Abstract

Alkoxyamines react with the open-chain aldehyde form of AP-sites in DNA to produce open-chain aldehyde oximes. Here we characterize the effect of AP-site cleavage by yeast AP-endonuclease 1 (APN1) or T4 pyrimidine dimer DNA glycosylase/AP-lyase (T4 Pdg) on the efficiency and stability of the alkoxyamine aldehyde reactive probe (ARP) condensation reaction with AP-sites. The results indicate that (1) reaction of ARP with the open-chain aldehyde equilibrium form of the AP-site was less efficient than with the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde produced by T4 Pdg; (2) the dRP moiety was least reactive with ARP; (3) both the AP-site and 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde were stable with regard to reaction with ARP over a 30-min incubation period at 37°C; and (4) ARP adducted to the open-chain aldehyde form of the AP-site could be replaced by methoxyamine, but the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde ARP oxime was stable against methoxyamine attack.

Keywords: AP-site, Aldehyde reactive probe, AP-lyase, AP-endonuclease, Uracil-DNA glycosylase, Oxime

INTRODUCTION

Abasic or apurinic/apyrimidinic sites (AP-sites) in DNA are one of the most common forms of DNA damage.[1] AP-sites arise from spontaneous base hydrolysis as well as from modification of bases by DNA-damaging agents such as bleomycin,[2] alkylating agents,[3,4] ionizing radiation,[5] and free radicals[6] that destabilize the N-glycosylic bond linking the DNA base to deoxyribose. AP-sites also result from the actions of DNA glycosylases and are toxic intermediates in the base excision DNA repair pathway. AP-sites have been estimated to occur at a rate of 10,000[7] to 50,000[8] per cell per day. AP-sites inhibit DNA replication,[9] cause stalling of transcription,[10] and promote loss of genetic integrity.[11]

The AP-site is not a chemically unique species but exists as an equilibrium mixture of the ring-closed cyclic hemiacetals and open-chain aldehyde and hydrate forms.[12,13] The transient open-chain aldehyde form is reactive with aldehyde-specific reagents such as hydroxylamine,[14] methoxyamine,[15] and O-(4-nitrobenzyl)hydroxylamine.[16] Aldehyde reactive probe or ARP (N′-aminoxymethylcarbonylhydrazino d-biotin) was first synthesized by Kubo et al.[17] Like other alkoxyamines, it reacts with aldehydes in a condensation reaction to form an oxime.[17] ARP has been used to quantify AP-sites in genomic DNA in Elisa[18] and slot blot assays.[19] In this report, we examine the ARP-AP-site condensation reaction and characterize the effect of AP-lyase-mediated cleavage of the AP-site on the efficiency and stability of ARP adduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Oligonucleotides U-24-mer (5′-GATGACGCACGTAUAAGTGATGAC-3′) and its complement A-24-mer (5′-GTCATCACTTATACGTGCGTCATC-3′) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). N′-aminoxymethylcarbonylhydrazino d-biotin (Aldehyde Reactive Probe) was purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD), resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 as a 20-mM stock solution, and stored at 4°C. Methoxyamine was purchased from Sigma, resuspended in 10 mM Tris pH 7.5 as a 1.5-M solution, and stored at −80°C. The vector pGST-APN1 was obtained from Dr. D. Ramotar (Universite de Montreal), and pRSET-8k, encoding amino acids 1–87 of the N-terminal 8-kDa domain of DNA polymerase β, was provided Dr. S.H. Wilson (NIEHS). Purified bacteriophage T4 pyrimidine-DNA glycosylase (T4pdg) was obtained from Dr. R. S. Lloyd (Oregon Health Sciences University).

DNA Substrate Preparation

Oligonucleotide U-24-mer was 5′-end 32P-labeled in a reaction containing [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase, annealed to 5′-end phosphorylated oligonucleotide A-24-mer at a 1:1.5 molar ratio, and purified as previously described.[20] Terminal transferase and [α-32P]Cordycepin 5′-triphosphate were used according to the manufacturer’s directions (Fermentas, Hanover,MD) to 3′-end 32P label the U-24-mer oligonucleotide. The resulting 32P U-25-mer was annealed to A-24-mer and purified as described above.

Protein Purification

Escherichia coli uracil-DNA glycosylase (fraction V) was purified as previously described by Bennett et al.[20] Saceharomyces cerevisiae apurinic endonuclease I (APN1) and the 8-kDa domain of rat DNA polymerase β were purified using published protocols.

Uracil-DNA Glycosylase Reactions

Reactions (10 µl) to detect uracil and AP-site-metabolizing enzyme activities contained 2 pmol of 32P U·A DNA and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, and 0.02% NP-40. Following incubation at 37°C for 30 min, reactions were stopped on ice by the addition of an equal volume of formamide sample dye and stored at −80°C. ARP and/or methoxyamine (MX) were added as indicated in the figure legends. In reactions containing 3′-end 32P-labeled DNA, the 5′-dRP moiety was reduced by the addition of 1.76 µl of 2 M NaBH4 in ice-cold dH2O (pH 11.5) and incubation on ice for 30 min. The reactions were then neutralized with 1.3 µl of 1 M HCl, incubated on ice 10 min, supplemented with 7 µl of ice-cold 150 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 20 µl of formamide sample dye. Reaction samples were heated at 90°C for 2 min prior to resolution by 20% denaturing polyacrylamide electrophoresis. Following electrophoresis, gels were wrapped in plastic wrap, cooled to 4°C, and subjected to autoradiography at 4°C.

