Abstract

Low frequency temporal information present in speech is critical for normal perception, however the neural mechanism underlying the differentiation of slow rates in acoustic signals is not known. Data from the rat trigeminal system suggest that the paralemniscal pathway may be specifically tuned to code low-frequency temporal information. We tested whether this phenomenon occurs in the auditory system by measuring the representation of temporal rate in lemniscal and paralemniscal auditory thalamus and cortex in guinea pig. Similar to the trigeminal system, responses measured in auditory thalamus indicate that slow rates are differentially represented in a paralemniscal pathway. In cortex, both lemniscal and paralemniscal neurons indicated sensitivity to slow rates. We speculate that a paralemniscal pathway in the auditory system may be specifically tuned to code low frequency temporal information present in acoustic signals. These data suggest that somatosensory and auditory modalities have parallel sub-cortical pathways that separately process slow rates and the spatial representation of the sensory periphery.

Keywords: auditory thalamus, auditory cortex, guinea pig, paralemniscal auditory pathway, non-primary auditory pathway, temporal coding

1. Introduction

A prominent acoustical characteristic of animal communication calls, as well as human speech (Rosen, 1992), is low-frequency temporal information. For example, acoustical analysis of the guinea pig chutter and purr calls shows peaks in their temporal envelopes at approximately 5 and 10 Hz (Huetz, et al., 2009; Suta, et al., 2003).

In the auditory system, it has been suggested that temporal rate information is represented with a two-stage mechanism in auditory thalamus (Bartlett, et al., 2007) and cortex (Lu, et al., 2001). This model proposes that two populations of neurons in auditory thalamus and cortex facilitate the representation of a wide range of temporal features in acoustical signals in a complementary fashion. One population of neurons, referred to as the “synchronized” population, produce stimulus-synchronized discharges at long inter-stimulus intervals (i.e., low-frequency stimuli < 40 Hz) and little activity at shorter intervals. Another population of neurons, referred to as the “non-synchronized” population, do not exhibit stimulus-synchronized activity; rather, they represent acoustical stimuli with brief inter-stimulus intervals (higher frequency stimuli > 50 Hz) with monotonically changing discharge rate (Wang, et al., 2008). Results from the rat trigeminal system demonstrate that slow rates (between 2–8 Hz) are differentially coded by lemniscal and paralemniscal pathways (Ahissar, et al., 2000). Lemniscal neurons in both thalamus and cortex code stimulation frequency with constant latencies while paralemniscal neurons code stimulation frequency as systematic changes in latency. Based on its unique sensitivity for slow rates, it is suggested that the paralemniscal pathway is “optimally tuned for temporal processing of vibrissal information around the whisking frequency range (8 Hz)” (Ahissar, et al., 2000).

An hypothesis based on the somatosensory results is that a paralemniscal pathway in the auditory system may be tuned to code slow rates in acoustic signals. A parallel pathway system has been proposed by Rauschecker et al (Rauschecker, et al., 1997) and additionally it has been suggested that parallel pathways originate in subcortical structures (He, et al., 1998; Kosaki, et al., 1997). The results of temporal integration in the dorsal cortex of the cat further suggest that the paralemniscal pathway might be involved in temporal information processing (He, et al., 1997). Surprisingly, there has been no systematic investigation of paralemniscal representation of acoustic rate in auditory thalamus and whether it differs from the lemniscal representation. To investigate temporal response properties of lemniscal and paralemniscal regions of the thalamocortical auditory system, we measured local field potentials (LFPs) from lemniscal and paralemniscal neurons in guinea pig thalamus and cortex in response to click trains with rates between 2–8 Hz.

2. Materials and Methods

The research protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University.

2.1 Animal preparation

The experimental materials and procedures were similar to those reported previously (Cunningham, et al., 2002; McGee, et al., 1996). Eighteen pigmented guinea pigs of either sex, weighing between 400–600 g, were used as subjects. Animals were initially anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg). Smaller supplemental doses (25 mg/kg ketamine; 4 mg/kg xylazine) were administered hourly or as needed throughout the rest of the experiment. Following the induction of anesthesia, the animal was mounted in a stereotaxic device, located in a sound-treated booth (IAC), for the duration of the experiment. Body temperature was maintained at 37.5° C by using a thermistor-controlled heating pad on the guinea pig’s abdomen (Harvard). Normal hearing sensitivity was confirmed by auditory brainstem response. The auditory brainstem response was elicited by a click stimulus at 70 and 40 dB HL (referenced to normal guinea pig click thresholds) from a recording site located at the posterior vertex/midline of the scalp using an EMG needle electrode. A rostro-caudal incision was made along the scalp surface and the tissue was retracted to expose the skull. Holes were drilled in the skull under an operating microscope. The dura was removed with a cautery to prevent damage to the recording electrode, and the cortical surface was coated with mineral oil.

2.2 Anatomical structures

The lemniscal and paralemniscal auditory nuclei investigated in the present study were selected because they have the same reciprocal and parallel connectivity patterns as the lemniscal and paralemniscal pathways in the rat trigeminal system (somatosensory: (Diamond, et al., 1992; Woolsey, 1997); auditory: (Redies, et al., 1989b)). The lemniscal pathway described here consists of the ventral nucleus of the medial geniculate body of thalamus (MGv) and primary auditory cortex. MGv is tonotopically organized, shows a preference for tonal stimuli and exhibits short-latency responses (He, 2002; Redies, et al., 1991). Primary auditory cortex in guinea pig consists of two areas, A1 and the dorsocaudal field (DC), which are characterized by tonotopic organization, sharp frequency tuning, a preference for tonal stimuli and short response latencies (Redies, et al., 1989a; Wallace, et al., 2000). Lemniscal cortex receives its afferent thalamic input from MGv (Redies, et al., 1989b).

The paralemniscal nucleus of thalamus described here is the shell nucleus of the medial geniculate body (MGs) (He, 2002; Redies, et al., 1989b). The shell nucleus is a band of neurons that surround the MGv dorsally, laterally and ventrally. Neurons of the MGs are generally characterized by broad frequency tuning and long-latency responses (He, 2002; Redies, et al., 1991). This nucleus projects to the ventral caudal belt of auditory cortex (VCB), the paralemniscal cortical area described in the present work. Neurons of VCB show broad frequency tuning, are more responsive to noise compared to pure tones, and have long-latency responses (Wallace, et al., 2000). Based on these particular anatomical connections, it is postulated that these auditory thalamocortical connections represent parallel pathways in the ascending auditory system.

We performed histology on MGv and MGs using hematoxylin and eosin staining and only subtle differences were evident between MGv and MGs with respect to the density of cell bodies. This corroborates previous anatomical investigations of guinea pig MGB using Nissl-staining indicating an indistinct cytoarchitectonic division between these nuclei; it was proposed that the cell population of these nuclei is intermingled (Redies, et al., 1989b). During data collection, we relied on the relative anatomical locations of these nuclei, as well as the substantial differences between their response properties to various probe stimuli, as means to distinguish these two nuclei.

