Abstract

Rationale and objectives

Quadriceps strength relates to exercise capacity and prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We wished to quantify the prevalence of quadriceps weakness in COPD, and hypothesised that it would not be restricted to patients with severe airflow obstruction or dyspnoea.

Methods

Predicted quadriceps strength was calculated using a regression equation (incorporating age, gender, height and fat-free mass), based on measurements from 212 healthy subjects. The prevalence of weakness (defined as observed values 1.645 standardised residuals below predicted) was related to GOLD stage and Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea score in two cohorts of stable COPD outpatients recruited from the United Kingdom (n=240) and the Netherlands (n=351).

Main results

32% and 33% of UK and Dutch COPD patients had quadriceps weakness. A significant proportion of patients in GOLD stages 1 and 2, or with an MRC dyspnoea score of 1 or 2, had quadriceps weakness (28% and 26% respectively). These values rose to 38% in GOLD stage 4, and 43% in patients with an MRC Score of 4 or 5.

Conclusion

Quadriceps weakness was demonstrable in one-third of COPD patients attending hospital respiratory outpatient services. Quadriceps weakness exists in the absence of severe airflow obstruction or breathlessness.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may exhibit cachexia or skeletal muscle dysfunction (1). Reduced quadriceps strength contributes to poor exercise performance (2) and has been linked to increased health care utilisation (3) and mortality (4). Whilst the pathophysiology of skeletal muscle dysfunction and wasting is multi-factorial, inactivity is likely to play a key role. Reduced muscle strength is more readily demonstrable in the lower limbs (5, 6) of COPD patients and a “downward disease spiral” has been hypothesised, in which advancing dyspnoea leads to a sedentary lifestyle and de-conditioning of the locomotor muscles, and thus further inactivity (7). Reduced exercise capacity has been related to increased dyspnoea measured by the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale (8) in the presence of preserved whole body fat-free mass indices (9). Improved quadriceps muscle strength and endurance are thought to underlie much of the increased exercise capacity observed following multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD (10). Access to such programmes remains challenging (11); international guidelines recommend pulmonary rehabilitation for patients only with a Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea score of 3 or above (12).

Isometric maximum voluntary contraction strength (QMVC) is commonly used to quantify quadriceps strength and is typically reduced in moderate-to-severe COPD patients by approximately 30% when compared with age and gender matched healthy subjects (5, 13). However, quadriceps strength varies widely in such healthy subjects; in the classic description of QMVC measurement, strength was normalised to body weight (14). Predictive equations have been applied to COPD cohorts, but these were derived from a small number of healthy subjects (15). This study aimed to identify the lower limit of normal quadriceps strength adjusting for anthropometric factors across an age range comparable to that typically observed in COPD, and estimate the prevalence of quadriceps weakness in two independent patient cohorts. We wished to quantify the prevalence of quadriceps weakness in COPD, and hypothesised that it would not be restricted to patients with severe airflow obstruction, dyspnoea or fat-free mass loss.

METHODS

Patients and study design

Isometric quadriceps maximum voluntary contraction force (QMVC) was measured in 212 healthy volunteers (aged 40-90) who had participated in research studies at the Muscle Laboratories at King's College Hospital and Royal Brompton Hospital, between October 2002 and July 2008. Raw data from some subjects has contributed to previous work (5, 16, 17). Subjects were recruited by advertisement or from a register of healthy elderly volunteers maintained on the King's Hospital campus by the Department of Elderly Medicine. Although healthy volunteers had an FEV1>80% predicted and FEV1/FVC ratio >70%, they included both never and ex-smokers. All reported no respiratory symptoms and no co-morbidity affecting the legs. QMVC measurements were related to anthropometric variables of age, gender, height, and fat-free mass (FFM), and a regression equation derived to predict QMVC.

Two COPD cohorts were analysed retrospectively; predicted QMVC strength was calculated from the healthy regression equation. As with controls, raw data from some patients has previously been reported (5, 16-18). The first COPD cohort of 240 subjects comprised stable community dwelling patients who had accessed hospital outpatient services and participated in physiological research at the UK centers above. The second COPD cohort comprised 351 patients attending their first clinical assessment at a Dutch rehabilitation hospital (Ciro, Center of Expertise for Chronic Organ Failure, Horn, NL) between December 2005 and October 2007, following referral from their treating respiratory physician. UK healthy volunteers and patients included all those in whom both QMVC and a complete set of anthropometric variables had been measured. Dutch patients were identified from patients in whom non-volitional assessment of quadriceps strength had additionally been performed. All centers had local ethical committee approval and participants gave written informed consent.

The prevalence of quadriceps weakness was calculated in the UK and Dutch COPD cohorts according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage. (19). The role of exertional dyspnoea in the aetiology of quadriceps weakness and the relationship with other prognostic variables was explored using additional data (MRC dyspnoea score (8) and BODE index (20)) available for the Dutch COPD cohort.

