Abstract

Background: Genetic analysis is commonly performed in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency.

Study Objective: The objective of the study was to describe comprehensive CYP21A2 mutation analysis in a large cohort of CAH patients.

Methods: Targeted CYP21A2 mutation analysis was performed in 213 patients and 232 parents from 182 unrelated families. Complete exons of CYP21A2 were sequenced in patients in whom positive mutations were not identified by targeted mutation analysis. Copy number variation and deletions were determined using Southern blot analysis and PCR methods. Genotype was correlated with phenotype.

Results: In our heterogeneous U.S. cohort, targeted CYP21A2 mutation analysis did not identify mutations on one allele in 19 probands (10.4%). Sequencing identified six novel mutations (p.Gln262fs, IVS8+1G>A, IVS9-1G>A, p.R408H, p.Gly424fs, p.R426P) and nine previously reported rare mutations. The majority of patients (79%) were compound heterozygotes and 69% of nonclassic (NC) patients were compound heterozygous for a classic and a NC mutation. Duplicated CYP21A2 haplotypes, de novo mutations and uniparental disomy were present in 2.7% of probands and 1.9 and 0.9% of patients from informative families, respectively. Genotype accurately predicted phenotype in 90.5, 85.1, and 97.8% of patients with salt-wasting, simple virilizing, and NC mutations, respectively.

Conclusions: Extensive genetic analysis beyond targeted CYP21A2 mutational detection is often required to accurately determine genotype in patients with CAH due to the high frequency of complex genetic variation.

Extensive genetic analysis is often required to accurately determine genotype in patients with CAH due to the high frequency of complex CYP21A2 genetic variation.

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is an autosomal recessive disorder of cortisol biosynthesis. Approximately 95% of cases are due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency (1), which is characterized by cortisol deficiency with or without aldosterone deficiency, and androgen excess. The clinical phenotype is classified as classic, the severe form, and nonclassic (NC), the mild form. Classic CAH occurs in 1:10,000 to 1:16,000 live births in most populations (2,3) and is subclassified as salt-wasting (SW) or simple virilizing (SV), reflecting the degree of aldosterone deficiency. The incidence of NC CAH is less well defined but is estimated to be approximately 1:1000 (4,5).

The gene encoding 21-hydroxylase, CYP21A2, is mapped to the short arm of chromosome 6 (6p21.3) within the human leukocyte antigen complex, and, with neighboring genes for tenascin (TNX), complement (C4), and the serine threonine nuclear protein kinase (RP), forms a genetic unit termed RCCX (RP-C4-CYP21-TNX) (5). Two thirds of RCCX haplotypes have been reported to be bimodular units, 135 kb in length, including a genomic DNA segment of approximately 30 kb that is composed of pseudogenes RP2, CYP21A1P, TNXA, and another active copy of C4 (long or short) gene (6). CYP21A1P shares 98% homology in the coding sequence with CYP21A2. Monomodular, trimodular, and quadrimodular haplotypes have also been described (6,7,8,9,10).

Mutations causing 21-hydroxylase deficiency typically arise from unequal recombination events between CYP21A2 and CYP21A1P, termed gene conversion. The majority of mutations are due to the transfer of short pseudogene sequences to CYP21A2 during meiosis (11). In addition, approximately 25% of alleles carry either a deletion or a large deletion spanning approximately 30 kb, which is due to meiotic recombination between the 3′ end of CYP21A1P through the 5′ end of CYP21A2 producing a nonfunctional chimeric gene (12,13,14). The high rate of genetic variability at this locus, the presence of CYP21A2 gene duplications, and the presence of the CYP21A1P pseudogene complicate the determination of disease and carrier status.

Most patients with CAH are compound heterozygous for disease-causing mutations. The clinical phenotype is generally related to the less severely mutated allele and consequently to the residual 21-hydroxylase activity (13). Several studies have suggested high concordance rates (80–90%) between genotype and phenotype (13,14,15,16).

The aim of our study was to describe a comprehensive CYP21A2 mutation analysis in a large cohort of CAH patients and determine the frequency of genetic variations that complicate the accuracy of routine genotyping of patients. We also performed genotype-phenotype correlation.

Patients and Methods

Patients

From 2006 to 2009, 213 patients (102 males, 111 females, aged 1–65 yr) with CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency (110 SW, 56 SV, 47 NC) were enrolled in a Natural History Study at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD (clinical trials no. NCT00250159). All patients and 232 parents from 182 unrelated families were genotyped. Phenotypic classification was determined by one pediatric endocrinologist (D.P.M.) based on clinical and hormonal criteria and a retrospective review of each patient’s medical records. In general, the classic SW form of CAH was defined as having an adrenal crisis with documented hyperkalemia and hyponatremia, ambiguous genitalia in females, and elevated basal serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone and plasma renin activity at diagnosis or during a later evaluation. Females with ambiguous genitalia, elevated basal serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone but without evidence of SW, or in whom early virilization was diagnosed at an age beyond the neonatal period were classified as having the SV form. Males who developed early signs and symptoms of hyperandrogenism, elevated serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone, but without evidence of SW were classified as SV. With the advent of neonatal screening programs, this phenotypic subclassification of classic CAH may not be necessary. In general, females with normal genitalia and patients who developed signs and symptoms of hyperandrogenism after 4 yr of age and had an abnormal ACTH stimulation test [17-hydroxyprogesterone > 1200 ng/dl (36 nmol/liter)] were classified as having the NC form. The study was approved by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Institutional Review Board. All adult subjects and parents of participating adolescents gave written informed consent. All minors gave their assent.

CYP21A2 mutation analysis

DNA was extracted (Gentra Puregene kit; QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and analyzed for the 12 most common CYP21A2 mutations [p.P30L, IVS2-13A/C>G, exon 3, 8 bp deletion (p.G110Efs), p.I172N, exon 6 cluster (p.I236N, p.V237E, p.M239K), p.V281L, p.Leu307fs, p.Q318X, p.R356W, and p.P453S] using the multiplex minisequencing method (17). The same method was used to screen for heterozygosity of 12 single nucleotide polymorphic markers across CYP21A2 (F. K. Fujimura, unpublished data). Primers specific for the 5′ region of CYP21A1P (17) and for exon 6 of CYP21A2 (18) were used to detect the 30-kb deletion. Homozygous deletion of CYP21A2 was indicated by the absence of amplification for the CYP21A2 gene-specific PCR and by amplification of only the exon 3 segment of CYP21A1P (17). When possible, mutation analysis of the parents (n = 232) was performed to assist in determining or confirming the patient genotype.

