Abstract

Cortical networks undergo adaptations during learning, including increases in dendritic complexity and spines. We hypothesized that structural elaborations during learning are restricted to discrete subsets of cells preferentially activated by, and relevant to, novel experience. Accordingly, we examined corticospinal motor neurons segregated on the basis of their distinct descending projection patterns, and their contribution to specific aspects of motor control during a forelimb skilled grasping task in adult rats. Learning-mediated structural adaptations, including extensive expansions of spine density and dendritic complexity, were restricted solely to neurons associated with control of distal forelimb musculature required for skilled grasping; neurons associated with control of proximal musculature were unchanged by the experience. We further found that distal forelimb-projecting and proximal forelimb-projecting neurons are intermingled within motor cortex, and that this distribution does not change as a function of skill acquisition. These findings indicate that representations of novel experience in the adult motor cortex are associated with selective structural expansion in networks of functionally related, active neurons that are distributed across a single cortical domain. These results identify a distinct parcellation of cortical resources in support of learning.

Keywords: cell filling, corticospinal neurons, morphology, sensorimotor cortex

Prior studies have documented alterations of neuronal structure in response to experience and learning (1–6), raising the possibility that these structural modifications might serve as a basis for long-term memory. Within randomly sampled layer V pyramidal neurons of the motor cortex, dendritic branching and arborization (1, 2) and synapse number (5, 7, 8) increase in rats undergoing skilled motor training. New spines reportedly form rapidly after training (9), are stabilized by repeated training, and can persist for extended times beyond the experience (10). Collectively, these observations support the concept that newly formed connections may provide a basis for long-term maintenance of experience.

However, studies examining modifications of neuronal architecture in the context of learning and experience have not focused exclusively on neurons specifically engaged by the experience; instead, random sampling of neurons has been used across the broader cortical functional unit (e.g., forelimb motor cortex or visual cortex). To reach a greater level of understanding regarding the nature of experiential representation in the learning adult brain, it is necessary to examine structural modifications in functionally distinct subsets of neurons based on their relevance to the learning experience. In the present study, taking advantage of specific output patterns of the motor system, we attempt to achieve this level of resolution using a combination of behavioral training and retrograde filling of cortical motor neurons projecting to distinct spinal segments that act as effectors of specific forelimb musculature. We hypothesize that structural modifications in the context of learning a novel motor task requiring the refinement of distal forelimb function will be restricted to subsets of neurons that are engaged by, and most relevant for, adaptations underlying the newly acquired behavior. We now report extensive alterations in both spine density and dendritic complexity only among a highly specific but distributed network of layer V corticospinal motor neurons associated with the control of distal forelimb musculature responsible for forelimb skilled grasping; in contrast, adjacent corticospinal motor neurons that are not engaged in new motor learning are structurally unchanged. Thus, cortical resources are specifically allocated to functionally interrelated neuronal populations that are recruited by learning in adulthood.

