Abstract

Objective

To describe the prevalence of patients who screen positive for symptoms of bipolar disorder in primary care practice using the validated Mood Disorders Questionnaire (MDQ).

Design

Prevalence survey.

Setting

Fifty-four primary care practices across Canada.

Participants

Adult patients presenting to their primary care practitioners for any cause and reporting, during the course of their visits, current or previous symptoms of depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Main outcome measures

Subjects were screened for symptoms suggestive of bipolar disorder using the MDQ. Health-related quality of life, functional impairment, and work productivity were evaluated using the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey and Sheehan Disability Scale.

Results

A total of 1416 patients were approached to participate in this study, and 1304 completed the survey. Of these, 27.9% screened positive for symptoms of bipolar disorder. All 13 items of the MDQ were significantly associated with screening positive for bipolar disorder (P < .05). Patients screening positive were significantly more likely to report depression, anxiety, substance use, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, family history of bipolar disorder, or suicide attempts than patients screening negative were (P < .001). Health-related quality of life, work or school productivity, and social and family functioning were all significantly worse in patients who screened positive (P < .001).

Conclusion

This prevalence survey suggests that more than a quarter of patients presenting to primary care with past or current psychiatric indices are at risk of bipolar disorder. Patients exhibiting a cluster of these symptoms should be further questioned on family history of bipolar disorder and suicide attempts, and selectively screened for symptoms suggestive of bipolar disorder using the quick and high-yielding MDQ.

Résumé

Objectif

Présenter la prévalence de patients des soins primaires chez qui un dépistage à l’aide du Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) a révélé des symptômes de trouble bipolaire.

Type d’étude

Enquête de prévalence.

Contexte

Cinquante-quatre cliniques de soins primaires au Canada.

Participants

Patients adultes qui consultaient leurs soignants de première ligne pour une raison quelconque et qui mentionnaient au cours de leur visite des symptômes présents ou passés de dépression, anxiété, consommation de drogue ou de trouble de déficit de l’attention/hyperactivité.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

On a utilisé le MDQ pour dépister chez les sujets les symptômes de trouble bipolaire. La qualité de vie en lien avec la santé, les déficits fonctionnels et la productivité au travail ont été évalués au moyen du Short-Form Health Survey à 12 items et de la Sheehan Disability Scale.

Résultats

Sur 1416 patients invités à participer, 1304 ont répondu à l’enquête. Parmi ces patients, 27,9 % ont montré des symptômes de trouble bipolaire au dépistage. Les 13 items du MDQ montraient tous une association significative avec le fait d’avoir un dépistage positif pour le trouble bipolaire (P < ,05). Les patients qui avaient un dépistage positif étaient significativement plus susceptibles que les autres de rapporter de la dépression, de l’anxiété, de la consommation de drogue, un trouble de déficit de l’attention/hyperactivité, une histoire familiale de trouble bipolaire ou une tentative de suicide (P < ,001). La qualité de vie en lien avec la santé, la productivité au travail ou à l’école, et le fonctionnement social et familial étaient tous significativement moins bons chez ceux qui avaient un dépistage positif (P < ,001).

Conclusion

Cette enquête de prévalence suggère que plus d’un quart des patients qui consultent dans une clinique de soins primaires avec des indices psychiatriques passés ou présents sont à risque de souffrir de trouble bipolaire. Les patients qui présentent plusieurs de ces symptômes devraient être davantage questionnés sur une histoire familiale de trouble bipolaire et de tentative de suicide, et soumis à un dépistage des symptômes suggestifs d’un trouble bipolaire à l’aide du MDQ, un questionnaire bref et très performant.

Bipolar disorder is a considerable mental health concern, with an estimated lifetime prevalence rate of 2.2%.1 This severe and chronic illness is associated with substantial morbidity, mediated in part by the high rate of psychiatric2,3 and medical4–6 comorbidities. Up to 65% of patients with bipolar disorder meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, criteria for at least 1 comorbid lifetime axis I disorder,2 which can complicate diagnosis and treatment.7 The most common psychiatric comorbidities are anxiety disorder (lifetime prevalence of 51%), which predicts an earlier age of onset of bipolar disorder and a more complicated and severe disease course; substance use disorder (61% for bipolar I disorder and 48% for bipolar II disorder), which complicates treatment options; attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which has a bidirectional relationship with bipolar disorder (ADHD occurs in up to 85% of children with bipolar disorder, and bipolar disorder occurs in up to 22% of children with ADHD); and personality disorders (prevalence of about 33%). These psychiatric comorbidities are reviewed in detail by Sagman and Tohen.8

