Abstract

The tip-growing pollen tube is a useful model for studying polarized cell growth in plants. We previously characterized LePRK2, a pollen-specific receptor-like kinase from tomato (1). Here, we showed that LePRK2 is present as multiple phosphorylated isoforms in mature pollen membranes. Using comparative sequence analysis and phosphorylation site prediction programs, we identified two putative phosphorylation motifs in the cytoplasmic juxtamembrane (JM) domain. Site-directed mutagenesis in these motifs, followed by transient overexpression in tobacco pollen, showed that both motifs have opposite effects in regulating pollen tube length. Relative to LePRK2-eGFP pollen tubes, alanine substitutions in residues of motif I, Ser277/Ser279/Ser282, resulted in longer pollen tubes, but alanine substitutions in motif II, Ser304/Ser307/Thr308, resulted in shorter tubes. In contrast, phosphomimicking aspartic substitutions at these residues gave reciprocal results, that is, shorter tubes with mutations in motif I and longer tubes with mutations in motif II. We conclude that the length of pollen tubes can be negatively and positively regulated by phosphorylation of residues in motif I and II respectively. We also showed that LePRK2-eGFP significantly decreased pollen tube length and increased pollen tube tip width, relative to eGFP tubes. The kinase activity of LePRK2 was relevant for this phenotype because tubes that expressed a mutation in a lysine essential for kinase activity showed the same length and width as the eGFP control. Taken together, these results suggest that LePRK2 may have a central role in pollen tube growth through regulation of its own phosphorylation status.

Keywords: Microfilaments, Mutagenesis Mechanisms, Phosphorylation Enzymes, Receptor Serine Threonine Kinase, Signal Transduction, Juxtamembrane Domain, Pollen Tube Growth, Pollination, Site-directed Mutagenesis, Tomato

Introduction

Polarized cell growth in plants is essential for fertilization. When a pollen grain lands on the stigma, the pollen tube emerges, grows through the female tissue, and delivers the sperm cells to the ovule (2). Pollen tubes display an organelle-deprived tip, a subapical region where cytoplasmic streaming changes directions and organelles bounce back to the shank of the tube, and a nuclear and vacuolar zone that restricts metabolic processes to the most apical region of the tube. Actin polymerization plays a central role in the control of pollen tube growth (3), where its inhibition or activation profoundly affects tube growth (4).

Cell surface receptor kinases activate signal transduction pathways upon perception of extracellular signals, mediating cellular responses to the environment and to neighbor cells (5). LePRK1 and LePRK2 are two leucine rich repeat-receptor like kinases specifically expressed in pollen of Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) (6). LePRK2 is localized at the plasma membrane of the pollen tube and is part of a high molecular weight protein complex (LePRK complex) (1). In LePRK2 antisense plants, pollen tube growth rate is reduced (7). LePRK2 possibly functions as a bridge to transduce signals from extracellular components into the cytoplasm through interaction with pollen cytoplasmic components such as KPP, an Rho of plants-guanine nucleotide exchange factor cytoplasmic protein that interacts with LePRK2 (8). This interaction suggested an association between LePRK2 and the modulation of Rho of plants activities critically important for pollen tube growth (9). Overexpression of a nearly full-length KPP caused depolarized tube growth and an aberrant arrangement of the actin cytoskeleton similar to the phenotypes seen when either wild type (wt) or constitutively active Rho of plants/RACs are overexpressed in pollen (10, 11). Pollen tubes that transiently overexpress LePRK2 had wide tips, whereas tubes co-expressing LePRK2 and KPP showed wider tips (7).

Protein phosphorylation is one of the most important post-translational modifications. LePRK2 is phosphorylated in mature and germinated pollen and specifically dephosphorylated when incubated with a peculiar component of the style (12). The identification of the specific phosphorylation sites of the kinases involved as well as their substrates are the keys to a molecular understanding of signaling within cells. A suitable approach to understand the complexity of cell regulation is to study how a cellular process is regulated by modifying phosphorylated residues of phosphoproteins. For example, alanine substitution of three serines in the JM4 domain of XA21 modified the function of this disease resistance protein (13). Using comparative sequence analysis, modeling, and phosphorylation site prediction, two functional phosphorylation sites of the nodule autoregulation receptor kinase kinase catalytic domain from soybean were identified (14). It was also shown that several phosphorylated residues in JM domain of the receptor kinase BRI1 play a role in Brassinosteroid signaling (15–17).

Understanding phosphorylation in LePRK2 and its involvement in pollen tube growth is crucial for the comprehension of cell signaling during pollination events. Here, we mutated several potential phosphorylation residues of LePRK2 and analyzed the effects of these mutations on pollen tube growth. Our findings show that two potentially phosphorylated motifs in the JM domain of LePRK2 affect pollen tube length in contrasting ways. We also show that a mutant version of LePRK2 (mLePRK2), where the Lys372 residue in the subdomain II was mutagenized, alleviated the isotropic growth of pollen tubes and the abnormal actin deposition caused by LePRK2 overexpression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Two-dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

Germinated and mature tomato pollen protein extraction was as described (6). First dimension gels (7-cm strips, pH 4–7) were run in an Ettan IPGphor 3 IEF System (GE Healthcare) at 20 °C with steps of 500 V for 30 min, 1000 V for 30 min, and 5000 V for 1 h 40 min until 8200 Vh were reached. After the separation, strips were washed with 4 ml of equilibration buffer (EB; 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 6 m urea, 30% glycerol, 2% SDS, and 0.01% bromphenol blue) and 40 mg of DTT during 1 h at room temperature. Immediately, gels were incubated with 4 ml of EB with 225 mg of iodoacetamide. Gels were washed in running Tris-glycine buffer with 0.2% SDS, placed on top of the stacking gel, and covered with a layer of 0.5% agarose in running buffer. SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting were performed as described (1). The phosphorylation assay with [γ- 32P]ATP was as described (6). The entire reaction was loaded on a two-dimensional gel, blotted to nitrocellulose and exposed with a PhosphoImager Storm 820 (Molecular Dynamics). Style interactor for LePRKs was purified as described previously (12).

