Abstract

Technical challenges have greatly impeded the investigation of membrane protein folding and unfolding. To develop a new tool that facilitates the study of membrane proteins, we tested pulse proteolysis as a probe for membrane protein unfolding. Pulse proteolysis is a method to monitor protein folding and unfolding, which exploits the significant difference in proteolytic susceptibility between folded and unfolded proteins. This method requires only a small amount of protein and in many cases may be used with unpurified proteins in cell lysates. To evaluate the effectiveness of pulse proteolysis as a probe for membrane protein unfolding, we chose H. halobium bacteriorhodopsin (bR) as a model system. The denaturation of bR in SDS has been investigated extensively by monitoring the change in the absorbance at 560 nm (A560). In this work we demonstrate that denaturation of bR by SDS results in a significant increase in its susceptibility to proteolysis by subtilisin. When pulse proteolysis was applied to bR incubated in varying concentrations of SDS, the remaining intact protein determined by electrophoresis shows a cooperative transition. The midpoint of the cooperative transition (Cm) shows excellent agreement with that determined by A560. The Cm values determined by pulse proteolysis for M56A and Y57A bR are also consistent with the measurements made by A560. Our results suggest that pulse proteolysis is a quantitative tool to probe membrane protein unfolding. Combining pulse proteolysis with western blotting may allow the investigation of membrane protein unfolding in situ without over-expression or purification.

Keywords: Bacteriorhodopsin, membrane proteins, protein folding, protein stability, pulse proteolysis

Introduction

Understanding how the sequence information of a protein encodes its three dimensional structure, often termed the protein folding problem, is one of the greatest challenges in science. Quantitative assessment of kinetics and thermodynamics of protein folding have been an essential component of the pursuit of this challenge. By investigating kinetics and thermodynamics of protein folding we have learned a great deal about the mechanistic details of protein folding and the forces stabilizing protein structures. Our understanding of membrane protein folding is, however, significantly underdeveloped relative to that of water soluble proteins.1-5 This disparity is mostly attributable to the technical difficulties of studying membrane proteins.

One of the common challenges researchers encounter in the investigation of membrane proteins is the difficulty in obtaining pure membrane protein in the quantity necessary for biophysical studies.6 Membrane proteins exist in an anisotropic environment composed of both aqueous and lipid solvents. Due to the difficulty in maintaining this complex solvent environment, purified integral membrane proteins tend to behave poorly in biophysical studies.7 Another common limitation to such investigations is that the lipids and detergents that are required to maintain folded membrane proteins may interfere with spectroscopic or calorimetric methods.8-10 Finally, the denatured states of integral membrane proteins may retain a significant amount of secondary and tertiary structure.11,12 Minimal difference in the signal of the native and denatured species may compromise the ability to monitor folding and unfolding of membrane proteins using common spectroscopic probes.13,14 As a result, many experimental methods developed to investigate folding of water-soluble proteins are often not so useful in the investigation of membrane protein folding. Novel conformational probes that may circumvent the current technical difficulties and complement existing techniques are needed to support the growing interest in membrane protein folding.15,16

To address the need for novel probes to investigate membrane protein folding, we tested the validity of pulse proteolysis as a probe of membrane protein folding. Pulse proteolysis is a method to determine the fraction of native protein (fN) with a short pulse of proteolysis.17,18 Folded and unfolded proteins typically have very distinct preoteolytic susceptibility. Thus, one can determine fN by quantifying the amount of intact protein remaining after unfolded proteins are selectively digested by pulse proteolysis. We have shown that pulse proteolysis is a robust and versatile method to measure thermodynamic stability as well as unfolding kinetics of soluble proteins.17,18 Pulse proteolysis requires much less protein than conventional approaches. Determination of thermodynamic stability is possible with less than 100 μg of protein. Also, the use of gel electrophoresis for quantification of remaining intact protein eliminates the need to purify a protein for folding studies. Furthermore, by coupling pulse proteolysis to quantitative western blotting (Pulse and Western), folding and unfolding of low abundance proteins can be studied in a cell lysate.19 These merits of pulse proteolysis may be particularly useful in the investigation of membrane proteins, which are typically difficult to express and purify. Also, because pulse proteolysis does not rely on spectroscopic properties of proteins, the method may be applicable even when unfolding does not result in significant changes in spectroscopic signals or when lipids or detergents interfere with the measurement.