Bipolar disorder also has a substantial effect on patient functioning and quality of life. Compared with the general population, patients with bipolar disorder are 4 times and 8 times more likely to receive low physical and mental quality of life component scores, respectively.9 Patients with bipolar disorder suffer from moderate to severe psychosocial impairment 26% to 31% of the time, and severe impairment of work function 20% to 30% of the time,10 underscoring the personal and societal cost of this illness. Psychosocial impairment is particularly affected during depressive phases of bipolar illness, and increases substantially with worsening levels of depressive symptom severity.11 Suicidal behaviour in bipolar disorder is among the highest of any mental illness, with up to 80% of patients reporting suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts over their lifetimes.12

Patients with bipolar disorder most commonly present to their primary care physicians, and they present more often during episodes of depression than mania or hypomania.13,14 Yet primary care physicians do not routinely screen patients with depressive episodes for a history of mania or hypomania,15 despite the availability of an easy-to-use screening tool for bipolar symptoms called the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ).16,17 Although the MDQ is not a diagnostic tool for bipolar disorder, it is a validated instrument that screens for a lifetime history of manic or hypomanic symptoms. Using the MDQ, Das et al reported that 1 in 10 patients presenting to an American urban general medicine clinic screened positive for a lifetime history of manic or hypomanic symptoms.18 Among those patients screening positive, less than 10% had been previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder,18 supporting evidence from other studies that this condition might be underdiagnosed in primary care despite its relatively high prevalence.19,20

In the study by Das et al, patients were more likely to screen positive for bipolar disorder if they had concurrent symptoms of suicidal thoughts (4.8 times more likely), drug use disorder (4.3 times more likely), alcohol use disorder (3.7 times more likely), panic disorder (3.2 times more likely), major depression (2.9 times more likely), or generalized anxiety disorder (2.8 times more likely) compared with patients without these symptoms.18 An estimated 9% to 35% of adults with bipolar disorder have a current or childhood history of ADHD,21–24 suggesting that a history of ADHD might also lead to a higher index of suspicion of bipolar disorder. These factors that are highly associated with bipolar disorder could therefore be used to select patients in primary care who should be screened for symptoms of bipolar disorder. Positive family history has also been shown to be highly associated with bipolar disorder.25

This prevalence study was conducted to screen for lifetime bipolar disorder symptoms among adult patients with the above associated psychiatric symptoms in primary care practices across Canada using the MDQ; assess the associated risks of these other psychiatric symptoms with screening positive for bipolar symptoms; and examine their effects on functional disability, work productivity, and quality of life.

METHODS

Study design

A convenience sample of primary care practitioners (PCPs), stratified by region, was recruited to participate. In total, 244 PCPs were invited and 54 agreed. Forty-six PCPs successfully enrolled subjects in the study. Their average duration of practice was 25 years (range 8 to 43). Ethics approval was obtained. All patient participants provided written informed consent. Data were collected from December 3, 2007, to May 9, 2008.

Inclusion criteria

A consecutive sample of patients aged 18 to 65 years who presented to their PCPs for care for any cause but who also reported, during the course of their visits, current or previous symptoms (of any intensity or duration, treated or untreated) of depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, or ADHD were approached for participation. For the purpose of this study, depressive symptoms were defined as irritable mood, loss of interest or pleasure, sleep disturbance, loss of energy, fatigue, inability to concentrate, or feelings of guilt. Anxiety symptoms were defined as excessive worry, palpitations, feeling “keyed up,” sleep disturbance, irritability, obsessions, compulsions, recurrent flashbacks, or being easy to startle. Substance use disorder was defined as alcohol, street, or prescription drug abuse or gambling. History of ADHD was documented from the patient file or patient history.

Patients with previously diagnosed bipolar disorder were excluded.

Each PCP was asked to collect data on 25 patients and keep a log of the number of patients who were approached to participate, refusals, and patients who were prescreened but found to be ineligible. On average, each PCP enrolled 24 patients (range 2 to 140).

Sample size

The sample size was estimated to provide a standard error of 1.1% to 1.3% for the expected prevalence of lifetime bipolar disorder, estimated to be 15% to 20% based on data from a previous study.18 The sample size was also estimated to detect a minimum average difference in the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) physical health summary score of 2.9 (95% confidence interval [CI] of 0.7 to 5.2) and mental health summary score of 3.5 (95% CI 1.5 to 5.6),18 using a 2-sided t test with power of 90% and a false-positive error rate of 0.0125 (including a Bonferroni correction). Assuming that 85% of eligible participants would consent to participate and a 90% completion rate for the MDQ and SF-12 questionnaires,18 the required sample size was calculated to be 1202.

