Abstract

Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) by the highly toxic, prototypical ligand, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-para-dioxin (TCDD) or other dioxin-like compounds compromises ovarian function by altering follicle maturation and steroid synthesis. Although alteration of transcription after nuclear translocation and heterodimerization of AhR with its binding partner, aryl hydrocarbon nuclear transporter (ARNT), is often cited as a primary mechanism for mediating the toxic effects of dioxins, recent evidence indicates that crosstalk between AhR and several other signaling pathways also occurs. Like the circadian clock genes, AhR is a member of the basic helix-loop-helix, Per-ARNT-SIM (bHLH-PAS) domain family of proteins. Thus, these studies tested the hypothesis that TCDD can act to alter circadian clock regulation in the ovary. Adult female c57bl6/J mice entrained to a typical 12 h light/12 h dark cycle were exposed to a single 1 µg/kg dose of TCDD by gavage. Six days after exposure, animals were released into constant darkness and ovaries were collected every 4 h over a 24 h period. Quantitative real-time PCR and immunoblot analysis demonstrated that TCDD exposure alters expression of the canonical clock genes, Bmal1 and Per2 in the ovary. AhR transcript and protein, which displayed a circadian pattern of expression in the ovaries of control mice, were also altered after TCDD treatment. Immunohistochemistry studies revealed co-localization of AhR with BMAL1 in various ovarian cell types. Furthermore, co-immunoprecipitation demonstrated time-of-day dependent interactions of AhR with BMAL1 that were enhanced after TCDD treatment. Collectively these studies suggest that crosstalk between classical AhR signaling and the molecular circadian clockworks may be responsible for altered ovarian function after TCDD exposure.

Keywords: AhR, Circadian Rhythm, BMAL1, PER2, Ovary

1. Introduction

Dioxins and dioxin-like compounds are toxicants, detrimental to biological systems, that are produced as unwanted by-products of industrial processes (Kulkarni et al., 2008). The most potent of the dioxins, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), is formed from combustion processes, during chlorine bleaching of paper-products and in the production of pesticides and herbicides. The resistance of TCDD to metabolism, as well as its lipophilic chemical nature, contributes to bioaccumulation in animals and humans, as well as biomagnification within the ecosystem. Its half-life can be more than 10 years in humans (Aylward et al., 2005). Human TCDD exposure at low levels commonly occurs through the consumption of contaminated meats and dairy products (Travis and Hattemer-Frey, 1991). Toxic effects of TCDD include teratogenesis, immune impairment, carcinogenesis, and developmental and reproductive dysfunction (Birnbaum, 1994; Pohjanvirta et al., 1994).

TCDD exposure causes compromised ovarian function through alteration of follicle development, alteration of steroidogenesis and inhibition of ovulation (Petroff et al., 2001). A single acute exposure to TCDD causes estrous cycle irregularity and a reduction in the ovulation rate in adult, cycling rats (Li et al., 1995a). TCDD alters levels of both gonadotropins and ovarian steroid hormones, and reduces ovulation in the gonadotropin-primed immature rat model (Li et al., 1995b). Effects of TCDD on ovarian function are likely mediated indirectly through the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, as well as directly at the level of the ovary (Hernandez-Ochoa et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2004; Petroff et al., 2001).

TCDD acts primarily through high affinity binding and activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (Beischlag et al., 2008). In the absence of ligand, AhR resides in the cell cytoplasm bound to heat shock protein 90, p23 and Ara9 (Petrulis and Perdew, 2002). Binding to TCDD or other ligands induces a conformational change in AhR, revealing a nuclear localization signal and promoting translocation to the nucleus, where AhR is released to partner with aryl hydrocarbon nuclear transporter (ARNT); the AhR/ARNT heterodimer acts as a transcription factor at specific promoter sites identified as dioxin response elements (DRE) to regulate the expression of target genes (Denison et al., 1989). Of particular toxicological relevance is the activation of various xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes, including the P450 enzymes CYP1A1, 1A2 and 1B1 (Kleiner et al., 2004; Nebert et al., 2004; Nebert et al., 1993). Although transcriptional activation of target genes is a major mechanism for AhR-dependent functions, mounting evidence demonstrates that numerous other pathways may be influenced by activation of AhR (Pocar et al., 2005). TCDD activates protein tyrosine kinases leading to changes in protein phosphorylation (Enan and Matsumura, 1995), and mobilizes internal calcium stores (Puga et al., 1997) in a transcriptionally-independent manner. AhR cross-talk with steroid hormone pathways, growth factor signaling and the cell cycle highlight the diverse and complex actions of AhR in the cell (Pocar et al., 2005; Puga et al., 2009).

