Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

To validate the reported association between rs10494366 in NOS1AP (the gene encoding nitric oxide synthase-1 adaptor protein) and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in calcium channel blocker (CCB) users and to identify additional NOS1AP variants associated with type 2 diabetes risk.

Methods

Data from 9 years of follow-up in 9,221 middle-aged white and 2,724 African-American adults free of diabetes at baseline from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study were analysed. Nineteen NOS1AP variants were examined for associations with incident diabetes and fasting glucose levels stratified by baseline CCB use.

Results

Prevalence of CCB use at baseline was 2.7% (n= 247) in whites and 2.3% (n=72) in African-Americans. Among white CCB users, the G allele of rs10494366 was associated with lower diabetes incidence (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.35–0.92, p=0.016). The association was marginally significant after adjusting for age, sex, obesity, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, hypertension, heart rate and electrocardiographic QT interval (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.38–1.04, p=0.052). rs10494366 was associated with lower average fasting glucose during follow-up (p=0.037). No other variants were associated with diabetes risk in CCB users after multiple-testing correction. No associations were observed between any NOS1AP variant and diabetes development in non-CCB users. NOS1AP variants were not associated with diabetes risk in either African-American CCB users or non-CCB users.

Conclusions/interpretation

We have independently replicated the association between rs10494366 in NOS1AP and incident diabetes among white CCB users. Further exploration of NOS1AP variants and type 2 diabetes and functional studies of NOS1AP in type 2 diabetes pathology is warranted.

Keywords: ARIC study, Calcium channel blockers, Gene–drug interaction, NOS1AP, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Initial identification of NOS1AP (the gene encoding nitric oxide synthase-1 adaptor protein [NOS1AP]) as a candidate for type 2 diabetes was generated from a strong linkage signal from the chromosome 1q21–q25 region from several studies [1, 2]. Subsequent linkage and association studies in seven populations confirmed that variants in NOS1AP are associated with diabetes in several different ethnic populations from the 1q Consortium [3–7]. NOS1AP lies directly under the linkage peak at 1q23 and is a strong biological candidate, with function related to nitric oxide (NO) synthesis and release [8]. Mice with mutations in proteins essential for NO synthesis exhibit insulin resistance [9, 10]. Experimental evidence of the effect of NO on glucose metabolism in humans is not available yet; however, results from observational studies suggest lowered NO availability in those with type 2 diabetes [11]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in NOS1AP have also been associated with cardiac repolarisation in humans, as assessed through the electrocardiographic QT interval [12] and risk of sudden cardiac death [13]. However, the mechanism through which NOS1AP acts on myocytes is currently unknown, but it is believed to interact with NO synthase-1 to regulate intracellular calcium [14, 15].

Recently, Becker et al. [16] reported an association of rs10494366 in NOS1AP with incident type 2 diabetes among calcium channel blocker (CCB) users in the Rotterdam study (HR for GG and GT vs TT 0.56, 95% CI 0.33–0.97). CCBs are a class of medication used to treat hypertension, angina and certain arrhythmias. Since rs10494366 has been shown to be associated with cardiac repolarisation [12], it is hypothesised that either rs10494366 or another SNP in linkage disequilibrium with it may influence calcium handling through voltage-gated calcium channels, which are blocked by CCB. Thus, rs10494366 may influence insulin secretion and be associated with type 2 diabetes risk in CCB users. The goals of this investigation are twofold: (1) to replicate the association results of rs10494366 and type 2 diabetes incidence, and (2) identify other variants in NOS1AP associated with development of type 2 diabetes, among CCB users from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

Methods

Study population and data assessment

The ARIC study is a longitudinal population-based observational study initiated in 1987 to investigate the natural history of clinical and subclinical atherosclerosis [17]. Total enrolment from four US cities consisted of 15,792 middle-aged participants (11,478 whites, 4,266 African-Americans). Individuals were examined at baseline and re-examined three times at 3 year intervals. Average retention rate over the 9 year follow-up was 93%. Those white participants who did not consent to genetic research (n=113), had diabetes at baseline (n=1,060) or had <75% of genotypes called (n=642) [13] were excluded from this analysis. Those African-American participants who did not consent to genetic research (n=23), had diabetes at baseline (n=940) or had <75% of genotypes called (n=401) were excluded from analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from patients when appropriate. Procedures were followed in accordance with ethical standards of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Office of Human Subjects Research and Institutional Review Board.