To test the applicability of pulse proteolysis to membrane protein folding studies, we chose H. halobium bacteriorhodopsin (bR), a seven-helical transmembrane protein, as a model. Because bR has a retinal cofactor, the structural integrity of the protein can be monitored easily by the absorbance at 560 nm (A560). Due to this convenient probe and the relatively easy purification of the protein, bR has been a popular model system for membrane protein folding studies. Moreover, it has been shown that unfolding of bR by SDS is reversible20 and that the free energy of unfolding (ΔGunf) of bR in the transition zone is linearly proportional to mole fraction of SDS (XSDS) in mixed micelles.21,22 This empirical relationship makes bR a valuable system to investigate energetic principles governing thermodynamic stability of membrane proteins. Furthermore, kinetic analysis of bR folding and unfolding in mixed micelles with varying XSDS shows that bR demonstrates simple two-state folding behavior.22 This two-state behavior has also lead to the characterization of the folding transition state of bR using Φ-value analysis.23 The great deal of information on the thermodynamic stability and folding/unfolding kinetics of bR makes this protein an ideal model to test the validity of pulse proteolysis as a probe for unfolding of membrane proteins. Here we report our successful application of pulse proteolysis to monitor the denaturation of bR in a quantitative manner. To assess the accuracy of the method, we compared fN determined by pulse proteolysis with fN determined by A560. We also demonstrate that pulse proteolysis is a valid tool to determine the effect of mutations on the membrane protein stability by applying pulse proteolysis to two variants of bR.

Subtilisin is a suitable protease for pulse proteolysis in SDS

To test the validity of pulse proteolysis as a probe for bR denaturation in SDS, it was necessary to ensure that proteolytic activity is maintained in the presence of SDS. Pulse proteolysis of soluble proteins typically uses thermolysin to digest unfolded protein in urea.17,24 However, we find that thermolysin is rapidly inactivated by SDS (data not shown). This inactivation seems to result from precipitation of SDS and Ca2+, which is an essential metal ion for the structural integrity of thermolysin. We therefore tested subtilisin, another robust bacterial protease with broad specificity. It has been reported that subtilisin retains its structure in the presence of SDS.25

To determine whether subtilisin is active enough for pulse proteolysis in SDS, we evaluated the enzyme activity under the conditions used for the denaturation of bR. Unfolding of bR is typically investigated by titrating bR in lipid bicelles composed of DMPC, a saturated lipid, and CHAPSO, a non-denaturing detergent, with SDS.21 The activity of subtilisin was determined by measuring the rate of the cleavage of a fluorogenic substrate, ABZ-Ala-Gly-Leu-Ala-NBA, by subtilisin in the presence of 15 mM DMPC, 16 mM CHAPSO, and varying concentrations of SDS. The increase in fluorescence from the cleavage of the substrate fit well to a first-order rate equation at all concentrations of SDS tested, which indicates subtilisin is not inactivated during the assays. Still, our assay show that the kcat/Km value decreases as SDS concentration is increased (Supplementary Figure S1). The apparent inhibition of subtilisin by SDS has been previously explained by the partitioning of peptide substrates into SDS micelles.25 Nevertheless, subtilisin retains enough catalytic activity for pulse proteolysis even when the mole fraction of SDS in mixed micelles (XSDS) is 0.85, which is significantly higher than the known Cm value of bR (XSDS = 0.72) under the same condition.22 This result suggests that subtilisin is a suitable protease for pulse proteolysis in the presence of SDS.