AhR is a founding member of the PER-ARNT-SIM (PAS) domain family of transcriptional regulators. Typically, PAS domain-containing proteins act as environmental and/or physiological sensors to direct changes through protein-protein interactions and ultimately through alteration of gene expression. An analysis of intron/exon splice patterns of PAS domain-containing proteins reveals significant similarities between the canonical circadian clock gene, BMAL1 (brain and muscle ARNT-like) and AhR (Yu et al., 1999). Typically, BMAL1 forms a heterodimer with CLOCK (Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles Kaput) to drive circadian rhythms. However, PAS domain proteins are notoriously promiscuous, forming various alternative pairs (Hogenesch et al., 1998; Probst et al., 1997). BMAL1 interacts with AhR in vitro (Hogenesch et al., 1997) and in vivo (Xu et al., 2010). Recent evidence suggests that there are reciprocal interactions between AhR signaling and the circadian clock. Activation of AhR inhibits the clock gene Per1 (Garrett and Gasiewicz, 2006; Xu et al., 2010), and AhR signaling is modified when Per1 is suppressed (Qu et al., 2007, , 2009; Qu et al., 2010).

The molecular components of a functional circadian clock are present in the mammalian ovary (Fahrenkrug et al., 2006; Karman and Tischkau, 2006). Ovarian clock gene expression is regulated by gonadotropins and ovarian steroids (He et al., 2007b; Karman and Tischkau, 2006; Nakamura et al., 2010; Petrulis and Perdew, 2002; Tischkau et al., 2011). Although the function of the clockworks in the ovary remains ambiguous, circadian control of steroidogenesis and cell proliferation are apparent (He et al., 2007a, 2007b; Ratajczak et al., 2009). Recently, our laboratory has demonstrated that activation of AhR with TCDD or β-napthoflavone (BNF) alters circadian rhythms in the central clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, as well as in the liver (Mukai et al., 2008; Mukai and Tischkau, 2007; Xu et al., 2010). This study was designed to examine the hypothesis that alteration of circadian rhythmicity contributes to the mechanism by which TCDD exerts its effects on the ovary.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals and TCDD Exposure

Adult female c57bl6/J mice (2 months of age) were obtained from Jackson Labs and housed 4 per cage under 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness, in light-tight chambers, for at least two weeks to entrain their circadian rhythms. Under these lighting conditions, denoted as LD, zeitgeber time 0 (ZT0) represents the time of lights-on in the colony. The corresponding time of lights-off is denoted as ZT 12. Room temperature and humidity were regulated at 22°C and 39%, respectively. Feed and water was available ad libitum. Animal use was in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice exhibited at least 3 consecutive regular estrous cycles, as determined by vaginal swabbing, prior to their inclusion in the experiment (Karman and Tischkau, 2006). Mice without regular estrous cycles were excluded from the experiment. Animals were orally dosed with 1 µg/kg of body weight (BW) of TCDD or vehicle (corn oil) during their lights-on period and released into constant darkness (DD) 6 days after treatment (Mukai et al., 2008). Under DD conditions, animals express their endogenous circadian rhythm, denoted as circadian time (CT), where CT is arbitrarily set as the onset of light in the previous light dark cycle. Thus CT0 and ZT0 are the same time of day. After 48 h in constant darkness, animals were killed by decapitation every 4 h over a 24-h period (n=4 per group) starting at CT0. Ovaries were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for immunoblot, co-immunoprecipitation or mRNA analysis.

2.2 Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

Total ovarian RNA was extracted using TRI-reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Concentration, quality and purity of RNA samples were determined with the Nanodrop ND-1000 UV spectrophotometer, and by gel electrophoresis. RT reactions and PCR were performed as previously described (Karman and Tischkau, 2006). Intron-spanning primers for AhR, Per2 and BMAL1 were chosen using Primer Express 3 software and have been published previously (Mukai et al., 2008; Mukai and Tischkau, 2007). Transcript levels were determined using the relative standard curve method for calculations. Standard curves were derived from 3 sets of pooled RNA samples using a range of RNA concentrations between 2 µg and 62.5 ng. The standard curve equation for AhR was y=−1.4068x+42.221 (R2=0.9755, E=1.64, where E= the efficiency of doubling in each cycle); for Bmal1 was y=−1.22x+33.52 (R2=0.9975, E=1.76); and for Per2 was y=−1.0587x+35.958 (R2=0.9924, E=1.94). Relative amounts of AhR, Bmal1 and Per2 were determined according to the equation: relative amount=2([Ct-Intercept]/[slope]). Relative amount was converted to percent of the maximum amount for each experiment. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