Survey

For patients meeting eligibility criteria and consenting to participate, PCPs collected demographic information including sex, age, and employment status. Patients then independently completed 3 surveys: the MDQ, the SF-12, and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). The PCPs tabulated completed questionnaires, and the case report forms were faxed to a central location where they were encrypted in transit and converted to digital documents for analysis.

An 8-page case report form including the 4 survey instruments, which took approximately 15 to 30 minutes to complete, was used. Translated versions of the surveys were available for use in French-speaking regions: the MDQ and SDS were translated in-house and verified by a French-speaking PCP participating in the study, and the licensed French version of the SF-12 was used.

Screening for bipolar disorder

Participants were screened using the MDQ, a single-page inventory that screens for a lifetime history of manic or hypomanic symptoms using 13 yes-or-no questions derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, criteria and from clinical experience.26 The level of functional impairment due to symptoms of mania or hypomania is assessed using a 4-point scale from “no problem” to “serious problem.” Standard MDQ scoring for bipolar disorder requires endorsement of at least 7 lifetime manic or hypomanic symptoms, several co-occurring symptoms, and moderate or serious associated functional impairment. The MDQ has a reported sensitivity of 28% and a specificity of 97% in a community sample,26 and a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 90% in an outpatient psychiatric sample.16 In the current study, participants who met or exceeded the standard MDQ scoring algorithm were considered to have screened positive for bipolar disorder.

Functional disability and health-related quality of life

Physical and mental health functioning were based, respectively, on the physical and mental component summary scores of the SF-12.27 Impairment was evaluated with the SDS.28–31 Substantial impairment for each SDS subscale was defined by a rating of 7 or higher. The effect of symptoms on work productivity was also assessed using 2 self-reported questions.

Statistical analysis

The overall prevalence of screening positive for lifetime symptoms of bipolar disorder was estimated with a 95% CI assuming an underlying binomial distribution. Rates of positive screening were calculated by demographic characteristics, and the related associations assessed using χ2 tests. Proportions of positive responses to individual MDQ items and their 95% CIs were displayed by screening outcomes.

The association between screening positive and symptom presentation was evaluated using χ2 tests. Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratios of screening positive for presenting symptoms, family history of bipolar disorder, and history of suicide attempts. The odds ratio estimates were adjusted for age, sex, education, and geographic location. Because presenting symptoms were relatively common (> 10%), the corresponding relative risk estimates are better risk summary measures.32 The odds ratio estimates from logistic regression were converted to relative risk estimates.

Health functioning and work productivity were compared between screening groups using t tests and impairment was compared using χ2 tests. Analysis of variance with similar adjusting factors was used to estimate the adjusted change scores between screening groups. Logistic regression analysis was also used to derive relative risk estimates of having severe impairments between the groups.

RESULTS

Response rate

A total of 1416 patients were approached to participate in the study; of these 54 (3.8%) declined to participate. An additional 62 patients (4.5%) were excluded from the analysis because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (54 were older than 65 years; 1 was younger than 18 years; and 7 had no presenting symptoms).

Demographics

Of 1304 participants who completed the surveys, 770 (59%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 42.5 (12.2) years. They resided in British Columbia (6.7%); Alberta, Saskatchewan, or Manitoba (39.9%); Ontario (25.1%); Quebec (18.6%); or Atlantic Canada (10.6%). Slightly more than half (53.3%) had some college or university education. Participants reported whether they worked full-time (46.2%) or part-time (19.5%), were not working (22.0%), or were receiving disability benefits (12.2%).

Prevalence of symptoms of bipolar disorder

A total of 27.9% (95% CI 25.5% to 30.3%) of the participants screened positive for a lifetime history of bipolar disorder symptoms (Table 1). The prevalence did not vary significantly by sex or region but did vary significantly with age and education level (P < .001). There was a trend toward a higher incidence of positive screening in patients who were not working or were receiving disability benefits, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Table 1.

