Abstract

Development of low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) based treatment strategies for a variety of orthopaedic issues requires better understanding of mechano-transduction and bone adaptation. Our overall goal was to study the tissue and molecular level changes in cortical bone in response to low-strain vibration (LSV: 70 Hz, 0.5 g, 300 με) and compare these to changes in response to a known anabolic stimulus: high-strain compression (HSC: rest inserted loading, 1000 με). Adult (6–7 month) C57BL/6 mice were used for the study and non-invasive axial compression of the tibia was used as a loading model. We first studied bone adaptation at the tibial mid-diaphysis, using dynamic histomorphometry, in response to daily loading of 15 min LSV or 60 cycles HSC for 5 consecutive days. We found that bone formation rate and mineral apposition rate were significantly increased in response to HSC but not LSV. The second aim was to compare chemo-transport in response to 5 min of LSV versus 5 min (30 cycles) of HSC. Chemo-transport increased significantly in response to both loading stimuli, particularly in the medial and the lateral quadrants of the cross section. Finally, we evaluated the expression of genes related to mechano-responsiveness, osteoblast differentiation, and matrix mineralization in tibias subjected to 15 min LSV or 60 cycles HSC for 1 day (4-hour time point) or 4 consecutive days (4-day time point). The expression level of most of the genes remained unchanged in response to LSV at both time points. In contrast, the expression level of all the genes changed significantly in response to HSC at the 4-hour time point. We conclude that short-term, low-strain vibration results in increased chemo-transport, yet does not stimulate an increase in mechano-responsive or osteogenic gene expression, and cortical bone formation in tibias of adult mice.

Keywords: Bone adaptation, Mechanical loading, Mechanotransduction, Low-strain vibration, Chemo-transport, Gene expression

Introduction

Dynamic mechanical loading is known to influence bone growth and remodeling. This influence can be harnessed to develop non-pharmacological interventions to address clinical challenges such as osteoporosis, fracture healing, implant integration, and disuse or age-related osteopenia. Since the socio-economic costs associated with these pathologies are severe, significant effort has been devoted to better understand bone adaptation in response to dynamic loading and the underlying bio-physical and biochemical mechanisms.

Of the various dynamic loading modalities, clinically relevant high-frequency, low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) has gained attention in recent years [1]. However, initial attempts to stimulate bone formation using such loading have not been uniformly successful and the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. A number of studies have demonstrated the anabolic potential of vibrational loading [2–5]. However, when LMMS is delivered by whole-body vibration (WBV) the strain imparted at the mid-diaphysis (~10 με) is much lower than that required to maintain bone mass as predicted by the daily stress stimulus theory of bone adaptation [6]. Hence the reported effects of WBV have been mainly restricted to metaphyseal and epiphyseal trabecular bone, skeletal sites at which the in vivo strain engendered by the loading cannot be controlled or measured. Therefore, although WBV loading might prove beneficial in treating osteoporosis, its use as a loading modality to study the mechanisms underlying high-frequency LMMS-related bone adaptation is limited. To overcome this limitation we developed a vibrational modality with the capacity to impart mid-diaphyseal strain greater than that required to maintain bone mass as predicted by daily stress stimulus theory [7]. However, our initial attempt at stimulating cortical bone formation with such low-strain vibration (LSV; 300 με at 70 Hz) in the tibias of adult mice met with little success [8]. The results of that study were confounded by systemic bone loss, possibly due to aging and an extended period (35 days) of daily anesthesia. The short-term bone formation response to LSV loading has not been described and would help us to better asses the anabolic potential of LSV.

One of the biophysical mechanisms suggested to be involved with bone mechano-transduction is load-induced interstitial fluid flow in the lacunar-cannalicular porosity [9–12]. It is postulated that the osteocytes sense the changes in chemo-transport, strain and/or membrane potential associated with this fluid flow and trigger a remodeling response. Although theoretical models have been developed to predict interstitial fluid flow in response to dynamic loading [13, 10], in vivo measurement of the flow itself has not been possible and will have to wait for significant advances in imaging techniques. Nonetheless, infiltration of tracer in bone porosities is considered to be a good indicator of the interstitial fluid flow and the associated chemo-transport [14]. Increased tracer infiltration in response to high-strain dynamic loading has been observed in the case of four-point bending of the rat tibia [15] and axial loading of the rat ulna [16]. However tracer infiltration in response to high-frequency LMMS has not been reported.

Further insight into mechano-transduction can be gained by studying gene expression in bones in response to loading. A number of in vivo studies have characterized gene expression in response to dynamic mechanical loading [17–20]. High-strain dynamic loading is known to alter expression of genes involved with prostaglandin E2 synthesis (Cox-2) [18], osteoblast differentiation (Bmp-2, Runx-2, Osx) and mineralization (Bsp, Ocn, Alp) [19]. Recently the Wnt/Lrp5 signaling pathway was shown to be involved with osteocyte mechanotransduction [21] and it was reported that the expression of genes Sost and Dkk1, associated with this pathway, is altered by high-strain dynamic loading [20]. Whereas changes in gene expression pattern in response to high-strain low-frequency loading have been reported by several authors we are aware of only one study related to high-frequency LMMS. Judex et al. reported that expression of bone formation and bone resorption related genes in tibia of adult BALB/c mice did not change significantly in response to 4 days of high-frequency LMMS loading (45 Hz, 0.3g, 10 min/day), whereas the expression of MMP-2 and RANKL was significantly up regulated following 21 days of loading [5]. Shorter term changes in gene expression in response to low-strain, high-frequency loading have not been reported.