DNA Manipulation and Plasmids

LePRK2 and all LePRK2 mutant constructs were fused to eGFP under the control of the pollen-specific LAT52 promoter (pLAT52) (18) that confers constitutive expression in pollen grains and tubes. LAT52-eGFP was used as a control. For co-bombardment experiments, pLAT52-mRFP-mTalin was used (7). For mutagenesis, the QuikChange II-E Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used. Primers are listed in supplemental Table 1. All constructs were transiently expressed in tobacco pollen using a biolistic approach (18), and the length of the tubes and the width of the tubes tip were measured with ImageJ software (19). ClustalX (20) was used for sequence alignments. MEME (21) was used for discovering motifs. NetPhos (version 2.0) was carried out according to Ref. 22. GPS 2.0 was used as described (23).

Pollen Germination and Particle Bombardment-mediated Transient Expression in Tobacco Pollen

Tobacco pollen bombardment was carried out as described (7). Gold particles (3 mg; 1.0 μm diameter) were coated with 15 μg of DNA. For co-bombardment experiments, 3 mg of particles were coated with 15 μg of each DNA. Bombarded pollen was germinated in 500 μl of tomato pollen germination medium (6) in a 24-well plate and rocked at room temperature at 60 rpm. All analyses were done at 10 h of germination unless stated otherwise. Pollen tubes were imaged with an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus). Transfected and nontransfected pollen tubes from the same bombarded sample were individually measured with the same instrument settings. Using ImageJ, pollen tube length was determined measuring the distance from the end of the grain to the extreme of the tip. Pollen tube tip width was calculated by measuring the diameter of the widest region of the tip. Fluorescence intensities of pollen tube tips were measured using ImageJ in arbitrary units. GFP fluorescence intensity was defined as the difference in fluorescence intensities between transfected and nontransfected pollen tube tips. Expression levels of eGFP were classified as low (0–25 arbitrary units) or high (>25 arbitrary units). To study the effects of the different phosphorylation mutants on pollen tube growth, we analyzed pollen tubes with low fluorescence levels as it was described previously (24, 25). Pollen widths and lengths were classified in these groups depending on their intensity value. Confocal microscopy (Nikon C1 confocal microscope) was used for co-bombardment images.

Data Analysis

In each replicate, tube length, width, and intensity were examined. In all cases, at least 50 tubes were used to calculate the average length or tip width in each bombardment (i.e. one replicate). Each experiment was conducted in three occasions, unless indicated, and data were pooled for statistical analysis. For phosphorylation mutant analysis, only transfected tubes with intensity between 0–25 (arbitrary units) were considered, whereas for eGFP, LePRK2-eGFP and mLePRK2-eGFP tubes, all intensities were used. Data were analyzed by using analysis of the variance, and differences between means were compared using a Tukey's test (p < 0.05) or Student's t test (p < 0.05).

Latrunculin B Treatment

Pollen bombarded with eGFP, LePRK2-eGFP, and mLePRK2-eGFP clones was separated in two wells, with 500 μl of pollen germination medium per well and rocked at room temperature at 60 rpm. Three hours after bombardment, latrunculin B (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to final concentration of 5 nm. Dimethyl sulfoxide was used as control experiment. After 4 h of incubation, tubes were observed under the epifluorescence microscope.

RESULTS

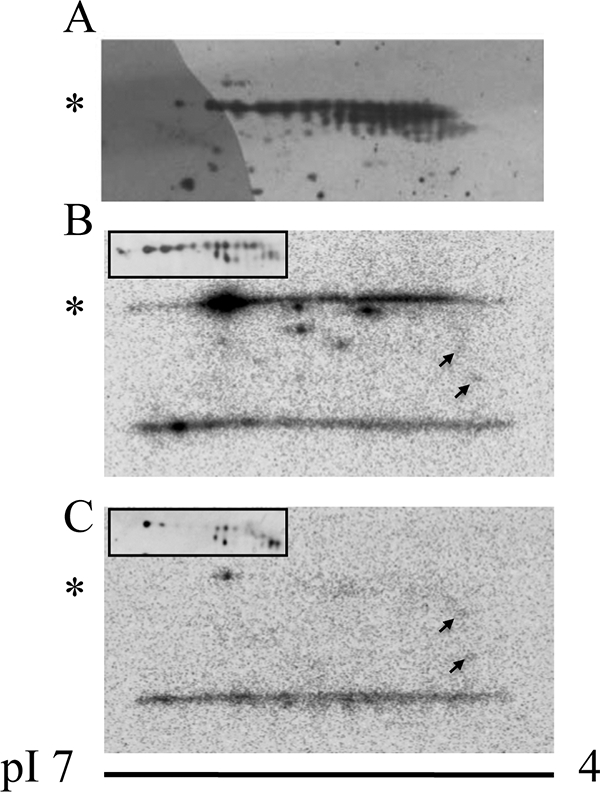

Two-dimensional Gel Analysis Suggests That LePRK2 Is Highly Phosphorylated in Pollen Membranes

We previously showed that LePRK2 in pollen membranes could be phosphorylated in vitro (1, 6). To gain more insight into the in vivo phosphorylation status of LePRK2, tomato mature pollen membrane proteins were resolved by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and used for immunoblots with polyclonal antibodies against the extracellular domain of LePRK2 (6). The high number of spots shown in Fig. 1A suggest the presence of multiple isoforms of LePRK2. Despite the possibility that some of the spots could correspond to other post-translational modifications, the two-dimensional pattern suggests that several phosphorylated isoforms of LePRK2 are present in pollen membranes. To acquire more understanding about LePRK2 phosphorylation in pollen, tomato pollen membranes were incubated with [γ- 32P]ATP in an in vitro kinase assay and then resolved by two-dimensional gels. Fig. 1B showed a number of phosphorylated spots spread mostly in the region corresponding to LePRK2. Then, the labeling reaction was carried out in the presence of Style interactor for LePRKs, a style molecule that specifically dephosphorylates LePRK2 and stimulates pollen tube growth in vitro (1, 12). Fig. 1C showed that the radioactive signal disappeared, suggesting that the most of the signals shown in Fig. 1B corresponded to phosphorylated LePRK2.

