Summary

Synaptotagmin 1 (syt1) functions as the Ca2+-sensor for neuronal exocytosis. Here site-directed spin labeling was used to examine the complex formed between a soluble fragment of syt1, which contains its two C2 domains, and the neuronal core SNARE complex. Changes in EPR lineshape and accessibility for spin-labeled syt1 mutants indicate that in solution, the assembled core SNARE complex contacts syt1 in several regions. For the C2B domain, contact occurs in the polybasic face and sites opposite the Ca2+-binding loops. For the C2A domain, contact is seen with the SNARE complex in a region near loop 2. Double electron-electron resonance was used to estimate distances between the two C2 domains of syt1. These distances have broad distributions in solution, which do not significantly change when syt1 is fully associated with the core SNARE complex. The broad distance distributions indicate that syt1 is structurally heterogeneous when bound to the SNAREs and does not assume a well-defined structure. Simulated annealing using EPR-derived distance restraints produces a family of syt1 structures where the Ca2+-binding regions of each domain face in roughly opposite directions. The results suggest that when associated with the SNAREs, syt1 is configured to bind opposing bilayers, but that the syt1/SNARE complex samples multiple conformational states.

Keywords: Site-directed spin labeling, EPR spectroscopy, membrane fusion, protein-protein interactions, calcium-binding protein

Introduction

In the central nervous system, the release of neurotransmitter occurs through a highly-regulated Ca2+-dependent membrane fusion event that releases the contents of the synaptic vesicle into the synaptic cleft. Although a large number of proteins act to facilitate this fusion process, the SNARE proteins (soluble NSF (N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor) attachment protein receptors) are thought to make up the core of the fusion machinery. The SNAREs include plasma membrane associated syntaxin, vesicle associated synaptobrevin and SNAP-25 1, and they form a 4-helix bundle that acts to drive the vesicle and plasma membranes together 2; 3. However, the SNAREs are not directly responsible for sensing Ca2+, and in neuronal exocytosis there is compelling evidence that synaptotagmin 1 (syt1) functions as the Ca2+-sensor and is responsible for the fast synchronous release of neurotransmitter 4; 5; 6.

Synaptotagmin 1 is one of several proteins, including the complexins, Munc18 and CAPS, which regulate fusion and or the assembly of the SNARE complex. At the present time, the mechanisms and points at which these proteins function are not precisely known. Synaptotagmin 1 binds and penetrates membranes in a Ca2+-dependent manner 7; 8, and it has been observed to bind the assembled SNARE complex 5; 9 as well as the individual SNARE proteins syntaxin and SNAP-25 10; 11; 12. A current popular view in the field is that fusion is controlled by SNARE zippering 1, which is generally believed to proceed from the N-terminal to the C-terminal membrane anchors of syntaxin and synaptobrevin, ultimately forming a close junction between opposing membranes. However, it is not known whether syt1 acts to regulate and facilitate SNARE assembly, or whether it acts on the membrane interface to assist the SNAREs in overcoming energetic barriers to membrane fusion.

Several distinctly different mechanisms for syt1 function have been proposed. For example, syt1 might regulate fusion by interacting with the SNAREs or intermediates in the SNARE assembly process, and it has been proposed to interact with individual SNAREs and promote SNARE assembly 13. In some measurements, complexin is observed to be inhibitory to the fusion process, and syt1 has been proposed to act by displacing complexin from the SNARE complex upon the arrival of a Ca2+-signal, thereby promoting zippering of the SNARE complex 14. It has been reported that syt1 forms a ternary complex with SNAREs and membranes in the presence of Ca2+ 15, and it has been proposed that syt1 might act in such a complex by stabilizing the SNAREs and by facilitating their zippering on the membrane surface 16. Synaptotagmin 1 has also been observed to bridge bilayers 17; 18; 19 and to promote the aggregation of vesicles in Ca2+-dependent manner; a process that might facilitate the formation of a close junction between vesicle and plasma membranes. Synaptotagmin also perturbs bilayers, and it has been proposed to act by altering bilayer curvature and assisting in the formation of the hemi-fusion intermediate20.

At the present time, there is limited structural information to support the specific models that have been proposed. Crystal structures for the assembled core SNARE complex 2, a SNARE-complexin complex 21, as well as the fully-zippered SNARE complex containing the transmembrane segments are available 22. There are also crystal structures and solution NMR structures for the individual C2 domains of syntaptotagmin 1 23; 24, as well as a crystal structure for a soluble fragment of syt1 containing the two C2 domains (syt1C2AB)25. Information on syt1 associated with SNAREs or membranes and SNAREs is more limited and has been challenging to obtain. Site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) and EPR spectroscopy have provided information on how the C2 domains of synaptotagmin 1 are positioned on the membrane interface and penetrate bilayers 8; 26; 27, and these data are qualitatively consistent with the results of fluorescence spectroscopy 7. Continuous wave (CW) EPR 28 as well as long-range distance constraints from pulse EPR show that the two domains in syt1C2AB are flexibly linked in solution and remain flexibly linked when bound to bilayers 19. EPR-derived restraints for membrane associated C2AB demonstrate that it bridges bilayers, and the structures that best satisfy the distance constraints orient the two C2 domains so that their Ca2+-binding loops associate with opposing bilayers 19. Recent single molecule FRET (smFRET) data are generally consistent with these EPR data and indicate that the two domains are flexibly linked 29.

A number of approaches have been used to investigate the syt1-SNARE interaction. NMR chemical shift changes in 15N-HSQC spectra of syt1C2AB indicate that in solution syt1 interacts with the assembled SNARE complex primarily through the polybasic face of the C2B domain of syt1 15. This interaction is also seen by CW-EPR in solution where immobilization of spin labels in the polybasic face of C2B is observed due to tertiary contact of the SNAREs with this face of C2B 28. More recent measurements using smFRET suggest that an important interaction between the SNAREs and syt1 takes place on C2B at a site opposite the Ca2+-binding loops (Figure 1), and that the two domains are positioned to interact with the same membrane surface29. This work supports a hypothesis where syt1 acts upon bilayers, while simultaneously interacting with SNAREs. However, these measurements were carried out on a supported bilayer surface which contained only phosphatidylcholine (PC) and lacked negatively charged lipids, such as phosphatidylserine (PS). Thus, membrane attachment of the C2 domains syt1 should not take place under the conditions of these experiments.