Measurements

Both clinical centres participated in the 2003-6 ENIGMA project (QLK6-CT-2002-02285) to investigate muscle function in COPD (18, 21), and measured supine isometric QMVC with the knee joint at 90°, using apparatus described by Edwards et al. (14); measurement techniques were standardized by reciprocal visits at the start of the project. QMVC was the highest mean force that could be sustained over 1 second. We accepted the greatest of at least 3 reproducible efforts and care was taken to immobilize the hip joint. Fat-free mass (FFM) was estimated using 50Hz electrical bioimpedance (Bodystat® 1500, Bodytstat®, Isle of Man, UK) (22) in the non-fasted state. Spirometry and pulmonary function tests (diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), lung volume estimation by body plethysmography and arterial blood gas analysis) were performed according to European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society (ERS/ATS) recommendations (23-25). Additional measurements in the Dutch cohort included whole-body and regional (lower-limb) lean mass by dual energy x-ray absorbtiometry (DEXABODY and DEXALEG) (26). Non-volitional strength assessment used supramaximal magnetic femoral nerve stimulation to generate the quadriceps twitch response (TwQ) (27). Unpotentiated quadriceps twitches were obtained using a 70mm figure of eight coil (Magstim Co. Ltd, Whitland, UK), following 20-minutes of rest on the same apparatus as that described for the QMVC; the mean of a minimum of 5 reproducible twitches was used for analysis. The six-minute walk distance (6MWD) was measured according to published guidelines after a practice walk (28). Peak cycle work (Wpeak) was measured by symptom-limited cycle ergometery. 1-minute of unloaded cycling was followed by 10 W/minute increments. Patients cycled at 60 revolutions per minute until exhaustion (29). Health related quality of life was measured by the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (30).

Statistical analysis

Analyses used SPSS® Version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) or GraphPad Prism® Version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California, USA). Between-group comparisons used analysis of variance (ANOVA), with post-hoc analysis (Bonferonni) for more than 2-groups. Correlations were described using Pearson coefficients to 2 decimal places. Multiple linear regression using a single entry step of anthropometric co-variables correlated with QMVC strength, analysed the dependence of QMVC in healthy subjects on height, FFM, age and gender. Weakness was defined in patients as a QMVC below 1.645 standardised residuals from the healthy predicted value. %predicted FEV1 was added as a co-variable in a similar analysis of all COPD patients. The prevalence of QMVC weakness between COPD cohorts and genders was compared by the Chi-squared test; logistic regression was used to assess the likelihood of quadriceps weakness being present according to co-variables of disease severity (FEV1 or GOLD Stage) and/or dyspnoea (MRC Dyspnoea Scale). GOLD or MRC classes were combined with the next level of severity if fewer than 50 patients were counted. Statistical significance was accepted for P values below 0.05. Additional comparisons were made between patients with weak and normal quadriceps strength in the Dutch cohort. The effect of weakness on 6MWT distance and Wpeak was analysed using multiple linear regression, adjusting for anthropometric and pulmonary function co-variables that differed significantly between these groups. Volitional and non-volitional quadriceps strength normalised for leg muscle mass, were also compared.

RESULTS

Quadriceps strength in healthy subjects

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. In healthy subjects, QMVC was greater in males (+13.3kg, 95% CI: +10.5kg to +16.1kg, p<0.001) and correlated with age (r=0.29, p<0.001), height (0.56, p<0.001) and FFM (0.68, p<0.001). The regression equation describing predicted QMVC force (r2=0.51) in kg was:

Multiple linear regression analysis identified age and FFM as statistically independent factors (Table 2). All covariables had a calculated tolerance greater than 0.1, suggesting none was redundant in the above equation. The residual standard deviation from the analysis was 8.58 kg: therefore patients with an [(Observed QMVC - Predicted QMVC)/8.58] less than −1.645, were considered weak. 8% of healthy subjects had weak quadriceps based on this cut-off. Predicted QMVC was similar in the COPD groups (UK: 74.8(20.5)%; NL: 72.2(18.2)%, p=0.353). Allowing for the dependence of quadriceps strength on the anthropometric variables reported in healthy subjects, each percentage point loss of FEV1 in COPD was associated with a reduction in QMVC of only 47g (95% CI: −13g to −82g, P=0.007, Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Baseline characteristics of the three cohorts studied. Values are mean (SD) unless indicated. Oral corticosteroid use defined as greater than 5mg of prednisolone per day.