CYP21A2 sequencing

DNA was sequenced from patients with known CAH by hormonal testing and only one mutation detected by PCR-based targeted mutation analysis. Sequencing was completed using ABI Big Dye Terminator version 3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on the ABI 310 genetic analyzer and compared against the reference CYP21A2 sequence (reference sequence NM_000500.5).

Deletion and duplication analysis

DNA extraction and Southern blotting were performed according to established protocol (19). Restriction enzymes TaqI and PshAI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were used. PshAI digestion provides information regarding the RP1 to RP2 ratio that allows a calculation for the length of the RCCX module. In addition to probes E and F as previously described (19), a novel probe for RP gene was created from human genomic DNA (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) by amplification of a 743-bp fragment that corresponds to the terminal sequences of both RP1 and RP2 using a pair of primers 5′-CACCTTTCCCCTTTCCTGT-′ and 5′-ATCCCACCTTCCTATTTCAA-3′. RCCX module copy numbers were interpreted based on relative band intensities in the same electrophoretic line using densitometry and National Institutes of Health ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD).

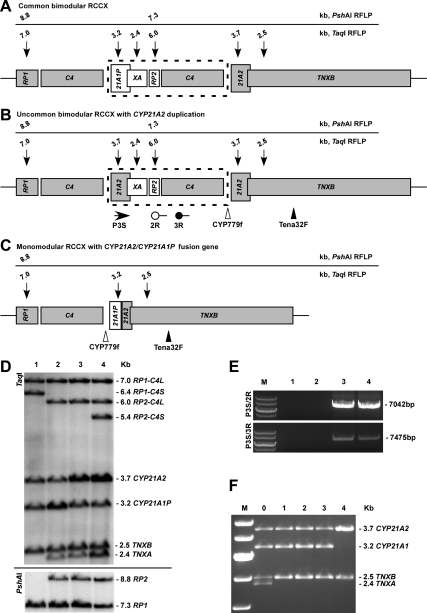

The PCR methods described previously were used to confirm Southern blot regarding CYP21A2 duplication (7) and fusion genes (20), respectively (Fig. 1, E and F). Quantitative real-time PCR, using published (21,22) and newly designed primers (forward: 5′-CGTTGGTCTCTGCTCTGGAAA-3′; reverse: 5′-GCCCAGCCTTACCTCACAGA-3′), also confirmed copy number variations (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of RCCX modules and representative Southern blots and PCR results for detecting CYP21A2 duplications and unusual haplotypes. Active genes are shown in gray. Sizes and locations of the restriction fragments are annotated with arrows. C4 genes can be long (C4L) or short (C4S). The schematic is shown for C4L only. The size of sequence in the dashed frame is 30 kb. The schematic diagram shows a common bimodular RCCX (A); an uncommon bimodular RCCX with an additional copy of CYP21A2 gene linked to the pseudogene XA, and PCR amplification using primer pairs P3S/2R and P3S/3R are positive for duplicated CYP21A2 allele but negative for common RCCX modules (7) (B); a monomodular RCCX with 21A2/21A1P fusion gene resulting from a 30-kb deletion, in which junction sites can vary, and an 8515-bp PCR product amplified by primers CYP779f/Tena32F was digested by TaqI to detect fusion genes (20) (C); RCCX haplotype was demonstrated by TaqI restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP; upper panel) and confirmed by PshAI RFLP for the RP gene (lower panel). For the C4 gene, the TaqI digest for C4L form results in fragment sizes of 7.0 and 6.0 kb, and C4S results in fragments of 6.4 and 5.4 kb. Focusing on the CYP21 genes, patient 1 demonstrates equal signal densities for CYP21A2 and CYP21A1P. Patient 2 carries a CYP21A2/CYP21A1P fusion gene (30 kb deletion), in which the CYP21A2 to CYP21A1P ratio is reduced. Patient 3 has three copies of CYP21A2, shown by an increased CYP21A2 to CYP21A1P ratio. The CYP21A2 duplication allele was inherited from patient 4 (the father) (D). E, Two pairs of primers specifically amplify the CYP21A2 duplication allele. Patients 1 and 2 are negative for the duplication, whereas patient 3 and subject 4 (the father) are positive. F, TaqI digestion patterns of 8515-bp PCR products for detecting large gene deletion that can result in TNXB/XA or CYP21A2/CYP21A1P fusion genes. Subject 0 is a patient who was previously reported to carry a gene deletion involving both CYP21A2 and TNXB genes that was demonstrated by four bands (54). Subjects 1–3 are all carriers of a gene deletion involving only CYP21A2 that was shown by two bands for CYP21 and a single band for TNXB. Subject 4 is negative for gene deletion. 21A2, Active gene CYP21A2; 21A1P, pseudogene CYP21A1P; RP1, serine/threonine nuclear kinase gene; RP2, a gene fragment of RP1; TNXB, extracellular matrix protein tenascin-X gene; TNXA (or XA), truncated tenascin pseudogene.

Genotype-phenotype correlation

To assess genotype-phenotype correlation, disease-causing mutations were divided into four groups according to expected 21-hydroxylase activity based on published in vitro studies (13,16,23). Group 0 included patients with null mutations (gene deletions, p.G110Efs; exon 6 cluster, p.Leu307fs, p.Q318X, p.R356W; and novel frame shift mutations) on both alleles. Group A included patients homozygous for IVS2-13A/C>G or compound heterozygous for IVS2-13A/C>G and a null mutation. IVS2-13A/C>G is known to have minimal residual enzymatic activity (24). Group B included patients with p.I172N and p.I77T mutations (25) (∼2% residual enzymatic activity), homozygous or compound heterozygous with groups 0, or A mutations. Group C included patients with p.P30L, p.V281L, and p.P453S mutations (∼20–60% residual enzymatic activity) (26), homozygous or compound heterozygous with groups 0, and A or B mutations. Group D included patients with mutations not yet evaluated for their influence on enzymatic activity and undetermined mutations. The expected phenotype associated with groups 0 and A was SW, groups B and C, was SV and NC, respectively.

Genotype-phenotype correlation was assessed for the entire population since phenotype was not always consistent within families. Positive predictive value was calculated and equals the number of patients with the expected phenotype for each group divided by the total number of patients in that group, multiplied by 100.