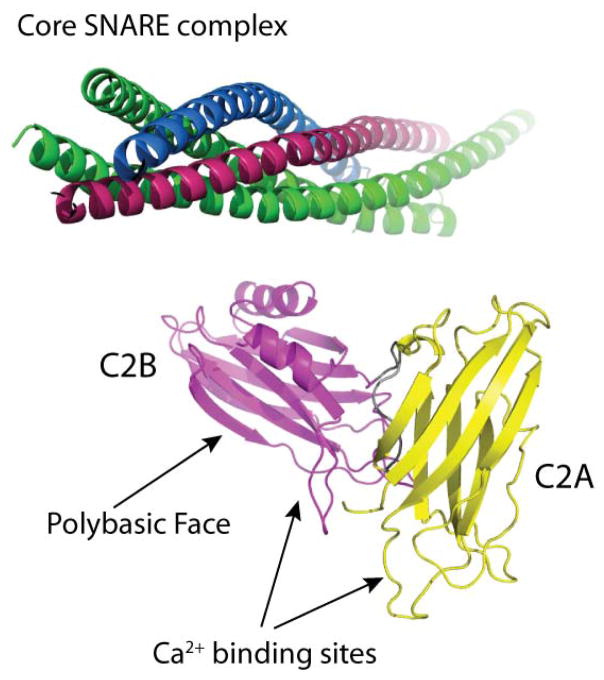

Figure 1.

Model for one of the conformations of synaptotagmin 1 C2AB reported to form in complex with the core SNARE complex, as determined by single molecule FRET 29 (synaptobrevin, blue, syntaxin, green, SNAP-25, green, syt1C2A, yellow, syt1C2B, magenta). In this model syt1C2AB interacts with the core SNARE complex near a positively charged surface on the C2B domain opposite the Ca2+-binding loops.

In the present work, we present the results of both CW and pulse EPR measurements on the interaction between syt1 and the soluble core SNARE complex. The data indicate that in solution, the two C2 domains remain flexibly linked when bound to the SNAREs, consistent with the previous smFRET result. However, simulated annealing using the EPR derived distance constraints indicates that the most populated structure for syt1C2AB when associated with the SNAREs is one where the two C2 domains face in opposite directions. A scan of sites around the surface of syt1C2AB indicates that the polybasic face of C2B is an important site of contact with the SNAREs, although several other points of contact between syt1C2AB and the SNAREs are detected. It was not possible to dock syt1 to the SNAREs and satisfy the observed points of contact, a result which indicates that the syt1/SNARE complex samples multiple conformational states. The implications of these findings for syt1-mediated membrane fusion are discussed.

Results

EPR spectra provide evidence for multiple sites of contact between syt1C2AB and the soluble core-SNARE complex

EPR spectra from the spin labeled side-chain, R1, are sensitive to the local environment at the labeled site. Lineshapes are influenced by the steric interactions made by R1, by the backbone dynamics of the site to which R1 is attached, and by polarity 30; 31; 32. Because the EPR spectrum is sensitive tertiary contact of the nitroxide side-chain, protein-protein interactions have been successfully probed by SDSL and EPR spectroscopy 33; 34. Here, the spin-labeled side chain R1 was incorporated into 21 single cysteine mutants of the soluble fragment of syt1C2AB as described in Methods. These sites are surface exposed, and as shown in Fig. 2, they cover several regions on both the C2A and C2B domains, including areas that have been reported to interact with SNAREs. The spin-labeled side chain (Fig. 2b) is generally non-perturbing to protein structures when it is incorporated into surface sites 35. Moreover, R1 mutants of syt1C2AB have been shown to bind membranes with a mixture of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylserine (PS) in a Ca2+-dependent manner 8; 19, and to bind soluble SNAREs in a Ca2+-independent manner 28.

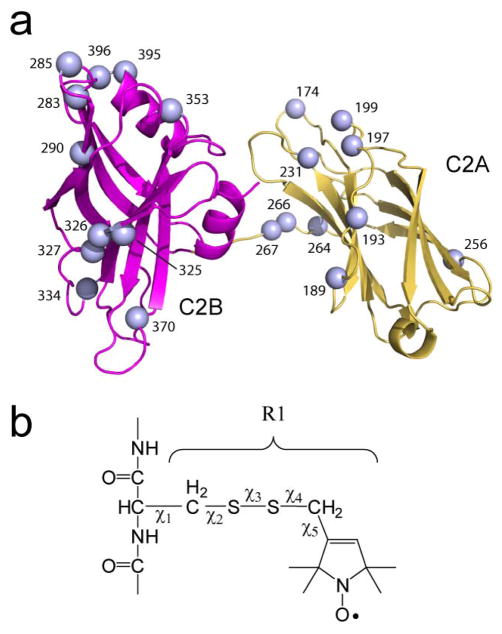

Figure 2.

a) Model of the syt1C2AB fragment showing the Cα carbons of the 21 sites to which b) the spin labeled side chain, R1, has been attached. Five dihedral angles define the position and rotameric states of R1, but rotations about the first 3 angles are largely restricted 39 and certain rotamers for R1 tend to dominate at aqueous exposed sites on proteins 42.

The continuous wave X-band EPR spectra of these mutants were recorded in solution in both the absence and presence of the soluble core SNARE complex, and the normalized spectra are shown in Figure 3. Under the conditions of these experiments, the affinity of syt1C2AB for the soluble SNARE complex is on the order of tens of μM 28, and SNAREs were added in excess and at sufficiently high concentrations to ensure that all the syt1C2AB was associated with SNAREs. The molecular weight of syt1C2AB is sufficiently large so that the EPR spectra will not be influenced by the rotational diffusion of the protein, but will be determined by local backbone dynamics and steric contact of R1 at the labeled site 31; 36.

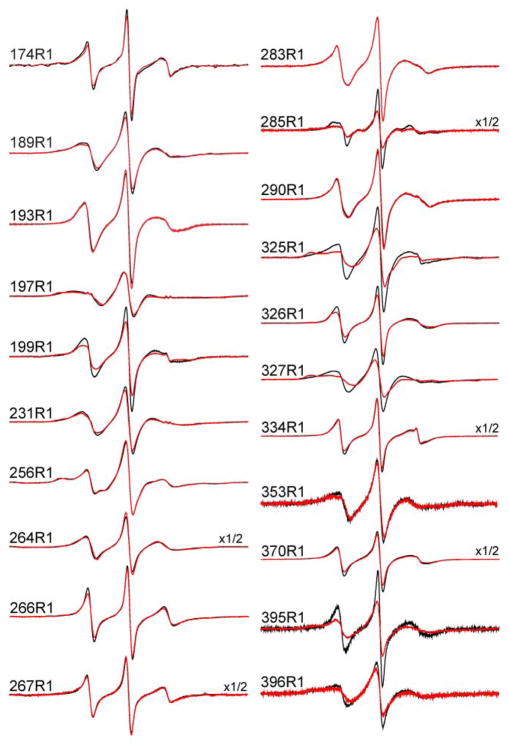

Figure 3.