2.3 Acoustic stimuli

Acoustic stimuli were generated digitally and presented in Matlab (Mathworks). Acoustic stimuli were delivered to the contralateral ear using Etymotic insert earphones (ER2) through the hollow earbars of the stereotaxic device. The sound pressure level (SPL, expressed in dB re 20 mPa) was calibrated over a frequency range of 0.02–20 kHz using a condenser microphone (Brüel and Kjaer). Three-second-long click train stimuli were delivered at a level of 75 dB SPL (peak intensity). Click trains of 2, 5 and 8 Hz were randomly presented with an inter-stimulus interval of 1 s. At all electrode penetrations, each of the three click rates was presented 100 times. Clicks consisted of 100 μsec rectangular pulses. Clicks with alternating polarities were presented to remove any possibility of a stimulus artifact within the response. The delivery system outputted the signal through a 16-bit converter at a sampling rate of 16 kHz. That system triggered the PC-based collection computer. Third-octave tone-pips were used to map auditory cortex. Mapping of auditory cortex was essential to properly locating the paralemniscal cortical nucleus. Tones were 100 msec in duration with a rise-fall time of 10 msec.

2.4 Neurophysiological recording

Both thalamus and cortex were accessed with a vertical approach using tungsten microelectrodes (Micro Probe) with impedance between 1–2 MΩ at 1 kHz. An electrode was advanced perpendicular to the surface of cortex using a remote-controlled micromanipulator (Märzhäuser-Wetzlar). For both MG and cortical recordings, the dorsal/ventral reference of the electrode was determined at a point slightly above cortex at the first penetration, and this coordinate was kept for the remainder of the experiment.

Typically, recordings of MG and cortex were performed on different animals and recording sessions. For recording MGv, rostral/caudal and medial/lateral references were set at the interaural line and bregma, respectively. Locations were approximately 4.8 mm rostral to the interaural line, 4.0 mm left or right of bregma and 7.2 mm ventral to the surface of the brain. During penetration, auditory stimuli were delivered (clicks at 3.5 Hz), and visual inspection, using a monitoring oscilloscope, of the response size and waveform morphology was considered. If the response was small in amplitude and broad in shape, electrode penetration was continued. This process was repeated until the morphology of the waveform conformed to the large amplitude, sharp onset response commonly observed in recordings obtained from the ventral division of the MG. Previous use of this technique has shown a 100% hit rate for the ventral division of the medial geniculate using the stereotaxic and physiological criteria described above (Cunningham, et al., 2002; King, et al., 1999). For recording MGs, the same recording procedures described above were used, however the recording electrode was gradually moved laterally from MGv until neural responses to clicks increased in latency, a known characteristic of MGs (He, 2002; Redies, et al., 1991). Due to the relatively large volume measured with LFPs and the proximity of lemniscal and paralemniscal nuclei, on many occasions the responses to both nuclei were recorded at a single penetration. Responses from these nuclei were often separable in single trial observations, as monitored on our oscilloscope, and were always separable in the 100 trial averaged waveforms.

For recording lemniscal areas A1 and DC, both rostral/caudal and medial/lateral references were set at bregma. Locations were approximately 3 mm caudal to and 10 mm lateral of bregma. Recordings were made at depths of 500–900 μm, corresponding to cortical layers III and IV in guinea pig. Auditory cortex was mapped using third-octave tones to enable description of best frequency for lemniscal penetrations. To determine the location of paralemniscal area VCB, we used the frequency map of lemniscal regions A1 and DC to identify the ventral border of area DC which abuts area VCB. VCB was easily identified when the electrode had entered this cortical region: neural responses became significantly later, showed negligible and non-frequency-specific responses to pure-tones, and moderate-to-large responses to noise bursts (Wallace, et al., 2000).

LFPs were measured from 35 penetrations in lemniscal auditory thalamus (MGv) and 15 penetrations in paralemniscal auditory thalamus (MGs). LFPs were measured from 29 penetrations in lemniscal auditory cortex (fields A1 and DC) and 24 penetrations in paralemniscal auditory cortex (VCB). We have chosen to analyze LFPs here as a means to examine neural activity across a large population of neurons. We reasoned that if systematic latency shifts serve as an important mechanism for the processing of acoustic rate information, then these latency shifts should be evident in relatively gross measures of neural activity measured across large neuronal populations.

The electrode signal was amplified using Grass amplifiers with filters set between 1–20,000 Hz. The analog signal was digitized at 33.3 kHz by an A–D card (MCC) attached to a PC-based computer system. Responses were logged and stored using Matlab routines designed by our lab. Recorded brain responses were offline filtered between 10–100 Hz to isolate local field potentials (LFPs) (Eggermont, et al., 1995) and downsampled to 10 kHz using an algorithm that applies an anti-aliasing (lowpass) FIR filter during the downsampling process (Matlab, Mathworks, Inc). Following each experiment, the final thalamic recording location was marked with an electrolytic lesion (35 mA for 10 s) to enable correlation between electrophysiological recordings and histology.

2.5 Data Analysis

Grand average LFPs across 100 stimulus repetitions were calculated for all click rates and penetrations. To facilitate the examination of responses to early clicks in the stimulus trains, we first averaged the LFP waveforms in response to clicks two and three of the train for each click rate. The justification for analyzing responses to these early clicks in the train is that accurate coding of low frequency information in communication signals (i.e., guinea pig chutter and purr calls) likely requires an efficient neural mechanism that can rapidly track the temporal features of these communication calls. In addition, we analyzed “steady-state” LFPs, defined here as the average LFP measured during the final second of the click train at each rate. The reason for this analysis is that it enabled direct comparison to the results from the rat trigeminal system (Ahissar, et al., 2000).

The first major deflection in the LFP was identified automatically using software code in Matlab. Correct identification of all peaks was verified visually. Amplitudes and latencies at both LFP peak and half-peak were identified for statistical analysis. Since the goal of this paper is to investigate effects of click rate on LFP latency, we are only presenting peak amplitude statistics. Peak and half-peak latencies as well as peak amplitudes were statistically evaluated using a repeated-measures design which enabled a description of within-penetration changes in LFP latency and amplitude for increasing stimulus rate. When comparison of responses between nuclei is reported, these analyses were also conducted using a repeated-measures design, which compared differences between nuclei in within-penetration changes in LFP latency and amplitude.

