletal muscle. It has high nuclear positivity and is highly specific for ERMS. Phosphotungstic acid haematoxylin is also useful in this scenario, as it stains the rhabdomyoblasts a deep purple colour.

A RMS is a highly malignant tumour which can present with early metastases.6 As this was a late presentation of an aggressive, poorly differentiated tumour, a CT of the brain was performed which revealed no metastases. Following a multidisciplinary meeting, the patient underwent a course of adjuvant chemotherapy and was followed up postoperatively with a CT-TAP at 3 months. All CT-TAPs to this date reveal no metastases.

Discussion

In the international classification of rhabdomyosarcoma there are 5 recognized variants: embryonal, alveolar, botryoid embryonal, spindle cell embryonal and anaplastic.7 The most common variant is embryonal, most associated with tumours of the genitourinary tract and the head and neck. Histologically, the embryonal subtype resembles that of a 6- to 8-week old embryo. A RMS can be identified with the use of desmin stains and muscle specific actin stains and more recently myogenin.

In adults, RMS is an aggressive tumour with a high rate of metastasis. As embryonal RMS is rare in adults, the experience from the management of children is applied to the adult population; however, the prognosis is not as favourable.3 There are very few prognostic factors for the adult population. Prognostic factors for children include tumour size, resectability, age and lymph node involvement.

An RMS is staged according to the TNM system. T1 tumours are confined to the organ; T2 tumours invade adjacent structures. T1 and T2 are further divided into an A or B subset, depending on whether they are less than or greater than 5 cm. N0 is no nodal involvement, while, N1 represents regional lymph node involvement. M0 represents no metastasis, with M1 defining distant metastasis.

As there is limited research on the management of RMS in adults, management guidelines are taken from the IRS Group. The IRS management guidelines are based on a pediatric population (Table 1). As this patient had a tumour of 11 cm and the CT-TAP and brain scans were negative for metastasis, he was assigned the IRS stage 1. The patient then had surgical excision followed by chemotherapy. The chemotherapy regimen was ifosfamide, vincristine and actinomycin, as per the IRS protocol. The IRS protocol has resulted in reducing morbidity and increasing survival from 25% to 70% over 20 years since 1970.8

Table 1.

Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group Grouping System (11)

| Group | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Localized tumor, completely removed with pathologically clear margins and no regional lymph node involvement |

| II | Localized tumor, grossly removed with (a) microscopically involved margins Localized tumor, grossly removed with (b) involved, grossly resected regional lymph nodes Localized tumor, grossly removed with (c) both |

| III | Localized tumor, with gross residual disease after grossly incomplete removal, or biopsy only |

| IV | Distant metastases present at diagnosis |

There is limited long-term data on adults with ERMS of the testis. However, patient age at diagnosis is of prognostic value.9 Adults with RMS of any organ do have significantly poorer long-term outcomes in comparison to the pediatric population. The patient presented with an aggressive IRS Group 1 neoplasm; on review of the literature, it is not clear how many adult males present with IRS Group 1 of this rare aggressive tumour (Table 2). A review of 180 adult patients with RMS of any organ revealed that 149 had localized disease, with a further 31 patient having metastatic disease at diagnosis.10

Table 2.

Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group Staging System

| Stage | Site of primary tumour | Tumour size | Lymph nodes | Distant metastases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orbit, non-PM head/neck; GU nonbladder/prostate; biliary tract |

Any size | N0, N1 | M0 |

| 2 | All other sites | <5cm | N0 | M0 |

| 3 | All other sites | <5cm >5cm |

N1 N0 or N1 |

M0 M0 |

| 4 | Any site | Any size | N0 or N1 | M1 |

PM: parameningeal; GU: genitourinary; N0: no nodal involvement; N1: regional lymph node involvement; M0: no metastasis; M1: distant metastasis. Adapted from Raney et al.11

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) was not performed in this case as radiologically there was no lymphadenopathy (IRS group 1). However, RPLND in the absence of positive findings on radiological investigation remains controversial as lymph nodal involvement is a prognostic factor. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection eliminates the need for abdominal radiotherapy in patients in IRS group 2. Hermans and colleagues reported that RPLND provided accurate staging and subsequent RPLND combined with chemotherapy revealed excellent long-term results in IRS group 2.8 In this case, following discussion at a multi-disciplinary team meeting, RPLND was not recommended as this procedure is not routinely performed in Europe for IRS group 1 tumours.

Chemotherapy is used as an adjunct to surgery. The chemotherapy agents used are vincristine, actinomycin D and cyclophosphamide. Patients with unresectable tumours who undergo a treatment of chemotherapy should be considered for surgery after downgrading. Sentinel lymph node biopsy could benefit these particular patients.12

Radiotheraphy is recommended for patients with metastasis. No benefit with radiotherapy has been shown in patients with IRS group 1.4 Radiotherapy is useful post-surgery when there is residual microscopic or macroscopic residual tumour. Overall, the 5-year survival for adult RMS is 44%.6

Conclusion

An ERMS of the testes is a rare pathological finding in an adult. As there is limited research on this form of cancer, the management strategies are dictated by research on ERMS in the pediatric population. These tumours are aggressive and grow rapidly, therefore early diagnosis and management are essential to improving the prognosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Herzog CE. Overview of sarcomas in the adolescent and young adult population. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:215–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000161762.53175.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arndt CA, Crist WM. Common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:342–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907293410507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuneyt U, Hakan B, Okan K. A cohort study of adult rhabdomyosarcoma: a single institution experience. WJMS. 2008;3:54–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raney RB, Jr, Hays DM. Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood. Cancer. 1978;42:729–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197808)42:2<729::aid-cncr2820420246>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosai J. Rosai and Ackerman’s surgical pathology. 9th edition. New York: NY: Elsevier; 2004. Soft tissues; pp. 2301–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little DJ, Ballo MT, Zagars GK, et al. Adult rhabdomyosarcoma: Outcome following multimodality treatment. Cancer. 2002;95:377–88. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qualman S, Lynch J, Bridge J, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of anaplasia in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma : a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2008;113:3242–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermans BP, Foster S. Is retroperitoneal lymph node dissection necessary for adult paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma? J Urol. 1998;160 (6 Pt 1):2074–7. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199812010-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari A, Bisogno G, Casanova M, et al. Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma: report from the Italian and German cooperative group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:449–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrari A, Dileo P, Casanova M, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma in adults. A retrospective analysis of 171 patients treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2003;98:571–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raney RB, Maurer HM, Anderson JR, et al. The Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group (IRSG): Major Lessons From the IRS-I Through IRS-IV Studies as Background for the Current IRS-V Treatment Protocols. Sarcoma. 2001;5:9–15. doi: 10.1080/13577140120048890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neville HL, Andrassy RJ, Lally KP, et al. Lymphatic mapping with sentinel node biopsy in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:961–4. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.6936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]