SUMMARY

It remains a challenge to create the stable and long-term expression (in human cell lines) of a previously engineered hybrid enzyme (Trip-cat enzyme-2, [Ruan, KH., et al. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 14003 – 14011]), which links cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) to prostacyclin (PGI2) synthase (PGIS) for the direct conversion of arachidonic acid into PGI2 through the enzyme’s triple-catalytic (Trip-cat) functions. The stable up-regulation of the biosynthesis of the vascular protector, PGI2, in cells is an ideal model for the prevention and treatment of thromboxane A2 (TXA2)-mediated thrombosis and vasoconstriction, both of which cause stroke, myocardial infarction, and hypertension. Here, we report another engineering of the Trip-cat enzyme, in which human COX isoform-1 (COX-1), which has a different C-terminal sequence than COX-2, was linked to PGIS and called the Trip-cat Enzyme-1. Transient expression of the recombinant Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in HEK293 cells demonstrated a 3–5-fold higher expression capacity and better PGI2-synthesizing activity when compared to that of the previously engineered Trip-cat Enzyme-2. Furthermore, an HEK293 cell line that can stably express the active new Trip-cat Enzyme-1 and constantly synthesize the bioactive PGI2 was established by a screening approach. In addition, the stable HEK293 cell line, with a constant production of PGI2, revealed strong anti-platelet aggregation properties through its unique dual functions (increasing PGI2 production while decreasing TXA2 production) in the TXA2 synthase (TXAS)-rich plasma. This study has optimized the active Trip-cat enzyme engineering, allowing it to become the first to stably up-regulate PGI2 biosynthesis in a human cell line, which provides a basis for developing a PGI2-producing therapeutic cell line against vascular diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Prostacyclin (PGI2)1, which has strong anti-platelet aggregation and vasodilation properties [1–4], and is synthesized from endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, has been identified as one of the most important vascular protectors against thrombosis and heart disease [5]. Recently, there have been many new studies which have confirmed the importance of PGI2 in vascular protection. For instance, it was discovered that PGI2 receptor (IP)-knocked out mice showed an increase in thrombosis tendency [6]. Also, the suppression of PGI2 biosynthesis by cyclooxygenase (COX) isoform-2 (COX-2) inhibitors was linked to increased heart disease in human clinical trials [7]. Thus, increasing the biosynthesis of PGI2 would be very useful for the protection of the vascular system. It is known that the biosynthesis of prostanoids through the arachidonate-COX pathway occurs when arachidonic acid (AA) is first converted into prostaglandin G2 (PGG2, catalytic step 1), and then to prostaglandin endoperoxide (prostaglandin H2 (PGH2)) (catalytic step 2) by COX isoform-1 (COX-1) or COX-2 in cells [8]. The PGH2 then serves as a common substrate for downstream synthases and is isomerized to prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), E2 (PGE2), F2 (PGF2), and I2 (PGI2) or thromboxane A2 (TXA2) by individual synthases (catalytic step 3). The over-production of TXA2, a proaggregatory and vasoconstricting mediator has been identified as one of the key factors that cause thrombosis, stroke, and heart disease [1, 2]. PGI2 is the primary AA metabolite in vascular walls and has opposite biological properties to that of TXA2 and therefore represents the most potent endogenous vascular protector — acting as an inhibitor of platelet aggregation and a strong vasodilator on vascular beds [9–12]. Specifically increasing PGI2 biosynthesis requires a highly efficient chain reaction between COX and PGIS, which consists of the triple catalytic (Trip-cat) functions mentioned above.

Recently, we engineered a hybrid enzymatic protein with the ability to perform the Trip-cat functions by linking the inducible COX-2 to PGIS through a transmembrane domain [13, 14]. Here, we refer to this previously engineered enzyme as the Trip-cat Enzyme-2. The transient expressions of the active Trip-cat Enzyme-2 in HEK293 and COS-7 cells have been demonstrated. However, there are concerns in using the Trip-cat Enzyme-2 in vivo because COX-2 has an inducible nature, a less likely capacity to express stably, and may also lead to numerous pathological processes, such as cancers and inflammation. Given the nature of the COX-1, a house-keeping enzyme that is consistently expressed in cells, we hypothesize that a Trip-cat enzyme, constructed by linking COX-1 to PGIS, is likely to demonstrate a stable expression in the cells and therefore a constant production of the vascular protective prostanoid, PGI2. To test this hypothesis, in this paper we demonstrate the construction of a new Trip-cat enzyme linking COX-1 to PGIS which we call the Trip-cat Enzyme-1. Our studies have confirmed that the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 could be stably expressed in HEK293 cells and therefore lead to the generation of a cell line that constantly delivers the vascular protector, PGI2. This study has provided a fundamental step toward specifically and stably upregulating PGI2 biosynthesis in therapeutic cells for the prevention and treatment of thrombosis and heart disease.

RESULTS

Design of a New Generation Trip-cat Enzyme (COX-1 Linked to PGIS) That Directly Converts AA into the Vascular Protector, PGI2