3. Results

3.1 Thalamus: lemniscal and paralemniscal responses

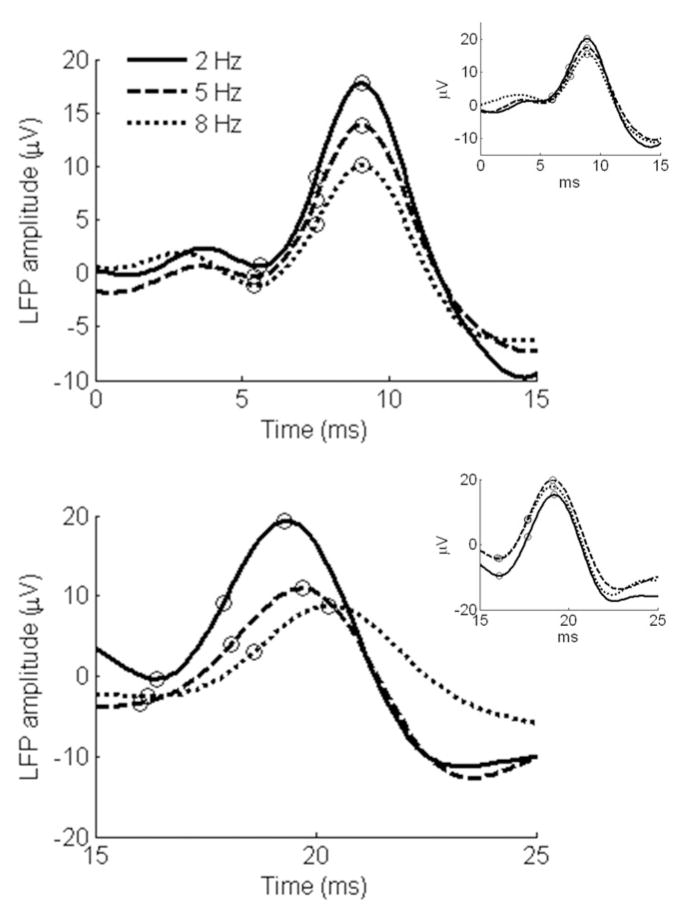

The averaged LFPs in response to the second and third clicks within a train are plotted at each of the three repetition rates as a function of time in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Thalamic LFPs to click trains.

(a) Representative lemniscal (MGv) and (b) paralemniscal thalamic (MGs) responses. Plots represent the average local field potential (LFP) in response to clicks 2 and 3 in a train. Figure 1 insets: plots represent LFPs in response to the first click in a train measured in MGv (Figure 1a inset) and MGs (Figure 1b inset). The circles on the plots indicate the peak, base and half-peak measures recorded for each LFP at each click rate.

In the lemniscal nucleus of the MG (Figure 1a), response characteristics were similar irrespective of click rate: response latency remained nearly constant while LFP amplitude decreased slightly with increasing stimulus rate, consistent with an adaptation process. Alternatively, in the paralemniscal nucleus of MG (Figure 1b), response latency systematically shifted later in time with increasing stimulus rate, with a similar amplitude decrement as that seen in the MGv. These particular response characteristics were seen across many penetrations measured in seven different experimental animals.

To quantify the effect of click rate on response latency and amplitude for lemniscal and paralemniscal thalamic nuclei for all recording penetrations (n=35 for MGv; n=15 for MGs), we identified the peaks in the LFP that corresponded to the second and third click in the train at each click rate and recorded their latency and amplitude values. Since paralemniscal auditory neurons typically respond later than lemniscal neurons (He, 2002; Redies, et al., 1991) (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics for lemniscal and paralemniscal thalamic responses), we wanted to ensure that statistical differences between lemniscal and paralemniscal LFPs were not due to proportionally similar latency increases. Therefore, we normalized response latencies measured at each penetration to the latency measured in the 2 Hz condition for that penetration.

Table 1.

| 2 Hz | 5 Hz | 3 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clicks 2 and 3 LFP | |||

| Peak Amplitude | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 30.526 (22.776) μV | 28.623 (22.833) μV | 26.692 (23.554) μV |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 11.621 (8.143) μV | 8.702 (6.002) μV | 6.035 (3.892) μV |

| Peak Latency | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 9.500 (1.175) ms | 9.523 (1.159) ms | 9.523 (1.173) ms |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 21.293 (3.751) ms | 21.713 (3.943) ms | 22.313 (3.640) ms |

| Half-Peak Latency | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 7.823 (1.032) ms | 7.831 (1.0197) ms | 7.806 (1.017) ms |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 18.887 (3.937) ms | 19.213 (3.842) ms | 19.527 (3.876) ms |

| Steady-State LFP | |||

| Peak Amplitude | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 31.339 (22.773) μV | 24.633 (17.023) μV | 22.314 (15.531) μV |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 11.1 (8.050) μV | 8.377 (4.594) μV | 6.646 (3.465) μV |

| Peak Latency | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 9.474 (1.132) ms | 9.549 (1.199) ms | 9.517(1.227) ms |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 22.193 (3.727) ms | 21.813 (3.731) ms | 22.34 (3.926) ms |

| Half-Peak Latency | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 7.843 (1.069) ms | 7.8571 (1.068) ms | 7.8286 (1.090) ms |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 18.893 (3.913) ms | 19.200 (3.960) ms | 19.560 (4.112) ms |

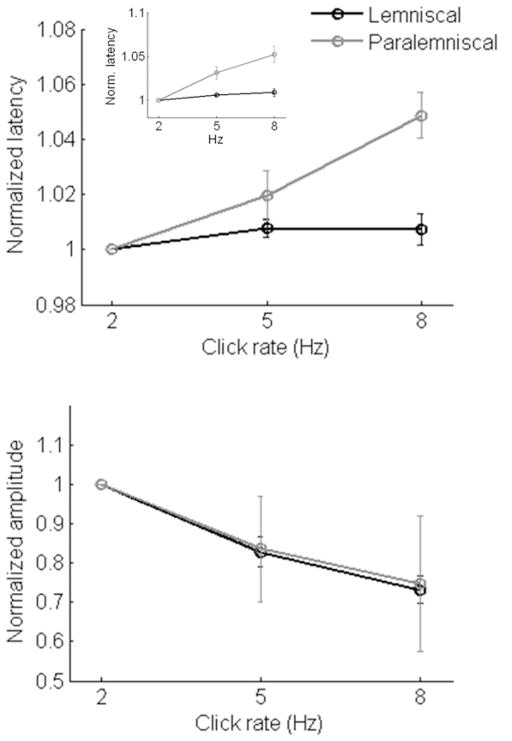

To test whether LFP latency characteristics distinguish lemniscal from paralemniscal thalamus, we performed a repeated measures ANOVA on normalized LFP peak latencies measured from MGv and MGs. A significant difference between lemniscal and paralemniscal response latency for increasing stimulus rates was confirmed by a significant effect of pathway in this analysis (F1,48 = 13.518, P=0.001; Figure 2a). Additional repeated measures ANOVA analyses revealed that there was no effect of click rate on LFP latencies measured from lemniscal thalamus (F2,68 = 1.89; P=0.159); however a significant effect of click rate on paralemniscal response latency was evidenced with increased latencies seen for increasing stimulus rates (F2,28 = 12.107, p=0.0001). Post hoc pairwise comparisons of paralemniscal latencies indicated significantly later responses for 5 Hz compared to 2 Hz click rates (t = 2.097, P=0.055) as well as 8 Hz compared to 5 Hz click rates (t = 2.405, P=0.03). Results from latency at half-peak were identical to those described for latency at peak (effect of pathway: F1,48 = 11.660; P=0.001; effect of click rate on lemniscal LFPs: F2,68 = .538, P=0.586; effect of click rate on paralemniscal LFPs: F2,28 = 24.752, P<0.0001). The same effects were also prevalent in peak latencies during the final second of the train (Figure 2a inset, effect of pathway: F1,48 = 19.722, P<0.0001; effect of click rate on lemniscal LFPs: F2,68 = 1.102, P=0.338; effect of click rate on paralemniscal LFPs: F2,28 = 24.752, P<0.0001). These results indicate that at the level of thalamus, a paralemniscal auditory nucleus systematically encodes temporal rate information in the form of a latency shift. This encoding is seen no later than the third click in a train and persists for up to 3 seconds.