X-band EPR spectra of single R1 labeled syt1C2AB mutants in the absence (black trace) or presence (red trace) of the soluble SNARE complex. The solution contains 1mM Ca2+ in a buffer of 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 as listed in Methods. The concentration of syt1C2AB is approximately 50 μM and the SNARE complex concentration is at least 100 μM. Spectra are normalized to equivalent spin concentrations, so that the first-derivative amplitudes reflect relative nitroxide motional averaging. The spectra are 100 G scans.

In aqueous solution, most of the spectra in Fig. 3 are typical of spectra seen at exposed aqueous sites, reflecting motion that is rapid on the X-band time scale (1 to 3 ns). Several sites, including 197 and 256, have spectra with broader features that reflect slow side-chain motion due to tertiary contact. In the presence of SNAREs, most sites yield identical EPR spectra, but several sites exhibit significant changes. In particular, a decrease in motional averaging is seen as a decrease in normalized amplitude in Fig. 3 for 199R1 near Ca2+-binding loop 2 in C2A, 325R1, 326R1 and 327R1 in the polybasic face of C2B, and at 285R1 and 395R1, which are near two conserved arginines, R398 and R399 (the “arginine apex”). Figure 4 shows a plot of the changes in the central linewidth of the EPR spectra upon addition of the SNAREs. The central linewidth (ΔHp-p) is most closely related to the correlation time for the R1 nitroxide motion 36, and increases in ΔHp-p indicate decreases in correlation time. The most dramatic changes are seen for the three residues in the polybasic face of C2B, but significant changes show up for residues 285R1, 353R1, 395R1 and 396R1 and near the arginine apex of C2B, as well as sites 197R1 and 199R1 near Ca2+-binding loop 2 of C2A.

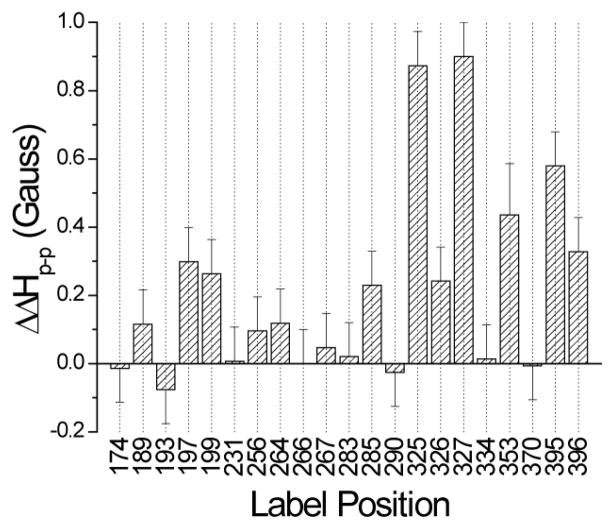

Figure 4.

Differences in the central linewidth (ΔHp-p in Gauss) of the first derivative EPR spectra in Fig. 3 for syt1C2AB spectra obtained in the presence-absence of the soluble SNARE complex. The positive changes in ΔHp-p indicate a restriction in motional averaging of the nitroxide upon the addition of the SNAREs. Changes on the order of 0.1 Gauss or less are within the error of the measurement.

The polybasic face of C2B is a region of extended tertiary contact with the SNAREs

As a check to ensure that changes in the EPR spectra upon SNARE binding seen in Fig. 2 are a result of tertiary contact with the SNAREs, progressive power-saturation was carried out on EPR spectra from syt1C2AB in the presence and absence of soluble SNAREs and in the presence and absence of 10 mM Ni(II)EDDA. This experiment provides a measure of the collision frequency between the Ni(II) complex and the spin label 37, and for sites that appear to exhibit a change in linewidth due to tertiary contact, significant decreases in the collision parameter Π are observed. For example, in the absence of SNAREs, the values of ΠNi(II)EDDA for 199R1, 325R1 and 353R1 are 2.4, 2.3 and 0.85, respectively. In the presence of SNAREs, ΠNi(II)EDDA at these sites has values of 1.4, 0.7 and 0.4, respectively. The decreases in collision parameter indicate that at these labeled sites SNARE interactions are both dampening R1 motion and sterically protecting these labeled sites from the aqueous phase.

The EPR spectra for 325R1 were simulated using the MOMD model of Freed and co-workers 38 as implemented in a program provided by Christain Altenbach (UCLA). Principle values of the hyperfine and g-tensors were used, which are appropriate for R1 in aqueous solution 39. In solution, the spectrum from 325R1 may be fit reasonably well with a single component of nitroxide motion having an isotropic diffusion tensor with a mean correlation time of about 3 ns. In the presence of SNAREs, the EPR spectrum broadens and is dominated by a motional component that is near the rigid limit on the X-band EPR time scale (approx 25 ns correlation time). A fit to this spectrum indicates that this slow motional component represents approximately 60 to 70% of the total spins. The fact that the spectrum for 325R1 in the presence of SNAREs is dominated by a near rigid-limit spectrum and the significant decrease in solvent accessibility indicates that the label is in strong tertiary contact with the SNAREs, and that this interaction must involve at least 60 to 70% of the available C2B domain.

The interaction of syt1C2AB with SNAREs was examined for a number of these sites in the absence of Ca2+. In the absence of Ca2+, similar changes in lineshape to those seen in Fig. 3 are observed upon the addition of the soluble SNARE complex, indicating that the syt1C2AB interactions detected here are not highly dependent upon [Ca2+] levels.