Results

Clinical presentation at diagnosis

Most patients were diagnosed before neonatal screening programs (Table 1). Seven classic CAH females had ambiguous genitalia that was missed at birth: two were diagnosed by newborn screening, and four were diagnosed following an adrenal crisis at 7, 8, 14, and 35 d of life. Two of these infants were initially thought to be healthy males. A female born in 1953 presented with ambiguous genitalia and significant virilization at age 10 yr and was determined to have SV CAH. The majority (61.0%) of SW males were diagnosed after a neonatal adrenal crisis (mean age at diagnosis: 20 ± 11 d) and most (81.8%) SV males were diagnosed as toddlers due to pubic hair and/or increased growth velocity. About one third of NC females and the majority of NC males were diagnosed during childhood (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical presentation at diagnosis of 213 patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency

| SW

|

SV

|

NC

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation | Female (n = 51) | Male (n = 59) | Female (n = 23) | Male (n = 33) | Female (n = 37) | Male (n = 10) |

| Ambiguous genitalia | 42 | 19 | 1 | |||

| Adrenal crisis | 4 | 36 | ||||

| Newborn screening | 2 | 13 | 3 | |||

| Prenatal screening | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Family history/genetic testing | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 2 | |

| Pubic hair and/or growth spurt | 1 | 27 | 13 | 7 | ||

| Irregular menses ± hirsutism, acne | 13 | |||||

| Infertility | 2 | |||||

| Other | 1a | |||||

Diagnosed at age 10 yr with significant virilization.

All of our NC patients for whom we have hormonal data at the time of diagnosis would have been identified and diagnosed with NC CAH based on the recently proposed cutoff of 200 ng/dl (6 nmol/liter) for basal 17-hydroxyprogesterone (27). Among our NC patients, the lowest basal 17-hydroxyprogesterone was 231 ng/dl (7 nmol/liter), and the lowest 17-hydroxyprogesterone after a 60-min cosyntropin test was 1360 ng/dl (41 nmol/liter).

Mutation analysis

Our cohort carried the full spectrum of known mutations (Tables 2 and 3). The majority of patients (79%) were compound heterozygotes. Gene deletions were found in 111 alleles, with a relative frequency of 30.5%. Single-point mutations were detected in 224 alleles (61.5%). Classic mutations were present in 69% of NC patients.

Table 2.

Frequency of allelic CYP21A2 mutations by phenotype in 182 unrelated patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency

| CYP21A2 mutationa | Number of alleles (% of alleles)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW | SV | NC | Total | |

| p.P30L (c.92C>T) | 3 (3.8) | 3 (0.8) | ||

| p.I77T (c.233T>C)b | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| IVS2-13A/C>G (c.293-13A/C>G) | 62 (33.0) | 18 (18.4) | 5 (6.4) | 85 (23.4) |

| IVS2-13A/C>G + a second mutation (c.293-13A/C>G) | 4 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.3) | 6 (1.6) |

| p.G110Efs (c.332_339del) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| p.G110Efs, p.V281L (c.332_339del, c.844G>T) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| p.Ser170fs (c.511_512insA)b | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.I172N (c.518T>A) | 4 (2.1) | 35 (35.7) | 7 (9.0) | 46 (12.6) |

| p.I172N + other mutations (c.518T>A) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (3.1) | 4 (1.1) | |

| Exon 6 cluster: p.I236N, p.V237E, p.M239K (c.710T>A, c.713T>A, c.719T>A) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.0) | 4 (1.1) | |

| p.Gln262fs (c.787_788insC)c | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.V281L (c.844G>T) | 1 (1.0) | 45 (57.7) | 46 (12.6) | |

| p.Leu307fs (c.923_924insT) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.Leu307fs, p.Q318X (c.923_924insT, c.955C>T) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | |

| p.Q318X (c.955C>T) | 6 (3.2) | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.8) | 12 (3.3) |

| p.R356W (c.1069C>T) | 6 (3.2) | 6 (6.1) | 1 (1.3) | 13 (3.6) |

| p.H365Y (c.1096C>T)b | 3 (1.6) | 3 (0.8) | ||

| IVS8 + 1G>A (c.1118+ 1G>A)c | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.W405X (c.1217G>A)b | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| IVS9-1G>A (c.1223-1G>A)c | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.R408H (c.1226G>A)c | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.Gly424fs (c.1272_1276del)c | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.R426C (c.1279C>T)b | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.R426P (c.1280G>C)c | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.R444X (c.1333C>T)b | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.P453S (c.1360C>T) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| p.P482S (c.1447C>T)b | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| p.R483P (c.1451G>C)b | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | |

| p.Arg483fs (c.1450_1451insC)b | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Deletion or 30-kb deletion | 81 (43.1) | 21 (21.4) | 9 (11.5) | 111 (30.5) |

| Duplication | 3 (1.6) | 2 (2.0) | 5 (1.4) | |

| Indeterminated | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Total | 188 | 98 | 78 | 364 |

Common mutations are listed in bold.

Nomenclature corresponding to the protein is based on conventional codon numbering. Nomenclature based on cDNA and that of six new mutations are based on RefSeq NM_000500.5.

Rare mutations, detected by sequencing.

Novel mutations, detected by sequencing.

Due to lack of parental DNA (n = 1) or lack of patient DNA (n = 1).

Table 3.

Genotype and phenotype in 213 patients with CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency

| Genotype | Copy 1 | Copy 2 | Copy 3 | Phenotype

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW | SV | NC | ||||

| Group 0 | Deletion or 30-kb deletion | Deletion or 30-kb deletion | 21a | 2 | ||

| Deletion or 30-kb deletion | p.G110Efs, p.V281L | 2 | ||||

| Deletion or 30-kb deletion | p.Q318X | 2 | ||||

| 30-kb deletion | IVS8+ 1G>Ab | 1 | ||||

| 30-kb deletion | p.R426C | 1 | ||||

| Deletion | IVS2-13A/C>G, p.V281L | 3c | ||||

| Deletion | Exon 6 cluster | 1 | ||||

| Deletion | p.R356W | 1 | 1 | |||

| Deletion | p.H365Y | 1 | ||||

| Deletion | p.R444X | 1 | ||||

| Deletion | p.R483P | 1 | ||||

| Deletion | p.Arg483fs | 1 | ||||

| p.G110Efs | p.R356W | 1 | ||||

| p.I172N, exon 6 cluster | p.Leu307fs, p.Q318X | 1 | ||||

| p.I172N, p.G110Efs | 30-kb deletion | p.I172N, exon 6 cluster, p.Leu307fs, IVS2-13A/C>G, p.Q318X | 1 | |||