RESULTS

Detection of Uracil Excision and AP Site Incision Activities

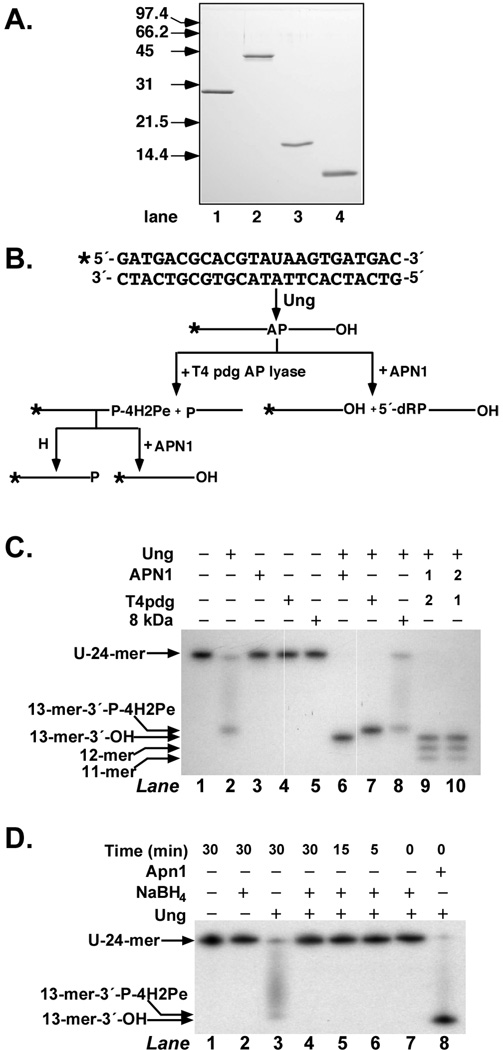

Prior to detection of the uracil and AP-site-metabolizing activities of Ung, APN1, T4pdg, and the 8-kDa protein, each protein was purified to apparent homogeneity as described in Materials and Methods. A sample of each preparation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and the results are shown in Figure 1A. Each protein preparation was judged to be >95% pure by Coomassie Blue staining. A flowchart of the anticipated enzymatic digestion products of 32P U·A-24-mer DNA is shown in Figure 1B. The reaction sequence is initiated by Ung, which excises the uracil base at position 14 of double-stranded DNA substrate to create an AP-site. If the AP-site is reacted with an AP endonuclease such as APN1, it is cleaved on the 5′-side of the baseless deoxyribose to yield a 3′-OH and a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) moiety. However, if the AP-site is reacted with an AP lyase such as T4pdg, it is cleaved on the 3′-side to yield a 3′-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal-5-phosphate group (P-4H2Pe) and a 5′-phosphate (P). To verify that the purified protein fractions were free of contaminating activities, each preparation was reacted separately with the 32P U·A-24-mer DNA substrate as described under Materials and Methods and the results are shown in Figure 1C. Inspection of the autoradiograph, lanes 1–5, attests to the absence of nuclease activity in either the DNA substrate preparation or the purified protein fractions. Following the reaction of Ung with the 32P U·A-24-mer (Figure 1C, lane 2), a portion of the AP-site–containing DNA product underwent β-elimination (see Figure 1D) during sample preparation and denaturing gel electrophoresis to yield a 32P 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe oligonucleotide and, not visible, a 5′-P-10-mer. When the 32P U·A-24-mer DNA substrate was reacted with Ung and APN1, all of the substrate was, as expected, converted to 32P-13-mer-3′-OH (Figure 1C, lane 6). Similarly, when the 32P U·A-24-mer DNA was reacted with Ung and T4pdg, all of the substrate was converted to 32P 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe (Figure 1C, lane 7). The electrophoretic mobility of the 32P 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe reaction product was slightly slower than that of 32P-13-mer-3′-OH, although the former contained an additional phosphate group. Reaction of the DNA substrate with UNG and the 8-kDa domain of DNA polymerase β, a 5′-dRPase, did not alter the mobility of the expected Ung 32P-labeled reaction product ((Figure 1C, lane 8), nor did the order of addition of APN1 and T4pdg to the incision reaction alter the expected product, 32P-13-mer-3′-OH. Since APN1 possesses a 3′-diesterase activity,[21] it cleaved the 3′-P-4H2Pe reaction product created by T4pdg to leave a 3′-OH; however, a 3′-OH is not substrate for T4pdg. The weak exonuclease activity of APN1 at the incised AP-site (D. Ramotar, personal communication) can be noted in Figure 1C, lanes 9 and 10. These results provided additional support regarding the purity of the Ung, APN1, T4pdg, and 8-kDa domain preparations and demonstrated that the actual reaction products detected were consistent with the predicted reaction products. Lastly, in Figure 1D, treatment of the Ung reaction product, 32P AP-site 24-mer, with 300 mM NaBH4 (lanes 4–7) stabilized the AP-site DNA, as expected, and abolished the streaking and 32P 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe band caused by heat-catalyzed β-elimination that occurs during sample heating and denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the absence of NaBH4 addition (lane 3). The time course of NaBH4 addition showed that formation of a 32P 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe band did not occur at any time during the Ung incubation, indicating that the 32P AP-site·A-24-mer was stabile during the reaction time period. Excision of uracil by Ung occurred rapidly, since APN1-mediated cleavage of the Ung-treated 32P 24-mer DNA substrate produced 32P 13-mer-3′-OH at the earliest time point (lane 8).

FIGURE 1.

Detection of uracil and AP-site–metabolizing enzyme activities. (A) E. coli Ung, S. cerevisiae APN1, T4pdg, and human 8 kDa domain proteins were purified as described in Materials and Methods. Samples (1 µg) were analyzed by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized following staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Arrows indicate the mobility of SDS-PAGE low-range molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad). (B) The double-stranded 5′-end 32P-labeled oligonucleotide substrate was constructed as described in Materials and Methods and contained a site-specific uracil residue at position 14 of the 32P-labeled strand. The flowchart depicts the 32P-labeled DNA fragments generated by the successive actions of uracil-DNA glycosylase, T4pdg AP lyase, APN1, and heat. (C) Reactions (20 µl) contained 2 pmol of [32P] U·A-24-mer DNA and various combinations of Ung (0.2 units), Apn1 (0.2 pmol), T4pdg (0.2 pmol), or 8 kDa domain (1 pmol) as indicated, and were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Reactions were stopped with formamide sample buffer and subjected to 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows indicate the mobility of the [32P]oligonucleotides. The numbers 1 and 2 above lanes 9 and 10 refer to the order of addition of APN1 and T4pdg. (D) Reactions (10 µl) contained 2 pmol of [32P] U·A-24-mer DNA and 0.2 units of Ung and 0.2 pmol of APN1 as indicated. The reactions were incubated for 0–30 min, stopped on ice at the times indicated with freshly prepared NaBH4, and analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography as described in Materials and Methods.