Results

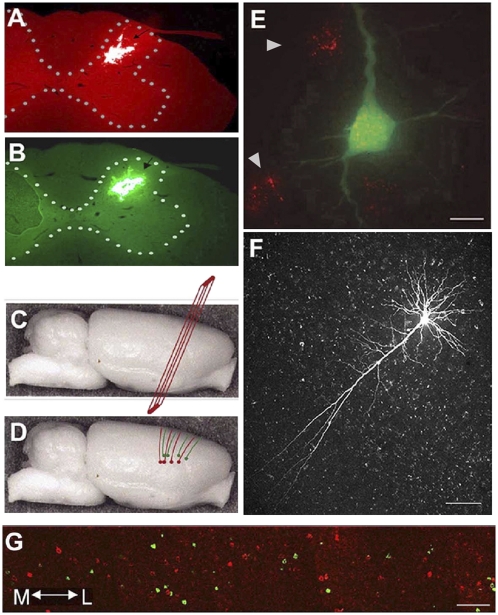

A combination of fluorescent retrograde tracing and intracellular filling was used to examine the effects of forelimb skilled motor training on spine density and dendritic complexity in apical and basilar dendrites in distinct populations of layer V cortical pyramidal neurons. Before behavioral training, all subjects underwent injections of retrogradely transportable tracers into the spinal cord to identify cortical motor neurons projecting to specific spinal segments. In rats, the C8 spinal cord segment contains lower motor neurons that activate muscles controlling distal forelimb movements required for grasping (11), whereas lower motor neuron pools located in the C4 spinal segment are associated with control of proximal forelimb, shoulder and neck musculature (11, 12). To selectively identify layer V corticospinal populations providing innervation to spinal segments associated with distal forelimb movements, subjects received injections of red fluorescent latex microspheres within the dorsal gray matter of the C8 spinal segment. Corticospinal motor neuron populations controlling proximal forelimb musculature were labeled in the same subjects by injecting green fluorescent latex microspheres within the dorsal gray matter of C4 (Fig. 1 A and B).

Fig. 1.

Retrograde tracing and filling of corticospinal neurons. (A) Red latex microspheres injected into the dorsal horn (arrow) of the C8 spinal cord segment. (B) Green latex microspheres injected into the dorsal horn (arrow) of the C4 spinal cord segment. (C) Modified coronal sections cut with 20° forward angle (red plane) compared with normal coronal sections. (D) Projection pattern of apical dendrites of corticospinal neurons (red. C8; green, C4). (E) Representative neuron labeled by retrogradely transported red latex microspheres in the cell body filled by Lucifer Yellow (green); note several single labeled neurons (red, at arrowheads) around the filled neuron. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (F) Representative Lucifer Yellow–filled corticospinal neuron in layer V of the motor cortex. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (G) Photographic montage illustrating retrogradely labeled layer V corticospinal neurons projecting either to C8 (red) or C4 (green) spinal segments. Tracers do not colocalize within individual layer V cells, indicating that corticospinal projections do not collateralize across the C4 and C8 segments. (Scale bar: 60 μm.)

Two weeks after injection of retrograde tracers, rats were divided into the following behavioral training groups. (i) Forelimb skilled grasping subjects (n = 10) were trained (60 trials per day for 14 d) to retrieve small reward pellets through a slot in a Plexiglas test chamber, as previously described (13, 14). This forelimb skilled grasping task requires hundreds of trials for Fischer rats to achieve proficiency, typically attaining 70–80% accuracy in food pellet retrieval by the end of 14 d of training (14). (ii) Untrained control subjects (n = 9) underwent an identical period of handling and spent comparable amounts of time in the Plexiglas test chamber. Untrained control rats did not execute reaches but had a comparable number of reward pellets placed directly into their mouths. (iii) Partially active control subjects (n = 8) spent comparable time in the testing chamber and underwent an identical number of reach trials. Unlike the forelimb skilled grasping subjects, active control rats were not allowed to grasp the food reward; instead, the food reward was placed in the mouth of the rat after each reach effort. The extent of motor learning taking place with this form of partially active “control” training is not completely understood; however, prior studies suggest that only partial refinement of distal forelimb motor control occurs as the rat reaches for, but does not fully grasp, the food reward (5).

After completion of behavioral training, subjects were perfused and 200-μm slices were obtained from the primary motor cortex in planes perpendicular to the cortical surface (Fig. 1 C and D). This orientation captured the complete basilar and apical arbors of layer V corticospinal neurons. Cortical slices were mounted onto glass slides and examined under a 40× water immersion objective using epifluorescence. Corticospinal neurons projecting to either C4 or C8 were distinguishable based on their differing emission spectra. One or two retrogradely labeled cells per slice were penetrated by a small-diameter glass microelectrode and iontophoretically filled with Lucifer Yellow (Fig. 1F). A total of 74 neurons were filled among the 10 subjects in the skilled grasping group, 74 neurons filled among the 8 animals in the partially active control group, and 74 neurons filled among the 9 animals in the untrained control group. Sections containing Lucifer Yellow-filled neurons were then postfixed and subjected to high-resolution 3D confocal microscopy and reconstruction to quantify several morphological parameters. Dendritic spine density was quantified per 10-μm segment in second-order or greater apical, and third-order or greater basilar, dendrites. Overall dendritic complexity was determined for both apical and basilar arbors of Lucifer Yellow-filled cells using NeuroLucida software. Dendritic complexity was assessed using both a branch order analysis (15) and Sholl analysis (16).