At each visit, diabetes status was determined by self-report of diabetes diagnosis, use of diabetes medications, fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l, or non-fasting glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l. Use of hypertension medication (including CCBs) was assessed at baseline and at each subsequent follow-up visit. Participants were asked to bring all prescription and non-prescription medications that had been taken in the past 2 weeks and these were recorded. Hypertension medications were defined as medications with pharmacological evidence of lowering BP.

Age, sex, BMI, BP, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, QT interval and heart rate were all obtained during the baseline visit. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥140 mmHg, diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg or self-reported use of hypertension medication. The Baecke Physical Activity questionnaire was used to derive leisure-time physical activity measures; activity indices range from a low of 1 (least active) to a high of 5 (most active) [18, 19]. Three levels of alcohol status and smoking status were established: never, former, current. At all visits serum glucose was measured by a standard hexokinase method on a Coulter DACOS (Coulter Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA).

SNP selection and genotyping

SNPs were selected to tag the linkage disequilibrium block containing rs10494366 and rs4657139 (the most significant SNPs from fine mapping of QT interval from a previous study in whites [12, 13]). Twenty-one SNPs were selected using Tagger [20, 21] with criteria of r2>0.65 and minor allele frequency (MAF)>0.05 in a population with western European ancestry. Genotyping was performed on Open Array SNP genotyping from Biotrove [22], a Taqman-based multiplex system. rs12567211 and rs1572495 were dropped because of poor genotyping quality. Out of the remaining SNPs, rs12026452, rs4657139 and rs4657154 were not in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p<0.01).

Statistical analysis

Nineteen NOS1AP variants were examined in association with incident type 2 diabetes using Cox proportional hazards regression. Diabetes incidence date was estimated by using linear interpolation of glucose values at the visit at which diabetes was diagnosed and the preceding visit, as described in Duncan et al. [23]. For those who did not return to the study or were administratively censored, follow-up time was determined as the last study visit date. An additive genetic model was assumed. Multivariable models were constructed adjusting for age, sex, hypertension, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, obesity, QT interval and heart rate.

A staggered-entry Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed using updated medication data from all visits. We included participants in the risk set at first use of CCB and censored participants when CCB was discontinued or if the participant was lost to follow-up. A total of 816 CCB users were included in this analysis.

Significance level for replication analyses of rs10494366 was set at α<0.05. The Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple comparisons in analyses of the other 18 SNPs; p<0.003 (=0.05/18) was considered significant. False-positive report probability (FPRP) was calculated using the worksheet of Wacholder et al. [24]; FPRP <0.20 is considered a noteworthy finding.

SNPs significantly associated with type 2 diabetes in univariate analyses were assessed for association with fasting glucose measures across all visits using generalised estimating equations (GEEs). In addition, we performed a multivariable GEE analysis adjusting for baseline age, sex, hypertension, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, obesity, QT interval and heart rate. Participants were censored from GEE analysis at the visit of incident diabetes or at last follow-up.

All analyses were stratified by race. R version 2.8 was used for all analyses (http://cran.r-project.org/).

Power calculations

For our SNP of interest, rs10494366, given the 247 white CCB users at baseline, observed G allele frequency of 35% in whites, a 17% probability of developing type 2 diabetes in CCB users and setting α=0.05, we have an estimated 64–88% power to detect univariate HRs between 0.5 and 0.6 in whites. Given the 72 African-American CCB users at baseline, an observed G allele frequency of 61% in African-Americans, 22% probability of developing type 2 diabetes in CCB users and setting α=0.05, we have an estimated 27–44% power to detect univariate HRs between 0.5 and 0.6 for African-Americans. Power calculations were performed using PASS 2008, version 08.0.10 [25].