The overall goal of this study was to characterize the short-term tissue and molecular level response of cortical bone subjected to low-strain vibration (LSV) and compare it with the response of cortical bone subjected to high-strain compression (HSC- positive control). Specifically we assessed 1) bone formation using dynamic histomorphometry, 2) tracer infiltration, and 3) gene expression in response to the aforementioned loading stimuli.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Seventy-three, 3–4 month old C57BL/6 male mice were obtained from Harlan Bio-Products and were housed in humidity and temperature controlled animal facility throughout the duration of the study. The animals were allowed to mature to 6–7 months before being used for the study. Five or fewer animals were caged together, were provided with unlimited mouse chow and water, and were exposed to 12 hr dark/light cycle. Animals subjected to tracer infiltration or dynamic loading were anesthetized using isoflurane gas (2.5 % isoflurane in oxygen at 1.5 L/min), and were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Animal handling and experimentation was done in accordance with a protocol approved by Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

In vivo loading

High-strain compression (HSC)

Based on a method described previously [22], the right leg (loaded) of the anesthetized mouse was held between the actuator arms of servohydraulic material testing device (Instron 8841) using specially designed fixtures and was subjected to dynamic loading with peak load of 10.0 N (preload: 0.5 N, loading rate: 48 N/s, rest between consecutive cycles: 10 s). The left leg (non-loaded) served as a contra-lateral control [23]. The animals were given an intra-muscular injection of buprenex (0.03 ml/25 mg) following each loading session.

Five mice were used to determine the strain at anterior-medial tibial surface, 5 mm proximal to tibia fibula junction (TFJ) under the described loading. Immediately post mortem, a foil strain gauge (Tokyo Sukki Kenkyujo Ltd., FLK-1-11-1L) was attached at the site of interest and the hindlimb was subjected to loading. Strain signal was recorded using LabVIEW data acquisition unit (National Instruments SCXI-1321 and SCXI-112). The peak tensile strain magnitude engendered in response to HSC was estimated to be appx. 1000με.

Low-strain vibration (LSV)

Based on a method described previously [7], the right leg (loaded) of the anesthetized mouse was held between two posts in a similar alignment as used for HSC. The lower post supported the knee and was attached to a vibrating platform while the upper post (weight 125 g) was constrained to move vertically and rested on the ankle. The leg was subjected to axial vibrational loading (70 Hz, 0.5 g peak acceleration). The left leg (non-loaded) served as a contra-lateral control. The low-strain vibration loading leads to a dynamic strain magnitude of ~300 με at anterior-medial tibial plateau 5mm proximal to distal TFJ [8].

Dynamic Histomorphometry

Twenty mice were randomly divided into two groups: HSC and LSV. Starting at day 1, mice from HSC group were subjected to 10 minutes (60 cycles) of HSC loading and those from LSV group were subjected to 15 minutes (~63,000 cycles) of LSV loading, daily for 5 consecutive days. Mice from both groups were injected with calcein green (7.5 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich) and alizarin complexone (30 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich) intraperitoneally on day 4 and day 9, respectively. The mice were euthanized on day 11 and both tibias were harvested. The tibias were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde before being embedded in methyl methacrylate following standard procedures.

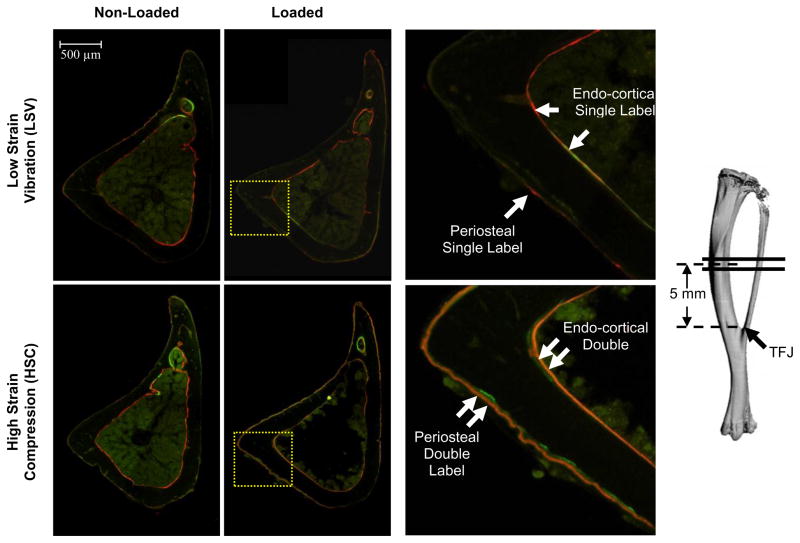

A 150 μm thick transverse section, 5 mm proximal to distal TFJ (Figure 1), was obtained from each tibia using an annular diamond saw (Lieca 1600SP) and was mounted on a glass slide using quick hardening mounting medium (Fluka 03989). The section was subsequently polished to a final thickness of ~30 μm using polishing paper of varying grit. Each section was imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX51 Inverted Microscope) at 10X magnification with two different filters: DAPI for calcein label and TRITC for alizarin label. A composite two-colored digital image was acquired (Olympus DP70) and analyzed using a commercial software application (Bioquant). The perimeter of unlabeled, single-labeled and double-labeled surface and the average distance between the double labels was quantified. Mineral apposition rate (MAR), bone formation rate (BFR/BS) and the ratio of mineralizing surface to bone surface (MS/BS) were determined [24].

Figure 1.

Periosteal and endo-cortical bone formation was stimulated in response to HSC but not in response to LSV. Images of the transverse section of tibial mid-diaphysis, were obtained using a fluorescence microscope. The mice were injected with calcein green on day 4 and alizarin complexone on day 9 from the start of loading (day 1). Comparison of the corresponding areas of the loaded sections from HSC and LSV group demonstrates the difference in amount of double labeled surface in response to the two loading modalities. The absence of an increase in endo-cortical and periosteal double labeled surface in case of LSV was evident.

