Abstract

Hox genes encode transcription factors widely used for diversifying animal body plans in development and evolution. To achieve functional specificity, Hox proteins associate with PBC class proteins, Pre-B cell leukemia homeobox (Pbx) in vertebrates, and Extradenticle (Exd) in Drosophila, and were thought to use a unique hexapeptide-dependent generic mode of interaction. Recent findings, however, revealed the existence of an alternative, UbdA-dependent paralog-specific interaction mode providing diversity in Hox–PBC interactions. In this study, we investigated the basis for the selection of one of these two Hox–PBC interaction modes. Using naturally occurring variations and mutations in the Drosophila Ultrabithorax protein, we found that the linker region, a short domain separating the hexapeptide from the homeodomain, promotes an interaction mediated by the UbdA domain in a context-dependent manner. While using a UbdA-dependent interaction for the repression of the limb-promoting gene Distalless, interaction with Exd during segment-identity specification still relies on the hexapeptide motif. We further show that distinctly assembled Hox–PBC complexes display subtle but distinct repressive activities. These findings identify Hox–PBC interaction as a template for subtle regulation of Hox protein activity that may have played a major role in the diversification of Hox protein function in development and evolution.

Keywords: transcriptional regulation, AbdominalA, Hox protein specificity and diversity

Hox genes encode transcription factors widely used for diversifying animal body plans in development and evolution (1). Functional diversity likely relies on interaction with protein partners (2, 3). Although other proteins presumably are involved, our current knowledge of Hox protein mode of action stems mainly from the interaction with PBC class of cofactors, Pbx in vertebrates and Extradenticle (Exd) in Drosophila (4–7). Extensive data, including in vitro interaction assays (8, 9), the requirement for in vivo Exd-dependent processes (10–12), and crystallographic studies (13–16), support the notion that Hox–PBC interaction relies on a short hexapeptide (HX) motif lying upstream of the homeodomain (HD) and shared by most Hox proteins.

However, some PBC-dependent Hox functions are retained following mutation of the HX motif. This retention is illustrated in vertebrates by the dominant phenotypes resulting from HX mutation of the mouse HoxB-8 protein, which are difficult to reconcile with a lack of Pbx protein interaction (17), and in Drosophila by the retained capacity of HX-mutated AbdominalA (AbdA) and Ultrabithorax (Ubx) proteins to repress the limb-promoting target gene Distalless (Dll) (11, 18). In Ubx, a short motif located downstream of the HD conveys Exd interaction potential (18). This motif, UbdA, 8 aa long, is shared exclusively by the central paralog proteins Ubx and AbdA and is found only in protostomes (19, 20).

Thus, Hox–PBC interactions occur through distinct modes, suggesting that flexibility in Hox–PBC contacts contributes in specifying and diversifying Hox protein function and raising questions about the mechanisms controlling such flexibility. In this study, we use Dll regulation and naturally occurring variations in Ubx protein sequences during development and evolution to investigate the molecular control of Hox–PBC interaction and to evaluate its functional impact.

Results

Arthropod Ubx Proteins Display Distinct Exd Interaction Modes for Dll Repression.

Alignment of available Ubx sequences representative of the four main arthropod groups, chelicerates (Cupiennius salei; Cs), myriapods (Strigamia maritima; Stm), crustaceans (Artemia franciscana; Af), and hexapods (Drosophila melanogaster; Dm), shows conserved HX and UbdA motifs, indicating the potential for both Hox–Exd interaction modes (Fig. 1A). Significant sequence divergences are found outside the HD, including four protein domains absent in non-Drosophila Ubx proteins (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Distinct modes of Exd interaction in arthropod Ubx proteins. (A) Alignment of Ubx peptides (HX to UbdA sequences) from C. salei, S. maritima, A. franciscana, and D. melanogaster UbxIa and IVa isoforms. (B) EMSA of Af-Ubx, Stm-Ubx, Cs-Ubx, and Dm-UbxIa variants, wild type or mutated in the HX or UbdA motifs on the DllR probe. Lanes 1 and 2: DllR probe alone and in the presence of a fixed amount of Exd and Hth; lanes 3–26: fixed amount of Exd, Hth, and a fixed, identical amount of Af-Ubx, Stm-Ubx, or Cs-Ubx variants. Bars above the gel indicate proteins present in the experiment. (C) (Left) Repressive potentials in Drosophila of Cs-Ubx variants. The arm-Gal4–driven ubiquitous expressions of the variants (red) repress the Dll reporter gene (green) to different extents. (Right) Quantifications of Dll reporter repression. The error bars represent SDs; the number above the bracket indicates the P value.