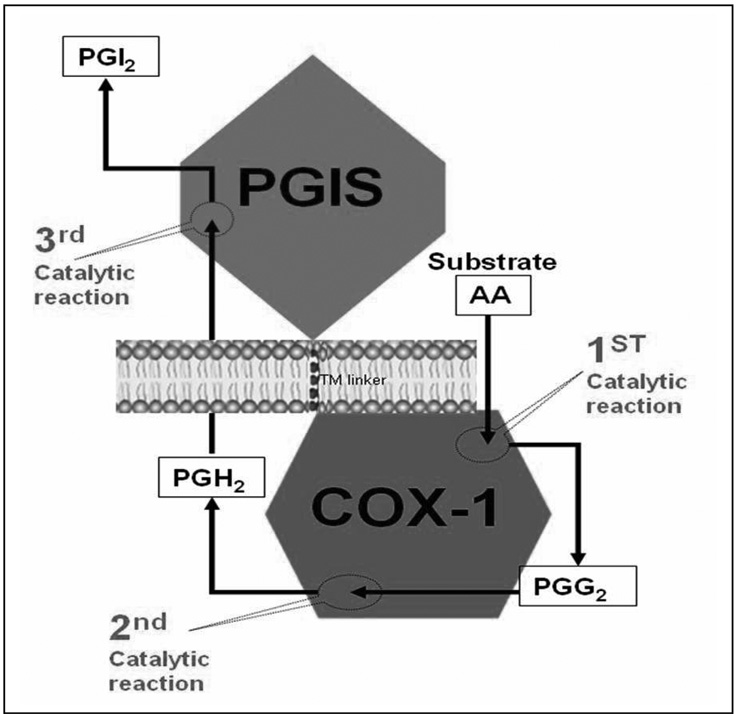

As described in the introduction, we recently invented an approach for engineering an active hybrid enzyme (Trip-cat Enzyme-2) by linking the human COX-2 to PGIS (COX-2-linker-PGIS) which demonstrated triple-catalytic activities in converting AA to PGG2, PGH2, and finally into PGI2 [13, 15, Figure 1]. This finding generated a great potential for specifically up-regulating PGI2 biosynthesis in ischemic tissues through the introduction of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 gene into these target tissues. On the other hand, there is the COX-1 enzyme, which is well-known to have a similar function (coupling to PGIS to synthesize PGI2 in vitro and in vivo) to that of COX-2. The house-keeping enzyme, COX-1, which has less pathological impacts, could be safer for gene and cell therapies when compared to that of COX-2, which is involved in the pathological processes of inflammation and cancers, and has inducible transient-expression nature. This suggested that the Trip-cat Enzyme containing COX-1 (Figure 1) may have better therapeutic potential than that containing COX-2 in terms of the stable expression in cells and pathogenic property. Also, the X-ray crystal structure shows that the membrane orientation and the membrane anchor domain of COX-1 are similar to those of COX-2. This has led us to design a single molecule containing the cDNA of human COX-1 and PGIS with a connecting TM linker derived from human bovine rhodopsin [15] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A model of the newly designed Trip-cat Enzyme-1. The Trip-cat Enzyme-1 was created by linking COX-1 to PGIS through an optimized TM linker (10 amino acid residues) without alteration of the protein topologies in the ER membrane. The three catalytic sites and reaction products in COX-1 and PGIS enzymes are shown.

Cloning of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 by Linking COX-1 to PGIS

A PCR approach was used to link the C-terminus of human COX-1 (NCBI GenBank ID: NM_080591) to human PGIS (NCBI GenBank ID: D38145) by a helical linker with 10 residues (His-Ala-Ile-Met-Gly-Val-Ala-Phe-Thr-Trp) derived from human rhodopsin. The resultant cDNA sequence encoding the novel Trip-cat Enzyme-1 (COX-1-10aa-PGIS) was then subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector for mammalian cell expression [13]. It shall be noted that the entire cDNA sequence of Trip-cat Enzyme-1 encodes a single human protein sequence, which could be used for therapeutics.

Expression of the Engineered Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in HEK293 Cells

