Abstract

Objectives

Acute pancreatitis is a necroinflammatory disease that leads to 210,000 hospitalizations in the United States annually. Recent reports suggest that there may be important differences in clinical features between infants/toddlers and older children. Thus, in this study we make a direct comparison between the pediatric age groups in presentation and management trends of acute pancreatitis.

Patients and Methods

We examined all children (ages 0 to 20 years) admitted to Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital with pancreatitis between 1994 and 2007.

Results

Two hundred seventy-one cases met inclusion criteria for acute pancreatitis. Infants and toddlers manifested fewer signs and symptoms of abdominal pain, epigastric tenderness, and nausea compared with older children (43% vs 93%; 57% vs 90%; and 29% vs 76%, respectively; P < 0.05 for all comparisons). They were more likely to be diagnosed by serum lipase than by amylase and to undergo radiographic evaluation (P < 0.05). They had a longer hospital stay (19.5 vs 4 days; P < 0.05) and were less likely to be directly transitioned to oral nutrition (14% vs 71%; P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Infants and toddlers with acute pancreatitis present with fewer classical symptoms and are managed differently from older children. We believe these data will be helpful in evaluating and understanding treatment practices in this age group.

Keywords: acute pancreatitis, amylase, infants, lipase, toddlers

Acute pancreatitis is a necroinflammatory disease of the pancreas that has many associated etiologies such as common bile duct stones, alcohol, trauma, medications, toxins, and ductal defects. Acute pancreatitis accounts for more than 210,000 annual hospital admissions (1) and, tallied with chronic pancreatitis, leads to 31,000 deaths per year (2). Although practice parameters for acute pancreatitis are currently evolving using primarily adult studies, information about children is lacking. Although in children there are several studies examining pancreatitis incidence and etiology (3–7), few have characterized their clinical presentation and management (8,9). We hypothesized that in our pediatric population of acute pancreatitis in New Haven, Connecticut, there are also age-related differences in the management of acute pancreatitis. Indeed, we found that infants and toddlers differ from older children in clinical presentation, level of serum biomarker elevation, type of radiographic evaluation, length of hospitalization, and mode of nutrition.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Group

A retrospective chart review was conducted at Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, New Haven. Children (younger than 21 years) admitted between August 1994 and July 2007 were screened for International Classification of Diseases-9 codes pertaining to pancreatitis. The study was approved by the Yale University School of Medicine institutional review board. Details of the cohort, including referral trends for pancreatitis over time, etiologies, and ethnic breakdown, have been published recently (5).

Inclusion Criteria

The following were our inclusion criteria: Serum amylase or lipase elevated >3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN); radiographic evidence consistent with acute pancreatitis (demonstrating a minimum of pancreatic parenchymal abnormalities or peripancreatic fluid) on ultrasound (US) or computed tomography (CT); serum lipase >1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) (without a nonpancreatic cause for hyperlipasemia); and the presence of 2 of 3 of the following clinical features characteristic of acute pancreatitis: abdominal pain or irritability, nausea or vomiting, and epigastric tenderness.

Cases were excluded if they had chronic pancreatitis documented on CT or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or if they had an incomplete chart record. Children with repeat episodes of acute pancreatitis required a 4-week interval between a prior discharge and a new episode to be considered recurrent. The cohort was divided into 3 groups based on age: infants and toddlers (0–2 years), young children (3–10 years), and adolescents (11–20 years).

Data Collection

Demographic, clinical, laboratory, and management data were collected to characterize 3 key elements of each case: clinical presentation, biochemical presentation, and hospital management. Cases were assigned an etiology based on the reported cause of pancreatitis from the chart record. Etiology for these cases was detailed in our previous publication (5).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by comparing continuous variables using a Student t test, whereas discrete variables were compared using chi-square analysis. A P value <0.05 denotes statistical significance. Data were compiled and analyzed with SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) software.