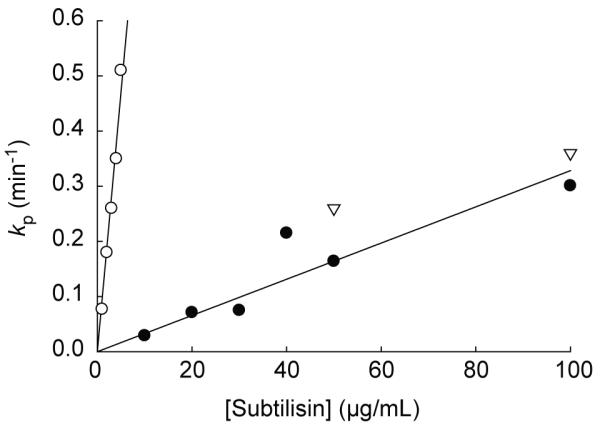

Denaturation by SDS significantly increases the proteolytic susceptibility of bacteriorhodopsin

In order for pulse proteolysis to serve as a valid probe of bR unfolding, the SDS-denatured state must be significantly more susceptible to proteolysis than the native state. In the case of bR, it is known that the SDS-denatured species primarily exists within the membrane and retains about 40% α-helical content.13,14 To determine whether native and SDS-denatured bR have distinct proteolytic susceptibility, we measured the rate of proteolysis at XSDS = 0.60 and XSDS = 0.83 at which bR is native and denatured, respectively.22 The disappearance of intact bR by proteolysis fit well to a first-order rate equation under all conditions. To determine kcat/Km reliably and to learn the nature of the rate-limiting step for proteolysis, we determined the proteolysis rate of bR with different concentrations of subtilisin (Figure 1). The apparent kcat/Km values for SDS-denatured bR (43000 ± 2000 M−1s−1) is about 30-fold greater than that for native bR (1500 ± 100 M−1s−1). This result clearly demonstrates that SDS-denatured state of bR is more proteolytically susceptible than native bR. When estimated with these kinetic constants, ~85% of native bR and less than 1% of SDS-denatured bR would remain intact after 1-min pulse with 50 μg/mL subtilisin. Also, the linear correlation between the proteolysis rate and the protease concentration suggests that the proteolysis step catalyzed by the enzyme, not the preceding conformational change in bR, is the rate-limiting step for the overall proteolysis.26

Figure 1. Kinetics of proteolysis of wild-type bacteriorhodopsin by subtilisin.

Kinetics of proteolysis of bR by subtilisin was determined under a native condition at 0.60 XSDS (●), an SDS-denaturing condition at 0.83 XSDS (○), and at 0.75 XSDS, the observed Cm by pulse proteolysis (▽). bR was pre-equilibrated in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 15 mM DMPC, 16 mM CHAPSO for at least 1 hr. bR was then diluted into the same buffer containing the designated XSDS to a final protein concentration of 0.10 mg/ml and allowed to equilibrate for 3 min. Following the equilibration, varying concentrations of subtilisin were added to each reaction. Reactions were quenched by the addition of PMSF to the final concentration of 13 mM at designated time points. The kinetic constants (kp) were determined by fitting the disappearance of intact bR over time on an SDS-PAGE gel to a first-order rate equation. The kcat/Km values at 0.60 XSDS and 0.83 XSDS were determined from the slope of the plots.