| p.I172N, exon 6 cluster, p.V281L, p.Leu307fs, p.Q318Xd | p.I172N, exon 6 cluster, p.V281L, p.Leu307fs | 2e | ||||

| Exon 6 cluster | p.Leu307fs, p.Q318X | 1 | ||||

| Group A | IVS2-13A/C>G | Deletion or 30-kb deletion | 34f,g | 3e,g | ||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | 30-kb deletion | p.Q318X | 1 | |||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | IVS2-13A/C>G | 8 | 1 | |||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | IVS2-13A/C>G, p.V281L | 2e | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | IVS2-13A/C>G, p.P453S | 1 | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | p.G110Efs | 1 | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | p.Ser170fs | 1 | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | Exon 6 Clstr | 1 | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | p.Gln262fsb | 1 | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | p.Q318X | 3e | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | p.R356W | 4 | 2 | |||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | p.H365Y | 3e | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | p.W405X | 1 | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | IVS9-1G>Ab | 1 | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | p.Gly424fsb | 1 | ||||

| IVS2-13A/C>G, p.P453S | p.Q318X | 2e | ||||

| Group B | p.l172N | Deletion or 30-kb deletion | 3e,g | 13f,g | ||

| p.l172N | 30-kb deletion | p.I172N, exon 6 cluster, p.V281L, p.Leu307fs | 2 | |||

| p.l172N | IVS2-13A/C>G | 1 | 8 | 1 | ||

| p.l172N | IVS2-13A/C>G, p.V281L | 2e | ||||

| p.l172N | p.I172N | 3 | 1 | |||

| p.l172N | Exon 6 cluster | 1 | ||||

| p.l172N | Exon 6 cluster, p.V281L, p.Leu307fs | IVS2-13A/C>G | 1 | |||

| p.l172N | p.Leu307fs | 1 | ||||

| p.l172N | p.Q318X | 1 | 3 | |||

| p.l172N | p.R356W | 4e | ||||

| p.l172N | p.R483P | 1 | ||||

| p.l77T | Deletion | 1 | ||||

| Group C | p.V281L | Deletion or 30-kb deletion | 9e | |||

| p.V281L | IVS2-13A/C>G | 3 | ||||

| p.V281L | IVS2-13A/C>G, p.V281L | 1 | ||||

| p.V281L | p.I172N | 5e,c | ||||

| p.V281L | p.I172N, p.V281L | 1 | ||||

| p.V281L | p.V281L | 16a,c | ||||

| p.V281L | p.Q318X | 3 | ||||

| p.V281L | p.R356W | 1 | ||||

| p.V281L | p.R426Pd | 1 | ||||

| p.V281L | p.P453S | 1 | ||||

| (Continued) | ||||||

Table 3A.

Continued

| Genotype | Copy 1 | Copy 2 | Copy 3 | Phenotype

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW | SV | NC | ||||

| p.V281L | p.P482S | 1 | ||||

| p.P30L | Deletion | 1 | ||||

| p.P30L | IVS2-13A/C>G | 1 | ||||

| p.P30L | p.I172N | 1 | ||||

| p.P453S | p.I172N | 1 | ||||

| Group D | IVS2-13A/C>G | p.R408Hd | 2e | |||

| IVS2-13A/C>G | Undeterminedh | 1 | ||||

| p.l172N, p.P453S | Deletion | 1 | ||||

| Total | 110 | 56 | 47 | |||

Two pairs of siblings included;

novel mutation;

includes set of three siblings;

CYP21A2 duplication, distribution of mutations among alleles is unknown due to lack of DNA;

one pair of siblings included;

five pairs of siblings included;

siblings with different phenotypes included;

undetermined due to lack of patient DNA.

Targeted mutation analysis did not identify mutations on one allele in 19 probands (10.4%). Mutations were identified on the other allele. One of these patients was lost to follow-up, and DNA was not available for sequencing. Complete exon sequencing identified disease-causing mutations in all other patients including nine previously reported rare mutations in 12 probands: p.I77T in exon 2 (25), p.Ser170fs in exon 4 (28), p.H365Y (n = 3) in exon 8 (28), p.W405X in exon 9 (29) and p.Arg483fs (30), p.P482S (31), p.R444X (32,33), p.R426C (34), and p.R483P (n = 2) in exon 10 (35,36).

Six novel point mutations were identified by sequencing: p.Gln262fs (c.787_788insC) in exon 7, IVS8 + 1G>A (c.1118+G>A) in intron 8, IVS9-1G>A (c.1223-1G>A) in intron 9, p.R408H (c.1226G>A) in exon 10, p.Gly424fs (c.1272_1276del) in exon 10, and p.R426P (c.1280G>C) in exon 10. Patients with p.Gln262fs/IVS2-13A/C>G, IVS8 + 1G>A/deletion, IVS9-1G>A/IVS2-13A/C>G, and p.Gly424fs/IVS2-13A/C>G mutations had SW CAH. Two siblings with the p.R408H/IVS2-13A/C>G mutations had SV CAH, and one patient carrying p.R426P/p.V281L mutations had NC CAH.

Genotype phenotype correlation

Genotype accurately predicted phenotype in 88.9% of the patients in group 0, 91.5% in group A, 85.1% in group B, and 97.8% in group C. Genotype-phenotype discordance occurred in 19 patients (Tables 3 and 4). Ten patients with a SV phenotype had mutations typically associated with SW CAH, including four patients with homozygous null mutations. Two NC females had mutations typically associated with SV CAH. These two females had normal genitalia but did have generous basal 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels at diagnosis (Table 4). Conversely, five patients with mutations associated with SV CAH clinically displayed the SW form, and one female with a NC genotype was born with ambiguous genitalia.

Table 4.