| Healthy | COPD |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=212) | UK (n=240) | NL (n=351) | |

| Age (years) | 64 (9) | 66 (8) | 63 (10) |

| Sex (%male) | 44 | 73 a | 57 ab |

| Height (m) | 1.67 (0.09) | 1.69 (0.08) | 1.67 (0.08) b |

| FFM (kg) | 47.6 (11.4) | 46.7 (8.3) | 44.3 (8.1) ab |

| QMVC (kg) | 39.5 (12.3) | 32.0 (11.3) a | 29.9 (10.4) ab |

|

| |||

| Inhaled corticosteroid (%) | - | 75 | 83b |

| Long acting beta agonist (%) | - | 74 | 82b |

| Long acting anticholinergic (%) | - | 62 | 64 |

| Oral corticosteroid therapy (%) | - | 10 | 15 |

|

| |||

| Pack years | 10 (17) | 50 (24) a | 36 (16) ab |

| FEV1 (litres) | 2.78 (0.64) | 1.08 (0.51) a | 1.21 (0.55) ab |

| FEV1 (%predicted) | 105 (13.9) | 40.2 (18.9) a | 44 (18) ab |

| PaO2 (kPa) | - | 9.43 (1.45) | 9.37 (1.45) |

| PaCO2 (kPa) | - | 5.19 (0.81) | 5.33 (0.70) b |

Key:

statistically different compared to healthy subjects (p<0.05, ANOVA method);

NL (Dutch) COPD cohort significantly different to UK COPD cohort.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; PaO2/CO2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen/carbon dioxide; BMI, body mass index; FFM(I), fat-free mass (index); QMVC, isometric quadriceps maximum voluntary contraction.

Table 2. Dependence of QMVC on anthropometric factors in COPD.

Results of multiple linear regression analyses of healthy and COPD patients are shown. Regression coefficients indicate the change in QMVC force per unit change of each co-variable indicated. Gender difference represents females compared to males. P values <0.05 suggest statistically independent determinants in the regression equation. Gender did not reach the predetermined level of significance when COPD cohorts were analysed separately.

| Regression coefficient (95% CI) P-value |

||

|---|---|---|

| UK Healthy (n=212) | UK and NL COPD (n=591) | |

| (Constant) |

56.2 (15.1 to 97.4) P=0.008 |

19.6 (0.21 to 39.1) P=0.048 |

| Age (years) |

−0.30 (−0.44 to −0.16) P<0.001 |

−0.31 (−0.38 to −0.24) P<0.001 |

| Sex (F-M) |

−3.42 (−7.28 to 0.42) P=0.081 |

−2.60 (−4.43 to −0.78) P=0.005 |

| Height (cm) |

−0.15 (−0.40 to 0.11) P=0.254 |

−2.47 (−13.44 to 8.49) P=0.657 |

| FFM (kg) |

0.68 (0.45 to 0.91) P<0.001 |

0.81 (0.68 to 0.91) P<0.001 |

| FEV1 (%predicted) |

- | 0.047 (0.013 to 0.082) P=0.007 |

| Model r2 | 0.51 | 0.52 |

Quadriceps strength and GOLD stage

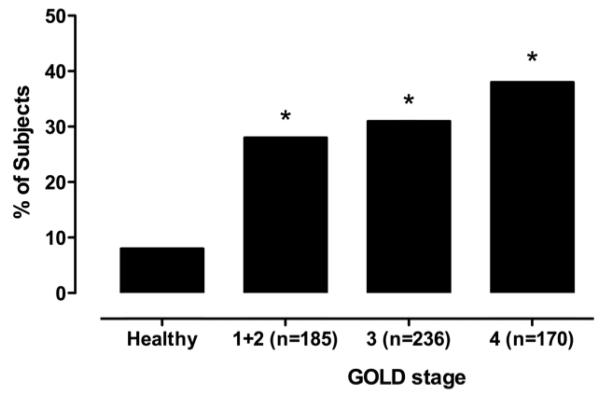

The overall prevalence of quadriceps weakness was 32%, and was statistically similar in men and women, and between COPD cohorts (Table 3). The prevalence of weakness in COPD according to GOLD stage is illustrated in Figure 1. 28% of UK patients and 34% of Dutch patients in the combined GOLD stage 1/2 category demonstrated quadriceps weakness. Unsurprisingly the highest prevalence of weakness was observed in those with the most severe airflow obstruction (38% in GOLD stage 4), however, there was no significant difference in prevalence between GOLD categories shown in Figure 1.

Table 3. Prevalence of quadriceps weakness in COPD.