FIGURE 1.

Two-dimensional gel analysis suggests that LePRK2 is highly phosphorylated in tomato pollen. The acidic end of the gel (pH 4) is at the right of each panel. Asterisks indicate the position of LePRK2. A, membrane fractions from germinated pollen (200 μg) were separated by two-dimensional gels (pH 4–7) and immunoblotted with anti-LePRK2. B and C, membrane fractions from mature pollen (200 μg) incubated with [γ-32P]ATP without (B) or with (C) pure fractions of Style interactor for LePRKs and then separated by two-dimensional gels (pH 4–7). In B and C, insets show Western blots of the same two-dimensional gels. The arrows showed two spots that did not change after incubation with Style interactor for LePRKs. These results were repeated three times.

Prediction of LePRK2 Phosphorylation Mutants

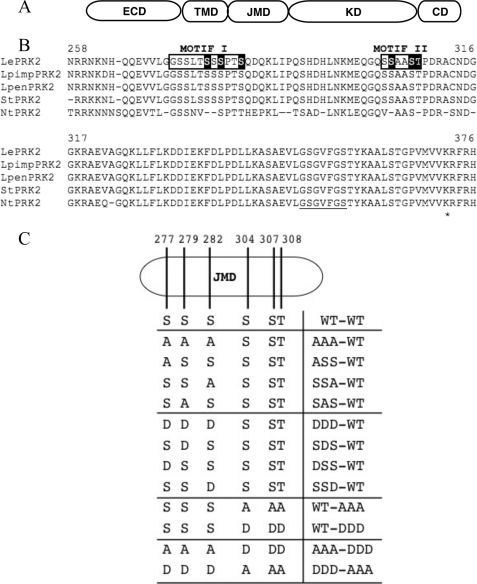

Fig. 1 suggests that LePRK2 is highly phosphorylated in pollen membranes. We decided to evaluate the significance of the putative phosphorylation residues of LePRK2 on pollen tubes phenotype. The JM domain of LePRK2 (Fig. 2A) has a high number of putative phosphorylatable residues (Fig. 2B) as determined by predictive algorithms. It has been suggested that phosphorylation of JM residues is involved in providing specific signaling properties to receptor kinases (26–28). To investigate the effect that modification of potential phosphorylation residues of LePRK2 would have on the tubes phenotype, we decided to introduce mutations in selected residues of the JM domain. To select which residues to mutagenize, two independent computer-assisted approaches that predict phosphorylation sites were used: NetPhos (version 2.0; 22) and GPS (version 2.0; 23). Both algorithms reveal possible phosphosites on phosphorylated proteins. We chose residues that were predicted with high scores by both algorithms (as an example, NetPhos scores are shown in supplemental Table 2). We also based our selection on the comparative analysis of the amino acid sequences of the cytoplasmic domains of LePRK2 and partial sequences of its putative orthologs from other close species such as wild tomatoes (Solanum pimpinellifolium and Solanum pennellii), potato (Solanum tuberosum), and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) (Fig. 2B) (29). We selected six putative phosphorylated residues within the JM domain (Ser277, Ser279, Ser282, Ser304, Ser307, and Thr308), which showed the highest score with both algorithms and that were also conserved among most of the LePRK2 putative orthologs. These six selected residues (underlined in the sequences shown below) are grouped in two distinct motifs, 271GGSSLTSSSPTS (motif I) and 301GQSSAASTP (motif II) (Fig. 2B). All mutant constructs, where the selected residues were either replaced individually or in groups with alanine (a nonphosphorylatable amino acid) or with aspartic acid (a phosphomimicking mutation), were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the pLAT52-LePRK2-eGFP plasmid (7). To simplify analysis, residues Ser277, Ser279, and Ser282, and Ser304, Ser307, and Thr308 were first grouped in two separate constructs, AAA-WT (denoting mutations in motif I, and wt in motif II) and WT-AAA (denoting wt in motif I and mutations in motif II) for the alanine mutants and DDD-WT and WT-DDD for the aspartic mutants, respectively (Fig. 2C). All constructs were transiently expressed in tobacco pollen, and the length of the tubes and the width of the tubes tip were measured.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of selected LePRK2 mutants. A, diagram of LePRK2 protein domains. ECD, extracellular domain; TMD, transmembrane domain; JMD, juxtamembrane domain; KD, kinase domain; CD, C-terminal domain. B, alignment of putative homologues of LePRK2. LePRK2, S. esculentum; LpimpPRK2, S. pimpinellifolium; LpenPRK2, S. pennellii; StPRK2, S. tuberosum; NtPRK2, N. tabacum. Base numbers refer to the LePRK2 sequence. Selected residues are highlighted. Motifs I and II are shown by boxes. Subdomain I of the kinase domain is underlined. An asterisk highlights Lys372, the residue mutated in the mLePRK2 construct. C, cartoon of LePRK2 showing the selected LePRK2 phosphorylation sites. The LePRK2 mutants are arranged in groups. The first eight mutants have mutations at Ser277, Ser279, and Ser282 (AAA-WT, S277A/S279A/S282A; ASS-WT, S277A/S279/S282; SSA-WT, S277/S279/S282A; SAS-WT, S277/S279A/S282; DDD-WT, S277D/S279D/S282D; SDS-WT, S277/S279D/S282; DSS-WT, S277D/S279/S282; and SSD-WT, S277/S279/S282D). The second group contains mutations at Ser304, Ser307, and Thr308 (WT-AAA, S304A/S307A/T308A and WT-DDD, S304D/S307D/T308D), and the third group has two combinations of mutations of the first and second group (AAA-DDD, S277A/S279A/S282A/S304D/S307D/T308D; DDD-AAA, S277D/S279D/S282D/S304A/S307A/T308A).

