Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are the main lymphoid population in the maternal decidua during the first trimester of pregnancy. Decidual NK (dNK) cells display a unique functional profile and play a key role in promoting tissue remodeling, neoangiogenesis, and immune modulation. However, little information exists on their origin and development. Here we discovered CD34+ hematopoietic precursors in human decidua (dCD34+). We show that dCD34+ cells differ from cord blood- or peripheral blood-derived CD34+ precursors. The expression of IL-15/IL-2 receptor common β-chain (CD122), IL-7 receptor α-chain (CD127), and mRNA for E4BP4 and ID2 transcription factors suggested that dCD34+ cells are committed to the NK cell lineage. Moreover, they could undergo in vitro differentiation into functional (i.e., IL-8– and IL-22–producing) CD56brightCD16−KIR+/− NK cells in the presence of growth factors or even upon coculture with decidual stromal cells. Their NK cell commitment was further supported by the failure to undergo myeloid differentiation in the presence of GM-CSF. Our findings strongly suggest that decidual NK cells may directly derive from CD34+ cell precursors present in the decidua upon specific cellular interactions with components of the decidual microenvironment.

Keywords: natural killer cell development, natural killer receptor, immunity in pregnancy

Natural killer (NK) cells are an important component of innate immunity. Their best characterized functions are the capability of killing virus-infected or tumor cells and releasing proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Recently, their possible role in defense against other pathogens, including bacteria, has been suggested (1–4). NK cell function is primarily regulated by a number of activating and inhibitory receptors, some of which recognize MHC class I molecules (5–8). Although the prevalent role of NK cells is to defend the host against infections and possibly tumors, recent studies have indicated that they may also display different functional capabilities. For example, freshly isolated peripheral blood NK cells, exposed in vitro to cytokines such as IL-4 or IL-18, rapidly lose their capability of killing and of releasing IFN-γ and TNF-α. This may have profound consequences not only on the quality and strength of innate immune responses, but also on downstream adaptive immune responses (9). These data suggest that the in vivo microenvironment may influence NK cell function. In this context, in atopic patients, NK cells were shown to display poor cytolytic activity and low IFN-γ production (10).

NK cells isolated from human decidua (dNK cells) during the first trimester of pregnancy represent 50% to 70% of the total lymphoid cells present in this tissue and display a unique functional profile (11–15). Thus, they release IL-8 (also known as CXCL8), VEGF, stromal-derived factor–1 (also known as CXCL12), and IFN-γ–inducing protein 10 (also known as CXCL10)—cytokines that play a major role in tissue remodeling and/or neoangiogenesis (15–17). In addition, dNK cells are involved in the induction of CD4+ regulatory T cells that are thought to play a major role in the inhibition of maternal immune response and in tolerance induction (18–20).

A number of studies in vitro as well as in vivo [e.g., in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)] revealed that NK cells originate from CD34+ hematopoietic precursors (21–27). CD34+ cells are present mainly in the bone marrow (BM), but they can be isolated also from peripheral blood (PB) and cord blood (CB). CD34+ cells derived from these sources are routinely used in HSCT because of their capability of reconstituting all hematopoietic cell lineages (28–31). In addition, CD34+ cells have been identified and isolated from other tissues, including thymus, lymph nodes (LNs), and tonsils (30, 32–38). Thymic CD34+ cells can give rise to dendritic cells and NK cells (32–35). In LNs, CD34+ cells were identified, together with other cell precursors corresponding to different stages of NK cell maturation. Remarkably, purified LN CD34+ cells could undergo in vitro differentiation into NK cells, suggesting that LN NK cells could, at least in part, derive directly from LN CD34+ cells (36–38). Regarding dNK cells, little is known about their origin and development, although they are generally thought to derive from PB NK cells migrating to decidua or to develop from endometrial immature NK cells (39).

In this study, we demonstrate that NK cell lineage-committed CD34+ cells are present in human decidua (i.e., dCD34+) and can undergo in vitro differentiation into functional CD56brightCD16− NK cells in the presence of suitable growth factors or even upon coculture with decidual stromal cells (dSC) in the absence of cytokines.

Results

Presence of CD34+ NK-Committed Precursors in Human Decidua.