To investigate whether these sequence divergences could affect the mode of Hox–Exd association, we performed in vitro band shift experiments, in which trimeric Ubx/Exd/Homothorax (Hth) complex formation on Dll target sequences relies on Ubx–Exd interaction (18, 21). Mutations of either the HX or UbdA motifs were introduced in Ubx sequences. Although Dm-Ubx (more specifically the Dm-UbxIa isoform, see below) requires the UbdA motif to assemble a Ubx/Exd/Hth complex in vitro (18), Exd interaction by Cs-Ubx, Af-Ubx (22), and Stm-Ubx (23) implicates the HX motif instead (Fig. 1B). We concluded that sequence divergences between Drosophila and other arthropod Ubx proteins underlie distinct Exd interaction modes on the Dll target sequence.

In the Drosophila embryo, Dll expression is restricted to thoracic segments and is repressed in abdominal segments by Ubx (24) and AbdA (25). Accordingly, ectopic expression of Ubx (or AbdA) in thoracic segments represses Dll expression in thoracic segments (24, 26, 27). Chelicerates, like insects, possess a reduced number of legs; myriapods and crustaceans bear more legs (28). However, Ubx/AbdA expression domains do not account for changes in leg number, and changes in protein activity underlie the control of leg suppression in crustaceans (25). If such changes also underlie the control of leg suppression in chelicerates and myriapods, Cs-Ubx, but not Stm-Ubx, should display leg-suppressive potential. Because our final aim is to evaluate how protein domains contribute to leg suppression (not possible at present in chelicerates and myriapods), we evaluated the leg-repressive potential of arthropod Ubx proteins by quantifying their repressive ability on the limb-promoting gene Dll enhancer [followed by the DME-lacZ reporter (24)] in the Drosophila embryo. For quantitation, we established experimental conditions to drive transgene expression of Ubx variants close to physiological levels of Drosophila Ubx (Experimental Procedures and Fig. S2). Although Stm-Ubx and Af-Ubx are poorly active in this assay (respectively 25% and 30% repression, respectively), Cs-Ubx acts as a more potent repressor (60% repression; Fig. S3).

The repressive potential of Cs-Ubx allows us to investigate whether the distinctive Exd interaction modes seen in vitro apply also to the Exd-dependent in vivo repression of the Hox target gene Dll (24, 26, 27). Transgenic lines allowing thoracic expression of HX- or UbdA-mutated forms of Cs-Ubx were generated. Consistent with in vitro observations, HX mutation severely affects the repressive activity of Cs-Ubx, but UbdA mutation has no effect (Fig. 1C). Thus, Cs-Ubx and Dm-Ubx both interact with Exd to repress Dll but act through distinct protein motifs, HX and UbdA, respectively. This observation indicates that the sequence divergences between Cs-Ubx and Dm-Ubx are responsible for selecting distinct Ubx/Exd interaction modes.

Linker Region Extension Promotes an UbdA-Dependent Interaction Mode for Dll Repression.

Among the four predominant sequence divergences distinguishing Drosophila from other arthropod Ubx proteins, we focused on the domain that separates the HX from the HD, referred to as the “linker region” (LR). Notably, the Drosophila Ubx gene encodes several splice variants that are evolutionary conserved in the Drosophila lineage (29, 30). These isoforms differ only in the size of the LR. The most abundant isoform, Ia, has an LR that is 41 aa long and is expressed in the ectoderm where Dll is repressed (31). With the exception of Ib, other isoforms have a smaller LR, intermediate in size between the Drosophila Ia isoform and other arthropod Ubx proteins, which all have an LR 7 aa long. Such Ubx isoforms, differing in the LR, were not found in non-Drosophila arthropods, suggesting either that they do not exist or that proper strategies for recovering them were not employed.

To address the role of the LR in the choice of Exd interaction mode, the HX or UbdA motifs were mutated in the IVa, IVb, and IIb isoforms, displaying LRs of 7, 16, and 33 aa, respectively. In vitro band shift experiments on the Dll regulatory sequence show a progressive transition from the HX to the UbdA interaction mode that correlates with the extent of LR extension in the different isoforms (see Fig. 2A for isoforms Ia and IVa and Fig. S4 for all isoforms).