Clinical data for patients with genotype-phenotype discordance

| Patient | Genotype group | Genotype | Phenotype | Gender | Clinical data at presentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | Deletion/p.R356W | SV | M | 46XX diagnosed at 3 yr 6 months due to ambiguous genitalia and pubic hair. Raised as male. |

| 2 | 0 | Deletion/30-kb deletion | SV | M | Pubic hair at 4 yr; basal 17OHP 3,174 ng/dl. Bone age 11 yr 6 months. |

| 3 | 0 | 30-kb deletion/30-kb deletion | SV | M | Growth acceleration at <5 yr; basal 17OHP 16,946 ng/dl. |

| 4 | 0 | Exon 6 cluster/p.Leu307fs, p.Q318X | SV | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Normal electrolytes off treatment as an infant. |

| 5 | 0 | p.I172N, p.G110Efs/30-kb deletion/p.I172N, exon 6 cluster, p.Leu307fs, IVS2-13A/C>G, p.Q318X | SV | M | Pubic hair at 4 yr; basal 17OHP 7,860 ng/dl; PRA elevated at 11.7 ng/ml/h. Bone age 10 yr. |

| 6 | A | IVS2-13A/C>G/deletion | SV | M | Pubic hair at 3 yr 5 months when younger brother diagnosed with CAH after a neonatal SW crisis. |

| 7 | A | IVS2-13A/C>G/deletion | SV | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Electrolytes normal while off fludrocortisone. No history of adrenal crises. |

| 8 | A | IVS2-13A/C>G/IVS2-13A/C>G | SV | F | Ambiguous genitalia. No history of SW crisis despite being off medication for >10 yr. |

| 9 | A | IVS2-13A/C>G/p.R356W | SV | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Initially thought to be healthy male. No SW crisis despite lack of neonatal treatment. |

| 10 | A | IVS2-13A/C>G/p.R356W | SV | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Diagnosed at 3 yr 11 months; basal 17OHP 36,123 ng/dl. |

| 11 | A | IVS2-13A/C>G/30-kb deletion | SV | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Presented at 10 yr with significant virilization. Pubic hair since 5 yr. |

| 12 | B | p.I172N/deletion | SW | M | Adrenal crisis at 1 wk. |

| 13 | B | p.I172N/deletion | SW | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Adrenal crisis at 6 months. |

| 14 | B | p.I172N/deletion | SW | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Adrenal crisis at 6 wk. |

| 15 | B | p.I172N/IVS2-13A/C>G | SW | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Adrenal crisis at 6 wk and multiple times during the first year. |

| 16 | B | p.I172N/p.Q318X | SW | F | Ambiguous genitalia. Adrenal crises at 7 d and 4 wk. |

| 17 | B | p.I172N/p.I172N | NC | F | Normal genitalia. Diagnosed at 7 yr due to increased growth and pubic hair. Basal 17OHP 3,557 ng/dl. |

| 18 | B | p.I172N/IVS2-13A/C>G | NC | F | Normal genitalia. Diagnosed at 5 yr 4 months with increased growth velocity. Basal 17OHP 5,541 ng/dl. |

| 19 | C | p.V281L/p.V281L, p.I172N | SV | F | Born with ambiguous genitalia. No adrenal crises. |

M, Male; F, female; 17OHP, 17-hydroxyprogesterone; PRA, plasma renin activity. Conversion factor for SI unit calculation: for 17OHP, multiply nanograms per deciliter by 0. 0302 to find nanomoles per liter.

Three pairs of siblings, one with a SW genotype (IVS2-13A/C>G/deletion) and two with a SV genotype (p.I172N/deletion) had discrepant phenotypes. In two families, the older male sibling was diagnosed as a toddler with SV CAH, and the younger sibling was diagnosed after a neonatal SW adrenal crisis. In the third family, the older sibling was diagnosed at 4 yr with SV CAH. The younger sibling was diagnosed in utero and was started on hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone after birth but was not given salt supplementation, and had a SW adrenal crisis at 6 wk (Na 127 mmol/liter, K 6.1 mmol/liter).

Unusual haplotypes

Five probands (2.7%) and six parents (2.6%) carried CYP21A2 duplications (Fig. 1). Interestingly, three of five probands with duplication appeared to have a common haplotype at the allele carrying two copies of CYP21A2; one of the copies carried p.I172N and a cluster of pseudogene-derived mutations in exon 6 (p.I236N, p.V237E, p.M239K) and exon 7 (p.V281L, p.Leu307fs). Two patients had SV CAH, and one had SW CAH; ethnicities were Western European, unknown, and mixed (Western European, Hispanic, African-American). Of the two remaining patients with duplication, one had SW CAH and carried three severe CYP21A2 mutations, and the other had SV CAH with p.I172N on one gene (Table 3).

All parents with CYP21A2 duplications had genetic reports based on targeted mutation analysis, which could be consistent with the disease state. The unaffected status was confirmed hormonally by ACTH stimulation testing in two parents; 17-hydroxyprogesterone at 60 min was 506 ng/dl (15.3 nmol/liter) and 351 ng/dl (10.6 nmol/liter). p.Q318X, a classic mutation widely associated with duplicated CYP21A2 haplotypes (37), was found in four of six parents carrying a CYP21A2 duplication. In these parents, p.Q318X was on the duplicated allele with a normal CYP21A2 and did not represent a disease-causing allele.

De novo mutations

Two SV females carried de novo mutations. Both patients presented with ambiguous genitalia. One patient was heterozygous for IVS2-13A/C>G and a de novo p.I172N. Her father was heterozygous for IVS2-13A/C>G and her mother was negative for both mutations. The second patient had two mutations inherited from her mother, p.P453S and p.I172N, and a de novo deletion. Because the mother had two mutations, one possible explanation was that she had CAH. However, parental and patient Southern blot analysis confirmed a de novo deletion in the proband and a maternal monomodular RCCX haplotype. No mutation was detected in the father. In both patients, maternity and paternity were confirmed by testing independent markers in several chromosomes, including chromosome 6.

We previously reported uniparental disomy (UPD) as the cause of CAH (38). This patient had SW CAH due to UPD of chromosome 6 and Klinefelter syndrome due to multiple episodes of nondisjunction. In our extensive genetic analysis of this cohort of patients and parents, our previously reported patient was the only patient who had CAH due to UPD.

Discussion

In our comprehensive mutation analysis of a large cohort of patients with CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency enrolled in a natural history study at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD, we commonly encountered complex CYP21A2 variation. The widely used PCR-based CYP21A2 analysis that targets most common mutations failed to identify mutations more often than expected. Complete gene resequencing was necessary to identify these mutations. In addition, five patients and six parents had CYP21A2 duplications, which interfere with the accuracy of routine genetic analysis. We also identified six novel CYP21A2 mutations, two de novo mutations, and one patient with UPD (38). Our data suggest that exhaustive genetic testing may need to be performed in some patients with CAH to provide accurate genetic counseling.

As expected, clinical presentation showed a spectrum of phenotypes. The majority of our patients were diagnosed before the implementation of newborn screening, which should alleviate the problem of late diagnosis of the classic patient. Although we identified mutations on both alleles in all but one patient, we were not able to explain some unusual discrepancies between phenotype and genotype.