Forelimb Skilled Training Selectively Enhances the Structure of C8-Projecting but Not C4-Projecting Corticospinal Motor Neurons.

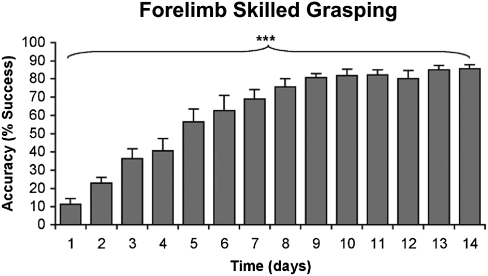

After 14 d of behavioral training, forelimb skilled grasping rats exhibited a significant improvement in reaching performance, with successful pellet retrieval increasing from 11.4 ± 3.0% of trials on the first day of testing to 85.7 ± 2.2% on the last day of training (P < 0.0001, repeated-measures ANOVA; Fig. 2). In addition, using intracortical microstimulation mapping, we found that skilled grasp training in F344 rats resulted in a significant 28.2 ± 6.5% increase in the number of cortical sites associated with distal forelimb representations (wrist and digits) compared with nontrained subjects (P = 0.02, two-tailed t test; Fig. S1). In contrast, the size of proximal forelimb representation was reduced by 19.2 ± 2.6% in trained subjects compared with untrained controls (P = 0.04; two-tailed t test). Thus, consistent with previous reports in other rat strains (5, 17), our findings indicated that acquisition of the skilled grasping task is associated specifically with the refinement of outputs controlling distal, but not proximal, forelimb movements.

Fig. 2.

Acquisition of forelimb skilled grasping. Performance on a forelimb skilled grasping task significantly improved over a 14-d training period (***P < 0.0001; repeated-measures ANOVA).