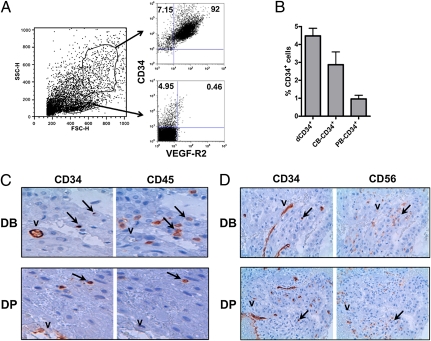

Mononuclear-enriched cell suspensions isolated from human decidua were analyzed for the surface expression of CD34 antigen. Cytofluorimetric analysis revealed that CD34+ cells represent a sizable fraction of the cell samples analyzed. As CD34 antigen is expressed not only by hematopoietic precursors but also by vascular endothelial cells (40), we further investigated whether the cell suspension derived from decidual tissues contained both cell types. To this end, we evaluated the expression of the endothelial cell marker VEGF receptor 2 (VEGF-R2; also called CD309; Fig. 1A). CD34+VEGF-R2+ cells were mainly confined to cells characterized by the morphological parameters of high forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC). Conversely, the presence of CD34+VEGF-R2− hematopoietic precursors was detected only among mononuclear cells displaying low FSC and SSC parameters. The population of CD34+ cells in the lymphoid-gated cell fraction was relatively high and comparable to that of CB (Fig. 1B). In view of this finding, we further performed immunohistochemical analysis of samples derived from decidua basalis (DB) and decidua parietalis (DP) to assess the tissue location of CD34+ cells. CD34-specific mAb intensively stained endothelial cells of the vascular structures (Fig. 1C). However, other CD34+ cells were scattered in both decidual tissues analyzed. Serial sections from the same region revealed the coexpression of CD45 antigen by some of these cells, indicating that they belong to the leukocyte lineage. As NK cells are the predominant lymphoid population in human decidua, we also analyzed their distribution in this tissue. Staining with CD56-specific mAb showed numerous positive cells. All these cells did not express CD34 as revealed by serial sections (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Discovery of CD34+ hematopoietic precursors in human decidua. (A) Analysis of enriched mononuclear cells, isolated from decidua, for the morphological parameters SSC and FSC. Cells characterized by high or low SSC and FSC were gated and analyzed for the expression of CD34 and VEGF-R2 by immunofluorescence. Data refer to a representative experiment among three performed. (B) Comparative analysis of the percentages of CD34+ cells in mononuclear cell suspensions isolated from decidua compared with CB and PB cells. Data are expressed as mean percentage ± SEM of five independent experiments. (C and D) Immunohistochemical analysis of decidual tissues, including DB and DP. (C) Staining of serial sections from the same region with CD34- or CD45-specific mAbs, respectively. The arrows indicate cells stained with both mAbs. V indicates the dCD34+CD45− vessels. (Magnification: 60×.) (D) Staining of serial sections of DB and DP with CD34- or CD56-specific mAbs. The arrows indicate dCD34+CD56− cells. V marks the CD34+CD56− decidual vessels. (Magnification: 40×.)

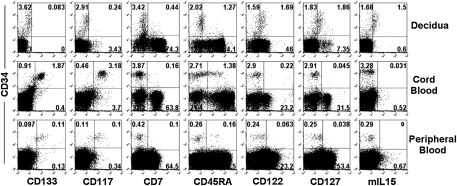

By using flow cytometry, we further analyzed dCD34+VEGF-R2− cells in comparison with CB CD34+ or PB CD34+ cells for a panel of informative surface markers (Fig. 2). In particular, dCD34+ cells express neither CD133 nor CD117 (also known as c-kit). In contrast, CB and PB CD34+ cells express both these molecules. CD45RA displays a homogeneous dull expression in dCD34+ cells, whereas it is present in only a fraction of CB CD34+ cells. Remarkably, decidua cells displaying a bright surface expression of CD34 antigen express CD122, CD127, and membrane-bound IL-15 (mIL-15), which are absent in CD34bright cells isolated from the other sources analyzed. As these receptors/markers are typical of NK cell precursors in which they mediate the response to IL-15, these data suggest that dCD34bright (i.e., VEGF-R2−) cells are committed to the NK cell lineage (38, 41, 42).

Fig. 2.

Comparative analysis of informative surface markers expressed by CD34+ cells isolated from human decidua, CB cells, and PB cells. We analyzed mononuclear cell suspensions freshly isolated from decidua, CB cells, or PB cells for the coexpression of CD34 and the indicated surface antigens. Representative experiment among 10 experiments.

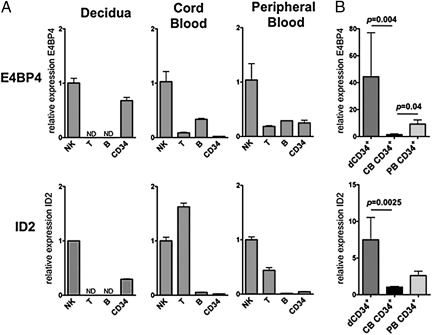

Expression of E4BP4 and ID2 by dCD34+ Cells.