RESULTS

There were 594 cases identified by International Classification of Diseases-9 codes for pancreatitis. Of these, 271 cases (45.6%) met inclusion criteria, comprising 215 children. Besides the inability to meet diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis, 18 cases were excluded because they had chronic pancreatitis, and 46 had incomplete chart records (5). Two hundred twenty-six cases (81%) met inclusion by strict biochemical criteria, with serum amylase or lipase >3 times ULN. Thirty-three (12%) cases met inclusion because lipase levels were >1.5 times ULN, and they fulfilled clinical criteria. Twelve cases (4%) were included by radiographic evidence alone. The demographic characteristics and clinical presentation of each age group are provided in Table 1. Eighteen percent of patients in the 11 to 20 years age group had recurrent pancreatitis, compared with 7.1% in the 0 to 2 years and 3 to 10 years age groups (P < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Cohort characteristics

| Age group, y | 0–2 | 3–10 | 11–20 | Total cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. pancreatitis episodes or cases | 14 | 59 | 196 | 271 |

| No. patients | 12 | 56 | 150 | 215 |

| Patients with recurrence, % (n) | 7.1 (1) | 7.1 (4) | 18.6 (28) | 15 (33) |

| No. episodes per recurrent patient (SD)# | 4 (0) | 2.5 (1) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.3) |

| Mean age (SD), y | 1.3 (0.7) | 7.1 (2.4) | 16.5 (2.8) | 13.6 (5.5) |

| Male, % | 4 (28.6) | 20 (33.3) | 83 (44.4) | 108 (40) |

| Symptoms≠, % (n) | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 42.9 (6)* | 93.2 (55) | 93.4 (183) | 90 (244) |

| Epigastric tenderness | 57.1 (8)* | 86.4 (51) | 87.2 (171) | 85 (230) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 28.6 (4)* | 69.5 (41) | 78.1 (153) | 73 (198) |

| Etiologies≠, % (n) | ||||

| Biliary | 33.3 (4) | 21.4 (12) | 36.7 (55) | 26.2 (71) |

| Idiopathic | 0 | 28.6 (16) | 22.7 (34) | 18.5 (50) |

| Inborn error of metabolism | 16.7 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0.74 (2) |

| Medication | 16.7 (2) | 26.8 (15) | 25.3 (38) | 20.3 (55) |

| Systemic | 25 (3) | 7.1 (4) | 8.7 (13) | 7.4 (20) |

| Trauma | 25 (3) | 14.3 (8) | 6.7 (10) | 7.7 (21) |

| Viral | 0 | 16.1 (9) | 4 (6) | 5.5 (15) |

In a limited number of patients, a recurrent pancreatitis episode occurred when they were older than their initial age group.

P < 0.05 when comparing between 0 and 2 years and all older age groups.

A patient could have >1 symptom or etiology.

Three key clinical features on presentation were abdominal pain or irritability, nausea or vomiting, and epigastric tenderness. The most common clinical feature was abdominal pain or irritability, seen in 91% of cases. Eighty-six percent presented with epigastric tenderness. Nausea or vomiting was the least common, seen in 74% of cases. Ninety percent of those who met strict biochemical criteria for pancreatitis had abdominal pain or irritability, whereas it was 100% in cases requiring diagnosis by additional criteria. All 3 clinical features were less commonly observed in the 0 to 2 years age group, compared with older children (43% vs 93%; 57% vs 90%; and 29% vs 76% for abdominal pain/irritability, nausea/vomiting, and epigastric pain, respectively; P < 0.05 for all comparisons).