Fig. 2.

Drosophila UbxIa and -IVa isoforms repress Dll using different Exd interaction modes. (A) EMSA of Dm-UbxIVa variants, wild type or mutated, in the HX or UbdA motifs on the DllR probe. Lanes 1 and 2: DllR probe alone and in the presence of fixed amount of Exd and Hth. Lanes 3–8: fixed amount of Exd, Hth, and fixed, identical amount of Dm-UbxIVa variants. Bars above the gel indicate proteins present in the experiment. (B) Repressive potentials of Dm-UbxIa and Dm-UbxIVa variants. (Left) armadillo(arm)-Gal4–driven ubiquitous expression of the variants (red) represses the Dll reporter gene (green) to different extents. (Right) Quantifications of Dll reporter repression. The error bars represent SDs; numbers above the brackets indicate P values.

To gain in vivo evidence for a role of LR extension in selecting a UbdA-mediated Exd interaction mode, we analyzed the Dll repressive potential of HX and UbdA variants of the UbxIVa isoform. We observed, as previously reported (24, 26, 27), that Dm-UbxIVa had a weaker Dll repressive potential than Dm-UbxIa (45% vs. 85%) (Fig. 2B). Mutation of Exd-interacting motifs in Dm-UbxIVa revealed that the HX, and not the UbdA motif as in UbxIa, is essential for Exd-dependent Dll repression (Fig. 2B). Because the only sequence difference between Dm-UbxIa and Dm-UbxIVa is the LR, we concluded that LR extension promotes a UbdA-mediated Exd interaction mode in Dm-Ubx proteins. LR extension may influence the mode of Exd interaction by modifying the length of the LR (in the folded protein) and/or by providing specific sequence motifs promoting the UbdA interaction mode.

Linker Region Extension During Arthropod Evolution Is Responsible for Distinct Mode of Dll Repression.

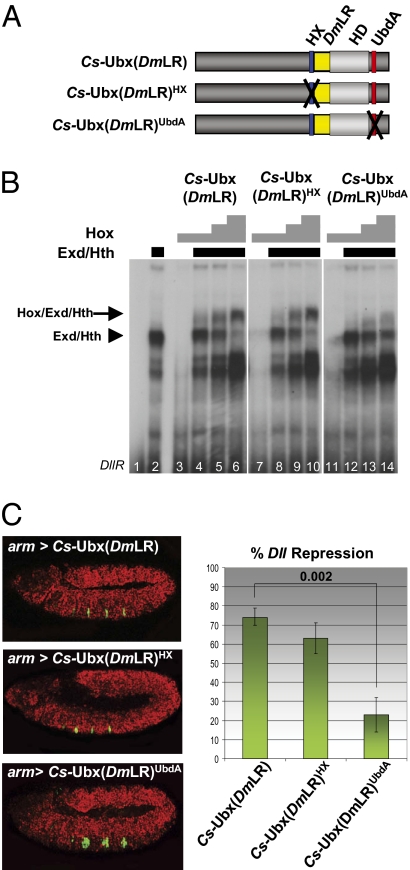

The distinct Exd interaction modes seen for Dm-UbxIa and Dm-UbxIVa isoforms suggest that, among the differences accumulated in Ubx protein sequences during arthropod evolution (Fig. S1), those regarding the LR may be responsible for changing the Exd interaction mode. To address this possibility, we generated Drosophila/Cupiennius chimeric proteins where the Cupiennius LR was replaced by the extended Drosophila LR (DmLR) (Fig. 3A). We first analyzed the capacity of such a chimeric protein, intact or mutated in either the HX or UbdA motifs, to interact with Exd on the Dll target sequence in vitro. Results showed that grafting the Drosophila LR affects the Exd interaction mode, because the chimeric Cs-Ubx(DmLR) requires the UbdA motif and not the HX motif to assemble the tripartite Ubx/Exd/Hth complex (Fig. 3B and Fig. S5). We next established transgenic lines allowing expression of these Drosophila/Cupiennius chimeric proteins in the fly embryo. Our analysis established that changes in motif requirement for Exd interaction also are observed in vivo, because Exd-dependent Dll repression by Cs-Ubx(DmLR) is severely affected by mutation of the UbdA motif but not by mutation of the HX motif (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Evolutionary LR extension promotes UbdA-mediated Exd interaction by Ubx for Dll repression. (A) Schematic representation of Cs-Ubx variants, with Dm-Ubx LR insertion (yellow) and motif mutations indicated by black crosses. (B) EMSA of Cs-Ubx variants on the DllR probe. Lane 1: DllR probe alone; lanes 2–12: fixed amount of Exd and Hth and increasing identical amounts of Cs-Ubx variants, as indicated. Bars above the gel indicate the amount of protein present in the experiment. (C) (Left) Repressive potentials in Drosophila of Cs-Ubx(DmLR) variants. arm-Gal4–driven ubiquitous expression of the variants (red) represses the Dll reporter gene (green) to different extents. (Right) Quantifications of Dll reporter repression. The error bars represent SDs; the number above the bracket indicates the P value.