The C2A and C2B domains are flexibly linked in solution and do not exhibit a significant conformational change upon association with the SNARE complex

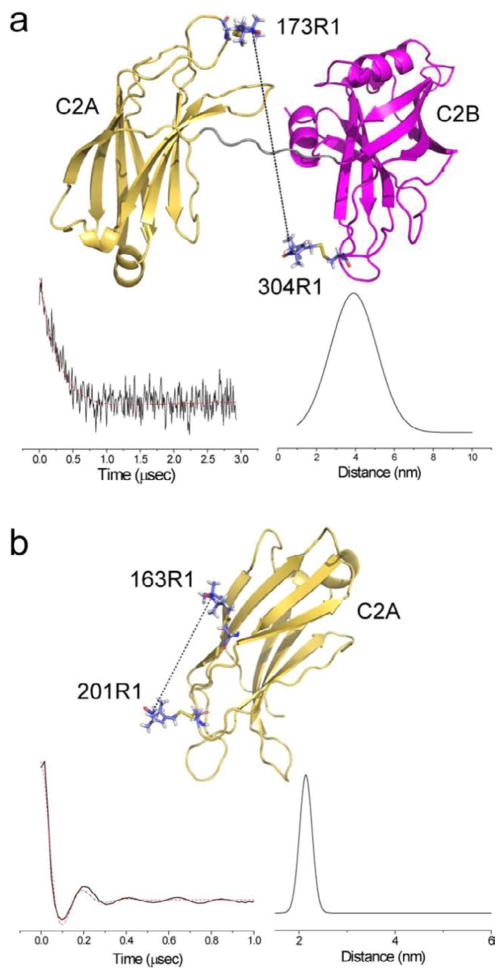

The four-pulse, double electron-electron resonance (DEER) experiment 40; 41 was used here to measure distances and distance distributions between C2A and C2B for seven double mutants in syt1C2AB. Measurements were made in solution in the presence and absence of the soluble core SNARE complex. Shown in Figure 5 are data for the spin-pair 173R1/304R1 when syt1C2AB is bound to the SNAREs. These data are typical of that obtained from these measurements. These background subtracted DEER signals decay and show little oscillation, indicating that there are multiple frequency components in the signal due to a broad inter-spin distance distribution. Also shown in Fig. 5a is the fit to the data, which yields a corresponding Gaussian distribution of distances (see Methods). There is strong evidence that this broad distribution reflects conformational heterogeneity in the relative orientations of the two C2 domains. Previous work has shown that substitution of a conformationally restrained nitroxide analog does not alter the distributions seen for syt1C2AB in solution, nor does placement of the label in the β-stranded regions of the domain 19. Therefore neither R1 side-chain flexibility nor loop conformational exchange contribute significantly to this distribution. Shown in Fig. 5b are DEER signals obtained from a spin-pair within the C2A domain. The signal shows a well-defined oscillation and a narrow distance distribution, which is typical of data obtained from within a single C2 domain or between two labels in a well-structure protein. The relatively narrow distribution for the labeled pair within C2A is consistent with the finding that although 5 dihedral angles link the spin label to the protein backbone, rotameric conversions take place largely about χ4 and χ5 39. The dihedral angles χ1, χ2 and χ3 are known to assume a limited number of rotameric states at surface exposed aqueous sites42; 43.

Figure 5.

a) Background subtracted DEER data and distance distribution obtained from a spin-labeled pair bridging the two Ca2+ binding regions of syt1C2AB. The highly dampened signal is a result of a broad interspin distance distribution, which results from structural heterogeneity in the relative orientation of C2A and C2B. b) the background subtracted DEER signal for two sites within the C2A domain yield a distance, which is in agreement with the C2A structure and the likely rotamers for 201R1 and 163R1, and a narrow distance distribution.

Table 1 summarizes the distances and distance distributions obtained between C2A and C2B of syt1C2AB in the absence and presence of soluble SNARE complex. The distributions were well-fit to a single Gaussian, and the distributions shown represent 1 standard deviation of the distribution. In the absence of SNAREs, the interspin distances range from 39 to 60 Angstroms and are quite broad, indicating that a range of relative conformations are sampled. In the presence of SNAREs, the distances and distributions undergo remarkably little change. Distance differences in the 2 to 3 Angstrom range are likely not significant given the uncertainty in defining the background signal. The 5 Angstrom change seen for the 199R1/304R1 spin pair might be due in part to a side chain conformational change due to a direct interaction with the SNAREs at site 199 (see Fig. 3). The results clearly indicate that there is no well-defined configuration for syt1C2AB when associated with the core SNARE complex, a conclusion that is generally consistent with the results of recent smFRET measurements 29.

Table 1.

Distances (in Angstroms) obtained by DEER between C2A and C2B.

| C2A/C2B mutant | Ca2+ | SNAREs, Ca2+ |

|---|---|---|

| M173R1/V304R1 | 39±9 | 39±14 |

| M173R1/K332R1 | 45±10 | 48±11 |

| R199R1/V304R1 | 37±16 | 42±12 |

| R199R1/K332R1 | 46±9 | 48±10 |

| K244R1/K327R1 | 41±11 | 43±14 |

| K189R1/K327R1 | 43±12 | 42±13 |

| K213R1/V283R1 | 60±18 | 60±15 |

| C2A/C2B mutant | EGTA | SNAREs, EGTA |

| K189R1/K327R1 | 41±13 | 41±14 |

| K213R1/V283R1 | 59±10 | 59±8 |

Distances represent Gaussian fits to the distance distributions determined using the program DEER Analysis 2009 49. The range given represents the SD to the Gaussian fit. Most mutant pairs have approximately a 2 Å distance uncertainty and a 30% uncertainty in the distribution. For the K213R1/V283R1 mutant, there is approximately a 4 Å distance uncertainty and a 50% uncertainty in the distribution. Data listed in the absence of SNAREs were previously reported19.

Table 1 also shows interdomain spin distances for a few double R1 mutants which were examined in the absence of Ca2+, both in the absence and presence the soluble SNAREs. The results are virtually identical to those obtained with Ca2+, and suggest that the conformations sampled by C2A and C2B remain similar either unbound or bound to the SNARE complex.

The C2A and C2B domains spend a significant fraction of time in a back-to-back relative orientation when associated with the SNAREs complex

A model for the most probable structures of syt1C2AB when bound to the soluble SNARE complex was generated using a simulated annealing routine adapted from the XPLOR-NIH package (see Methods). In this approach, C2A is essentially docked to C2B in a manner that best fits the known structural restraints. These restraints included the most populated spin-spin distances measured here (Table 1), the fact that a portion of the linker connecting C2A and C2B is known to be flexible when C2AB is associated with the SNAREs 28, the experimentally determined configurations of the spin labeled side chain R143, and the solution structures of C2A and C2B 23; 24. Because C2AB is conformationally heterogeneous, the distance restraints used in the simulated annealing were allowed to vary over a range corresponding to 2/3 σ of the Gaussian fit to the DEER data.