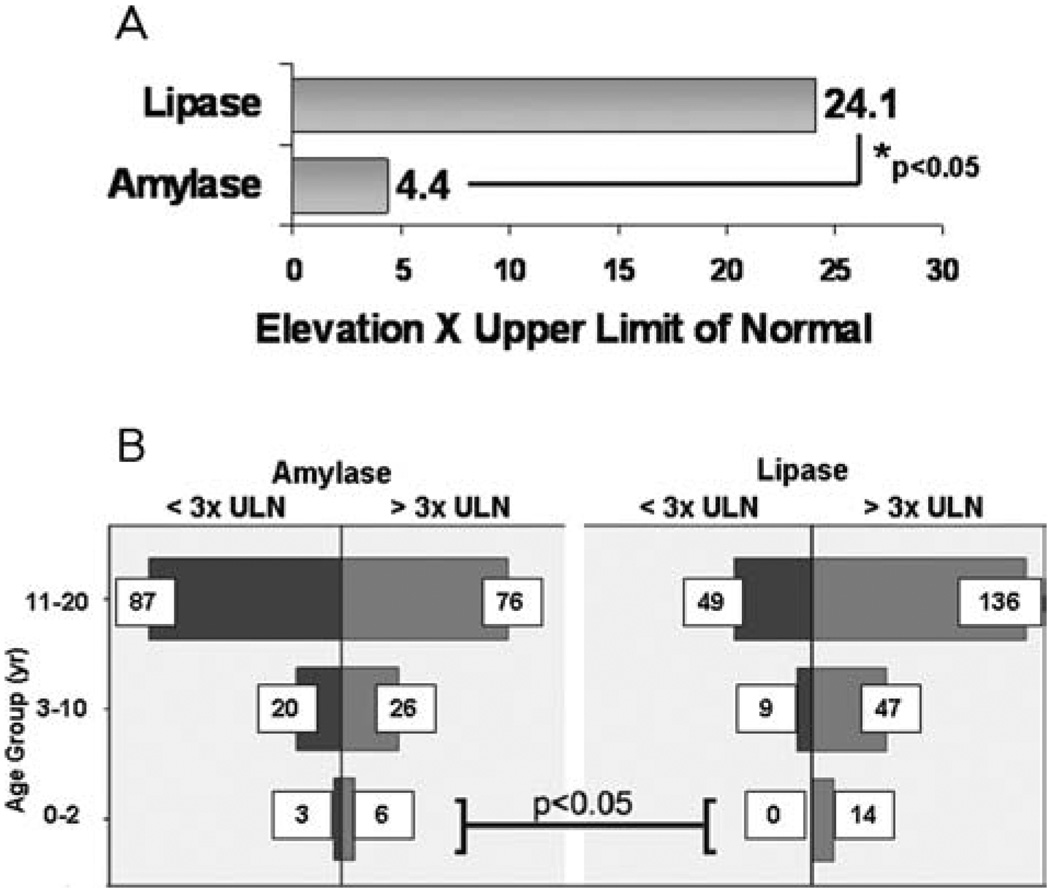

Serum lipase and amylase are the most widely used biochemical indices to diagnose pancreatitis (3,8,10). In all cases, peak lipase levels were 5-fold higher than amylase levels (Fig. 1A; 24.1 times higher than ULN vs 4.4; P < 0.05). Serum lipase levels were >3 times ULN in 100% of the 0 to 2 years age group, whereas amylase elevations >3 times ULN occurred in 66% (Fig. 1B; P < 0.05). Although not statistically significant, a similar trend was noted in the other age groups. Interestingly, patients with recurrent pancreatitis had lower lipase levels than those who had a single isolated episode (18.6 times ULN vs 27.9; P < 0.05).

FIGURE 1.

Serum lipase is a more sensitive biochemical marker for acute pancreatitis than serum amylase in all age groups. (A) Fold increases in serum lipase and serum amylase in the total cohort are depicted. (B) Biochemical elevation >3 times upper limit of normal are depicted in all age groups.

Most cases of pancreatitis (82.6%) underwent radiographic evaluation to establish a diagnosis or examine etiologies such as common bile duct stones (Table 2). US was the most commonly performed test, at nearly twice the rate of CT scanning (79.4% vs 41.9%; P < 0.05). Thirty-eight percent underwent more than 1 radiographic modality; the most common combination was US and CT, performed in 26.3%. The most common findings on US were stones or sludge (53 cases, 29.7%) and pancreatic parenchymal changes (ie, edema or heterogeneity; 51 cases, 28.6%). Common bile duct dilatation was identified in 12.3% of cases that underwent US. The most common findings on CT were pancreatic parenchymal changes (46 cases, 51%) and peripancreatic fluid (36 cases, 39.5%). Overall, signs of pancreatitis were observed by CT scanning in only 59.3% of cases. The 0 to 2 years age group was more likely to undergo US than older children (100% vs 78.1%; P < 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Radiographic modalities performed during hospitalization

| Age group, y | 0–2 | 3–10 | 11–20 | Total cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiography performed (any modality) | 100 (13) | 88 (52) | 81 (159) | 83.8 (224) |