Figure 2. Mean Thalamic LFPs.

Mean (± SE) local field potential (a) latency and (b) amplitude for lemniscal and paralemniscal thalamic responses. Figure 2a inset: mean “steady-state” thalamic LFP latencies.

To determine whether the effect of click rate on LFP amplitude distinguishes lemniscal from paralemniscal thalamus, the same statistical analyses were performed on peak amplitudes values (Figure 2b). All amplitude values from a given penetration were normalized with respect to amplitudes measured in the 2 Hz condition. There was no statistical difference between lemniscal and paralemniscal thalamus with respect to LFP amplitude changes for increasing stimulus rate (LFP amplitude pathway effect: F1,48 = 0.005, p = 0.945). Consistent with an adaptation process, increases in stimulus rate resulted in significant decreases in LFP amplitude in lemniscal thalamus (MGv: F2,68 = 30.076, P<0.0001). There was a trend for the same effect in paralemniscal thalamic nucleus (MGs: F2,28 = 1.931; P=0.160). The failure to reach statistical significance in paralemniscal thalamus was due to responses measured from a single penetration which showed a preference (i.e., larger LFP amplitudes) for rates greater than 2 Hz. When this outlying data point was removed from this analysis, an effect of stimulus rate on normalized LFP amplitude (i.e., adaptation) was evident (MGs: F2, 26 = 5.852; P=0.001). These data indicate similarity between lemniscal and paralemniscal LFP amplitudes in response to different click rates.

3.2 Cortex: lemniscal and paralemniscal responses

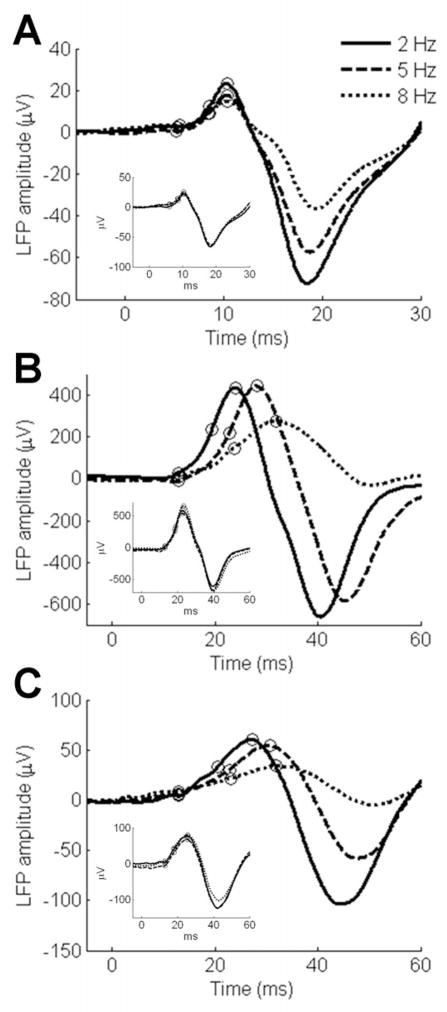

To determine if lemniscal and paralemniscal nuclei of the cortex also showed differential encoding of rate information, we measured LFPs from lemniscal auditory cortex (fields A1 and DC; n=29) and the paralemniscal ventral caudal belt (VCB; n=24) in response to the same click trains as described for the thalamus (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics for lemniscal and paralemniscal cortical responses). All latency and amplitude values were normalized with respect to values measured in the 2 Hz condition. The averaged LFPs in response to the second and third clicks within a train are plotted at each of the three repetition rates as a function of time in Figure 3.

Table 2.

| 2 Hz | 5 Hz | 8 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clicks 2 and 3 LFP | |||

| Peak Amplitude | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 227.21 (245.492) μV | 301.33 (299.519) μV | 171.09 (170.369) μV |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 128.14 (148.968) μV | 157.09(192.412) μV | 115.16 (156.257) μV |

| Peak Latency | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 20.431 (5.272) ms | 22.986 (6.892) ms | 25.248 (7.329) ms |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 27.604 (6.806) ms | 30.45 (7.111) ms | 33.671 (7.823) ms |

| Half-Peak Latency | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 16.069 (3.973) ms | 18.331 (5.168) ms | 19.576 (5.101) ms |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 21.612 (5.392) ms | 24.229 (5.814) ms | 26.525 (6.609) ms |

| Steady-State LFP | |||

| Peak Amplitude | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 249.98 (233.654) μV | 160.31 (154.973) μV | 111.06 (119.945) μV |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 134.1 (144.903) μV | 182.36 (261.226) μV | 55.82 (46.950) μV |

| Peak Latency | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 20.01 (5.207) ms | 22.183 (5.941) ms | 20.7 (5.602) ms |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 26.688 (6.756) ms | 30.589 (9.107) ms | 27.686 (9.515) ms |

| Half-Peak Latency | |||

| Lemniscal mean (SD) | 15.603 (3.714) ms | 16.607 (4.055) ms | 15.148 (3.211) ms |

| Paralemniscal mean (SD) | 21.2 (5.472) ms | 24.428 (7.962) ms | 22.822 (8.173) ms |

Figure 3. Cortical LFPs to click trains.

(a–b) Two representative lemniscal cortical responses (A1 and DC) and (c) a representative paralemniscal (VCB) cortical response. Plots represent the average local field potential in response to clicks 2 and 3 in a train. Figure 3 insets: plots represent LFPs in response to the first click in a train measured in lemniscal cortex (Figure 3a, 4b insets) and VCB (Figure 3c inset). The circles on the plots indicate the peak, base and half-peak measures recorded for each LFP at each click rate.

For lemniscal responses, the relationship between click rate and response latency was varied: one third of lemniscal cortical responses were latency-invariant for increasing click rate (Figure 3a) while the remaining responses were latency-variant in a manner similar to paralemniscal thalamus, with increasing click rates inducing longer response lags (Figure 3b). All latency-invariant lemniscal responses had short (absolute) latency responses. Statistical analysis across all lemniscal cortex responses revealed a significant increase in response latency for increasing click rate (F2,56 = 73.189; P<0.0001; Figure 4a). Post hoc pairwise comparisons of lemniscal latencies indicated significantly later responses for 5 Hz compared to 2 Hz click rates (t = 7.693, P<0.0001) as well as 8 Hz compared to 5 Hz click rates (t = 6.608, P<0.0001). Paralemniscal cortical response latencies also varied according to click rate, with increasing stimulus rates resulting in longer response latencies (F2,46 = 78.573; P<0.0001; Figure 3c). Unlike lemniscal cortex, all paralemniscal penetrations followed this pattern. Post hoc pairwise comparisons of paralemniscal latencies indicated significantly later responses for 5 Hz compared to 2 Hz click rates (t = 7.230, P<0.0001) as well as 8 Hz compared to 5 Hz click rates (t = 6.346, P<0.0001). Results from latency at half-peak were identical to those described for latency at peak (effect of click rate on lemniscal LFPs: F2,56 = 52.020, P<0.0001; effect of click rate on paralemniscal LFPs: F2,46 = 77.559, P<0.0001). There was no statistical difference between lemniscal and paralemniscal cortical response latencies for increasing stimulus rates (effect of pathway: F1,51 = 0.002; P=0.966, not significant).