The role of the LR in the selection of the Exd interaction mode also was addressed in the context of the AbdA protein. Cs-AbdA has a shorter LR than Dm-AbdA or Procambarus clarkii AbdA (Pc-AbdA) (Fig. 4A). We found that interaction with Exd in vitro was strongly HX dependent in Cs-AbdA but did not require the UbdA domain (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6). Extending the LR with Pc, Dm, or even with a polyalanine stretch imposes a similar requirement for the UbdA motif, with a variable dependency on the HX motif, which is largely dispensable with Pc-LR but is significantly required with Dm-LR or the polyalanine LR (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6). Transgenic lines allowing the expression of Cs-AbdA, Cs-AbdA(DmLR), Cs-AbdA(PcLR), and their HX-mutated variants in the Drosophila embryo indicated that although mutation of the HX resulted in a strong decrease (53%) in Cs-AbdA repressive activity on Dll expression, it had a moderate effect (39%) in Cs-AbdA(PcLR), and only a weak effect (15%) in Cs-AbdA(DmLR) (Fig. 4C). These findings indicate that extending the LR weakens the requirement of the HX for Exd-dependent Dll repression. It is noteworthy that the effect of the HX mutation in Cs-AbdA(PcLR) and Cs-AbdA(DmLR) proteins on AbdA/Exd complex assembly in vitro does not correlate with the efficiency of Dll repression in vivo (compare Fig. 4 B and C). These observations indicate that the LR region affects not only DNA binding properties but also activity regulation, as previously suggested (24). However, the UbdA dependency for Dll repression by Cs-AbdA, Cs-AbdA(PcLR), and Cs-AbdA(DmLR) could not be demonstrated, because UbdA-mutated transgenes expressed transcripts but no detectable proteins (Fig. S7).

Fig. 4.

Conserved role of the evolutionary LR extension in AbdA. (A) Alignment of AbdA peptides (HX to UbdA sequences) from Cupiennius salei (Cs) Procambarus clarkii (Pc), Drosophila melanogaster (Dm), and the modified Cs-AbdA(DmLR), Cs-AbdA(PcLR), and Cs-AbdA(LRala) proteins. (B) EMSA of Cs-AbdA variants on the DllR probe. Lanes 1 and 2: DllR probe alone and in the presence of fixed amount of Exd and Hth; lanes 3–26: fixed amount of Exd and Hth and fixed, identical amount of Cs-AbdA variants. Bars above the gel indicate the amount of protein present in the experiment. (C) (Upper) Repressive potentials in Drosophila of Cs-AbdA variants. arm-Gal4–driven ubiquitous expression of the variants (red) represses the Dll reporter gene (green) to different extents. (Lower) Quantifications of Dll reporter repression. The error bars represent SDs, and numbers above the brackets indicate P values.

In summary, the LR in Ubx and AbdA influences the Exd interaction mode. Because the sequence identity of the LR of Dm-Ubx and Dm-AbdA, and of Dm-AbdA and Pc-AbdA are strongly divergent, we concluded that divergent sequences can promote the UbdA-mediated Exd interaction mode. The distinct efficiencies in promoting the UbdA interaction mode by an LR with a distinct sequence identity but a similar number of amino acids suggests the existence of protein sequence constraints within the LR.

UbdA Motif Is Dispensable for Exd-Dependent Dm-UbxIa–Mediated Specification of Segment Identity.