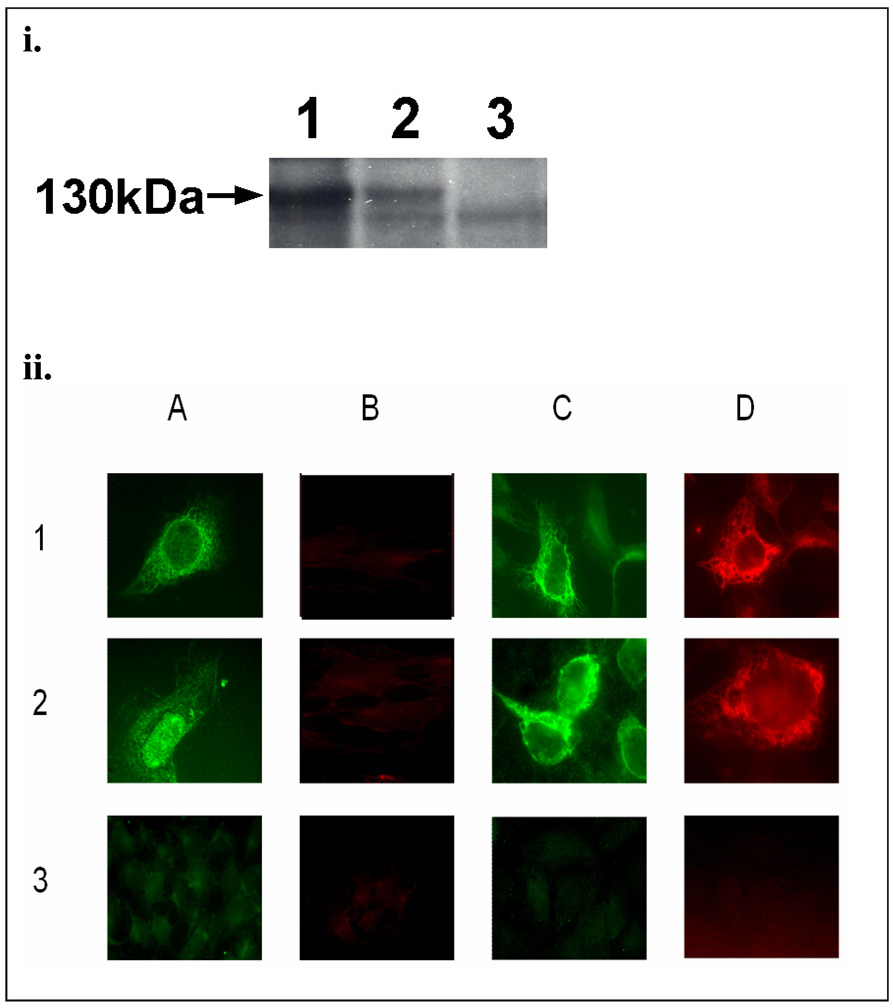

Despite the many similarities between human COX-1 and COX-2, there are several important differences that still exist. For example, it has been reported that the C-terminal Leu and the last six residues of COX-1 are important in the enzyme’s activity [16]. However, they are not identical to those of COX-2. Therefore, it becomes interesting to investigate whether the linkage (from the C-terminal Leu of COX-1 to the N-terminus of PGIS) in the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 would affect its expression, protein folding, and enzyme activity. Using the constructed pcDNA3.1 COX-1-10aa-PGIS plasmid, the recombinant COX-1-10aa-PGIS protein was successfully overexpressed in the HEK293 cell line by showing the correct molecular mass of approximately 130 kDa in the Western blot analysis (Figure 2i, lane 1). This indicated that the linkage from the C-terminal Leu of COX-1 to the N-terminus of PGIS has no effect on the Trip-cat Enzyme expression. In addition, a comparison of the expression levels between COX-1-10aa-PGIS and COX-2-10aa-PGIS revealed that the transfected HEK293 cells expressed approximately 3-folds more COX-1-10aa-PGIS protein than that of the COX-2-10aa-PGIS protein under identical conditions (Figure 2i, lane 2).

Figure 2.

(i).Western blot analysis for the over-expressed COX-1-10aa-PGIS and COX-2-10aa-PGIS in HEK293 cells. The HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the cDNA of COX-1-10aa-PGIS (lane 1), COX-2-10aa-PGIS (lane 2) or the pcDNA 3.1 vector alone (lane 3) were solubilized and separated by 7% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The expressed Trip-cat Enzymes were stained by anti-PGIS antibody. The molecular weight (130 kDa) of the engineered enzymes is indicated with an arrow. (ii). Immunofluorescence micrographs of HEK293 cells. In brief, the cells were grown on cover-slides and transfected with the cDNA plasmid(s) of the COX-1-10aa-PGIS (row 1), co-transfected COX-1 and PGIS (row 2) or the pcDNA 3.1 vector alone (row 3). The cells were permeabilized by SLO (panels A and B) or saponin (panels C and D) and then incubated with the affinity-purified rabbit anti-PGIS peptide antibody (A and C) or mouse anti-COX-1 antibody (B and D) [13]. The bound antibodies were stained by FITC-labeled goat-anti rabbit IgG (A and C) or rhodamine-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (B and D). The stained cells were then examined by fluorescence microscopy [13].

Subcellular Localization of the COX-1-10aa-PGIS

To determine whether the linkage of the C-terminal Leu of COX-1 to PGIS caused any effects on the subcellular localization of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1, the HEK293 cells expressing the enzyme, COX-1-10aa-PGIS, were permeabilized and stained. Non-significant differences were observed in the ER staining patterns for the cells treated with streptolysin-O (SLO), which selectively permeabilized the cell membrane, or with saponin, which generally permeabilized both the cell and the ER membranes (Figure 2ii). The results indicated that the modification of the linkage between the COX-1 Leu residue and the PGIS N-terminus had no significant effect on the subcellular localization of the COX-1-10aa-PGIS in the cells. The idea that the PGIS domain is located on the cytoplasmic side of the ER and that the COX-1 domain is located on the ER lumen for the overexpressed COX-1-10aa-PGIS was also supported by the immunostaining. The anti-PGIS antibody was used to stain the cells treated by SLO or saponin, but anti-COX-1 antibody would only stain the cells treated with saponin (Figure 2ii). This data further confirmed that the 10aa linkage from COX-1 to PGIS had no significant effects on the subcellular localization of the COX-1 and PGIS in the ER membrane.

Triple catalytic activities of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in Directly Converting Arachidonic Acid into the Vascular Protector, Prostacyclin