2.3 Immunoblot

Ovarian tissues were homogenized in Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) on ice using cold glass beads and a bead beater. Protein was quantified using the Micro BCA protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as previously described (Karman and Tischkau, 2006). Blots were blocked in non-fat dry milk, incubated with primary antibody solution overnight at 4°C (PER2 affinity purified 5 µg/ml; ADI, San Antonio, TX; BMAL1 affinity purified 5 µg/ml; ABR, Golden, CO; AhR 1µg/ml, Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA). After exposure to secondary antibody, membranes were washed and developed using chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Pierce). Densitometry using the digital imaging software Scion Image for Windows 4.0.3 (Scion Corporation) provided quantitative analysis of data. The relative density was normalized against alpha tubulin. Data were plotted as fold change from the lowest point.

2.4 Co-immunoprecipitation

Tissue lysates were prepared from whole ovaries as described above, centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min and then quantitated with the BCA kit. Soluble proteins (500 µg) were incubated on a rotating platform with 2 µg of goat anti-AhR antibody (Santa Cruz) or rabbit anti-BMAL1 antibody (ABR) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with immobilized protein A/G gel slurry (Pierce) at room temperature for 2 h with gentle mixing. Beads were collected by brief centrifugation and washed five times with 0.5 ml of immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (25 mM Tris and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2). The complex-bound gel was washed with 0.5 ml of water and centrifuged for 3 min at 2500 × g, the supernatant was discarded, laemmli buffer was added and samples boiled for 5 min at 95°C. Proteins were separated by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) for 1 h. The membrane, containing protein pulled down by either anti-AhR or anti-BMAL1 antibody, was incubated with the alternate antibody, washed with TBST and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature.

2.5 Immunohistochemistry

Despite repeated attempts, the AhR antibody failed to show specific staining in the mouse ovary. Therefore, adult female Sprague-Dawley rats were used for these experiments. Housing was exactly as described for the mice. Rat ovaries were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 h at room temperature. After paraffin embedding, 4 µm sections were cut. After deparaffinization, antigen retrieval, and blocking in normal goat serum, slides were incubated overnight in primary antibody, AhR (Biomol) or BMAL1 (ABR). Primary antibodies were used at 10 µg/ml. Sections were washed and incubated with an HRP-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The peroxidase antibody complex was visualized using aminoethyl carbazole substrate (Zymed, San Francisco, CA). Control experiments included omission of the primary antibody and preabsorption with the peptide specific to the primary antibody. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Results from qPCR and immunoblot studies were subjected to statistical analysis using two-way analysis of variance. Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was applied when the analysis of variance indicated that statistically significant differences were present. A p value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 TCDD alters circadian expression of circadian clock genes in the mouse ovary

Six days following administration of a single, low dose (1 µg/kg) of TCDD (or corn oil vehicle for the control group) by gavage, mice were placed into DD for 48 h to allow expression of their endogenous circadian rhythm. Starting at 48 h after placement into DD, mice were sacrificed and ovaries were collected every 4 h for 24 h. The status of the circadian clock was determined by examining 24-h profiles of transcripts and proteins for the canonical clock genes Bmal1 and Per2. Control animals displayed a robust circadian variation in the levels of transcripts and proteins for both Bmal1 and Per2 (Fig. 1). Bmal1 transcripts were maximal at CT0 with a 7.23±0.14 fold oscillation between peak and trough; the oscillation for the BMAL1 protein was 4.24±0.37 fold, with a peak also occurring at CT0 (Fig. 1a–b). The Per2 transcript rhythm in control animals was out-of-phase with the Bmal1 rhythm, as expected. Per2 transcripts displayed a 4.79±0.21 fold change, with a peak at CT12; the Per2 protein oscillation was comparable to the transcript oscillation at 4.04±0.31 fold with peak levels observed with the typical 4 h delay, at CT16 (Fig. 1c–d).

Fig. 1. Effects of TCDD on circadian rhythms of Bmal1 and Per2 in the mouse ovary.