Previous studies in mice indicated that the transcription factors E4BP4 (also known as NFIL3) and ID2 play an essential role in NK cell development from BM-derived CD34+ cells (43–47). In addition, the expression of ID2 has been documented in human NK cells differentiating from CB CD34+ cells (48). Recent data revealed that E4BP4 is also present in human NK cell precursors (49). We analyzed the mRNA levels of E4BP4 and ID2 in different human lymphoid populations isolated from decidua, CB, and PB. NK cells isolated from all sources display high levels of E4BP4 mRNA compared with T and B lymphocytes (Fig. 3A). Notably, the E4BP4 mRNA content in dCD34+ cells is comparable to that detectable in mature dNK cells. T cells express ID2, but not E4BP4, mRNA, whereas B cells are virtually negative for ID2 and contain low levels of E4BP4 mRNA. Thus, also in human lymphoid populations, E4BP4 appears to be mostly confined to NK cells. dCD34+ cells express much more E4BP4 (P = 0.004) and ID2 mRNA (P = 0.0025) than CB CD34+ cells do (Fig. 3B). These data further support the notion that dCD34+ cells are committed toward the NK cell lineage.

Fig. 3.

Human dCD34+ cells express E4BP4 and ID2 transcription factors. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of E4BP4 and ID2 in lymphoid populations and CD34+ cells isolated from decidua, CB cells, or PB cells. For each group of cells, we calculated sample relative expression on the basis of the expression level detected in NK cells, arbitrarily normalized to 1. Data were obtained from three independent experiments. N.D., not determined. (B) Comparative analysis of E4BP4 and ID2 expression levels in CD34+ cells isolated from decidua, CB cells, or PB cells. For each group of cells, we calculated sample relative expression on the basis of the expression level detected in CB CD34+ cells, arbitrarily normalized to 1. Data were obtained from six independent experiments. In each of these six experiments, all different samples were pool obtained from two different donors. In all experiments (A and B), all samples were run in triplicate and we normalized gene expression levels to GAPDH mRNA and performed relative quantification by ΔΔCT method. P values were obtained by two tailed Mann–Whitney t test.

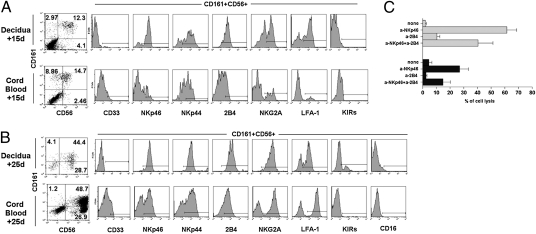

dCD34+ Cells Differentiate into KIR+ Mature NK Cells.

As decidua contains NK cells with a peculiar surface phenotype (CD56brightCD16−KIR+/−) and dCD34+ cells express markers that suggest their NK cell commitment, we asked the question of whether dNK cells could originate from CD34+ cells present in the decidua (11). To this end, we compared dCD34+ and CB CD34+ cells for their ability to undergo in vitro differentiation toward NK cells, in medium supplemented with stem cell factor, FMS-like tyrosine kinase ligand, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 (referred to as cytokine mix). After 15 d of culture, both dCD34+ and CB CD34+ cells gave rise to cells coexpressing CD161 and CD56 (Fig. 4A). These cells were further analyzed for other informative surface antigens. These included the myeloid marker CD33, the NK receptors NKp46, NKp44, 2B4 (CD244), NKG2A, and KIRs, and the adhesion molecule LFA-1. Cells derived from dCD34+ precursors were CD33− and in large proportions NKp46+, NKp44+, and 2B4+. Both NKG2A and LFA-1 displayed a bimodal distribution of fluorescence with a prevalence of positive cells. At this time point, no KIR expression could be detected. At variance, a minority of CB CD34+-derived CD161+CD56+ cells displayed a dull expression of CD33. The NKp46 activating receptor was present only on a fraction of cells and displayed a bimodal distribution of fluorescence. Most cells were NKp44+ and 2B4+, whereas only a small subset were NKG2A+ or LFA-1+; NKp30- and NKG2D-activating receptors displayed a similar pattern of surface expression (Fig. S1). In contrast, KIRs were not detectable. Taken together, these data indicate that dCD34+ cells, cultured in cytokine mix, differentiate more rapidly than CB CD34+ cells toward NK cells. However, at this time point (15 d of culture), the bimodal distribution of NKG2A and the absence of KIRs revealed an immature stage of NK cell differentiation (38). We analyzed the same dCD34+- and CB CD34+-derived cells at a later time interval, i.e., at day 25 of culture (Fig. 4B). At this time point, CD161+CD56+ cells largely outnumbered the negative cell fractions. Gated CD161+CD56+ cells, derived both from dCD34+ and CB CD34+ cells, expressed NKp46, NKp44, 2B4, NKG2A, and LFA-1 on the majority of cells. Notably, they did not express CD16, whereas only dCD34+-derived cells displayed a sizable fraction of KIR+ cells. Taken together, these data indicate that dCD34+ cells may undergo differentiation toward CD16−KIR+ dNK-like cells after a relatively short time interval of culture.