Reaction of ARP with AP Site DNA

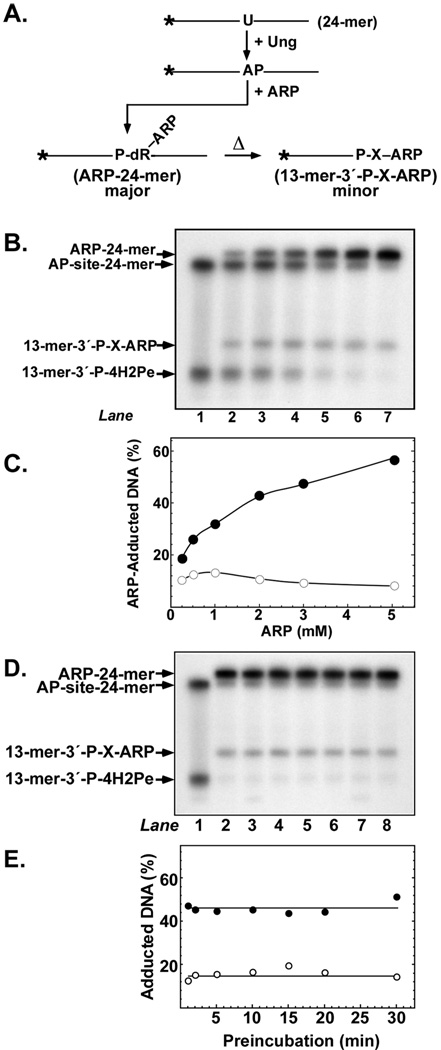

ARP can react with the open-chain aldehyde form of the AP-site, adducting a biotin moiety to the DNA via the relatively stabile oxime linkage.[18] As illustrated in Figure 2A, ARP adducts the open-chain aldehyde leaving the phosphodiester chain intact to generate ARP-24-mer. Subsequent heating during sample preparation and denaturing gel electrophoresis of ARP-24-mer may promote a small degree of 3′-strand breakage to yield 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP (Figure 2A). Alternatively, a minor amount of ARP-24-mer may degrade to 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP during the 37°C incubation. In order to characterize the reaction of ARP with a freshly created AP-site in double-stranded DNA, a uracil-containing oligonucleotide, U-24-mer, was 5′-end 32P-labeled and annealed to its A-containing complement. The resulting 32P U·A-24-mer DNA substrate was reacted with E. coli uracil-DNA glycosylase (Ung) to create an AP-site, and the reaction mixtures were titrated with increasing concentrations of ARP (0–5 mM); subsequently, the reaction products were resolved by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography (Figure 2B). Adduction to ARP retards the electrophoretic mobility of the DNA, allowing for ready identification of the adducted species by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Examination of the autoradiograph in Figure 2B shows the mobility of AP-site 24-mer, ARP-24-mer, 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP, and the 13-mer-3′-P-X-4H2Pe moiety, which is produced from an unadducted AP-site 24-mer by sample heating and gel electrophoresis (see Figure 1D). The amount of ARP-24-mer formed during the 60-min reaction period increased as the concentration of the ARP reagent increased (Figure 2B, lanes 2–7). Densitometric quantification of the autoradiograph revealed a hyperbolic dependence of ARP-24-mer formation on ARP concentration (Figure 2C). At 3 mM ARP, 48% of the 32P 24-mer was detected in the mobility-shifted ARP-24-mer band. Degradation of ARP-24-mer to the smaller 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP adduct remained more or less constant regardless of ARP concentration, representing 8–12% of the radiolabeled DNA. Next, the stability of the freshly produced AP-site was investigated by extending the pre-incubation with Ung from 1 to 30 min prior to adding 5 mM ARP (Figure 2D). The amount of Ung (0.2 units) in the reaction was sufficient to excise the uracil residues in 10 pmol of 32P U·A-24-mer DNA in less than 1 min (Figure 1D). The extent of ARP adduction to AP-site 24-mer was about the same (48%) regardless of the pre-incubation time period, as was the amount of 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP formed (12–16%) (Figure 2E). Thus, the AP-site remained reactive toward ARP for at least 30 min at 37°C.

FIGURE 2.

Reaction of ARP with AP-site DNA. (A) Scheme depicting ARP adduction to an AP-site created by Ung-mediated excision of a uracil residue. (B) Reactions containing 10 pmol of 32P U·A-24-mer DNA, 0.2 units of Ung, and 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, or 5 mM ARP (lanes 1–7, respectively) were incubated at 37°C for 60 min, stopped on ice by the addition of formamide sample buffer, and analyzed by 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography as described in the legend to Figure 1. Arrows indicate the mobility of the 32P oligonucleotides. (C) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram shown in (B). Filled circles represent 32P ARP-24-mer, open circles 32P 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP. (D) Effect of preincubation time on AP-site reactivity with ARP. Reactions contained 10 pmol of 32P U·A-24-mer DNA, and 0.2 units of Ung were added 30, 20, 15, 10, 5, 2, or 1 min (lanes 2–8) prior to the addition of 5 mM ARP for 30 min. ARP was not added to the reaction shown in lane 1. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as outlined in the legend to Figure 1. (E) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram presented in (D). Filled circles represent 32P ARP-24-mer, open circles 32P 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP. ARP-adducted 32P DNA is expressed as a percentage of total 32P DNA detected.