A) Bmal1 transcript rhythms are dampened after TCDD treatment (n=3–6 per timepoint). Bmal1 transcripts are significantly lower at CT0 and CT20 in TCDD-treated mice (p<0.01; ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis). B) The BMAL1 protein rhythm was altered by TCDD (n=3–6 per timepoint). Blots are representative of 3–6 independent samples per timepoint. BMAL1 is decreased at CT0 and increased at CT16 compared to control. (p<0.01; ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis). C) Time of peak expression of Per2 mRNA is altered in TCDD treated mouse ovaries. Per2 transcripts are significantly higher at CT12 and CT16 in TCDD-treated mice (p<0.01; ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis). D) The PER2 protein rhythm was altered by TCDD (n=3–6 per timepoint). Blots are representative of 3–6 independent samples per timepoint. PER2 is decreased at CT0 and increased at CT12 compared to control. (p<0.01; ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis).

Bmal1 and Per2 levels were altered after TCDD treatment. Peak levels of Bmal1 transcripts were significantly suppressed in TCDD-treated mice; the amplitude of the change was reduced from 7.23±0.14 fold to 2.40±0.11 fold (Fig 1a). Peak transcript levels were observed at CT4, although there was no significant difference between CT4 and CT0. The amplitude of the BMAL1 protein oscillation was not altered by TCDD treatment, although the phase of the rhythm appeared to be shifted by 4 h. After TCDD treatment the time-of-peak Per2 transcript levels shifted from CT12 to CT16, and the amplitude of the oscillation was not significantly changed (Fig. 1c). Per2 protein oscillations were similarly altered such that the time-of-peak was delayed to occur 4–8 h later.

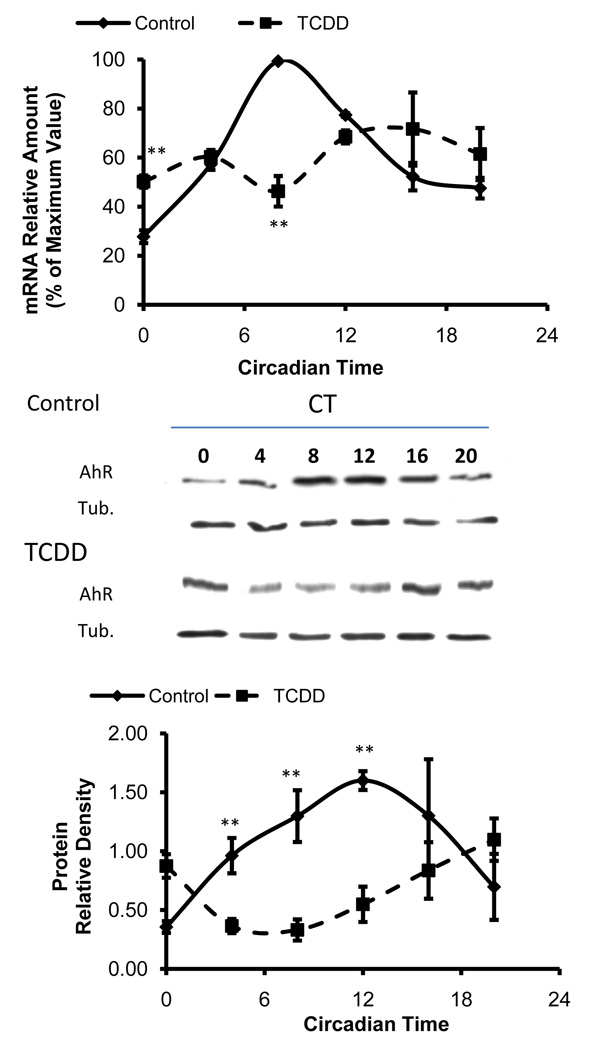

3.2 TCDD alters circadian rhythms of AhR in the mouse ovary

AhR transcript and protein were expressed with a circadian rhythm in the mouse ovary under control conditions (Fig. 2). Transcript levels for AhR were maximal at CT8 and minimal at CT0, with a 3.70±0.22 fold difference between peak and trough values. The amplitude of the AhR protein oscillation was 3.98±0.38 fold, with a peak at CT12 and minimal expression levels at CT0. Circadian expression of AhR transcript and protein was altered significantly by TCDD treatment. There was no oscillation in AhR transcript levels after TCDD treatment (Fig. 2a). The oscillation in AhR protein was retained upon TCDD treatment with a 3.15±0.45 fold amplitude, although protein expression patterns were dramatically altered (Fig. 2b). Peak protein levels shifted from CT12 in controls to CT20 in TCDD-treated mice.

Fig. 2. Effects of TCDD on circadian rhythms of AhR in the mouse ovary.

A) AhR transcript rhythms are dampened after TCDD treatment (n=3–6 per timepoint). AhR transcripts are significantly lower at CT8 and higher at CT0 in TCDD-treated mice (p<0.01; ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis). B) The AhR protein rhythm was altered by TCDD (n=3–6 per timepoint). Blots are representative of 3–6 independent samples per timepoint. AhR is decreased at CT0 and increased at CT4, 8 and 12 compared to control. (p<0.01; ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis).