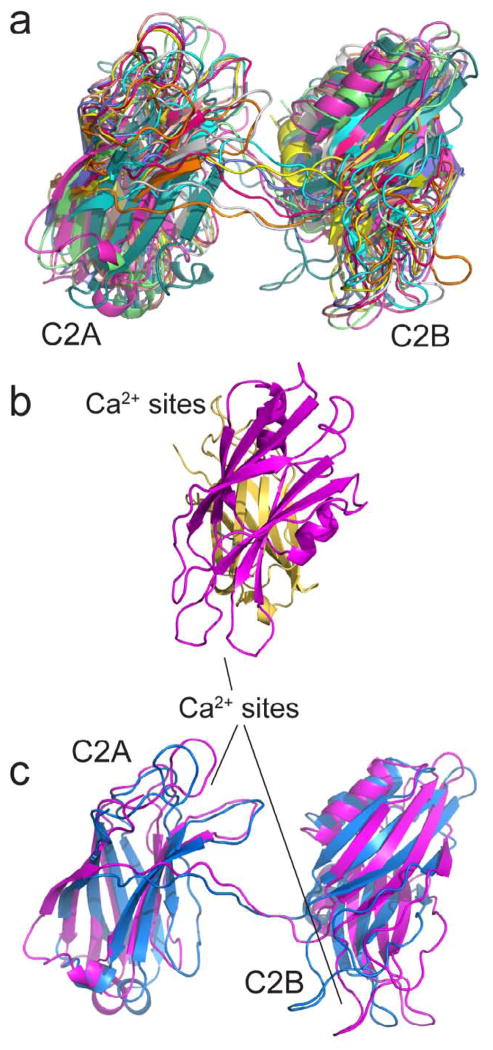

Shown in Fig. 6a is an alignment of the ten lowest energy structures of syt1C2AB bound to the soluble SNARE complex in the presence of Ca2+. There is considerable variability in the structures that are obtained, where the backbone RMSD for the 10 aligned structures in Fig. 6a is 6.55±1.83 Å. This RMSD is, however, highly dependent upon the width of the distance distribution that is used in the simulated annealing. In these structures, the centers of the two domains are separated by roughly 40 Angstroms, and there is no strong inter-domain contact between C2A and C2B. The Ca2+-binding loops of the two domains are also aligned in roughly opposite directions. Figure 6b shows a side view of the average structure of C2AB when bound to the SNAREs, where the tilt angle between the normal of the domains is about 40–60°. Figure 6c shows a comparison of the average structures obtained for syt1C2AB in solution and when bound to the SNAREs. For the solution structure, distance restraints generated previously 19 were used as restraints for the 7 double R1 labeled syt1C2AB listed in Table 1. The two average structures are remarkably similar, and the separation between the centers of the two domains is also approximately 40 Å.

Figure 6.

Aqueous structures of syt1C2AB in the presence of Ca2+ and bound to the soluble SNARE complex. (a) An alignment of the 10 lowest energy structures from the simulated annealing incorporating the SNARE-bound distance restraints in Table 1 and allowing linker region residues 266 to 272 to be flexible. (b) side view of the average structure from the (20) lowest conformations - C2A (yellow), C2B (magenta). (c) Average of the 20 lowest energy structures when C2AB is bound to the SNARE complex (magenta) and in the absence of the SNARE complex (blue).

It should be recognized that the two C2 domains of syt1 sample a variety of relative orientations; and, while the structures in Figure 6 represent conformations of syt1C2AB that are most likely to be populated based upon the pulse EPR data, no one structure should be taken too literally.

Discussion

In spite of a significant level of effort, the mechanism by which syt1 mediates Ca2+-triggered synchronous neurotransmitter release is not well-understood. In part, this difficulty is due to the fact that syt1 makes interactions both with bilayers and with SNAREs, and the fact that conventional methods have failed to provide a structure for the syt1-SNARE complex. In the work presented here, we examined the interactions between syt1 and the core SNARE complex using SDSL and determined an average structure for syt1 bound to SNAREs.

The EPR spectra presented in Fig. 3 provide evidence that there are several sites of contact between syt1 and the soluble SNARE complex. For syt1, interactions with SNAREs are seen in the polybasic face of C2B, a region opposite the Ca2+-binding region of C2B, and a region near loop 2 of C2A. These observations are consistent with previous work, where solution NMR indicated contact at the polybasic face of C2B 15, smFRET provided evidence for an interaction opposite the Ca2+-binding region 29, and cross-linking indicated that there were interactions of loop 2 in C2A with SNAP-25 44. Although there is clear evidence for contact between syt1 and SNAREs, distances and distance distributions measured by pulse EPR (Table 1) indicate that C2A and C2B do not assume a well-defined relative orientation and yield a structurally heterogeneous complex when associated with the SNAREs. This finding is consistent with data obtained by NMR and smFRET 15; 29.

The distances and distance distributions obtained from pulse EPR were used to generate a model for the structure of syt1C2AB when associated with the SNARE complex, Fig. 6, which indicates that the Ca2+-binding loops of the two domains face in roughly opposite directions. This orientation positions the two domains so that they might interact with opposing bilayers, as observed previously for syt1C2AB when associated with POPC:POPS bilayers 19.