Rates of screening positive for lifetime bipolar disorder symptoms stratified by demographic characteristics: 364 of the 1304 participants (27.9%) screened positive.

| VARIABLE N/N (%) | PARTICIPANTS WHO SCREENED POSITIVE | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | .11 | |

| • Female | 202/770 (26.2) | |

| • Male | 162/534 (30.3) | |

| Age, y | < .001 | |

| • 18–44 | 228/697 (32.7) | |

| • 45–54 | 95/364 (26.1) | |

| • 55–65 | 41/243 (16.9) | |

| Education | < .001 | |

| • High school or lower | 195/595 (32.8) | |

| • College | 109/373 (29.2) | |

| • University or postgraduate | 57/306 (18.6) | |

| Work status | .055 | |

| • Working full-time (≥ 40 h/wk) | 154/597 (25.8) | |

| • Working part-time (< 40 h/wk) | 62/252 (24.6) | |

| • Not working | 91/284 (32.0) | |

| • Receiving disability benefits | 53/158 (33.5) | |

| Region | .19 | |

| • British Columbia | 24/88 (27.3) | |

| • Prairies | 148/507 (29.2) | |

| • Ontario | 100/327 (30.6) | |

| • Quebec | 53/243 (21.8) | |

| • Atlantic provinces | 39/139 (28.1) |

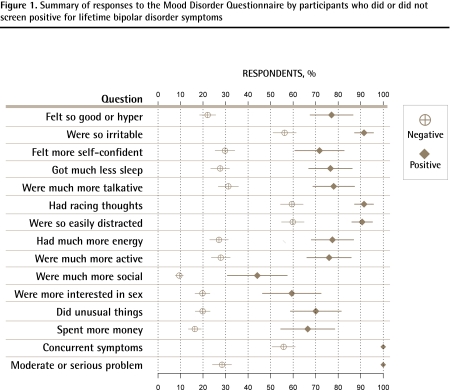

The symptoms elicited by all 13 items in the first question of the MDQ were significantly (P < .05) more prevalent among participants screening positive than among those screening negative (Figure 1). Participants who screened positive were on average 46.8% (range 30.8% to 55.0%) more likely to report these 13 symptoms. The MDQ requires concurrency of several symptoms for participants to screen positive for symptoms of bipolar disorder. Even among those who screened negative, 55.8% reported concurrent symptoms. Similarly, these concurrent symptoms needed to be a moderate or serious problem for participants to screen positive. Only 27.8% of participants screening negative reported concurrent symptoms to be a moderate or serious problem.

Figure 1.

Summary of responses to the Mood Disorder Questionnaire by participants who did or did not screen positive for lifetime bipolar disorder symptoms

Presenting symptoms

Participants were more than 3.5 times more likely to report depression and anxiety symptoms than substance use disorders, history of ADHD, family history of bipolar disorder, or history of suicide attempt (Table 2). Despite their high frequency, and after adjusting for relevant baseline characteristics, the presence of depression or anxiety symptoms was significantly associated with screening positive for symptoms of bipolar disorder (adjusted relative risk [95% CI] for depression 1.14 [1.08 to 1.17] and anxiety 1.11 [1.05 to 1.15]). However, the less prevalent symptoms were much more discriminatory compared with depression and anxiety symptoms: participants with family history of bipolar disorder were 2.28 (95% CI 1.77 to 2.89) times more likely to screen positive than those without family history; those with history of substance use disorders were 1.84 (95% CI 1.45, 2.27) times more likely to screen positive, and those with history of suicide attempts or ADHD were approximately 2 times more likely to screen positive.

Table 2.

Presenting psychiatric symptoms among participants who did or did not screen positive for lifetime bipolar disorder symptoms

| SYMPTOMS | ALL PARTICIPANTS (N = 1304*), N (%) | PARTICIPANTS WHO SCREENED POSITIVE (N = 364*), N (%) | PARTICIPANTS WHO SCREENED NEGATIVE (N = 940*), N (%) | UNADJUSTED P VALUE | ADJUSTED RELATIVE RISK† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression‡ | 1127 (88.5) | 335 (95.2) | 792 (82.5) | < .001 | 1.14 (1.08 to 1.17) |

| Anxiety§ | 1067 (82.8) | 332 (89.2) | 745 (80.3) | < .001 | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.15) |

| Addiction|| | 313 (24.5) | 151 (41.5) | 162 (17.7) | < .001 | 1.84 (1.45 to 2.27) |

| History of ADHD | 154 (11.9) | 75 (20.7) | 79 (8.5) | < .001 | 1.97 (1.31 to 2.87) |

| Family history of bipolar disorder | 224 (17.3) | 110 (30.4) | 114 (12.1) | < .001 | 2.28 (1.77 to 2.89) |

| History of suicide attempts¶ | 254 (19.5) | 131 (36.1) | 123 (13.1) | < .001 | 2.06 (1.59 to 2.62) |

Denominators vary owing to missing data.

Logistic regression adjusting for age, sex, education, and region. Adjusted odds ratio was converted to relative risk using the prevalence observed in participants who screened negative.

Depression was defined by symptoms including irritable mood, loss of interest or pleasure, sleep disturbance, loss of energy, fatigue, inability to concentrate, or feelings of guilt.