To address whether the presence of an extended LR generally imposes a UbdA-dependent Exd interaction mode, we explored motif requirements for Dm-UbxIa–mediated segment-identity specification. Previous work showed that although Dm-UbxIa promotes A1 identity, Dm-UbxIa mutated for the HX promotes A2 identity instead, mimicking the activity of Dm-UbxIa in the absence of zygotic Exd activity (11, 22). These results suggest that Exd interaction in the process of segment-identity specification by Dm-UbxIa occurs through the HX motif, a conclusion confirmed by the observation that in the complete absence of exd (maternal and zygotic loss), or in hth mutants that phenocopy complete loss of exd, Dm-UbxIa still promotes A2 identity (Fig. S8). To assess whether the UbdA motif also contributes to Exd interaction in this context, we investigated the activity of the Dm-UbxIa mutant for UbdA and found that it promotes T1-like identity, as evidenced by the appearance of the beard, a T1-specific feature under Sex comb reduced (Scr) control (Fig. 5A). These observations suggest that Dm-UbxIaUbdA has acquired Scr-like activity, as confirmed further by the absence of ectopic Scr transcripts following Dm-UbxIaUbdA expression (Fig. 5B). Thus, Dm-UbxIaUbdA behaves distinctly from Dm-UbxIa in the absence of Exd. Together with the activity of Dm-UbxIaHX, this difference suggests that, in the process of segment-identity specification, despite the presence of an extended LR, the HX, instead of the UbdA motif, promotes Exd interaction.

Fig. 5.

Motifs’ requirements for segment-identity specification by Dm-UbxIa. (A) Anterior regions of wild-type and of ubiquitously expressing Dm-UbxIa, Dm-UbxIaHX, or Dm-UbxIaUbdA first-instar larvae. Arrows point toward “beards,” small denticles in the naked region of T1 and T1-like transformed segments (T1′). (B) Distribution of Scr transcripts (green) in wild-type and ubiquitously expressing Dm-UbxIa or Dm-UbxIaUbdA embryos (red). No ectopic Scr transcripts are detected in T2 and T3 segments.

Discussion

Insights into the Selection of Hox–Exd Interaction Modes.

The finding that the UbdA motif promotes interaction with Exd showed that Hox–Exd interaction does not occur solely through the HX motif, introducing diversity in Hox–Exd interaction modes. In principle, interaction with Exd may occur through the exclusive use of one or the other of these protein motifs or through a balanced combination of both. In any case, the use of generic (HX) and/or paralog-specific (UbdA) interaction modes needs to be controlled.

We found that LR extension in Ubx, and most likely in AbdA, promotes the transition from an HX-dependent to a UbdA-dependent interaction mode in the process of Dll repression. In addition we found that, despite an extended LR, Dm-UbxIa uses an HX-mediated Exd interaction in the process of segment-identity specification. These findings indicate that the LR does not promote the UbdA-dependent Exd interaction mode in all situations, suggesting that the identity of the cis regulatory target sequence also affects the choice of interaction mode. It also emphasizes that the function of the UbdA motif, as already shown for the HX motif (25, 32), is not dedicated exclusively to Exd interaction.

Interestingly, LR size is a paralog-specific feature (3, 33), with anterior Hox proteins displaying extended LR compared with posterior Hox proteins. Thus, although the UbdA motif is specific to some central Hox paralogs, the LR generally may fine-tune Hox–PBC interactions by controlling the balance between generic HX-dependent and paralog-specific interaction modes that are yet to be identified in other paralog groups.

Functional Impacts Resulting from Changes in the Hox–Exd Interaction Mode.

The existence of at least two Exd interaction modes for the central Hox paralog proteins Ubx and AbdA raises the question whether these qualitatively distinct Hox/Exd complexes have distinct activities. Our data provide support for such distinct activities. Modifying the interaction mode does affect the efficiency of Dll repression: Dm-UbxIa, Cs-Ubx(DmLR), and Cs-AbdA(DmLR) repress Dll with a stronger efficiency than DmUbx-IVa, Cs-Ubx, and Cs-AbdA. These results indicate that repression of Dll is more efficient when the complex is assembled through a UbdA interaction mode.

