The personal effects of prostatectomy on intimacy and sexual satisfaction as seen through the eyes of a professional couple (a young physician cancer survivor and his spouse, who has a doctorate in counseling psychology) have not previously been expressed in the literature. We believe that because of our unique situation we can provide a few concrete recommendations for family physicians as they relate to patients and their spouses before and after surgery.

We can state with absolute conviction that, despite our backgrounds and education, we were totally unprepared for the challenges of maintaining our relationship while learning to deal with the loss of sexual intimacy forced on us by prostatectomy. After consultation with the top treatment centres in the United States, we decided that nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy was the best treatment decision. We realize in retrospect that our real trauma occurred because our expectations of sexual recovery drastically differed from what the treatment team believed constituted success. The physical recovery from the procedure brought no real indication of how much our lives would be changed. This would include grief at the loss of intimacy, changes in relational dynamics, misguided individual expectations, a lack of interpersonal communication, and a lack of professional data to help us. This unguided process of the recovery of sexual function resulted in our pursuing many treatment directions with mostly poor results, until frustration nearly left us without hope of intimacy. Only after a serious period of reflection did we realize that we lacked the individual coping skills to bring our relationship back to a place where a new normalcy could be established.

Stage of life

We recently conducted a literature review on sexual dysfunction after prostatectomy. This led us to the article by Anne Katz1 and the accompanying editorial by Peter Pommerville2 in the July 2005 issue of Canadian Family Physician. Both authors presented the medical facts about treatment options and the effects on sexual potency succinctly, and their comments remain current.

More recent literature reveals that there is considerable variation according to age and life stage in satisfaction regarding sexual intimacy after radical prostatectomy. Owing to recent advances, more patients are being diagnosed at earlier ages, with potentially greater odds of surgical cure.3

There is a great need for family physicians to recognize the reality of both the physical and psychological differences among prostatectomy patients at different life stages.3 The literature supports that expectations and concerns about prostatectomy vary among age groups, and in fact the potential for sexual dysfunction might be the greatest determining factor in treatment choice in men younger than age 60.3 Unfortunately, younger patients who have the greatest need for surgical cure might suffer the most in terms of how sexual dysfunction affects intimate relationships.

Data on success rates of cancer treatment and medical treatment of sexual dysfunction after prostatectomy are very limited for young patients. Little new information is available for those younger than 50 years of age, and this set of patients reports the highest distress related to sexual dysfunction.4 Despite the increasing prevalence of younger patients, they report the greatest difficulties in obtaining help for sexual problems, and spousal involvement in the process is rare.5 Presurgical consultations tend to focus on success rates of cancer treatment and statistical representations of complication rates, including erectile dysfunction. In our opinion such statistics do not provide any true expectation of outcome, nor are the life changes that occur adequately addressed. Many patients feel betrayed when they finally face the reality of their changed sexual function (usually 1 or more years after surgery) and they frequently regret their treatment decisions.6

Younger patients and their partners definitely experience the greatest stress and have the highest rates of dissatisfaction with what treating physicians define as “successful” outcomes. Issues such as loss of penile length or girth, for example, might be much more troublesome for those couples younger than 60 years of age than those of more advanced age. Additionally, although oral agents might be sufficient to provide a satisfactory erection for penetration, this does not mean that it is sufficient for a mutually satisfying sexual experience.6 Changes in ejaculation can be very disturbing, especially when coupled with the loss of ejaculatory and orgasm control many men experience after prostatectomy.2 Furthermore, the use of injections or vacuum devices can negatively affect a couple’s satisfaction owing to loss of spontaneity and uncertainty about effectiveness. Persistent attempts and experiments might lead to frustration, awkwardness, and despair, promoting feelings of anger, guilt, and anxiety, which can cause further deterioration in intimacy. The literature confirms that loss of erectile function is directly linked to a male’s perception of masculinity, and few men have any understanding of the effect that impotency would have on their self-image.4

In our review we found that the psychological literature appeared to be much more in touch with the issues affecting postoperative patients and their partners and it appeared better prepared to provide guidance related to issues of sexual dysfunction in younger age groups.5,7,8 The literature identifies considerable effects on feelings of well-being, self-esteem, and relationship difficulties, particularly in younger patients who have undergone prostatectomy, and problems with depression, feelings of isolation, and social withdrawal have been reported.4