| US performed | 100 (13)* | 84.6 (44) | 76.1 (121) | 79.4 (178) |

| US only | 53.8 (7) | 46.1 (24) | 44.6 (71) | 45.5 (102) |

| US+CT | 38.4 (5) | 32.7 (17) | 22.6 (36) | 26.3 (59) |

| US+CT+ERCP | 0 | 5.7 (3) | 0.6 (1) | 1.7 (4) |

| US+ERCP | 0 | 0 | 8.1 (13) | 5.8 (13) |

| US+MRCP | 7.7 (1) | 0 | 4.4 (7) | 2.2 (5) |

| US+ERCP+MRCP | 0 | 0 | 0.6 (1) | 0.4 (1) |

| CT performed | 38.4 (5) | 51.9 (27) | 37.7 (60) | 41.9 (94) |

| CT only | 0* | 11.9 (7) | 8.7 (17) | 10.4 (24) |

| ERCP performed | 0* | 6.8 (4) | 19.4 (31) | 15.6 (35) |

| ERCP only | 0 | 7.1 (1) | 6.9 (11) | 5.3 (12) |

| ERCP+CT | 0 | 0 | 1.8 (3) | 1.3 (3) |

| ERCP+MRCP | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.7 (2) |

| MRCP performed | 7.7 (1) | 0 | 5 (8) | 4 (9) |

| MRCP only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Percentage of cases (n).

CT=computed tomography; ERCP=endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP; US=ultrasound.

P < 0.05 when comparing between 0 and 2 years and all older age groups.

Hospital management trends including length of hospital stay, rate of gastroenterology (GI) consultation, and modes of nutrition were examined (Table 3). Overall, the median length of stay was 5 days (interquartile range [IQR], 3–10). The 0 to 2 years age group stayed in the hospital longer than older children (19.5 vs 4 days; P < 0.05). The overall rate of GI consultation was 74% (200 cases). The 0 to 2 years age group was more likely than older children to have a GI consultation ordered (92.9% vs 73.3%; P < 0.05). All cases received pain control and intravenous fluids, and most were made non per os (NPO) at presentation (88.6%, 240 cases). The average time to nutrition after being made NPO was 2.1 days. Sixty-five percent were directly transitioned to oral feedings, whereas parenteral or enteral (via a gastric or jejunal tube) nutrition was resorted to in 22.3% and 3.4%, respectively. The 0 to 2 years age group was less likely to be directly transitioned to oral feedings (14.3% vs 67.1%; P < 0.05). Interestingly, there was no change during the 13-year analysis period in length of hospital stay, rate of GI consultation, or modes of nutrition. No cases developed severe acute pancreatitis either with pancreatic necrosis or with multiorgan dysfunction.

TABLE 3.

Hospital management trends

| Age group, y | 0–2 | 3–10 | 11–20 | Total cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median length of stay (IQR) | 19.5 (10.3–37.8)* | 6 (3–11.3) | 4 (3–8) | 5 (3–10) |

| GI consult ordered, % (n) | 100 (13)* | 71.2 (42) | 73.9 (145) | 73.8 (200) |

| NPO at admission, % (n) | 100 (14) | 93 (54) | 97.9 (188) | 88.6 (240) |

| Mean time to nutrition after NPO, days (SD) | 1.6 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.9) | 2.1 (1.7) | 2.1 (1.7) |

| Modality of nutrition after NPO, % (n)** | ||||

| Oral (PO) | 14.3 (2)* | 60.3 (35) | 70.8 (136) | 65.5 (173) |

| Parenteral | 64.2 (9) | 29.3 (17) | 17.2 (33) | 22.3 (264) |

| Enteral | 21.4 (3) | 3.4 (2) | 2.1 (4) | 3.4 (9) |

GI=gastroenterology; IQR=interquartile range; NPO=non per os.

P < 0.05 when comparing between 0 and 2 years and all older age groups.

Data not available in 7 cases in the 3 to 10 years age group.

DISCUSSION

We report in this 13-year analysis of 271 cases of acute pancreatitis in children 4 key comparisons between infants/toddlers (ie, the 0 to 2 years age group) and older children: Infants/toddlers manifest fewer classical signs and symptoms on presentation, they are more likely to be diagnosed by serum lipase than by amylase, they have a longer hospital stay, and they are less likely to be directly transitioned to oral feedings.

To our knowledge, a direct comparison between the very young and older children has not been previously reported, although infants/toddlers with acute pancreatitis have recently been characterized. Kandula et al (8) retrospectively examined 87 infants/toddlers with acute pancreatitis from 1995 to 2004 at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. Several important similarities and differences can be found between their study and our study. Regarding clinical features, 46% presented with abdominal pain or irritability, which is similar to our result of 43% (Table 1). Just more than 50%, however, had nausea/vomiting, compared with our finding of 29%. Nevertheless, data from Pittsburgh corroborate the conclusion that infants/toddlers manifest fewer clinical signs than older children. In our study, the latter group exhibited typical clinical features of pancreatitis in excess of 70%.