Anxiety was defined by symptoms including excessive worry, palpitations, feeling “keyed up,” sleep disturbance, irritability, obsessions, compulsions, recurrent flashbacks, or being easy to startle.

Addiction to alcohol, street or prescription drugs, or gambling.

History of suicide attempts recorded by primary care practitioner as yes or no.

Health functioning, impairment, and work loss

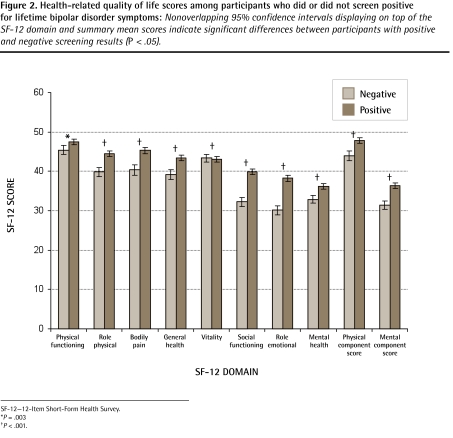

Mental and physical health-related quality of life based on the SF-12 mental and physical component scores were significantly (P < .001) lower (worse) for participants who screened positive for bipolar disorder symptoms than those who screened negative (Table 3). These measures remained lower after controlling for age, sex, education, and region. Among participants who screened positive for symptoms of bipolar disorder, the SF-12 quality of life domains that were significantly (P < .05) and negatively affected were emotional functioning, social functioning, and bodily pain, among others (Figure 2). Significant impairments for work or school, social, and family life functioning were significantly more common among participants who screened positive than negative (P < .001). Participants who screened positive for symptoms of bipolar disorder incurred significantly (P < .001) more days lost from their normal daily responsibilities or more days underproductive at school or work, compared with those who screened negative (Table 3).

Table 3.

Health functioning, impairment, and work loss among participants who did or did not screen positive for lifetime bipolar disorder symptoms: A) Health functioning and work loss; B) impairment.

| A) | ||||

| MEASURE | PARTICIPANTS WHO SCREENED POSITIVE (N = 364) MEAN (SD) | PARTICIPANTS WHO SCREENED NEGATIVE (N = 940) MEAN (SD) | UNADJUSTED P VALUE* | ADJUSTED CHANGE SCORE (95% CI)† |

| Health functioning‡ | ||||

| • SF-12 mental health component score | 31.41 (10.42) | 36.37 (11.87) | < .001 | −4.48 (−5.89 to −3.07) |

| • SF-12 physical health component score | 43.90 (11.88) | 47.84 (11.72) | < .001 | −4.08 (−5.49 to −2.67) |

| Work loss§ | ||||

| • Days lost in the past week | 1.60 (2.37) | 1.09 (2.03) | < .001 | 0.41 (0.14 to 0.68) |

| • Days underproductive in the past week | 2.92 (2.51) | 1.88 (2.53) | < .001 | 0.95 (0.66 to 1.24) |

| B) | ||||

| MEASURE | SCREENED POSITIVE (N = 364) N (%) | SCREENED NEGATIVE (N = 940) N (%) | UNADJUSTED P VALUE* | ADJUSTED RELATIVE RISK (95% CI)† |

| Impairment|| | ||||

| • Work or school | 247 (67.86) | 392 (41.70) | < .001 | 1.64 (1.50 to 1.77) |

| • Social | 245 (67.31) | 308 (32.77) | < .001 | 2.08 (1.89 to 2.24) |

| • Family life or home responsibilities | 238 (65.38) | 310 (32.98) | < .001 | 2.00 (1.82 to 2.18) |

SF-12—12-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

Unadjusted t test for continuous variables or χ2 test for binomial variables.

Analysis of covariance adjusting for age, sex, and education.

SF-12 health-related quality of life.

Days lost or underproductive in the past week related to the disorder.

Impairment defined as a subscale score of ≥ 7 (marked or extreme impairment) on the work, social, and family life subscales of the Sheehan Disability Scale. For the work subscale, data from participants who had not worked or studied at all during the past week for reasons unrelated to the disorder were excluded.

Figure 2.

Health-related quality of life scores among participants who did or did not screen positive for lifetime bipolar disorder symptoms: Nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals displaying on top of the SF-12 domain and summary mean scores indicate significant differences between participants with positive and negative screening results (P < .05).

SF-12—12-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

*P = .003

†P < .001.