Reaction of ARP with T4pdg-Incised AP Site DNA

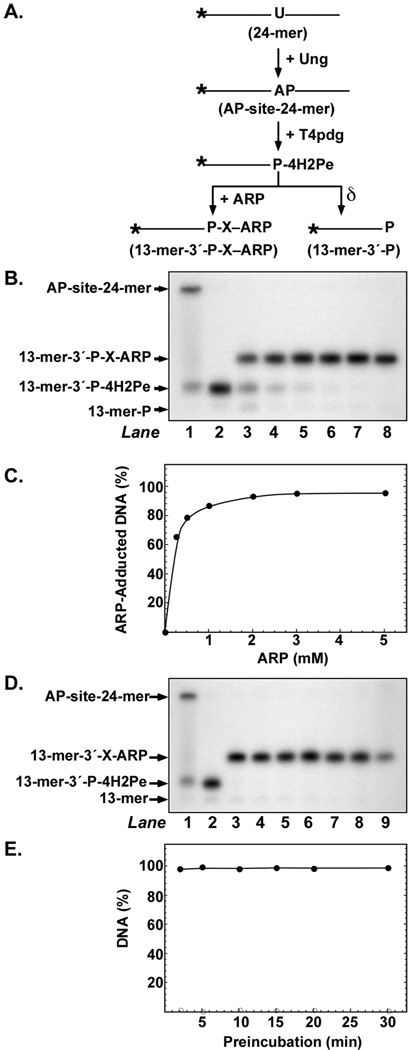

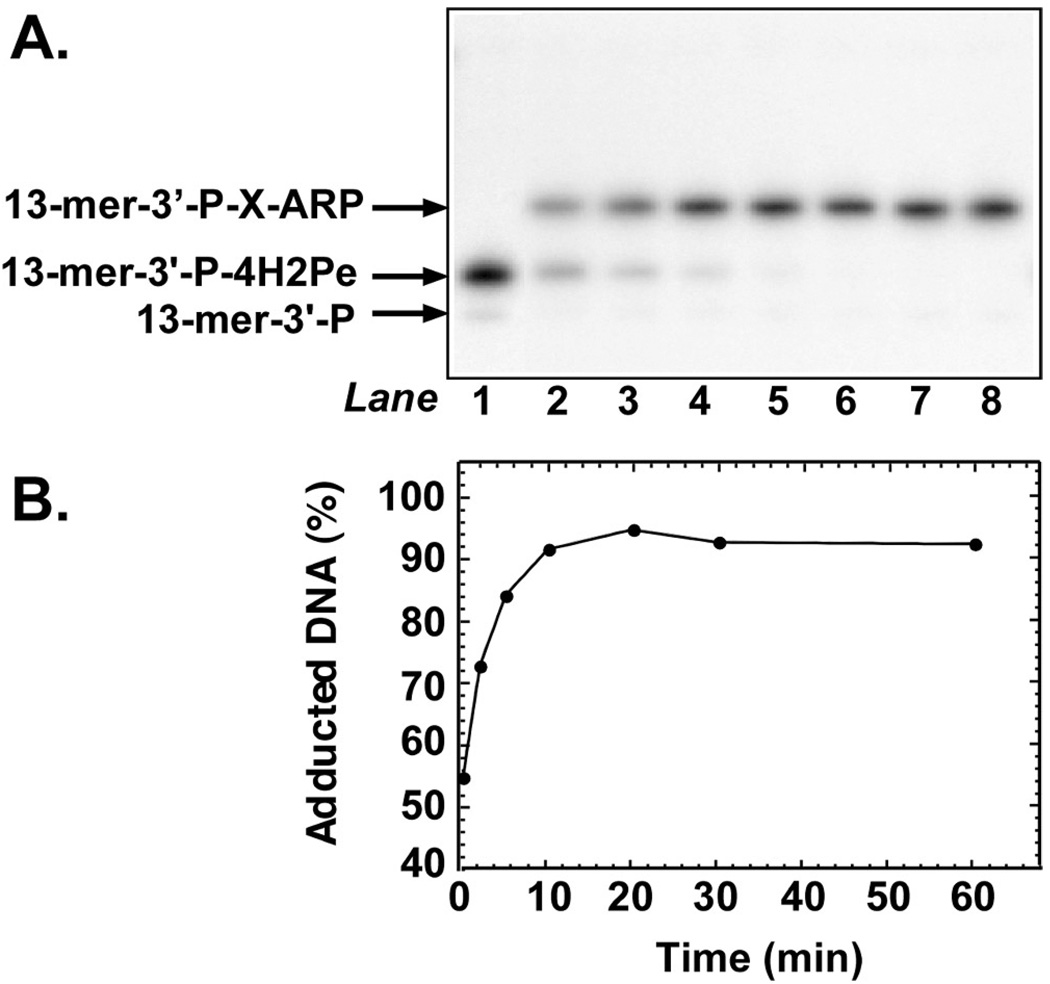

The reaction of ARP with AP-site 24-mer DNA shown in Figure 2B revealed that the electrophoretic mobility of the 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP product was retarded relative to the mobility of 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe, the β-elimination product created by heating during analysis. These results suggested that more slowly migrating form was 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP, where X stands for the 4-hydroxy-2-pentenimine moiety of the oxime. In order to investigate the reactivity of the 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe β-elimination product toward ARP, the 32P U·A-24-mer DNA substrate was co-incubated with Ung and T4pdg, which possesses a robust AP-lyase activity. A scheme of the reaction course is presented in Figure 3A. When the Ung-mediated AP-site DNA was incubated with T4pdg, the 24-mer DNA substrate was cleaved to produce 32P 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe (Figure 3B, lane 2). Inclusion of ARP (0.25–5 mM) in the reaction resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in the amount of ARP-adducted 13-mer produced (Figure 3B, lanes 3–8). Quantification of the autoradiograph revealed that the extent of ARP adduction displayed a hyperbolic dependence on ARP concentration that saturated at about 2 mM, and that >95% of the 32P-labeled DNA was adducted at saturation. Thus, the T4pdg-cleaved AP-site 24-mer DNA was more reactive toward ARP than the intact AP-site DNA. At low ARP concentrations (0–0.5 mM), a small amount of δ-elimination product, 13-mer-P, was observed, which was most likely created by heating during sample preparation and denaturing gel electrophoresis, (Figure 3B, lanes 1 and 2, arrow). The stability of the T4pdg-produced 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe moiety was investigated as outlined above for AP-site 24-mer; that is, by extending the pre-incubation time with Ung from 1 to 30 min prior to adding ARP (Figure 3D). The results show that the 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe α,β-unsaturated aldehyde moiety was remarkably stable with respect to ARP adduction over the 30-min time period, and that the amount of adduct formed relative to total 32P DNA detected approached 100% (Figure 3E). To investigate the kinetics of ARP adduction to the T4pdg-incision product 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe, a time course experiment was conducted (Figure 4A). The results show that ARP adduction to the α,β-unsaturated moiety occurred quite rapidly, as over 50% of the 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe DNA was adducted in the time required to process the sample at the 0 min time point. By 10 min, the adduction reaction had plateaued at >96% adduct formation (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 3.

Reaction of ARP with T4pdg-incised AP-site DNA. (A) Scheme showing ARP adduction to the 3′-4H2Pe α,β-unsaturated aldehyde created by T4pdg incision of the Ung-mediated AP-site. (B) Reactions consisted of 10 pmol of 32P U·A-24-mer DNA, 0.2 units of Ung, 2 pmol of T4pdg, and 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, or 5 mM ARP (lanes 2–8, respectively). The control reaction shown in lane 1 did not contain T4pdg or ARP. The reaction conditions and subsequent analysis were the same as outlined in the legend to Figure 2B. (C) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram shown in (B). Filled circles represent [32P] 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP. (D) Effect of preincubation time on 3′-4H2Pe reactivity with ARP. Reactions contained 10 pmol of 32P U·A-24-mer DNA and 0.2 units of Ung, and 2 pmol of T4pdg was added 30, 20, 15, 10, 5, 2, or 1 min prior to the addition of 5 mM ARP for 30 min (lanes 3–9, respectively). Control reactions consisting of 32PU·A-24-mer DNA and Ung (lane 1), and 32PU·A-24-mer DNA, Ung, and T4pdg (lane 2), were conducted in the absence of ARP for 30 min at 37°C. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as outlined in the legend to Figure 1. (E) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram presented in (D). Filled circles represent 32P 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP. ARP-adducted 32P DNA is expressed as a percentage of total 32P DNA detected.

FIGURE 4.

Time dependence of ARP adduction to T4pdg-incised AP-site DNA. (A) An autoradiogram is shown of reactions containing 32P U·A-24-mer DNA (10 pmol), Ung (0.2 units), T4pdg (2 pmol), and ARP (5 mM). In a control reaction, ARP was omitted (lane 1). Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min (lanes 3–9, respectively), and analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as described in the legend to Figure 1. (B) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram presented in (A). Filled circles represent 32P 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP. ARP-adducted DNA is expressed as a percentage of total 32P DNA detected. Arrows indicate the mobility of the 32P oligonucleotides during electrophoresis.

Effect of APN1 on ARP Adduction

When APN1 was added to the ARP reaction prior to the addition of T4pdg, a mobility-shifted band associated with ARP adduction was not observed (data not shown). This result is consistent with the known cleavage specificity of APN1. APN1 cleaves 5′ to the AP-site to leave a 3′-OH, which does not react with ARP. When T4pdg was added to the ARP reaction followed by APN1 addition, the mobility-shifted 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP band was absent (data not shown). Since the ARP adduction reaction to 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe was observed to be rapid (Figure 4), the absence of a 13-mer-3′-PX-ARP band suggests that the 3′-diesterase activity of APN1 removed the 3′ ARP adduct.