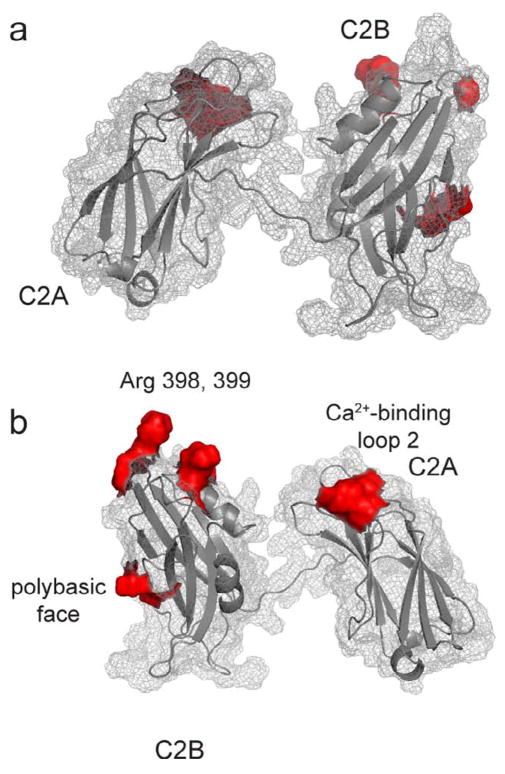

Shown in Fig. 7 is the average structure of syt1C2AB obtained by simulated annealing along with sites of contact with the SNAREs on the protein surface. Based upon the highly immobilized lineshapes and the populations of spins in tertiary contact, contact at the polybasic face appears to be an important site of interaction with the SNAREs. It is possible to satisfy contacts in both the polybasic face and the portions arginine apex by docking C2B to the SNARE complex; however, it is not possible to establish contacts with the SNARE complex at all the points of contact shown in Fig. 7 with a single configuration of syt1 bound to the SNAREs. Based upon lineshapes and changes in aqueous accessibility, contact with loop 2 of C2A appears to be more transient than the two regions of contact on C2B. If C2A were only transiently contacting the SNAREs, while C2B remained associated, it might explain why there is a high-degree of structural heterogeneity is present for syt1C2AB when it is associated with the SNAREs. The model that emerges for the synt1-SNARE interaction is one where the complex between syt1C2AB and the SNAREs is heterogeneous and fluctuates between several structural substates.

Figure 7.

Average structure for syt1C2AB when bound to the soluble SNARE complex (from Fig. 6b) with the sites of interaction with the SNAREs determined from the CW EPR data (red regions). a) and b) show two different sides of the average structure. Simultaneous docking of this structure to bring each of the regions shown in red in contact with the SNAREs is not possible. This finding is consistent with the DEER data, which indicate that the sytC2AB - SNARE complex is structurally heterogeneous and that multiple modes of binding exist for this protein-protein interaction.

The interactions detected between syt1C2AB and the SNAREs, as well as the model generated in Figure 6 by EPR, are different than the model obtained by smFRET (Fig. 1); which is based upon a subset of the FRET data. This configuration is thought to correspond to a specific structural substate of the syt1C2AB-SNARE interaction 29. The CW EPR and the smFRET are consistent with this model to the extent that they both detect an interaction near the arginine 398, 399 apex of C2B. However, other interactions that are at least or more important than the interactions at the arginine apex are also detected by EPR. It should be noted that the SNAREs were added here in excess relative to syt1C2AB, and both protein components were present at high concentrations relative to the affinity measured between syt1C2AB and the SNAREs 28. As a result, any energetically favored substate should be well-populated.

The role of the interaction between syt1 and the core SNARE complex remains uncertain. The relatively weak binding of syt1C2AB to the isolated SNARE complex, and the conformational heterogeneity that is observed, suggest that this interaction is not highly specific. This type of interaction might help localize syt1 to an appropriate region at the focal site of fusion; however, it seems less likely that this type of heterogeneous interaction plays an important role in regulating SNARE activity. It has been suggested that the interaction between syt1 and SNAREs might be stabilized on the bilayer surface 16. However, whether such stabilization takes place on the membrane interface remains to be tested. Stabilizing a specific syt1/SNARE interaction would require more than an increase in the effective SNARE concentration on the membrane interface; it would require a change in energetics for specific syt1/SNARE substates.

In summary, site-directed spin labeling and EPR spectroscopy have been used to examine the interaction between syt1 and the assembled SNARE complex in solution. Interactions with the SNAREs are observed at multiple sites on syt1C2AB, and provide a strong indication that the complex between these two proteins samples multiple conformations. Moreover, pulse EPR spectroscopy demonstrates that the two domains of syt1, which are flexibly linked in solution, remain flexibly linked when fully bound to the SNAREs. Using EPR-derived distance distributions, the more populated configurations of syt1C2AB are those where the Ca2+-binding sites of the two domains are pointed in roughly opposing directions.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis, Protein Expression and Purification

DNA of rat syt1 (P21707), was obtained from Dr. Carl Creutz (Pharmacology Department, University of Virginia) in the pGEX-KG vector encoding amino acid residues 96–421 (syt1C2AB) 45. The single native cysteine residue at position 277 was mutated to alanine by typical polymerase chain reaction (PCR) strategies. A QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used to produce single and double-cysteine mutants of C2AB, and all cysteine substitutions were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The expression and purification syt1C2AB was carried out as described previously 8. Following affinity purification, steps were taken to remove residual GST and thrombin, and an additional anion exchange step was added to remove nucleic acid contaminants associated with the protein27. Syt1C2AB prepared in this manner, binds Tb3+ (a Ca2+ analog), membranes, and appears to be correctly folded as indicated by CD spectroscopy and FTIR 8; 28. Directly following anion exchange chromatography, pure fractions of syt1C2AB cysteine mutants were spin-labeled as described previously using the sulfhydryl reactive spin label MTSL, (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, ON, Canada) 8.

The DNA of His6-tagged soluble SNARE motif fusion proteins, syntaxin 1A (residues 180–262), SNAP-25 (residues 1–206), synaptobrevin (residues 1–96), encoded in vector pET-28a (as well as the synaptobrevin and syntaxin constructs listed below for membrane reconstitution) were kindly provided by R. Jahn and D. Fasshauer (Max-Plank-Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen, Germany). The recombinant proteins were expressed as His6-tagged fusion proteins and purified by Ni2+-Sepharose affinity chromatography as described previously 28; 46. After the overnight assembly of the purified monomers, the ternary (syntaxin–SNAP-25–synaptobrevin) complex was first purified using anion exchange chromatography. The minimal core complex was then further purified by size exclusion chromatography as described previously 28; 46.

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Measurements

Continuous wave X-band EPR measurements were performed on 8 μL of sample loaded into glass capillaries with 0.60 mm i.d. × 0.84 mm o.d. (Fiber Optic Center, Inc., New Bedford, MA). Protein concentrations for spin-labeled samples of syt1C2AB mutants varied from 50–100 μM. EPR spectra were acquired in the presence of 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM Ca2+, pH 7.4, or with the addition of 5 mM EGTA. The molar ratio of syt1C2AB: SNARE complex ranged from 1:1.5 to 1:2. EPR spectra were obtained using a modified Varian E-line 102 series or Bruker Elexsys-E500 (Bruker BioSpin, Billerica, MA) spectrometer with a loop gap XP-0201 resonator (Molecular Specialties, Milwaukee, WI), or using a Bruker EMX spectrometer fitted with an ER4123D dielectric resonator. All spectra were taken at X-band using 2 mW incident microwave power and 1 G modulation amplitude. The scan range for the spectrum was 100 Gauss. Spectra were baseline corrected and normalized using LabVIEW software provided by Christian Altenbach (UCLA).