3.3 AhR interactions with BMAL1 are enhanced by TCDD treatment

Previously, we demonstrated that AhR could form a heterodimer with BMAL1 to alter Per1 expression in the liver. To determine whether AhR and BMAL1 interact in the ovary, we first examined the expression patterns of both proteins in the rat ovary. Immunohistochemistry demonstrates that AhR and BMAL1 expression occurs in a similar pattern in the ovary (Fig. 3). Both BMAL1 (left column) and AhR (right column) are present in developing follicles at all stages of development, in the ovarian stroma, and in luteal cells.

Fig. 3. Immunohistochemistry of AhR and BMAL1 in the rat ovary.

Staining of consecutive sections shows similarity in localization of AhR and BMAl1 in structures of the rat ovary.

Co-immunoprecipitation demonstrates that AhR can interact with BMAL1 in the ovary and that this interaction is enhanced after TCDD treatment (Fig. 4). After pull-down with the AhR antibody, ovarian extracts were run on a gel and probed for BMAL1 (Fig. 4a). In control samples, the band for BMAL1 was stronger at CT4 than at CT20. The BMAL1 band was enhanced in CT4 samples obtained from TCDD treated mice. AhR was also found in samples after a pull-down with the BMAL1 antibody (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, specificity of the interaction was demonstrated by showing that neither the nuclear BMAL1 protein nor AhR protein interacts with the primarily cytoplasmic calbindin protein and there were no bands in the NRS controls.

Fig. 4. Interactions of AhR and BMAL1 are enhanced by TCDD treatment.

A) BMAL1 immunoreactivity in protein lysates immunoprecipitated with an AhR antibody is increased at CT4 compared to CT20 in untreated controls and increased after TCDD treatment at CT4. BMAL1 was not co-immunoprecipitated with a calbindin (Calb) antibody or when normal rabbit serum was used for precipitation (NRS). B) AhR immunoreactivity in protein lysates immunoprecipitated with a BMAL1 antibody is increased at CT4 in TCDD-treated mice. Blots is representative of 3 experiments.

4. Discussion

The results presented in this manuscript clearly demonstrate that the circadian expression pattern of AhR is altered in the ovaries of adult female mice after exposure to a low dose of TCDD. Circadian patterns of expression of the canonical clock genes, Bmal1 and Per2, are also altered after TCDD exposure. TCDD enhanced interactions between AhR and BMAL1, suggesting a potential mechanism for altered circadian rhythms. Thus, these data invoke a novel mechanism for dioxin action downstream of AhR activation and highlight the importance of crosstalk between AhR signaling and the molecular circadian clockworks in ovarian function.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine an alteration in expression of circadian rhythms in the ovary after TCDD treatment. Circadian expression patterns of AhR mRNA and protein, as well as the canonical clock genes Bmal1 and Per2, were observed in the mouse ovary. It is not surprising that the clock genes were expressed with circadian periodicity in the mouse ovary, as previous studies indicated that these genes displayed diurnal rhythmicity in the rat ovary (Fahrenkrug et al., 2006; Karman and Tischkau, 2006; Nakamura et al., 2010). Similarly, the circadian expression of AhR is in relative agreement with previous studies demonstrating that AhR protein oscillates in the liver, lungs, and thymus of rats (Richardson et al., 1998). AhR transcripts are also clearly rhythmic in the in rat liver, although the time of peak relative to the light schedule (14L:10D) was not reported (Huang et al., 2002). In a previous study from our laboratory, AhR transcripts were rhythmic in both suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and liver under LD and DD (Mukai et al., 2008). Peak mRNA expression of AhR in both SCN and liver under LD occurred at ZT12 and ZT8, respectively. Collectively, the available data suggest that AhR expression in under the control of the circadian clock.