Results

A total of 9,221 white participants were available for analysis after applying exclusion criteria and 10% (n=930) of these individuals developed incident diabetes over 9 years of follow-up. Among the 7,101 participants who were not taking hypertension medications, 8.2% (n=581) developed diabetes and the corresponding figures were 16.4% (307 of 1,873) in participants who used hypertension medications other than CCB and 17.0% (42 of 247) in CCB users (alone or in combination with other hypertension medications). Of those who reported using only CCB, 11.6% (13 of 112) developed diabetes and the corresponding figures were 16.4% (307 of 1,873) in those on hypertension medication other than CCB, and 21.5% (29 of 135) in those using CCB in combination with other hypertension medication. Population characteristics of 9,221 white ARIC study participants at baseline stratified by baseline CCB use can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 9,221 white ARIC study participants at baseline stratified by CCB use

| Characteristic | CCB users |

Non-CCB users |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n or mean | SD | % | n or mean | SD | % | |

| Total sample size (n) | 247 | – | 8,974 | – | ||

| Incident type 2 diabetes cases (n) | 42 | 17 | 888 | 9.9 | ||

| Age, years (mean) | 56.3 | 5.7 | 54.1 | 5.7 | ||

| Female (n) | 87 | 35 | 4,869 | 54 | ||

| Obese, ≥30 kg/m2 (n) | 59 | 24 | 1,806 | 20 | ||

| Physical activity index (mean) | 2.5 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 0.5 | ||

| QT interval, ms (mean) | 411.0 | 33.0 | 400.0 | 29.0 | ||

| Heart rate, beats per min (mean) | 64.2 | 10.2 | 65.7 | 9.6 | ||

| Hypertension (n) | 157 | 65 | 2,086 | 23a | ||

| Smoking (n) | ||||||

| Never | 83 | 34 | 3,656 | 41a | ||

| Former | 102 | 41 | 3,178 | 35 | ||

| Current | 62 | 25 | 2,135 | 24 | ||

| Alcohol drinking (n) | ||||||

| Never | 41 | 17 | 1,596 | 18a | ||

| Former | 65 | 26 | 1,405 | 16 | ||

| Current | 141 | 57 | 5,958 | 66 | ||

Percentages for non-CCB users for hypertension, smoking and alcohol drinking are based on the number participants with non-missing data. Number of non-CCB user participants with missing data were: hypertension, 41; smoking, 5; alcohol drinking, 15

After exclusions, 2,724 African-American participants were available for analysis. The population characteristics are available in Electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1. We had limited power for these analyses owing to the small number of individuals; however, we have provided results from univariate analyses for African-Americans in ESM Table 2. The rest of the results are derived from analyses in whites only.

Overall, there was no significant association between any of the 19 NOS1AP variants with type 2 diabetes (p values ranged from 0.015 to 0.955; ESM Table 3). Univariate analyses of NOS1AP variants stratified by CCB use are presented in Table 2. Among CCB users, rs10494366 was associated with lower incidence of type 2 diabetes (HR per additional copy of G allele 0.57, 95% CI 0.35–0.92, p= 0.016). There was no association of rs10494366 and development of diabetes in non-CCB users (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93–1.13, p=0.66; pinteraction=0.0128). None of the SNPs previously associated with QT interval [13] (rs12567209, rs4657139 and rs16847548) was associated with development of type 2 diabetes in CCB or non-CCB users after Bonferroni correction (Table 2). The most significant variant tested among white CCB users was rs7532690 (p=0.008); however, rs7532680 did not pass the a priori significance threshold set to correct for multiple testing. None of the remaining NOS1AP variants was associated with type 2 diabetes after Bonferroni correction (Table 2). The rs10494366 genotype was not associated with the use of CCB medications (p=0.99).

Table 2.

Alleles, MAFs, HRs, 95% CIs and p values of developing type 2 diabetes for NOS1AP variants in univariate and multivariate models

| Model/SNP | Major/minor | MAF | CCB users |

Non-CCB users |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |||

| Univariate | ||||||||

| rs12022536 | G/A | 0.18 | 0.61 | 0.32–1.16 | 0.11 | 1.09 | 0.97–1.23 | 0.14 |

| rs12026931 | T/C | 0.09 | 0.75 | 0.31–1.84 | 0.51 | 1.07 | 0.91–1.25 | 0.40 |

| rs7532680 | C/T | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.20–0.87 | 0.008 | 1.14 | 1.01–1.28 | 0.030 |

| rs4656345 | G/A | 0.04 | 0.92 | 0.30–2.87 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.76–1.23 | 0.80 |