However, in contrast to the effects seen on Dll expression, we did not found significant differences in binding affinities of Hox/Exd complexes assembled through distinct interaction modes: Changing the balance from an HX- to a UbdA-dependent mode by modifying the LR in Cupiennius Ubx and AbdA proteins does not affect binding affinity significantly (Figs. S5 and S6); Dm-UbxIa and Dm-UbxIVa form Ubx/Exd complexes with similar affinities (21). These observations indicate that, in the case of Dll regulation, modifying the mode of interaction does not affect DNA binding. However, the distinct DNA binding affinities displayed by Dm-UbxIa and Dm-UbxIVa on a composite Hox/Exd site (34) suggest that modifying the mode of interaction may have a different effect on other targets.

We propose that HX- and UbdA-assembled Hox/Exd complexes have the potential for distinct activities, affecting either DNA binding or a later step of transcriptional regulation (efficiency of activation or repression). This potential may result from changes in the overall or local conformation in the Hox/Exd complex that intrinsically affect binding properties and/or modify interfaces toward additional protein partners involved in target gene regulation. Such a scenario also explains the importance of LR sequence identity (Pc or Dm) in regulating the activity of AbdA/Exd complexes.

Subtle Changes in Hox Protein Function Through a Co-Option Mechanism.

Hox proteins have served as paradigms for studying how evolutionary changes in protein sequences affect morphological diversity. The few available reports were associated with drastic changes in Hox protein function (22, 35–38). Our work, instead, highlights protein changes that have distinct features.

First, changes in protein activity are subtle rather than drastic and, in the case studied, do not drive morphological changes: Although the acquisition of the LR changes the Ubx–Exd interaction mode, the absence of legs in chelicerates and insects argues that each of the two interaction modes is sufficiently efficient to repress Dll. Such subtle changes in protein activity (defined as Dll repressive activity), initially not affecting protein function (defined as the morphological outcome, i.e., suppression of legs), may contribute to morphological changes when associated with complementary changes in cis regulatory sequences or changes in levels of protein expression in the context of evolution.

Second, although previous work demonstrated that protein changes rely directly on the functional attribute of the motif that was gained or lost, the acquisition of the LR in insect Ubx/AbdA proteins acts through preexisting motifs, the HX motif (present in all bilaterian Ubx/AbdA proteins) and the UbdA motif (present in all protostome Ubx/AbdA proteins). Co-opting the UbdA motif for Exd interaction through LR extension may have released functional constraint on the HX motif, thereby allowing the HX to acquire novel functions. Such novel functions of the HX have been demonstrated previously for AbdA (25) and also for Antp (32), suggesting that similar mechanisms may operate in more distant non-UbdA–containing Hox proteins. We propose that the mechanism of protein motif co-option identified here has the potential to promote functional shuffling of protein domains. This mode of protein evolution, subtle and regulated rather than drastic, provides more room for the idea that protein sequence, in addition to cis-regulatory sequences, is the template for molecular and morphological evolution.

Experimental Procedures

Flies, Egg Collections, Immunostaining, in Situ Hybridization, and Cuticle Preparation.

Alleles used were exdXP11 and hth P2. Exd maternal deprivation was achieved by generating exd germ-line clones. All transgenes were HA tagged. Embryo collection, immunodetection, and cuticle preparations were performed according to standard procedures. Antibodies against HA tag (rat; 1:500; Invitrogen), to Ubx (FP3.38; 1:1000), AbdA (rabbit polyclonal; 1:1,000), and β-galactosidase (1:500) were used. Digoxigenin RNA-labeled probes were generated from Scr or Cs-AbdA full-length cDNAs according to the manufacturer's protocol (Boehringer-Mannheim).

Constructs, Transgenic Lines, and in Vivo Reporter Analysis.

Ubx cDNAs were provided by W. McGinnis (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA) for Artemia and by M. Akam (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom) for Strigamia. Cs-Ubx is Ubx2. Accession numbers for sequences used in this study are Af-Ubx, Q8WRG5; Stm-Ubx, Q1KY84; Dm-UbxIVa, AAF55355; Dm-UbxIVb, AAS65158; Dm-UbxIIb, AAN13719; Dm-UbxIa, AAN13178; and Cs-AbdA, AJ007436. The Pc-AbdA sequence is from ref. 39. Hox variant constructs were generated by PCR from full-length cDNAs. HX and UbdA mutations for Cs-, Af-, and Stm-Ubx and for Cs-AbdA are YPWM to YAAA and KELNEQ to KAAAAQ. Primers used are available upon request. All constructs were cloned in the pcDNA3 vector and were sequence verified. Mutations of Dm-Ubx are as previously described (18). Constructs for fly transformation were cloned in the pUAST vector, and transgenic lines were established by P-element–mediated germ-line transformation. Collected embryos were stained with anti-HA to select the conditions (line and temperature) that result in expression levels similar to endogenous Ubx or AbdA levels in A1 and A2, respectively (Fig. S2) (18, 22). Quantification of Dll repression, assessed by measuring the loss of DME-lacZ reporter activity following Ubx expression, was achieved using the DME-lacZ insertion previously described (18). Error bars represent the deviation from the average value (18 < n < 27). P values were calculated using the nonparametric Wilcoxon test.