DISCUSSION

This study found an estimated lifetime prevalence of symptoms suggestive of bipolar spectrum disorder of 27.9% among a sample of patients presenting to primary care practices across Canada, with indices of depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorders, or current or past ADHD. This is substantially higher than the prevalence of 9.8% reported by Das et al, who used the MDQ to assess the lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder symptoms in a consecutive sample of patients seeking primary care services for any medical complaint in a single American family practice unit.18 It is, however, consistent with the results by Manning et al, who reported that 25.9% of 108 consecutive patients with depressive or anxiety disorders assessed by a physician in a single family care practice had a lifetime history of mania or hypomania.33 Correctly distinguishing between unipolar and bipolar depression is of clinical importance, as an inappropriate treatment regimen might be instituted if bipolar disorder is mistaken for unipolar depression. Treatment of bipolar disorder patients with unopposed antidepressants might precipitate a manic or hypomanic episode34,35 or induce rapid cycling,36,37 which is associated with poorer prognosis and response to treatment.38

The results of this prevalence survey suggest that a quick, high-yield screening approach could be used in the primary care setting to identify patients with symptoms of bipolar disorder who require follow-up investigation. Because the MDQ is a nondiagnostic screening tool, further evaluation to formally diagnose bipolar disorder is warranted in patients who screen positive on the MDQ. In our survey population, more than 1 in 4 patients presenting to their PCPs with indices of depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorders, or ADHD screened positive for a lifetime history of bipolar symptoms using the validated MDQ. Our survey data also suggest the expansion of the above psychiatric indices to include family history of bipolar disorder and history of suicide attempts. This is in accordance with studies suggesting that family history is highly predictive of bipolar disorder, with a heritability of 0.73 (bipolar I disorder) to 0.77 (bipolar II disorder).39 Patients presenting with a cluster of these 6 indices should therefore be screened for bipolar symptoms with the MDQ and followed accordingly.

The MDQ has been widely used as a screening tool for symptoms of bipolar disorder, and is now considered the criterion standard.40–44 In our study, the MDQ was highly sensitive for identifying patients with symptoms of bipolar disorder in a population of patients presenting with symptoms of depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorders, or ADHD. Most notable were the high discriminatory differences among participants who screened positive and negative with respect to the 13 symptomatic items in the first question of the MDQ. These symptoms are more likely to be concurrent and substantially more problematic for patients who screened positive than for those who screened negative using the MDQ. Data from these items are useful not only for the MDQ assessment but also for guiding the follow-up management of the disorder, including appropriate diagnosis. The MDQ provides a method to quickly assess the concurrency of indices suggestive of bipolar disorder and their associated severity. The questionnaire can be self-administered, then easily scored and reviewed by a health care professional.

Bipolar disorders have considerable negative effects on patient quality of life, psychosocial function, and work performance, and are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.9–11 Further, data suggest that bipolar disorder can go unrecognized for up to 7 to 10 years.45,46 Many patients do not achieve full recovery from their symptoms and continue to experience considerable impairment in social and work activities,10,47 even during periods of euthymia.48,49 Das et al reported that patients who screened positive for bipolar disorder symptoms also experienced significant disability in health, social, family, and occupational functioning (P ≤ .001).18 Our observational data suggest that patients who screened positive for bipolar symptoms had significantly poorer health-related quality of life than those who screened negative (P < .05). Indeed, the observed reduction in SF-12 physical and mental health summary scores in participants screening positive was much greater than the corresponding scores reported previously in patients seeking care for any reason and without specific psychiatric indices.18

In this study, patients who screened positive for bipolar symptoms also had significantly more days classified as underproductive. These impairments remained significant even after adjusting for age, sex, education, and region. This underscores the importance of screening high-risk patients who are not yet diagnosed with bipolar disorder but who are at risk of the condition, so that earlier diagnosis and institution of appropriate treatment might improve their overall quality of life and functioning.

This study did not assess the relative contributions of the symptoms of bipolarity versus the comorbid symptoms (eg, depressive, anxiety, substance abuse, or ADHD) on quality of life and work productivity. Therefore, the observed relations are assumed to be due to the presence of both the bipolar symptoms and the reported comorbid symptoms.

Limitations

We selected for patients with psychiatric indices known to be associated with bipolar disorder. Therefore, the risk of bipolarity in the general primary care patient population cannot be extrapolated from these data. In addition, PCPs who participated might have had an interest in psychiatry, and therefore might have been more perceptive of patients presenting with symptoms of depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorders, and ADHD. Finally, the MDQ was self-administered by patients and might overestimate the number of patients with a lifetime history of manic or hypomanic symptoms, compared with a structured diagnostic assessment.