Percentage (and absolute count) of patients diagnosed with quadriceps weakness, split by gender and disease cohort.

| UK Healthy |

COPD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | NL | UK and NL | ||

| Male | N=94 | N=161 | N=200 | N=361 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 (3.3) | 24.4 (4.8) a | 24.2 (4.5) a | 24.6 (4.4) a |

| FFMI (kg/m2) | 18.8 (2.0) | 16.6 (2.2) a | 16.6 (2.0) a | 16.6 (2.1) a |

| QMVC (kg) | 46.9 (12.3) | 35.2 (10.7) a | 33.9 (10.6) a | 34.4 (10.6) a |

|

| ||||

|

COPD patients with weak QMVC % (N) |

- | 28 (45) | 34 (68) | 31 a (113) |

|

| ||||

| Female | N=118 | N=79 | N=151 | N=230 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.1 (4.2) c | 24.4 (5.0) | 23.2 (4.2) c | 23.6 (4.6) a |

| FFMI (kg/m2) | 15.2 (1.2) c | 15.4 (1.9) c | 14.6 (1.5) abc | 14.9 (1.9) ac |

| QMVC (kg) | 33.6 (8.4) c | 25.7 (9.9) ac | 24.6 (6.9) ac | 24.9 (8.1) ac |

|

| ||||

|

COPD patients with weak QMVC % (N) |

- | 39 (31) | 31 (47) | 34 (78) |

|

| ||||

| Male and female | N=212 | N=240 | N=351 | N=591 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 (3.9) | 24.4 (4.8) | 23.8 (4.4) a | 24.0 (4.6) a |

| FFMI (kg/m2) | 16.8 (2.6) | 16.2 (2.2) a | 15.7 (2.1) ab | 15.9 (2.1) a |

| QMVC (kg) | 39.5 (12.3) | 32.0 (11.3) a | 29.9 (10.4) ab | 30.7 (10.8) a |

|

| ||||

|

COPD patients with weak QMVC % (N) |

- | 32 (76) | 33 (115) | 32 (191) |

BMI, FFMI and QMVC in each group shown for reference Key:

significant difference (P<0.05) compared to healthy subjects;

significant difference between UK and Dutch COPD patients;

significant difference between males and females.

Figure 1.

This study did not include GOLD “stage 0” subjects; however, 107 healthy subjects (50%) had smoking histories in excess of 1-pack year. Healthy subjects were re-analysed post-hoc, adding prior or current smoking status as a group variable. In addition to the dependence of QMVC on the variables previously described, a smoking history was independently associated with a lower QMVC (−3.4kg, 95%CI: −5.7kg to −1.0kg, p=0.005). There was no correlation between QMVC and self-reported pack years; current smoking status did not affect the QMVC in COPD patients.

Quadriceps weakness in COPD and the relationship with a low FFMI

Gender-specific cut-offs to describe a low FFMI in COPD have been proposed (31, 32). Despite the relationship between QMVC and FFM described in Table 3, neither the proposed lower limit of normal FFMI (10th percentile) previously reported from a large well-described Danish cohort (31) nor that observed among healthy subjects in this study, was predictive of quadriceps weakness in COPD.

Quadriceps strength in relation to dyspnoea and BODE score in Dutch patients

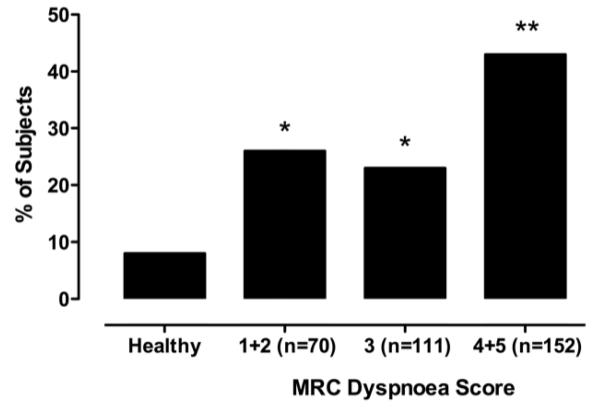

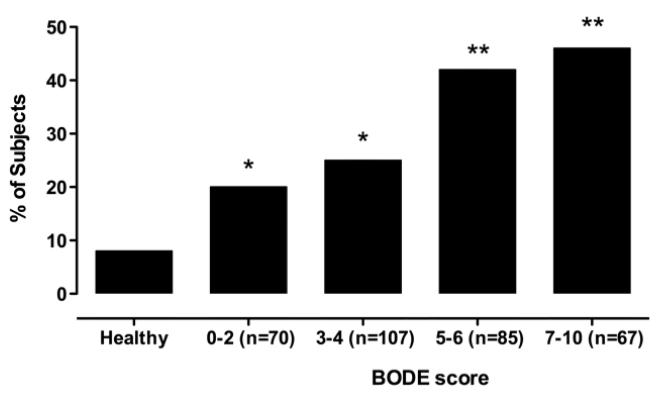

26% of Dutch patients with mild breathlessness (MRC Dyspnoea Scores 1 or 2) demonstrated quadriceps weakness (Figure 2). The highest prevalence of weakness was observed in subjects with the most severe dyspnoea (MRC dyspnoea score 4 or 5). The odds-ratio (OR) for quadriceps weakness among MRC dyspnoea scores of 4 or 5 compared to scores of 1, 2 or 3, was 2.46 (95%CI: 1.54 to 3.94, p<0.001). When adjusted for the severity of airflow obstruction, the presence of severe dyspnoea (MRC scores 4 or 5) remained an independent predictor of quadriceps weakness in the Dutch cohort (OR 2.21; 95% CI: 1.32 to 3.71, p=0.003). The prevalence of quadriceps weakness in the Dutch cohort divided according to the BODE quartiles previously reported by Celli et al (10), is illustrated in Figure 3. Quadriceps weakness was present in one-fifth of patients in the BODE quartile associated with the best prognosis (a BODE score of 0 to 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Relationship between weakness and exercise performance in Dutch patients