Our genotype-phenotype correlation was best for group C, mutations associated with NC CAH. Poor genotype-phenotype correlation found in NC CAH in prior studies (13,16) was mostly due to the p.P30L mutation, and the majority of our patients carried p.V281L. Our genotype-phenotype findings were worst for group B, mutations associated with SV CAH. Our findings are somewhat similar to prior reports from Germany (13) and The Netherlands (14) that show divergence between observed and predicted phenotype in patients with p.I172N. However, these reports also showed excellent positive predictive value for patients with null mutations (13,14), and we report five SV patients with homozygous null mutations. It is possible that genetic variations in CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, other enzymes that have the ability to modulate salt balance in patients with CAH (39), or a combination of unknown factors that modify steroid action might explain some of our findings. This was not evaluated. In addition, p.I172N has a wide range of enzymatic activity possibly contributing to phenotypic variability. Lack of genotype-phenotype concordance might be attributed to variation in the IVS2-13A/C>G splice mutation (24,40) in a minority of patients. The presence of unusual hybrid genes (41) or promoter mutations (42,43) not detected by our methodology are additional possibilities.

A methodological drawback of our study is that the data from diagnosis were collected by a retrospective analysis of medical records, in combination with patient report. Most of our patients were diagnosed before newborn screening; the majority of salt wasters had a salt-losing adrenal crisis early in life and the majority of simple virilizers were diagnosed late. However, there is a continuum of disease severity, even among subtypes there is a possibility that some patients may not clearly fall into one phenotype category. Ultimately, management and treatment is based on clinical manifestations as well as hormonal measurements, not on genotype.

Six novel mutations were identified, representing 1.6% of the mutated alleles. Although no functional analysis was performed for these novel mutations, IVS8 + 1G>A, IVS9-1G>A, p.Gln262fs, and p.Gly424fs would be expected to lead to almost no residual enzymatic activity. IVS8 + 1G>A abolishes the intron 8 donor splice, leading to retention of intron 8 with the creation of a premature termination codon (44). IVS9-1G>A abolishes the acceptor site for intron 9, which would lead to a partial or complete deletion of exon 10, removing the critical region implicated in redox partner interaction and important residues for protein stability (44,45). p.Gln262fs introduces a premature termination codon 100 bp downstream, which would prevent functional protein expression. p.Gly424fs introduces a frame shift in exon 10, bringing the critical amino acids p.R426 and p.R435 in the heme binding a-helix as well as the stop codon out of frame (45).

The p.R408H mutation was not previously reported. However, p.R408C was found in two Brazilian patients (46), and an in vitro assay resulted in almost abolished enzymatic activity (47). In our study, p.R408H associated with IVS2-13A/C>G led to the SV form. Lastly, the p.R426P mutation would be expected to result in a classic phenotype. This location is a highly conserved pocket motif (34,44,45,49). p.R426H (49) and p.R426C (34) have been previously described in SV patients and were estimated to have less than 0.6% of normal activity. Our patient was compound heterozygous for p.R426P/p.V281L and had NC CAH.

We found CYP21A2 duplications in 2.7% of probands and 2.6% of parents. Koppens et al. (8) reported CYP21A2 duplications in six of 365 chromosomes studied in a combined cohort of CAH patients and unaffected controls. Loidi et al. (33) found that 7% of individuals in a random sample of a Spanish population carried at least one chromosome with duplicated CYP21A2. Because duplication of the active gene would confer protection from developing CAH in the event of a de novo pathogenic mutation arising in one of the copies, one would expect that duplications would be more common in the general population compared with the disease cohort. Interestingly, in our study, three of five unrelated probands with a CYP21A2 duplication had the same haplotype, although we cannot determine whether there is identity by descent present without sequencing of the complete gene. Kleinle et al. (37) recently described the same rare human leukocyte antigen haplotype in the majority of unaffected individuals carrying a CYP21A2 duplicated haplotype with p.Q318X. We also observed the association of p.Q318X with CYP21A2 duplications. Laboratories performing CYP21A2 analysis need to be cognizant of duplicated haplotypes, which may lead to inconclusive or misleading results.

In our cohort, de novo mutations were found in 0.9% of the informative alleles, which is in agreement with prior reports that suggest CYP21A2 de novo germline mutations account for 1–2% of CAH alleles (50). The presence of parental haplotypes with variable lengths of the RCCX module might predispose offspring to CYP21A2 de novo mutations. Meiotic unequal crossing over between bimodular and monomodular (51) and bimodular and trimodular RCCX units (52) has been implicated as a possible cause of de novo mutations in offspring. The mother of our patient with a de novo deletion had a monomodular chromosome with deletion of CYP21A1P. Our other de novo mutation was a point mutation (p.I172N) and parental haplotypes were bimodular.

Lastly, we previously reported UPD of chromosome 6 as cause of CAH (38). Prevalence of UPD as a cause of CAH is unknown because CAH is usually diagnosed clinically, and genetic evaluation of families is not always performed. We found this to be a rare occurrence.

CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency is one of the most common autosomal recessive diseases, but the genetic diagnosis is among the most complicated of all monogenic disorders. Our study is a description of the complexities encountered when genotyping patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency and provides the prevalence data of these complexities in a large cohort. CYP21A2 analysis is commonly used in clinical practice in the United States. The high variability of the CYP21A2 locus results in complex genetic variation, including the continual identification of rare previously undescribed mutations, and the presence of unusual haplotypes, which could result in erroneous assignment of carrier or disease status and might predispose offspring to de novo mutations. We recommend that sequencing be performed in all patients with clinical and hormonal evidence of 21-hydroxylase and undetermined genotype and in patients with discordant genotype-phenotype. The widely used molecular diagnostics of CYP21A2 mutations could be improved by using a combination of strategies, such as PCR-based detection methods, sequencing, and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (53), a method for analyzing deletions and duplications within the CYP21A2 gene. Evaluation of the RCCX region may also be needed in select cases. Clinicians and genetic counselors should be aware that genetic analysis beyond targeted CYP21A2 mutational detection is indicated in a subset of CAH patients, and sometimes in unaffected carriers, to provide appropriate anticipatory guidance and genetic counseling.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients for their participation in this study. We are grateful to Dana E. Weber for his excellent technical support. We also want to thank the National Institute of Aging Core Laboratory staff for DNA extraction and sample processing and Ms. Tina Roberson for administrative assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Aging, and the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and (in part) by the Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Research, Education and Support Foundation. D.P.M. is a Commissioned Officer in the United States Public Health Service.