Continuous-wave power saturation experiments were performed on the syt1C2AB mutants in the presence and absence of SNAREs as described previously 47. Changes in the derived P1/2 values were used to calculate the collision parameter, Π, in the presence of the paramagnetic reagent Ni(II)EDDA. Ni(II)EDDA was used at a concentration of 10 mM, but the ΔP1/2 values were scaled to yield the effective collision parameter at a concentration of 20 mM.

Pulse-EPR measurements were performed on 25–30 μL of sample loaded into quartz capillaries with 2.00 mm i.d. × 2.40 mm o.d. (Fiber Optic Center, Inc., New Bedford, MA). DEER samples were prepared with 1:1 to 1:2 molar ratio of syt1C2AB: SNARE complex. The protein concentration of double spin-labeled syt1C2AB mutants varied from 100–200 μM in the presence (1mM Ca2+) or absence of calcium (5mM EGTA). Samples of syt1C2AB and SNARE complex in solution contained 20% v/v glycerol. DEER samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and the data were recorded at 78K on a Bruker Elexsys-E580 spectrometer fitted with an ER4118X-MS3 split ring resonator (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). Data were acquired using a four-pulse DEER sequence 48 with a 16 ns π/2 and two 32 ns π observe pulses separated by a 32 ns π pump pulse. The dipolar evolution times were typically 2.2–2.5 μs, with several samples taken out to 3.0 μs. The pump frequency was set to the center maximum of the nitroxide spectrum and the observer frequency was set to the low field maximum, typically 65–70 MHz higher. The phase-corrected dipolar evolution data were processed assuming a 3D background and Fourier transformed, and the distance distributions were obtained with Gaussian fits using the DeerAnalysis2009 package 49.

Modeling the Conformation of syt1C2AB when Bound to the SNARE complex

Model structures of syt1C2AB were determined as described previously 19. Structures were calculated using an Xplor-NIH simulated annealing procedure similar to that used for protein-protein docking 50; 51. The tandem C2A-C2B structure for simulated annealing was obtained by appending the four missing residues of the linker region (E268-E269-Q270-E271) to the high-resolution NMR structures of C2A (residues 140-267) 24 and C2B (residues 272-419) 23 (PDB ID: 1BYN and 1K5W, respectively). The linker region retains its flexibility when syt1C2AB is bound to the SNARE complex; and as a result, residues 266 to 272 were not assigned a secondary structure in the simulated annealing28. Positions 173, 189, 199, 213, 244 of C2A and 283, 304, 327, 332 of C2B were mutated in silico to Cys and MTSL side chains were attached with the Xplor-NIH addAtoms.py script. The first two dihedral angles from the backbone for R1, X1 and X2, were set to −60° 43. Seven inter-spin distances were used as input for an Xplor-NIH simulated annealing protocol 50; 51 to determine the relative conformation of C2AB-Ca2+ in solution while bound to the SNARE complex. The uncertainty in the inter-spin distances was set using two thirds of the standard deviation (SD) of the DEER-derived Gaussian distance distributions. Simulated annealing and energy minimization were performed as described previously 19. The coordinates of average structures were obtained by averaging the coordinates of twenty individual lowest energy simulated annealing structures (out of one hundred generated structures) best fitted to each other. Structures were visualized and analyzed and figures were generated with the program PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC, Palo Alto, CA).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Christian Altenbach (UCLA) for providing LabVIEW programs used to process and simulate EPR spectra. We also acknowledge the assistance of the laboratories of Lukas Tamm (University of Virginia) and Reinhard Jahn (Max-Plank-Institute Göttingen, Germany) for help with the expression, purification and reconstitution of the soluble SNARE complex. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, NIGMS, GM 072694.

Abbreviations

- CW

continuous wave

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

- DEER

double electron-electron resonance

- R1

spin-labeled side chains produced by derivatization of a cysteine with a methanethiosulfonate spin label