| rs7514121 | A/G | 0.21 | 0.59 | 0.31–1.13 | 0.090 | 1.18 | 1.05–1.32 | 0.004 |

| rs885092 | G/A | 0.15 | 0.86 | 0.41–1.78 | 0.67 | 1.11 | 0.98–1.27 | 0.10 |

| rs7539281 | G/A | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0.26–0.88 | 0.011 | 1.13 | 1.01–1.25 | 0.028 |

| rs4657139a | T/A | 0.33 | 0.59 | 0.36–0.99 | 0.038 | 1.07 | 0.96–1.18 | 0.21 |

| rs16847548 | T/C | 0.22 | 0.66 | 0.37–1.17 | 0.13 | 1.04 | 0.93–1.16 | 0.53 |

| rs12567209 | G/A | 0.07 | 0.74 | 0.28–1.95 | 0.52 | 1.17 | 0.99–1.39 | 0.077 |

| rs1415262 | G/C | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.37–0.99 | 0.039 | 1.04 | 0.94–1.15 | 0.44 |

| rs10494366 | T/G | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.35–0.92 | 0.016 | 1.02 | 0.93–1.13 | 0.67 |

| rs16856785 | G/C | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.22–1.31 | 0.13 | 1.09 | 0.93–1.27 | 0.31 |

| rs4657154a | G/A | 0.27 | 0.70 | 0.42–1.17 | 0.16 | 1.01 | 0.91–1.12 | 0.89 |

| rs7540690 | G/A | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.50–1.41 | 0.50 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.15 | 0.69 |

| rs10918762 | A/G | 0.21 | 0.77 | 0.44–1.32 | 0.32 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.14 | 0.79 |

| rs12124105 | A/T | 0.06 | 1.42 | 0.63–3.22 | 0.42 | 1.05 | 0.87–1.27 | 0.61 |

| rs12068421 | C/T | 0.14 | 0.57 | 0.27–1.20 | 0.10 | 0.95 | 0.83–1.09 | 0.44 |

| rs12026452a | G/A | 0.15 | 0.91 | 0.49–1.71 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.81–1.07 | 0.29 |

| Multivariateb | ||||||||

| rs4657139a | 0.67 | 0.41–1.12 | 0.065 | 1.07 | 0.96–1.18 | 0.35 | ||

| rs16847548 | 0.71 | 0.40–1.26 | 0.11 | 1.04 | 0.93–1.16 | 0.63 | ||

| rs12567209 | 0.73 | 0.27–1.92 | 0.56 | 1.17 | 0.99–1.39 | 0.075 | ||

| rs10494366 | 0.63 | 0.38–1.04 | 0.052 | 1.03 | 0.93–1.14 | 0.70 | ||

An additive genetic model was assumed; the major allele is the reference allele

Genotypes not in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, p<0.01

Multivariate model adjusted for age, sex, obesity, hypertension, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, QT interval and heart rate