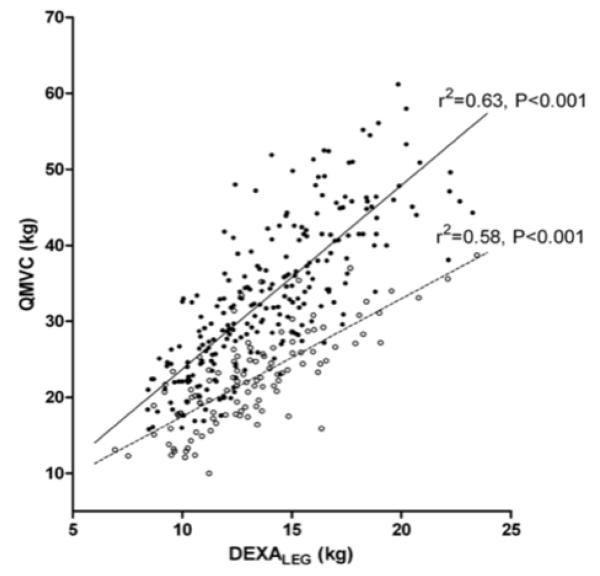

Table 4 compares Dutch COPD patients, with and without quadriceps weakness. FFM index was similar in both groups. Patients with quadriceps weakness had worse airflow obstruction (lower FEV1), increased hyperinflation (increased RV/TLC), reduced exercise capacity (as judged by the 6MWD) and impaired health-related quality of life (as determined by the SGRQ). Multiple linear regression analysis suggested that quadriceps weakness was associated with a reduction in 6MWD of 30m (95%CI: 8m to 52m, p=0.009), or Wpeak of 6W (95%CI: 1W to 11W, p=0.016), independent of the anthropomorphic variables related to these tests, FEV1 or RV/TLC. A diagnosis of quadriceps weakness was unsurprisingly associated with reduced lower-limb lean mass (DEXALEG), but also reduced QMVC (Figure 4) and TwQ per unit DEXALEG.

Table 4. Clinical characteristics of Dutch COPD patients with and without quadriceps weakness.

Values presented are mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. P-values were derived from ANOVA unless indicated.

| Normal QMVC (n=236) |

Weak QMVC (n=115) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 63 (9) | 63 (11) | 0.487 | |

| Sex (%male) | 56 | 59 | 0.647a | |

| FFMI (kg/m2) | 15.7 (2.1) | 15.8 (2.1) | 0.583 | |

|

| ||||

| DEXABODY LM (kg) | 45.6 (9.2) | 43.6 (8.7) | 0.057 | |

| DEXALEG LM (kg) | 14.1 (3.2) | 13.2 (3.0) | 0.013 | |

| QMVC/DEXALEG | 2.38 (0.43) | 1.71 (0.32) | <0.001 | |

| TwQ/DEXALEG | 0.56 (0.16) | 0.46 (0.14) | <0.001 | |

|

| ||||

| %predicted FEV1 (%) | 46.2 (18.2) | 40.6 (17.0) | 0.006 | |

| %predicted DLCO (%) | 51.3 (17.8) | 48.4 (18.7) | 0.237 | |

| RV/TLC (%) | 56.3 (10.8) | 59.7 (11.2) | 0.008 | |

| PaO2 (kPa) | 9.40 (1.36) | 9.21 (1.48) | 0.237 | |

| PaCO2 (kPa) | 5.29 (0.66) | 5.39 (0.76) | 0.192 | |

|

| ||||

| 6MWT (m) | 452 (119) | 403 (108) | <0.001 | |

| Wpeak (W) | 74(33) | 62(29) | 0.002 | |

|

| ||||

| SGRQ Score |

Total score | 52.8 (17.0) | 57.6 (16.0) | 0.018 |

| Symptoms | 60.2 (20.3) | 65.5 (19.5) | 0.033 | |

| Activities | 68.3 (19.4) | 74.1 (18.1) | 0.012 | |

| Impacts | 41.7 (18.9) | 45.8 (18.7) | 0.076 | |

Key:

indicates use of Fishers exact test

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; DLCO, diffusing factor for carbon monoxide; RV/TLC, residual volume to total lung capacity ratio; PaO2, peripheral oxygen content of arterial blood; FFM(I), fat-free mass (index); DEXABODY and DEXALEG, dual energy absorptiometry measurement of whole body and lower limb lean mass (LM); QMVC, isometric quadriceps maximum voluntary contraction force; TwQ, twitch quadriceps force following magnetic femoral nerve stimulation; 6MWD, six-minute walk test distance; Wpeak, peak exercise capacity measured by incremental cycle ergometry; SGRQ, St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (lower score denotes improvement).