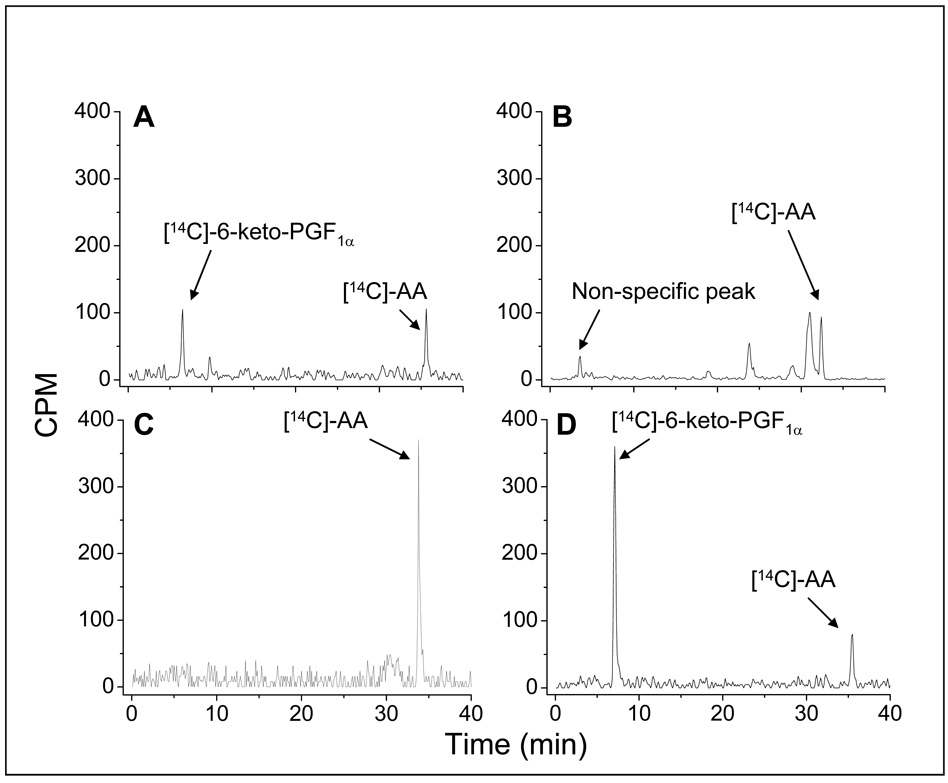

The biological activities of HEK293 cells expressing the different eicosanoid-synthesizing enzymes that convert AA to PGI2 were assayed by the addition of [14C]-AA. The resultant [14C]-eicosanoids, metabolized by the enzymes in the cells, were profiled by the HPLC-analysis (HPLC separation linked to an automatic scintillation analyzer, Figure 3). The triple catalytic activities that occur during the conversion of [14C]-AA to [14C]-6-keto-PGF1α (degraded PGI2) require two individual enzymes, COX-1 and PGIS, in the HEK293 cells (Figure 3A) because neither COX-1 (Figure 3B) nor PGIS (Figure 3C) alone could produce [14C]-6-keto-PGF1α from the [14C]-AA in the HEK293 cells. However, the cells expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 were able to integrate the triple catalytic activities of the COX-1 and PGIS by converting the added [14C]-AA to the end product, [14C]-6-keto-PGF1α (Figure 3D). It should be noted that in HEK293 cells expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1, most of the added [14C]-AA was converted to [14C]-6-keto-PGF1α with very minimal byproducts. In contrast, the cells co-expressing COX-1 and PGIS synthesized less PGI2 and produced a significant amount of other unidentified lipid molecules. These data clearly indicated that the enzymatic conversion of AA to PGI2 is more efficient in the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 than that of the co-expressed individual COX-1 and PGIS.

Figure 3.

Determination of the triple-catalytic activities of the fusion enzymes for directly converting AA to PGI2, using an isotope-HPLC method for HEK293 cells. Briefly, the cells (~0.1 × 106) transfected with the cDNA(s) of both COX-1 and PGIS (A), COX-1 (B), PGIS (C), and COX-1-10aa-PGIS (D) were washed and then incubated with [14C]-AA (10 µM) for five min. The metabolized [14C]-eicosanoids from the [14C]-AA in the supernatant were analyzed by HPLC on a C18 column (4.5 × 250 mm) connected to a liquid scintillation analyzer. The total counts for the specific peaks in each assay are approximately: 400 counts in A; 550 counts in B; 600 counts in C, and 750 counts in D.

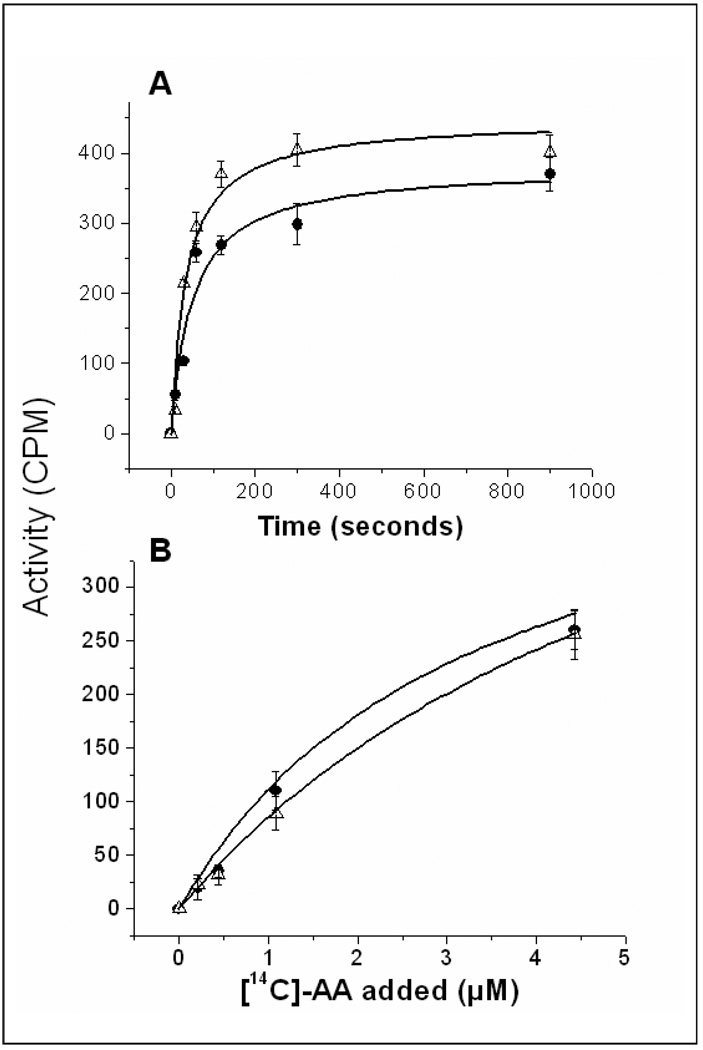

Enzyme Kinetics of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 Compared to That of Its Parent Enzymes

In the cells co-expressing COX-1 and PGIS, the coordination of COX-1 and PGIS in the ER membrane (for the biosynthesis of PGI2 from AA) is very fast. Only 120 seconds were required to reach 50% of the maximum activity (Figure 4A, triangles). The reaction was almost saturated after approximately 5 minutes. The amount of PGI2 produced when the reaction was extended from 5 minutes to 15 minutes only increased by 5%. On the other hand, the cells expressing the engineered Trip-cat Enzyme-1 (Figure 4A, closed circles) could adopt the same time-course pattern as that of the co-expressed wild-type COX-1 and PGIS. In addition, the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 also adopted an identical dose-dependent response of the parent enzymes in biosynthesis of PGI2 (Figure 4B). The Km and Vmax values for the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 are approximately 5 µM and 400 µM, respectively, which are almost identical to that of the co-expressed COX-1 and PGIS. This study has indicated that the expressed Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in the cells has the correct protein folding, subcellular localization, and native enzymatic functions in a single folded protein, similar to that of its parent enzymes.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the time course (A) and dose-dependent response (B) of the HEK293 cells expressing Trip-cat Enzyme-1 (closed circles) and co-expressing its parent enzymes, COX-1 and PGIS (triangles). The assay and HPLC analysis conditions used are described in Fig. 3.