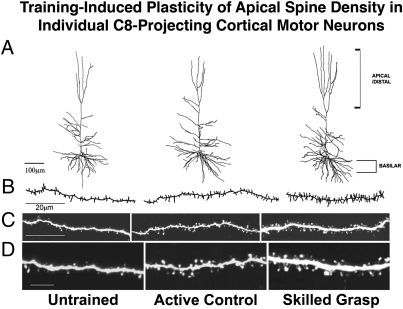

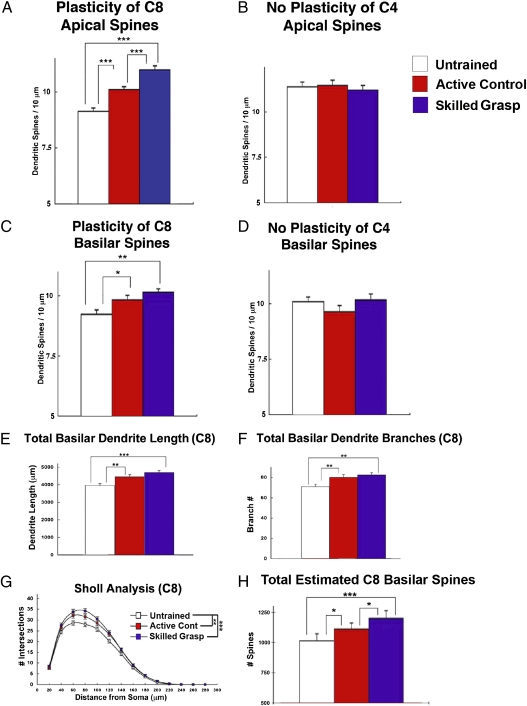

Forelimb skilled grasp training significantly augmented several measures of structural plasticity in layer V pyramidal neurons projecting to C8, but did not affect any parameter of adjacent C4-projecting neurons (Figs. 3 and 4). Skilled grasp training resulted in a significant 22.5 ± 2.3% increase in the density of spines located on distal apical dendrites of layer V cortical pyramidal neurons that project to the C8 spinal segment, compared with untrained control subjects (P < 0.0001; Figs. 3 and 4A). Partially active controls exhibited increased distal apical spine densities that were approximately half as extensive as those observed in forelimb skilled grasp animals (P < 0.0001, Fisher's post hoc test), likely reflecting partial recruitment of C8 motor neurons during reaching compared with forelimb skilled grasping. Forelimb skilled grasping also resulted in a significant increase in basilar distal spine density of C8-projecting cells compared with untrained controls (P < 0.001, Fig. 4C), whereas C4-projecting neurons exhibited no change at all (P = 0.8; Fig. 4D). Once again, partially active controls exhibited intermediate spine density changes in C8-projecting neurons, differing significantly from inactive controls (P < 0.05, Fisher's post hoc test) and trending toward difference from forelimb skilled grasping animals (P = 0.19, Fisher's post hoc test; Fig. 4C).

Fig. 3.

Training-induced plasticity of C8-projecting neurons in motor cortex. (A) Neurolucida reconstructions of representative corticospinal neurons projecting to C8 in either untrained (Left), partially active control (Center), or skilled grasping (Right) animals. (B) Neurolucida reconstructed segments of representative apical dendrites from untrained (Left), partially active control (Center), and skilled grasping (Right) subjects. (C) Representative Lucifer Yellow-filled segments of apical dendrites from untrained (Left) partially active control (Center), and skilled grasping (Right) rats, illustrating increased spine density after skilled motor training. (D) Higher magnification of images in C. (Scale bars: A, 100 μm; B and C, 20 μm; D, 5 μm.)

Fig. 4.

Skilled grasp training selectively enhances structural plasticity in C8-projecting layer V corticospinal motor neurons. (A) A 22.5 ± 2.3% increase in spine density occured on distal apical dendrites of C8-projecting corticospinal neurons in rats that underwent forelimb skilled grasping; active controls show intermediate changes. ***P < 0.0001; **P < 0.001. (B) In contrast, apical dendrites of C4-projecting neurons exhibit no change at all in spine density (P = 0.9). (C) Similarly, there are significant changes in the density of basilar spines in skilled grasp trained rats and partially active controls that differ significantly from those of untrained controls. **P < 0.001; *P < 0.01. (D) In contrast, basilar dendrites of C4-projecting neurons exhibit no change at all in spine density (P = 0.8). (E) Measures of dendritic complexity also changed as a function of skilled grasp training, including total basilar dendritic length (***P < 0.0001; **P < 0.001). (F) Total dendritic branch number (**P < 0.001), and (G) Sholl analysis (***P < 0.0001; **P < 0.001). (H) Estimates of total basilar spine number indicate that skilled grasp training leads to significantly greater increases compared with partially active controls and untrained subjects (***P < 0.0001; *P < 0.05).

Analysis of dendritic morphology also revealed significant increases in complexity of C8-projecting neurons as a function of forelimb skilled training compared with untrained controls (Fig. 4 E–G). Skilled grasping rats exhibited significant increases in total basilar dendritic length and basilar dendritic branching compared with untrained rats (P < 0.0001 and P < 0.001, respectively). Moreover, Sholl analysis indicated a shift toward greater overall complexity of dendritic branching as a consequence of forelimb skilled training (P < 0.0001, Fig. 4G). Consistent with measures of spine density, partially active controls tended to exhibit changes of intermediate extent compared with skilled grasping animals and inactive controls (Fig. 4 E and F). In contrast, C4-projecting corticospinal motor neurons exhibited no change in basilar dendrite morphological parameters in any group (Fig. S2). Although the density of apical spines significantly increased with skilled motor training (as noted above), apical dendritic morphology (i.e., dendrite length and branching) did not change.