Tracer Transport

Twenty-four mice were randomly divided into two groups: HSC and LSV. The tracer transport protocol used was a variation of that previously described [25]. The right jugular vein was exposed through a 15 mm incision in the neck above the right forelimb [26]. The jugular vein was isolated from the surrounding tissue and a suture was passed underneath the vessel. The tracer solution (0.3 ml/30 g 40kDa TRITC labeled Dextran [Invitrogen] in PBS at concentration 50mg/1.2ml) was slowly injected into the vein using a 29 gauge insulin syringe at a site upstream of the suture. The suture was tied off after the injection in order to avoid backflow. Within a minute following injection the mouse was subjected to either 30 cycles of HSC loading or 5 min of LSV loading. This lesser duration of loading was used to avoid saturation of lacunar-cannalicular porosity with the tracer solution. The animal was euthanized immediately after loading and both the tibias were harvested. The tibias were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde before being embedded in methyl methacrylate.

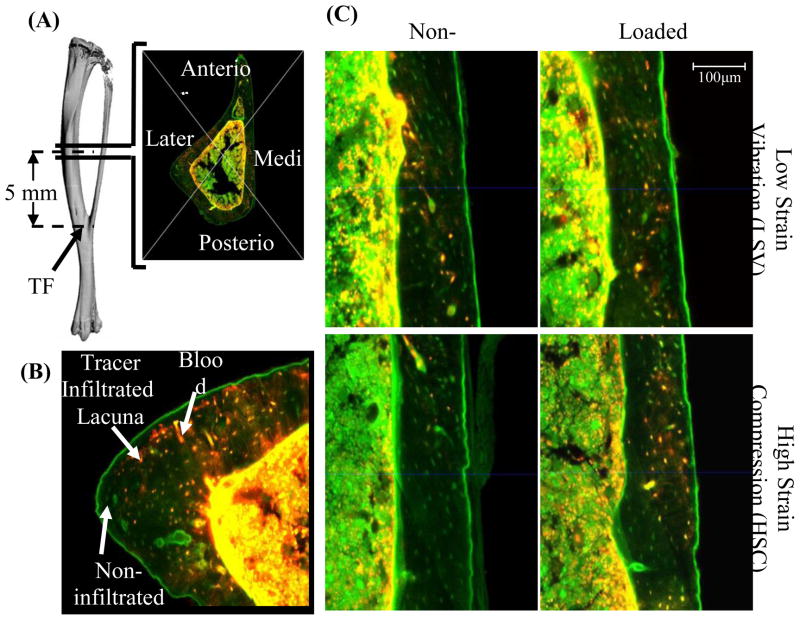

Two 150 μm thick transverse sections, 5 mm proximal to distal TFJ, were obtained from each tibia. A two-color fluorescence image (excitation at 488 nm and emission at 503–550 nm for auto-fluorescence and excitation at 574 nm and emission > 580 nm for TRITC fluorescence) of each section at 40X magnification was obtained using a confocal microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200 M). A customized image analysis program developed using MATLAB (Mathworks) was used for further analysis of the 8-bit digital image. The analysis involved rotation of the image so that the antero-medial tibial surface was oriented vertically (parallel to the Y-axis), determining the centroid of the cross section and dividing the cross section into four anatomical quadrants (Figure 3). Cortical bone area of each quadrant was determined and the approximate midpoints of both the infiltrated and non-infiltrated lacunae from each quadrant were manually identified. To clearly delineate infiltrated lacunae from the background noise the average value of the red channel intensity (range: 0–255) from a 3pixel × 3pixel square around the identified midpoint was estimated. The lacuna was considered infiltrated if this average value of color intensity was greater than 100. The average of the no. of infiltrated lacunae per unit area of the two transverse sections was determined for each quadrant and for the entire cross-section.

Figure 3.

Tracer infiltration in lacunar-cannalicular porosity of tibial mid-diaphysis is enhanced in response to both LSV and HSC. Mid-diaphyseal sections were imaged using confocal microscope with excitation frequency of 545nm for tracer (40kDa TRITC labeled dextran) and 478nm for autofluorescence. The centroid of each cross section was determined and image was divided into four anatomical quadrants (A). Cortical bone area of each quadrant was estimated and the infiltrated lacunae (orange) were identified from the non-infiltrated lacunae (green) and the blood vessels(B). Representative images of medial quadrant of loaded and non-loaded tibia from LSV and HSC group (C). Enhanced infiltration was evident in response to both the loading stimuli.

Gene Expression

Twenty-four mice were randomly divided into four groups: Mice from 4Hr HSC and 4Hr LSV group were subjected to 60 cycles of HSC loading and 15 min of LSV loading, respectively and were euthanized 4 hours post-loading. The mice from 4Day HSC and 4Day LSV group were subjected to daily loading of 60 cycles of HSC or 15 min of LSV for 4 consecutive days and were euthanized 4 hours after last loading session. The central portion (appx. 60–75 %) of both the tibias from each mouse was harvested within 8 min of euthanasia and was snap frozen using liquid nitrogen. The samples were stored at −80°C until pulverization.