Figure 4.

DISCUSSION

Using predicted values generated from a cohort of middle-aged and older individuals without spirometric evidence of airflow obstruction, quadriceps weakness was observed in approximately one-third of COPD patients accessing hospital outpatient services, in two European countries. Quadriceps weakness was demonstrated in approximately one-quarter of patients with only mild airflow obstruction (defined by the British Thoracic Society as an FEV1 > 50% (12), equivalent to GOLD Stage 1 or 2) or mild dyspnoea (MRC dyspnoea score of 1 or 2).

Critique of the method

The study was retrospective in design and the regression analyses derived using the healthy data would ideally be verified in a prospective cohort. Although participating centres employed common measurement protocols, they did not use extreme measures (e.g. transport of patients between centres as biological controls) to absolutely exclude measurement differences arising from technique or equipment. However, a similar prevalence of weakness was found in two large COPD cohorts from two countries, despite differences in age and sex distribution, suggesting that differences arising from measurement technique were small. Both age and sex were considered when predicting quadriceps strength in patients, and may contribute to the observed similarity.

Clearly additional factors exist that might determine quadriceps strength. For example, the age range of the healthy subjects was selected to be similar to that typically observed among patients presenting with COPD, however, the majority of women were likely to be post-menopausal. Whether the same predictive estimates extend to pre-menopausal women or younger men is unclear. Another obvious limitation of a retrospective study is that of the data available. Objective measurements of activity levels (e.g. using accelerometry) are relevant to lower limb strength, but were unknown. Cardiovascular comorbidity is common in COPD, and the absence of left ventricular dysfunction or occult peripheral vascular disease, was not definitively excluded in all patients. This could be more relevant to the Dutch clinical population than UK research participants, in whom clinically overt disease was excluded. Recruitment bias toward patients with weakness or low activity levels should be recognised, particularly among patients referred to a rehabilitation hospital. However, as previously noted, the observed prevalence of weakness was similar in the community dwelling UK patients, many of whom had already received pulmonary rehabilitation. Prospective data from community dwelling COPD patients in the community not previously known to hospital physicians is required in order to estimate the prevalence of quadriceps weakness in both primary and hospital care.

Significance of the findings

The prevalence of weakness in the absence of a severely reduced FEV1 warrants discussion, as does the observation that prior smoking history may be associated with quadriceps weakness in apparently healthy subjects without dyspnoea or airflow obstruction. Since reduced physical activity in general leads to muscle atrophy we suggest that some COPD patients may adopt a state of reduced activity before the onset of significant airflow obstruction or symptoms. This proposition is supported by the data of Watz and colleagues who, using objective activity monitoring, demonstrated that only 26% of their cohort classified as GOLD stage 1 had a physical activity level considered “active” among healthy subjects (33). Evidence that patients fail to adopt a high activity lifestyle for behavioural reasons may be inferred by a recent study reporting increased physical activity levels with prolonged rehabilitation, without further gains in quadriceps strength, (the latter typically achieved over a shorter time frame) (34).

The second hypothesis is that cigarette smoking itself causes skeletal muscle disease, which in turn causes reduced physical activity. A direct effect of cigarette smoke has been suggested by studies that demonstrate increased quadriceps fatigue in young smokers (35, 36). Abnormalities have also been reported in muscle biopsies from the vastus lateralis of smokers without COPD (37). Interestingly, we could not detect an additional effect of current smoking status on strength in COPD in the present study.

Most studies investigating quadriceps strength have focused on cohorts of symptomatic, moderate-to-severe COPD patients. Although, as expected we found that increasing airflow obstruction classified by GOLD stage was associated with a trend toward a higher prevalence of quadriceps weakness, the association was not strong. The MRC scale describes dyspnoea in relation to general activity levels and its relationship with quadriceps weakness would tend to support a model whereby inactivity secondary to dyspnoea leads to muscle dysfunction. The contribution of dyspnoea appeared more predictive of quadriceps weakness than the degree of airflow obstruction.

Importantly a low fat-free mass index did not identify subjects at risk of quadriceps weakness, and comparable levels of BMI or FFMI were observed in COPD patients with or without weakness. A consensus on what constitutes a low fat-free mass index in middle-aged and elderly populations, and the significance of any differences between countries has yet to be established. Others have reported that the prevalence of lower limb muscle wasting exceeds that of whole body lean mass depletion (26, 38). The observation that quadriceps weakness in COPD occurs in the absence of FFM wasting suggests that such patients may benefit more from direct quadriceps intervention, such as pulmonary rehabilitation or neuromuscular electrical stimulation, than systemic anabolic therapies.