We generated an estimate of the total number of basilar spines on terminal segments by multiplying the spine density of distal basilar dendrites by the total measured length of distal basilar dendrites. Skilled grasping animals exhibited a significant 35.5 ± 5.9% increase in the estimated total number of basilar spines on terminal segments compared with untrained animals (P < 0.0001, Fisher's post hoc test; Fig. 4H). Skilled grasping animals also differed significantly on this measure from partially active controls (P < 0.05, Fig. 4H). In contrast, total estimated spine number on terminal basilar branches did not differ in C4-projecting neurons in any group (ANOVA, P = 0.23).

Consistent with the preceding findings suggesting that training specifically activates C8-projecting layer V corticospinal neurons, expression of the immediate early gene c-fos was significantly greater in C8-projecting (51.5 ± 4.9% of cells) versus C4-projecting (29.4 ± 4.3% of cells) neurons in rats undergoing forelimb skilled grasping (P = 0.025) compared with cell numbers in untrained rats (25.8 ± 4.4%) (Fig. S3).

C8- and C4-Projecting Neurons Are Interspersed and Distributed Across the Motor Cortical Domain.

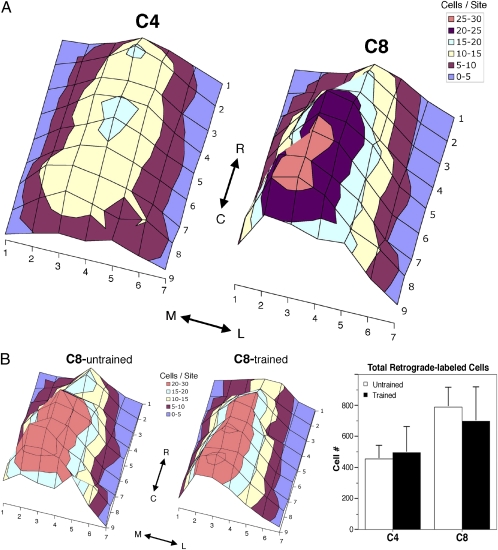

The preceding morphological data suggest that learning in the adult brain is mediated by an elaboration of structure in activated subsets of neurons within a functional cortical domain. We next examined where these distinct subsets of cells are located: Are they clustered together into functionally related subgroups of neurons within the motor cortex (e.g., a set of clustered C8-projecting neurons), or are they broadly distributed throughout motor cortex among other corticospinal projection neurons (e.g., are C8-projecting neurons interspersed with C4-projecting neurons)? Accordingly, this analysis examined whether learning-related changes in structure occur in specific, small cortical domains containing neurons of related function, or whether learning involves the modification of a dispersed neuronal network within a cortical functional domain. We mapped the distribution of retrogradely labeled C8-projecting and C4-projecting neurons both before and after skilled grasp training. We find that C8- and C4-projecting neurons are interspersed throughout the motor cortex with an overlapping distribution (Figs. 1G and 5A); C8- and C4-projecting neurons are not simply parcellated into separate motor subregions. In addition, these distributions do not change as a function of motor training (Fig. 5B). Thus, corticospinal output from the motor cortex is organized as a distributed network of overlapping neuronal populations with distinct functions and projection patterns.

Fig. 5.

Neuronal organization in motor cortex: Interspersion of C8- and C4-projecting corticospinal cells. (A) Spinal cord injections of fluorescent microspheres resulted in retrograde labeling of cells throughout the forelimb area of the primary motor cortex. Mapping of the distribution of retrogradely labeled neurons reveals that C8- and C4-projecting neurons, which control distal and proximal forelimb musculature, respectively, exhibit no significant difference in cell distribution (P = 0.3 ANOVA group × rostral/caudal location). C8 injections labeled 67% more layer V cells than did injections at the C4 level in the same animal (P = 0.004; paired t test). (B) Skilled grasp training did not alter the distribution or total number of retrogradely labeled cells among either C8- or C4-projecting neurons (C8 distribution: P = 0.4, repeated-measures ANOVA across medial- to-lateral locations; C8 number: P = 0.7, unpaired t test; C4 distribution: P = 0.6; C4 number: P = 0.9).