Though the sequences of the cleavage sites in bR are different from that of the peptide substrate, the comparison of the kcat/Km values for bR with those for the peptide substrate provides valuable insight into the conformations of native and SDS-denatured bR. At XSDS =0.53, a condition similar to the condition chosen for native bR proteolysis measurements (XSDS =0.60), the kcat/Km value of the fluorogenic tetrapeptide substrate is 27000 M−1s−1, which is about 20-fold greater than that of native bR (1500 ± 100 M−1s−1). Thus, native bR is significantly less susceptible than the peptide substrate. This is presumably because bR is structured and exists exclusively within mixed micelles or because the sequence of the cleavage site in bR is not as favorable as the peptide substrate for subtilisin. Interestingly, under denaturing conditions (0.82 XSDS), the kcat/Km of the peptide substrate is 1400 M−1s−1, which is about 30-fold lower than the kcat/Km of SDS-denatured bR (43000 ± 2000 M−1s−1). When it is considered that bR may have less favorable cleavage sequences than the peptide substrate, the greater susceptibility of SDS-denatured bR than that of the peptide substrate is intriguing. Under this condition it is likely that the peptide substrate is mostly partitioned into the micelles, but SDS-denatured bR contains solvent-accessible unstructured loops that are easily cleavable by the protease.

The nature of the SDS-denatured state of bR remains a subject of some controversy. The loss of the absorbance at 560 nm (A560) upon denaturation by SDS suggests a drastic change in the microenvironment around the bound retinal. Interpretation of the circular dichroism spectra suggested the SDS-denatured state of bR has about 40% less helical content than native bR.14 However, based on disagreement between α-helical content as determined by CD and NMR for several proteins in the presence of SDS, it has been suggested that there is not sufficient evidence for a loss of secondary structure in the SDS-denatured state of bR.10 It is noteworthy that the increased proteolytic susceptibility of SDS-denatured bR relative to that of native bR is consistent with the observed loss of structure in the SDS-denatured state. More recently, hydrogen-deuterium exchange as well as oxidative methionine labeling suggests that SDS-denatured bR contains several unstructured regions,11,12 which is also consistent with our observation.

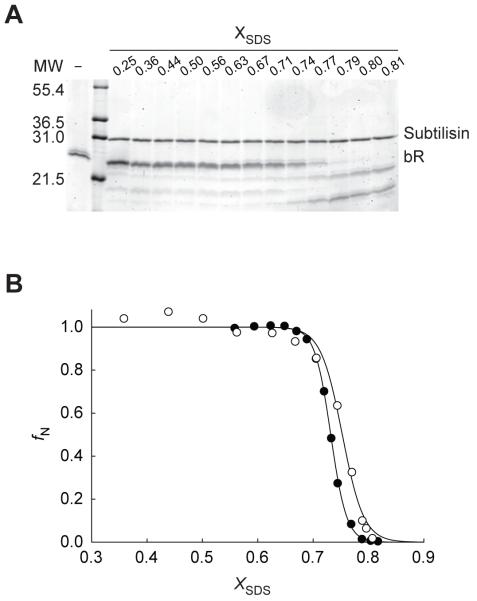

Pulse proteolysis reports a cooperative unfolding transition of bacteriorhodopsin in SDS

The validity of pulse proteolysis as a probe for bR unfolding was assessed by comparison to A560. Pulse proteolysis was performed under the experimental conditions previously designed to monitor bR unfolding by A560.21 After 3-min equilibration of bR in solutions with varying XSDS, each sample was incubated with 50 μg/mL subtilisin for 1 min. According to the proteolysis kinetics discussed above, 1-min incubation with this concentration of subtilisin ensures nearly complete digestion of SDS-denatured bR while minimizing the digestion of the native bR. The remaining intact bR in each sample after pulse proteolysis was analyzed by SDS PAGE (Figure 2A). The majority of bR remains intact following pulse proteolysis under native conditions (XSDS < 0.70), which is consistent with the proteolysis kinetics discussed above. Complete digestion of unfolded bR at XSDS = 0.81 confirms that subtilisin retains sufficient activity in SDS for pulse proteolysis. Also, proteolysis of native and SDS-denatured bR species show distinct cleavage patterns, producing three and two discernable cleavage products respectively. This difference in cleavage patterns further confirms that bR experiences a significant conformational change upon denaturation by SDS.

Figure 2. Pulse proteolysis of wild-type bacteriorhodopsin.