Effect of Methoxyamine on ARP Adduction

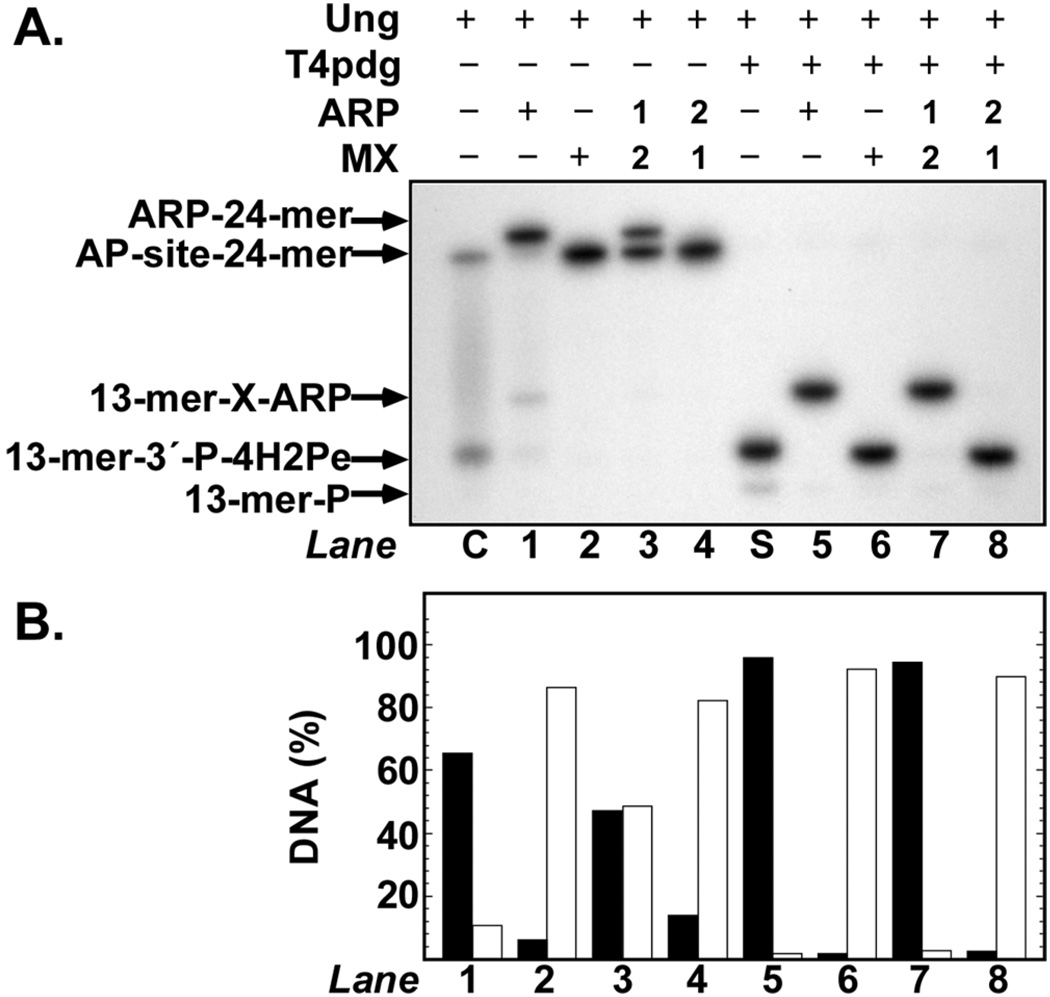

Methoxyamine (MX) is a small alkoxyamine that shares the same reactive group (NH2O-R) as ARP. To investigate the effect of MX on ARP adduction, a competition experiment was conducted (Figure 5). Control reactions show the positions of the AP-site 24-mer, ARP-24mer, 13-mer-3-P-4H2Pe, and 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP bands (Figure 5, lanes C, 1, S, and 5, respectively). When MX was added to AP-site 24-mer, no shift in the mobility of the AP-site 24-mer band was observed (Figure 5, lane 2). Similarly, addition of MX to 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe did not result in a noticeable band mobility shift (Figure 5, lane 6). Since MX is a small molecule (FW 47.06), adduction of MX to 24- or 13-mer DNA (MX-24-mer or 13-mer-3′-P-XMX) apparently did not affect the electrophoretic mobility of the DNAs. Talpaert-Borle and Liuzzi[15] observed that AP-sites in calf thymus could be readily tagged with 14C-MX. However, they determined that the DNA lost 14C radioactivity when reacted with unlabeled MX, indicating a replacement reaction had occurred. To determine whether ARP-adducted DNA would be subject to replacement by MX, AP-site 24-mer DNA was reacted with ARP (5 mM) for 30 min, then supplemented with MX (5 mM), and incubated for an additional 30-min period (Figure 5, lane 3). Quantification of the autoradiograph showed that one-half of the mobility-shifted ARP-24-mer band now migrated at the same position as MX-24-mer, suggesting that half of the ARP adduct was replaced by MX during the 30-min period. When AP-site 24-mer DNA was first incubated with MX (5 mM) for 30-min, and then supplemented with ARP (5 mM) for 30 min, no band other than MX-24-mer was observed. We interpret this result to signify that the larger ARP molecule was unable to replace MX-adducted to AP-site DNA. The same experiment was conducted with ARP and MX using 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe DNA; however, in this case, the results were significantly different (Figure 5, lanes 5–8). As observed previously (Figure 3), the electrophoretic mobility of the 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe band was characteristically shifted when reacted with ARP (Figure 5, lane 5); reaction with MX did not alter the relative mobility of the 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe band. When 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe DNA was first incubated with ARP for 30 min, followed by MX for 30 min, no change in the retarded mobility of the 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP band was observed (Figure 5, lane 7). This result indicated that MX could not replace ARP in the 4-hydroxy-2-pentenal oxime. Lastly, as was the case with AP-site 24-mer, reaction of 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe with MX followed by ARP did not result in replacement (Figure 5, lane 8).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of methoxyamine on ARP adduction to DNA. (A) An autoradiogram is shown of reactions that contained 32P U·A-24-mer DNA (10 pmol), Ung (0.2 unit), and ARP (5 mM), MX (5 mM), and T4pdg (2 pmol) as indicated; reactions were incubated at 37°C for 60min. In lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8, a 30-min incubation with either ARP or MX, labeled “1” for first addition, was followed by addition of either ARP or MX, labeled “2” for second addition and incubation for an additional 30-min period. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as described in the legend to Figure 1. (B) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram presented in (A). Solid bars indicate ARP-adducted 32P DNA, striped bars indicate 32P DNA not adducted to ARP; adducted and unadducted 32P DNA are expressed as a percentage of total 32P DNA detected.