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- SD

standard deviation

- SDSL

site-directed spin labeling

- syt1

synaptotagmin 1

- syt1C2AB

soluble fragment of syt1 containing the C2A and C2B domains

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs--engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1998;395:347–53. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber T, Zemelman BV, McNew JA, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92:759–72. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brose N, Petrenko AG, Sudhof TC, Jahn R. Synaptotagmin: a calcium sensor on the synaptic vesicle surface. Science. 1992;256:1021–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1589771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizo J, Chen X, Arac D. Unraveling the mechanisms of synaptotagmin and SNARE function in neurotransmitter release. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:339–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai J, Chapman ER. The C2 domains of synaptotagmin--partners in exocytosis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai J, Tucker WC, Chapman ER. PIP2 increases the speed of response of synaptotagmin and steers its membrane-penetration activity toward the plasma membrane. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:36–44. doi: 10.1038/nsmb709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrick DZ, Sterbling S, Rasch KA, Hinderliter A, Cafiso DS. Position of synaptotagmin I at the membrane interface: cooperative interactions of tandem C2 domains. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9668–74. doi: 10.1021/bi060874j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman ER. How does synaptotagmin trigger neurotransmitter release? Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:615–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062005.101135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmins: why so many? J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7629–7632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker WC, Chapman ER. Role of synaptotagmin in Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Biochem J. 2002;366:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Kim-Miller MJ, Fukuda M, Kowalchyk JA, Martin TF. Ca2+-dependent synaptotagmin binding to SNAP-25 is essential for Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Neuron. 2002;34:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhalla A, Chicka MC, Tucker WC, Chapman ER. Ca(2+)-synaptotagmin directly regulates t-SNARE function during reconstituted membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:323–30. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaub JR, Lu X, Doneske B, Shin YK, McNew JA. Hemifusion arrest by complexin is relieved by Ca2+-synaptotagmin I. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:748–50. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai H, Shen N, Arac D, Rizo J. A quaternary SNARE-synaptotagmin-Ca2+-phospholipid complex in neurotransmitter release. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:848–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizo J, Rosenmund C. Synaptic vesicle fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:665–74. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arac D, Chen X, Khant HA, Ubach J, Ludtke SJ, Kikkawa M, Johnson AE, Chiu W, Sudhof TC, Rizo J. Close membrane-membrane proximity induced by Ca(2+)-dependent multivalent binding of synaptotagmin-1 to phospholipids. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:209–17. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connell E, Giniatullina A, Lai-Kee-Him J, Tavare R, Ferrari E, Roseman A, Cojoc D, Brisson AR, Davletov B. Cross-linking of phospholipid membranes is a conserved property of calcium-sensitive synaptotagmins. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrick DZ, Kuo W, Huang H, Schwieters CD, Ellena JF, Cafiso DS. Solution and membrane-bound conformations of the tandem C2A and C2B domains of synaptotagmin 1: Evidence for bilayer bridging. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:913–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martens S, Kozlov MM, McMahon HT. How synaptotagmin promotes membrane fusion. Science. 2007;316:1205–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1142614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Tomchick DR, Kovrigin E, Arac D, Machius M, Sudhof TC, Rizo J. Three-dimensional structure of the complexin/SNARE complex. Neuron. 2002;33:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein A, Weber G, Wahl MC, Jahn R. Helical extension of the neuronal SNARE complex into the membrane. Nature. 2009;460:525–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez I, Arac D, Ubach J, Gerber SH, Shin O, Gao Y, Anderson RG, Sudhof TC, Rizo J. Three-dimensional structure of the synaptotagmin 1 C2B-domain: synaptotagmin 1 as a phospholipid binding machine. Neuron. 2001;32:1057–69. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao X, Fernandez I, Sudhof TC, Rizo J. Solution Structures of the Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound C2A Domain of Synaptotagmin I: Does Ca2+ Induce a Conformational Change? Biochemistry. 1998;37:16106–16115. doi: 10.1021/bi981789h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuson KL, Montes M, Robert JJ, Sutton RB. Structure of Human Synaptotagmin 1 C2AB in the Absence of Ca2+ Reveals a Novel Domain Association. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13041–13048. doi: 10.1021/bi701651k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frazier AA, Roller CR, Havelka JJ, Hinderliter A, Cafiso DS. Membrane-bound orientation and position of the synaptotagmin I C2A domain by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 2003;42:96–105. doi: 10.1021/bi0268145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rufener E, Frazier AA, Wieser CM, Hinderliter A, Cafiso DS. Membrane-bound orientation and position of the synaptotagmin C2B domain determined by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 2005;44:18–28. doi: 10.1021/bi048370d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang H, Cafiso DS. Conformation and membrane position of the region linking the two C2 domains in synaptotagmin 1 by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12380–8. doi: 10.1021/bi801470m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi UB, Strop P, Vrljic M, Chu S, Brunger AT, Weninger KR. Single-molecule FRET-derived model of the synaptotagmin 1-SNARE fusion complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:318–24. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubbell WL, Cafiso DS, Altenbach C. Identifying conformational changes with site-directed spin labeling. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:735–9. doi: 10.1038/78956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Columbus L, Hubbell WL. A new spin on protein dynamics. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:288–95. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fanucci GE, Cafiso DS. Recent advances and applications of site-directed spin labeling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:644–53. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin Z, Wertz SL, Jacob J, Savino Y, Cafiso DS. Defining protein-protein interactions using site-directed spin-labeling: the binding of protein kinase C substrates to calmodulin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13272–6. doi: 10.1021/bi961747y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crane JM, Mao C, Lilly AA, Smith VF, Suo Y, Hubbell WL, Randall LL. Mapping of the docking of SecA onto the chaperone SecB by site-directed spin labeling: insight into the mechanism of ligand transfer during protein export. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:295–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McHaourab HS, Lietzow MA, Hideg K, Hubbell WL. Motion of spin-labeled side chains in T4 lysozyme. Correlation with protein structure and dynamics. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7692–704. doi: 10.1021/bi960482k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Columbus L, Hubbell WL. Mapping backbone dynamics in solution with site-directed spin labeling: GCN4-58 bZip free and bound to DNA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7273–87. doi: 10.1021/bi0497906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farahbakhsh ZT, Altenbach C, Hubbell WL. Spin labeled cysteines as sensors for protein-lipid interaction and conformation in rhodopsin. Photochem Photobiol. 1992;56:1019–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb09725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Budil DE, Lee S, Saxena S, Freed JH. Nonlinear-least-squares analysis of slow-motion EPR spectra in one and two dimensions using a modified Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Series A. 1996;120:155–189. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Columbus L, Kalai T, Jeko J, Hideg K, Hubbell WL. Molecular motion of spin labeled side chains in alpha-helices: analysis by variation of side chain structure. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3828–46. doi: 10.1021/bi002645h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeschke G, Polyhach Y. Distance measurements on spin-labelled biomacromolecules by pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2007;9:1895–1910. doi: 10.1039/b614920k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiemann O, Prisner TF. Long-range distance determinations in biomacromolecules by EPR spectroscopy. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 2007;40:1–53. doi: 10.1017/S003358350700460X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleissner MR, Cascio D, Hubbell WL. Structural origin of weakly ordered nitroxide motion in spin-labeled proteins. Protein Sci. 2009;18:893–908. doi: 10.1002/pro.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo Z, Cascio D, Hideg K, Hubbell WL. Structural determinants of nitroxide motion in spin-labeled proteins: Solvent-exposed sites in helix B of T4 lysozyme. Protein Science. 2008;17:228–239. doi: 10.1110/ps.073174008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lynch KL, Gerona RR, Larsen EC, Marcia RF, Mitchell JC, Martin TF. Synaptotagmin C2A loop 2 mediates Ca2+-dependent SNARE interactions essential for Ca2+-triggered vesicle exocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4957–68. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Damer CK, Creutz CE. Synergistic membrane interactions of the two C2 domains of synaptotagmin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:31115–31123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fasshauer D, Eliason WK, Brunger AT, Jahn R. Identification of a minimal core of the synaptic SNARE complex sufficient for reversible assembly and disassembly. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10354–62. doi: 10.1021/bi980542h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frazier AA, Wisner MA, Malmberg NJ, Victor KG, Fanucci GE, Nalefski EA, Falke JJ, Cafiso DS. Membrane orientation and position of the C2 domain from cPLA2 by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6282–92. doi: 10.1021/bi0160821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pannier M, Veit S, Godt A, Jeschke G, Spiess HW. Dead-Time Free Measurement of Dipole-Dipole Interactions between Electron Spins. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2000;142:331–340. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeschke G, Chechik V, Ionita P, Godt A, Zimmermann H, Banham J, Timmel C, Hilger D, Jung H. DeerAnalysis2006—a comprehensive software package for analyzing pulsed ELDOR data. Applied Magnetic Resonance. 2006;30:473–498. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Marius Clore G. Using Xplor-NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2006;48:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Marius Clore G. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]