(A) A representative SDS-PAGE gel following pulse proteolysis of bR is shown. bR was pre-equilibrated in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 15 mM DMPC, 16 mM CHAPSO for at least 1 hr. bR was then diluted into the same buffer containing varying concentrations of SDS. Reactions were incubated for 3 min before the initiation of pulse proteolysis by the addition of subtilisin to 50 μg/mL. After 1 min, reactions were quenched by the addition of PMSF to 10 mM. Quenched reactions were then analyzed by SDS PAGE. Undigested bR (−) is shown for comparison. (B) fN of wild-type bR in SDS was determined by pulse proteolysis (○) and by A560 (●). The fN values were determined from pulse proteolysis by dividing the remaining intact bR intensities by the intensity of the upper baseline (I0) value derived from the fitting of the data set to the two-state equilibrium unfolding model. Equilibrium unfolding of bR was monitored by A560 as previously described.21 Briefly, bR was pre-equilibrated in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing15 mM DMPC, 16 mM CHAPSO for at least 1 hr. bR was then diluted into the same buffer to a final concentration of 0.10 mg/mL. The protein was titrated with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 20% SDS, 15 mM DMPC, 16 mM CHAPSO, to raise the XSDS. Following each addition of the solution, the reaction was stirred for 3 min in the dark before the A560 was read. Data was fit to a two-state equilibrium unfolding model. The XSDS at which half of the protein is denatured (Cm) determined by pulse proteolysis and A560 are 0.753 ± 0.003 XSDS and 0.732 ± 0.001 XSDS, respectively.

The plot of normalized band intensities of intact bR versus XSDS shows a cooperative transition (Figure 2B). The transition midpoint (Cm) value of 0.753 ± 0.003 XSDS was determined by fitting the plot to a two-state equilibrium unfolding model. The average Cm values of wild-type bR determined in triplicate experiments was 0.749 ± 0.005 XSDS. These results demonstrate that Cm determination by pulse proteolysis has good precision. For comparison, unfolding of bR under the identical condition was also monitored with A560 as described previously21 (Figure 2B). The transition monitored by A560 is very similar to the transition monitored by pulse proteolysis; The Cm value determined by A560 (0.732 ± 0.001 XSDS) is in good agreement with the Cm value determined by pulse proteolysis. The coincidental change in proteolytic susceptibility and the disruption of the retinal binding site suggests that the denaturation of bR by SDS is cooperative.

A key assumption in the application of pulse proteolysis is that the amount of native protein that is digested during the reaction is negligable.17,24 However, the observed rate of proteolysis of native bR at XSDS= 0.60 (Figure 1) indicates that about 15% of folded bR is digested during 1-min pulse with 50 μg/mL subtilisin. To estimate the experimental error in Cm introduced by the proteolysis of native bR, we repeated pulse proteolysis with higher concentrations of subtilisin (100 and 200 μg/mL). The amount of the remaining intact bR after pulse proteolysis was clearly lower when higher concentrations of subtilisin were used (Data not shown). However, the Cm values were not affected significantly; the Cm values determined with 100 and 200 μg/mL subtilisin were 0.756 ± 0.003 XSDS and 0.754 ± 0.008 XSDS, respectively. This result demonstrates that Cm determination of wild-type bR is not affected by the proteolysis of native bR. One possible explanation for the independence of the Cm value on the concentration of subtilisin used in the pulse is that similar fractions of native bR are digested at different XSDS. To test this possibility, the proteolysis rate of native bR at XSDS = 0.75, the observed Cm value, was measured in the presence of 50 and 100 μg/mL subtilisin. The observed rate constants at 0.75 XSDS are close to those observed at 0.60 XSDS (Figure 1). This result suggests that the proteolysis rate of native bR is somewhat independent of XSDS, which is also consistent with the flat upper baseline of the normalized band intensity versus XSDS plot (Figure 2B). The similar proteolysis rates of native bR seem to result in a uniform decrease in band intensities and consistent Cm values that are independent of protease concentration. Therefore, the proteolysis of native bR during a pulse does not cause any systematic error in Cm determination. It is also notable that SDS does not affect the rate of proteolysis of native bR by subtilisin but does affect that of the peptide substrate. This difference is again consistent with the suggestion that the decrease of subtilisin activity at higher SDS concentration is not from inhibition of subtilisin by SDS but from the partitioning of soluble substrate into SDS micelles.25 The rate of proteolysis of bR by subtilisin is likely to be independent of SDS concentration simply because bR does not experience a significant change in its distribution between the soluble phase and the mixed micelle phase.