RNA isolation was carried out using a previously described protocol [27]. Briefly each sample was pulverized and the fine powder was stabilized using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). DNA and proteins were precipitated out of the solution using chloroform (Sigma) and phase lock gel tube (PLG-heavy, Eppendorf). The RNA was further purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) as per the instructions provided. The purity and concentration of the isolated RNA was determined using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 3300, Thermo Scientific). 1 μg of purified RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using random primers and superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The quantitative real time RT-PCR reactions were carried out using 20 μl of final volume and 40 cycles of denaturing and annealing/elongation (7500 Real-Time PCR System, Applied Biosystems). SYBR green (Applied Biosystems) was used as a reporter agent. Expression of the genes Alp, Bmp-2, Bsp, Cox-2, Dkk1, Sost, Osx, Runx-2 and Ocn was studied. Cyclophillin was used as a housekeeping gene. The fold change in the expression level of a gene in the loaded limb relative to its expression in the non-loaded tibia was determined using 2−ΔΔCT method [28].

Statistical Analysis

Normal distribution of each dataset was determined using Anderson-Darling test. Students paired t-test was used for loaded vs. non-loaded comparisons and students unpaired t-test for comparisons of ipsilateral tibia between groups. Kruskal-Wallis and Wilcoxon Signed Rank test were used when one of the dataset did not follow normal distribution. Significance was defined at p < 0.05.

Results

Dynamic Histomorphometry

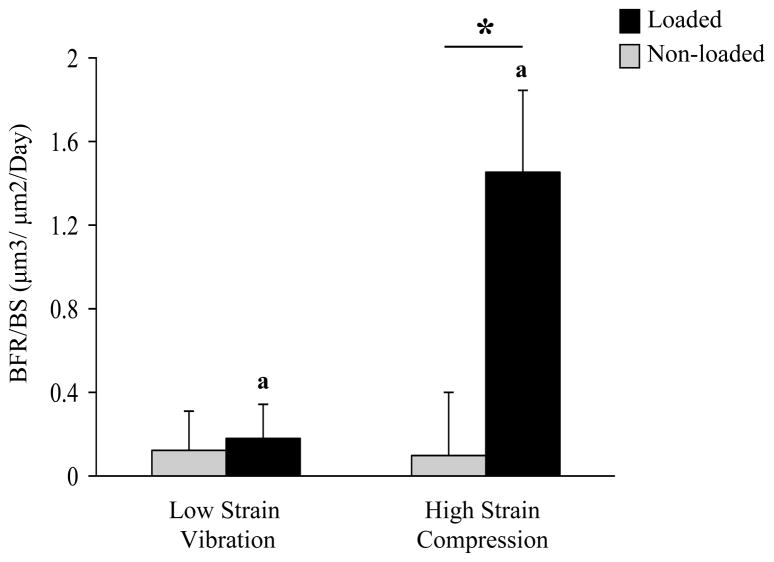

Short-term, low-strain vibration (LSV) did not induce significant changes in bone formation indices at either the periosteal or the endo-cortical surface, whereas indices were significantly increased in response to short-term, high-strain compression (HSC). At the periosteal surface BFR and MAR for the loaded limb of the HSC group were 1400 % and 850 % greater, respectively, than for the non-loaded contralateral control limb (Fig 2). BFR and MAR for loaded limb of the HSC group were also 700 % and 310 % greater, respectively, than for the loaded limb of LSV group. The endo-cortical surface showed similar increases in response to HSC (Table 1). The indices for the non-loaded limbs of the HSC and the LSV groups were not significantly different from each other. None of the cross sections showed presence of cracks or woven bone.

Figure 2.

Periosteal bone formation rate at the loaded and non-loaded tibial mid-diaphysis of the HSC and LSV group. Compared to the non-loaded contralateral control the histomorphometric indices for the loaded limb show little change in response to LSV where as they were significantly enhanced in response to HSC. Similar trend for the index was also observed at the endo-cortical surface.

*: significantly different from contralateral limb as determined by paired t-test.

a: significantly different from ipsilateral limb as determined by unpaired t-test.

Table 1.

Bone formation indices for endo-cortical and periosteal surface of cortical bone in response to % days of LSV and HSC.

| Loading Group | Limb Treatment | Endocortical | Periosteal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAR(μm/day) | MS/BS (%) | BFR/BS (μm3/μm2/day) | MAR (μm/day) | MS/BS (%) | BFR/BS (μm3/μm2/day) | ||

| Low-Strain Vibration | Loaded | 0.57b ± 0.98 | 34.80 ± 7.21 | 0.22b ± 0.39 | 0.67b ± 0.58 | 25.54b ± 3.96 | 0.18b ± 0.16 |

| Non-loaded | 0.98 ± 0.80 | 33.44 ± 5.49 | 0.35 ± 0.29 | 0.47 ± 0.69 | 25.03 ± 5.89 | 0.13 ± 0.18 | |

| High-Strain Compression | Loaded | 1.86a,b ± 1.21 | 39.56 ± 13.52 | 0.83a,b ± 0.62 | 2.72a,b ± 0.50 | 53.03a,b ± 9.30 | 1.46a,b ± 0.39 |

| Non-loaded | 0.75 ± 0.10 | 29.57 ± 8.22 | 0.25 ± 0.36 | 0.29 ± 0.90 | 26.96 ± 4.58 | 0.10 ± 0.31 | |