Neurons double-labeled for green and red microspheres were not detected in either trained or untrained subjects, indicating that these distinct subpopulations of corticospinal neurons do not collateralize across the C4 and C8 spinal segments. Moreover, there was no change in the distribution and/or number of cortical neurons back-labeled by tracer injections into C8 and C4 segments of the spinal cord after motor learning compared with the untrained state (Fig. 5), suggesting that neuronal projections within the spinal cord are not modified significantly as a function of skilled grasp training.

Discussion

Results from this study indicate that behavioral experience can extensively drive anatomical plasticity within relevant cortical domains to an extent not previously appreciated, and that these structural modifications are remarkably restricted to subsets of neurons that are actively engaged by the learning experience. The restriction of structural change to a functionally interrelated subset of layer V neurons projecting specifically to the C8 segment of the spinal cord, as opposed to broader ensembles of cortical neurons that project to different levels of the cervical spinal cord, provides clear and unprecedented evidence for neuron-specific, use-dependent structural plasticity in the learning adult brain.

The present findings also provide insight regarding cortical organization and the parcellation of neural resources that mediate learning. Within the motor cortex, we identify an interspersed network of motor neurons that project to distinct functional levels of the spinal cord. Both C8-projecting and C4-projecting neurons are anatomically distributed throughout the forelimb region of the motor cortex, and this fundamental organization does not change as learning occurs. Moreover, only the C8-projecting neuronal population exhibits extensive structural plasticity in the context of acquiring a distal forelimb-specific behavior, with a significant elaboration of spines and an increase in dendritic complexity, whereas C4-projecting neurons are unchanged following the completion of learning. These findings suggest that learning is encoded within networks of functionally related neurons that are distributed across a cortical domain.

Consistent with our mapping of the distribution of motor neurons, recent studies have demonstrated that intracortical microstimulation-evoked movements are associated with the activation of sparse and distributed sets of layer V cells rather than the activation of those neurons nearest the stimulating current source (18). Moreover, prior studies suggest that plasticity of cortical motor maps during skilled grasp training results from modulation of lateral cortical connections within these networks (19–22). Therefore, an increase in spines selectively within the C8-projecting pool could reflect an increase in excitatory inputs targeting this cell population and an enhanced probability of activating the network of C8-projecting neurons upon intracortical stimulation. The structural modifications that we identified across this distributed network as a consequence of training may provide a long-term substrate for synaptic plasticity in this neuronal population. Recent studies have indicated that structural modifications induced by experience can far outlast the initial experience, suggesting a basis for long-term storage of information (9, 10). Moreover, synaptic plasticity within newly generated structural elements may enable rapid reactivation of representations for previously encoded experiences (10). Such an interpretation would be consistent with prior studies indicating that shifts in motor maps can be rapidly reactivated several months after a skilled motor behavior was learned (23).

The amount of structural plasticity in neurons recruited to perform a skilled grasping behavior ranged from a 22% increase in distal apical spine density to a 34% increase in the calculated total distal basilar spine number. The magnitude of these increases substantially exceeds findings of previous studies that randomly sampled motor cortex neurons rather than examining unique subsets of motor cortex neurons that are specifically engaged during learning. The greater magnitude of spine increase identified in this study is likely a reflection of the analysis of the specific subpopulation of neurons undergoing modification as a result of learning, without dilution by nonused neurons such as C4-projecting cells. The analysis of functionally related subsets of neurons in the present study also demonstrated a remarkably small variability in mean spine number among functionally related (e.g., C8-projecting) neurons. The identification of structural homogeneity among functionally related neurons is, to our knowledge, unique and has not been detected previously in nonspecific cell sampling studies. The enhanced sensitivity resulting from studying a highly specific neuronal population based on projection pattern also likely accounts for the finding that intermediate changes in spine density and dendritic complexity were detected in partially active controls; previous studies did not find differences between partially active and inactive controls (5). Indeed, the identification of intermediate changes in spine density in partially active animals supports the general association of structure with function arising from this work.