Establishing a Stable Expression of the Trip-Cat Enzyme-1 in cells

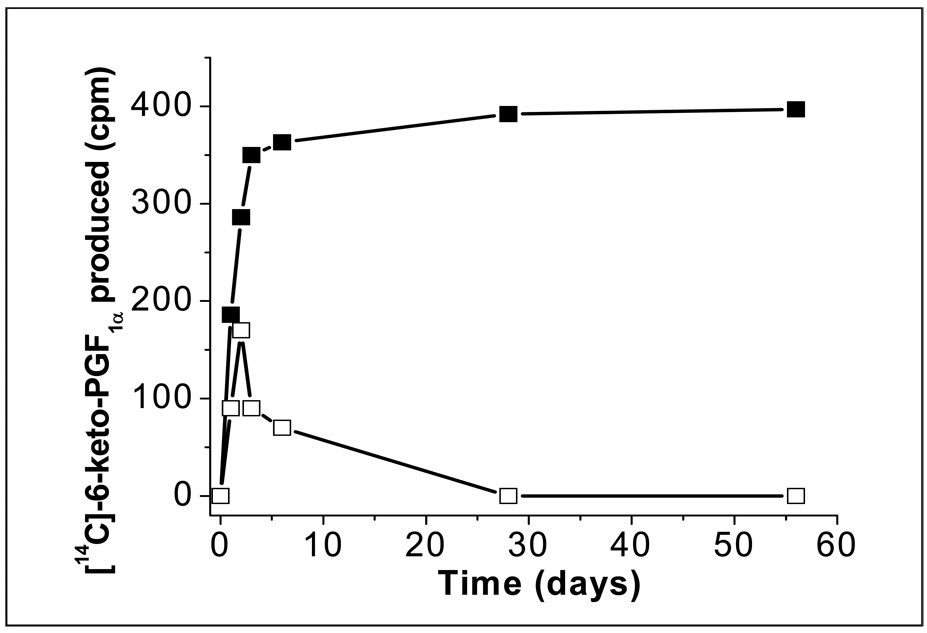

Stable expression of the engineered Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in the cells is the basis for having the cells constantly produce PGI2. In this study, an HEK293 cell line was used as the model for testing. After G418 screening for the transiently transfected HEK293 cells containing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 cDNA, the cells stably expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 were successfully created, as evidenced from the enzyme activity assays showing a continuous [14C]-PGI2 production from the addition of [14C]-AA (Figure 5, black squares). However, the same cells transfected with the COX-2-10aa-PGIS cDNA could only produce PGI2 for a few days (Figure 5, open squares), due to a failure in the stable expression of the Trip-cat Enzyme-2. This study indicated that the engineered Trip-cat Enzyme-1 most likely adopted the house-keeping properties of COX-1, which produced a constant expression in the cells, whereas the Trip-cat Enzyme-2 mainly adopted the inducible COX-2 properties which only expressed the protein for a short period of time.

Figure 5.

Time course experiment for the HEK293 cells expressing the recombinant Trip-cat Enzymes. The cells transfected with the cDNA of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 (black squares) or the Trip-cat Enzyme-2 (white squares) were selected by the G418 screening approach as described in the Experimental Procedures and then taken for assay analysis at different days following the transfection. The assay conditions for the Tri-cat enzymes are described in Figure 3 [13].

Anti-Platelet Aggregation

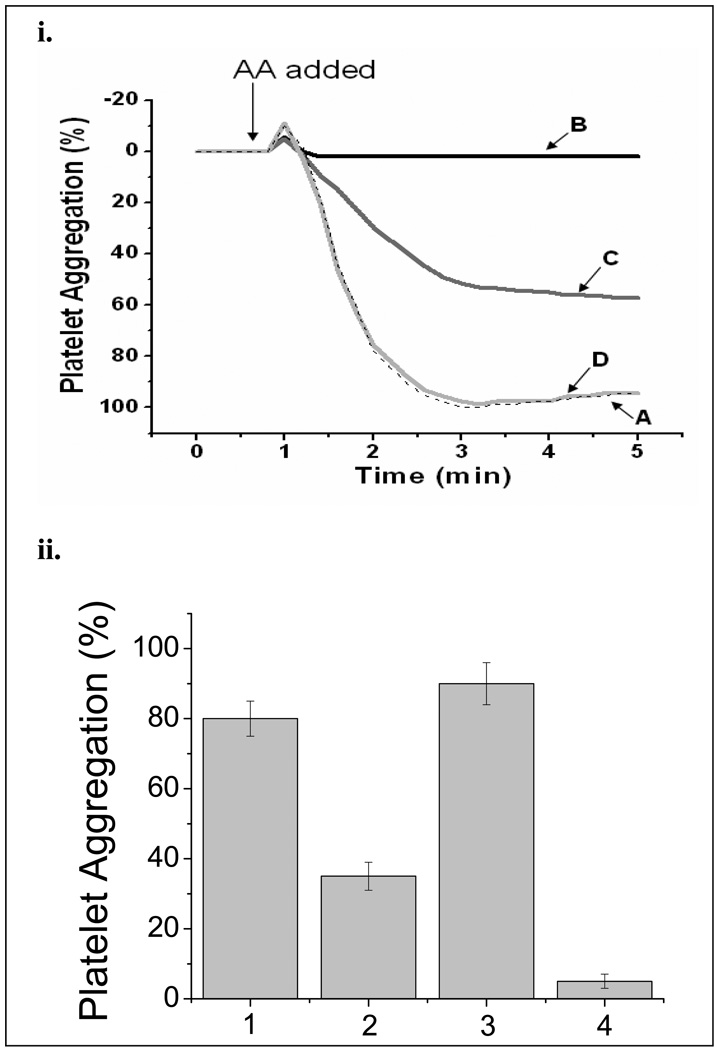

The effects of the HEK293 cells expressing COX-1-10aa-PGIS on anti-platelet aggregation were explored. It is known that platelets contain large amounts of COX-1 and TXAS. When AA was added to the platelet-rich plasma, the platelets began to aggregate in minutes (Figure 6i, Line A). However, this aggregation was completely blocked in the presence of the cells expressing COX-1-10aa-PGIS (Figure 6i, Line B). In contrast, the aggregation was only partially blocked in the presence of the cells co-expressing COX-1 and PGIS (Figure 6i, Line C). This indicated that the AA was not only converted into PGI2 (by COX-1 and PGIS) to act against the platelet aggregation, but also converted into TXA2, promoting platelet aggregation by the abundant TXAS in the platelets. In contrast, no effects were observed from the non-transfected control, HEK293 cells (Figure 6i, Line D). Based on these observations, it is clear that the engineered Trip-cat Enzyme-1 is superior in anti-platelet aggregation compared to that of the co-expressed COX-1 and PGIS.