Whilst maximal muscle strength is commonly considered a function of available muscle mass, the Dutch cohort provided evidence that phenotypical quadriceps weakness is more complex then simple atrophy alone. QMVC normalised for lower-limb lean mass (DEXALEG) was reduced in weak subjects, suggesting that both quality, as well as quantity of muscle may be altered. A similar finding for TwQ normalised for DEXALEG suggests that quadriceps weakness is not merely a deficit of voluntary muscle activation. This finding is at variance with smaller studies reporting a close relationship between bulk and strength (17, 39), but is perhaps unsurprising given the larger sample reported. In one of these studies, QMVC normalised for mid-thigh thigh cross-sectional area measured by CT was reduced in subjects taking oral corticosteroids (39). No effect of oral steroids was observed in the Dutch cohort, or indeed in a previous study reported by our group (40).

Given that quadriceps strength can convey prognostic information in COPD, and is not always a direct surrogate of low BMI or vice-versa, QMVC may improve the prognostic power of indices such as the BODE score. In its original description, the BODE score was associated with a generalized r2 of only 0.21 for predicting death in COPD. One-fifth of COPD patients in the BODE quartile associated with the best prognosis demonstrated quadriceps weakness; it is unknown if such patients may be at additional risk.

Reduced quadriceps strength relates to increased mortality and reduced exercise capacity in COPD. Overt and undetected disease, represent a major public health challenge. This retrospective study demonstrates that quadriceps weakness is detectable in early disease as judged by predicted FEV1 or the MRC dyspnoea scale. Future studies of quadriceps function in community dwelling patients unknown to hospital services, and in apparently healthy ex-smokers are needed to determine how widely this observation can be generalised beyond secondary care. Detection of weakness could in theory be achieved alongside spirometry screening programmes. Pulmonary rehabilitation can ameliorate skeletal muscle strength in COPD, but has conventionally been reserved for symptomatic patients (MRC Scores of 3 or above) (12). It seems likely that patients with quadriceps weakness but only mild airflow obstruction may benefit from exercise-based training, although determining to optimal mode of delivery of such training to patients who may still be working or caring for family members may require innovative methodology.

In summary, we have derived a predictive equation for quadriceps strength from healthy subjects, that is suitable as a reference guide for patients with COPD, By applying this equation to two separate cohorts of COPD patients, we showed that approximately one quarter of patients with mild COPD had quadriceps weakness. We suggest that inactivity and quadriceps strength may be an early feature of COPD in some patients, and may be amenable to rehabilitation.