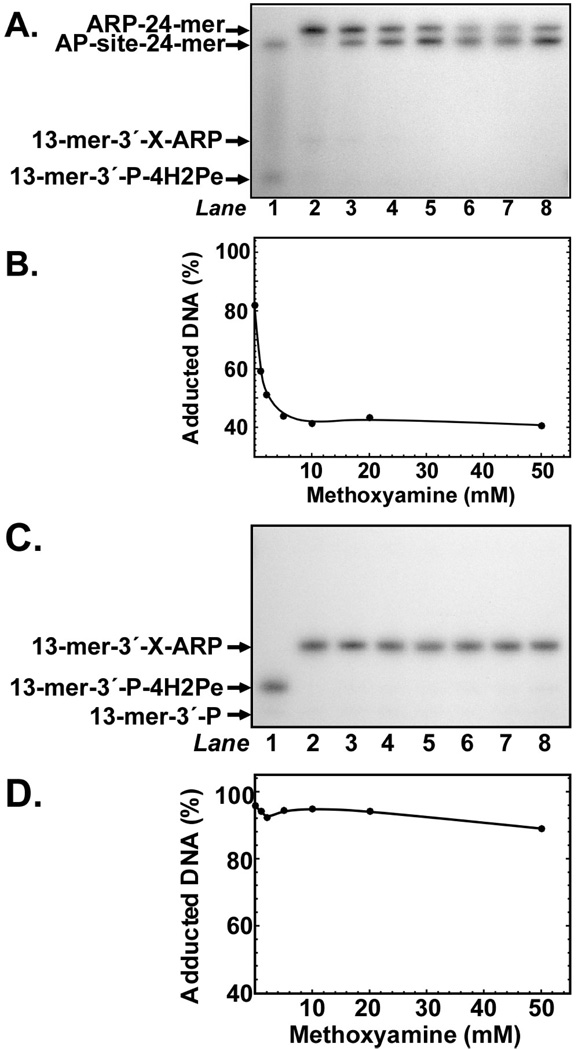

To determine the effect of MX concentration on the ARP-DNA replacement reaction, 32P U·A-24-mer was reacted for 30 min with Ung or Ung and T4pdg in the presence of ARP (5 mM) to generate ARP-24-mer and 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP, respectively, after which a concentration course of MX (1–50 mM) supplementation was conducted (Figure 6). For ARP-24-mer DNA, the results show a hyperbolic dependence of increasing MX concentration on loss of ARP-DNA adduct that saturated at 10 mM MX (Figures 6A and B). In contrast, for 13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP DNA, concentrations of MX as high as 50 mM did not measurably decrease the amount of ARP-adducted DNA. These results reinforce the observation that the 4-hydroxy-2-pentenal ARP oxime (13-mer-3′-P-X-ARP) was significantly more stable than the 2′-deoxy-d-erythropentofuranose open-chain aldehyde ARP oxime (ARP-24-mer).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of methoxyamine concentration on the ARP-DNA replacement reaction. (A) Autoradiogram of reactions that contained 32P U·A-24-mer (10 pmol), Ung (0.2 unit), and ARP (5 mM). Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, then 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, or 50 mM MX was added (lanes 3–8, respectively) and incubation continued for an additional 30-min period. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as described in the legend to Figure 3. Reactions in lanes 1 and 2 contained 32P U·A-24-mer and Ung, and 32P U·A-24-mer, Ung, and ARP, respectively. (B) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram shown in (A). ARP-adducted is expressed as a percentage of total 32P DNA detected. (C). Autoradiogram of reactions that contained 32PU·A-24-mer (10 pmol), Ung (0.2 unit), T4pdg (2 pmol), and ARP (5 mM). Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, then 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, or 50 mM MX was added (lanes 3–8, respectively) and incubation continued for an additional 30 min period. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as described in the legend to Figure 1. Reactions in lanes 1 and 2 contained 32P U·A-24-mer, Ung, and T4pdg, and 32P U·A-24-mer, Ung, T4pdg, and ARP, respectively. (D) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram shown in (C). ARP-adducted is expressed as a percentage of total 32P DNA detected.

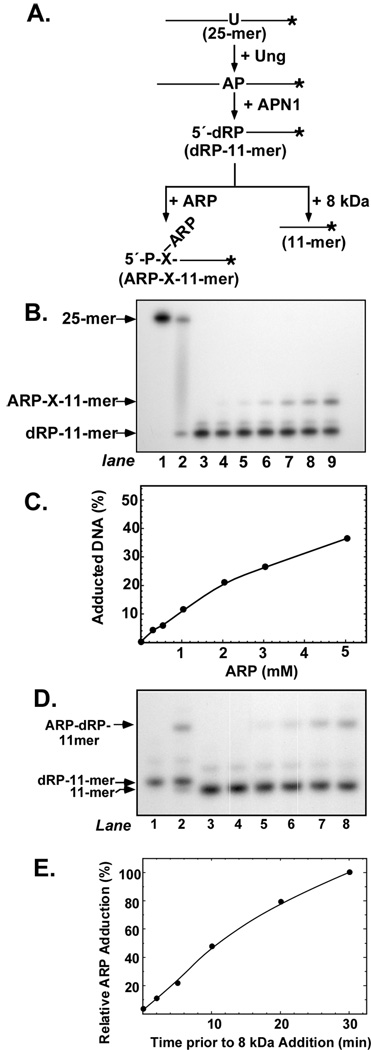

Reaction of ARP with 5′-dRP-DNA

In order to investigate the interaction of ARP with the 5′-end deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) moiety, the U-24-mer oligonucleotide was 3′-end 32P-labeled by the addition of [α-32P]Cordycepin and the 3′-end 32P-labeled U·A-25-mer DNA constructed as described under Material and Methods. If reacted with Ung and APN1, the double-stranded 32P-25-mer DNA substrate would release a 32P-labeled 11-mer with a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) moiety (Figure 7A). Loss of the 5′-dRP group through the action of the deoxyribophosphodiesterase (dRPase) activity associated with the DNA polymerase β 8-kDa domain or by heat would result in a 32P-labeled 11-mer with a 5′-phosphate terminus. To determine the relative activity of the purified 8-kDa domain protein preparation, the 32P dRP-11-mer (10 pmol) created by the actions of Ung and APN1 was titrated with 8-kDa protein (0.03–50 pmol) and the reaction products analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide electrophoresis (data not shown). Quantification of the results showed that virtually all the dRP moiety was removed by 0.4 or more pmol of 8-kDa protein. Care was taken to terminate all reactions by the addition of NaBH4 in order to stabilize by reduction the open-chain aldehyde form of the dRP moiety.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of 8-kDa domain on ARP adduction to dRP. (A) The flowchart depicts the 3′-end 32P-labeled DNA fragments produced by the successive actions of Ung, APN1, and ARP or 8-kDa proteins. (B) Concentration course of ARP adduction to dRP. An autoradiogram is shown of reactions that contained 3′-32P U·A-25-mer (1 pmol), Ung (0.2 unit), APN1 (1 pmol), and 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 5 mM ARP (lanes 3–9, respectively); lanes 1 and 2 contained 3′-32P U·A-25-mer, and 3′-32P U·A-25-mer and Ung, respectively. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as described in the legend to Figure 3. (C) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram shown in (B). (D) Time course of 8-kDa protein addition to the ARP-dRP adduction reaction. An autoradiogram is shown of reactions that contained 3′-32P U·A-25-mer (1 pmol), Ung (0.2 unit), APN1 (1 pmol), and ARP (5 mM). The 8-kDa protein (1 pmol) was added to the reactions at 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min after ARP addition (lanes 3–8); reactions in lanes 1 and 2 contained 3′-32PU·A-25-mer, Ung, and APN1, and 3′-32P U·A-25-mer, Ung, APN1, and ARP, respectively. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as described in the legend to Figure. 1. (E) Densitometric quantification of the autoradiogram shown in (D). The extent of ARP adduction to dRP is expressed as a percentage of the ARP-dRP-11-mer adduct observed in the absence of 8-kDa protein addition (lane 2).