In summary, findings from this study demonstrate that structural refinement is highly restricted to a specific yet dispersed neuronal network that is engaged by novel behavior. C8-projecting neurons actively engaged while acquiring a skilled motor behavior undergo extensive structural plasticity, and are likely responsible for the refinements in distal forelimb function underlying improvements in performance; adjacent C4-projecting neurons, which are not involved in aspects of the behavior that undergo specific refinement, remain unchanged by the experience.

Methods

A total of 62 male Fischer 344 rats weighing 150--200 g at study onset were used in this study: 31 rats were used to identify effects of motor learning on structural plasticity, 12 rats for mapping studies, 8 rats to identify effects of training on patterns of neuronal activation, and 11 rats to characterize the distribution of corticospinal cells innervating the C4 and C8 spinal segments. Subjects were housed in standard laboratory cages on a 12 hr light/dark cycle, and all procedures and animal care adhered strictly to American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, Society for Neuroscience, and institutional guidelines for experimental animal health, safety, and comfort.

To specifically identify corticospinal cells innervating the C8 spinal segment, red fluorescent latex microspheres (Lumafluor) were injected bilaterally into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord at the C8 level; corticospinal cells innervating the C4 levels were similarly labeled by injecting green fluorescent microspheres into the C4 level of the spinal cord (detailed procedures can be found in the supporting information file). Two weeks following tracer injections, skilled motor training was carried out using a single pellet test chamber as previously described (14). To control for potential effects related to handling or exposure to the test chamber, a group of nonreaching (untrained) animals was included. Also, an additional group of “partially active controls” were trained on a variation of the forelimb skilled grasping task. These animals were trained to reach for reward pellets placed outside the slot, but the pellet was withdrawn before the animal could grasp it.

Following behavioral training, animals were perfused, and their brains were cut in 400-μm slices in the coronal plane. C8- and C4-projecting cells were identified by the presence of red or green fluorescent tracers respectively, and one to two cells per slice were impaled and filled with Lucifer Yellow as previously described, with modifications (24, 25). Filled cells were then examined using a two-photon microscope, visualized and reconstructed using Neurolucida (MBF Bioscience), and analyzed using NeuroExplorer (MBF Bioscience). Spine density was determined by quantifying the number of spines per defined length of dendrite, and dendritic complexity was assessed using either a branch order (15) or a Sholl analysis (16).

The distribution of corticospinal motor neurons projecting to the C4 and C8 spinal segments was characterized in a separate set of animals. In these animals, corticospinal neurons were retrogradely labeled by tracer injections into C8 and C4 spinal cord segments, and rats were then subjected to forelimb skilled reach training (n = 6) or remained untrained (n = 5), as described above. Following training, the distribution of retrogradely labeled cells was mapped across the medial to lateral extent of the caudal forelimb area in a series of 40-μm coronal sections.

Patterns of neuronal activation induced by skilled motor training were assessed by examining the expression of the immediate early gene c-fos. Retrogradely labeled rats underwent five days of skilled motor training (n = 4) or equivalent periods of exposure to the testing chamber without motor training (n = 4) and were killed 60 min after the final training session. The number of C4- and C8-projecting cells containing c-fos immunoreactivity (using antibody SC-052) was quantified in a series of 40-μm sections.