Fig. 4.

Human dCD34+ cells undergo in vitro differentiation into mature NK cells in the presence of appropriate cytokines and express functional receptors. Purified CD34+ cells isolated from decidua or CB cells were cultured in the presence of cytokine mix and were analyzed at the indicated time intervals. (A) Shows the proportion of cells stained for CD161 and CD56 after 15 d of culture. CD161+CD56+ cells were gated and analyzed for the expression of the indicated surface markers. (B) We performed similar analysis on the same samples at day 25 of culture. In this experiment the KIR detected was KIR2DL2/3. Representative experiment among 10 experiments. (C) At day 15 of culture, NK cells derived from dCD34+ (gray bars) or CB CD34+ (black bars) cells were analyzed for NK receptor-mediated cytotoxicity in a redirected killing assay against the FcR+γ P815 target cells. NKp46- or 2B4-specific mAbs were used. The effector-to-target ratio (5/1) was calculated on the basis of the percentage of CD161+CD56+ NK cells. Data are expressed as a mean percentage ± SEM of target cell lysis obtained in three independent experiments.

We also investigated the functional capability of the surface NK receptors expressed by NK cells derived from dCD34+ cells. In particular, we analyze, at day 15 of culture, NKp46 and 2B4, two receptors present in virtually all CD161+CD56+ cells at this time point. To this end, we performed comparative analysis of the cytolytic activity induced by NKp46- or 2B4-specific mAbs in dCD34+- or CB CD34+-derived NK cells by a redirected killing assay (Fig. 4C). NKp46-specific mAb induced strong target cell lysis, whereas 2B4-specific mAb did not. Moreover, 2B4-specific mAb partially inhibited NKp46-induced cytolysis. Notably, the inhibitory form of 2B4 is correlated with the lack of expression of the cytoplasmic signaling lymphocyte activation molecule-associated protein. This condition is typical of the early stages of NK cell differentiation (from BM and CB precursors) but also of mature dNK cells as previously described (13, 23, 24).

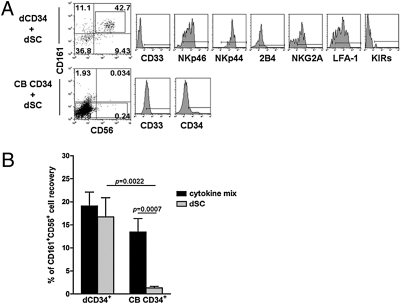

dSCs Induce Differentiation of dCD34+ into NK Cells in the Absence of Cytokines.

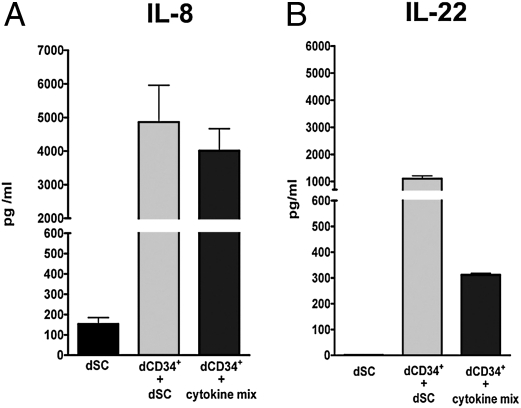

Because the decidual microenvironment—the site where differentiation of dCD34+ cells into NK lymphocytes would occur—is rich in stromal cells (i.e., dSCs), we further investigated whether dSCs could exert a promoting effect on differentiation. To this end, we performed cocultures of dCD34+ or CB CD34+ cells with dSCs for different time intervals in the absence of the cytokine mix. Controls included CD34+ cells cultured with the cytokine mix. dCD34+ cells, cocultured with dSCs for 15 d, could undergo differentiation into CD161+CD56+ cells, most of which expressed NKp46, NKp44, 2B4, NKG2A, and LFA-1 (Fig. 5A). In contrast, CB CD34+ cells, cultured under the same conditions with dSCs, remained viable but did not acquire NK cell markers, whereas they partially maintained CD34 and expressed CD33 antigen. These results indicate that the interaction of dCD34+ cells with dSCs is sufficient to induce dCD34+ differentiation into NK cells. We obtained similar results in 10 independent experiments, and the data were statistically significant (Fig. 5B). As a unique functional property of freshly isolated dNK cells is the production of high amounts of IL-8 (15), we investigated whether dCD34+-derived NK cells produced IL-8 (Fig. 6). dCD34+-derived NK cells cultured in the presence of cytokine or cocultured with dSC released high levels of IL-8 in their culture supernatants. In addition, these developing NK cells released IL-22 (Fig. 6), a cytokine associated with an immature stage of NK cell differentiation, and express RAR-related orphan receptor C (RORC) transcription factor (Fig. S2) (49, 50). Notably, in cultures supplemented with cytokine mix, the amounts of IL-22 released in the supernatants was lower, possibly reflecting a more advanced stage of NK cell differentiation, as described earlier (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5.