Disclosure Summary: G.P.F., W.C., S.P.M., R.M.H., C.V.R., and N.B.M. have nothing to declare. F.K.F. is an employee of Esoterix, Inc., which performs clinical testing for CAH. D.P.M. received research funding from Phoqus Pharmaceuticals during 2007–2008.

First Published Online October 6, 2010

Abbreviations: C4, Complement; CAH, congenital adrenal hyperplasia; NC, nonclassic; RCCX, RP-C4-CYP21-TNX; RP, serine threonine nuclear protein kinase; SV, simple virilizing; SW, salt-wasting; TNX, tenascin; UPD, uniparental disomy.

References

- Merke DP, Bornstein SR 2005 Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Lancet 365:2125–2136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therrell Jr BL, Berenbaum SA, Manter-Kapanke V, Simmank J, Korman K, Prentice L, Gonzalez J, Gunn S 1998 Results of screening 1.9 million Texas newborns for 21-hydroxylase-deficient congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Pediatrics 101:583–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kamp HJ, Wit JM 2004 Neonatal screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Eur J Endocrinol 151(Suppl 3):U71–U75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitness J, Dixit N, Webster D, Torresani T, Pergolizzi R, Speiser PW, Day DJ 1999 Genotyping of CYP21, linked chromosome 6p markers, and a sex-specific gene in neonatal screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:960–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speiser PW, Dupont B, Rubinstein P, Piazza A, Kastelan A, New MI 1985 High frequency of nonclassical steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet 37:650–667 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena K, Kitzmiller KJ, Wu YL, Zhou B, Esack N, Hiremath L, Chung EK, Yang Y, Yu CY 2009 Great genotypic and phenotypic diversities associated with copy-number variations of complement C4 and RP-C4-CYP21-TNX (RCCX) modules: a comparison of Asian-Indian and European American populations. Mol Immunol 46:1289–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parajes S, Quinteiro C, Domínguez F, Loidi L 2008 High frequency of copy number variations and sequence variants at CYP21A2 locus: implication for the genetic diagnosis of 21-hydroxylase deficiency. PLoS ONE 3:e2138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppens PF, Hoogenboezem T, Degenhart HJ 2002 Duplication of the CYP21A2 gene complicates mutation analysis of steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: characteristics of three unusual haplotypes. Hum Genet 111:405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedell A, Stengler B, Luthman H 1994 Characterization of mutations on the rare duplicated C4/CYP21 haplotype in steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Hum Genet 94:50–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchong CA, Zhou B, Rupert KL, Chung EK, Jones KN, Sotos JF, Zipf WB, Rennebohm RM, Yung Yu C 2000 Deficiencies of human complement component C4A and C4B and heterozygosity in length variants of RP-C4-CYP21-TNX (RCCX) modules in Caucasians. The load of RCCX genetic diversity on major histocompatibility complex-associated disease. J Exp Med 191:2183–2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppens PF, Hoogenboezem T, Degenhart HJ 2002 Carriership of a defective tenascin-X gene in steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency patients: TNXB-TNXA hybrids in apparent large-scale gene conversions. Hum Mol Genet 11:2581–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PC, Vitek A, Dupont B, New MI 1988 Characterization of frequent deletions causing steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:4436–4440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone N, Braun A, Roscher AA, Knorr D, Schwarz HP 2000 Predicting phenotype in steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency? Comprehensive genotyping in 155 unrelated, well defined patients from southern Germany. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:1059–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stikkelbroeck NM, Hoefsloot LH, de Wijs IJ, Otten BJ, Hermus AR, Sistermans EA 2003 CYP21 gene mutation analysis in 198 patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency in The Netherlands: six novel mutations and a specific cluster of four mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:3852–3859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jääskelainen J, Levo A, Voutilainen R, Partanen J 1997 Population-wide evaluation of disease manifestation in relation to molecular genotype in steroid 21-hydroxylase (CYP21) deficiency: good correlation in a well defined population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:3293–3297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speiser PW, Dupont J, Zhu D, Serrat J, Buegeleisen M, Tusie-Luna MT, Lesser M, New MI, White PC 1992 Disease expression and molecular genotype in congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Invest 90:584–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone N, Braun A, Weinert S, Peter M, Roscher AA, Partsch CJ, Sippell WG 2002 Multiplex minisequencing of the 21-hydroxylase gene as a rapid strategy to confirm congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Clin Chem 48:818–825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day DJ, Speiser PW, White PC, Barany F 1995 Detection of steroid 21-hydroxylase alleles using gene-specific PCR and a multiplexed ligation detection reaction. Genomics 29:152–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Wu YL, Yang Y, Zhou B, Yu CY 2005 Human complement components C4A and C4B genetic diversities: complex genotypes and phenotypes. Curr Protoc Immunol Chap 13:Unit 13.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HH, Lee YJ, Lin CY 2004 PCR-based detection of the CYP21 deletion and TNXA/TNXB hybrid in the RCCX module. Genomics 83:944–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parajes S, Quinterio C, Domínguez F, Loidi L 2007 A simple and robust quantitative PCR assay to determine CYP21A2 gene dose in the diagnosis of 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Clin Chem 53:1577–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YL, Savelli SL, Yang Y, Zhou B, Rovin BH, Birmingham DJ, Nagaraja HN, Hebert LA, Yu CY 2007 Sensitive and specific real-time polymerase chain reaction assays to accurately determine copy number variations (CNVs) of human complement C4A, C4B, C4-long, C4-short, and RCCX modules: elucidation of C4 CNVs in 50 consanguineous subjects with defined HLA genotypes. J Immunol 179:3012–3025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedell A, Thilén A, Ritzén EM, Stengler B, Luthman H 1994 Mutational spectrum of the steroid 21-hydroxylase gene in Sweden: implications for genetic diagnosis and association with disease manifestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:1145–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi Y, Hiromasa T, Tanae A, Miki T, Nakura J, Kondo T, Ohura T, Ogawa E, Nakayama K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y 1991 Effects of individual mutations in the P-450(C21) pseudogene on the P-450(C21) activity and their distribution in the patient genomes of congenital steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Biochem 109:638–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone N, Riepe FG, Grötzinger J, Partsch CJ, Sippell WG 2005 Functional characterization of two novel point mutations in the CYP21 gene causing simple virilizing forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speiser PW, New MI 1987 Genotype and hormonal phenotype in nonclassical 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 64:86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armengaud JB, Charkaluk ML, Trivin C, Tardy V, Bréart G, Brauner R, Chalumeau M 2009 Precocious pubarche: distinguishing late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia from premature adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:2835–2840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Witchel SF, Dobrowolski SF, Moulder PV, Jarvik JW, Telmer CA 2004 Detection and assignment of CYP21 mutations using peptide mass signature genotyping. Mol Genet Metab 82:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedell A, Luthman H 1993 Steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: two additional mutations in salt-wasting disease and rapid screening of disease-causing mutations. Hum Mol Genet 2:499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedell A, Ritzén EM, Haglund-Stengler B, Luthman H 1992 Steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: three additional mutated alleles and establishment of phenotype-genotype relationships of common mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:7232–7236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro M, Lajic S, Baldazzi L, Balsamo A, Pirazzoli P, Cicognani A, Wedell A, Cacciari E 2004 Functional analysis of two recurrent amino acid substitutions in the CYP21 gene from Italian patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2402–2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone N, Riepe FG, Partsch CJ, Vorhoff W, Brämswig J, Sippell WG 2006 Three novel point mutations of the CYP21 gene detected in classical forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 114:111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loidi L, Quinteiro C, Parajes S, Barreiro J, Leston DG, Cabezas-Agricola JM, Sueiro AM, Araujo-Vilar D, Catro-Feijoo L, Costas J, Pombo M, Dominguez F 2006 High variability in CYP21A2 mutated alleles in Spanish 21-hydroxylase deficiency patients, six novel mutations and a founder effect. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 64:330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grischuk Y, Rubtsov P, Riepe FG, Grötzinger J, Beljelarskaia S, Prassolov V, Kalintchenko N, Semitcheva T, Peterkova V, Tiulpakov A, Sippell WG, Krone N 2006 Four novel missense mutations in the CYP21A2 gene detected in Russian patients suffering from the classical form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia: identification, functional characterization, and structural analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4976–4980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedell A, Luthman H 1993 Steroid 21-hydroxylase (P450c21): a new allele and spread of mutations through the pseudogene. Hum Genet 91:236–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoshkov A, Lajic S, Vlamis-Gardikas A, Tranebjaerg L, Holst M, Wedell A, Luthman H 1998 Naturally occurring mutants of human steroid 21-hydroxylase (P450c21) pinpoint residues important for enzyme activity and stability. J Biol Chem 273:6163–6165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinle S, Lang R, Fischer GF, Vierhapper H, Waldhauser F, Födinger M, Baumgartner-Parzer SM 2009 Duplications of the functional CYP21A2 gene are primarily restricted to Q318X alleles: evidence for a founder effect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3954–3958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker EA, Hovanes K, Germak J, Porter F, Merke DP 2006 Maternal 21-hydroxylase deficiency and uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 6 and X results in a child with 21-hydroxylase deficiency and Klinefelter syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 140:2236–2240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes LG, Huang N, Agrawal V, Mendonça BB, Bachega TA, Miller WL 2009 Extraadrenal 21-hydroxylation by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4: effect on 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:89–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RC, Mercado AB, Cheng KC, New MI 1995 Steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: genotype may not predict phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:2322–2329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L'Allemand D, Tardy V, Grüters A, Schnabel D, Krude H, Morel Y 2000 How a patient homozygous for a 30-kb deletion of the C4-CYP 21 genomic region can have a nonclassic form of 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:4562–4567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo RS, Mendonca BB, Barbosa AS, Lin CJ, Marcondes JA, Billerbeck AE, Bachega TA 2007 Microconversion between CYP21A2 and CYP21A1P promoter regions causes the nonclassical form of 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:4028–4034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobba A, Marra E, Lattanzio P, Iolascon A, Giannattasio S 2000 Characterization of the CYP21 gene 5′ flanking region in patients affected by 21-OH deficiency. Hum Mutat 15:481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan RI, Getoor L, Wilbur WJ, Mount SM 2007 SplicePort—an interactive splice-site analysis tool. Nucleic Acids Res 35:W285–W291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins T, Carlsson J, Sunnerhagen M, Wedell A, Persson B 2006 Molecular model of human CYP21 based on mammalian CYP2C5: structural features correlate with clinical severity of mutations causing congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Mol Endocrinol 20:2946–2964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billerbeck AE, Mendonca BB, Pinto EM, Madureira G, Arnhold IJ, Bachega TA 2002 Three novel mutations in CYP21 gene in Brazilian patients with the classical form of 21-hydroxylase deficiency due to a founder effect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:4314–4317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soardi FC, Barbaro M, Lau IF, Lemos-Marini SH, Baptista MT, Guerra-Junior G, Wedell A, Lajic S, de Mello MP 2008 Inhibition of CYP21A2 enzyme activity caused by novel missense mutations identified in Brazilian and Scandinavian patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:2416–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner-Parzer SM, Schulze E, Waldhäusl W, Pauschenwein S, Rondot S, Nowotny P, Meyer K, Frisch H, Waldhauser F, Vierhapper H 2001 Mutational spectrum of the steroid 21-hydroxylase gene in Austria: identification of a novel missense mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:4771–4775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro M, Baldazzi L, Balsamo A, Lajic S, Robins T, Barp L, Pirazzoli P, Cacciari E, Cicognani A, Wedell A 2006 Functional studies of two novel and two rare mutations in the 21-hydroxylase gene. J Mol Med 84:521–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speiser PW, White PC 2003 Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. N Engl J Med 349:776–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott P, Collier S, Costigan C, Dyer PA, Harris R, Strachan T 1990 Genesis by meiotic unequal crossover of a de novo deletion that contributes to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:2107–2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner-Parzer SM, Fischer G, Vierhapper H 2007 Predisposition for de novo gene aberrations in the offspring of mothers with a duplicated CYP21A2 gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:1164–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concolino P, Mello E, Toscano V, Ameglio F, Zuppi C, Capoluongo E 2009 Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) assay for the detection of CYP21A2 gene deletions/duplications in congenital adrenal hyperplasia: first technical report. Clin Chim Acta 402:164–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Kim MS, Shanbhag S, Arai A, VanRyzin C, McDonnell NB, Merke DP 2009 The phenotypic spectrum of contiguous deletion of CYP21A2 and tenascin XB: quadricuspid aortic valve and other midline defects. Am J Med Genet A 149A:2803–2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]