Abstract

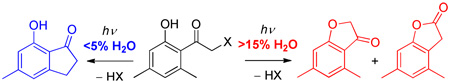

A clean bifurcation between two important photochemical reactions through competition of a triplet state Type II H-abstraction reaction with a photo-Favorskii rearrangement for (o/p)-hydroxy-o-methylphenacyl esters that depends on the water content of the solvent has been established. The switch from the anhydrous Type II pathway that yields indanones to the aqueous-dependent pathway producing benzofuranones occurs abruptly at low water concentrations (~8%). The surprisingly clean yields suggest that such reactions are synthetically promising.

An intramolecular Type II reaction of alkylphenones, especially 2-methylacetophenoes, produces high yields of photoenols that have been shown to be valuable reactive intermediates.1 When a leaving group (X) is present in the α-position of 2-alkylacetophenones (1), longer-lived (E)-photoenols liberate HX to give indanones2 (2; Scheme 1) that can be employed as precursors to elaborate products used in synthetic methodology.3 Likewise, the photo-Favorskii rearrangement of α-substituted p-hydroxyacetophenones (3) to p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4), discovered more recently, has enjoyed success in a variety of applications because of its rapid release of nucleofuges (Scheme 1).4 Both reactions have exhibited very good photochemical efficiencies and are relatively free of side reactions that produce complicated product mixtures. The similarity of the chromophores, the common triplet state origin for reaction, and the extensive understanding of the mechanistic photochemistry5 have prompted us to explore the intersection of the photochemical pathways to uncover which parameters control the pathway followed by a chromophore common to both.

Scheme 1.

Photochemistry of Phenacyl Derivatives

It is a rare occurrence in organic photochemistry when one can completely and cleanly divert the reaction or rearrangement pathway from a single product type to an alternative pathway yielding an entirely different structure by addition of H2O to the solvent.3a Since it is well known that electron donating hydroxy and methoxy groups suppress Type II reactivity6 and nearly as well known that the photo-Favorskii rearrangement has a strong affinity for water,4k,7 we assumed that these two reaction pathways might be separated by the water content of the solvent media. In this work, the analogs of 4-hydroxyphenacyl derivatives with good leaving groups necessary for the photo-Favorskii process were fitted with 2-methyl substituent for efficient Type II hydrogen abstraction reaction to compete with the photo-Favorskii rearrangement. As an extension, a similar design, in which the 2-hydroxyphenacyl derivatives were fitted with a 6-methyl group, was also examined.

Synthesis of Phenacyl Esters

4-Hydroxy-2-methyl (9a–c) and 2-hydroxy-4,6-dimethylphenacyl (14) esters, and the corresponding benzyl (10) and methyl (13) ethers were prepared by α-bromination of acetophenones 5, 6 and 11 and then SN2 reaction with formate, acetate, benzoate, or mesylate (Scheme 2). Overall yields ranged from 18% to 50%.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Hydroxy-2-methylphenacyl Esters

A Comparison of the Photochemistry of 2- and 4-Hydroxy-o-methylphenacyl Esters (9a–c, 14), and Their Benzyl (10) and Methyl Ethers (13b)

Solutions (~10 mM) of each of the phenacyl esters in a series of solvents were irradiated at λ = 300 or 313 nm until more than 95% of the starting material had disappeared. All of the esters released the corresponding acid in nearly quantitative yield. The hydroxyphenacyl chromophores were transformed into two distinct solvent-dependent sets of rearranged photoproducts (Scheme 3; Tables 1 and 2). Indanones (17 and 19) were formed in low water (<5%) content acetonitrile or benzene. In methanol, 9 gave a complex mixture of unidentified products, which may be due to photoaddition of methanol to the enol.3a The ethers 10 and 13b gave only the indanone products (18 and 22) in all solvents; benzocyclobutanol 23 was produced only from 13b. In contrast, 2-methyl-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid 15 and 2-methyl-4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol 16 were formed from 9, while 4,6-dimethylbenzofuran-3(2H)-one 20 and 4,6-dimethylbenzofuran-2(3H)-one 21 were produced from 14 in aqueous-based solutions.

Scheme 3.

Photochemistry of 9a–c, 10, 13b, and 14

Table 1.

Photoproducts Formed by Irradiation of 9a–c and 10

| compound | solvent (ratio) | chemical yields / % a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 16 | 17 or 18 | ||

| 9a | H2O/CH3CN (3:1) | 79 | 8 | – b |

| 9b | H2O/CH3CN (3:1) | 82 | 8 | – b |

| 9c | H2O/CH3CN (3: 1) | 80 (80 c) | 9 | – b |

| CH3CN or C6H6 | – b | – b | 80 d (17) | |

| 10 | H2O/CH3CN (1:1) | – b | – b | >80 d (18) |

| C6H6 | – b | – b | 84 d (18) | |

Irradiated at λ = 300 nm in non-degassed solutions to >95% conversion; the chemical yields were determined by 1H NMR and are the average of two measurements.