p<0.05 vs. non-loaded limb

p<0.05 vs. ipsilateral limb

Tracer Transport

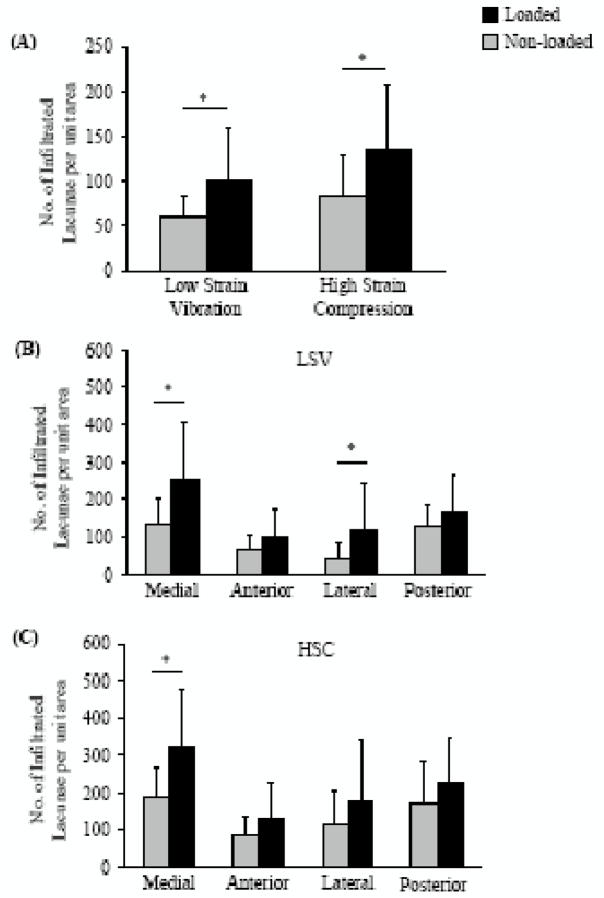

Tracer infiltration increased significantly in response to both LSV and HSC loading. The number of infiltrated lacunae per unit area for the loaded limbs was 85 % and 60 % higher than for the non-loaded controls for the LSV and the HSC group, respectively (Figure 4). The number of infiltrated lacunae per unit area for the loaded and the non-loaded limbs from the LSV group was not significantly different than for the ipsilateral limbs from the HSC group.

Figure 4.

Tracer infiltration was enhanced in response to both LSV and HSC. No. of infiltrated lacunae per unit area (mm2) in loaded limb was higher than the non-loaded limb in response to both LSV and HSC (A). Quadrant-wise changes in infiltrated lacunae per unit area in case of low-strain vibration (B) and in case of high-strain compression (C) show that the infiltration is significantly enhanced in medial and lateral quadrant. No significant difference in overall or quadrant-wise infiltration between the ipsilateral limbs was observed.

*: significantly different from contralateral limb as determined by paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Tracer infiltration in the medial quadrant was enhanced significantly in response to both LSV and HSC. Infiltration also increased significantly in the lateral quadrant in response to LSV (Figure 4). In the medial and lateral quadrant of the LSV group, the no. of infiltrated lacunae per unit area for the loaded limb was 90 % and 160 % greater, respectively, than the corresponding quadrants of the non-loaded limb. The number of infiltrated lacunae per unit area in the medial quadrant of the loaded limb of HSC group was 70 % greater than the corresponding quadrant of the non-loaded limb. There was no significant difference in infiltration between the ipsilateral limbs of the LSV and the HSC group for any of the quadrants.

Gene Expression

Low-strain vibration

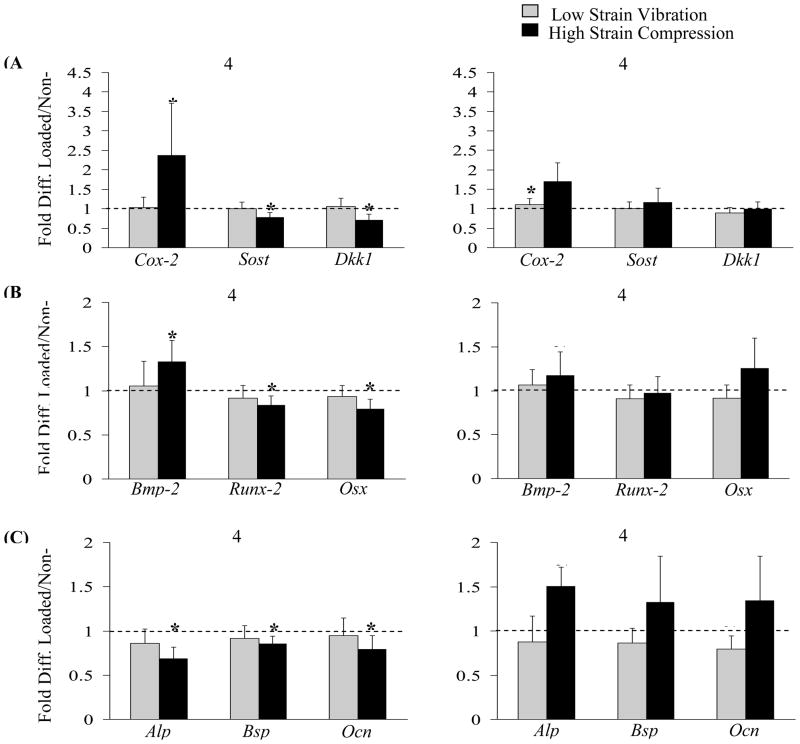

Gene expression levels, with the exception of Cox-2 and Ocn, did not differ between the loaded and non-loaded tibias at both the 4-hour and 4-day time points (Figure 5). At day 4 the loaded limb had significantly higher expression of Cox-2 compared to non-loaded limb however the fold change was merely 1.09. We also observed a trend (p<0.075) towards down-regulation of the expression level of Ocn (0.79 fold) by day 4.

Figure 5.

LSV led to little changes in expression level of mechano-responsive (A), differentiation related genes (B) and mineralization related genes (C) at either 4-hour or 4-day time point. The gene expression data is presented as fold difference (mean ±sd) between the loaded and non-loaded tibia. Up-regulation of mechano-responsive gene Cox-2 and down regulation of Wnt/Lrp pathway related genes Sost and Dkk1 at 4 hr in response to HSC supports its anabolic nature.