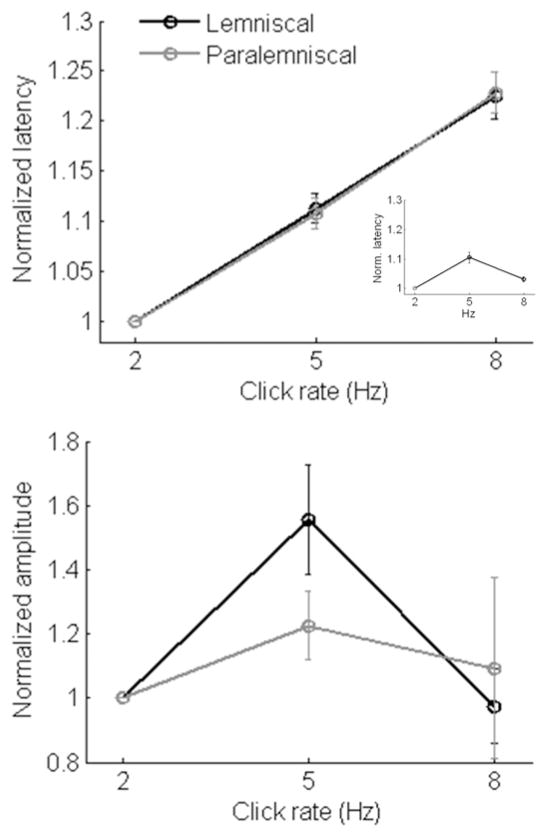

Figure 4. Mean Cortical LFPs.

Mean (± SE) local field potential (a) latency and (b) amplitude for lemniscal and paralemniscal cortical responses. Figure 4a inset: mean “steady-state” cortical LFP latencies.

We quantified the effect of click rate on peak LFP amplitudes measured at cortex in response to the second and third click in the trains (Figure 4b). For lemniscal cortex, there was a significant effect of rate on normalized LFP amplitude (F2,56 = 11.356; P<0.0001). Specifically, lemniscal cortical LFPs indicated a preference for the 5 Hz condition, with LFP amplitudes increasing significantly between 2 Hz and 5 Hz (t = 3.289, P=0.003) and decreasing between 5 Hz and 8 Hz (t = 4.752, P<0.0001). The preference for 5 Hz based on LFP amplitude may reflect a rate code in lemniscal auditory cortex. Despite a similar trend of preference for 5 Hz for paralemniscal cortex, there was no effect of click rate on normalized LFP amplitude (F2,46 = 0.384; P=0.683). This failure to reach statistical significance can be explained by the fact that approximately half of the paralemniscal LFP amplitudes indicated a preference for the 5 Hz condition, similar to lemniscal cortical responses, while the other half of the responses preferred the 2 Hz condition. There was no statistical difference between lemniscal and paralemniscal cortical response amplitudes for increasing stimulus rates (LFP amplitude rate * pathway interaction, F1,51 = 0.314, P=0.577).

Two important differences were identified between cortical LFPs to the second and third clicks in the train and last-one-second (steady-state) LFPs. First, some paralemniscal LFP amplitudes diminished into the noise floor towards the end of the 5 and 8 Hz click trains, consistent with an adaptation process. This only affected steady-state responses and occurred in 25% of paralemniscal sites in response to the 5 Hz condition and 42% of paralemniscal sites in response to 8 Hz click trains. Responses from these sites were not included in the steady-state statistical analysis. The second important difference between steady-state cortical LFPs and LFPs to the second and third clicks in the train was that steady-state LFP latencies consistently decreased between the 5 Hz and 8 Hz conditions for both lemniscal and paralemniscal recording sites (Figure 4a inset) in contrast to the systematic increase in latency with increasing click rate seen in LFPs to the second and third clicks in a train (Figure 4a, main figure).

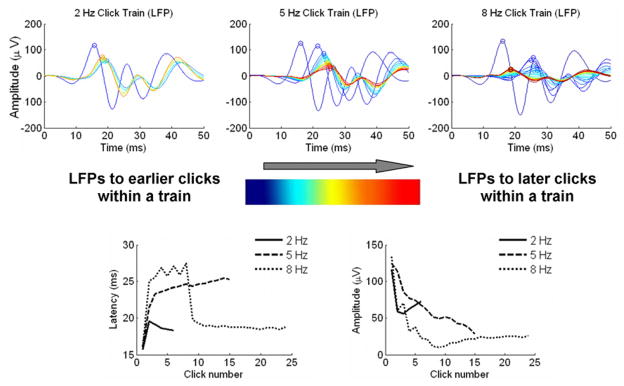

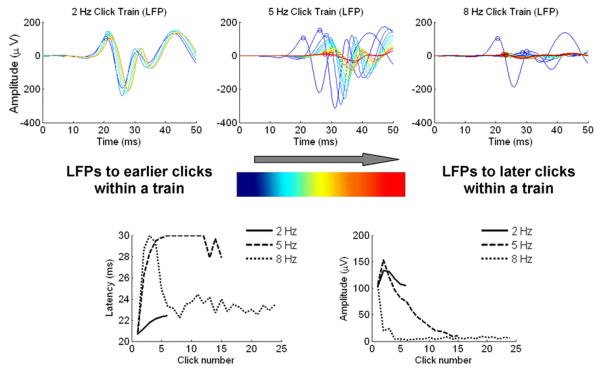

Due to the different rate-latency pattern between LFPs to the second and third clicks in the train and steady-state cortical LFPs, we investigated the dynamics of lemniscal LFPs. Results indicate two distinct patterns of activation across the three click rate conditions for lemniscal recording sites. In one pattern, lemniscal peak LFP latencies remained extremely consistent, in this case between 10–11 msec, across all clicks in all three rate conditions (Figure 5). This occurred in 34% of lemniscal recording sites. A second pattern of activation revealed dynamic shifts in LFP latency that were evident both within a click rate condition and across rate conditions (Figure 6). For example, in the 2 Hz click rate condition, following the first click, LFP peak latencies are relatively static throughout the click train. In contrast, LFP peak latencies in the 5 Hz condition gradually shift during the first 5 clicks in the train before settling at a latency of 24 msec. In the 8 Hz click train condition, LFP peak latencies initially jump to a latency of 27 msec before settling to a latency of 19 msec by click nine. These particular patterns were seen in 66% of lemniscal recording sites. We also investigated the dynamics of paralemniscal LFPs (Figure 7). In the 2 Hz click rate condition, peak LFP latencies again are fairly static throughout the click train. In the 5 Hz click rate condition, peak LFP latencies make a large shift to 30 msec by 1 second into the 3 second click train. In the 8 Hz click rate condition, LFPs adapt immediately after the first click in the train. These particular patterns were seen in 85% of paralemniscal recording sites.