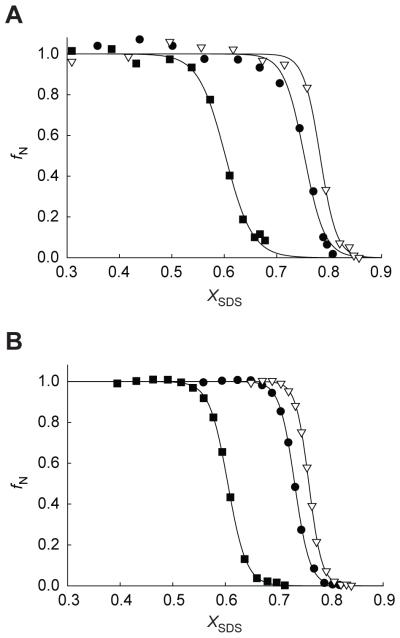

To demonstrate that pulse proteolysis is capable of detecting changes in membrane protein stability, we characterized M56A and Y57A bRs, which have previously shown to be more stable and less stable variants, respectively, relative to wild-type bR.21 Pulse proteolysis of M56A and Y57A bRs was performed in varying XSDS with 50 μg/mL subtilisin as described above (Figure 3A). Denaturation of the two variants by SDS was also characterized using A560 for comparison (Figure 3B). The observed Cm values are reported in Table 1. The change in the Cm value relative to wild-type (ΔCm) by pulse proteolysis are consistent with ΔCm as determined by A560 measurements for both bR point mutants. This result demonstrates that pulse proteolysis is an efficient and reliable tool to monitor the variation in membrane protein stability.

Figure 3. Effect of mutations on the denaturation of bR by SDS monitored by pulse proteolysis and A560.

Denaturation of wild-type (●), M56A (▽), and Y57A (■) bR by SDS was monitored by pulse proteolysis and A560. (A) Pulse proteolysis was performed for M56A and Y57A bR as described in Figure 2. Quenched reactions were then analyzed by SDS PAGE. The intensity of remaining mutant bR after pulse proteolysis is converted to fN and plotted against XSDS for each reaction. (B) The A560 values of bR were also converted to fN and plotted against XSDS. Reactions were performed as described in Figure 2. Wild-type bR data are shown for comparison.

Table 1.

Cm values of wild-type, M56A, and Y57A bacteriorhodopsin determined by pulse proteolysis and by A560

| Bacteriorhodopisn | Pulse Proteolysis | A560 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cm* (XSDS) |

ΔCm† (XSDS) |

Cm* (XSDS) |

ΔCm† (XSDS) |

|

| Wild type | 0.753 ± 0.003 | - | 0.732 ± 0.001 | - |

| M56A | 0.783 ± 0.002 | 0.034 ± 0.005 | 0.759 ± 0.001 | 0.027 ± 0.001 |

| Y57A | 0.602 ± 0.003 | −0.147 ± 0.004 | 0.605 ± 0.001 | −0.127 ± 0.001 |

Cm values (± SE) were determined by fitting the band intensities at different XSDS to a two-state equilibrium unfolding model. Cm values of wild-type bR determined by pulse proteolysis in triplicate measurements have a standard deviation of 0.005 XSDS.