Not observed.

Isolated yield as the methyl ester of 15 (see Supporting Information).

Indanones 17 and 18 decompose under prolonged irradiation.

Table 2.

Photoproducts from Irradiation of 14 and 13b

| compound | solvent (ratio) | chemical yields / % a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 or 22 | 20 | 21 | 23 | ||

| 14 | benzene | 59 (19) | 9 | 8 | – b |

| CH3OH | – b | 28 | 62 | – b | |

| CH3CN | 60 (19) | 5 | 9 | – b | |

| H2O/CH3CN (1:1) | – b | 30 | 55 | – b | |

| 13b | benzene | 79 (22) | – b | – b | – b |

| CH3CN | 65 (22) | – b | – b | 15 | |

| H2O/CH3CN (1:1) | 41 (22) | – b | – b | 13 | |

Degassed solutions irradiated at λ = 300 nm to >95% conversion. Isolated yields; the average of two measurements.

Not observed.

What is clearly apparent is the remarkable influence that water plays in changing the course from classic Type II photochemistry to the photo-Favorskii rearrangement. Phenylacetic acid (15), as established earlier,4a,4c and dimethylbenzofuranones 20 and 21, in this study, were formed via the photo-Favorskii rearrangement, whereas the indanones 17, 18, 19, and 22 were apparently derived from classic Type II photoenolization2a,b,8 (Scheme 1 and 3).

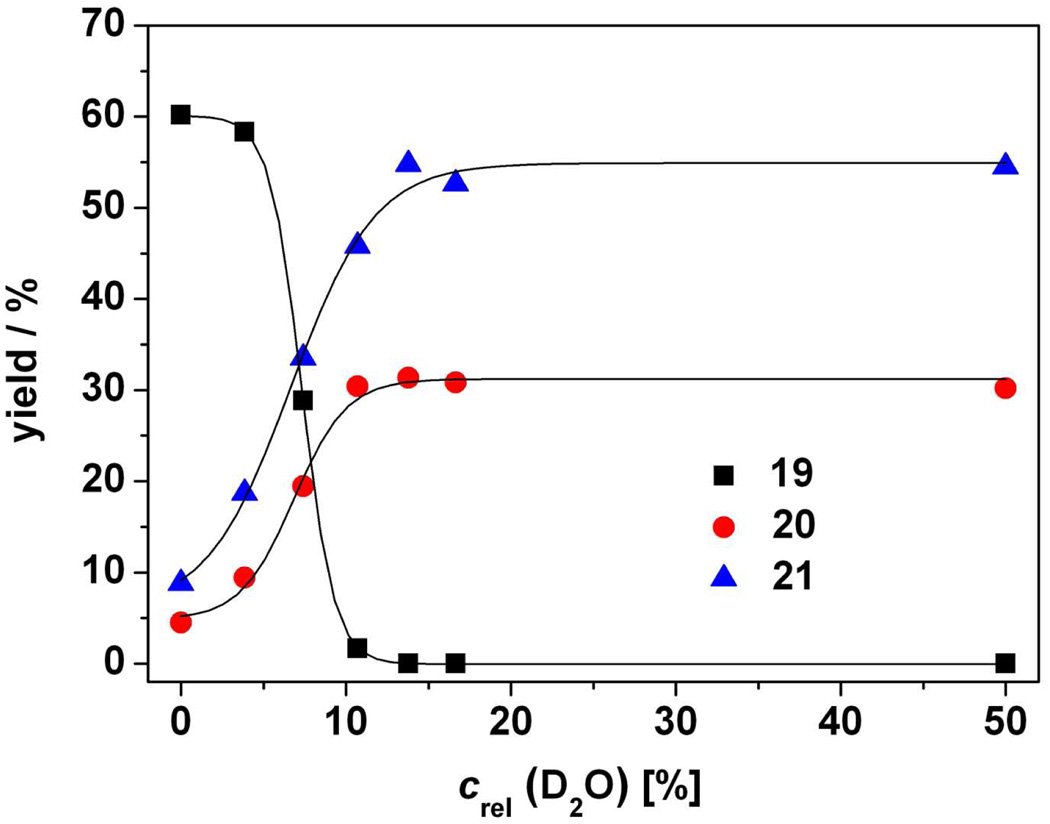

Figures 1 and 2 further demonstrate that the two competing pathways can be “titrated” by careful addition of water to the reaction media in the photolysis of 9c and 14. With 9c, the reaction efficiencies of the two competing processes coalesced at ~8% aq acetonitrile and 15 and 16 became the sole products when water content reached ~30% in degassed solutions. It is noteworthy that for the irradiations of 14, the crossover point from the Type II process to photo-Favorskii, where 20/21 replaces 19 as the dominant pathway, was nearly the same.