*: p<0.05, ~: p<0.075 significantly up-regulated or down regulated compared to expression level in non-loaded contralateral control.

High-Strain Compression

Gene expression levels of loaded tibias were significantly different than the non-loaded tibias at the 4-hour time point (Figure 5). However, only Alp and Bmp-2 showed a trend towards up-regulation at the 4-day time point. Cox-2 was up-regulated to 2.4 fold at 4-hour time point. Wnt/Lrp related genes, Sost and Dkk1, were down-regulated to 0.77 fold and 0.70 fold at 4-hour time point but the expression levels were normal at the 4-day time point. The osteoblast differentiation related genes Runx-2 and Osx were significantly down regulated (0.86 fold and 0.82 fold) while Bmp-2 was significantly up-regulated (1.33 fold) at the 4-hour time point. The mineralization related genes were also down regulated: Alp (0.69 fold), Bsp (0.85 fold) and Ocn (0.79) at the 4-hour time point.

Discussion

We studied the tissue and molecular level response of adult cortical bone subjected to low-strain vibration (LSV) and compared it with the response of bone subjected to a known anabolic stimulus: high-strain compression (HSC). We found that 5 days of daily LSV does not stimulate bone formation as indicated by dynamic histomorphometeric indices. In contrast we confirmed that 5 days of daily HSC stimulates a significant increase in bone formation, which validates its use as a positive control in our study. Interestingly we observed that chemo-transport, indicated by tracer infiltration in the lacunar-cannalicular porosity of cortical bone, is enhanced by brief (5 min) exposure to both LSV and HSC. The increase in infiltration was observed to be localized to the medial and the lateral quadrants of the mid-diaphyseal cross section. However, LSV resulted in negligible changes in expression levels of mechano-responsive, osteoblast differentiation-related and mineralization-related genes. In contrast, HSC resulted in significant changes in genes expression levels at the 4-hour time point and some prominent trends at 4-day time points.

The observed inability of short-term LSV loading to stimulate cortical bone formation in adult mice is consistent with our previous finding in a 5-week study [8]. The anabolic potential of dynamic loading is known to be dependent on the strain magnitude, the frequency of loading and the no. of loading cycles [29]. Empirical relationships, for instance the daily stress stimulus theory of bone adaptation, have been proposed to describe this dependence [6, 30]. It has been suggested that the strain magnitude required to maintain the bone mass decreases with increasing loading frequency and number of loading cycles [1]. One of the possible reasons for the non-anabolic nature of LSV could be a non-optimal combination of engendered strain and number of loading cycles, i.e. a strain level too low for the given number of loading cycles, or too few loading cycles for the given strain. For the given number of daily loading cycles applied in this study (N=63,000), the strain imparted by the LSV is higher than that estimated to maintain bone mass [6], however, it was not sufficient to stimulate bone formation. Recently, using a cantilever loading model of the mouse tibia, LaMothe et. al [31] observed increased cortical bone formation in response to 3 weeks of high-frequency loading (30 Hz, 800 με, 100 s daily, 5 days/week). However, the difference between strain engendered by loading and that required to maintain bone mass (estimated from the daily stress stimulus theory) in their study was higher than in our study (~250 με compared to ~150 με) whereas the age of the animals was lower (4 months old compared to 6–7 months old). If the strain threshold required to stimulate bone formation increases with age [32], it can be argued that the strain imparted by LSV was less than the threshold required to stimulate bone formation.

We would like to reiterate an important difference between bone adaptation in response to high-frequency, LMMS as considered in this study (LSV) and as reported by studies that employ WBV [2, 4]. In most of the WBV studies the strain imparted at the mid-diaphysis by the applied stimulus has been on the order of 10 με. Considering the number of cycles of dynamic loading, this strain value is lower than that required to maintain cortical bone mass as predicted by the daily stress stimulus theory [6]. Thus it is to be expected that such loading would not stimulate cortical bone formation. On the other hand, for the number of dynamic loading cycles used in our study, the strain imparted (~300 με) at mid-diaphysis is much higher than that required to maintain bone mass as predicted by daily stress stimulus theory. Hence the loading had a potential to trigger an anabolic bone adaptation at mid-diaphysis. Indeed LaMothe et al have set a precedent by demonstrating that bone formation at the mid-diaphysis can be stimulated with high-frequency loading that imparts mid-diaphyseal strain lower than the strain required to stimulate bone formation using low-frequency loading [31]. It should also be noted that the LSV loading modality allows one to measure and control the strain at the skeletal site where the response to applied loading is assessed. Thus the loading modality should find utility in understanding the structural and molecular level changes underlying bone adaptation. On the contrary, the anabolic changes in response to WBV have been mainly restricted to metaphyseal and epiphyseal trabecular bone, skeletal sites at which the in vivo strain engendered by the loading (WBV) cannot be controlled or measured. Therefore, although WBV might prove beneficial in treating osteoporosis, its use as a model to study the mechanisms underlying the high-frequency LMMS-related bone adaptation is limited.

The medial and the lateral quadrant of the cross section experiences maximum strain (tension and compression, respectively) under the axial loading modality considered in this study [7]. Therefore, an increase in tracer infiltration in these two quadrants of the loaded limb confirms the influence of loading on chemo-transport as proposed by Piekarski and Munro [33]. Changes in tracer infiltration in response to high-strain loading have also been reported by other studies [15, 16]. Similar to our observations, increased tracer infiltration in areas corresponding to medial and lateral quadrant (areas that experience high strain) was observed by Knothe Tate in a four-point bending model of the rat tibia [15]. Although theoretical models have been developed to predict transport in an idealized lacunar-cannalicular network [13], to our knowledge this is the first experimental study to report tracer infiltration in a bone subjected to high-frequency loading. The increased chemo-transport in response to LSV suggests that the solute exchange to and from osteocytes is enhanced and that in turn would result in increased viability of these cells. Since osteocyte apopotosis is linked with unloading related bone loss [34], such an increase in chemo-transport could be a possible explanation for the observed potential of low-strain high-frequency loading to inhibit disuse related bone loss.