Figure 6.

(i) Effects of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in anti-platelet aggregation. The platelet-rich plasma was incubated with 100 µM AA at 37°C in the presence of PBS (A), the HEK293 cells expressing Trip-cat Enzyme-1 (B), HEK293 cells co-expressing individual COX-1 and PGIS (C), and non-transfected HEK293 cells (D). The amount of HEK293 cells used for the experiments were approximately 0.2 × 106 per assay. The addition of AA to the platelets is indicated with an arrow. (ii). Comparison of the effects of the HEK293 cells expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 on the platelet aggregation stimulated by collagen and AA. The platelet-rich plasma, prepared from fresh human blood, was incubated with 100 µM of collagen (bars 1 and 2) or AA (bars 3 and 4) at 37 °C in the presence of PBS (lanes 1 and 3) or HEK293 cells (0.5 × 106) expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 (lanes 2 and 4). After five minutes from the initiation of the experiment, the levels of platelet aggregation were recorded and plotted, where n=3.

To test whether the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 can indirectly inhibit platelet aggregation induced by other factors, such as collagen (through non-COX pathways), it is necessary to compare the effects of the HEK293 cells (expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1) on human platelets induced by collagen (Figure 6ii, graphs 1 and 2) against those effects of the AA-induced platelets (Figure 6ii, graphs 3 and 4). It is clear that the cells expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 could not only directly inhibit the AA-induced platelet aggregation (Figure 6ii, graph 4), but also significantly inhibited the collagen-induced platelet aggregation by up to 50% (Figure 6ii graph 2).

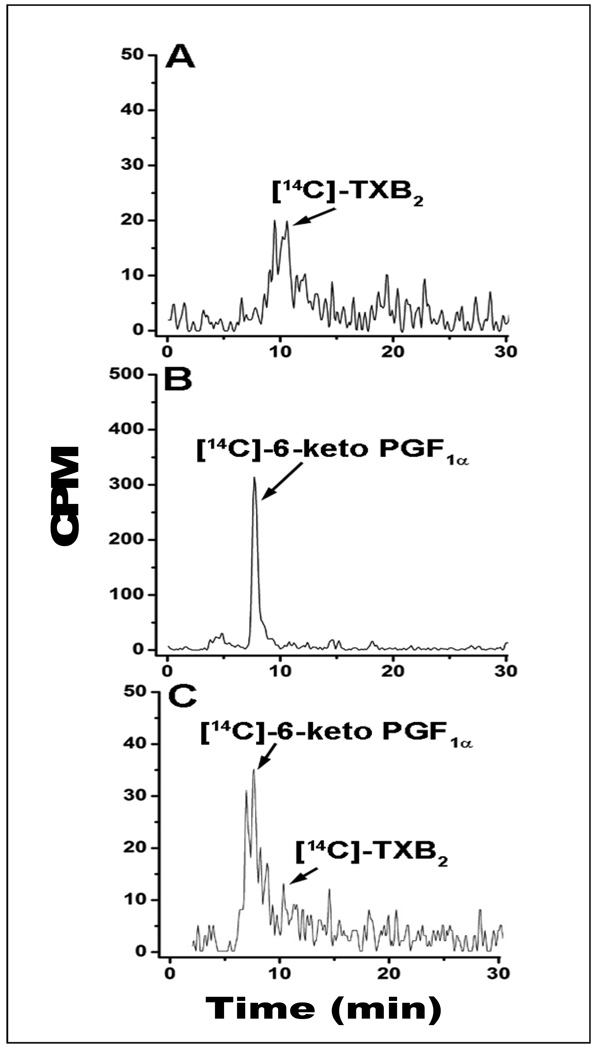

Competitively Up-regulating PGI2 Biosynthesis in the Presence of Platelets

To further demonstrate the competitive up-regulation of PGI2 biosynthesis by the COX-1-10aa-PGIS in the presence of TXAS, [14C]-AA was added to the platelet-rich plasma containing endogenous COX-1 and TXAS, in the presence and absence of the cells stably expressing COX-1-10aa-PGIS or the cells co-expressing COX-1 and PGIS. In the sample containing only platelet-rich plasma, the majority of the [14C]-AA was converted into [14C]-TXB2 (Figure 7A), indicating the presence of endogenous COX-1 and TXAS in the plasma. However, by addition of the cells expressing COX-1-10aa-PGIS into the plasma, the major product shifted to [14C]-6keto-PGF1α (degraded PGI2, Figure 7B), which demonstrated that the COX-1-10aa-PGIS could effectively compete against the endogenous COX-1 and TXAS for the substrate, [14C]-AA. On the other hand, addition of the cells co-expressing COX-1 and PGIS could only partially convert [14C]-AA to [14C]-PGI2 (Figure 7C). These results are consistent with the observations from the platelet aggregation assay described above.

Figure 7.

HPLC analysis for the profiles of the [14C]-AA metabolized by platelets in blood in the absence and presence of the HEK293 cells. [14C]-AA (10 µM) was incubated with 100 µL of fresh blood in the absence (A) and the presence of HEK293 cells (0.1 × 106) expressing COX-1-10aa-PGIS (B) or co-expressing individual COX-1 and PGIS (C) for five min. The metabolized [14C]-eicosanoids from the [14C]-AA in the supernatant were analyzed by the HPLC system as described in Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

COX-1 is a housekeeping enzyme, constantly expressed in tissues to maintain the physiological functions of the organs. However, COX-2 is an inducible enzyme and is related to the pathological processes of cancer cells and inflammation [6, 7]. From a therapeutic potential point of view, it should be safer to use the Trip-cat Enzyme constructed with COX-1 rather than that of COX-2 for up-regulating the PGI2 biosynthesis in vivo. Thus, the successful engineering of the active COX-1-10aa-PGIS represents advancement in our COX-based enzyme engineering and provides a basis for developing a novel therapeutic approach against thrombosis and ischemic diseases. It should also be noted that the COX-2-based Trip-cat Enzyme could not be simply replaced by the COX-1-based Trip-cat Enzyme, because it is known that the mechanisms for the up-regulation of COX-1 and COX-2 activities in vivo are different. For instance, in a situation where PGI2 is only required for a short term in the circulation, the COX-2 based Trip-cat Enzyme could be preferred.