Triple Alanine Mutant AAA-WT Increased Pollen Tube Length

It was previously shown that pollen tubes that transiently overexpressed LePRK2 showed slightly wider tips (7). The effect of eliminating the three selected potential phosphorylation residues in motif I was analyzed first. Pollen tubes expressing AAA-WT at low levels of fluorescence (i.e. brightness of eGFP) (0–25 arbitrary units) were significantly longer, compared with LePRK2-eGFP (referred as WT-WT tubes) with similar levels of fluorescence (Fig. 3A).

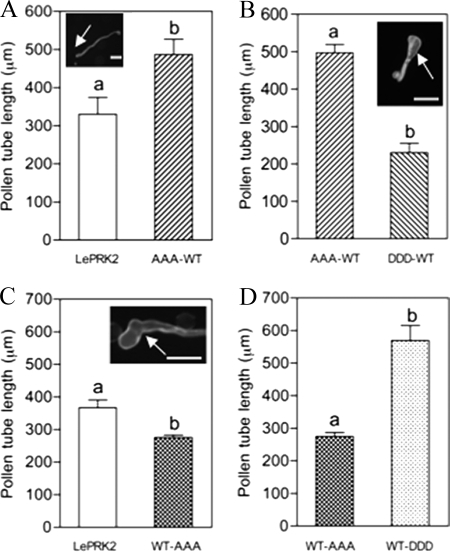

FIGURE 3.

The increase in pollen tube length by the triple mutant AAA-WT is neutralized by the triple mutant DDD-WT. Data are means ± S.E. of three replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences. The arrow indicates the pollen tube tip. Scale bar represents 100 μm. A, AAA-WT tubes are significantly longer than in LePRK2-eGFP tubes (referred as WT-WT in the text) (p < 0.05). Inset shows a representative AAA-WT tube. B, AAA-WT induced phenotype is annulled by expression of DDD-WT (p < 0.05). Inset shows a representative DDD-WT tube. C, WT-AAA tubes are significantly shorter than LePRK2 (referred as WT-WT in the text) (p < 0.01). Inset shows a representative WT-AAA tube. D, WT-AAA inhibition of growth is annulled by WT-DDD (p < 0.05).

Mutant AAA-WT tubes showed phenotypically normal tubes (see inset of Fig. 3A). Even though the tips of WT-WT tubes (see Fig. 6C below) seemed to be wider compared with those of AAA-WT tubes, no significant differences were found. This result suggests that the lack of phosphorylation of these three residues in motif I derepressed the inhibition of tube growth caused by LePRK2-eGFP overexpression, but it was not able to reduce the tip width.

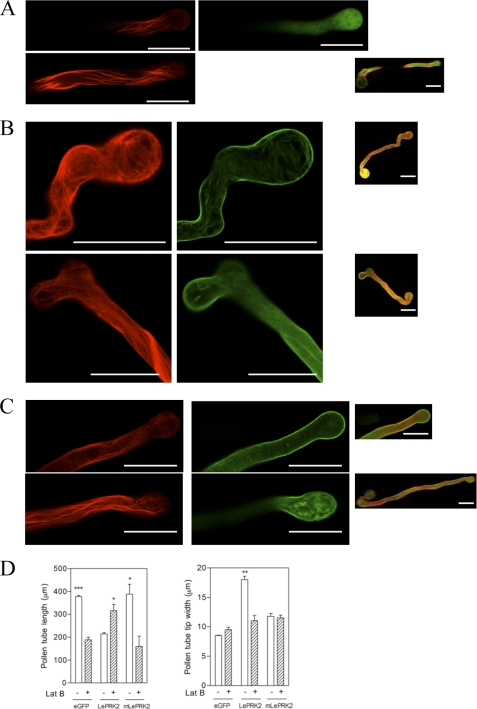

FIGURE 6.

LePRK2 but not mLePRK2 induced a stable actin network at the pollen tube tip. eGFP (A), LePRK2-eGFP (B), or mLePRK2-eGFP (C) were transiently co-expressed with mRFP-mTalin in tobacco pollen and visualized using confocal microscopy (RFP, left panels; eGFP, right panels). Scale bar represents 100 μm. Medial sections of the pollen tube are shown. Far right panels showed projection of the whole pollen tube with merged fluorescent emissions (eGFP+RFP). D, effect of latrunculin B (Lat B) on pollen tube length and tip width of pollen tubes overexpressing eGFP, LePRK2-eGFP, and mLePRK2-eGFP. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001.

Therefore, the ability of the AAA-WT to increase tube length could be explained by an impaired activity due to the mutations. We found that tubes with single mutations ASS-WT, SSA-WT, and SAS-WT, where only one of the three residues was mutated into alanine, showed intermediate lengths compared with the lengths of WT-WT and AAA-WT tubes (Table 1). The tube length of the single mutants was similar irrespective of which of the three residues were mutated, suggesting that LePRK2 activity depends on the number of residues inactivated.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of individual mutants