Funding Statement and Acknowledgements

JMS was funded by the British Lung Foundation, and an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline administered by the Royal Brompton Hospital, UK. NSH was funded by the Wellcome Trust UK and the ENIGMA in COPD Project (European Union). SAS was funded by the Wellcome Trust UK and an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. WD-CM was funded by the National Institute for Health (UK) Research Clinician Scientist Programme. AJ was funded by the Moulton Foundation. Part of this project was undertaken at the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit in Advanced Lung Disease at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London. MP's salary was part-funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit funding scheme. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, The National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. The authors wish to thank Jos Peeters and Linda Op het Veld for their assistance in collecting the Dutch cohort data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Skeletal muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A statement of the american thoracic society and european respiratory society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:S1-40. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.supplement_1.99titlepage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gosselink R, Troosters T, Decramer M. Peripheral muscle weakness contributes to exercise limitation in copd. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:976–980. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decramer M, Gosselink R, Troosters T, Verschueren M, Evers G. Muscle weakness is related to utilization of health care resources in copd patients. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:417–423. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10020417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swallow EB, Reyes D, Hopkinson NS, Man WD, Porcher R, Cetti EJ, Moore AJ, Moxham J, Polkey MI. Quadriceps strength predicts mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2007;62:115–120. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Man WD, Soliman MG, Nikoletou D, Harris ML, Rafferty GF, Mustfa N, Polkey MI, Moxham J. Non-volitional assessment of skeletal muscle strength in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2003;58:665–669. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.8.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gea JG, Pasto M, Carmona MA, Orozco-Levi M, Palomeque J, Broquetas J. Metabolic characteristics of the deltoid muscle in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:939–945. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17509390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polkey MI, Moxham J. Attacking the disease spiral in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Med. 2006;6:190–196. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-2-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Fairbairn AS, Wood CH. The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population. Br Med J. 1959;2:257–266. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5147.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spruit MA, Pennings HJ, Janssen PP, Does JD, Scroyen S, Akkermans MA, Mostert R, Wouters EF. Extra-pulmonary features in copd patients entering rehabilitation after stratification for mrc dyspnea grade. Respir Med. 2007;101:2454–2463. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson K, Killian K, McCartney N, Stubbing DG, Jones NL. Randomised controlled trial of weightlifting exercise in patients with chronic airflow limitation. Thorax. 1992;47:70–75. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulmonary rehabilitation survey: The British Thoracic Society & British Lung Foundation. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12.NICE Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National clinical guideline for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax. 2004;59(Suppl I) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swallow EB, Reyes D, Hopkinson NS, Man WD, Porcher R, Cetti EJ, Moore AJ, Moxham J, Polkey MI. Quadriceps strength predicts mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2007;62:115–120. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards RH, Young A, Hosking GP, Jones DA. Human skeletal muscle function: Description of tests and normal values. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;52:283–290. doi: 10.1042/cs0520283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decramer M, Lacquet LM, Fagard R, Rogiers P. Corticosteroids contribute to muscle weakness in chronic airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:11–16. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkinson NS, Nickol AH, Payne J, Hawe E, Man WD, Moxham J, Montgomery H, Polkey MI. Angiotensin converting enzyme genotype and strength in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:395–399. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-578OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seymour JM, Ward K, Sidhu PS, Puthucheary Z, Steier J, Jolley CJ, Rafferty G, Polkey MI, Moxham J. Ultrasound measurement of rectus femoris cross-sectional area and the relationship with quadriceps strength in copd. Thorax. 2009;64:418–423. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.103986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swallow EB, Barreiro E, Gosker H, Sathyapala SA, Sanchez F, Hopkinson NS, Moxham J, Schols A, Gea J, Polkey MI. Quadriceps muscle strength in scoliosis. Eur Respir J. 2009 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00074008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Gold executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, Pinto Plata V, Cabral HJ. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1005–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swallow EB, Gosker HR, Ward KA, Moore AJ, Dayer MJ, Hopkinson NS, Schols AM, Moxham J, Polkey MI. A novel technique for nonvolitional assessment of quadriceps muscle endurance in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:739–746. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00025.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiner MC, Barton RL, Singh SJ, Morgan MD. Bedside methods versus dual energy x-ray absorptiometry for body composition measurement in copd. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:626–631. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00279602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, Johnson DC, van der Grinten CP, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Enright P, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:720–735. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, Pedersen OF, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:511–522. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engelen MP, Schols AM, Does JD, Wouters EF. Skeletal muscle weakness is associated with wasting of extremity fat-free mass but not with airflow obstruction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:733–738. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.3.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polkey MI, Kyroussis D, Hamnegard CH, Mills GH, Green M, Moxham J. Quadriceps strength and fatigue assessed by magnetic stimulation of the femoral nerve in man. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:549–555. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199605)19:5<549::AID-MUS1>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ats statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mador MJ, Bozkanat E, Kufel TJ. Quadriceps fatigue after cycle exercise in patients with copd compared with healthy control subjects. Chest. 2003;123:1104–1111. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The st. George's respiratory questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1321–1327. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vestbo J, Prescott E, Almdal T, Dahl M, Nordestgaard BG, Andersen T, Sorensen TI, Lange P. Body mass, fat-free body mass, and prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from a random population sample: Findings from the copenhagen city heart study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:79–83. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-969OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schols A, Soeters PB, Dingemans AM, Mostert R, Frantzen PJ, Wouters EF. Prevalence and characteristics of nutritional depletion in patients with stable copd eligible for pulmonary rehabilitation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993:147. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.5.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watz H, Waschki B, Boehme C, Claussen M, Meyer T, Magnussen H. Extrapulmonary effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on physical activity: A cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:743–751. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1011OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS, Langer D, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Are patients with copd more active after pulmonary rehabilitation? Chest. 2008;134:273–280. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morse CI, Wust RC, Jones DA, de Haan A, Degens H. Muscle fatigue resistance during stimulated contractions is reduced in young male smokers. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;191:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wust RC, Morse CI, de Haan A, Rittweger J, Jones DA, Degens H. Skeletal muscle properties and fatigue resistance in relation to smoking history. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:103–110. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0792-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montes de Oca M, Loeb E, Torres SH, De Sanctis J, Hernandez N, Talamo C. Peripheral muscle alterations in non-copd smokers. Chest. 2008;133:13–18. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hopkinson NS, Tennant RC, Dayer MJ, Swallow EB, Hansel TT, Moxham J, Polkey MI. A prospective study of decline in fat free mass and skeletal muscle strength in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2007;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernard S, LeBlanc P, Whittom F, Carrier G, Jobin J, Belleau R, Maltais F. Peripheral muscle weakness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:629–634. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9711023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopkinson NS, Man WD, Dayer MJ, Ross ET, Nickol AH, Hart N, Moxham J, Polkey MI. Acute effect of oral steroids on muscle function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:137–142. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00139003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]