Conclusion

Our survey demonstrates that more than one-quarter of patients presenting to primary care practices across Canada, with current or past psychiatric symptoms or ADHD, screened positive for symptoms suggestive of bipolar disorder using a simple screening approach. A high risk of lifetime bipolar disorder symptoms was strongly associated with a cluster of psychiatric indices, including depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorders, and ADHD. Further predictors of screening positive were family history of bipolar disorder and suicide attempt. Patients who screened positive for bipolar disorder symptoms exhibited substantial impairment in quality of life, social and family functioning, and work productivity. Therefore, the MDQ could be used to selectively screen patients at high risk of bipolar symptoms in primary care. Further studies evaluating the efficacy of this screening approach to identify patients who could benefit from appropriate diagnosis and timely intervention are warranted.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Patients with bipolar disorder most commonly present to their primary care physicians, and they present more often during episodes of depression than mania or hypomania; this study found an estimated lifetime prevalence of symptoms suggestive of bipolar spectrum disorder of 27.9% among a sample of patients presenting to primary care practices across Canada and exhibiting indices of depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorders, or current or past attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Patients who screened positive for bipolar disorder symptoms exhibited substantial impairment in quality of life, social and family functioning, and work productivity.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire has been widely used as a screening tool for symptoms of bipolar disorder and is now considered the criterion standard. It could be used to selectively screen patients at high risk of bipolar symptoms in primary care.

Treatment of patients with bipolar disorder with unopposed antidepressants might precipitate manic or hypomanic episodes or induce rapid cycling, which is associated with poorer prognosis and response to treatment.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Les patients souffrant de trouble bipolaire consultent généralement leur médecin de première ligne, et ce, plus souvent lors d’épisodes de dépression que lors d’épisodes de manie ou d’hypomanie; dans cette étude, on a trouvé une prévalence à vie de symptômes suggestifs de trouble bipolaire estimée à 27,9 % dans un échantillon de patients qui ont consulté dans une clinique de soins primaires au Canada et qui présentaient des signes de dépression, d’anxiété, de consommation de drogues ou de trouble déficit de l’attention/hyperactivité passé ou présent.

Les patients avec un dépistage positif pour des symptômes de trouble bipolaire montraient une diminution importante de leur qualité de vie, de leur fonctionnement social et familial, et de leur productivité au travail.

Le Mood Disorder Questionnaire est abondamment utilisé comme outil de dépistage pour les symptôme du trouble bipolaire et on le considère maintenant comme le critère standard. Il pourrait être utilisé en médecine primaire pour le dépistage sélectif des patients à risque élevé de symptômes bipolaires.