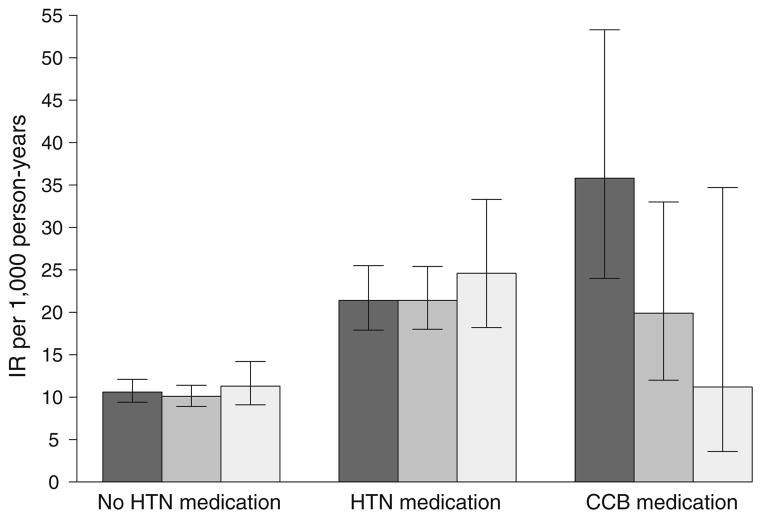

Figure 1 shows the effect of rs10494366 genotype on risk of type 2 diabetes by medication use as incidence rates (IRs) for non-users of hypertension medication (n=6,875), other hypertension (non-CCB) medication users (n=1,818) and CCB users (n=241). No differences in risk of type 2 diabetes among non-hypertension medication users or other hypertension medication users by rs10494366 genotype were observed (ptrend of IRs=0.89 and 0.49, respectively). However, among the CCB medication users, compared with CCB users with the TT genotype, those with the GT genotype were 44% less likely to develop type 2 diabetes (IRGT-CCB 19.9, 95% CI 12.0–33.0 vs IRTT-CCB 35.8, 95% CI 24.0–53.3, p=0.037) and those with the GG genotype were 68% less likely to develop type 2 diabetes (IRGG-CCB 11.2, 95% CI 3.6–34.7 vs IRTT-CCB 35.8, 95% CI 24.0–53.3, p=0.018). Among CCB users, each increasing G allele is associated with a decreased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, ptrend=0.026.

Fig. 1.

Type 2 diabetes IRs per 1,000 person-years (95% CIs) for the rs10494366 genotype, stratified by non-users of hypertension (HTN) medication, HTN medication (non-CCB) users and CCB users. Dark grey bars, TT genotype; medium grey bars, GT genotype; light grey bars, GG genotype. Non-HTN medication users, trend test, p=0.89; HTN medication (non-CCB users), trend test, p=0.49; CCB medication users, trend test, p=0.026

Multivariate analyses adjusting for age, sex, obesity, hypertension, physical activity, smoking status, drinking status, QT interval and heart rate for the four SNPs previously associated with cardiac repolarisation are presented in Table 2. Adjustment attenuated the association between rs10494366 and development of diabetes in CCB users (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.38–1.04, p=0.052), but was marginally significant. Adjusting for smoking and obesity attenuated the signal the most. Inclusion of QT interval did not significantly affect the association between rs10494366 and type 2 diabetes among CCB users. Therefore, QT interval was not an intermediate in our analysis.

Further analysis of rs10494366 showed the G allele was associated with lower average fasting glucose levels across all four follow-up visits (β-coefficient −0.082 mmol/l per G allele, p=0.037) among CCB users. Adjusting for baseline covariates diminished the association (β-coefficient −0.052 mmol/l per G allele, p=0.18) in CCB users. However, this attenuated association can be attributed to over adjustment, since glucose is most likely an intermediate in the causal pathway between rs10494366 and type 2 diabetes. No significant associations were observed in non-CCB users.

To determine how aggregating CCB users over follow-up may affect our results, we performed a staggered-entry analysis using updated prescription medication data from all visits. Participants entered the risk set at first reported use of CCB. Individuals were censored when CCB was discontinued or lost to follow-up. A total of 817 CCB users over follow-up were included in this Cox proportional analysis. rs10494366 was associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.49–0.99, p=0.036). None of the other NOS1AP variants was associated with risk of type 2 diabetes in time-dependent analyses after adjusting for multiple testing (data not shown).

It is possible that the association between NOS1AP and type 2 diabetes involves mechanisms associated with medications affecting calcium signalling in general, such as beta blockers. However, we found no association between rs10494366 with type 2 diabetes in beta-blocker users overall or in subclasses of beta blockers (data not shown). It is also possible that NOS1AP is interacting with some other factor of which CCB use is an indicator. Therefore we performed analyses stratified by covariates that are associated with both CCB use and type 2 diabetes (age >60 years, sex and hypertension status). No association was found between rs10494366 and risk of diabetes in any of the stratified subgroups (data not shown). We did not find an association between rs10494366 genotype and mortality overall (p=0.55), nor among CCB users (p= 0.64) or non-CCB users (p=0.47).

Discussion

We have validated a previously reported association between rs10494366 of NOS1AP and decreased risk of type 2 diabetes in an independent sample of CCB users in the population-based ARIC study. Additionally, we present evidence of an association between rs10494366 and lower average fasting glucose during follow-up among white CCB users.

As with all genetic association studies there is the possibility of false-positive association caused by type I error. We examined this problem by calculating the FPRP for rs10494366 using Wacholder’s spreadsheet [24]. FPRP ranged from 0.10 to 0.25 assuming an HR of 1.7 and high prior probabilities, indicating a low probability that this finding is a false positive. FPRP calculation for other SNPs did not pass the 0.20 threshold.