Human dCD34+ cells differentiate into NK cells when cocultured with dSCs. We cultured purified CD34+ cells isolated from decidua or CB cells together with adherent dSCs in the absence of exogenous cytokines. (A) After 15 d, nonadherent cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for the expression of CD161 and CD56. CD161+CD56+ cells derived from dCD34+ cells were further assessed for the indicated markers. We could not detect CD161+CD56+ cells in cells derived from CB CD34+ precursors; thus, we analyzed them for the expression of CD34 and CD33 markers. Representative experiment among 10 experiments. (B) We cultured purified CD34+ cells isolated from decidua or CB cells with dSCs or cytokine mix. At day 15 of culture, we analyzed cells for the expression of CD161 and CD56 markers. Data refer to the mean percentage ± SEM of CD161+CD56+ cells recovered in 10 independent experiments. P values were obtained by two-tailed Mann–Whitney t test.

Fig. 6.

Human NK cells derived from dCD34+ cells produce high amounts of IL-8 and IL-22. dCD34+ cells were cultured for 15 d in the presence of cytokine mix or dSCs. Supernatants were analyzed for the presence of IL-8 (A) and IL-22 (B). Supernatants obtained from dSCs cultured alone were used as controls. Data are expressed as concentration of IL-8 or IL-22 ± SEM (in pg/mL) obtained in three independent experiments.

We further analyzed whether dCD34+ cells would retain the capability of differentiating toward myeloid cells in the presence of GM-CSF. As shown in Fig. S3, dCD34+ cells failed to differentiate into CD33+CD14+ cells, whereas CB CD34+ cells acquired both myeloid markers.

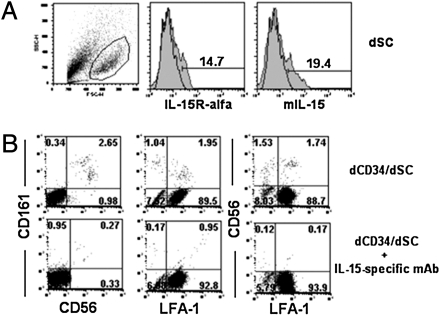

dSC-Induced Differentiation of dCD34+ Cells into NK Cells Involves mIL-15.

Given the dSC capability of inducing NK cell differentiation from dCD34+ cells, we investigated possible molecular interactions involved in this process. As illustrated earlier, dCD34+ cells express CD122 able to bind mIL-15. Thus, we analyzed whether dSCs expressed mIL-15 and IL-15Rα chain (41, 42). Indeed, staining with mIL-15, as well as with IL-15Rα–specific mAbs, revealed that a fraction of dSCs expressed these molecules, suggesting the possibility of an effective functional interaction between dSCs and dCD34+CD122+ cells (Fig. 7A). To explore this possibility, dCD34+ cells were cocultured for 8 d with dSCs in the presence or absence of a neutralizing IL-15–specific mAb. We could not detect CD161+CD56+ NK cells in the presence of IL-15–specific mAb (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Expression of mIL-15 by human dSCs and its functional role in dSC-mediated dCD34+ differentiation into NK cells. (A) We analyzed the dSC populations obtained from decidua for the surface expression of IL-15Rα and mIL-15. (B) We cultured purified dCD34+ cells for 8 d with dSCs in the presence of an IL-15–specific neutralizing mAb or an isotype-matched control mAb. We analyzed cells for the expression of CD161, CD56, and LFA-1 antigens.

Discussion

In this study we show that CD34+ cells are present in human decidua, where they represent a sizable fraction of mononuclear cells. Their surface phenotype, together with the expression of E4BP4 and ID2 transcription factors, suggested their commitment toward the NK cell lineage. Indeed, they could undergo in vitro differentiation toward mature NK cells not only in the presence of suitable cytokines but also upon coculture with decidua-derived stromal cells.