Although tracer infiltration was enhanced in response to both LSV and HSC, bone formation occurred only in response to HSC, suggesting that chemo-transport is necessary but not sufficient to stimulate bone formation. It is possible that along with increased chemo-transport, higher magnitude variations in hydrostatic pressure and greater cyclic stretch associated with HSC provides the biophysical environment/signals necessary to stimulate bone formation. It should also be noted that tracer infiltration is not indicative of interstitial fluid flow magnitude and/or profile. It is possible for two different flow patterns to result in similar tracer infiltration, for instance a low-magnitude unidirectional flow might lead to similar infiltration as a high-magnitude oscillatory flow. If such differences exist between LSV and HSC, then the resulting shear stress generated at the osteocyte cell surface might be one of the possible reasons for observed differences in the ability of LSV and HSC to stimulate bone formation. Indeed differences in expression level of mechano-responsive gene Cox-2 in cultured osteocyte-like cells exposed to unidirectional versus oscillating flow have been shown before [35 ].

The non-anabolic nature of LSV is also reflected in few observed changes in expression of mechano-sensitive genes. While Cox-2 expression is upregulated in response to HSC at 4 hr, the expression level stays unchanged in the case of LSV. The importance of Cox-2 in mediating mechanical strain induced bone formation has been clearly demonstrated in previous studies. Using a four-point bending model of rat tibia, Forwood showed that inhibition of Cox-2 expression prior to loading completely blocked endo-cortical bone formation [18]. The decrease in expression level of Sost and Dkk1 in response to HSC but not LSV at the 4-hr time also indicates anabolic potential of one but not the other. Down-regulation of these Wnt/Lrp5 signaling related genes in response to axial compression of mouse ulna was also reported by Robling et. al.[20]. Also in case of HSC loading, the expression level of these two genes returns to normal at the 4-day time point suggesting the possibility of cellular accommodation to the applied loading [30].

Down-regulation in expression levels of osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization related genes in response to HSC at 4 hr time point might be the result of phenotype suppression indicating that an immediate response to loading is activation/proliferation of osteoblasts [36]. Similar decrease in expression levels of Alp, Ocn and Opn was reported in response to four-point bending of rat tibia, 4 hours post loading [17]. However, we observed that the expression levels of these genes show a trend towards up-regulation (Alp: p=0.057 and Bmp2: p=0.058) by day 4 implying the presence of mature osteoblast and/or matrix mineralization in response to HSC; this interpretation is also supported by dynamic histomorphometry results. Similar changes in Alp, Bsp and Ocn expression in mouse tibia subjected to four-point bending for 4 consecutive days were reported by Kesavan et. al [19]. The lack of phenotypic suppression at 4 hr time point or increased expression of differentiation and mineralization related genes at the 4-day time point in response to LSV further establishes its inability to stimulate bone formation.

One of the limitations of this study is that we did not follow the temporal changes in the bone structure in response to the loading stimuli and hence we cannot confirm or comment on the experimental handling related systemic bone loss, as observed in the 5 week study [8]. Nonetheless, HSC was able to overcome any such possible loss and trigger a local bone formation response while LSV did not. Another limitation is that the changes in expression levels of genes might be muted due to dilution as a result of inclusion of central 60–75% of tibia for RNA extraction in order to obtain sufficient amount of RNA for real-time RT-PCR. We anticipate higher fold changes if RNA were to be extracted from the central 5–10% of tibia; the region that experiences strain levels close to that measured using strain gauge. Also the bone marrow was not excluded prior to RNA extraction as we wanted to include the contribution of mesenchymal stem cells in gene expression changes associated with external loading. Analysis of gene expression from the bone and the marrow compartment separately could be considered in the future.

In summary, short-term low-strain vibration does not stimulate cortical bone formation, whereas high-strain compression does. We observed that tracer infiltration was enhanced in response to both loading stimuli and that the increase in infiltration was specific to medial and lateral quadrants of the mid-diaphyseal cross section, where engendered strains are greatest. However, negligible changes in expression level of mechano-responsive, osteoblast differentiation related and mineralization related genes were observed in tibia subjected to LSV. We conclude that low-strain vibration results in increased chemo-transport, but that this is not sufficient to stimulate cortical bone formation in adult mice.

Research Highlights.

Chemo-transport in cortical bone is enhanced in response to low-strain vibration.

Osteogenic gene expression does not change in response to low-strain vibration.