| Length | |

|---|---|

| μm | |

| WT-WT | 350.9 ± 27.4 |

| AAA-WT | 694.2 ± 71.3 |

| SAS-WT | 544.3 ± 70.8 |

| SSA-WT | 542.2 ± 56.3 |

| ASS-WT | 525.6 ± 66.5 |

| WT-WT | 408.7 ± 64.6 |

| DDD-WT | 483.4 ± 66.7 |

| DSS-WT | 455.7 ± 75.0 |

| SDS-WT | 257.8 ± 95.2 |

| SSD-WT | 384.0 ± 34.2 |

The role of phosphorylated residues can also be studied by creating constitutively active versions that is by replacing the residues with aspartic acids, which simulate a phosphorylated amino acid. The construct DDD-WT, which has three residues of motif I replaced with aspartic acids, completely annulled the AAA-WT phenotype, where DDD-WT tubes were significantly shorter than AAA-WT tubes (Fig. 3B) with swollen tips (see inset of Fig. 3B) similar to WT-WT tips. When any of these three residues were mutated to aspartic acid, the single SDS-WT, DSS-WT, and SSD-WT mutant tubes showed similar lengths to those of DDD-WT (Table 1); this suggests that replacing only one of the three amino acids of motif I to aspartic acid was sufficient to restore lengths equivalent to those of DDD-WT. All of these results suggest that the three residues Ser277/Ser279/Ser282 of motif I in the JM domain of LePRK2 have a role in the regulation of pollen tube growth so that phosphorylation of any individual residue would reduce pollen tube length in tobacco overexpression assays.

Triple Alanine Mutant WT-AAA Decreased Pollen Tube Length

We then analyzed the effect of replacing all three of the selected residues in motif II of the JM domain with alanines. Surprisingly, and contrary to the long tubes seen in the AAA-WT mutant, the WT-AAA tubes were significantly shorter than WT-WT tubes (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, some of the transformed tubes exhibited a loss of growth polarity, turning in their growing direction and resulting in hockey stick-like tubes (see inset of Fig. 3C).

To check whether phosphomimicking residues would revert the phenotype of the WT-AAA mutant, the three residues in motif II were replaced by aspartic acid. As shown in Fig. 3D, the WT-DDD tubes were significantly longer than WT-AAA tubes, and as long as the AAA-WT tubes (Fig. 3A; also see Fig. 4B below), with similar morphology to the eGFP tubes. These results suggest that phosphorylation of residues Ser304/Ser307/Thr308 within motif II has a positive effect on pollen tube length when overexpressed in tobacco pollen compared with LePRK2-GFP.

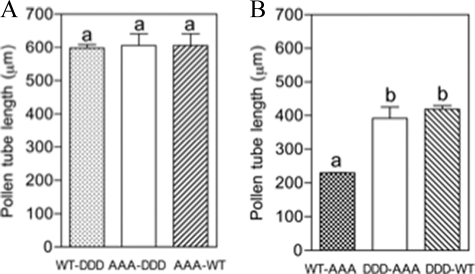

FIGURE 4.

Sextuple mutants showed no additive effects either in elongation (AAA-DDD) or shortening (DDD-AAA) of pollen tubes. Data are means ± S.E. of two replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences. A, AAA-DDD tubes were not significantly different in tube length when compared with WT-DDD or AAA-WT tubes. B, DDD-AAA tubes were not significantly different in tube length compared with DDD-WT tubes but were significantly different to WT-AAA tubes (p < 0.05).

Sextuple Mutants AAA-DDD and DDD-AAA Showed No Additive Effects Either in Elongation or Shortening of Pollen Tubes, Respectively

We demonstrated here that substitution of residues in motif I by alanines (mutant AAA-WT) and substitution of residues in motif II by aspartic acids (mutant WT-DDD) both yielded long pollen tubes. Therefore, to analyze whether these two effects were additive, a construct that included all six mutated residues was created. This sextuple mutant (AAA-DDD), with full replacement of the six residues S277A/S279A/S282A/S304D/S307D/T308D, was expressed in pollen tubes. The AAA-DDD tubes showed no significant differences in pollen tube length relative to the WT-DDD and AAA-WT mutants (Fig. 4A). This result suggests that, under our experimental conditions, the pollen tubes could not increase their length more than that shown by AAA-WT or WT-DDD mutants. It is still possible that mutating some other residues in LePRK2, together, or not, with these residues, would allow longer tubes.

Similarly, the other sextuple mutant (DDD-AAA) that combines the mutants WT-AAA and DDD-WT, both of which caused a significant shortening of the pollen tubes, relative to the lengths of WT-WT or to AAA-WT tubes, respectively, was created. However, DDD-AAA tubes had lengths similar to those of DDD-WT and were significantly longer than WT-AAA tubes (Fig. 4B). This result suggests that phosphorylation of the residues of motif I has a dominant effect on any modification of the residues of motif II.

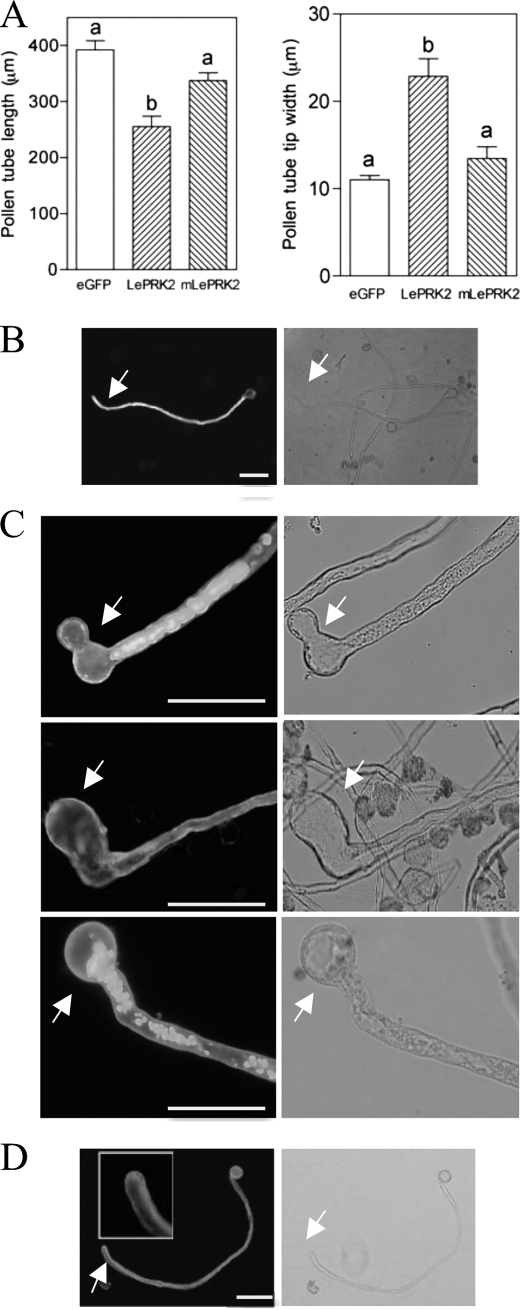

Overexpression of LePRK2 but Not mLePRK2 Reduced Pollen Tube Growth and Induced Tip Swelling