During the first trimester of pregnancy, NK cells represent the majority of the total mononuclear cells in human decidua and display unique phenotypic and functional properties (11–17). A possible explanation is that dNK cells derive from PB NK cells and acquire their unique features as the result of the particular decidual microenvironment (including cytokines, hormones, and cell-to-cell contacts). Another explanation is that they may derive from precursors present in the decidua (notably, these explanations do not exclude each other). Our present finding would favor the second hypothesis: thus, CD34+ precursors would populate the human decidua, where they could represent the main source of dNK cells. In agreement with this concept, dCD34+ cells freshly isolated from decidual tissues appear to be committed toward the NK cell lineage, as they express the IL-15/IL-2R common β chain (CD122), the IL-7Rα chain (CD127), and mIL-15, whereas they lack CD133, a typical marker of stem cells (38, 41, 42). The expression of high mRNA levels for E4BP4 and ID2 is in line with their NK cell commitment. In mice, these transcription factors are associated with the NK cell lineage (43–47). Analysis of human mononuclear cells derived from decidua, CB, and PB shows that E4BP4 is selectively expressed by mature NK cells. These data confirm a recent report (49) and provide further evidence that E4BP4 is NK-specific. While our present study was under review, an interesting report provided evidence in mice that the transcription factor TOX plays a role in murine NK cell differentiation (50). Experiments of in vitro NK cell differentiation confirmed that dCD34+ cells represent precursors of dNK cells. Thus, dCD34+ cells could differentiate into NK cells after a relatively short culture interval, compared with CB CD34+ cells. In addition, similar to dNK cells, they acquire KIRs, express a number of functional receptors, and produce large amounts of IL-8 and IL-22 (11–15, 51). That dCD34+ cells are indeed committed toward NK cells is confirmed by the finding that they failed to differentiate into cells of myeloid lineage in the presence of GM-CSF.

A relevant question was whether cells of the decidual microenvironment could also sustain NK cell differentiation from dCD34+ cells in the absence of exogenous cytokines. dSCs represented a possible candidate because they are a major component of the decidual tissue and express mIL-15 and IL-15Rα, which may signal dCD34+ cells via CD122 (41, 42). Indeed, coculture of dSC with dCD34+ cells resulted in NK cell differentiation in the absence of exogenous cytokines. This property appeared to be unique to dCD34+ cells, as CB CD34+ cells did not differentiate into NK cells when cocultured with dSC alone. Therefore, the specific interaction between (NK-committed) dCD34+ cells and dSCs appears to be sufficient to promote NK cell differentiation. Experiments using IL-15–neutralizing mAb suggest that this cytokine may play a role in the dSC-induced differentiation of dCD34+ cells into mature NK cells. Our data support the notion that at least a fraction of dNK cells might directly derive from CD34+ cells present in the decidua. They also suggest that both expression of E4BP4 and NK commitment may be acquired in the decidua as a result of their interaction with dSCs. It is conceivable that the IL-15/IL-15R interaction occurring between dSC and dCD34+ cells may induce the expression of E4BP4 mRNA in dCD34+ cells. In this context, studies in mice showed that E4BP4 may act downstream of IL15-R during NK cell differentiation (46).

Recently, it has been proposed that dNK cells may derive from immature endometrial NK cells upon sequential steps of differentiation and exposure to IL-15 at the beginning of pregnancy (39). In this context, it has been reported that the endometrial tissue may contain CD34+CD45+ HPCs (52). NK-committed CD34+ cells were also identified in human LNs, tonsils, and intestinal lamina propria, although these precursors displayed a different pattern of marker expression (36–38, 53). For example, in LN they expressed the β7 integrin (36) that was absent in dCD34+ cells. The presence of NK-committed CD34+ cells is in agreement with our present findings and also suggests that NK cells of certain peripheral districts may derive, at least in part, from CD34+ precursors undergoing in situ differentiation.

In conclusion, dNK cells represent the major lymphoid population present in the decidua during the first trimester of pregnancy and play a functional role in inducing tissue remodeling and neoangiogenesis (15–17). In addition, they contribute to the induction of regulatory T cells that modulate the maternal physiologic immune response, thus preventing fetal rejection (18–20). Our present evidence that CD34+ cells exist in the decidua, where they undergo differentiation toward NK cells, offers important clues for a better understanding of major physiological mechanisms occurring in the early phases of pregnancy. It is possible to speculate that defective CD34+ cell migration to decidua and/or differentiation into mature NK cells with peculiar functional capabilities may have relevant consequences on successful pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Culture of CD34+ Cells and dSCs.