Figure 1.

Yields of 15 ( ) and 17 (■) obtained by irradiation of 9c in aq acetonitrile at λ = 313 nm. The photochemical conversions were kept between 50 and 70% in all solvent mixtures (and 30% in acetonitrile to avoid secondary reactions). The standard deviation of the mean for each point was <10%.

) and 17 (■) obtained by irradiation of 9c in aq acetonitrile at λ = 313 nm. The photochemical conversions were kept between 50 and 70% in all solvent mixtures (and 30% in acetonitrile to avoid secondary reactions). The standard deviation of the mean for each point was <10%.

Figure 2.

Yields of 19 (■), 20 ( ), and 21 (

), and 21 ( ) determined by 1H NMR from irradiation of 14 in aqueous acetonitrile at λ = 313 nm to > 90% conversion. The standard deviation of the mean for each point was <10%.

) determined by 1H NMR from irradiation of 14 in aqueous acetonitrile at λ = 313 nm to > 90% conversion. The standard deviation of the mean for each point was <10%.

Anhydrous Media: The Photoenolization Pathway

Photoenolization to isomeric (E)- and (Z)-dienols from 2-alkylphenones is a well–established, triplet state pathway.1,5 Strategic positioning of a leaving group α to the carbonyl (1, Scheme 1) sets the stage for an elimination cascade from the (E)-photoenol, whereas the (Z)-isomer rapidly reverts to the alkylphenone via 1,5-sigmatropic hydrogen transfer. The (E)-photoenol’s longer lifetime is sufficient to permit the release of modest to very good nucleofuges2,8 generating primarily indanone 2 (Scheme 1) in non-aqueous and nonnucleophilic solvents.3a As expected, the presence of either the o- or p-hydroxy groups on 14 (Scheme 4) and 9, respectively, did not influence the dominance of the photoenol pathway. The compounds 10 and 13b, in which the photo-Favorskii pathway was suppressed by replacing the hydroxy with an alkoxy group, also followed the photoenolization pathway. Cyclobutanol 23 along with indanone 22 were formed from 13b in dry or aqueous acetonitrile, apparently via photoenol 25 (Scheme 4) similar to the cyclobutanols produced from 2,4,6-trialkylphenacyl benzoates.9

Scheme 4.

Photo-Favorskii and Photoenolization Intermediates

Phenyl ketones are known to have two nearly isoenergetic triplet states and their relative energies are strongly influenced by both the aryl substituents and the solvent.10 Electron-donating substituents and polar solvents tend to stabilize the π,π* state,11 which is generally far less reactive toward H-atom abstraction than the n,π* state with its half vacant, non-bonding p orbital on the carbonyl oxygen.6 To our surprise, 14, having three electron donating substituents (and largely a π,π* configuration), still underwent photoenolization in acetonitrile, although the reaction was much less efficient (by a factor of 10 compared with those carried out in aqueous organic solvents).

Aqueous Media: Photo-Favorskii Pathway

In stark contrast to photoenolization, photo-Favorskii rearrangements4b,c,4g,4i–k of the 2-alkyl-4-hydroxyphenacyl derivatives 9a–c, bearing the nucleofuge α to the carbonyl, formed 15 when photolyzed in mixed aqueous organic solvents (Scheme 1). Givens, Wirz, and coworkers recently recounted the vital role that water plays in this rearrangement.4h,4k The process relies on a triplet state proton loss from the hydroxy group to solvent water, which is thought to be in concert with solvent assisted release of the nucleofuge forming a triplet biradical intermediate. The biradical relaxes to a putative spirodienedione intermediate (Scheme 1) that either opens to the phenylacetic acid or loses CO to form a quinomethane.

The fact that this process dominates when the water content is significant is not surprising. Both photo-Favorskii and photoenolization transformations are primarily triplet reactions. A triplet lifetime of τ = 340–770 ps4k was reported for the 4-hydroxyphenacyl carboxylate analogs, which is nearly an order of magnitude shorter than the triplet (τ ~ 3 ns2c) invoked for photoenolization of 2,5-dimethylphenacyl carboxylate. This would imply that the reaction of 9c in water should favor the photo-Favorskii process. Therefore, decreasing the solvent water content disfavors the photo-Favorskii process and encourages photoenolization which is largely independent of the presence of water.