Consistent with our findings, Kandula et al (8) also observed that all infants/toddlers diagnosed as having pancreatitis had serum lipase elevations >3 times ULN. By contrast, the same threshold of lipase elevation was noted in 76% of older children in our study (Fig. 1), thus requiring additional criteria for diagnosis. One interpretation of the results is that the serum lipase is a more sensitive marker of pancreatitis in infants/toddlers. However, the higher proportion of serum lipase elevation could also have been a result of our inability to diagnose additional infants/toddlers with acute pancreatitis using criteria such as presenting clinical features or radiographic signs.

Similar to our study, US was the most common imaging modality in infants/toddlers reported by Kandula et al (8), followed by CT. In our direct comparison, infants/toddlers were in fact more likely than older children to undergo US. The practice of choosing US over CT is reasonable because there is a greater risk of long-term complications with ionizing radiation in young children (11). CT scanning aided in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in just less than 60% of our overall cohort of patients. Thus, concerns about radiation exposure and its low sensitivity in diagnosing pancreatitis justify a minimal role for CT scanning in the diagnosis of pancreatitis in children, particularly infants/toddlers.

It is interesting that the length of hospital stay reported by Kandula et al (8) was remarkably similar to that of our cohort of infants/toddlers (19.5 days for both). This is in contrast to a median length of 4 days in our older children as well as in adults admitted with mild acute pancreatitis (12). Additionally, we found that infants/toddlers had higher rates of GI consultation and were less likely than older children to directly transition from NPO to oral feedings. The discrepancy in management trends could be explained by 2 factors. First, several infant/toddlers had complex comorbid medical conditions associated with pancreatitis. For example, 2 had propionic acidemia; management of the disorder required a longer hospital stay to normalize their metabolic status, greater involvement by multiple subspecialties (including GI), and a more gradual transition to oral feedings of a special diet. Second, because pancreatitis is less common in infants/toddlers, physicians are more likely to treat them conservatively.

Although these data require validation, taken together, they may be used as a basic algorithm to facilitate the diagnosis of pancreatitis in infants/toddlers versus older children. First, there should be a lower threshold for suspecting pancreatitis, even in the absence of typical symptoms. Second, lipase should be relied upon far more than amylase levels in this age group. Third, nonimaging modalities should be resorted to more readily to confirm diagnosis of pancreatitis or to evaluate for etiologies of pancreatitis. The limitations of our study, beyond those inherent to its retrospective nature, are that it is based in a single center and all of the cases of pancreatitis were mild. Despite those limitations, we have for the first time reported a direct comparison between infants/toddlers with acute pancreatitis and older children. Because practice parameters in clinical pancreatitis are rapidly evolving for adults, we believe that this study will be helpful in developing similar parameters in children that take into account important differences in presentation and management trends among infants and toddlers.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr Pramod Mistry for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by a Children’s Digestive Health and Nutrition Young Investigator Award (S.Z. Husain) and Summer Undergraduate Award (A.J. Park).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swaroop VS, Chari ST, Clain JE. Severe acute pancreatitis. JAMA. 2004;291:2865–2868. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowenfels AB, Sullivan T, Fiorianti J, et al. The epidemiology and impact of pancreatic diseases in the United States. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:90–95. doi: 10.1007/s11894-005-0045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nydegger A, Heine RG, Ranuh R, et al. Changing incidence of acute pancreatitis: 10-year experience at the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1313–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBanto JR, Goday PS, Pedroso MR, et al. Acute pancreatitis in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1726–1731. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park A, Latif SU, Shah AU, et al. Changing referral trends of acute pancreatitis in children: a 12-year single-center analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:316–322. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818d7db3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez MJ. The changing incidence of acute pancreatitis in children: a single-institution perspective. J Pediatr. 2002;140:622–624. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.123880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weizman Z, Durie PR. Acute pancreatitis in childhood. J Pediatr. 1988;113(1 Pt 1):24–29. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandula L, Lowe ME. Etiology and outcome of acute pancreatitis in infants and toddlers. J Pediatr. 2008;152 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.050. 106.e1-10.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werlin SL, Kugathasan S, Frautschy BC. Pancreatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:591–595. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200311000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nydegger A, Couper RT, Oliver MR. Childhood pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:499–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenner D, Elliston C, Hall E, et al. Estimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:289–296. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson BC, Vander Vliet MB, Hughes MD, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of clear liquids versus low-fat solid diet as the initial meal in mild acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:946–951. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]