We obtained decidua samples at 9 to 12 wk of gestation from singleton pregnancies of mothers requesting termination of the pregnancy for social reasons. We isolated decidual cell suspensions as previously described (20). CB samples were provided by Liguria Cord Blood Bank. We isolated CB and PB mononuclear cells as previously described (3, 24). The relevant institutional review boards approved the study and all patients gave their written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Detailed methods are included in SI Materials and Methods.

mAbs and FACS Staining.

Cells were preincubated with human IgG (Baxter). We performed two-, three-, and four-color cytofluorimetric analysis on a FACSCalibur device (BD Biosciences). Analyses were performed on PI-negative or 7AAD-negative gated cells. We analyzed data by FlowJo software. FACS sorting was performed on FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Post-sort analysis showed more than 98% purity. The complete list of mAbs used in our experiments is included in SI Materials and Methods.

Immunohistochemical Analysis.

Detailed methods are included in SI Materials and Methods.

Cytolytic Assay.

Detailed methods are included in SI Materials and Methods.

Analysis of Cytokine Release.

Detailed methods are included in SI Materials and Methods.

Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis.

Primer sequences and detailed methods are included in SI Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

We performed a two-tailed Mann–Whitney t test for all statistical analyses; P values of 0.05 or lower were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Reverberi and F. Loiacono for help in cell sorting and P. L. Venturini and A. Bo for sample selection. P.V. is a recipient of a fellowship awarded by Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro. This work was supported by grants awarded by Special Project 5×1000 from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro; Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR), Fondo Investimenti Ricerca di Base (FIRB), and Progetti Ricerca Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) Grants MIUR-FIRB 2003 project RBLA039LSF-001/003, MIUR-PRIN 2008 project prot. 2008PTB3HC_005 (to L.M.); Ministero della Salute Grant RF2006-Ricerca Oncologica–Project of Integrated Program 2006-08, agreements n. Ricerca Oncologica, strategici 3/07 (to L.M.); and MIUR-PRIN 2007 Project 20077NFBH8_005 and Ministero della Salute Progetto Strategico, RFPS-2007-4-633146 agreement RO Strategici 8/07 (to M.C.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1016257108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 2008;112:461–469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cells, viruses and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:41–49. doi: 10.1038/35095564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sivori S, et al. CpG and double-stranded RNA trigger human NK cells by Toll-like receptors: Induction of cytokine release and cytotoxicity against tumors and dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10116–10121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403744101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcenaro E, Ferranti B, Falco M, Moretta L, Moretta A. Human NK cells directly recognize Mycobacterium bovis via TLR2 and acquire the ability to kill monocyte-derived DC. Int Immunol. 2008;20:1155–1167. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moretta A, et al. Receptors for HLA class-I molecules in human natural killer cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:619–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long EO. Regulation of immune responses through inhibitory receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:875–904. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moretta A, et al. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moretta L, Moretta A. Unravelling natural killer cell function: Triggering and inhibitory human NK receptors. EMBO J. 2004;23:255–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agaugué S, Marcenaro E, Ferranti B, Moretta L, Moretta A. Human natural killer cells exposed to IL-2, IL-12, IL-18, or IL-4 differently modulate priming of naive T cells by monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;112:1776–1783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-135871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scordamaglia F, et al. Perturbations of natural killer cell regulatory functions in respiratory allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moffett-King A. Natural killer cells and pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:656–663. doi: 10.1038/nri886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keskin DB, et al. TGFbeta promotes conversion of CD16+ peripheral blood NK cells into CD16- NK cells with similarities to decidual NK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3378–3383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611098104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vacca P, et al. Analysis of natural killer cells isolated from human decidua: Evidence that 2B4 (CD244) functions as an inhibitory receptor and blocks NK-cell function. Blood. 2006;108:4078–4085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponte M, et al. Inhibitory receptors sensing HLA-G1 molecules in pregnancy: Decidua-associated natural killer cells express LIR-1 and CD94/NKG2A and acquire p49, an HLA-G1-specific receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5674–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanna J, et al. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006;12:1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Bouteiller P, Tabiasco J. Killers become builders during pregnancy. Nat Med. 2006;12:991–992. doi: 10.1038/nm0906-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vacca P, et al. Regulatory role of NKp44, NKp46, DNAM-1 and NKG2D receptors in the interaction between NK cells and trophoblast cells. Evidence for divergent functional profiles of decidual versus peripheral NK cells. Int Immunol. 2008;20:1395–1405. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heikkinen J, Möttönen M, Alanen A, Lassila O. Phenotypic characterization of regulatory T cells in the human decidua. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:373–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vacca P, et al. Crosstalk between decidual NK and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells results in induction of Tregs and immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11918–11923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001749107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mrózek E, Anderson P, Caligiuri MA. Role of interleukin-15 in the development of human CD56+ natural killer cells from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;87:2632–2640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller JS, McCullar V. Human natural killer cells with polyclonal lectin and immunoglobulinlike receptors develop from single hematopoietic stem cells with preferential expression of NKG2A and KIR2DL2/L3/S2. Blood. 