To determine the relative reactivity of the dRP moiety toward ARP, reactions containing the dRP-11-mer DNA created by Ung and APN1 were supplemented with increasing concentrations of ARP (0.25–5 mM), and the results are shown in Figure 7B. Inspection of the autoradiograph showed that the dRPmoiety was much less reactive toward ARP than either the open-chain aldehyde or the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde. At 3 mM ARP, 26% of the 32P dRP-11-mer migrated as ARP-X-11-mer (Figure 7C). The extent of ARP-X-11-mer formation as a function of ARP concentration did not approach saturation at 5 mM ARP, the highest concentration tested. The minor band just above the dRP-11-mer band was most likely dRP-12-mer. This fragment would result from Ung-APN1-mediated cleavage of 3′-32P-26-mer, which could be produced by terminal transferase if the Cordycepin 5′-triphosphate stock were contaminated with 2′-deoxyadenosine triphosphate. The effect of the 8-kDa domain on ARP adduction to dRP-11-mer was examined by supplementing the ARP reaction with 8-kDa protein at various times (0–30 min) after reaction initiation (Figures 7D and E). When the 8-kDa domain was added at the same time as ARP, no ARP-X-11-mer formation was observed (Figure 7D, lane 3). However, when the 8-kDa protein was added 30 min after ARP, no effect on the amount of adduct formed was observed (Figure 7D, lane 8). These results indicated that elimination of the dRP moiety abolished ARP adduct formation and that the 8-kDa dRPase could not remove an ARP-adducted dRP group.

DISCUSSION

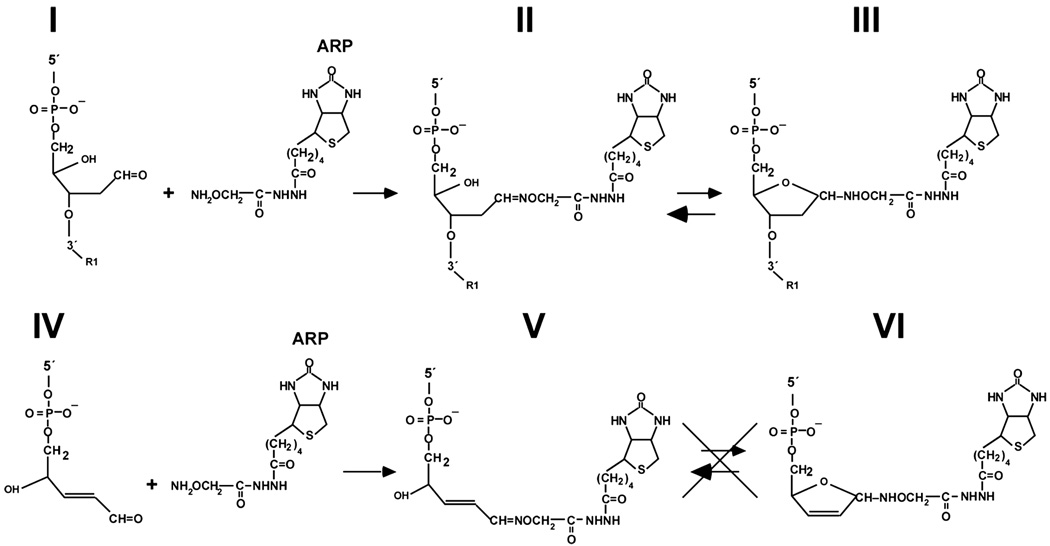

In this report we have characterized the reactivity of the aldehyde reactive probe ARP with a freshly produced AP-site, the 3′-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal moiety produced from an AP-site by AP-lyase-catalyzed β-elimination, and the 5′-deoxyribose phosphate group resulting from AP-endonuclease-catalyzed cleavage of AP-site DNA, during the first 30 to 60 min of formation. The experimental results show that (1) ARP adduction to the open-chain aldehyde form of the AP-site was less efficient than adduction to the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde produced by AP-lyase; (2) that the dRP moiety was the least reactive toward ARP; (3) the reactivity of both the AP-site and the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde moiety was relatively stable over a 30-min incubation period at 37°C; and (4) ARP adducted to the open-chain aldehyde form of the AP-site could be replaced by MX, but the 3′-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal ARP oxime was stable against MX attack. A possible mechanism to account for this difference in reactivity is presented in Figure 8. Just as an AP-site is an equilibrium mixture of open and closed forms, we hypothesize that the open-chain aldehyde ARP oxime (Figure 8, II) can cyclize to form an α- and/or β-hemiaminal (Figure 8, III). In the hemiaminal form, the C1′ anomeric carbon would be vulnerable to a SN2 nucleophilic substitution reaction with MX. The converse reaction, nucleophilic attack by ARP on an open-chain aldehyde MX oxime, was not observed, possibly because the larger ARP molecule was sterically hindered from achieving the required reaction geometry.

FIGURE 8.

Hypothetical equilibrium of the hemiaminal form of an ARP-adducted AP-site. The open-chain aldehyde form of an AP-site (I) undergoes a condensation reaction with ARP to yield an open-chain aldehyde ARP oxime (II) that is in equilibrium with the α,β-hemiaminal form (III). In contrast, the 4-hydroxy-2-pentenal moiety produced by AP-lyase-mediated cleavage of an AP-site (IV) forms an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde ARP oxime upon condensation with ARP (V) that is unable to cyclize (VI).

We observed that approximately 40% of the open-chain aldehyde ARP oxime was resistant to replacement by MX (Figure 6). A possiblemechanism to explain this resistance involves consideration of the steric restraints imposed on bulky adducts by double-stranded DNA and the influence of oxime stereochemistry. DNA structure can have considerable influence on AP-site dynamics. For example, Beger and Bolton[13] reported that whereas an apyrimidinic site opposite A in a duplex oligonucleotide was an equal mixture of the α- and β-hemiacetal forms of 2-deoxy-d-erythro-pentofuranose, an apurinic site opposite C was predominantly a β-hemiacetal. If the syn and anti configurations of the open-chain aldehyde ARP oxime (Figure 8, II) were formed in approximately equal amounts, we speculate that cyclization of the relatively bulky open-chain aldehyde ARP oxime to one particular configuration of the hemiaminal may be hindered by neighboring nucleotides within the duplex DNA oligonucleotide. In that case, about one-half of the open-chain aldehyde ARP oxime would not cyclize and would be resistant to replacement by MX. Alternatively, the α- and β-forms of the ARP hemiacetal are likely to have different hydrogen bonding patterns within the base stack. Weak intrahelical hydrogen bonding may facilitate rotation of one form of the open-chain aldehyde ARP hemiaminal to an extrahelical position where it would be vulnerable to MX replacement.