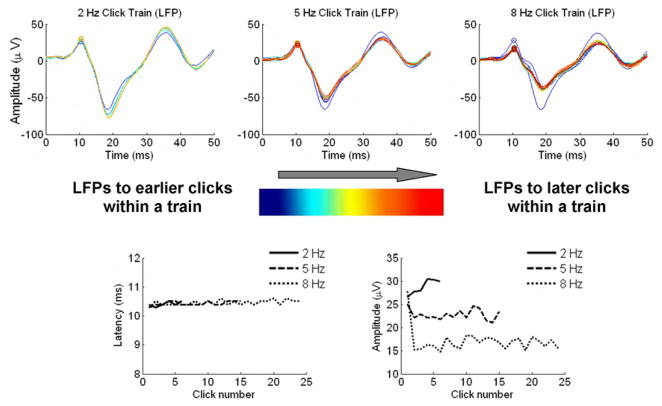

Figure 5. Lemniscal cortical dynamics, pattern #1.

Top: overlays of LFPs from a lemniscal recording site in response to each click in a click train for the 2 Hz condition (left), 5 Hz condition (center) and 8 Hz condition (right). LFPs in response to earlier clicks in the train are plotted in blue while responses to the last clicks in the train are plotted in red. Bottom left: peak LFP latency as a function of click number for the three rate conditions. Bottom right: peak LFP amplitude as a function of click number for the three rate conditions.

Figure 6. Lemniscal cortical dynamics, pattern #2.

Top: overlays of LFPs from a lemniscal recording site in response to each click in a click train for the 2 Hz condition (left), 5 Hz condition (center) and 8 Hz condition (right). LFPs in response to earlier clicks in the train are plotted in blue while responses to the last clicks in the train are plotted in red. Bottom left: peak LFP latency as a function of click number for the three rate conditions. Bottom right: peak LFP amplitude as a function of click number for the three rate conditions.

Figure 7. Paralemniscal cortical dynamics.

Top: overlays of LFPs from a paralemniscal recording site in response to each click in a click train for the 2 Hz condition (left), 5 Hz condition (center) and 8 Hz condition (right). LFPs in response to earlier clicks in the train are plotted in blue while responses to the last clicks in the train are plotted in red. Bottom left: peak LFP latency as a function of click number for the three rate conditions. Bottom right: peak LFP amplitude as a function of click number for the three rate conditions.

4. Discussion

To investigate central auditory system coding of slow acoustic rates, we measured responses from lemniscal and paralemniscal auditory thalamus and cortex in guinea pig to click train stimuli with rates between 2–8 Hz. At the level of thalamus, lemniscal neurons were latency invariant regardless of click rate while paralemniscal neurons showed systematic latency shifts with increasing temporal rate. At the level of cortex, some lemniscal responses were rate invariant while others showed dynamic latency shifts. In contrast, paralemniscal sites in cortex consistently showed latency shifts with increasing rate. Amplitudes of both lemniscal and paralemniscal thalamus and cortex were rate variant.

4.1 Comparison to previous studies of the auditory system

4.1.1 Lemniscal pathway

Slow temporal rates have been studied extensively in the lemniscal pathway of the auditory system (thalamus: (Creutzfeldt, et al., 1980; Miller, et al., 2002; Preuss, et al., 1990; Rouiller, et al., 1982; Rouiller, et al., 1981; Vernier, et al., 1957); cortex: (Bieser, et al., 1996; Creutzfeldt, et al., 1980; Eggermont, 1991; Goldstein, et al., 1959; Lu, et al., 2000; Lu, et al., 2001; Phillips, et al., 1989; Steinschneider, et al., 1998)). At the level of thalamus, many studies have investigated the representation of repetition rate with an emphasis on identifying the maximum frequency to which these neurons are able to synchronize, however the current study is the first systematic description of onset latencies for various click rates in lemniscal thalamus. On the other hand, the current results from lemniscal cortex corroborate previous descriptions of latency shifts for increasing stimulus rates. Specifically, single-unit responses measured in auditory cortex of anesthetized cat showed systematic latency shifts for increasing stimulus rates similar to those shown here (Phillips, et al., 1989). In a similar study in unanesthetized rat, however, no latency shifts were shown for rates below 20 Hz (Anderson, et al., 2006). A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that spike timing of a particular unit in the latter study did not appear to be analyzed with respect to its own timing at other rates (i.e., it is not clear whether repeated measures statistics were used). Therefore, relatively small increases in spike-timing for increasing rates seen within individual neurons may have been overwhelmed by the variability of spike times between neurons.

It remains a possibility that the pattern of latency shifts for increasing click rates is due to the use of anesthesia. Previous studies have shown that neural adaptation at lower frequencies in the somatosensory thalamus and cortex increases when the experimental animal is in a quiescent state (i.e., when anesthetized) relative to an active state (Castro-Alamancos, 2002). Therefore, it is conceivable that LFP latency shifts seen at higher-frequency click rates in the current study are influenced by anesthetic state. This appears to be an unlikely explanation of the current results, however, since only some of the neural responses in thalamus and cortex exhibited latency shifts despite controlling for anesthetic state (to the best of our ability) across all neurophysiological measurements.

4.1.2 Paralemniscal pathway

Physiological properties of paralemniscal nuclei of thalamus and cortex in the guinea pig auditory system have been described in a number of previous studies (He, 2002; He, 2003a; He, 2003b; Redies, et al., 1991; Redies, et al., 1989a; Wallace, et al., 2000). Studies in paralemniscal thalamus have shown that these nuclei may be responsible for coding acoustic onset and offset information and play a role in the gating of acoustic information to and from cortex (He, 2002; He, 2003a; He, 2003b). To our knowledge, only one previous study has examined extralemniscal processing of acoustic rate information. This study showed that neurons in the thalamic reticular nucleus exhibit increasing response latencies with shorter inter-click intervals (Yu, et al., 2009b). Results from the current study are similar to these results from the reticular nucleus, and show that these response properties are also evident in paralemniscal nuclei within the medial geniculate body of the thalamus. A major difference between these studies, however, is the fact that in this previous study (Yu, et al., 2009b) responses were analyzed for the steady-state portion of the click train, defined as responses to click numbers 11 through 30, whereas in the current study we have analyzed responses to clicks two and three of the click train. Given the rapidity with which responses in the current study reflect click rate, the present results suggest an efficient mechanism that could conceivably track slow rate information in biologically-important acoustic signals.

A question raised by this work involves the hierarchy of the paralemniscal auditory pathway at the levels of auditory thalamus and cortex. While it is tempting to consider paralemniscal pathways as separate neural entities from the lemniscal pathway, this may be an oversimplification of a more complex junction in the ascending auditory system. While it has been shown that the VCB in guinea pig receives its primary thalamic input from MGs and MGcm, it also receives projections from adjacent lemniscal cortex. Similar connections have been shown in marmosets (de la Mothe, et al., 2006a; de la Mothe, et al., 2006b). Since the current results show that paralemniscal thalamus/cortex and lemniscal cortex show similar sensitivity to slow rates, these data do not address which input might dominate paralemniscal cortex. It is hoped that future studies may begin to disentangle the relative interactions of these auditory structures.