It is known that the C-terminal amino acid sequence of human COX-1 is different with that of human COX-2 [16]. The crystal structures of the COX-1 C-terminal domain are not available yet. Therefore, it remains a challenge to clearly define its orientation in respect to the ER membrane, which may affect the ER retention and anchoring, as well as enzyme catalytic functions. The active Trip-cat Enzyme-1 was prepared by linking the human COX-1 C-terminus to the PGIS N-terminus through a 10-residue TM linker. The fact that this linkage did not affect the COX-1 catalytic function is consistent with earlier studies, in which the COX-1 activity was not affected by elongation of the C-terminal segment [16]. The linkage also configured the COX-1 C-terminus on the membrane of the ER lumen in the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 (Figure 1). Our data (Figure 2ii) have clearly indicated that catalytic activity and ER anchoring were not affected by this configuration. It implies that the C-terminus is likely to be located close to the ER membrane in the native COX-1. Another Whether the C-terminal structure is related to the COX-1 stable expression in the cells remains a challenging question to be explored.

Recently, Smith’s group reported that the recombinant COX-1 (t1/2 > 24 hr), expressed in HEK293 cells, happens to be more stable than that of the COX-2 (t1/2 approximately 5 hr), and found that a unique 19-amino acid cassette in the C-terminal region of COX-2 facilitates degradation of the expressed COX-2 in the cells [17]. Without the 19-amino acid cassette in the COX-1 sequence, the expressed COX-1 maintains a higher expression level and activity level in the cells in comparison to that of COX-2. This finding has provided a partial explanation for the improved activity and stable expression of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 derived from the COX-1. In addition, the 26 S proteosome inhibitors retarded the COX-2 degradation, but not COX-1 in cells [16]. This has indicated that COX-2 is easily degraded in the cells, which could be another key factor that would lead to more difficulty in creating a stable expression of COX-2-10aa-PGIS in the cells. However, the exact involvement of the gene regulation for the different expression levels of the COX-1- and COX-2- derived Trip-cat Enzymes remains to be further characterized.

One of the major difficulties in using membrane protein as a therapeutic agent is the limited amount of options currently available for solubilizing and purifying the protein. Non-ionic detergent is commonly used for solubilizing and purifying the membrane proteins, but is not suitable for experiments requiring admission of the membrane protein in vivo. One way to deliver the membrane protein in vivo is to introduce engineered cells which specifically overexpress the target protein, (COX-1-10aa-PGIS “Trip-cat Enzyme-1”). The successful establishment of an HEK293 cell line that can stably overexpress the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 and constantly produce active PGI2, while demonstrating strong anti-platelet aggregation properties, has provided a model for generating a therapeutic cell line for potential therapeutic use of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in vivo.

Anti-platelet aggregation assays provide an important method that confirms the benefits of the newly engineered Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in anti-thrombosis function. Human platelet cells are rich in COX-1 and TXAS. Following the AA released from the cell membrane (via stimuli on the platelets), the majority of the AA is converted to TXA2 by the coupling reaction of COX-1 and TXAS. The resultant TXA2 binds to its receptor on the surface of the platelet and causes platelet aggregation. The inhibition of the platelet aggregation by the HEK293 cells stably expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 (Figure 6i) has strongly indicated that: 1) The expressed Trip-cat Enzyme-1 was able to compete with the endogenous COX-1 and use AA as a substrate; 2) The PGH2 produced by the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 was readily available to the PGIS active site, even in the presence of TXAS, which competitively binds to the PGH2; and 3) The immediate increase in PGI2 production by the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 reduced the amount of PGH2 available for TXAS to produce TXA2 (Figure 7), which further prevented platelet aggregation. These factors have led the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 to possess dual functions: increasing PGI2 and reducing TXA2 biosynthesis, which could be a unique and novel anti-thrombosis and anti-ischemic approach that has not yet been available thus far. In addition, the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 also showed significant activity in inhibiting non-AA induced aggregation (Figure 7B), such as that of collagen. This indicated that the HEK293 cells stably expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 could use endogenous AA in the plasma,,diffused from the platelets, to produce PGI2 against platelet aggregation. Furthermore, this suggests the therapeutic potential of the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 in anti-platelet aggregation through cell delivery.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

HEK293 cell line was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Medium for culturing the cell lines was purchased from Invitrogen. [14C]-AA was purchased from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ). Goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC conjugate, saponin, streptolysin O, Triton X-100, and triethylenediamine were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Mowiol 4–88 was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

Cell Culture

HEK293 cells were cultured in a 100-mm cell culture dish with high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotic and antimycotic) and were grown at 37° C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Engineered cDNA Plasmids with Single Genes Encoding the Human COX-1 and PGIS Sequences

The sequence of COX-1 linked to PGIS through a 10 amino acid (10aa) linker (COX-1-10aa-PGIS, Trip-cat Enzyme-1) was generated by a PCR approach and subcloning procedures provided by the vector company (Invitrogen). The procedures have been previously described [13].

Transient and Stable Expression of the Trip-cat Enzymes in Cells

The recombinant Trip-cat Enzyme-1 and -2 were expressed in HEK293 cells using the pcDNA3.1 vector. Briefly, the cells were grown and transfected with the purified cDNA of the recombinant protein by the Lipofectamine 2000 method [13] following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). For the transient expression, the cells were harvested approximately 48 hrs after transfection for further enzyme assays and Western blot analysis. For the stable expression, the transfected cells were cultured in the presence of geneticin (G418 screening) for several weeks following the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). The cells stably expressing the Trip-cat Enzyme-1 and -2 were identified by enzyme assay and Western blot analysis.