ΔCm = Cm (mutant) − Cm (wild type)

Pulse proteolysis as a probe for membrane protein folding

This work demonstrates that pulse proteolysis is an effective tool to monitor denaturation of a membrane protein in a quantitative manner. Though pulse proteolysis was originally developed to study folding and unfolding of soluble proteins in urea, this simple but quantitative method seems to be particularly useful in the investigation of membrane proteins. We have recently shown that the stability of low-abundance proteins can be determined in a cell lysate by combining pulse proteolysis with quantitative western blotting.19 Our successful application of pulse proteolysis to bR suggests that, if an antibody is available for a membrane protein, folding and unfolding of that protein may be investigated by this approach without overexpression or purification.

Additionally, it is known that in several cases the denatured state of a membrane protein may contain a significant amount of structure which may complicate spectroscopic differentiation of native and denatured species.13,14,27 In this work we have demonstrated that proteolysis is a sensitive probe that can distinguish between the native and denatured states of a membrane protein, regardless of their optical properties. It is also noteworthy that CHAPSO is known to complicate the use of far-UV CD as a probe because of the absorbance of its amide group.9 We show here that pulse proteolysis is not prohibited by the presence of DMPC, CHAPSO, and up to 5% (w/v) SDS. Thus, pulse proteolysis must be useful in the investigation of the folding of various membrane proteins that are challenging to study with spectroscopic methods.

Though pulse proteolysis can accurately determine Cm values, the method does not report accurate m-values, which is the dependence of ΔGunf° on the concentration of denaturant and a necessary parameter to determine ΔGunf°. Even with sophisticated biophysical measurements, m-values are known to be difficult to determine accurately. The intrinsic errors from quantification from SDS PAGE gels and the limited number of data points make the determination of m-values by pulse proteolysis impractical. For this reason, to determine ΔGunf° for soluble proteins by pulse proteolysis, the m-values were estimated from the size of the protein, based on the known statistical relationship.28 Unfortunately, there is no empirical way to estimate m-values for membrane proteins. Without m-values, Cm values (or ΔCm) cannot be converted to ΔGunf° (or ΔΔGunf°). Still, Cm values are valuable in comparing the effect of mutation on the stability of proteins, as melting temperatures (Tm) are frequently used. Another potential application of Cm determination by pulse proteolysis is the monitoring of ligand binding to a membrane protein. A significant number of membrane proteins are hormone receptors and drug targets. Ligand binding to the native conformation will stabilize proteins, which results in an increase of Cm. Therefore, Cm determination by pulse proteolysis in the presence of various ligands may be a convenient way to compare the affinity of ligands to a membrane protein in a quantitative manner. The application of pulse proteolysis as a tool to monitor ligand binding to membrane proteins is currently being developed in our laboratory.

Proteins frequently lose their activities due to the destabilizing effect of mutations far from their active sites. This is also common in mutations in integral membrane proteins that are known to be linked to human diseases.29 The root of these dysfunctions stems from compromised stability rather than the disruption of the functional sites in the folded protein. Experimental means to assess the destabilizing effect of the mutations are essential to decipher the molecular basis of these diseases. Pulse proteolysis coupled to western blotting can be an innovative approach to evaluate the effects of pathogenic mutations on the stability of endogenous or transiently-expressed membrane proteins in cell lysates without purification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Pei-Fen Liu and Joseph R. Kasper for helpful comments on this manuscript. The work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM063919 (J.U.B.).