4.2 Comparison to the rat trigeminal system

Previous findings from the rat trigeminal system indicate discrete properties for lemniscal and paralemniscal neurons of thalamus and cortex (Ahissar, et al., 1997; Ahissar, et al., 2000; Sosnik, et al., 2001), for review see (Ahissar, et al., 2001). In both thalamus and cortex, the lemniscal pathway showed sensitivity to spatial organization of the periphery (i.e., vibrissae location) and fixed time-locking for various stimulus rates while the paralemniscal system was insensitive to spatial organization of the periphery but showed variable time-locking. Based on these response characteristics it was proposed that these parallel pathways serve different neural functions related to exploration and active touch during whisking. Specifically, it was proposed that lemniscal neurons perform spatial processing while paralemniscal neurons perform low-frequency temporal processing.

Results from the current study show both similarities and differences relative to those shown in studies of the rat trigeminal system. Similar to the trigeminal system, responses measured in auditory thalamus indicate that slow rates are represented differently in lemniscal and paralemniscal pathways, with paralemniscal responses indicating sensitivity to slow rates. An important difference between results from rat trigeminal system and the current results from the auditory system is the response of lemniscal cortical neurons to slow temporal rates. In the somatosensory system, lemniscal cortex (layers 4 and 5b) was insensitive to slow temporal rate information while in the auditory system the majority of these sites were sensitive to slow temporal rate. A potential explanation for this discrepancy is that sensory cortex is more remote from the periphery in the auditory system relative to somatosensory cortex. Consequently, lemniscal auditory cortex could represent a higher level of processing relative to the somatosensory cortex that is responsible for the integration of lemniscal and paralemniscal temporal rate responses. Moreover, the additional processing of slow rates in lemniscal cortex of the auditory system could reflect the import of the temporal envelope of communication calls for perception (Drullman, et al., 1994). Finally, any differences between somatosensory and auditory response characteristics could be due to the nature of the information being processed in these two systems.

4.3 Auditory coding of slow rates: a new hypothesis

Previous studies have demonstrated that acoustic rate information may be represented by the auditory thalamus (Bartlett, et al., 2007) and cortex (Lu, et al., 2001) with a two-stage mechanism. These studies suggest that slow acoustic rates (< ~50 Hz in cortex; < ~200 Hz in thalamus) are represented “explicitly” according to the temporal discharge patterns of synchronized lemniscal auditory neurons, while faster rates are represented “implicitly” according to the average discharge rate of non-synchronized neurons. Therefore, this model proposes that two populations of neurons in auditory thalamus and cortex facilitate the representation of a wide range of temporal features in acoustical signals in a complementary fashion. The goal of the current study was to investigate neural mechanisms that underlie the perception of slow acoustic rates.

Results described in the present study suggest that temporally synchronized neurons of a paralemniscal pathway, as well as lemniscal cortex, differentially represent specific low-frequency stimulus rates (<10 Hz) with discrete shifts in response latencies. These latency shifts may provide a neural code for slow rate information. Rate-sensitive neurons showed selectivity to particular rates within a short time period (by the third click in a train) in both thalamus and cortex. Consequently, results from paralemniscal neurons of thalamus and cortex enable a new hypothesis for the role of this pathway in the representation of biologically relevant acoustic signals. Specifically, paralemniscal pathways may be involved in the representation of low-frequency temporal information. Moreover, lemniscal cortex is also implicated in the processing of these slow temporal features. An alternative explanation for these results is that paralemniscal and lemniscal nuclei of the thalamus (Anderson, et al., 2009; Yu, et al., 2009a) and cortex (Ulanovsky, et al., 2003; Ulanovsky, et al., 2004) exhibit different patterns of stimulus-specific adaptation in response to repeated stimuli. It is hoped that future studies can address the extent to which adaptation influences the responses measured in the current study.

4.4 Limitations of the current work

A caveat for this work is the potential impact of ketamine/xylazine anesthesia on the electrophysiological signal. Ketamine is a known NMDA receptor antagonist, and there is evidence that collicular synaptic inputs to the rat MGB have different proportions of AMPA and NMDA components of the EPSPs when comparing lemniscal and paralemniscal auditory thalamus (Hu, et al., 1994). Therefore, the use of ketamine could potentially preferentially skew responses in lemniscal versus paralemniscal thalamus.

A second caveat for this work is the use of click stimuli as a means of examining temporal response properties in the ascending auditory system. One can argue that wideband sounds are not representative of most animal communication calls, which are typically continuously amplitude-modulated and not often broadband. Nevertheless, click stimuli have been used extensively in the literature to describe temporal processing mechanisms in both thalamus (Rouiller, et al., 1982; Rouiller, et al., 1981; Vernier, et al., 1957) and cortex (Eggermont, 1991; Eggermont, 1992; Eggermont, 1998; Eggermont, 2002; Eggermont, et al., 1995; Lu, et al., 2000; Lu, et al., 2001; Steinschneider, et al., 1998), and the use of click trains in the current stimuli enabled comparison with these previous studies. It is hoped that future studies utilizing additional stimulus conditions will be conducted to examine the generalizability of the current findings.

A final caveat for this work is that the systematic latency shifts of LFPs based on click rate described in this work do not necessarily mean that LFP latency is the mechanism by which rate info is represented. LFP shifts may be byproducts of a different underlying mechanism. Further elaboration is necessary to rule out the possibility that the observed latency shifts are based on other factors.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have shown dissociation between lemniscal and paralemniscal pathways in the encoding of slow rates in the auditory thalamus similar to findings from the rat trigeminal system. Moreover, we have shown convergence of these two rate representations at the level of lemniscal auditory cortex. These data suggest that this paralemniscal thalamocortical pathway may be involved in the representation of low-frequency temporal information.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 DC01510-10 and National Organization for Hearing Research grant 340-B208. We thank E. Ahissar for critical reviews of this manuscript and C. Warrier for assistance with data collection.