To evaluate whether the kinase activity of LePRK2 is required for the LePRK2 overexpression pollen tube phenotype, we generated fusion constructs containing the complete open reading frame of a mutant version of LePRK2 (mLePRK2), where the K372 residue in the subdomain II of the kinase domain was changed into alanine. We previously showed that the cytoplasmic domain of a mutated LePRK2 in Lys372 had no in vitro kinase activity (6) and that the LePRK2 kinase activity is required for binding to LePRK1 (1). mLePRK2 construct was fused to eGFP under the control of the LAT52 promoter (pLAT52). pLAT52-LePRK2-eGFP and pLAT52-eGFP were used as controls.

As reported, LePRK2-eGFP significantly decreased pollen tube length and increased pollen tube width at the tip relative to the eGFP control (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, mLePRK2 tubes were statistically similar in length and width to eGFP tubes (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the kinase activity of LePRK2 was relevant for these observed phenotypes. Because LePRK2-eGFP tubes were wider at the tip and shorter than eGFP or mLePRK2-eGFP tubes, their width/length ratio (0.089 ± 0.009) was also higher compared with eGFP (0.028 ± 0.007) and to mLePRK2-eGFP tubes (0.039 ± 0.007).

FIGURE 5.

LePRK2 but not mLePRK2 reduced pollen tube growth and induced tip swelling. A, data are means ± S.E. of three replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). B–D, representative eGFP (B), LePRK2-eGFP (C), and mLePRK2-eGFP (D) pollen tubes are shown. Scale bar represents 100 μm. Arrows indicate pollen tube tips. The inset shows the pollen tube tip. Left and right panels, GFP channel and bright field images, respectively. Fig. 5A was also performed at 5 h of germination obtaining similar results. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

Although eGFP control tubes (Fig. 5B) were indistinguishable from nontransformed tubes, LePRK2-eGFP tubes often showed swollen tips (Fig. 5C). Presumably, these tubes elongated well for a period of time before balloons developed, and then growth was arrested. In some cases, after the appearance of balloons, pollen tubes resumed growth after laterally defining a new tip (Fig. 5C, upper panel) or exhibited loss of growth polarity, resulting in hockey stick-like tubes (Fig. 5C, middle panel), seen also upon overexpression of WT-AAA tubes (Fig. 3C), AtRac7 (10), or PiCDPK1/DN (30). Some LePRK2-eGFP tubes but not mLePRK2-eGFP tubes also showed one or more vacuoles that filled most of the volume of the swollen tip (Fig. 5C, top and bottom). Vacuolated tube tips were also found in pollen tubes that overexpressed LeKPP (8) and AtRac7 (10). On the other hand, mLePRK2-eGFP tubes were statistically similar to eGFP control tubes displaying long tubes with thin tips (Fig. 5D). The kinase activity of LePRK2 seems to be essential for sustaining the extreme phenotype of LePRK2 tubes because mLePRK2-eGFP tubes annulled the depolarized growth being statistically similar in length and width tip to eGFP tubes. A similar situation was also seen when the Arabidopsis homolog of LePRK2, AtPRK2a, was overexpressed in tobacco pollen; AtPRK2a tubes were wider than tubes expressing a presumptive kinase-inactive mutant, mAtPRK2a (18).

As it was demonstrated before (6, 29), LePRK2 is localized to the plasma membrane of the tube, predominantly at the tip and at the shank (Fig. 5C) (6, 29). In tubes with strong fluorescence, LePRK2 also localized in some vesicle-like cytoplasmic compartments (Fig. 5C, top and bottom). These compartments were apparently similar to the ones obtained in tubes treated with brefeldin A, a drug that inhibits recycling of internalized proteins to the membrane (10, 31). mLePRK2 showed always plasma membrane localization (see inset of Fig. 5D; Fig. 6C, right panel, see below), suggesting that the contrasting phenotypes were due to the kinase activity of LePRK2 and not to a different localization in pollen tubes.

LePRK2 Overexpression Influences Actin Dynamics

To visualize actin in pollen tubes, we co-expressed the pLAT52-mRFP-mTalin gene together with either pLAT52-LePRK2-eGFP, pLAT52-mLePRK2-eGFP, or pLAT52-eGFP. As expected, eGFP control tubes showed thick and longitudinally oriented actin cables along the shank of the tube with fine filaments close to the tip (Fig. 6A, top and middle panel) (32–34). However, when LePRK2-eGFP was expressed together with mRFP-mTalin, actin cables displayed a different organization; thick actin cables extended into the balloon tip area of LePRK2-eGFP tubes with a disorganized arrangement in the expanded tips (Fig. 6B, left panels). mTalin did not significantly affect growth and morphology of the pollen tubes and localization of LePRK2 was always confined to the tube plasma membrane (Fig. 6B, right panels). On the other hand, mLePRK2-eGFP tubes never showed LePRK2-eGFP phenotypes, displaying actin filaments closer to those in the eGFP control tubes (Fig. 6C, left panels).