Abbreviations used

- ABZ-

o-aminobenzoyl-

- A560

absorbance at 560 nm

- bR

H. halobium bacteriorhodopsin

- CHAPSO

3-([3-cholamidopropyl]dimethylammonio)-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate

- DMPC

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- NBA

p-nitrobenzylamide

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Present Address: M.-S. Kim, Genome Center and Department of Pharmacology, 451 Health Sciences Drive, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; N. H. Joh, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104

References

- 1.Bowie JU. Solving the membrane protein folding problem. Nature. 2005;438:581–589. doi: 10.1038/nature04395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oberai A, Ihm Y, Kim S, Bowie JU. A limited universe of membrane protein families and folds. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1723–1734. doi: 10.1110/ps.062109706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanley AM, Fleming KG. The process of folding proteins into membranes: Challenges and progress. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;469:46–66. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White SH. Biophysical dissection of membrane proteins. Nature. 2009;459:344–346. doi: 10.1038/nature08142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth PJ, Curnow P. Membrane proteins shape up: Understanding in vitro folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seddon AM, Curnow P, Booth PJ. Membrane proteins, lipids and detergents: Not just a soap opera. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Booth PJ, Curnow P. Folding scene investigation: Membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace BA, Teeters CL. Differential absorption flattening optical effects are significant in the circular dichroism spectra of large membrane fragments. Biochemistry. 1987;26:65–70. doi: 10.1021/bi00375a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brouillette CG, McMichens RB, Stern LJ, Khorana HG. Structure and thermal stability of monomeric bacteriorhodopsin in mixed phospholipid/detergent micelles. Proteins. 1989;5:38–46. doi: 10.1002/prot.340050106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renthal R. An unfolding story of helical transmembrane proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14559–14566. doi: 10.1021/bi0620454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joh NH, Min A, Faham S, Whitelegge JP, Yang D, Woods VL, Bowie JU. Modest stabilization by most hydrogen-bonded side-chain interactions in membrane proteins. Nature. 2008;453:1266–1270. doi: 10.1038/nature06977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan Y, Brown L, Konermann L. Mapping the structure of an integral membrane protein under semi-denaturing conditions by laser-induced oxidative labeling and mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;394:968–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.London E, Khorana HG. Denaturation and renaturation of bacteriorhodopsin in detergents and lipid-detergent mixtures. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:7003–7011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riley ML, Wallace BA, Flitsch SL, Booth PJ. Slow α helix formation during folding of a membrane protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:192–196. doi: 10.1021/bi962199r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong H, Joh NH, Bowie JU, Tamm LK. Methods for measuring the thermodynamic stability of membrane proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2009;455:213–236. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackenzie KR. Folding and stability of α-helical integral membrane proteins. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1931–1977. doi: 10.1021/cr0404388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park C, Marqusee S. Pulse proteolysis: A simple method for quantitative determination of protein stability and ligand binding. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nmeth740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Na Y-R, Park C. Investigating protein unfolding kinetics by pulse proteolysis. Protein Sci. 2009;18:268–276. doi: 10.1002/pro.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim M-S, Song J, Park C. Determination of protein stability in cell lysates by pulse proteolysis and Western blotting. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1051–1059. doi: 10.1002/pro.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen GQ, Gouaux E. Probing the folding and unfolding of wild-type and mutant forms of bacteriorhodopsin in micellar solutions: Evaluation of reversible unfolding conditions. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15380–15387. doi: 10.1021/bi9909039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faham S, Yang D, Bare E, Yohannan S, Whitelegge JP, Bowie JU. Side-chain contributions to membrane protein structure and stability. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curnow P, Booth PJ. Combined kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of α-helical membrane protein unfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:18970–18975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705067104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curnow P, Booth PJ. The transition state for integral membrane protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:773–778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806953106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park C, Marqusee S. Quantitative determination of protein stability and ligand binding by pulse proteolysis. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 2006 doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps2011s46. Unit 20.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw AK, Pal SK. Activity of Subtilisin Carlsberg in macromolecular crowding. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2007;86:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park C, Marqusee S. Probing the high energy states in proteins by proteolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:1467–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau FW, Bowie JU. A method for assessing the stability of a membrane protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5884–5892. doi: 10.1021/bi963095j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers JK, Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: Relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2138–2148. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders CR, Myers JK. Disease-related misassembly of membrane proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2004;33:25–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.140348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.