Protein Expression and Electromobility Gel Shift Assays.

Exd, Hth, Ubx, and AbdA proteins were full length. Proteins were produced with the TNT (T7) coupled in vitro transcription/translation system (Promega). Production yields of Hox proteins and variants were analyzed after scanning gel containing [35S]methionine-labeled protein and identical amounts of wild-type or mutated proteins were used in band shift assays, performed as previously described (25) using 4 μL of a doubly programmed Exd/Hth lysate. The probe used was DIIR (24). Relative DNA binding affinity for Ubx or AbdA variants was measured with ImageJ software. When several Hox concentrations were used, quantifications were performed on the intermediate Hox concentration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. McGinnis and R. Mann for providing UAS-Af-Ubx and DME-lacZ lines, M. Akam for the Stm-Ubx cDNA, R. White for antibodies, and E. Sanchez-Herrero and C. Alonso for Ubx isoforms, B. Hudry for discussions, and B. Hudry, A. Saurin, J. Deutsch, and M. Akam for comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Université de la Méditerranée, and by grants from the Centre Franco-Indien pour la Promotion de Recherche Avancée, the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche, Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, and Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer to Y.G., and a fellowship from Ministère de la Recherche et Technologie and Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer to M.S.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1006964108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pearson JC, Lemons D, McGinnis W. Modulating Hox gene functions during animal body patterning. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:893–904. doi: 10.1038/nrg1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann RS, Lelli KM, Joshi R. Hox specificity unique roles for cofactors and collaborators. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;88:63–101. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)88003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merabet S, Hudry B, Saadaoui M, Graba Y. Classification of sequence signatures: A guide to Hox protein function. Bioessays. 2009;31:500–511. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann RS, Chan S-K. Extra specificity from extradenticle: The partnership between HOX and PBX/EXD homeodomain proteins. Trends Genet. 1996;12:258–262. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan SK, Ryoo HD, Gould A, Krumlauf R, Mann RS. Switching the in vivo specificity of a minimal Hox-responsive element. Development. 1997;124:2007–2014. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.10.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann RS, Affolter M. Hox proteins meet more partners. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:423–429. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moens CB, Selleri L. Hox cofactors in vertebrate development. Dev Biol. 2006;291:193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson FB, Parker E, Krasnow MA. Extradenticle protein is a selective cofactor for the Drosophila homeotics: Role of the homeodomain and YPWM amino acid motif in the interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:739–743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knoepfler PS, Kamps MP. The pentapeptide motif of Hox proteins is required for cooperative DNA binding with Pbx1, physically contacts Pbx1, and enhances DNA binding by Pbx1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5811–5819. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remacle S, et al. Loss of function but no gain of function caused by amino acid substitutions in the hexapeptide of Hoxa1 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8567–8575. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8567-8575.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galant R, Walsh CM, Carroll SB. Hox repression of a target gene: Extradenticle-independent, additive action through multiple monomer binding sites. Development. 2002;129:3115–3126. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan S-K, Pöpperl H, Krumlauf R, Mann RS. An extradenticle-induced conformational change in a HOX protein overcomes an inhibitory function of the conserved hexapeptide motif. EMBO J. 1996;15:2476–2487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passner JM, Ryoo HD, Shen L, Mann RS, Aggarwal AK. Structure of a DNA-bound Ultrabithorax-Extradenticle homeodomain complex. Nature. 1999;397:714–719. doi: 10.1038/17833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi R, et al. Functional specificity of a Hox protein mediated by the recognition of minor groove structure. Cell. 2007;131:530–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piper DE, Batchelor AH, Chang CP, Cleary ML, Wolberger C. Structure of a HoxB1-Pbx1 heterodimer bound to DNA: Role of the hexapeptide and a fourth homeodomain helix in complex formation. Cell. 1999;96:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaRonde-LeBlanc NA, Wolberger C. Structure of HoxA9 and Pbx1 bound to DNA: Hox hexapeptide and DNA recognition anterior to posterior. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2060–2072. doi: 10.1101/gad.1103303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medina-Martínez O, Ramírez-Solis R. In vivo mutagenesis of the Hoxb8 hexapeptide domain leads to dominant homeotic transformations that mimic the loss-of-function mutations in genes of the Hoxb cluster. Dev Biol. 2003;264:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merabet S, et al. A unique Extradenticle recruitment mode in the Drosophila Hox protein Ultrabithorax. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16946–16951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705832104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balavoine G, de Rosa R, Adoutte A. Hox clusters and bilaterian phylogeny. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2002;24:366–373. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(02)00237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan S-K, Mann RS. The segment identity functions of Ultrabithorax are contained within its homeo domain and carboxy-terminal sequences. Genes Dev. 1993;7:796–811. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gebelein B, McKay DJ, Mann RS. Direct integration of Hox and segmentation gene inputs during Drosophila development. Nature. 2004;431:653–659. doi: 10.1038/nature02946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ronshaugen M, McGinnis N, McGinnis W. Hox protein mutation and macroevolution of the insect body plan. Nature. 2002;415:914–917. doi: 10.1038/nature716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brena C, Chipman AD, Minelli A, Akam M. Expression of trunk Hox genes in the centipede Strigamia maritima: Sense and anti-sense transcripts. Evol Dev. 2006;8:252–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebelein B, Culi J, Ryoo HD, Zhang W, Mann RS. Specificity of Distalless repression and limb primordia development by abdominal Hox proteins. Dev Cell. 2002;3:487–498. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merabet S, et al. The hexapeptide and linker regions of the AbdA Hox protein regulate its activating and repressive functions. Dev Cell. 2003;4:761–768. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.González-Reyes A, Morata G. The developmental effect of overexpressing a Ubx product in Drosophila embryos is dependent on its interactions with other homeotic products. Cell. 1990;61:515–522. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90533-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann RS, Hogness DS. Functional dissection of Ultrabithorax proteins in D. melanogaster. Cell. 1990;60:597–610. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90663-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angelini DR, Kaufman TC. Comparative developmental genetics and the evolution of arthropod body plans. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:95–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.112310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kornfeld K, et al. Structure and expression of a family of Ultrabithorax mRNAs generated by alternative splicing and polyadenylation in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1989;3:243–258. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bomze HM, López AJ. Evolutionary conservation of the structure and expression of alternatively spliced Ultrabithorax isoforms from Drosophila. Genetics. 1994;136:965–977. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.López AJ, Artero RD, Pérez-Alonso M. Stage, tissue, and cell specific distribution of alternative Ultrabithorax mRNAs and protein isoforms in the Drosophila embryo. Rouxs Arch Dev Biol. 1996;205:450–459. doi: 10.1007/BF00377226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prince F, et al. The YPWM motif links Antennapedia to the basal transcriptional machinery. Development. 2008;135:1669–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.018028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.In der Rieden PM, Mainguy G, Woltering JM, Durston AJ. Homeodomain to hexapeptide or PBC-interaction-domain distance: Size apparently matters. Trends Genet. 2004;20:76–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed HC, et al. Alternative splicing modulates Ubx protein function in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2010;184:745–758. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.112086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Löhr U, Yussa M, Pick L. Drosophila fushi tarazu. a gene on the border of homeotic function. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1403–1412. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00443-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Löhr U, Pick L. Cofactor-interaction motifs and the cooption of a homeotic Hox protein into the segmentation pathway of Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol. 2005;15:643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galant R, Carroll SB. Evolution of a transcriptional repression domain in an insect Hox protein. Nature. 2002;415:910–913. doi: 10.1038/nature717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch VJ, et al. Adaptive changes in the transcription factor HoxA-11 are essential for the evolution of pregnancy in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14928–14933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802355105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abzhanov A, Kaufman TC. Embryonic expression patterns of the Hox genes of the crayfish Procambarus clarkii (Crustacea, Decapoda) Evol Dev. 2000;2:271–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2000.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.