Even more intriguing are the pathways for formation of 20 and 21. They were formed in parallel (generally 21 dominates) as the major products in aqueous solvents, although a small amount was also observed in anhydrous solvents (Table 2). We posit that, based on the analogy with the photo-Favorskii reaction, the putative spirodienedione intermediate 26 serves as a common intermediate for both 20 and 21 in the irradiation of 14 (Scheme 4). The proposed ring expansion of the cyclopropanone by nucleophilic attack of the cyclohexadienone carbonyl on either one of the benzylic bonds (blue and red bond scissions) but predominantly on the one attached to the cyclopropanone carbonyl (blue scission) leads to the two products. The rearrangement of 26 to 20 and 21 does not require large amounts of water, i.e. the water assisted ring opening as seen for formation of 15 from 9a–c is overridden by the intramolecular nature of this novel rearrangement step. These processes are currently under investigation in our laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Support for this work was provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic: ME09021 (KONTAKT/AMVIS) and MSM0021622413, the project CETOCOEN (CZ.1.05/2.1.00/01.0001) granted by the European Regional Development Fund, the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic: 203/09/0748 (PS, PK), Dongguk University (Seoul Campus) (BSP), and the NIH grants GM069663 and R01 GM72910 (RSG).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details and characterization data for products are provided. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Haag R, Wirz J, Wagner PJ. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1977;60:2595. [Google Scholar]; (b) Das PK, Encinas MV, Small RD, Scaiano JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:6965. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Klan P, Zabadal M, Heger D. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1569. doi: 10.1021/ol005789x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pelliccioli AP, Klan PP, Zabadal M, Wirz J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7931. doi: 10.1021/ja016088d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zabadal M, Pelliccioli AP, Klan P, Wirz J. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:10329. doi: 10.1021/ja016088d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Klan P, Pelliccioli AP, Pospisil T, Wirz J. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2002;1:920. doi: 10.1039/b208171g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Literak J, Wirz J, Klan P. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2005;4:43. doi: 10.1039/b408851d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kammari L, Plistil L, Wirz J, Klan P. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007;6:50. doi: 10.1039/b612233g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Plistil L, Solomek T, Wirz J, Heger D, Klan P. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8050. doi: 10.1021/jo061169j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pospisil T, Veetil AT, Antony LAP, Klan P. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008;7:625. doi: 10.1039/b719760h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Solomek T, Stacko P, Veetil AT, Pospisil T, Klan P. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:7300. doi: 10.1021/jo101515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wessig P, Glombitza C, Muller G, Teubner J. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:7582. doi: 10.1021/jo040173x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Givens RS, Park CH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:6259. [Google Scholar]; (b) Givens RS, Jung A, Park CH, Weber J, Bartlett W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:8369. [Google Scholar]; (c) Park CH, Givens RS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:2453. [Google Scholar]; (d) Conrad PG, Givens RS, Hellrung B, Rajesh CS, Ramseier M, Wirz J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9346. [Google Scholar]; (e) Conrad PG, Givens RS, Weber JFW, Kandler K. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1545. doi: 10.1021/ol005856n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Givens RS, Weber JFW, Conrad PG, Orosz G, Donahue SL, Thayer SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2687. [Google Scholar]; (g) Givens RS, Heger D, Hellrung B, Kamdzhilov Y, Mac M, Conrad PG, Cope E, Lee JI, Mata-Segreda JF, Schowen RL, Wirz J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3307. doi: 10.1021/ja7109579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Stensrud KF, Heger D, Sebej P, Wirz J, Givens RS. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008;7:614. doi: 10.1039/b719367j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Ma CS, Kwok WM, Chan WS, Du Y, Kan JTW, Toy PH, Phillips DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2558. doi: 10.1021/ja0532032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Ma CS, Kwok WM, Chan WS, Zuo P, Kan JTW, Toy PH, Phillips DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1463. doi: 10.1021/ja0458524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Stensrud K, Noh J, Kandler K, Wirz J, Heger D, Givens RS. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:5219. doi: 10.1021/jo900139h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klan P, Wirz J. Photochemistry of Organic Compounds: From Concepts to Practice. 1st ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2009. p. 584. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner PJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1971;4:168. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Dhavale DD, Mali VP, Sudrik SG, Sonawane HR. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:16789. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones G, McDonnell LP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:6203. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergmark WR. J. Chem. Soc.-Chem. Commun. 1978;61 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park BS, Ryu HJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:1512. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Wagner PJ, Park B-S. Photoinduced Hydrogen Atom Abstraction by Carbonyl Compounds. In: Padwa A, editor. Organic Photochemistry. Vol. 11. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1991. p. 227. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wagner PJ, Klan P. Norrish Type II Photoelimination of Ketones: Cleavage of 1,4-Biradicals Formed by a-Hydrogen Abstraction. In: Horspool WM, Lenci F, editors. CRC Handbook of Organic Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2nd ed. Chap. 52. Boca Raton: CRC Press LLC; 2003. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Rauh RD, Leermakers PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:2246. doi: 10.1021/ja01027a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li YH, Lim EC. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1970;7:15. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.