Le fait de traiter des patients bipolaires avec des antidépresseurs sans stabilisateur de l’humeur pourrait déclencher des épisodes de manie ou d’hypomanie, ou induire une accélération des cycles, ce qui s’accompagne d’un pronostic et d’une réponse au traitement moins favorables.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Drs Chiu and Chokka contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Schaffer A, Cairney J, Cheung A, Veldhuizen S, Levitt A. Community survey of bipolar disorder in Canada: lifetime prevalence and illness characteristics. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(1):9–16. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Jr, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, et al. Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(3):420–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer MS, Altshuler L, Evans DR, Beresford T, Williford WO, Hauger R, et al. Prevalence and distinct correlates of anxiety, substance, and combined comorbidity in a multi-site public sector sample with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;85(3):301–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Soczynska JK, Wilkins K, Panjwani G, Bouffard B, et al. Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: implications for functional outcomes and health service utilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1140–4. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiedorowicz JG, Palaqummi NM, Forman-Hoffman VL, Miller DD, Haynes WG. Elevated prevalence of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk factors in bipolar disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20(3):131–7. doi: 10.1080/10401230802177722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soreca I, Fagiolini A, Frank E, Houck PR, Thompson WK, Kupfer DJ. Relationship of general medical burden, duration of illness and age in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(11):956–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.10.009. Epub 2008 Feb 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151489.36347.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagman D, Tohen M. Comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Times. 2009;26(4):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Gurpegui M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Gutiérrez-Ariza JA, Ruiz-Veguilla M, Jurado D. Quality of life in bipolar disorder patients: a comparison with a general population sample. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(5):625–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Solomon DA, Maser JD, Coryell W, Endicott J, et al. Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1–2):49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.014. Epub 2007 Nov 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA, et al. Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: a prospective, comparative, longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(12):1322–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valtonen H, Suominen K, Mantere O, Leppämäki S, Arvilommi P, Isometsä ET. Suicidal ideation and attempts in bipolar I and II disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(11):1456–62. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manning JS, Connor PD, Sahai A. The bipolar spectrum: a review of current concepts and implications for the management of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(1):63–71. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manning JS. All that wheezes is not asthma: bipolar disorder in primary care 1997–2007. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(2):89–90. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, Carlson CA. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(4):233–9. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, Calabrese JR, Flynn L, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1873–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, Weissman M, Reed M, Davies M, et al. Validity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a general population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):178–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky DJ, Blanco C, Feder A, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care clinic. JAMA. 2005;293(8):956–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.8.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.López J, Baca E, Botillo C, Quintero J, Navarro R, Negueruela M, et al. Diagnostic errors and temporal stability in bipolar disorder [Article in Spanish] Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2008;36(4):205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschfeld RM, Calabrese JR, Weissman MM, Reed M, Davies MA, Frye MA, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in the community. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(1):53–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamam L, Tuglu C, Karatas G, Ozcan S. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with bipolar I disorder in remission: preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60(4):480–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Spencer T, Wisniewski SR, Otto MW, Simon N, et al. Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime attention-deficit/hyper-activity disorder comorbidity in adults with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamam L, Karaku G, Ozpoyraz N. Comorbidity of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder: prevalence and clinical correlates. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(7):385–93. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0807-x. Epub 2008 Apr 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sentissi O, Navarro JC, De Oliveira HD, Gourion D, Bourdel MC, Baylé FJ, et al. Bipolar disorders and quality of life: the impact of attention deficit/hyper-activity disorder and substance abuse in euthymic patients. Psychiatry Res. 2008;161(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.06.016. Epub 2008 Sep 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Schaffer A, Parikh SV, Beaulieu S, O’Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2009. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(3):225–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams JW, Jr, Pignone M, Ramirez G, Perez Stellato C. Identifying depression in primary care, a literature synthesis of case-finding instruments. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(4):225–37. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan DV. The anxiety disease. New York, NY: Charles Scribner and Sons; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL. Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: the Sheehan Disability Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27(2):78–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00788510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(2):93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning JS, Radwan FH, Connor PD, Akiskal HS. On the nature of depressive and anxious states in a family practice setting: the high prevalence of bipolar II and related disorders in a cohort followed longitudinally. Compr Psychiatry. 1997;38(2):102–8. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boerlin HL, Gitlin MJ, Zoellner LA, Hammen CL. Bipolar depression and antidepressant-induced mania: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(7):374–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howland RH. Induction of mania with serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16(6):425–7. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199612000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(10):804–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wehr TA, Goodwin FK. Can antidepressants cause mania and worsen the course of affective illness? Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(11):1403–11. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.11.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altshuler LL, Post RM, Leverich GS, Mikalauskas K, Rosoff A, Ackerman L. Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(8):1130–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edvardsen J, Torgersen S, Røysamb E, Lygren S, Skre I, Onstad S, et al. Heritability of bipolar spectrum disorders. Unity or heterogeneity? J Affect Disord. 2008;106(3):229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.001. Epub 2007 Aug 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Twiss J, Jones S, Anderson I. Validation of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for screening for bipolar disorder in a UK sample. J Affect Disord. 2008;110(1–2):180–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.235. Epub 2008 Feb 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber Rouget B, Gervasoni N, Dubuis V, Gex-Fabry M, Bondolfi G, Aubry JM. Screening for bipolar disorders using a French version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) J Affect Disord. 2005;88(1):103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez-Moreno J, Villagran JM, Gutierrez JR, Camacho M, Ocio S, Palao D, et al. Adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for the detection of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(3):400–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker G, Fletcher K, Barrett M, Synnott H, Breakspear M, Hyett M, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder: the utility and comparative properties of the MSS and MDQ measures. J Affect Disord. 2008;109(1–2):83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.003. Epub 2008 Feb 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calabrese JR, Muzina DJ, Kemp DE, Sachs GS, Frye MA, Thompson TR, et al. Predictors of bipolar disorder risk among patients currently treated for major depression. MedGenMed. 2006;8(3):38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RM. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord. 1994;31(4):281–94. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chion AM, Pandurangi AK, Goodwin K. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52(1–3):135–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldberg JF, Harrow M. Consistency of remission and outcome in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders: a 10-year prospective follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2004;81(2):123–31. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malhi GS, Ivanovski B, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Mitchell PB, Vieta E, Sachdev P. Neuropsychological deficits and functional impairment in bipolar depression, hypomania and euthymia. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(1–2):114–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mur M, Portella MJ, Martínez-Arán A, Pifarré J, Vieta E. Long-term stability of cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder: a 2-year follow-up study of lithium-treated euthymic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):712–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]