The data presented in this manuscript clearly indicate that a single, low dose of TCDD is sufficient to alter expression of the canonical clock genes, BMAL1 and Per2, in the mouse ovary. Other literature on dysregulation of circadian rhythms after AhR activation is limited. Doses of TCDD 1000 times higher than used in the current study cause altered behavioral rhythmicity in mice (Frame et al., 2004; Miller et al., 1999), which is associated with a concomitant divergence in the expression pattern of PER1 protein in the SCN of these mice. The SCN clock has a diminished ability to respond to nocturnal light after TCDD exposure, an event dependent on the clock gene Per1 (Mukai et al., 2008; Tischkau et al., 2003). AhR activation subsequent to TCDD administration significantly altered the phase, period and amplitude of circadian rhythms in the numbers of antigenically and functionally defined hematopoietic progenitor cell classes in bone marrow. TCDD-induced changes were associated with dampening of the rhythms of the clock genes Per1 and Per2, which may imply a direct crosstalk between AhR signaling and the core circadian clock (Garrett and Gasiewicz, 2006). Previous studies in our own laboratory also demonstrated phase alteration and dampening of Per1 and BMAL1 rhythms in the mouse liver after a single low dose of TCDD (Mukai et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010). Consistent with those results, the Bmal1 mRNA rhythm was dampened in this study; however, only the phase of the Per2 rhythm was changed. The collective data indicate that TCDD alters circadian rhythms by acting directly on the primary clock in the SCN and by acting on clocks located in peripheral tissues.

TCDD also affected the circadian expression of AhR in the mouse ovary. Although AhR mRNA was clearly rhythmic in the control animals with peak levels at CT8, the rhythm was abolished after TCDD treatment. TCDD did not ablate the rhythm in AhR protein, which peaked at CT12 in control animals. Rather, the peak was shifted 12 h out of phase after TCDD treatment. The reason for this discrepancy between effects on AhR mRNA and protein is not clear at this time. However, the data do suggest that posttranslational modifications and/or alteration in protein degradation may also be involved in circadian regulation of the AhR protein. The altered rhythmicity in AhR may be a consequence of altered expression of the circadian genes. Silencing of Per2 significantly alters AhR and ARNT expression in response to TCDD treatment (Qu et al., 2009). AhR/ARNT and the core circadian clock elements are PAS proteins capable of promiscuous interactions. Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that clock disruption might be a common feature underlying alteration in biological processes consequent to dioxin exposure.

Structural similarity between AhR and the canonical circadian clock elements, particularly BMAL1 (Takahata et al., 2000), suggests the possibility that AhR and/or ARNT may be in involved in the regulation of circadian rhythmicity. Protein-protein interactions regulated by PAS domain-containing proteins are central to both circadian clock regulation and to AhR signaling (McIntosh et al., 2010). PAS domain proteins, however, are notoriously promiscuous. Heterodimers can form between many alternative family members, providing ample opportunity for diverse functionality and crosstalk. Not surprisingly given the multiplicity of PAS domain interactions, it seems that the two pathways are intertwined in a relatively complex manner. Activation of AhR leads to alteration of the clockworks (Garrett and Gasiewicz, 2006; Mukai et al., 2008; Mukai and Tischkau, 2007; Xu et al., 2010), and reciprocally, the clock modulates the activity of AhR (Qu et al., 2007, , 2009; Qu et al., 2010). In the present study, TCDD administration increased physical interactions between AhR and Bmal1, suggesting that these two PAS domain proteins can for a functional heterodimer in the ovary. Although we did not examine functional consequences of AhR/BMAL1 complexes in the ovary, our previous data suggest that this heterodimer can repress Per1 (Xu et al., 2010). Inhibition of Per1 would dampen the robustness of core clock and slow its progression. Per1 rhythms in liver are attenuated and phase delayed after TCDD exposure (Xu et al., 2010), which is compelling evidence that AhR slows and weakens circadian rhythmicity.

Conversely, disruption of the clockworks, specifically in the presence of aberrant Per1 expression, precipitates changes in AhR signaling. Production of the AhR target genes are significantly enhanced after Per1 knockdown using siRNA, or in animals bearing mutated Per1 genes (Qu et al., 2007, , 2009; Qu et al., 2010). Although the molecular events underlying the heightened AhR activity remains unknown, it is tempting to speculate that PER1 may physically interact with the AhR/ARNT heterodimer to function as a transcriptional repressor, similar to the effects of PER1 on CLOCK/BMAL1. The aggregate data paint a complex picture of reciprocal interactions between AhR signaling, which is enhanced by TCDD treatment as in the current study, and the molecular clockworks.