To test whether pollen tube depolarization caused by the overexpression of LePRK2 was dependent on actin disturbance, eGFP, LePRK2-eGFP, and mLePRK2-eGFP tubes were separately treated for 4 h with latrunculin B, a drug that at low concentration (5 nm) promotes actin depolymerization blocking pollen tube growth without affecting pollen tube morphology (35). As described previously (33), 5 nm latrunculin B significantly reduced the length of eGFP control tubes without affecting tip width (Fig. 6D). However, 5 nm latrunculin B partially increased pollen tube length in LePRK2-eGFP tubes and suppressed the tip swelling, whereas the mLePRK2-eGFP tubes appeared similar to eGFP control tubes after latrunculin B treatment (Fig. 6D). These results showed that LePRK2 overexpression exerts its effect through actin polymerization because incubation with latrunculin B suppressed depolarized growth, suggesting that in wt pollen tubes LePRK2 acts on tube length through the regulation of actin dynamics.

DISCUSSION

By mutating the putative phosphorylation sites of LePRK2, we have shown a reciprocal role for two motifs located in the JM domain. NetPhos (version 2.0) and GPS (version 2.0) were used as starting tools to orientate our selection of the residues. It is important to mention that additional residues located in the kinase domain of LePRK2 predicted by both algorithms did not show any evident phenotype (data not shown).

All phosphorylation mutants showed pollen tube membrane localization (see Fig. 3), indicating that the differences found could not be attributed to an incorrect localization of any of the mutated LePRK2-eGFP proteins. We showed that blocking phosphorylation of residues in motif I (Ser277/Ser279/Ser280), by substitution with alanines, derepressed the inhibition of tube growth caused by LePRK2-eGFP overexpression. In contrast, replacement with alanines of residues in motif II (Ser304/Ser307/Thr308) exacerbated the inhibitory effect on tube length shown by overexpression of LePRK2-eGFP. It is plausible that in vivo, there would be an equilibrium between these two reciprocal motifs, thus maintaining a fine-tuned regulation of polar tube growth. However, the high number of spots observed in Fig. 1 also suggested that constitutive phosphorylation is likely to occur at multiple sites of LePRK2. The functional significance of this constitutive phosphorylation is unknown.

Clustering of residues in phosphorylation motifs might suggest that their phosphorylation could be sequential, with full activation after phosphates occupied all sites. This does not appear to be the case for LePRK2 because when only one residue of motif I was replaced by aspartic acid (SDS-WT, DSS-WT, or SSD-WT mutants), the tubes showed depolarized growth similar to that seen with the DDD-WT mutant or with WT-WT. One possibility that should be explored is whether phosphorylation of any residues of one motif inhibits phosphorylation of residues of the other motif.

Fig. 4A showed that AAA-DDD tubes did not show significant length increases relative to AAA-WT and WT-DDD tubes, suggesting that, at least under our experimental conditions, the sextuple mutant tubes reached a physiological limit, with no possible further increase in their length. The situation is different when the tip width is analyzed. None of the phosphorylation mutants, even those with weak fluorescence, showed significant differences in tip width relative to LePRK2-eGFP tubes, in contrast to mLePRK2-eGFP tips, which showed normal widths at all fluorescence intensities. These results suggest the mutation K372A was more effective in regulating tip width than the substitution of up to six potentially phosphorylated residues.

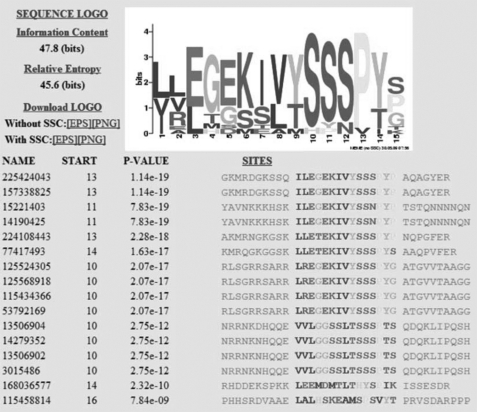

Phosphorylation regulatory motifs have been found in other molecules, such as TGF-β-receptor I (TβRI) (36). A phosphorylatable TβRI motif (GS motif) in the JM domain regulates TGF-β signaling activity (36). Using 200 sequences of receptor like kinases retrieved from BLAST searches with the cytoplasmic domain of LePRK2 as query and using a motif search method (see below), we found among these 200 sequences two statistically significant motifs. One shows identity with the GS motif of TβRI (36), and the other is the motif I of LePRK2 characterized here. The sequence logo as derived from the MEME program for motif I together with the list of the 15 putative homologous LePRK2 proteins retrieved by MEME analysis are shown in the Fig. 7. Moreover, two of the residues of the motif I (Ser277 and Ser279) that showed biological activity (Fig. 3) were highly conserved in the MEME alignment. The situation was different for motif II because it was only conserved in the close LePRK2 relatives as shown in Fig. 2B. This analysis suggests that phosphorylation at motif I might be a general mechanism among all these receptor like kinases, and the one present in motif II is due to functional diversification.

FIGURE 7.

LePRK2 has a phosphorylation regulatory motif. Sequence logo was as derived from the MEME program for motif I and the list of the 15 close putative homologous LePRK2 proteins obtained under the MEME analysis. 3015486 corresponds to LePRK2. Motif I in the LePRK2 molecule is G271GSSLTSSSPTS (residues mutated in the analysis are underlined). Residue 1 of the MEME output corresponds to Leu268 in LePRK2 molecule. The obtained putative homologous proteins are as follows: 225424043 and 157338825 (Vitis vinifera); 15221403 and 14190425 (Arabidopsis thaliana); 224108443 (Populus trichocarpa), 77417493 (Malus domestica) and 12552430 (Oryza sativa var. Indica); 125568918, 115434366, and 53792169 (O. sativa var. Japonica); 13506904 (S. pimpinellifolium), 14279352 (Solanum peruvianum), 13506902 (S. pennellii), 168036577 (Physcomitrella patens), and 115458814 (O. sativa var. Japonica). SSC, small-sample correction.