Abbreviations

- MGv

medial geniculate body of thalamus

- A1

primary auditory cortex

- DC

dorsocaudal field of cortex

- MGs

shell nucleus of the medial geniculate body

- VCB

ventral caudal belt of auditory cortex

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahissar E, Zacksenhouse M. Temporal and spatial coding in the rat vibrissal system. Prog Brain Res. 2001;130:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(01)30007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahissar E, Haidarliu S, Zacksenhouse M. Decoding temporally encoded sensory input by cortical oscillations and thalamic phase comparators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11633–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahissar E, Sosnik R, Haidarliu S. Transformation from temporal to rate coding in a somatosensory thalamocortical pathway. Nature. 2000;406:302–6. doi: 10.1038/35018568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA, Christianson GB, Linden JF. Stimulus-specific adaptation occurs in the auditory thalamus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7359–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0793-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SE, Kilgard MP, Sloan AM, Rennaker RL. Response to broadband repetitive stimuli in auditory cortex of the unanesthetized rat. Hear Res. 2006;213:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett EL, Wang X. Neural representations of temporally modulated signals in the auditory thalamus of awake primates. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1005–17. doi: 10.1152/jn.00593.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieser A, Muller-Preuss P. Auditory responsive cortex in the squirrel monkey: neural responses to amplitude-modulated sounds. Exp Brain Res. 1996;108:273–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00228100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alamancos MA. Different temporal processing of sensory inputs in the rat thalamus during quiescent and information processing states in vivo. J Physiol. 2002;539:567–78. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzfeldt O, Hellweg FC, Schreiner C. Thalamocortical transformation of responses to complex auditory stimuli. Exp Brain Res. 1980;39:87–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00237072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J, Nicol T, King C, Zecker SG, Kraus N. Effects of noise and cue enhancement on neural responses to speech in auditory midbrain, thalamus and cortex. Hear Res. 2002;169:97–111. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mothe LA, Blumell S, Kajikawa Y, Hackett TA. Cortical connections of the auditory cortex in marmoset monkeys: core and medial belt regions. J Comp Neurol. 2006a;496:27–71. doi: 10.1002/cne.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mothe LA, Blumell S, Kajikawa Y, Hackett TA. Thalamic connections of the auditory cortex in marmoset monkeys: core and medial belt regions. J Comp Neurol. 2006b;496:72–96. doi: 10.1002/cne.20924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond ME, Armstrong-James M. Role of parallel sensory pathways and cortical columns in learning. Concept Neurosci. 1992;3:55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Drullman R, Festen JM, Plomp R. Effect of temporal envelope smearing on speech reception. J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;95:1053–64. doi: 10.1121/1.408467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Rate and synchronization measures of periodicity coding in cat primary auditory cortex. Hear Res. 1991;56:153–67. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Stimulus induced and spontaneous rhythmic firing of single units in cat primary auditory cortex. Hear Res. 1992;61:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90029-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Representation of spectral and temporal sound features in three cortical fields of the cat. Similarities outweigh differences. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2743–64. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Temporal modulation transfer functions in cat primary auditory cortex: separating stimulus effects from neural mechanisms. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:305–21. doi: 10.1152/jn.00490.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ, Smith GM. Synchrony between single-unit activity and local field potentials in relation to periodicity coding in primary auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:227–45. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JMH, Kiang NYS, Brown RM. Responses of the Auditory Cortex to Repetitive Acoustic Stimuli. J Acoust Soc Am. 1959;31:356–364. [Google Scholar]

- He J. OFF responses in the auditory thalamus of the guinea pig. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2377–86. doi: 10.1152/jn.00083.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. Corticofugal modulation on both ON and OFF responses in the nonlemniscal auditory thalamus of the guinea pig. J Neurophysiol. 2003a;89:367–81. doi: 10.1152/jn.00593.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. Slow oscillation in non-lemniscal auditory thalamus. J Neurosci. 2003b;23:8281–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-23-08281.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Hashikawa T. Connections of the dorsal zone of cat auditory cortex. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998;400:334–48. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19981026)400:3<334::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Hashikawa T, Ojima H, Kinouchi Y. Temporal integration and duration tuning in the dorsal zone of cat auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2615–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02615.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Senatorov V, Mooney D. Lemniscal and non-lemniscal synaptic transmission in rat auditory thalamus. J Physiol. 1994;479 (Pt 2):217–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huetz C, Philibert B, Edeline JM. A spike-timing code for discriminating conspecific vocalizations in the thalamocortical system of anesthetized and awake guinea pigs. J Neurosci. 2009;29:334–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3269-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C, Nicol T, McGee T, Kraus N. Thalamic asymmetry is related to acoustic signal complexity. Neurosci Lett. 1999;267:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaki H, Hashikawa T, He J, Jones EG. Tonotopic organization of auditory cortical fields delineated by parvalbumin immunoreactivity in macaque monkeys. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;386:304–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Wang X. Temporal discharge patterns evoked by rapid sequences of wide- and narrowband clicks in the primary auditory cortex of cat. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:236–46. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Liang L, Wang X. Temporal and rate representations of time-varying signals in the auditory cortex of awake primates. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1131–8. doi: 10.1038/nn737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee T, Kraus N, King C, Nicol T, Carrell TD. Acoustic elements of speechlike stimuli are reflected in surface recorded responses over the guinea pig temporal lobe. J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;99:3606–14. doi: 10.1121/1.414958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Escabi MA, Read HL, Schreiner CE. Spectrotemporal receptive fields in the lemniscal auditory thalamus and cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:516–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.00395.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DP, Hall SE, Hollett JL. Repetition rate and signal level effects on neuronal responses to brief tone pulses in cat auditory cortex. J Acoust Soc Am. 1989;85:2537–49. doi: 10.1121/1.397748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss A, Muller-Preuss P. Processing of amplitude modulated sounds in the medial geniculate body of squirrel monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 1990;79:207–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00228890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschecker JP, Tian B, Pons T, Mishkin M. Serial and parallel processing in rhesus monkey auditory cortex. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;382:89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redies H, Brandner S. Functional organization of the auditory thalamus in the guinea pig. Exp Brain Res. 1991;86:384–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00228962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redies H, Sieben U, Creutzfeldt OD. Functional subdivisions in the auditory cortex of the guinea pig. J Comp Neurol. 1989a;282:473–88. doi: 10.1002/cne.902820402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redies H, Brandner S, Creutzfeldt OD. Anatomy of the auditory thalamocortical system of the guinea pig. J Comp Neurol. 1989b;282:489–511. doi: 10.1002/cne.902820403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S. Temporal information in speech: acoustic, auditory and linguistic aspects. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1992;336:367–73. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1992.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller E, de Ribaupierre F. Neurons sensitive to narrow ranges of repetitive acoustic transients in the medial geniculate body of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1982;48:323–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00238607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller E, de Ribaupierre Y, Toros-Morel A, de Ribaupierre F. Neural coding of repetitive clicks in the medial geniculate body of cat. Hear Res. 1981;5:81–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(81)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnik R, Haidarliu S, Ahissar E. Temporal frequency of whisker movement. I. Representations in brain stem and thalamus. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:339–53. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinschneider M, Reser DH, Fishman YI, Schroeder CE, Arezzo JC. Click train encoding in primary auditory cortex of the awake monkey: evidence for two mechanisms subserving pitch perception. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;104:2935–55. doi: 10.1121/1.423877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suta D, Kvasnak E, Popelar J, Syka J. Representation of species-specific vocalizations in the inferior colliculus of the guinea pig. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:3794–808. doi: 10.1152/jn.01175.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulanovsky N, Las L, Nelken I. Processing of low-probability sounds by cortical neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:391–398. doi: 10.1038/nn1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulanovsky N, Las L, Farkas D, Nelken I. Multiple time scales of adaptation in auditory cortex neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:10440–10453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1905-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernier VG, Galambos R. Response of single medial geniculate units to repetitive click stimuli. Am J Physiol. 1957;188:233–7. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1957.188.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MN, Rutkowski RG, Palmer AR. Identification and localisation of auditory areas in guinea pig cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2000;132:445–56. doi: 10.1007/s002210000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lu T, Bendor D, Bartlett E. Neural coding of temporal information in auditory thalamus and cortex. Neuroscience. 2008;157:484–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey TA. In: Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Adelman G, Smith B, editors. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1997. pp. 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Yu XJ, Xu XX, He S, He J. Change detection by thalamic reticular neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2009a;12:1165–70. doi: 10.1038/nn.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XJ, Xu XX, Chen X, He S, He J. Slow recovery from excitation of thalamic reticular nucleus neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2009b;101:980–7. doi: 10.1152/jn.91130.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]