Cortical bone formation is not stimulated in response to low-strain vibration.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NIAMS grants R01AR047867, R21AR054371 and P30AR057235 (Washington University Center for Musculoskeletal Research). The protocol used to study tracer transport was provided to us by Dr. Susannah P. Fritton.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ozcivici E, Luu YK, Adler B, Qin X-Y, Rubin J, Judex S, Rubin CT. Mechanical signals as anabolic agents in bone. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:50–59. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin CT, Turner SA, Bain S, Mallinckrodt C, McLeod K. Anabolism: Low mechanical signals strengthen long bones. Nature. 2001;412:603–604. doi: 10.1038/35088122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garman R, Gaudette G, Donahue LR, Rubin C, Judex S. Low-level accelerations applied in the absence of weight bearing can enhance trabecular bone formation. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:732–740. doi: 10.1002/jor.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie L, Rubin C, Judex S. Enhancement of the adolescent murine musculoskeletal system using low-level mechanical vibrations. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1056–1062. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00764.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Judex S, Zhong N, Squire ME, Ye K, Donahue LR, Hadjiargyrou M, Rubin CT. Mechanical modulation of molecular signals which regulate anabolic and catabolic activity in bone tissue. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:982–94. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin Y-X, Rubin CT, McLeod KJ. Nonlinear dependence of loading intensity and cycle number in maintenance of bone mass and morphology. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:482–489. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christiansen BA, Bayly PV, Silva MJ. Constrained tibial vibration in mice: a method for studying the effects of vibrational loading of bone. J Biomech Eng. 2008;130:502–512. doi: 10.1115/1.2917435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christiansen BA, Kotiya AA, Silva MJ. Constrained tibial vibration does not producean anabolic bone response in adult mice. Bone. 2009;45:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowin SC, Moss-Salentijn L, Moss ML. Candidates for the mechanosensory system in bone. J Biomech Eng. 1991;113:191–197. doi: 10.1115/1.2891234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinbaum S, Cowin SC, Zeng Y. A model for excitation of osteocytes by mechanical loading-induced bone fluid shear stress. J Biomech. 1994;27:339–360. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knothe Tate ML. “Wither flows the fluid in bone?” An osteocyte’s perspective. Journal of Biomechanics. 2003;36:1409–1424. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritton SP, Weinbaum S. Fluid and solute transport in bone: Flow-induced mechanotransduction. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2009;41:347–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fluid.010908.165136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Cowin SC, Weinbaum S, Fritton SP. Modeling tracer transport in an osteon under cyclic loading. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000;28:1200–1209. doi: 10.1114/1.1317531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens HY, Meays DR, Frangos JA. Pressure gradients and transport in the murine femur upon hindlimb suspension. Bone. 2006;39:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knothe Tate ML, Steck R, Forwood MR, Niederer P. In vivo demonstration of load-induced fluid flow in the rat tibia and its potential implications for processes associated with functional adaptation. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:2737–2745. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.18.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tami AE, Schaffler MB, Knothe Tate ML. Probing the tissue to subcellular level structure underlying bone’s molecular sieving function. Biorheology. 2003;40:577–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raab-Cullen DM, Thiede MA, Petersen DN, Kimmel DB, Recker RR. Mechanical loading stimulates rapid changes in periosteal gene expression. Calcif Tissue Int. 1994;55:473–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00298562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forwood MR. Inducible cyclo-oxygenase (COX-2) mediates the induction of bone formation by mechanical loading in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1688–1693. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesavan C, Mohan S, Oberholtzer S, Wergedal JE, Baylink DJ. Mechanical loading-induced gene expression and BMD changes are different in two inbred mouse strains. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1951–1957. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00401.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robling AG, Niziolek PJ, Baldridge LA, Condon KW, Allen MR, et al. Mechanical stimulation of bone in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of sost/sclerostin. J Bio Chem. 2008;283:5866–5875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonewald LF, Johnson ML. Osteocytes, mechanosensing and Wnt signaling. Bone. 2008;42:606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.12.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Souza RL, Matsuura M, Eckstein F, Rawlinson SCF, Lanyon LE, Pitsillides AA. Non-invasive axial loading of mouse tibiae increases cortical bone formation and modifies trabecular organization: A new model to study cortical and cancellous compartments in a single loaded element. Bone. 2005;37:810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiyama T, Price JS, Lanyon LE. Functional adaptation to mechanical loading in both cortical and cancellous bone is controlled locally and is confined to the loaded bones. Bone. 2010;46:314–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2:595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Ciani C, Doty SB, Fritton SP. Delineating bone’s interstitial fluid pathway in vivo. Bone. 2004 Mar;34:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bardelmeijer HA, Buckle T, Ouwehand M, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM, Van Tellingen O. Cannulation of the jugular vein in mice: a method for serial withdrawal of blood samples. Laboratory Animals Ltd Laboratory Animals. 2003;37:181–187. doi: 10.1258/002367703766453010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wohl GR, Towler DA, Silva MJ. Stress fracture healing: fatigue loading of the rat ulna induces upregulation in expression of osteogenic and angiogenic genes that mimic the intramembranous portion of fracture repair. Bone. 2009;44:320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warden SJ, Turner CH. Mechanotransduction in cortical bone is most efficient at loading frequencies of 5–10 Hz. Bone. 2004;34:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner CH. Three rules for bone adaptation to mechanical stimuli. Bone. 1998;23:399–407. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaMothe JM, Zernicke RF. Rest insertion combined with high-frequency loading enhances osteogenesis. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1788–1793. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01145.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner CH, Takano Y, Owan I. Aging changes mechanical loading thresholds for bone formation in rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1544–1549. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piekarski K, Munro M. Transport mechanism operating between blood supply and osteocytes in long bones. Nature. 1977;269:80–82. doi: 10.1038/269080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aguirre JI, Plotkin LI, Stewart SA, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Osteocyte apoptosis is induced by weightlessness in mice and precedes osteoclast recruitment and bone loss. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:605–15. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponik SM, Triplett JW, Pavalko FM. Osteoblasts and osteocytes respond differently to oscillatory and unidirectional fluid flow profiles. J Cell Biochem. 2007;15(100):794–807. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lian JB, Stein GS, Bortell R, Owen TA. Phenotype suppression: a postulated molecular mechanism for mediating the relationship of proliferation and differentiation by Fos/Jun interactions at AP-1 sites in steroid responsive promoter elements of tissue-specific genes. J Cell Biochem. 1991;45:9–14. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240450106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]