Overexpression of LePRK2 generates isotropic growth similar to that caused by overexpression of AtRop1 (11), AtRac7 (10), NtRac5 (37), PiCDPK1 (30), or a nearly full-length LeKPP (8). Although mLePRK2 tubes also showed significant differences in the length and width when compared with LePRK2 tubes (Fig. 5A), these differences were smaller than comparing LePRK2 to eGFP tubes (Fig. 5A). This partial effect may be explained by the fact that even though mLePRK2 is not able to phosphorylate itself or other pollen proteins, it was capable of being phosphorylated by endogenous pollen kinases.

The LePRK2-eGFP phenotype was not merely caused by overexpression of a protein because overexpression of mLePRK2-eGFP tubes had tube lengths and tip widths significantly similar to eGFP tubes. These results also support the hypothesis that the kinase activity of LePRK2 is responsible for the observed changes in LePRK2-eGFP tubes.

We also propose that LePRK2 is associated with the regulation of the actin filaments during tube elongation because LePRK2 overexpressing tubes showed an abnormal deposition of actin filaments. Second, latrunculin B specifically relieved the short tubes with swollen tips phenotype of LePRK2-eGFP tubes. Even though a direct relationship has not been validated, the function of LePRK2 could involve the regulation of F-actin distribution through pollen Rho of plants GTPases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sheila McCormick, Weihua Tang, and Yan Zhang for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Sara Maldonado for stimulating discussion. We thank Sheila McCormick and Weihua Tang for providing the pLAT52-LePRK2-eGFP and LAT52-mRFP-mTalin plasmids. We thank Pablo do Campo for help with confocal microscopy.

This work was supported by Grants Universidad de Buenos Aires UBACYT-X109, Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica PICT2005-31656, PICT2007-01976, and Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas PIP-CONICET-5545 (to J. M.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

- JM

- juxtamembrane

- mLePRK

- mutant version of LePRK2

- pLAT52

- pollen-specific LAT52 promoter

- KPP

- kinase protein partner

- MEME

- multiple EM for motif elicitation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wengier D., Valsecchi I., Cabanas M. L., Tang W. H., McCormick S., Muschietti J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6860–6865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheung A. Y., Wu H. M. (2008) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 547–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cai G., Cresti M. (2009) J. Exp. Bot. 60, 495–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cárdenas L., Lovy-Wheeler A., Kunkel J. G., Hepler P. K. (2008) Plant Physiol. 146, 1611–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hématy K., Höfte H. (2008) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 321–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muschietti J., Eyal Y., McCormick S. (1998) Plant Cell 10, 319–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang D., Wengier D., Shuai B., Gui C. P., Muschietti J., McCormick S., Tang W. H. (2008) Plant Physiol. 148, 1368–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaothien P., Ok S. H., Shuai B., Wengier D., Cotter R., Kelley D., Kiriakopolos S., Muschietti J., McCormick S. (2005) Plant J. 42, 492–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shichrur K., Yalovsky S. (2006) Trends Plant Sci. 11, 57–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheung A. Y., Chen C. Y., Tao L. Z., Andreyeva T., Twell D., Wu H. M. (2003) J. Exp. Bot. 54, 73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li H., Lin Y., Heath R. M., Zhu M. X., Yang Z. (1999) Plant Cell 11, 1731–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wengier D. L., Mazzella M. A., Salem T. M., McCormick S., Muschietti J. P. (2010) BMC Plant Biol. 10, 33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu W. H., Wang Y. S., Liu G. Z., Chen X., Tinjuangjun P., Pi L. Y., Song W. Y. (2006) Plant J 45, 740–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miyahara A., Hirani T. A., Oakes M., Kereszt A., Kobe B., Djordjevic M. A., Gresshoff P. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25381–25391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oh M. H., Wang X., Kota U., Goshe M. B., Clouse S. D., Huber S. C. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 658–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang X., Goshe M. B., Soderblom E. J., Phinney B. S., Kuchar J. A., Li J., Asami T., Yoshida S., Huber S. C., Clouse S. D. (2005) Plant Cell 17, 1685–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yun H. S., Bae Y. H., Lee Y. J., Chang S. C., Kim S. K., Li J., Nam K. H. (2009) Mol. Cells 27, 183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Y., McCormick S. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18830–18835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abramoff M., Magelhaes P., Ram S. (2004) Biophotonics Int. 11, 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jeanmougin F., Thompson J. D., Gouy M., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 403–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bailey T. L., Elkan C. (1994) Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 2, 28–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blom N., Gammeltoft S., Brunak S. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 294, 1351–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xue Y., Zhou F., Zhu M., Ahmed K., Chen G., Yao X. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W184–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dowd P. E., Coursol S., Skirpan A. L., Kao T. H., Gilroy S. (2006) Plant Cell 18, 1438–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hwang J. U., Gu Y., Lee Y. J., Yang Z. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5385–5399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hubbard S. R. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 464–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pawson T. (2004) Cell 116, 191–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nühse T. S., Stensballe A., Jensen O. N., Peck S. C. (2004) Plant Cell 16, 2394–2405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim H. U., Cotter R., Johnson S., Senda M., Dodds P., Kulikauska R., Tang W., Ezcura I., Herzmark P., McCormick S. (2002) Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yoon G. M., Dowd P. E., Gilroy S., McCubbin A. G. (2006) Plant Cell 18, 867–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang Q., Kong L., Hao H., Wang X., Lin J., Samaj J., Baluska F. (2005) Plant Physiol. 139, 1692–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen C. Y., Cheung A. Y., Wu H. M. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 237–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fu Y., Wu G., Yang Z. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152, 1019–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kost B., Spielhofer P., Chua N. H. (1998) Plant J. 16, 393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gibbon B. C., Kovar D. R., Staiger C. J. (1999) Plant Cell 11, 2349–2363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wieser R., Wrana J. L., Massagué J. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 2199–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klahre U., Becker C., Schmitt A. C., Kost B. (2006) Plant J. 46, 1018–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.