The initial study that identified the association between rs10494366 and type 2 diabetes among CCB users reported an HR of 0.56 (95% CI 0.33–0.97) for a dominant genetic model [16]. A meta-analysis of the reported effect sizes from both the Rotterdam and ARIC Studies (HRDOMINANT 0.50, 95% CI 0.27–0.93) reveals a combined HR of 0.53 (95% CI 0.36–0.80) for development of type 2 diabetes comparing the GG and GT genotypes of rs10494366 with the TT genotype in CCB users. For those reasons we believe the decreased risk of type 2 diabetes for carriers of the G allele of rs10494366 in CCB users is not a false positive, despite small numbers of baseline CCB users.

Several limitations of this study warrant discussion. First, we were limited by the small number of white CCB users at baseline (n=247). However, the number of CCB users who developed type 2 diabetes in this study is similar to the number of cases in the study conducted by Becker et al. [16] (n=42 and 55, respectively), even though Becker et al. reported a larger number of CCB users (n=816). Second, our genotyping coverage of NOS1AP was not comprehensive. In the ARIC study, this region of NOS1AP was primarily genotyped to detect an association with QT interval in whites. Genotyping was focused on the 5′ end of the gene where previous studies had observed an association with QT interval [12]. We were not able to perform additional genotyping in NOS1AP. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of other associations in NOS1AP. Third, our power to analyse the association between NOS1AP variants and type 2 diabetes in African-American ARIC study participants was very limited and the analyses were considered exploratory. But, since the ARIC study is one of the few datasets with African-American participants and substantial medication data and we feel the results could inform future studies in African-Americans, we presented basic univariate analyses in African-American CCB users in the ESM. Finally, we were not able to stratify by class of CCB and examine the effect of dihydropyridines and non-dihydropyridines; medication data collected by the ARIC study were not inclusive of CCB type.

Nevertheless, our study has several strengths. The ARIC study is a well-characterised cohort with high response rates from its participants and well-validated data. We were able to capture incident type 2 diabetes cases and examine the role of NOS1AP polymorphisms in development of type 2 diabetes. Additionally, the availability of continuous intermediate phenotypes allowed us to explore potential mechanisms through which variants of NOS1AP might affect diabetes development.

There are currently no published functional studies investigating variable expression of NOS1AP polymorphisms. Thus, the role of NOS1AP in the pancreatic beta cell and development of type 2 diabetes has yet to be elucidated. But evidence from electrophysiological studies of NOS1AP in ventricular myocytes [26], which share some signalling characteristics with the beta cell, suggests a diabetogenic mechanism; NOS1AP interferes with voltage-dependent calcium channels, thus affecting calcium handling in the myocytes (and potentially, the beta cell).

If the mechanism of NOS1AP is confirmed, prescription of CCBs could affect risk of type 2 diabetes differentially by genotypes of NOS1AP variants. Future studies, especially experimental trials of CCB, should attempt to replicate our findings and identify functional SNPs in NOS1AP associated with type 2 diabetes. Functional molecular studies are needed to determine the biological mechanism(s) that link NOS1AP to type 2 diabetes in the presence of CCBs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The ARIC study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HC-55015, N01-HC-55016, N01-HC-55018, N01-HC-55019, N01-HC-55020, N01-HC-55021 and N01-HC-55022. A. Y. Chu was supported by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases training grant (T32-DK62707) and by a National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute training grant (T32-HL007024). Findings were previously published in abstract form at the 69th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–9 June 2009. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Abbreviations

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- CCB

Calcium channel blocker

- FPRP

False-positive report probability

- GEE

Generalised estimating equation

- IR

Incidence rate

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOS1AP

Nitric oxide synthase-1 adaptor protein

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

Duality of interest The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1608-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Contributor Information

A. Y. Chu, Email: achu@jhsph.edu, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA. 615 N. Wolfe Street, Suite W6513, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA

J. Coresh, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

D. E. Arking, Nathan McKusick Institute of Genomic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

J. S. Pankow, Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN, USA

G. F. Tomaselli, Department of Cardiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

A. Chakravarti, Nathan McKusick Institute of Genomic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

W. S. Post, Department of Cardiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

P. H. Spooner, Department of Cardiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

E. Boerwinkle, Health Science Center, University of Texas, Houston, TX, USA

W. H. L. Kao, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

References

- 1.Elbein SC, Hoffman MD, Teng K, Leppert MF, Hasstedt SJ. A genome-wide search for type 2 diabetes susceptibility genes in Utah Caucasians. Diabetes. 1999;48:1175–1182. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson RL, Ehm MG, Pettitt DJ, et al. An autosomal genomic scan for loci linked to type II diabetes mellitus and body-mass index in Pima Indians. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1130–1138. doi: 10.1086/302061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langefeld CD, Wagenknecht LE, Rotter JI, et al. Linkage of the metabolic syndrome to 1q23–q31 in Hispanic families: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study Family Study. Diabetes. 2004;53:1170–1174. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng MC, So WY, Lam VK, et al. Genome-wide scan for metabolic syndrome and related quantitative traits in Hong Kong Chinese and confirmation of a susceptibility locus on chromosome 1q21–q25. Diabetes. 2004;53:2676–2683. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das SK, Hasstedt SJ, Zhang Z, Elbein SC. Linkage and association mapping of a chromosome 1q21–q24 type 2 diabetes susceptibility locus in northern European Caucasians. Diabetes. 2004;53:492–499. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsueh WC, St Jean PL, Mitchell BD, et al. Genome-wide and fine-mapping linkage studies of type 2 diabetes and glucose traits in the Old Order Amish: evidence for a new diabetes locus on chromosome 14q11 and confirmation of a locus on chromosome 1q21–q24. Diabetes. 2003;52:550–557. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prokopenko I, Zeggini E, Hanson RL, et al. Linkage disequilibrium mapping of the replicated type 2 diabetes linkage signal on chromosome 1q. Diabetes. 2009;58:1704–1709. doi: 10.2337/db09-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffrey SR, Snowman AM, Eliasson MJ, Cohen NA, Snyder SH. CAPON: a protein associated with neuronal nitric oxide synthase that regulates its interactions with PSD95. Neuron. 1998;20:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duplain H, Burcelin R, Sartori C, et al. Insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2001;104:342–345. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shankar RR, Wu Y, Shen HQ, Zhu JS, Baron AD. Mice with gene disruption of both endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthase exhibit insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2000;49:684–687. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashyap SR, Roman LJ, Lamont J, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with impaired nitric oxide synthase activity in skeletal muscle of type 2 diabetic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1100–1105. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arking DE, Pfeufer A, Post W, et al. A common genetic variant in the NOS1 regulator NOS1AP modulates cardiac repolarization. Nat Genet. 2006;38:644–651. doi: 10.1038/ng1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao WH, Arking DE, Post W, et al. Genetic variations in nitric oxide synthase 1 adaptor protein are associated with sudden cardiac death in US white community-based populations. Circulation. 2009;119:940–951. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonoudakis D, Mailliard W, Wingerd K, Clegg D, Vandenberg C. Inward rectifier potassium channel Kir2.2 is associated with synapse-associated protein SAP97. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:987–998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.5.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim E, Sheng M. Differential K+ channel clustering activity of PSD-95 and SAP97, two related membrane-associated putative guanylate kinases. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker ML, Visser LE, Newton-Cheh C, et al. Genetic variation in the NOS1AP gene is associated with the incidence of diabetes mellitus in users of calcium channel blockers. Diabetologia. 2008;51:2138–2140. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folsom AR, Arnett DK, Hutchinson RG, Liao F, Clegg LX, Cooper LS. Physical activity and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged women and men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:901–909. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199707000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:936–942. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe’er I, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/ng1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Bakker PI. Tagger: Selection and evaluation of tag SNPs. [accessed 30 October 2009];2005 doi: 10.1101/pdb.ip67. Available from www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/tagger/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Biotrove Life sciences solutions. [accessed 30 October 2009]; Available from http://biotrove.com/

- 23.Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Pankow JS, et al. Low-grade systemic inflammation and the development of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes. 2003;52:1799–1805. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wacholder S, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, El Ghormli L, Rothman N. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:434–442. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hintze J. PASS 2008: Power analysis and sample size calculator. [accessed 30 October 2009];2008 Available from www.ncss.com/pass.html.

- 26.Chang KC, Barth AS, Sasano T, et al. CAPON modulates cardiac repolarization via neuronal nitric oxide synthase signaling in the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4477–4482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709118105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.