Enzyme Activity Determination for the Trip-cat Enzymes Using the HPLC Method

To determine the activities of the synthases that converted AA to PGI2 through the triple catalytic functions, different concentrations of [14C]-AA (0.2–17.5 µM) were added to the HEK293 expressing either the Trip-cat Enzyme-1, or co-expressing COX-1 and PGIS enzymes, or to the non-transfected cells in a total reaction volume of 100 µL. After 10 sec to 15 min of incubation, the reactions were terminated by adding 200 µL of the solvent containing 0.1% acetic acid and 35% acetonitrile (solvent A). After centrifugation (12000 rpm for 5 min), the supernatant was injected into a C18 column (Varian Microsorb-MV 100-5, 4.6 × 250 mm) using the solvent A with a gradient from 35 to 100% of acetonitrile for 45 min at a flow-rate of 1.0 mL/min. The 14C-labeled AA metabolites, including 6-keto-PGF1α (degraded PGI2) were monitored directly by a flow scintillation analyzer (Packard 150TR).

Immunofluorescence Staining

The stable/transiently transfected HEK293 cells expressing either the Trip-cat Enzyme-1, the co-expressed COX-1 and PGIS enzymes, or the vector (pcDNA 3.1) alone, were cultured on a cover glass. The cells were then washed with PBS and incubated, either with 0.5 mU SLO for 10 min or with 1% saponin for 20 min. Afterward, the cells were incubated with the primary antibody (10 µg/mL, affinity-purified anti- human PGIS or anti-mouse COX-1 antibody) for 1 hr. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with the FITC- or rhodamine-labeled secondary antibodies [13, 18] and viewed under a Fluorescence microscope.

Anti-Platelet Aggregation Assays

A sample of fresh blood was collected using a collection tube with 3.2% sodium citrate for anticoagulation, and then centrifuged to separate the plasma from the red blood cells. A total of 450 µL of this platelet rich plasma was placed inside the 37° C incubator of an aggregometer (Chrono-Log) for 3 minutes. The non-transfected HEK293 cells as well as those transfected with the recombinant cDNAs of COX-1-10aa-PGIS (Trip-cat Enzyme-1) or the co-expressed COX-1 and PGIS were added into different tubes containing platelet rich plasma. The sample was then treated with 500 µg/mL arachidonic acid, while inside the platelet aggregometer's incubator, to initiate the aggregation process. Readings by the anticoagulant analyzer were obtained indicating the amount of platelet aggregation inhibited by each of the treated samples.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH Grants (HL56712 and HL79389 (to KHR)). In addition, we thank Drs. Richard Kulmacz and Lee-Ho Wang for providing the original wild type cDNAs of human COX-1 and PGIS, respectively.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- AA

arachidonic acid

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- PGI2

prostacyclin

- PGIS

prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin) synthase

- TXA2

Thromboxane A2

- TXAS

Thromboxane A2 synthase

REFERENCES

- 1.Majerus PW. Arachidonate metabolism in vascular disorders. J. Clin. Invest. 1983;72:1521–1525. doi: 10.1172/JCI111110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pace-Asciak CR, Smith WL. Enzymes in the biosynthesis and catabolism of the eicosanoids: prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes and hydroxy fatty acids. Enzymes. 1983;16:544–604. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samuelsson B, Goldyne M, Granstrom E, Hamberg M, Hammarstrom S, Malmsten C. Prostaglandins and thromboxanes. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1978;47:994–1030. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.005025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith WL. Prostaglandin biosynthesis and its compartmentation in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1986;48:251–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng Y, Austin SC, Rocca B, Koller BH, Coffman TM, Grosser T, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Role of prostacyclin in the cardiovascular response to thromboxane A2. Science. 2002;296:539–541. doi: 10.1126/science.1068711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vane JR. Biomedicine. Back to an aspirin a day? Science. 2002;296:474–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1071702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith WL, Song I. The enzymology of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002 Aug;:68–69. 115–128. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 8 Needleman P, Turk J, Jackschik BA, Morrison AR, Lefkowith JB. Arachidonic acid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1986;55:69–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunting S, Gryglewski R, Moncada S, Vane JR. Arterial walls generate from prostaglandin endoperoxides a substance (prostaglandin X) which relaxes strips of mesenteric and coeliac arteries and inhibits platelet aggregation. Prostaglandins. 1976;12:897–913. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moncada S, Herman AG, Higgs EA, Vane JR. Differential formation of prostacyclin (PGX or PGI2) by layers of the arterial wall. An explanation for the anti-thrombotic properties of vascular endothelium. Thromb. Res. 1977;11:323–344. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(77)90185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weksler BB, Ley CW, Jaffe EA. Stimulation of endothelial cell prostacyclin production by thrombin, trypsin, and the ionophore A 23187. J. Clin. Invest. 1978;62:923–930. doi: 10.1172/JCI109220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruan KH, Deng H, So SP. Engineering of a protein with cyclooxygenase and prostacyclin synthase activities that converts arachidonic acid to prostacyclin. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14003–14011. doi: 10.1021/bi0614277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruan KH. Hybrid protein that converts arachidonic acid into prostacyclin. WO Patent. 2007 doi: 10.1021/bi0614277. WO/2007/104000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okada T, Palczewski K. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: implications for vision and beyond. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:420–426. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Q, Kulmacz RJ. Distinct influences of carboxyl terminal segment structure on function in the two isoforms of prostaglandin H synthase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;384:269–279. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbonye UR, Wada M, Rieke CJ, Tang HY, Dewitt DL, Smith WL. The 19-amino acid cassette of cyclooxygenase-2 mediates entry of the protein into the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35770–35778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin YZ, Deng H, Ruan KH. Topology of catalytic portion of prostaglandin I(2) synthase: identification by molecular modeling-guided site-specific antibodies. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;379:188–197. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]