The impact of skilled forelimb motor training on cortical motor representations was assessed using standard intracortical microstimulation techniques (5, 14, 17). Cortical maps were derived bilaterally from six trained and six untrained rats, and the area associated with distal (wrist and digits) and proximal (elbow and shoulder) forelimb movements was quantified.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Nagahara for technical assistance and advice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AG10435, the Veterans Administration, and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1014335108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Greenough WT, Larson JR, Withers GS. Effects of unilateral and bilateral training in a reaching task on dendritic branching of neurons in the rat motor-sensory forelimb cortex. Behav Neural Biol. 1985;44:301–314. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(85)90310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Withers GS, Greenough WT. Reach training selectively alters dendritic branching in subpopulations of layer II-III pyramids in rat motor-somatosensory forelimb cortex. Neuropsychologia. 1989;27:61–69. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(89)90090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bury SD, Jones TA. Unilateral sensorimotor cortex lesions in adult rats facilitate motor skill learning with the “unaffected” forelimb and training-induced dendritic structural plasticity in the motor cortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8597–8606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08597.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adkins DL, Bury SD, Jones TA. Laminar-dependent dendritic spine alterations in the motor cortex of adult rats following callosal transection and forced forelimb use. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:35–52. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleim JA, et al. Cortical synaptogenesis and motor map reorganization occur during late, but not early, phase of motor skill learning. J Neurosci. 2004;24:628–633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3440-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prusky G, Whishaw IQ. Morphology of identified corticospinal cells in the rat following motor cortex injury: Absence of use-dependent change. Brain Res. 1996;714:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleim JA, Lussnig E, Schwarz ER, Comery TA, Greenough WT. Synaptogenesis and Fos expression in the motor cortex of the adult rat after motor skill learning. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4529–4535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04529.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones TA, Chu CJ, Grande LA, Gregory AD. Motor skills training enhances lesion-induced structural plasticity in the motor cortex of adult rats. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10153–10163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-10153.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu T, et al. Rapid formation and selective stabilization of synapses for enduring motor memories. Nature. 2009;462:915–919. doi: 10.1038/nature08389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofer SB, Mrsic-Flogel TD, Bonhoeffer T, Hübener M. Experience leaves a lasting structural trace in cortical circuits. Nature. 2009;457:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature07487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenna JE, Prusky GT, Whishaw IQ. Cervical motoneuron topography reflects the proximodistal organization of muscles and movements of the rat forelimb: A retrograde carbocyanine dye analysis. J Comp Neurol. 2000;419:286–296. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000410)419:3<286::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callister RJ, Brichta AM, Peterson EH. Quantitative analysis of cervical musculature in rats: Histochemical composition and motor pool organization. II. Deep dorsal muscles. J Comp Neurol. 1987;255:369–385. doi: 10.1002/cne.902550305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whishaw IQ. Loss of the innate cortical engram for action patterns used in skilled reaching and the development of behavioral compensation following motor cortex lesions in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:788–805. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conner JM, Culberson A, Packowski C, Chiba AA, Tuszynski MH. Lesions of the Basal forebrain cholinergic system impair task acquisition and abolish cortical plasticity associated with motor skill learning. Neuron. 2003;38:819–829. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman PD, Riesen AH. Evironmental effects on cortical dendritic fields. I. Rearing in the dark. J Anat. 1968;102:363–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sholl DA. Dendritic organization in the neurons of the visual and motor cortices of the cat. J Anat. 1953;87:387–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleim JA, Barbay S, Nudo RJ. Functional reorganization of the rat motor cortex following motor skill learning. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:3321–3325. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Histed MH, Bonin V, Reid RC. Direct activation of sparse, distributed populations of cortical neurons by electrical microstimulation. Neuron. 2009;63:508–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rioult-Pedotti MS, Friedman D, Donoghue JP. Learning-induced LTP in neocortex. Science. 2000;290:533–536. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rioult-Pedotti MS, Friedman D, Hess G, Donoghue JP. Strengthening of horizontal cortical connections following skill learning. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:230–234. doi: 10.1038/678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess G, Donoghue JP. Long-term potentiation of horizontal connections provides a mechanism to reorganize cortical motor maps. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:2543–2547. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Froemke RC, Merzenich MM, Schreiner CE. A synaptic memory trace for cortical receptive field plasticity. Nature. 2007;450:425–429. doi: 10.1038/nature06289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karni A, et al. Functional MRI evidence for adult motor cortex plasticity during motor skill learning. Nature. 1995;377:155–158. doi: 10.1038/377155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buhl EH, Lübke J. Intracellular lucifer yellow injection in fixed brain slices combined with retrograde tracing, light and electron microscopy. Neuroscience. 1989;28:3–16. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao WJ, Zheng ZH. Target-specific differences in somatodendritic morphology of layer V pyramidal neurons in rat motor cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2004;476:174–185. doi: 10.1002/cne.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.