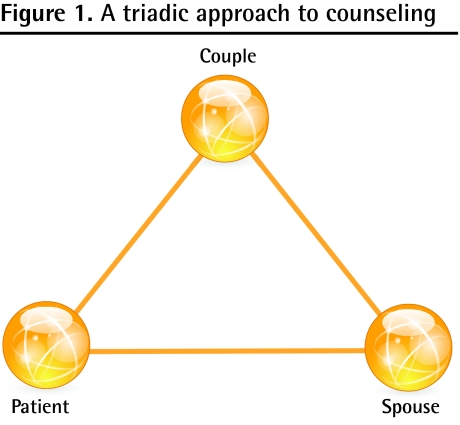

Mental health interventions need to be instituted in a triadic formation (Figure 1), where each partner is counseled separately, and as a couple. Individually, each needs a supportive, reality-based approach before and after surgery. Family physicians need to understand the independent needs of all 3 components—the patient, the spouse, and the couple—before recommending specific interventions. In reviewing these studies, it was clear that additional research is needed, as current studies have small sample sizes, limitations in patient reporting and study methods, and cultural influences.

Figure 1.

A triadic approach to counseling

Role of family physicians

In our opinion family physicians are potentially the greatest resource available to prostatectomy patients before and after surgery with regard to interventions for sexual dysfunction and intimacy issues. As a former family practitioner (C.M.) and a mental health counselor (A.N.M.), we are well aware of the difficulties in being able to provide appropriate guidance and medical management to a variety of patients, particularly in light of the multiple demands on physician time.

We recommend that family physicians do the following in an effort to support this group of patients:

Identify a local or regional referral resource for psychological and sexual counseling, and recommend evaluation for all prostatectomy patients before and after surgery, not only those who present with postsurgical difficulties.

Become familiar with treatments of erectile dysfunction, other than oral agents, and identify a referral provider who specializes in advanced treatment of erectile dysfunction.

Be aware that individual and couple counseling might be more successful in assisting a couple in the long term with intimacy issues, and referral to centres that provide a multidisciplinary approach should always be considered. It is our hope that sharing this very personal journey will in some way benefit similar couples when dealing with the unavoidable issues caused by this disease. Now, 5 years after surgery, we can attest to the tremendous difficulties encountered. Given our educational backgrounds, perhaps it should have been easy for us to obtain both medical and psychological treatment, but it was not. The advanced medical treatment available is rarely disseminated outside major centres, and multidisciplinary approaches are only now being embraced. We encourage all providers to be extremely honest with prostatectomy patients and their spouses about expectations of the surgical outcome as well as the expectant return to sexual intimacy and the need for a new normalcy.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de février 2011 à la page e37.

Competing interests

None declared

The opinions expressed in commentaries are those of the authors. Publication does not imply endorsement by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

References

- 1.Katz A. What happened? Sexual consequences of prostate cancer and its treatment. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:977–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pommerville PJ. From bedside to bed. Recovery of sexual function after prostate cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:941–3. 948–50. Eng. (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harden H, Nothhouse L, Cimprick B, Pohl JM, Liang J, Kershaw T. The influence of developmental life stage on quality of life in survivors of prostate cancer and their partners. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(2):84–94. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0048-z. Epub 2008 Mar 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthew AG, Goldman A, Trachtenberg J, Robinson J, Horsburgh S, Currie K, et al. Sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: prevalence, treatments, restricted use of treatments and distress. J Urol. 2005;174(6):2105–10. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181206.16447.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neese LE, Schover LR, Klein EA, Zippe C, Kupelian PA. Finding help for sexual problems after prostate cancer treatment: a phone survey of men’s and women’s perspectives. Psychooncology. 2003;12(5):463–73. doi: 10.1002/pon.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray RE, Fitch MI, Phillips C, Labracque M, Fergus K, Klotz L. Prostate cancer and erectile dysfunction: men’s experiences. Int J Mens Health. 2002;1(1):15–29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manne S, Babb J, Pinover W, Horwitz E, Ebbert J. Psychoeducational group intervention for wives of men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(1):37–46. doi: 10.1002/pon.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penedo FJ, Antoni MH, Scheiderman N. Cognitive-behavioral stress management for prostate cancer recovery. New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]