If we treat the amount of ARP-11-mer produced in the 60-min reactions shown in Figure 7C as an apparent rate, then the rate constant kARP and dissociation constant Kd that characterize ARP adduction to dRP-11-mer can be estimated by fitting the dependence of the observed rate constant kobs on ARP concentration to the equation kobs = k [ARP]/[Kd + (ARP)]. The results are kARP = 729 ± 50 nmol/h and Kd = 4.88 ± 0.6 mM. The high Kd indicates that the affinity of the dRP-11-mer for ARP was low. The relatively low reactivity of the dRP moiety may indicate that nucleophilic attack by the ARP alkoxyamine was sterically hindered by the 5′-phosphate group or that the open-chain aldehyde form of the 5′-end abasic deoxyribose phosphate occurred at a lower frequency compared to AP-site 24-mer. Estimates of kARP and Kd for the reaction of ARP with AP-site 24-mer and 13-mer-3′-4H2Pe were not reliable since the amount of ARP product formed (Figures 2–4) was large. However, we surmise that the kARP for AP-site 24-mer was about the same as for dRP-11-mer, but that the Kd for AP-site 24-mer was in the low micromolar range. Determination of the kARP for the reaction of ARP with 13-mer-3′-P-4H2Pe will require rapid quench experiments.

The results presented here offer insight into the observation made by Talpaert-Borle and Liuzzi[15] that depurinated calf thymus DNA labeled with 14C-methoxyamine lost radioactivity when reacted with nonradioactive methoxyamine: In their experiments, the AP-site open-chain aldehyde oxime containing 14C-methoxyamine underwent nucleophilic attack by unlabeled methoxyamine, resulting in substitution of unlabeled methoxyamine for 14C-methoxyamine. In the absence of methoxyamine, the 14C-methoxyamine-labeled calf thymus DNA was stable.[15] As we have shown here, the problem of oxime substitution can be avoided by first cleaving AP-sites with AP-lyase and then adding the appropriate alkoxyamine reagent, such as ARP or 14C-methoxyamine. These results also suggest that the 3′-α,β-unsaturated DNA aldehyde produced by AP-site β-elimination is more toxic to cells than the AP-site itself, since it can readily form stable adducts with less reactive intracellular nucleophiles.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Macromolecular and Structural Interactions Core of the Environmental Health Sciences Center (Oregon State University, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant P30 ES00210) for assistance with technical analysis. We thank Drs. J. S. Siegel (Institute of Organic Chemistry, University of Zurich), R. S. Lloyd (Oregon Health Sciences University), M.I. Schimerlik (Oregon State University), and W. A. Franklin (Albert Einstein College of Medicine) for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM66245.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Samuel E. Bennett, Department of Environmental and Molecular Toxicology, and the Environmental Health Sciences Center, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA

Joshua Kitner, Department of Environmental and Molecular Toxicology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindahl T. Instability and Decay of the Primary Structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabow L, Stubbe J, Kozarich JW, Gerlt JA. Identification of the Alkaline-Labile Product Accompanying Cytosine Release during Bleomycin-Mediated Degradation of d(CGCGCG) Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1986;108:7130–7131. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drinkwater NR, Miller EC, Miller JA. Estimation of Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Sites and Phosphotriesters in Deoxyribonucleic Acid Treated with Electrophilic Carcinogens And Mutagens. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5087–5092. doi: 10.1021/bi00563a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster PL, Davis EF. Loss of an Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Site Endonuclease Increases the Mutagenicity of N-Methyl-N′-Nitro-N-Nitrosoguanidine to Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1987;84:2891–2895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholes G, Stein G, Weiss J. Action of X-Rays on Nucleic Acids. Nature. 1949;164:709. doi: 10.1038/164709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von Sonntag C. The Chemical Basis of Radiation Biology. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of Depurination of Native Deoxyribonucleic Acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3610–3618. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura J, Swenberg JA. Endogenous Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Sites in Genomic DNA of Mammalian Tissues. Cancer Research. 1999;59:2522–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokoska RJ, McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA. The Efficiency and Specificity of Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Site Bypass by Human DNA Polymerase {eta} and Sulfolobus solfataricus Dpo4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;278:50537–50545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu S-L, Lee S-K, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. The Stalling of Transcription at Abasic Sites Is Highly Mutagenic. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23:382–388. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.382-388.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeb LA, Preston BD. Mutagenesis by Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Sites. Annuual Review of Genetics. 1986;20:201–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manoharan M, Ransom SC, Mazumder A, Gerit JA, Wilde JA, Withka JA, Bolton PH. The Characterization of Abasic Sites in DNA Heteroduplexes by Site Specific Labeling with Carbon-13. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1988;110:1620–1622. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beger RD, Bolton PH. Structures of Apurinic and Apyrimidinic Sites in Duplex DNAs. Journal of the Biological Chemical. 1988;273:15565–15573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coombs MM, Livingston DC. Reaction of Apurinic Acid with Aldehyde Reagents. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1969;174:161–173. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(69)90239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talpaert-Borle M, Liuzzi M. Reaction of Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Sites with [14C]Methoxyamine. A Method for the Quantitative Assay of AP Sites in DNA. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1983;740:410–416. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(83)90089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kow YW. Mechanism of Action of Escherichia coli Exonuclease III. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3280–3287. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubo K, Ide H, Wallace SS, Kow YW. A novel, Sensitive, and Specific Assay for Abasic Sites, the Most Commonly Produced DNA Lesion. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3703–3708. doi: 10.1021/bi00129a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kow YW, Dare A. Detection of Abasic Sites and Oxidative DNA Base Damage Using an ELISA-Like Assay. Methods. 2000;22:164–169. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura J, Walker VE, Upton PB, Chiang SY, Kow YW, Swenberg JA. Highly Sensitive Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Site Assay can Detect Spontaneous and Chemically Induced Depurination under Physiological Conditions. Cancer Research. 1998;58:222–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett SE, Sung J-S. Fidelity of Uracil-Initiated Base Excision DNA Repair in DNA Polymerase Beta-Proficient and -Deficient Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast Cell Extracts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:42588–42600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin JD, Demple B. Analysis of Class II (hydrolytic) and Class I (Beta-Lyase) Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Endonucleases with a Synthetic DNA Substrate. Nucleic Acids Research. 1990;18:5069–5075. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]