Whether the effects of TCDD are mediated within the ovary itself or through interactions of TCDD at other sites in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis remains an open question. TCDD is known to alter hypothalamic and pituitary production of gonadotropic hormones, leading to inhibition of ovulation (Li et al., 1995a, 1995b). Ovarian clock gene expression is also influenced by the gonadotropins (Karman and Tischkau, 2006; Nakamura et al., 2010). However, interactions of AhR and Bmal1 specifically within the ovary were enhanced by TCDD treatment, suggesting direct action of TCDD on the ovary. Furthermore, the consequences of TCDD-induced alteration in circadian rhythms in the ovary remain unknown. However, both the circadian clock and AhR regulate cell cycle progression, and that AhR is important for follicle development in the ovary (Borgs et al., 2009; Hernandez-Ochoa et al., 2009). Thus, disruption of circadian clock function after TCDD may alter follicular development. Future studies will investigate how interactions of AhR and clock genes affect ovarian function.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of B. Karman and M. Mukai. Funding was provided through NIH grants ES012948 and ES 017774 to SAT.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aylward LL, Brunet RC, Carrier G, Hays SM, Cushing CA, Needham LL, Patterson DG, Jr, Gerthoux PM, Brambilla P, Mocarelli P. Concentration-dependent TCDD elimination kinetics in humans: toxicokinetic modeling for moderately to highly exposed adults from Seveso, Italy, and Vienna, Austria, and impact on dose estimates for the NIOSH cohort. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15:51–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beischlag TV, Luis Morales J, Hollingshead BD, Perdew GH. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2008;18:207–250. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v18.i3.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum LS. The mechanism of dioxin toxicity: relationship to risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102 Suppl 9:157–167. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s9157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgs L, Beukelaers P, Vandenbosch R, Belachew S, Nguyen L, Malgrange B. Cell "circadian" cycle: new role for mammalian core clock genes. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:832–837. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.6.7869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison MS, Fisher JM, Whitlock JP., Jr Protein-DNA interactions at recognition sites for the dioxin-Ah receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16478–16482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enan E, Matsumura F. Evidence for a second pathway in the action mechanism of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Significance of Ah-receptor mediated activation of protein kinase under cell-free conditions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49:249–261. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(94)00430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrug J, Georg B, Hannibal J, Hindersson P, Gras S. Diurnal rhythmicity of the clock genes Per1 and Per2 in the rat ovary. Endocrinol. 2006;147:3769–3776. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame L, Li W, Miller J, Dickerson R. A proposed role for the arylhydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in non-photic feedback to the master circadian clock. Toxicologist. 2004;78:954. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett RW, Gasiewicz TA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin alters the circadian rhythms, quiescence, and expression of clock genes in murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:2076–2083. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He PJ, Hirata M, Yamauchi N, Hashimoto S, Hattori MA. The disruption of circadian clockwork in differentiating cells from rat reproductive tissues as identified by in vitro real-time monitoring system. J Endocrinol. 2007a;193:413–420. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He PJ, Hirata M, Yamauchi N, Hashimoto S, Hattori MA. Gonadotropic regulation of circadian clockwork in rat granulosa cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007b;302:111–118. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Ochoa I, Karman BN, Flaws JA. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the female reproductive system. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:547–559. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogenesch JB, Chan WK, Jackiw VH, Brown RC, Gu Y-Z, Pray-Grant M, Perdew GH, Bradfield CA. Characterization of a Subset of the Basic-Helix-Loop-Helix-PAS Superfamily That Interacts with Components of the Dioxin Signaling Pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8581–8593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogenesch JB, Gu YZ, Jain S, Bradfield CA. The basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS orphan MOP3 forms transcriptionally active complexes with circadian and hypoxia factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5474–5479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Ceccatelli S, Rannug A. A study on diurnal mRNA expression of CYP1A1, AHR, ARNT and PER2 in rat pituitary and liver. Env Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;11:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s1382-6689(01)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karman BN, Tischkau SA. Circadian clock gene expression in the ovary: Effects of luteinizing hormone. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:624–632. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.050732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner HE, Vulimiri SV, Hatten WB, Reed MJ, Nebert DW, Jefcoate CR, DiGiovanni J. Role of cytochrome p4501 family members in the metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mouse epidermis. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:1667–1674. doi: 10.1021/tx049919c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni PS, Crespo JG, Afonso CA. Dioxins sources and current remediation technologies--a review. Environ Int. 2008;34:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Johnson DC, Rozman KK. Effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) on estrous cyclicity and ovulation in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Lett. 1995a;78:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03252-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Johnson DC, Rozman KK. Reproductive effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in female rats: ovulation, hormonal regulation, and possible mechanism(s) Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995b;133:321–327. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh BE, Hogenesch JB, Bradfield CA. Mammalian Per-Arnt-Sim proteins in environmental adaptation. Ann Rev Physiol. 2010;72:625–645. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Settachan D, Frame L, Dickerson R. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodobenzo-p-dioxin phase advance the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) circadian rhythm by alterinf expression of clock proteins. Org Comp. 1999;42:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Borgeest C, Greenfeld C, Tomic D, Flaws J. In utero effects of chemicals on reproductive tissues in females. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;198:111–131. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai M, Lin TM, Peterson RE, Cooke PS, Tischkau SA. Behavioral rhythmicity of mice lacking AhR and attenuation of light-induced phase shift by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. J Biol Rhythm. 2008;23:200–210. doi: 10.1177/0748730408316022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai M, Tischkau SA. Effects of tryptophan photoproducts in the circadian timing system: searching for a physiological role for aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:172–181. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura TJ, Sellix MT, Kudo T, Nakao N, Yoshimura T, Ebihara S, Colwell CS, Block GD. Influence of the estrous cycle on clock gene expression in reproductive tissues: effects of fluctuating ovarian steroid hormone levels. Steroids. 2010;75:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Dalton TP, Okey AB, Gonzalez FJ. Role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated induction of the CYP1 enzymes in environmental toxicity and cancer. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23847–23850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Puga A, Vasiliou V. Role of the Ah receptor and the dioxin-inducible [Ah] gene battery in toxicity, cancer, and signal transduction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;685:624–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb35928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroff B, Roby K, Gao X, Son D, Williams S, Johnson D, Rozman K, Terranova P. A review of mechanisms controlling ovulation with implications for the anovulatory effects of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins in rodents. Toxicol. 2001;158:91–107. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrulis JR, Perdew GH. The role of chaperone proteins in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor core complex. Chem Biol Interact. 2002;141:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocar P, Fischer B, Klonisch T, Hombach-Klonisch S. Molecular interactions of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its biological and toxicological relevance for reproduction. Reprod. 2005;129:379–389. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjanvirta R, Unkila M, Tuomisto J. TCDD-induced hypophagia is not explained by nausea. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;47:273–282. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst MR, Fan CM, Tessier-Lavigne M, Hankinson O. Two murine homologs of the Drosophila single-minded protein that interact with the mouse aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4451–4457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puga A, Hoffer A, Zhou S, Bohm JM, Leikauf GD, Shertzer HG. Sustained increase in intracellular free calcium and activation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in mouse hepatoma cells treated with dioxin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00417-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puga A, Ma C, Marlowe JL. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor cross-talks with multiple signal transduction pathways. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Metz RP, Porter WW, Cassone VM, Earnest DJ. Disruption of clock gene expression alters responses of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway in the mouse mammary gland. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1349–1358. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Metz RP, Porter WW, Cassone VM, Earnest DJ. Disruption of period gene expression alters the inductive effects of dioxin on the AhR signaling pathway in the mouse liver. Toxicol ApplPharmacol. 2009;234:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Metz RP, Porter WW, Neuendorff N, Earnest BJ, Earnest DJ. The clock genes period 1 and period 2 mediate diurnal rhythms in dioxin-induced Cyp1A1 expression in the mouse mammary gland and liver. Toxicol Lett. 2010;196:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak CK, Boehle KL, Muglia LJ. Impaired steroidogenesis and implantation failure in Bmal1−/− mice. Endocrinol. 2009;150:1879–1885. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson V, Santostefano M, Birnbaum LS. Daily cycle of bHLH-PAS proteins, Ah receptor and Arnt, in multiple tissues of female Sprague-Dawley rats. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1998;252:225–231. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata S, Ozaki T, Mimura J, Kikuchi Y, Sogawa K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Transactivation mechanisms of mouse clock transcription factors, mClock and mArnt3. Genes to Cells. 2000;5:739–747. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkau S, Howell R, Hickok J, Krager SL, Bahr JM. The luteinizing hormone surge regulates circadian clock gene expression in the chicken ovary. Chronobiol Int. 2011 doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.530363. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkau SA, Mitchell JW, Tyan SH, Buchanan GF, Gillette MU. Ca2+/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-dependent activation of Per1 is required for light-induced signaling in the suprachiasmatic nucleus circadian clock. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:718–723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis CC, Hattemer-Frey HA. Human exposure to dioxin. Sci Total Environ. 1991;104:97–127. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90010-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu CX, Krager SL, Liao DF, Tischkau SA. Disruption of CLOCK-BMAL1 transcriptional activity is responsible for aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated regulation of Period1 gene. Toxicol Sci. 2010;115:98–108. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Ikeda M, Abe H, Honma S, Ebisawa T, Yamauchi T, Honma K, Nomura M. Characterization of three splice variants and genomic organization of the mouse SBMAL1 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1999;260:760–767. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]