2001;98:705–713. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivori S, et al. Early expression of triggering receptors and regulatory role of 2B4 in human natural killer cell precursors undergoing in vitro differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4526–4531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072065999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vitale C, Cottalasso F, Montaldo E, Moretta L, Mingari MC. Methylprednisolone induces preferential and rapid differentiation of CD34+ cord blood precursors toward NK cells. Int Immunol. 2008;20:565–575. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shilling HG, et al. Reconstitution of NK cell receptor repertoire following HLA-matched hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;101:3730–3740. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vitale C, et al. Analysis of the activating receptors and cytolytic function of human natural killer cells undergoing in vivo differentiation after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:455–460. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grzywacz B, et al. Coordinated acquisition of inhibitory and activating receptors and functional properties by developing human natural killer cells. Blood. 2006;108:3824–3833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-020198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H, Nakauchi H. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graf T. Differentiation plasticity of hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2002;99:3089–3101. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kondo M, et al. Biology of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors: implications for clinical application. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:759–806. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shizuru JA, Negrin RS, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells: clinical and preclinical regeneration of the hematolymphoid system. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:509–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mingari MC, et al. In vitro proliferation and cloning of CD3- CD16+ cells from human thymocyte precursors. J Exp Med. 1991;174:21–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mingari MC, et al. Interleukin-15-induced maturation of human natural killer cells from early thymic precursors: Selective expression of CD94/NKG2-A as the only HLA class I-specific inhibitory receptor. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1374–1380. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Márquez C, et al. Identification of a common developmental pathway for thymic natural killer cells and dendritic cells. Blood. 1998;91:2760–2771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalloul AH, et al. Functional and phenotypic analysis of thymic CD34+CD1a- progenitor-derived dendritic cells: Predominance of CD1a+ differentiation pathway. J Immunol. 1999;162:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freud AG, et al. A human CD34(+) subset resides in lymph nodes and differentiates into CD56bright natural killer cells. Immunity. 2005;22:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freud AG, et al. Evidence for discrete stages of human natural killer cell differentiation in vivo. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1033–1043. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freud AG, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cell development. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manaster I, et al. Endometrial NK cells are special immature cells that await pregnancy. J Immunol. 2008;181:1869–1876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plaisier M, et al. Decidual vascularization and the expression of angiogenic growth factors and proteases in first trimester spontaneous abortions. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:185–197. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briard D, Brouty-Boyé D, Azzarone B, Jasmin C. Fibroblasts from human spleen regulate NK cell differentiation from blood CD34(+) progenitors via cell surface IL-15. J Immunol. 2002;168:4326–4332. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giron-Michel J, et al. Membrane-bound and soluble IL-15/IL-15Ralpha complexes display differential signaling and functions on human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2005;106:2302–2310. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yokota Y, et al. Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Nature. 1999;397:702–706. doi: 10.1038/17812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boos MD, Yokota Y, Eberl G, Kee BL. Mature natural killer cell and lymphoid tissue-inducing cell development requires Id2-mediated suppression of E protein activity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1119–1130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Graf T. Determinants of lymphoid-myeloid lineage diversification. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:705–738. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gascoyne DM, et al. The basic leucine zipper transcription factor E4BP4 is essential for natural killer cell development. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1118–1124. doi: 10.1038/ni.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamizono S, et al. Nfil3/E4bp4 is required for the development and maturation of NK cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2977–2986. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonanno G, et al. Interleukin-21 induces the differentiation of human umbilical cord blood CD34-lineage- cells into pseudomature lytic NK cells. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hughes T, et al. Interleukin-1beta selectively expands and sustains interleukin-22+ immature human natural killer cells in secondary lymphoid tissue. Immunity. 2010;32:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aliahmad P, de la Torre B, Kaye J. Shared dependence on the DNA-binding factor TOX for the development of lymphoid tissue-inducer cell and NK cell lineages. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:945–952. doi: 10.1038/ni.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Male V, et al. Immature NK cells, capable of producing IL-22, are present in human uterine mucosa. J Immunol. 2010;185:3913–3918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lynch L, Golden-Mason L, Eogan M, O'Herlihy C, O'Farrelly C. Cells with haematopoietic stem cell phenotype in adult human endometrium: Relevance to infertility? Hum Reprod. 2007;22:919–926. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chinen H, et al. Lamina propria c-kit+ immune precursors reside in human adult intestine and differentiate into natural killer cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:559–573. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.